Abstract

‘Régulation’ theory analyses the long-term transformation in capitalist economies and their consequences for growth patterns and cyclical adjustments. The degree of coherence of a specific configuration of the major institutional forms – monetary regime, wage-labour relation, form of competition, state–citizen institutionalized compromise and mode of support of the international regime – defines various accumulation regimes and ‘régulation’ modes. Over one century, several regimes have been observed along with a succession of changing patterns for the related structural crises. The demise of the post-Second World War Fordist regime has been associated with an uncertain process of institutional restructuring and the coexistence of various brands of capitalism.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Adjustment

- Accumulation regimes

- Capitalism

- Coevolution

- Complementarity

- Credit

- Diffusion of technology

- Fine tuning

- Fordism

- Hierarchy

- Historicism

- Information technology

- Institutionalism

- Isomorphism

- Kalecki, M.

- Keynesianism

- Marxism

- Mass production

- régulation

- Stabilization policies

- Stagflation

- Welfare state

JEL Classifications

Since the 1980s, the term ‘régulation’ has suggested state intervention in the name of economic management though its opposite, ‘dérégulation’, has been more widely used. In the area of economic policy and in accordance with Keynesian precepts, regulation indicates the adjustment of macroeconomic activity by means of budgetary or monetary contra-cyclical interventions. In the area of public management, a complete body of literature, under the name of regulation theory, has investigated the methods for organizing the decentralization of the supply of various public utilities.

This term is also used in physics and biology. In mechanics, a regulator is a means to stabilize the rotary speed of a machine. In biology, regulation corresponds to the reproduction of substances such as DNA. In general terms, the theory of systems involves the study of the role of a set of negative and positive feedback loops in relation to the stability of a complex network of interactions.

Here, a third and different, but not totally unrelated, meaning of the term will be developed. Theories of régulation constitute an area of research which has focused on analysing long-term transformations in capitalist economies. Initially, it focused on American and French capitalisms (Aglietta 1982; Benassy et al. 1979) but it was progressively extended first to major OECD economies (Mazier et al. 1999) then to Latin American countries (Hausmann 1981; Ominami 1985) and ultimately Asian countries (Bertoldi 1989; Boyer 1994). A general presentation of the present state of the theory is to be found in Boyer and Saillard (2002) and a large sample of national case studies in Jessop (2001). Basically, the theory of régulation combines Marxian intuitions and Kaleckian macroeconomics with institutionalist and historicist studies, mobilizing most of the tools of modern economic analysis.

At a primary level, a form of régulation denotes any dynamic process of adaptation of production and social demand resulting from a conjunction of economic adjustments linked to a given configuration of social relations, forms of organization and productive structures (Boyer 1990).

Most economic theories emphasize the general invariables of eminently abstract systems, in which history serves merely as a confirmation or, failing that, as a perturbation. Neoclassical theory studies the shift of a stable equilibrium after an external shock, Keynesian economists stress the role of effective demand and fine tuning whatever the context and the period. Even Marxists tend to extrapolate, as general laws, the quite specific evolutions observed in the early phases of capitalism. In contrast, the régulation approach seeks a broader interaction between history and theory, social structures, institutions and economic regularities (de Vroey 1984).

The starting point is the hypothesis that accumulation has a central role and is the driving force of capitalist societies. This necessitates a clarification of factors that reduce or delay the conflicts and disequilibria inherent in the formation of capital, and which allow for an understanding of the possibility of periods of sustained growth (Boyer and Mistral 1978). These factors are associated with particular regimes of accumulation, namely, the form of articulation between the dynamics of the productive system and social demand, the distribution of income between wages and profits on the one hand, and on the other hand the division between consumption and investment. It is then useful to explain the organizational principles which allow for mediation between such contradictions as the extension of productive capacity under the stimulus of competition on product markets, for labour and finance. The notion of institutional form – defined as a set of fundamental social relations (Aglietta 1982) – enables the transition between constraints associated with an accumulation regime and collective strategies; between economic dynamics and individual behaviour. A small number of key institutional forms, which are the result of past social struggles and the imperatives of the material reproduction of society, frame and channel a multitude of partial strategies which are decentralized and limited in terms of their temporal horizon. Five main institutional forms do shape accumulation regimes.

The forms of competition describe by what mechanisms the compatibility of a set of decentralized decisions by firms and individuals is ensured. They are competitive while the ex post adjustment of prices and quantities ensures a balance; they are monopolist if the ex ante socialization of revenue is such that production and social demand evolve together (Lipietz 1979). The type of monetary constraint explains the interrelations between credit and money creation: credit is narrowly limited in terms of movement of reserves when money is predominantly metallic; the causality is reversed when on the contrary the dynamics of credit conditions the money supply in systems where the external parity represents the only constraint weighing upon the national monetary system (Benassy et al. 1979). The nature of institutionalized compromises defines different configurations of relations between the state and the economy (André and Delorme 1983; Jessop 1990): the state-as-referee when only general conditions of commercial exchange are guaranteed; as the interfering state when a network of régulation and budgetary interventions codifies the rights of different social groups. Modes of support for the international regime are also derived from a set of rules which organize relations between the nation state and the rest of the world in terms of commodity exchange, migration, capital movements and monetary settlements. History goes beyond the traditional contrast between an open and a closed economy, free trade and protectionism; it makes apparent a variety of configurations (Mistral 1986; Lipietz 1986a). Finally, forms of wage relations indicate different historical configurations of the relationship between capital and labour, that is, the organization of the means of production, the nature of the social division of labour and work techniques, type of employment and the system of determination of wages, and finally, workers’ way of life including the welfare state. If, in the first stages of industrialization, wage-earners are defined first of all as producers, during the second stage they are simultaneously producers and consumers.

At this point appears the notion of régulation, as a conjunction of mechanisms and principles of adjustment associated with a configuration of wage relations, competition, state interventions and hierarchization of the international economy. Finally, a distinction between ‘small’ and ‘big’ crises is called for (Boyer 1990). The former, which are of a rather cyclical nature, are the very expression of régulation in reaction to the recurrent imbalances of accumulation. The latter are of a structural nature: the very process of accumulation throws into doubt the stability of institutional forms and the régulation which sustains it because the profit does not recover by contrast with conventional business cycles.

Thus, in long-term dynamics as well as in short-term development, institutions are important. Historical research confirms that sometimes institutional forms make an impression on the system in operation; at other times they register major changes in direction. At the end of a period which can be counted in decades, the very mode of development – that is, the conjunction of the mode of régulation and the accumulation regime – is affected: there will be changes in the tendencies of longterm growth and eventually in inflation, specificities of cyclical processes (Mazier et al. 1999).

So a periodization of advanced capitalist economies emerges which is not part of the traditional Marxist theory. Despite the rise in monopoly, the interwar period is still marked by competitive regulation. After the Second World War an accumulation regime without precedent is instituted – that of intensive accumulation centered on mass consumption (Bertrand 1983) – known as Fordist and channelled through monopolist-type regulation.

In fact, the alteration in wage relations – in particular the transition to Fordism, that is, the synchronization of mass production and wage-earners’ access to the ‘American way of life’ – and in monetary management, that is, transition to internally accepted credit money – seems to have played a greater role than the change in modes of competition or conjunctural fine tuning à la Keynes (Aglietta 1982; Aglietta and Orlean 1982; Boyer 1988).

Since the 1960s, many economies have been experiencing a big crisis without historical precedent: stagflation, absence of cumulative depression, breaking-down of most previous economic regularities, length of the period of technological and institutional restructuring (Boyer and Mistral 1978; Lipietz 1985). In consequence, it is logical that former economic policies lose their efficacy (Boyer 1990). First, because the crisis is not cyclical but structural; this invalidates the policy of finetuning; second, because the structural changes which permitted the 1929 crisis to be overcome have become blocked and cannot be repeated (Lipietz 1986b).

Since the formative years, the research programme has been developing both extensively and intensively. The collapse of the Soviet bloc economies has pointed to the need to investigate the necessary and sufficient institutions required for a viable capitalist economy (Emergo 1995; Hollingsworth and Boyer 1997): economic viability depends on the compatibility of a complete set of institutional forms. In the epoch of financialization (Aglietta 1998), information and communication technologies diffusion (Boyer 2004), rise of services (Petit, 1986) and strengthening of foreign competition (Lipietz 1986a), no clear follower to Fordism has yet emerged and diffused. Nevertheless, since the mid-1970s a series of trials and errors concerning the reform of the monetary regime, the tax and welfare system, competition and wage relations has finally delineated a new institutional architecture, quite complex to analyse. Conversion, layering and recomposition of existing institutional forms have replaced the strong synchronization associated with major crises and world wars (Boyer 2005b).

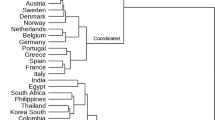

The large number of international comparisons has systematically exhibited the persisting diversity of various brands of capitalism. Within industrialized countries: market dominated, corporate-led, state governed and social democratic versions, with some possible sub-variants, coexist (Amable 2004). An equivalent but different variety is observed for Latin American countries (Quémia 2001). Consequently, the financial crises experienced by Mexico, Brazil and Argentina are quite different, even if they all point out the destabilizing role of global finance upon contrasted domestic accumulation regimes (Boyer and Neffa 2004).

These numerous structural changes call for new directions for the research agenda of régulation theory. Can the concepts of complementarity, hierarchy, isomorphism and coevolution explain how various mixes of institutions can cohere and define a coherent accumulation regime (Boyer 2005a; Socio-Economic Review 2005)? What kind of political economy analysis can explain the emergence and restructuring of institutional forms, especially the choice of monetary regime, the configuration of the welfare state or the nature of insertion into the world economy (Palombarini 1999)? How to analyse multilevel régulation modes, especially in order to understand the complex process of European integration (Boyer and Dehove 2001)? Finally, is not the anthropogenetic model, based on the production of humankind by education, health care and culture, a possible follower of the Fordist regime (Boyer 2004)?

Bibliography

Aglietta, M. 1982. Regulation and crisis of capitalism. New York: Monthly Review Press.

Aglietta, M. 1998. Le capitalisme de demain. Note de la fondation Saint-Simon (101), November.

Aglietta, M., and A. Orlean. 1982. La violence de la monnaie. Paris: PUF.

Amable, B. 2004. The diversity of modern capitalisms. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

André, Ch., and R. Delorme. 1983. L’état et l’économie. Paris: Seuil.

Benassy, J.P., R. Boyer, and R.M. Gelpi. 1979. Régulation des économies capitalistes et inflation. Revue économique 30 (3): 397–441.

Bertoldi, M. 1989. The growth of Taiwanese economy 1949–1989: Success and open problems of a model of growth. Review of Currency Law and International Economics 39: 245–288.

Bertrand, H. 1983. Accumulation, régulation, crise: un modèle sectionnel théorique et appliqué. Revue économique 34: 305–343.

Boyer, R. 1979. Wage formation in historical perspective: The French experience. Cambridge Journal of Economics 3: 99–118.

Boyer, R. 1988. Technical change and the theory of ‘regulation’. In Technical change and economic theory: The global process of development, ed. G. Dosi et al. London: Pinter Publishers.

Boyer, R. 1990. The regulation school. New York: Columbia University Press.

Boyer, R. 1994. Do labour institutions matter for economic development? In Workers, institutions and economic growth in Asia, ed. G. Rodgers. Geneva: ILO/ ILLS.

Boyer, R. 2004. The future of economic growth. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Boyer, R. 2005a. Coherence, diversity and the evolution of capitalisms. Evolutionary and Institutional Economic Review 2 (1): 43–80.

Boyer, R. 2005b. How and why capitalisms differ. Economy and Society 34: 509–557.

Boyer, R., and M. Dehove. 2001. Théories de l’intégration européenne. La Lettre de la Régulation 38: 1–3.

Boyer, R., and J. Mistral. 1978. Accumulation, inflation, crises. Paris: PUF.

Boyer, R., and J. Neffa, eds. 2004. La crisis Argentina (1976–2001). Madrid/Buenos Aires: Editorial Mino y Davila.

Boyer, R., and Y. Saillard, eds. 2002. Regulation theory: The state of the art. London: Routledge.

de Vroey, M. 1984. A regulation approach interpretation of the contemporary crisis. Capital and Class 23 (Summer): 45–66.

Emergo: Journal of Transforming Economies and Societies. 1995. Special issue, 2(4).

Hausmann, R. 1981. State landed property, oil rent and accumulation in Venezuela, Ph.D. thesis, Cornell University.

Hollingsworth, R.J., and R. Boyer, eds. 1997. Contemporary capitalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jessop, B. 1990. State theory. Putting capitalist states in their places. Oxford: Polity Press.

Jessop, B., ed. 2001. Regulation theory and the crisis of capitalism, 5 vols. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Lipietz, A. 1979. Crise et inflation, pourquoi? Paris: Maspéro.

Lipietz, A. 1985. The magic world: From value to inflation. London: Verso.

Lipietz, A. 1986a. New tendencies in the international division of labor. In Production, work, territory, ed. A.J. Scott and M. Storper. London: Allen & Unwin.

Lipietz, A. 1986b. Behind the crisis: The exhaustion of a regime of accumulation. Review of Radical Political Economics 18 (1–2): 13–32.

Mazier, J., M. Basle, and J.F. Vidal. 1999. When economic crises endure. London: M.E. Sharpe.

Mistral, J. 1986. Régime international et trajectoires nationales. In Capitalisme fin de siècle, ed. R. Boyer. Paris: PUF.

More information on régulation theory is available from the Association Recherche et Régulation. Online. Available at http://web.upmf-grenoble.fr/regulation. Accessed 19 Oct 2006.

Ominami, C. 1985. Les transformations dans la crise des rapports nord–sud. Paris: La Découverte.

Palombarini, S. 1999. Vers une théorie régulationniste de la politique économique. L’Année de la Régulation 1999. Vol. 3. Paris: La Découverte.

Petit, P. 1986. Slow growth and the service economy. London: Frances Pinter.

Quémia, M. 2001. Théorie de la régulation et développement: trajectoires latino-américaines. L’Année de la régulation. Vol. 5. Paris: Presses de Sciences-Po.

Socio-Economic Review. 2005. A dialogue on institutional complementarity. 2 (1): 43–80.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Copyright information

© 2018 Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry

Boyer, R. (2018). Regulation. In: The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_1495

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_1495

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-349-95188-8

Online ISBN: 978-1-349-95189-5

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceReference Module Humanities and Social SciencesReference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences