Abstract

Higher education students are being encouraged to spend time studying in another country because of its reputed benefits. Claims are made about the positive impact of study abroad in developing global citizens, yet the current practice gives rise to several paradoxes. These include: how attempts at cultural adaptation can undermine acceptance of cultural pluralism; how an emphasis on risk management can limit students’ learning potential; and how efforts to increase participation in study abroad may perpetuate global inequities. Some possible strategies are offered to avoid these pitfalls and create strong programs that align with the ideals of global citizenship.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

At first glance, a study abroad experience would seem an ideal pathway on the journey to becoming a global citizen. What better way to develop intercultural competence and a global mindset than to fully immerse oneself as a student in another country, with all the associated demands of having to live, work and play amidst cultural, educational and social systems that are different from one’s own? For some students, study abroad can indeed be a ‘life-changing’ experience, a transformative journey that triggers a period of self-reflection and analysis thereby fomenting the development of skills and understanding necessary for global citizenship. For others, study abroad is far from transformational and can, at worst, lead to a reaffirmation of the superiority of one’s own cultural viewpoints. In this chapter, we will examine some paradoxes of the study abroad experience and suggest some possible strategies for enhancing the likelihood of a pathway to global citizenship. In so doing, we acknowledge that the concept of global citizenship is complex and contested. To provide context for this chapter, we offer Byers ’ (2005, 9) definition:

Global citizenship empowers individual human beings to participate in decisions concerning their lives, including the political, economic, social, cultural and environmental conditions in which they live. It includes the right to vote, to express opinions and associate with others, and to enjoy a decent and dignified quality of life. It is expressed through engagement in the various communities of which the individual is a part, at the local , national and global level. And it includes the right to challenge authority and existing power structures – to think, argue and act – with the intent of changing the world.

The term “study abroad ” is generally understood around the world but is subject to a range of meanings and interpretations. For the purpose of this chapter, we are adopting the Canadian Bureau for International Education’s definition:

Study Abroad: An umbrella term referring to any for-credit learning activity abroad including full degree, exchange and Letter of Permission programs as well as experiential or service learning abroad for credit (CBIE 2016).

Included in this definition would be internships, practicums, field schools and study tours of any length, as long as they are for credit, but not volunteer or work placements or independent travel experiences. Even within this definition the range of possible experiences is vast, in terms of factors such as duration, degree of challenge and potential outcomes, adding to the complexity of determining the relationship between study abroad and global citizenship. Discussion of these, and other, factors will form the basis of this chapter, with a principal focus on study abroad in higher education .

Implicit in this definition is the idea that students will study abroad for a relatively short time and transfer the credits gained back to their home institution, from where they will graduate; it does not refer to the increasing number of students worldwide who decide to leave their home country and pursue their education elsewhere. The former is principally a global North phenomenon, while the latter is largely a movement from the global South —an issue to which we will refer later in the chapter.

Journey Outwards, Journey Inwards

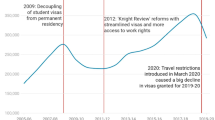

Support for the value of study abroad is growing among leaders in education, government, business, and commerce, not only for the perceived development of global citizens but, more practically, for the enhancement of a wide range of desired employability skills . In many countries, the message is being heard. A recent report (Gribble and Tran 2016 ) commissioned by Universities Australia claims that 16.5% of the 2015 graduating domestic undergraduate cohort have studied abroad, up from 12.3% in 2011. Among some European nations, study abroad rates are even higher, fueled by ERASMUS —the world’s largest student mobility program, launched in 1987—and facilitated by the introduction of the Bologna Declaration in 1999. In Germany , 29% of all undergraduate students and 41% of all masters students had participated in a study abroad experience on completion of their degrees in 2013 and the government has set a target of 50% participation among university students by 2020 (Gribble and Tran 2016 ) . In Canada where, by comparison, the number of study abroad participants remains low at about 3.1% of university students per year, the Canadian Bureau for International Education is garnering support from government and the private sector to implement the recommendation of the government’s International Education Advisory Panel to provide 50,000 study abroad awards annually (McBride 2016).

Beyond the rhetoric and the numbers, questions abound regarding the true value of a study abroad experience, especially in terms of its relationship to global citizenship. In addition to the issues addressed in this chapter, other pertinent questions include:

-

How does a student’s motivation to study abroad, embedded in a complex web of personal, family and socioeconomic factors, impact their learning from the experience?

-

What is the impact of study abroad marketing, often couched in terms of exotic adventures and ‘doing good’ in the world, on participants’ attitudes, perceptions and eventual learning (Zemach-Bersin 2009)?

-

What kind of preparatory learning is required to equip students with the ability to transform a fleeting emotional response to cultural difference into a more refined and reflective platform for intercultural understanding?

-

What should be the key components of a study abroad experience in order to engage students’ critical thinking skills and nurture a commitment towards responsible social action?

-

How, in short, can we best ensure that the journey outwards, to a new nation, culture and landscape, becomes also a journey inwards, to a deeper understanding of self and one’s relationship to the wider world (Pike and Selby 1988)?

Perhaps an even more critical question is whether study abroad is defensible, from a global citizenship perspective, if it is available only to an elite, and privileged, minority (Picard et al. 2009; Green et al. 2015 ) . While governments and international education advocacy organizations continue to promote study abroad , many higher education institutions are turning their attention and resources to ‘internationalization at home’ on the grounds that the majority of students—even in the most optimistic study abroad growth scenarios—will probably not be able to enjoy a study abroad experience. Is study abroad a twenty-first century manifestation of the seventeenth century Grand Tour, undertaken by aristocratic Europeans to further their liberal education and reaffirm their position in society? We shall return to the issue of privilege later in the chapter.

Sense of Belonging

Global citizenship education is an ontological activity (Lilley et al. 2015), and study abroad experiences are unique in their potential as opportunities for students to define who they will become. Whether or not a student resists or embraces global citizenship will depend on their development readiness (Jones 2008). During their sojourn, students may begin to question their identity and discover that they are unprepared to shift their social identification from their in-group (nationality, or home culture) to an outgroup (host culture or global community). At a memorable study abroad debrief one of our students responded to the question “What did you learn?” by replying: “I learned I do not belong here and I really only belong at home.” (personal communication, May 17, 2001) Her statement demonstrates that rather than finding their place in the world, students can return from study abroad with a stronger sense of identification with their home culture (Savicki 2012).

The word ‘belong’ describes the affinity a person has for a specified location or environment. It implies a relationship with a place or, in the context of a study abroad experience, a cultural identity. Paradoxically, the challenge of fitting in with cultures different from those we were raised in can strengthen a sense of belonging to one’s own culture(s) (Osland 2000). Through immersion in another culture, study abroad requires students to relate themselves to a group or a nation to which they do not belong (Allport 1954). This experience of marginality is a critical foundation for intercultural empathy. It is also necessary to develop the ability to construct an identity for oneself that is flexible enough to accommodate a pluralistic existence, a hallmark of a global citizen (Bennett 2012; Lilley 2014). However, if students do not understand their own cultural identity as part of the fabric of a global community prior to their study abroad experience, the challenge to become a member of what was previously an outgroup can confuse their development of self-identity. Rather than embrace their newly expanded vision of the world, students may conclude they do not belong and reject engagement beyond the cultural borders of “home.”

A student’s sense of marginality, more often described as culture shock or cultural transition, is constructive in the sense that the student is actually experiencing the dissonance created by exposure to other ways of existing in the world. As students move through their experience abroad and reach out to develop relationships with cultural others, those relationships can act as a mirror, reflecting back an image of oneself in addition to an image of how one is seen by others (Killick 2012). This reflection can also reveal cultural differences previously unseen or deemed insignificant. However, if students are unable to grasp more than a shallow understanding of cultural differences, the cultural commonalities that allow students to see themselves in the other may be obscured. Overwhelmed by their perception of the threat that differences pose to their identity , the cultural immersion of a study abroad experience can lead students to develop a more polarized view of the world (Hammer et al. 2003).

A study abroad experience allows for the development of a more ethnorelative (Bennett 2012) mindset which can lead students to struggle to find an authentic cultural home in a global community (Coryell et al. 2014 ) . Students who have previously had a monocultural socialization and then experience alternative ways of knowing and being (Hammer et al. 2003) through study abroad may develop a more sophisticated view of the world that brings about the need to make choices, potentially changing their cultural identity . In the ongoing process of becoming, students have to decide which values, ideas and behaviors of their home culture need to be challenged and which elements of their host culture they would be well served to adopt (Osland 2000).

Those who identify strongly with a nation may wonder how they can maintain their allegiance to their national community (Davies and Pike 2009) in light of an expanded view of the world and a newly formed relationship with another or multiple nations. To acknowledge that other ways of knowing and being in the world have validity can threaten a sense of nationalism . Students coming to a study abroad experience steeped in messaging about the superiority of their own culture may not be motivated to give up their allegiance to a nation that they believe to be the best. For study abroad to be a transformative experience, students must first be motivated to move beyond their comfort zones and step outside established communities in order to experience disequilibrium and develop synergy with their new environment (Kolb 2015). For study abroad to provide global citizenship education, students’ efforts to cultivate relationships with a global community need to be both supported and legitimized (Killick 2012).

Managing Risk, Controlling Learning

In a world in which threats to personal safety and security have become increasingly unpredictable, it is not surprising that educational institutions are devoting more attention to risk management and mitigation in their study abroad programs. While the concern for personal well-being is of paramount importance, the impact of risk management strategies on students’ learning needs to be explored if the potential of study abroad for global citizenship education is to be fully understood. Learning theories, within and beyond the student mobility literature, suggest that more profound personal learning happens when the learner is in intellectually or emotionally challenging situations, where she finds herself outside her comfort zone (Killick 2012; Lilley et al. 2015). Study abroad has significant potential for giving rise to a vast array of challenging situations, from the mild to the severe, simply due to the fact that participants are living and working daily outside their comfort zone. To some extent, the degree of challenge will be mitigated by participants themselves, depending on their preparedness to take personal risks in the choices they make in any situation: the student who ventures off alone to explore an unknown city neighborhood will expose herself to potentially greater challenges than her peers who stick together as a group in the city center. However, the degree of challenge will also be established through key decisions made by administrators and organizers in the home institution, including such factors as the location and duration of the study abroad experience as well as the level of preparedness of participants, the degree to which they are supervised and the sophistication of emergency plans.

Study abroad research reports consistently show that students from OECD countries have a strong preference for study abroad destinations in similarly developed countries (Macready and Tucker 2011 ) . There are many reasons for such choices, including the similarity of academic programs and ease of credit transfer, fewer communication challenges (especially the likelihood of one’s own language or English being understood), familiarity with the logistics and services available in the country (e.g., travel systems, standards of accommodation , leisure opportunities), and perceived levels of safety and security. Such choices generally limit the degree of emotional and intellectual dislocation that participants are likely to experience. The field school or field study experience, in which groups of students are led on study tours by their professors, add further layers of comfort through creating a group of like-minded traveling companions to whom one can retreat when the sense of dislocation becomes too severe. Duration is another key factor: despite research to indicate that short-term experiences can be as effective in achieving certain goals, such as intercultural development and personal growth, as semester- or year-long study abroad experiences (Chieffo and Griffiths 2009), the full impacts of culture shock are more likely to be felt during a longer period abroad when the comforting thought of returning home remains in the distant future.

If deep learning requires a feeling of disequilibrium (Killick 2012), the paradox would seem to be that a stronger focus on personal safety, security, and support will limit the personal insights to be gained from addressing the mental destabilization that helps us to reshape our understanding of the world. As Barnett (2004) suggests, as we encounter more descriptions of the world, often in conflict with the stereotypes we hold, we become less certain about our prior interpretations and begin to see our vision of the world as fragile and always contestable. Such uncertainty is a precursor to the intellectual adjustment that needs to take place in the emotional transition from national to global citizenship, the shifting of allegiance and identity from a single country focus to a framework that views that country and all its values in a broader context.

It is generally accepted that the purpose of higher education is to promote deeper learning, including analytical and critical thinking. Students are encouraged to experiment with ideas, to take risks and develop more sophisticated insights into self and society. Study abroad would certainly be considered by most to contribute to that purpose. However, the increasing focus on risk management, alongside the growing trend in higher education toward the development of measurable learning outcomes (Barnett 2004), would seem to limit the learning potential of study abroad experiences. Profound learning often comes from the unplanned encounter, the multisensory onslaught for which no pre-departure briefing can adequately prepare. Such encounters cannot be predicted, but their likelihood can be enhanced or diminished through the decisions taken in planning and implementing the study abroad experience. Of course personal safety has to be a primary consideration and sound planning and preparation are vital in order to mitigate the risks; however, the study abroad experience that incorporates higher levels of personal comfort and security, perhaps in order to attract greater participation , is less likely to achieve the depth of learning, or the sense of social responsibility, that the global citizen requires.

This paradox generates some awkward decisions for study abroad administrators. While it would be irresponsible for any educational institution to condone a study abroad program that knowingly places participants at risk of personal harm, a primary focus on risk management can severely limit participants’ learning potential. Gorski (2008) argues that few administrators are likely to make choices that will leave themselves and their institutions vulnerable but, in choosing the more secure options, they fail in their duty as intercultural educators to challenge existing norms and dominant power structures. The fact that study abroad mobility patterns show a majority of students moving from North to North (Macready and Tucker 2011) is disappointing; the likely impact of an increased focus on risk management reinforcing this trend is troubling for the development of future global citizens.

Reproducing Privilege

In societies where the dominant educational paradigm is to graduate students to compete in the global marketplace and where travel is seen as a leisure activity or as an opportunity to enhance their employability profile, study abroad may be catering to students as global consumers rather than developing them as global citizens (Lewin 2009; Lilley 2014). From the perspective of global citizenship, we are obligated to explore the question of how study abroad programs engage students in critical thinking and nurture a commitment toward responsible social action , ultimately contributing to a more just global community. Unfortunately, students’ sense of superiority of one culture over another may not be challenged and study abroad curricula are often silent on issues of systemic discrimination against non-Western ways of knowing and being. Despite the fact that a majority of study abroad participants come from white , privileged backgrounds (Green et al. 2015) , students often do not expect to analyze, nor are they asked to become more aware of and understand, the implications of their own power and privilege through their study abroad experience. The focus on increasing study abroad participation rates in developed countries may, in fact, lead to a sense of justification, and a reproduction, of existing patterns of power and privilege in the global community (Gorski 2008).

Study abroad is built upon the premise that the “other” exists primarily outside of the boundaries of one’s own country . As previously discussed, one of the strengths of study abroad is that it provides students exceptional opportunities to “become” themselves. However, those who come from more powerful and privileged backgrounds tend to be in control of the rules for engagement in a cross-cultural interaction, which may require already disenfranchised participants to render themselves even more vulnerable. While engaging in cross-cultural dialogue seems to be a logical and beneficial activity during a study abroad program, the opportunity for learning from that dialogue is often not equal (Gorski 2008). Research indicates that participation in cross-cultural interactions can result, in the short term, to changes in attitudes (Dessel et al. 2006 ) ; however, absent from this scholarship is evidence that cross-cultural dialogue contributes to, or even mitigates, systemic inequities (Gorski 2008). In some cases, it may be that study abroad perpetuates a discourse where only less-developed nations are home to poverty or social injustice and a belief that these things could not be experienced in one’s home country (Jorgenson 2014). This lays the foundation for the neocolonial belief that study abroad students are somehow helping developing countries to make progress. Thus, the dogma about the superiority of developed country ideologies and values systems endures, unchallenged.

A prevailing belief among well-meaning attempts to increase study abroad participation rates in developed countries is that the key impediment to involvement in higher education student mobility is a lack of adequate financial resources. This would seem a reasonable assumption, given the evidence to indicate that study abroad participants come disproportionately from privileged backgrounds. Indeed, a national survey of Canadian higher education students found that 70% of respondents who had not participated in study abroad listed a lack of funding as a barrier (Academica Forum 2016). However, the survey data revealed that concerns about study abroad costs did not vary considerably between low and high household income groups. Other research suggests that the profile of a ‘typical’ study abroad participant is a white female from a middle to upper-middle-class home background (Picard et al. 2009; Green et al. 2015 ) . The disproportionately low representation of minority students in study abroad stems, arguably, from the mix of personal and social resources that participants already have packed in their bags as they begin their journeys. Financial security is certainly among these resources, but so too are parental support, international travel experience, personal confidence and resilience , and a belief—though not always well-informed—in the intrinsic value of engaging in an experiential encounter with the “other”. Such resources, as a whole package, are more likely to be found among students from privileged backgrounds than among the more disadvantaged, suggesting that increasing funding for study abroad is just one of several initiatives that need to be undertaken in order to ensure equitable access. A report on the US State Department’s Gilman International Scholarship program , which awards study abroad funding for traditionally underserved undergraduate students, indicates that targeted programs for such minority groups can have a significant long-term impact on participants’ intercultural understanding and career aspirations (Association of American Colleges and Universities 2016). While increasing participation in study abroad would seem to be a worthy goal, it appears that a more nuanced and strategic vision is required if the impact of larger numbers of mobile students is to avoid the pitfalls of reproducing existing power dynamics and further advantaging the already privileged.

Possibilities—Reconciling Paradoxes

Despite the challenges and paradoxes highlighted in this chapter, study abroad professionals, motivated by their responsibility to prepare students for a globalized world, have continued efforts to understand and experiment with program design that activates global citizenship development. Educators may not agree on the exact recipe, but there is consensus that program design must be integrated and that students need to be prepared and supported (Lilley 2014; Vande Berg et al. 2012). While more research is required on why some interventions are more or less effective than others, the following paragraphs highlight promising practices that may allow paradoxes around belonging , risk, and privilege to be reconciled in order for study abroad to be a more effective vehicle for global citizenship education.

Integrated Experiences

Passareli and Kolb (2012) suggest that student learning would be better served if a study abroad experience were considered but one part of a process of global citizenship education rather than being the sole or key means to that end. Immersed and supported in a teaching and learning environment where global citizenship values are embedded throughout their university experience, students are encouraged to think beyond personal experiences, fostering the development of a more than superficial understanding of global values, beliefs and meanings (Tarrant 2010). Scaffolding on this internationalized experience at home, study abroad can be better integrated into the curriculum so that students have the opportunity to apply the learning they have acquired through both coursework and experiential activities (Loberg and Rust 2014).

Theoretical Grounding

As a critical element of international education scholarship and practice, study abroad programs should be underpinned by relevant theories (Deardorff 2016). Often a study abroad program is designed with an itinerary or course content as the predominant consideration. However, adult learning, intercultural competence development, and global citizenship education theories can strengthen program design. Grounding a study abroad program in developmental theories can allow for more personalized learning through acknowledging discrete and measurable levels of learning progress (Bennett 2012; Stuart 2012 ) and provide structure for the development of personal learning goals in an experiential setting (Kolb 2015; Passareli and Kolb 2012). Students not only have the opportunity to learn at a deeper level and increase their knowledge , they also have the opportunity to apply their learning and practice skill development (Deardorff 2016).

A key area for further research relates to the use of theories from non-Western epistemologies that can be used to provide a solid foundation for study abroad programs. Non-western theoretical foundations not only can expose blind spots in Western ways of knowing and being, they can also broaden the possibilities for the interpretation of concepts to the advantage of study abroad students (Deardorff 2016).

Relationships with Role Models

In her comparison of the expatriate experience to a fabled “hero’s journey,” Joyce Osland (2000) describes the critical role of “magical friends” (guides, teachers, country nationals or fellow expats). These role models provide moral support and guidance to expatriates through relationships that involve sharing of questions and information. While different from expatriates, study abroad students likewise need supportive and motivational relationships. As mentors to students for whom the goal is the development of global citizens, educators in these roles must be motivated by social and ethical values (Lilley 2014). Also required are skills in creating a safe space within which to challenge students to consider and imagine alternate paradigms and perspectives. Continuous professional development is needed for educators to be as prepared and effective as possible in facilitating the process of global citizenship learning (Vande Berg, et al. 2012).

Not all “magical friends” of study abroad participants will be educational institution employees. In his study of outbound students, Killick (2012) notes the importance of a “significant other” in several students’ experiences. While the relationships students formed with these “significant others” could not be predicted, they were critical in enabling students to be able to see-themselves-in-the-world.

Reflective Practice

Increasingly, educators are integrating reflective practice into study abroad programs (Biagi et al. 2012; Vande Berg et al. 2012). Students have been shown to learn and develop more as a result of a sojourn when they have been prepared to be more self-reflective and are provided consistent opportunities for reflection (Vande Berg et al. 2012). To make meaning of their experiences study abroad students need opportunities to explore and question their preconceptions and to revisit experiences in light of additional context and knowledge (Kolb 2015; Bennet 2012). Whether reflective practice needs to be primarily formal (e.g. reflective writing, structured debriefs) or a mix of formal and informal (e.g. blogs and serendipitous conversations) will depend on the program structure and educational context, as will the timing of reflection opportunities. How we process, and what we learn from past experiences determines how future choices and decisions are made (Kolb 2015). Therefore, reflective practice during study abroad can provide critical starting points that direct students toward future global citizenship learning opportunities.

Provide Global Citizenship and Intercultural Competence Language and Concepts

In the fields of both global citizenship education and intercultural competence development, there is a call for educators to provide students with language and concepts, a schema or lens, they can use to make meaning of their study abroad experience (Bennet 2012; Lilley 2014). This schema provides the hooks on which learners can hang their study abroad experiences and interpret them at increasing levels of complexity (Passareli and Kolb 2012). Learning outcomes often use explicit language about (for example) intercultural awareness or global citizenship, yet students are often not provided a definition of such terms, nor the context within which the definitions were created. Similarly, students are left to organize the perception of their experiences informed only by the schemata of their own culture or one haphazardly created through previous experience (Bennett 2012). Students need to receive explicit information before, during and after their study abroad experience that allows them to develop an understanding of terminology and key concepts for intended learning outcomes to have a greater probability of leading to the transformative learning they describe.

Acknowledging Power and Privilege at Play in the Study Abroad Experience

If a goal of study abroad is to play a part in developing a global citizen who is inspired to engage in responsible social action , then programs must involve opportunities for students to critically analyze power and privilege in the context of their experience. To achieve this, educators and administrators who provide support to students need to be socially and ethically motivated and articulate (Lilley 2014) and must be aware of their own power and privilege (Gorski 2008). How students are prepared to conceptualize the other needs to be considered. For example, are students expecting to make the world a better place through showing the other supposedly “better” ways of doing something? Or are they expecting to learn from the relationships they develop with cultural others? In addition to how the other is presented and perceived, Gorski (2008) advocates for facilitating an anti- hegemonic discourse and helping students develop critical thinking skills by analyzing global systems that perpetuate the dominance of Western values and beliefs.

Assessment

Assessment of global citizenship learning can be overwhelming and is fraught with challenges (Deardorff 2009). Driven by a general trend toward assessment in higher education and specific needs to improve programming, to link study abroad activities to intended learning outcomes, and to promote student-centered learning through reflective feedback, administrators and educators are beginning to integrate purposeful assessment into study abroad (Vande Berg et al. 2012).

To begin the assessment process, there needs to be clarity on the purpose of the assessment and confidence in the appropriateness of the learning outcomes. The goals of the assessment and how it will be used/shared will also provide direction as to what kind of assessment techniques to employ. While the reliability of various assessment methods is not always agreed upon, research suggests that using multiple methods, including both quantitative and qualitative assessment, is the most effective (Deardorff 2009). An increasingly common practice is the use of psychometric tools with pre- and post-test timing to measure student development of particular mindsets or competencies. 1 Additional forms of assessment used in study abroad include reflection papers, journaling, capstone projects, portfolios, focus groups, interviews (in person and via Skype ), and documentation of discussions and observations of student behavior (Deardorff 2009).

Integrating assessment into study abroad requires time and resources, both in the planning and implementation as well as in analyzing and sharing the data collected. Putting such effort into developing and sharing effective assessment is critical to improving study abroad programs and to documenting their role in developing global citizens (Deardorff 2009).

Notes

-

1.

A list of instruments is in Paige, M. (2004) Instrumentation in intercultural training. In D. Landis, J.M. Bennett, and M.J. Bennett. (Eds.) Handbook of Intercultural Training. CA: Sage.

References

Academica Forum. (2016). Why don’t more Canadian students study abroad? Retrieved from: http://forum.academica.ca/forum/why-dont-more-canadian-students-study-abroad.

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Mass: Addison-Wesley. Association of American Colleges & Universities (2016). Facts & figures—International experiences have lasting impact on traditionally underserved students. AAC&U News, June/July. Retrieved from: https://www.aacu.org/aacu-news/newsletter/facts-figures-international-experiences-have-lasting-impact-traditionally.

Barnett, R. (2004). Learning for an unknown future. Higher Education Research & Development, 23(3), 247–260.

Bennett, M. (2012). Paradigmatic assumptions and a developmental approach to intercultural learning. In M. Vande Berg, R. M. Paige, & K. H. Lou (Eds.), Student learning abroad: What our students are learning, what they’re not, and what we can do about it (pp. 90–114). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Biagi, F., Bracci, L., Filippone, A., & Nash, E. J. (2012). Instilling reflective intercultural competence in education abroad experiences in Italy: The FICCS approach + reflective education. Italica, 89(1), 21–33.

Byers, M. (2005). Are you a ‘Global Citizen’? The Tyee. Retrieved from: https://thetyee.ca/Views/2005/10/05/globalcitizen/.

CBIE. (2016). Canada’s education abroad lexicon. Retrieved from: http://cbie.ca/media/policy-statements/canadas-education-abroad-lexicon/.

Chieffo, L., & Griffiths, L. (2009). Here to stay: Increasing acceptance of short-term study abroad programs. In R. Lewin (Ed.), The handbook of practice and research in study abroad higher education and the quest for global citizenship (pp. 365–380). N.Y: Routledge.

Coryell, J. E., Spencer, B. J., & Sehin, O. (2014). Cosmopolitan adult education and global citizenship: Perceptions from a european itinerant graduate professional study abroad program. Adult Education Quarterly, 64(2), 145–164.

Davies, I., & Pike, G. (2009). Global citizenship education: Challenges and possibilities. In R. Lewin (Ed.), The handbook of practice and research in study abroad higher education and the quest for global citizenship (pp. 61–78). N.Y: Routledge.

Deardorff, D. K. (2009). Understanding the challenges of assessing global citizenship. In R. Lewin (Ed.), The handbook of practice and research in study abroad higher education and the quest for global citizenship (pp. 346–364). N.Y: Routledge.

Deardorf, D. K. (2016). Key theoretical frameworks guiding the scholar-practitioner. In B. Streitweiser & A. Ogden (Eds.), International education, in international education’s scholar-practitioners bridging research and practice (pp. 241–261). Oxford: Symposium.

Dessel, A., Rogge, M., & Garlington, S. (2006). Using intergroup dialogue to promote social justice and change. Social Work, 51(4), 303–315.

Green, W., Gannaway, D., Sheppard, K., & Jamarani, M. (2015). What’s in their baggage? The cultural and social capital of Australian students preparing to study abroad. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(3), 513–526.

Gorski, P. C. (2008). Good intentions are not enough: A decolonizing intercultural education. Intercultural Education, 19(6), 515–525.

Gribble, C., & Tran, L. (2016). International trends in learning abroad. International Education Association of Australia.

Hammer, M. R., Bennett, M. J., & Wiseman, R. (2003). Measuring intercultural sensitivity: The intercultural development inventory. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 27(4), 421–443.

Jones, S. (2008). Student resistance to cross-cultural engagement. In S. R. Harper (Ed.), Creating inclusive campus environments for cross-cultural learning and student engagement (pp. 67–86). USA: NSPA.

Jorgenson, S. R. (2014). (De)Colonizing global citizenship: A case study of north american study abroad programs in Ghana (Unpublished Doctoral Thesis). Retrieved from: https://era.library.ualberta.ca/files/gm80hw49z/JorgensonShelane_Spring%202014.pdf.

Killick, D. (2012). Seeing-ourselves-in-the-world: Developing global citizenship through international mobility and campus community. Journal of Studies in International Education, 16(4), 372–389.

Kolb, D. (2015). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Retrieved from: http://ptgmedia.pearsoncmg.com/images/9780133892406/samplepages/9780133892406.pdf.

Lewin, R. (2009). The quest for global citizenship through study abroad. In Lewin, R. (Ed) The handbook of practice and research in study abroad higher education and the quest for global citizenship (pp. xiii–xxii). NY: Routledge.

Lilley, K. (2014). Education global citizens: Translating the idea into university organisational practice. International Education Association of Australia, Discussion Paper 3.

Lilley, K., Barker, M., & Harris, N. (2015). Exploring the process of global citizen learning and the student mind-set. Journal of Studies in International Education, 19(3), 225–245.

Loberg, L., & Rust, Val D. (2014). Key factors of participation in study abroad: Perspectives of study abroad professionals. In B. Stretwieser (Ed.), Internationalisation of higher education and global mobility (pp. 301–311). Oxford: Symposium.

Macready, C., & Tucker, C. (2011). Who goes where and why? An overview and analysis of global educational mobility. New York: The Institute of International Education.

McBride, K. (2016). The state of internationalization in Canadian higher education. International Higher Education, 86, 8–9.

Osland, J. S. (2000). The journey inward: Expatriate hero tales and paradoxes. Human Resource Management, 39(2–3), 227–238.

Passareli, A., & Kolb, D. (2012). Using experiential learning theory to promote student learning and development in programs of education abroad. In Vande Berg, et al. (Eds.), Student learning abroad: What our students are learning, what they’re not, and what we can do about it (pp. 137–161). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Picard, E., Bernadino, F., & Ehigiator, K. (2009). Global citizenship for all: Low minority student participation in study abroad—seeking strategies for success. In R. Lewin (Ed.), The handbook of practice and research in study abroad higher education and the quest for global citizenship (pp. 321–345). N.Y: Routledge.

Pike, G., & Selby, D. (1988). Global teacher, global learner. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Savicki, V. (2012). The psychology of student learning abroad. In Vande Berg et al. (Eds.), Student learning abroad: What our students are learning, what they’re not, and what we can do about it (pp. 215–237). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Stuart, D. (2012). Taking stage development theory seriously implications for study abroad. In Vande Berg et al. (Eds.), Student learning abroad: What our students are learning, what they’re not, and what we can do about it (pp. 61–89). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Tarrant, M. A. (2010). A conceptual framework for exploring the role of studies abroad in nurturing global citizenship. Journal of Studies in International Education, 14(5), 433–451.

Vande Berg, M., Paige, R. M., & Lou, K. H. (2012). Student learning abroad paradigms and assumptions. In Vande Berg, M., et.al. (Eds.) Student learning abroad: What our students are learning, what they’re not, and what we can do about it. Sterling (pp. 3–28). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Zemach-Bersin, T. (2009). Selling the world: Study abroad marketing and the privatization of global citizenship. In R. Lewin (Ed.), The handbook of practice and research in study abroad higher education and the quest for global citizenship (pp. 303–320). N.Y: Routledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Pike, G., Sillem, M. (2018). Study Abroad and Global Citizenship: Paradoxes and Possibilities. In: Davies, I., et al. The Palgrave Handbook of Global Citizenship and Education. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-59733-5_36

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-59733-5_36

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-137-59732-8

Online ISBN: 978-1-137-59733-5

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)