Abstract

This chapter provides: (1) an overview of the statistical systems and methods of maintaining population statistics in the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation: (2) population statistics in territorial units comparable to the Russian Federation based on primary materials; and (3) a general view of long-term population dynamics from the late imperial era to the new Russian Federation. There is a large gap between research dealing with population during the imperial period and that which examines the period after the October Revolution, since few studies utilized primary data in investigating population figures of the imperial era.

Revised from Russian Research Center Working Paper Series, No. 2, pp. 1–38, December 2007, “Long-Term Population Statistics for Russia 1867–2002” by Kazuhiro Kumo, Takako Morinaga and Yoshisada Shida. With kind permission of the Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University, Japan. All rights reserved.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

2.1 Introduction

This chapter offers an overview of the statistical systems and methods of compiling population statistics used in imperial Russia, the Soviet Union, and modern Russia. It compiles population statistics from primary sources for the territory covered by modern Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union and it identifies long-term population dynamics from the mid-nineteenth century, covering the last days of imperial Russia up to modern Russia.

Most population studies that have looked at both imperial and Soviet Russia have focused their research on one of the periods, covering the other by reviewing other research (Lorimer 1946; Heer 1968; Simchera 2006; Vishnevskii 2006). In most cases, the imperial era is treated as a single period, while the period after the revolution is treated as another (Vodarskii 1973; Kabuzan 1963; Rashin 1956; Zhiromskaia 2000). There are good reasons why previous research has dealt separately with imperial Russia and the post-revolution Soviet Union given that they used different systems for gathering and compiling statistics, and that they covered different territory. However this chapter is does not suffer from such limitations.

Previous research shows that this situation has clearly been a major obstacle to tracing the economic development of Russia through its entire history. It may actually be impossible to examine the modern development of Russia without looking at the imperial era. 1 After all, the imperial era paved the way for the industrialization that occurred in the Soviet Union, which suggests that any investigation into the long-term dynamics of Russia needs to begin with the compilation of statistics from primary sources.

This chapter represents the first attempt of its kind to compile population statistics on the territory covered by modern Russia that date back as far as the nineteenth century, using as many primary sources from imperial Russia as could be collected. A study like this is only possible now that Russia has emerged from the collapse of the Soviet Union. The authors take into account the differences in territory covered by imperial, Soviet, and post-Soviet Russia as they make their own estimates. They also survey population statistics for the territory covered by the present Russian Federation, which were extremely difficult to gather.

This chapter is organized as follows. After carrying out a literature survey that shows the gap between previous research covering the imperial Russian period and that which covers the Soviet and post-Soviet eras, and the paucity of previous research based on original materials, the authors then turn their attention to how the system for gathering and compiling population statistics in the Russian Empire was established.

Although the first, and last, population census of imperial Russia was conducted in 1897, Japan had carried out its first such census more than 20 years later, and population surveys of various kinds had been carried out before that. While the precision of such surveys is not generally thought to be high (MVD RI 1858; Rashin 1956), 2 they are at least useful for gauging population dynamics.

This chapter then looks at population statistics from post-revolution Soviet Russia and modern Russia. It would be impossible to list here all the problems involved in compiling statistics from the Soviet era, but chief among them are: that the country was a battlefield during World War I; the civil war and incursions by foreign powers that followed the Russian revolution of 1917 (1918–1922); the frequent changes in administrative regions and the numerous famines between 1920 and 1930; the Great Purge of the Stalin era (1936–1940) and the suppression of statistics that accompanied it; and World War II and its aftermath, during which invasion forces temporarily captured the whole of the Ukraine, advanced as far as the suburbs of Moscow, and surrounded Leningrad (now St. Petersburg). The numerous problems with Soviet statistics are well documented, and these problems also affect the most basic statistics of all, population statistics.

The first challenge was to link population statistics from imperial Russia with those from Soviet Russia, and then adjust these statistics to make them correspond to the territory covered by modern Russia. Because the borders of administrative divisions in imperial Russia were not the same as those during or after the Soviet era, the authors needed to start by solving this problem. In particular, they needed to take account of differences in the volume of statistics compiled during the imperial era for European Russia, Siberia and the Russia’s far east, and the Caucasus. With these problems in mind, this chapter set about compiling basic population statistics with the primary aims of: (1) relying on primary historical materials to gather as many statistics as possible for a 100-year period; and (2) attempt to harmonize them with the territory covered by modern Russia to the greatest extent possible. The purpose was to gather the most basic information required to track the development of Russia throughout its history.

2.2 Previous Research on Long-Term Russian Population Dynamics and Statistics

2.2.1 Population Research on the Imperial and Soviet Eras

Surprisingly little research has been conducted on the compilation of long-term population statistics in Russia. Obviously, a major factor behind this paucity of research is the fact that the Russian Federation only became an independent nation, with its current territory, a quarter century ago. Even so, it is striking that many studies, even those supposedly attempting to explore the imperial and Soviet eras in an integrated fashion, have ignored the fact that the territory covered by Russia has changed, and that so few studies have been based on primary historical materials.

This section summaries the previous studies. Studies of population dynamics in the imperial era used various population surveys and official statistics. Notable among them are those of Koeppen (1847), Den (1902), and Troimitskii (1861), which were based on household censuses (reviziia), discussed later in this chapter. Although population surveys were conducted several times, each of these studies relied on data from only one survey, so they do not provide any clues to population dynamics. 3 In addition, they only cover the population and social structure for males basically.

In the Soviet period a lot of research on population history has been conducted. Studies by Rashin (1956), Kabuzan (1963, 1971), and Vodarskii (1973) provide broad coverage of the imperial era. The study by Vodarskii (1973) covers 400 years from the sixteenth century to the early twentieth century, but basically represents a compilation of secondary sources and previous research. Kabuzan (1963, 1971) bases his research on primary sources, such as household censuses, and explores the dynamics and social organization of the male population from the beginning of the eighteenth century to the middle of the nineteenth century. One useful thing he does do is put together tables of data from all the household censuses. However, most worthy of note is the study by Rashin (1956), in which he uses data that was published by the Ministry of the Interior’s Central Statistical Committee (described later) almost without a break from the mid-nineteenth century to compile population statistics on the period from then up until the end of the imperial era. Of all the research on population in Russia, Rashin’s 1956 study is frequently referred to for its description of the imperial era. 4

In studies of population dynamics in the Soviet era, it is not surprising at all that the scope of inquiry of the majority of such studies is not the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic, but the Soviet Union as a whole (Podiachikh 1961; Gozulov and Grigor’iants 1969, etc.). However, during the Soviet era it was extremely difficult to conduct research on the most vexing periods of Soviet population history, such as the chaos just after the revolution, the Great Purge, and World War II, because of the lack of opportunities to examine historical materials.

Among historical research conducted in Europe and North America, there is, as might be expected, a huge volume of literature on specific regions in Russia. If our discussion is limited to research covering the late imperial era to the period after the socialist revolution, the studies of Lorimer (1946) and Heer (1968) need to be mentioned. Lorimer’s (1946) work is a painstaking attempt to trace economic development and population dynamics in the Soviet Union as a whole from the end of the imperial era to World War II. Because the study was not made with the aim of compiling statistics, it does not take adequate account of territorial adjustments or extract enough data from primary sources. Heer (1968) used secondhand references from various previous studies to compile dynamic statistics on the period from 1861 to 1965. Coale et al. (1979) only compare dynamic statistics in 1897, 1926, and 1959, years in which a population census was carried out, and base their study on the use of primary statistics. However, they do not attempt to differentiate between the territory covered by the imperial and Soviet eras. Clem’s (1986) is a general discussion of all the censuses conducted between 1897 and 1979, and provides a useful list of almost all official publications relating to population censuses.

For the current chapter, Leasure and Lewis’s (1966) study proved extremely useful. They focused on the population censuses carried out in 1897 and 1926 and estimated population statistics for each region, using the Soviet administrative divisions as of 1961, with a map showing the administrative divisions in 1897 and one of the same scale for 1961 and stating what percentage of each province in the imperial era is included in each of the 1961 administrative divisions. 5 , 6 Although the use of this method casts doubts over the accuracy of the study’s findings, it is worth mentioning that the difference between the areas of each region estimated using the method and the official areas as of 1961 are within 2 % of the areas of each region. 7

2.3 Recent Research Trends

A lot of new research has been conducted since the end of the Soviet era and the birth of the new Russia. This section mentions some studies that, like this chapter, have attempted to grasp the long-term dynamics. Since 2000, voluminous works on long-term dynamics have been published. Simchera (2006) provides a comprehensive treatment not just of the demographics, but of the Russian economy as a whole over the last 100 years. However, while Simchera’s book features numerous tables of statistics, the views expressed and the data itself are basically just a review of previous research. In addition, its descriptions of its data sources are extremely vague, which casts significant doubt over their verifiability and makes it extremely difficult to assess or critique it. Vishnevskii (2006) uses dynamic statistics to focus on population changes over a 100-year period. For the imperial era he uses statistics for the whole of European imperial Russia, while for the Soviet era and beyond he adjusts statistics to match the territory covered by modern Russia—an inconsistency which needs to be mentioned. Like Simchera (2006), Vishnevskii (2006) relies entirely on previous research for statistics on the World War II period, and for the imperial era he uses data from Rashin (1956) to compare demographic shifts in Russia with those in various other countries. Although these studies do not constitute a systematic survey of population statistics, the insights they afford are valuable. However, the fact that neither study makes use of primary historical materials does raise questions.

Goskomstat Rossii (1998) is a publication that focuses on re-compiling population statistics from the Russian Federation State Statistics Committee (now the Federal State Statistics Service) for the 100-year period from 1897 to 1997 to match the territory covered by modern Russia. Some of its content may therefore overlap with this chapter. However, a close examination of the details reveals a lack of explanation for matters such as the methods of calculation employed and the assumptions upon which the calculations were based. 8

Because it has become much easier to access archived historical materials since the collapse of the Soviet Union, a lot of research has been being carried out on population dynamics for hitherto inaccessible periods such as the Great Purge and World War II. With focused studies like this, careful attention is paid to making adjustments for differences in territory and investigating the basis for calculations. Studies of this type worth mentioning include that of Zhiromskaia (2000), which deals with early Soviet Russia, and that of Poliakov and Zhiromskaia (2000, 2001), which is based on sources such as documents in the national archives. The former limits itself to examining the results of the 1926, 1937, and 1939 population censuses. 9 Because of limitations on the historical materials used and the years to which they relate, much of the research it contains covers the whole of the Soviet Union. The latter was not conducted for the purposes of obtaining a macroscopic view of population dynamics. Rather, it constitutes a collection of essays on specific topics that could not be studied during the Soviet era because the information was not publicly available. The topics covered include the results of the secret census conducted during the Stalin era, the make-up of the labour camp prisoner population, and population dynamics during World War II. Andreev et al. (1993) studied the Soviet Union as a whole from the period before the war right through to the collapse of the Soviet Union. Their estimates relating to population dynamics in the 1920s, which are based on archive materials, are of particular interest. In a later study (Andreev et al. 1998) archived historical materials were used to unearth dynamic statistics for the periods 1927–1939 and 1946–1949, when hardly any official statistics were published, and presented their estimates using multiple time series. They attempted to make territorial adjustments and gave relatively detailed information on their data sources, so their figures are verifiable to an extent. Population dynamics during the 1920s and 1930s were discussed by Rosefielde (1983), Wheatcroft (1984, 1990), Anderson and Silver (1985), and many others. However, Andreev et al. (1998) is the most important of all studies in exploring the periods of collectivization, the Great Purge, and the lead-up and aftermath of World War II. 10

This section has mentioned a limited number of studies on the demographics of imperial and Soviet Russia, and there are numerous other studies from Europe and North America on Russian demographics. However, access to original historical materials from the Soviet era is a major problem, and this has probably hindered the compilation of long-term data. In addition, the modern Russian Federation has only existed as an independent nation since the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of 1991, so it is not surprising at all that no systematic study has been made of its population. Nevertheless, as this section has seen, previous research has failed to make territorial adjustments, even though this would not have been impossible even in the Soviet era, and has not sought to base itself on primary historical materials from the imperial era up to the end of the Soviet era.

2.4 Russian Population Statistics

2.4.1 Household Censuses (Reviziia) in Imperial Russia

Population surveys have a long history in Russia. It is widely known that household censuses, called reviziia (revisions), of people liable for taxes began with an order (ukaz) issued by Tsar Peter I on November 26, 1718 (Herman 1982; MVD RI 1858). 11 Reviziia were conducted on ten occasions, once every 10–15 years, until 1857–1858. However, it is also well documented that they were beset with a wide range of problems, such that their accuracy is strongly in doubt (MVD RI 1858; Rashin 1956). Many of these problems lie in the fact that any census that targets people liable for taxes will obviously be prone to inaccuracy.

The main objectives of these population surveys were to identify people who should pay taxes and to secure personnel for the army. The backdrop to this was that household-based taxation had been replaced with personal taxation (a poll tax), which made it necessary to identify the whole population (Herman 1982; MVD RI 1858, 1863). 12 In the beginning, the surveys were conducted under the leadership of the tax authorities (kammer-kollegiia). Anyone identified during the surveys would immediately assume an obligation to pay taxes, which meant that huge numbers of people tried to avoid being registered. Such behaviour was subject to penalties, such as penal servitude and fines, but this just encouraged people who had avoided registration to continue to do so. In 1721 an imperial edict was issued whereby people who had hitherto avoided registration would not be subject to punishment if they now agreed to register, and at the same time the poll tax was reduced. After that, the censuses began to reflect actual populations more accurately (MVD RI 1858, 1863).

Only men were liable for taxes, and the surveys only covered individual farmers, merchants, and traders designated as taxpayers. However, there was a plan to include women, who were not liable for taxes, in the statistics. And the household censuses included non-taxpayers such as members of the clergy, stagecoach drivers, and retired soldiers as well. However, a shortage of personnel to conduct the surveys, financial limitations, and the vastness of the land made it difficult to make the surveys comprehensive. No surveys of Poland, Finland, or the Caucasus were made, and there are hardly any records for members of the aristocracy (dvoriane) or government officials. Women were not recorded in the first, second, or sixth censuses. Only with the ninth household census of 1850–1851 were non-taxpayers such as aristocrats and government officials finally included (MVD RI 1858, 1863; Valentei 1985).

2.5 Compilation of Population Statistics by the Central Statistical Committee of the Ministry of the Interior

Imperial Russia began putting together a system for gathering and compiling statistics in the first half of the nineteenth century. In 1834 a Statistical Section (statisticheskoe otdelenie) was established within the Council of the Ministry of the Interior (sovet ministerstva vnutrennikh del), 13 and surveys and statistics at city or provincial (province = guberniia) levels began to be published. In 1853 the Statistical Section at the Council of the Ministry of the Interior was merged with the tax office’s Interim Lustration Committee to form the Statistical Committee of the Ministry of the Interior (statisticheskii komitet ministerstva vnutrennikh del). Then on March 4, 1858 the Statistical Committee of the Ministry of the Interior was reorganized as the Central Statistical Committee (tsentralnii statisticheskii komitet) to build a systematic foundation for the compilation of statistics. 14 Because the gathering of information by the statistical committees established for each province was inadequate, the Central Statistical Committee established two divisions, the Statistical Division and the Regional Division (zemskii otdel). From then on a system centering on the Central Statistical Committee was put in place for the compilation of statistical data at the national level (MVD RI 1858, 1863; Goskomstat Rossii 1996). 15

The Central Statistical Committee of the Ministry of the Interior not only used data from the household censuses (reviziia) described in the previous section to compile its population statistics. It also had to refer to parish registers, to compile statistics on births and deaths, and documents from police surveys, which were essential for obtaining figures for followers of each religion.

The parish registers (metricheskie knigi) were based on documents recording confessions 16 (ispovedanie) to the Russian Orthodox Church. These documents include records of each year’s births, deaths, and marriages. Once a year, on February 1, following orders from the religious affairs division, the provincial governor would collect these figures and include them in the population schedule that was attached to a report sent to the tsar (MVD RI 1858, 1863). 17

The number of births, deaths, and marriages among followers of other religions or sects, such as Roman Catholics, Protestants, Jews, and Muslims, were supposed to be reported to the local authorities by the heads of each parish (MVD RI 1863). 18 However, this does not allow one to grasp the numbers and demographics of worshippers who were not tied to any specific church, or separatists from the Orthodox Church (the Old Believers). 19 The ethnic and religious diversity in Imperial Russia, and the presence of a distinctive Russian separatist sect had a major impact on the accuracy of population statistics, one that was impossible to ignore. Therefore, to supplement this kind of information administrative-police surveys (administrativno-politseiskii perepis) were also referred to. These surveys were conducted by the police or administrative offices in each district using the list of dwellings from the household census. 20 This allowed newborn babies, recently deceased persons, and people who had moved in or out of the area to be added to or deleted from the census records. Because these surveys were not based on religion they contained figures that could not be obtained from the parish registers.

Population statistics were compiled by adjusting the figures for births, deaths, and movements from the last household census, conducted in 1858, obtained from the various records described above (MVD RI 1858, 1863; Goskomstat Rossii 1996). Following the issuance of an imperial order in 1865, 21 the religious affairs division, as mentioned earlier, had provincial statistical committees draw up and submit lists of residents compiled from parish registers. This meant that while statistics on population dynamics were recorded from 1867 onwards, they lacked details such as age, which soon led to a realization that there was a need to obtain population data through surveys (MVD RI 1890). However, it was not until 1897 that the first national population census since the household censuses ended in 1858 was carried out. This was imperial Russia’s first and last population census. 22

2.6 Statistical Organization and Population Statistics in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia

After the 1917 revolution the economic system was rapidly reorganized, and the system for compiling statistics was also reformed in various ways. Although the Supreme Council of People’s Economy (VSNKh: Visshii sovet narodnogo khoziaistva), which was formed just after the revolution in December 1917, had a statistics and population survey department, in July 1918 the Central Statistical Board (TsSU: Tsentralnoe statisticheskoe upravlenie) was established with the aim of centralizing the compilation of statistics. 23 This was followed by the establishment of regional branches in September of the same year. 24 In addition, companies and organizations were required to submit to the Statistical Board information it deemed necessary and comply with orders it issued. Right from the beginning, however, the priority was not to ensure independence in the process of compiling statistics, but to facilitate economic planning, and the Statistical Board was therefore put under the control of what was then the People’s Council (Popov 1988; Yamaguchi 2003). Then, in 1923, just after the civil war, the Central Statistical Board was attached to the Soviet Union Council of People’s Commissars. 25 Despite this arrangement, the post-revolution civil war and incursions by foreign powers meant that in the early 1920s it was impossible to gather business or census statistics covering all Soviet territory. 26

The watershed year for the system for compiling statistics was 1930. In January of that year the Central Statistical Board became a department of the State Planning Commission (Gosplan) (Goskomstat Rossii 1996). The department’s role was clearly based on the premise that the system for compiling statistics should contribute to economic planning. In 1931 the name of the Central Statistical Board was changed to the Central Administration of Economic Accounting of Gosplan (TsUNKhU Gosplana: Tsentralnoe upravlenie narodnokhoziaistvennogo ucheta), and from 1941 to 1948 was known as the Central Statistical Board of Gosplan (TsSU Gosplana) (Goskomstat Rossii 1996). Yamaguchi (2003) pointed out, probably correctly, that these reforms were carried out because during the rapid industrialization that occurred before World War II, particularly during the five-year plan that started in 1928, the existence of an independent statistical organization would have resulted in the emergence of a gap between the producers and users of statistics, and that this would have hindered the successful implementation of the economic plans.

Later, in 1948, the Board was separated from Gosplan and became the Central Statistical Board under the Council of Ministries of the USSR, and then in 1978 achieved independence as the Central Statistical Board. The Board has continued to conduct activities ever since and, following several name changes, is, at the time of publishing this volume in 2016, known as the Russian Federal State Statistics Service. The methods used for collecting and producing statistics are basically the same in the modern Russian Federation as they were in the Soviet era and characterized by centralization. Statistics were not produced by individual ministries and agencies. Rather, each ministry and agency provided statistical reports on corporations and organizations to the Central Statistical Board, which then compiled statistics from these reports (Goskomstat Rossii 1996). However, because the country’s transition to a market economy following the collapse of the Soviet Union resulted in profound changes in the forms of corporations and the structure of industry, the old method of putting together production and other statistics, which centered on reports produced by individual business units, has clearly become less effective (Yamaguchi 2003). This has led to the introduction of the Unified State Directory of Enterprises and Organizations (EGRPO: Edinii gosudarstvennii registr predpriiatii i organizatsii) (Goskomstat Rossii 2001; Yamaguchi 2003) as part of a series of systematic reforms ti enhance statistical precision.

In 1920, less than three years after the revolution, the Soviet Union carried out its first population census to provide basic data for the implementation of the State Plan for the Electrification of Russia (GOELRO: Gosudarstvennii plan elektrifikatsii Rossii), which was a precursor to the five-year plans. However, with the post-revolution civil war still raging, the census had to be limited to the European parts of the Soviet Union. It was the 1926 census that became the first to cover the whole of the Soviet Union. In 1937 the first population census after the launch of the five-year plans was conducted. However, because the results showed the impact of the 1930s collectivization of agriculture and the major famines that followed, and the Great Purge, which began around 1935, they were kept on file at the Central Statistical Board and were not published. The 1939 census represents the last truly usable census from before World War II. 27 The first population census after World War II was conducted in 1959. Censuses were then carried out in 1970, 1979, and 1989, 28 and the first population census of modern Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union at the end of 1991 took place in 2002.

Russian civil law contains provisions concerning the recording of population dynamics in each calendar year, such that citizens are required, and have been since the Soviet era, to notify the Division for Questions of Registration of Vital Statistics—known as ZAGS (Otdel zapisi aktov grazhdanskogo sostoianiia), an organization that handles the registration of births, deaths, and marriages—of any such changes. 29 The system remained unchanged after the collapse of the Soviet Union, with families obliged to report births within one month, and deaths within three days to ZAGS. 30 Residency registration (propiska), including the registration of interregional migration, had be done at local branch offices of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. 31 Using the data gathered from this system, population statistics have been produced and published annually since 1956 in The National Economy of the RSFSR (Narodnoe Khoziaistvo RSFSR), a collection of official statistics. 32 Of course, it was impossible for residency registration alone to fully capture interregional migration and accurately record regional populations. It also should be mentioned that in the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic during the Soviet era, 0.75 % of the population was revised as being unregistered during the period between the 1959 population census and the 1970 census 11 years later (Kumo 2003).

2.7 Processing of Russian Population Statistics

2.7.1 Population Statistics from Imperial Russia

As mentioned earlier, no household censuses, which were designed to calculate the population of people liable for taxes, were conducted after 1858. This meant that the task of producing statistics shifted away from agencies under the jurisdiction of the tax authorities, which, it is fair to say, laid a foundation for improving statistical accuracy. In 1858 and 1863 the Central Statistical Committee of the Ministry of the Interior experimented with producing various statistics based on data, such as that from the household census. Then, from 1866, it began to compile and publish statistics, initially intermittently but later on a continuous basis.

The statistics from imperial Russia contained in this chapter were extracted from the series of official statistics published between 1866 and 1918.

Using data presented in sections such as “Population Dynamics in European Russia in the Year ****” (Dvizhenie naseleniia v evropeiskoi Rossii ** goda) from Central Statistical Committee publications entitled the Statistical Bulletin of the Russian Empire (Statisticheskii vremmennik Rossiiskoi Imperii), published intermittently between 1866 and 1897, and Statistics of the Russian Empire (Statistika Rossiiskoi Imperii), published between 1887 and 1916, it is possible to obtain figures for the period to 1910 for the numbers of births, deaths, infant deaths, and rates of these per 1,000 people for 50 provinces in imperial European Russia. 33 Total population (by province) is presented in some years and not in others. Statistics on births and deaths exist, but they cannot be directly relied upon to paint a picture of dynamics after the middle of the nineteenth century. This is because the imperial notion of European Russia differs greatly from the territory covered by modern European Russia or the Soviet era European Russia.

From 1904, statistical yearbooks entitled Yearbook of Russia (Ezhegodnik Rossii) (published between 1904 and 1910) and Statistical Yearbook of Russia (Statisticheskii ezhegodnik Rossii) (published between 1912 and 1918) were published at regular intervals. Because the dynamic statistics on the population of European Russia they presented were probably preliminary, for the period 1904–1910 the authors used the numbers of births, deaths, and infant deaths in sources such as the “Population Dynamics … in the Year ****” section of Statistics of the Russian Empire, which was published a little after the years to which the data it contains relates. However, the Yearbook of Russia and the Statistical Yearbook of Russia are useful in that they record the populations of regions (provinces) and the districts within them not just for European Russia, but for the whole of imperial Russia. However, the question of how accurate these statistics are obviously arises. When the total population of European Russia according the 1897 population census is compared with the total populations extrapolated from the sections on population dynamics in the 1893, 1895, 1896, and 1897 editions of Statistics of the Russian Empire, it is possible to confirm that the disparity is less than 1.5 %. 34 Since the authors judged the statistics were reliable, this chapter uses the following procedure for processing statistics from the imperial era. 35

-

(1)

For imperial European Russia for the period 1904–1916, all the figures for population and numbers of births, deaths, and infant deaths that could be obtained for all the years that had data were sorted by region (gubernias, oblasts, and krais).

-

(2)

Because the national borders of the Russian Federation after the collapse of the Soviet Union do not match the borders of the gubernias, oblasts, and so on of imperial Russia, this chapter used the proportion of the land area of each of the administrative divisions of imperial Russia that was included in the territory of the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic (RSFSR), (i.e., the territory of the present Russian Federation, as produced by Leasure and Lewis (1966)), to calculate populations and numbers of births, deaths, and so on for each region. The author then added up the totals to estimate figures for the European part of the present Russian Federation. 36

-

(3)

The problem was how to handle the Caucasus, Siberia, and the Russia’s far east, because no dynamic statistics were published on these regions during the imperial era. The same is true for the portion of imperial Russian Finland that is included in the present Russian Federation, though the total population of this region could be obtained for 1885 and 1904–1916. Looking at the regional distribution of the total population of imperial Russia using the method described in (2), one can see that the total population of the Caucasus, Siberia, the Russia’s far east, and the portion of Finland described above as a percentage of the total population of the territory of the present Russian Federation was no more than 21.3 % in any of the years between 1885 and 1916 for which figures could be obtained, and about four-fifths of the total population of these regions resided in European Russia. 37 Given this situation and to grasp the overall trend the figures for the crude birth, death, and infant mortality rates obtained in (2) for the European part of the present Russian Federation were applied to these territories outside European part of the Russian Empire. The crude birth, death, and infant mortality rates for European Russia were applied to the 1916 population of the Caucasus, Siberia, and the Russia’s far east (plus part of Finland), calculated using the method described in (2), and were used to go back and calculate populations for previous years.

-

(4)

For the years 1901 to 1903, using the method described in (3) above, this chapter used the crude birth rate, crude death rate, and infant mortality rate for European Russia to go back and extrapolate populations for these years.

-

(5)

Modern Kaliningrad is not included for the imperial era. 38

-

(6)

For reference purposes, the dynamics were also calculated for the years 1891 to 1900 for the regions of imperial European Russia that lie within the European part of the present Russian Federation. The rates of natural increase obtained were then applied to the entire territory, and a time series for total population was produced. This chapter also used crude birth and death rates for imperial European Russia (not the European portion of the present Russian Federation) to go back and extrapolate populations for the years 1867–1890. 39

2.8 Population Statistics in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia and Related Problems

The biggest problem with studying population statistics on post-revolution Soviet Russia is that it is not always easy to get hold of reliable data. Although population censuses were carried out in the early years of the Soviet Union, in 1926, 1937, and 1939, and the first census after World War II was conducted in 1959, it is often impossible to obtain information from official statistics to fill in the gaps between these years. This is especially difficult for the period from 1917 to 1921, when revolution, civil war, and incursions by foreign powers turned the country into a battleground. The same goes for 1941–1945, when the nation was in the grip of World War II. It is also extremely difficult to obtain population statistics on the 1930s, a period marked by the confusion of the collectivization of agriculture and the ensuing major famines, and the Great Purge. In short, hardly any population statistics were published from the end of the 1920s to the beginning of the 1950s. The only pre-1950 figures that could provide a reliable benchmark were often not official statistics, but historical materials from the statistical authorities that can be viewed by examining official archive materials.

Because of this situation, for this chapter the idea of obtaining primary historical materials to make independent estimates of Soviet-era population statistics was abandoned, and the focus became to present as many figures as could be obtained to serve as a basis for such statistics. This chapter used officially published statistics and historical materials from the archives (Russian State Economic Archive, RGAE). 40 From 1956 onwards, statistics were published without a break and it was relatively easy to obtain data dating back to 1950.

Next, changes in administrative divisions and their territories, which occurred after the revolution and around the time the Soviet Union was established in the 1930s and because of World War II, had to be accounted for. Even if the changes that resulted from the war are ignored, a major systemic shift occurred with the establishment of the republics that were to make up the Soviet Union, created for each of the nation’s different ethnic groups. Although it would be impractical to list all the changes, a few points need to be kept in mind. Most of the changes in the 1920s and 1930s were made in accordance with the Soviet Union’s famed “national delimitation” policy of redrawing the boundaries of imperial Russian administrative divisions on ethnic lines, which led to the establishment of republics named after the predominant ethnic group they contained: 41

-

From the establishment of the RSFSR in 1917 until 1936, modern Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan were included in the RSFSR as the Kazakh Autonomous Republic and the Kyrgyz Autonomous Oblast (later the Kyrgyz Autonomous Republic).

-

Modern Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and part of Kazakhstan were included in the RSFSR as the Turkestan Autonomous Republic from the revolution until 1924.

-

Until 1924, the Orenburg Oblast of modern Russia was included in the Kazakh Autonomous Republic described above and, therefore, is included in the RSFSR.

-

In 1924 the Vitsebsk Oblast, now part of Belarus, was transferred from the RSFSR to the Byelorussian Republic. The same thing happened to the Gomel Oblast, also now part of Belarus, between 1924 and 1926.

The above factors need to be taken into account when using statistics from the 1920s and 1930s to derive population statistics for the territory covered by the modern Russian Federation. Care also needs to be taken with factors such as: (1) the treatment of the area around the Karelian Isthmus and the Republic of Karelia of the modern Russian Federation, which were acquired from Finland following the Winter War of 1939–1940 and the Continuation War (1941–1944); (2) the incorporation into the present Ukraine (where it remains) of the Crimean Autonomous Republic (later the Crimean Oblast), which was under the control of the RSFSR until 1954; and (3) the inclusion of the Tyva autonomous republic into the RSFSR, which occurred after 1944.

2.9 Results

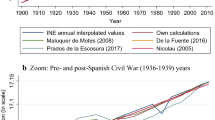

Figures 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 2.4 and Table 2.1 show the results of compiling population statistics on imperial Russia, Soviet Russia, and modern Russia, using the methods described in the previous section. A short summary of the results now follows.

As can be seen from the total population figures in Fig. 2.1, the impact of the Russian Revolution and the turmoil that followed it, and that of World War II, was enormous. Following the revolution in 1917, it took until around 1930 for the population to recover to its pre-revolution level. It was not until 1956 that the population surpassed its level on January 1, 1941, just before the outbreak of the war with Germany. If one compares the population of the territory covered by the present Russian Federation at the end of the imperial era with that in 1946, one sees that nearly 30 years of population growth had been wiped out. Although this is well known to those who study the demographic history of the Soviet Union (see Poliakov and Zhiromskaia 2000, 2001; Vishnevskii 2006), this chapter is the first attempt to produce a population time series for the period up to the 1860s in the late imperial era for the territory covered by the present Russian Federation.

Total population (Notes: The figures for the period during World War II are just rough estimates, because data was lacking for numerous regions. In addition, the figures for 1928–1938 (extrapolated from the population in 1927) and 1945–1949 (extrapolated from the population in 1950) were calculated using the difference between the number of births and deaths, and therefore do not reflect changes caused by social factors such as migration)

As mentioned earlier, it is possible, based on the limited data available, to use the total population and number of births, deaths, and infant deaths at the end of the nineteenth century to go back and extrapolate data for the European part of the present Russian Federation during the imperial era. As described in Sects. 2.3 and 2.4, because figures can be obtained for each of the regions (called gubernias in the imperial era) from 1891 to the early twentieth century, the data for these regions can be considered reasonably accurate. However, the method used in this chapter cannot ensure the accuracy of the figures for the non-European territory of the present Russian Federation.

What is noticeable when looking at Fig. 2.2 is the high crude birth rate in the late imperial era and the slight decline in the crude death rate at the end of that era. 42 These observations have already been made by researchers such as Rashin (1956) and Vishnevskii (2006), but apart from the study by Rashin (1956), no other research has made use of primary historical materials. In fact, most other studies have simply quoted Rashin’s (1956) study. The current chapter, however, proves that Rashin’s (1956) findings were correct. 43 No clear upward or downward trend in the infant mortality rate can be discerned.

Crude birth rate and crude death rate (Notes: Rates for 1867–1890 are for the European part of imperial Russia; rates for 1891–1917 are for the territory of European Russia within the present Russian Federation; rates for 1918–2002 are for the entire territory of the present Russian Federation. Rates for the 1927–1938 and 1942 periods are just rough estimates, because data was lacking for an extremely large number of regions. Figures for 1924–1925 were only calculated for European Russia)

If one now links the imperial and Soviet eras, one can see from Fig. 2.2 that there was a marked decline in the crude birth and death rates before and after the two world wars. This was also pointed out by Vishnevskii (2006). The time series of population during the imperial era was produced simply by invoking the data on crude birth and death rates for the European part of the present Russian Federation (for 1891–1903) and the entire European part of imperial Russia (for the period up to and including 1890). This means that the findings in this chapter, obtained by using rates as the basis for the findings, more or less match the findings of previous research.

For the early Soviet era, this chapter attempted a survey of archived historical materials, but not all the figures needed were found. The notes to Table 2.1 mention that, depending on the year, there were large differences in the accuracy of the data, for example in terms of the regions covered. There was almost no data at all for 1916–1923, which includes the period from the end of the revolution to the conclusion of the civil war, while for 1928–1945 there were numerous regions for which data was lacking. There will obviously be large fluctuations in the figures for these two periods. These were Russia’s most tumultuous periods, so even if data could be obtained it would probably not be particularly reliable. 44 However, if it is admissible to overlook fluctuations caused by external factors, the results of the examination presented in this chapter should be of some help in identifying population trends.

Now to discuss the data for the Soviet era. Apart from the figures for infant deaths between 1927 and 1938, the dynamic statistics presented here are from the same historical materials used by Andreev et al. (1998). As for the infant deaths figures, Andreev et al. (1998) give the source as the Goskomstat SSSR archives, but this cannot be verified because they did not identify the registered number of the materials. The authors therefore conducted their own investigation at other public archives to determine the authenticity of the data. Although the historical materials this chapter used to extract total populations for 1941–1945 partially match those used by Ispov (2001), the figures this chapter presents are different. This is because Ispov (2001) did not make adjustments for places like the Crimean Autonomous Republic (later Oblast), and the authors would like to stress that the figures presented in this chapter are correct as population figures for the territory of the present Russian Federation, excluding regions that were under occupation.

This chapter identified the numbers of births, deaths, and infant deaths during World War II (1941–1945). While Ispov (2001) produced only two- to three-year time series, this chapter presents figures for every year. However, because data is lacking for many regions for this period, it is impossible to use the statistics as they stand. In addition, the crude death rate for regions for which data could be obtained would undoubtedly have been lower than it was for regions for which data is lacking (e.g. regions that were under occupation). So the key problem is the unusually high death rate that one would expect to see in those regions for which data was lacking. In fact, unless the natural rate of increase is a negative figure, whose absolute value is larger than the figure obtained here, it is impossible to explain the decline in total population during World War II. The infant mortality rate jumps in 1943, and archived historical materials support this (Fig. 2.3). Whether or not this reflects reality cannot be determined from the historical materials obtained. If the infant mortality rates for World War II are eliminated, it is possible to discern a major trend (Fig. 2.4).

Infant mortality (excluding archive data for the period of World War II) (Note: Notes are the same as those for Fig. 2.1)

The numbers of births, deaths, and infant deaths for 1946–1949 and the number of infant deaths for 1951–1952, 1955–1957, and 1959 differ from those in the historical materials used by Andreev et al. (1998). Unfortunately, there is no way of ascertaining the causes of these not insignificant differences because the historical materials for 1946–1955 used by Andreev et al. (1998) remain classified. 45 The authors did manage to find dynamic statistics for 1946–1955 by examining declassified historical materials. With regard to this period, it is worth mentioning that the population at the beginning of 1946 and on February 1, 1947 were obtained from archived historical materials, but difficulties were experienced when trying to compare them with the 1950 population as presented in official statistics. 46 This chapter therefore used the number of births and deaths to go back and extrapolate populations for 1946–1949 from the population in 1950.

Finally, the dynamics of modern Russia are well known (Shimchera 2006; Vishnevskii 2006). The rise in the crude death rate since 1991 is particularly striking. In imperial Russia the crude death rate climbed most noticeably in 1891, during which there was a large-scale famine; while the periods in which the crude death rate jumped during the Soviet-era periods for which data were obtainable were 1933–1934, also a time of severe famine, and World War II. That the population dynamics seen in the present Russian Federation since 1991 are unusual is clear for all to see.

2.10 Challenges Remaining

This chapter began with a review of the systems that have been used to compile population statistics in Russia from the imperial era, through the Soviet era, and into the modern Russian era. Next, using primary sources, it went on to estimate and present a time series of the imperial Russian population of the territory covered by the present Russian Federation by adjusting population statistics for imperial Russia to match this territory; and then did the same for the Soviet and post-Soviet eras, basing figures on as many primary sources as were obtainable. The aim was to build a foundation for viewing the populations of imperial, Soviet, and post-Soviet Russia in an integrated way. However, many of the problems could not be solved, and have had to be set aside as requiring further investigation.

-

(1)

Reliability of Imperial-Era Data and Estimates for Non-European Regions of Russia

It is probably inevitable that the accuracy of data from the imperial era is doubtful. Nevertheless, a time series for European Russia that meets certain standards can still be put together, and it is sometimes possible to compare estimates based on dynamic statistics with the figures for total population included in official statistics. A major problem one faces is obtaining, and judging the reliability of, data on regions outside European Russia, such as the Caucasus, Siberia, and the Russia’s far east.

As mentioned earlier, it is almost impossible to get dynamic statistics or total populations for regions outside European Russia in the nineteenth century. From the historical materials examined the authors were able to obtain total populations and dynamics for 1856, total populations for 1858, 47 and total populations for 1885, but their accuracy is open to question. The methods used to prepare population statistics in imperial Russia, described in Sect. 2.5 of this chapter, were also applied to non-European Russia. However, except for some data for 1856, no information on dynamics in the regions outside European Russia was published. Therefore, to produce the long-term time series of population for this chapter, statistics for the European part of imperial Russia were accepted at face value, though they do need to be re-examined. It will also be necessary to try and find other usable statistics.

-

(2)

Scrutiny of Historical Materials for 1910s–1930s in the Official Archives and Re-Examination of Statistics

Given the tragedies of the revolution, civil war, incursions by foreign powers, War-communism, and famine, it would not be odd if a marked decline in population from the end of the 1910s to the early 1920s was observed. This is indeed the case. In the last years of the imperial era and at the beginning of the Soviet era, the population dropped sharply, probably because of factors such as the large number of people who fled the country during the revolution and ensuing civil war. As far as the authors can tell from the investigations made for this chapter, there is no data at all for the period from the revolution to the first half of the 1920s.

The same can be said for the 1930s. Between 1930 and 1933, the collectivization of agriculture led to a decline in crop yields, and this resulted in famine. Yet it is widely known that crops continued to be exported from regions such as the Ukraine, despite the fact that people at home were starving (Rosefielde 1983). It has also been pointed out that the Great Purge, which reached its peak in 1936–1938, claimed several million victims (Rosefielde 1983; Wheatcroft 1984). 48 This presents the problem of whether to trust dynamic statistics that do not show anything unusual, other than the marked increase in the crude death rate between 1933 and 1934, even if these statistics have been stored in official archives not yet made public. Andreev et al. (1998) raised clear objections to this and made their own estimates. Any large change in dynamics can easily be seen years later in the distorted population pyramids they leads to, so the authors recognize the need for a re-examination.

-

(3)

Surveys of Statistics During and Immediately after World War II

World War I and World War II turned Russia into a battlefield, and it is hardly surprising that statistics are lacking for regions that were under occupation. The archived historical materials the authors found enabled one to identify the regions for which data is lacking. However, even the figures for regions for which data can be obtained are lacking in credibility. 49 Statistics for just the regions for which data for 1942–1944 can be obtained show the rate of natural increase was indeed negative, but the annual rate of decline is less than 1 %. These statistics therefore do not reflect the true population dynamics during World War II, which show up clearly in the distorted age distribution derived from the 1959 census. Further investigations and estimates are therefore required.

It would obviously be unrealistic to expect a high level of accuracy from statistics when the country was in turmoil. However, one also needs to be careful not to immediately deny the usefulness of such statistics and reject them out of hand. This is because if one demands precision, usable statistics for the early years of the Soviet Union are extremely scarce. The authors think that it is therefore better to obtain whatever statistics are available, and use them to get an idea of overall trends.

As described in this chapter, the demographic history of Russia showed extreme fluctuation. If one looks at the trends from the late imperial era to the early Soviet period, it is easy to grasp that huge turmoil caused by the Russian Revolution, Great Purges and the World War II deeply affected the dynamics of Russian demography. Data mining and processing presented in this chapter were enabled thanks to the fact that governmental archive materials became accessible after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Mining and consolidation of formerly closed data were, however, still under progress and it is still difficult to take an analytical approach at a national level.

After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russian demographics suffered from huge changes again. These have been indicated in Table 2.1 and Fig. 2.1, but more specifically, a decline in total population was observed because of a rapid decrease in fertility and an increase in mortality.

Modern demographic analysis in Russia became widely possible after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the birth of modern Russia. The background to this is, firstly, that household-level and individual-level microsurvey data became accessible and, secondly, internal and formerly closed materials from the governmental statistical organization became usable for researchers. The usable data for the demographic trends in the Soviet Union and that for modern Russia differ considerably from each other; therefore the approaches to be taken should also be different. The demographic trend at the current time is, however, a mirror of past phenomenona. Without any relation to the break or the gap in the analytical approaches taken, the trends in the past remain and affect the demographic dynamics of modern Russia.

In the remaining chapters of this book, factors behind the demographic trends in the modern Russian Federation and situations during the Soviet era are referred to as as necessary. It should be pointed out that there are phenomena observed in modern Russia that originate in the history of the Soviet regime.

References

Anderson, B. A., & Silver, B. D. (1985). Demographic analysis and population catastrophes in the USSR. Slavic Review, 44(3), 517–536.

Andreev, E. M., Darskii, L. E., & Khar’kova T. L. (1993). Naselenie sovetskogo soiuza: 1922–1991 [The population of the Soviet Union: 1922–1991]. Moscow: Nauka (in Russian).

Andreev, E. M., Darskii, L. E., & Khar’kova, T. L. (1998). Demograficheskaia istoriia Rossii: 1927–1959 [Demographic history of Russia: 1927–1959]. Moscow: Informatika (in Russian).

Clem, R. S. (1986). Research guide to the Russian and Soviet censuses. Ithaca/London: Cornell University Press.

Coale, A. J., Anderson, B. A., & Harm, E. (1979). Human fertility in Russia since the nineteenth century. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Den, V. E. (1902). Naselenie Rossii po piatoi revizii [The population of Russia in the fifth revision]. Moscow: Universitetskaia tipografiia (in Russian).

Falkus, M. E. (1972). The industrialization of Russia 1700–1914. London: Macmillan Press.

Goskomstat Rossii. (1996). Rossiiskaia gosudarstvennaia statistika 1802–1996 [Russia’s state statistics: 1802–1996]. Moscow: Izdattsentr (in Russian).

Goskomstat Rossii. (1998). Naselenie Rossii za 100 let (1897–1997) [The population of Russia for 100 years, 1897–1997]. Moscow: Goskomstat Rossii (in Russian).

Goskomstat Rossii. (2001). Rossiiskii statisticheskii ezhegodnik 2001 [Statistical yearbook of Russia 2001]. Moscow: Goskomstat Rossii (in Russian).

Gozulov, A. I., & Grigor’iants, M. G. (1969). Narodonaselenie SSSR (statisticheskoe izuchenie chislennosti, sostava i razmeshcheniia) [The population of the USSR: A statistical study of the size, composition and deployment]. Moscow: Statistika (in Russian).

Heer, D. M. (1968). The demographic transition in the Russian empire and the Soviet Union. Journal of Social History, 1(3), 193–240.

Herman, E. (1982). Forwards for the serf population in Russia: According to the 10th national census, by A. Troinitskii (originally published in 1861) (pp. iii–xxiii). Newtonville: Oriental Research Partners.

Ispov, V. A. (2001). Demograficheskie protsessy v tilovykh raionakh Rossii [Demographic processes in the rear areas of Russia]. In Iu. A. Poliakov & V. B. Zhiromskaia (Eds.), Naselenie Rossii v XX veke: istoricheskie ocherki [The population of Russia in the twentieth century: Historical sketches] (Vol. 1, Chap. 4, pp. 82–105). Moscow: ROSSPEN (in Russian).

Kabuzan, V. M. (1963). Narodonaselenie Rossii v XVIII–pervoi polovine XIX v. (po materialam revizii) [The population of Russia from the eighteenth century to the first half of the nineteenth century (based on Revizii materials)]. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo akademii nauk SSSR (in Russian).

Kabuzan, V. M. (1971). Izmeneniia v razmeshchenii naseleniia Rossii v XVIII–pervoi polovine XIX v. (po materialam revizii) [Changes in the population distribution of Russia from the eighteenth century to the first half of the nineteenth century (based on Revizii materials)]. Moscow: Nauka (in Russian).

Kluchevsky, V. O. (1918). A history of Russia (Vol. IV). (C. J. Hogarth, Trans.). 1931. London: J. M. Dent & Sons.

Koeppen, P. (1847). Unber die Vertheilung der Bewohner Russlands nach Standen in den verschiedenen Provinzen. Aus den Memoires de l’Academie Imperiale des sciences de St.-Petersbourg, VI Serie, sciences politiques etc. tome VII besonders abgedruckt, St. Petersburg, pp. 401–429.

Kumo, K. (2003). Migration and regional development in the Soviet Union and Russia: A geographical approach. Moscow: Beck Publishers Russia.

Leasure, S. W., & Lewis R. A. (1966). Population changes in Russia and the USSR: A set of comparable territorial units [Social Science monograph series, vol. 1, no. 2]. San Diego: San Diego State Collage Press.

Lorimer, F. (1946). The population of the Soviet Union: History and prospects. Geneva: League of Nations.

Matthews, M. (1993). The passport society: Controlling movement in Russia and the USSR. Oxford: Westview Press.

Ministerstvo vnutrennikh del Rossiiskoi Imperii (MVD RI). (1863). Statisticheskii tablitsy Rossiiskoi Imperii vyp. vtoroi, nalichnoe naselenie imperiia za 1858 god [Statistical tables of the Russian empire (Vol. 2), The present population of the empire in 1858]. Sankt-Peterburg (in Russian).

Ministerstvo vnutrennikh del Rossiiskoi Imperii (MVD RI). (1858). Statisticheskii tablitsy Rossiiskoi Imperii vyp. pervyi, nalichnoe naselenie imperiia za 1856 god [Statistical tables of the Russian empire (Vol. 1), The present population of the empire in 1856]. Sankt-Peterburg (in Russian).

Ministerstvo vnutrennikh del Rossiiskoi Imperii (MVD RI). (1866). Statisticheskii vremmennik Rossiiskoi Imperii tom 1 [Statistical annals of the Russian empire, Vol. 1]. Sankt-Peterburg (in Russian).

Ministerstvo vnutrennikh del Rossiiskoi Imperii (MVD RI). (1890). Statistika Rossiiskoi Imperii, XII, Dvizhenie naseleniia v evropeiskoi Rossii za 1886 g [Statistics of the Russian empire (Vol. 12), The movement of the population in European Russia in 1886]. Sankt-Peterburg (in Russian).

Otchet. (1864a). Otchet o sostoianii Iaroslavskoi gubernii za 1864 g [The report on the state of the Yaroslavl province for 1864] TsGIA (Tsentral’nyi gosudarstvennyi istoricheskii arkhiv) Fond 1281, Opis’ 7, Delo 48 (in Russian).

Otchet. (1864b). Otchet o sostoianii Sankt-peterburgskoi gubernii za 1864 g [The report on the state of the St. Petersburg province for 1864] TsGIA Fond 1281, Opis’ 7, Delo 27 (in Russian).

Podiachikh, P. G. (1961). Naselenie SSSR [The population of the USSR]. Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe izdatel’stvo politicheskoi literaturi (in Russian).

Poletaev, V. E., & Polskii, M. P. (1992). Vsesoyuznaia perepis’ naseleniia 1939 goda. Osnovnie itogi [All-union population census in 1939: Main results]. Rossiiskaia akademiia nauk, Nauchnyi sovet po istoricheskoi geografii, Institut rossiiskoi istorii, Upravlenie statistiki naseleniia Goskomstata. Moscow: Nauka (in Russian).

Poliakov, Iu. A., & Zhiromskaia, V. B. (Eds.). (2000). Naselenie Rossii v XX veke: istoricheskie ocherki [The population of Russia in the twentieth century: Historical sketches] (vols. 3). Moscow: ROSSPEN (in Russian).

Poliakov, Iu. A., & Zhiromskaia, V. B. (Eds.). (2001). Naselenie Rossii v XX veke: istoricheskie ocherki [The population of Russia in the twentieth century: Historical sketches] (vols. 3). Moscow: ROSSPEN (in Russian).

Poliakov, Iu. A., Zhiromskaia, V. B., Tiurina, E. A., & Vodarskii, Ia. E. (Eds.). (2007). Vsesoiuznaia perepis naseleniia 1937 goda: obshchie itogi. Sbornik dokumentov i meterialov [All-union population census in 1939: Overview. Collections of documents and materials]. Moscow: ROSSPEN (in Russian).

Popov, P. I. (1988). Gosudarstvennaia statistika i V. I. Lenin (The state statistics and V. I. Lenin). Vestnik statistiki (Statistical bulletin), No. 7, pp. 48–54 (in Russian).

Rashin, A. G. (1956). Naselenie Rossii za 100 let [The population of Russia for 100 years]. Moscow: Gosudarstvennoe statiskichekoe izdatel’stvo (in Russian).

Rosefielde, S. (1983). Excess mortality in the Soviet Union: A reconsideration of the demographic consequences of forced industrialization 1929–1949. Soviet Studies, 35(3), 385–409.

Shimchera, V. M. (2006). Razvitie ekonomiki Rossii za 100 let: istoricheskie riadi [The development of the Russian economy for 100 years: Historical statistics]. Moscow: Nauka (in Russian).

Sulkevich, S.I. (1940), Territoriia i naselenie SSSR (Territory and Population of the USSR), Politizdat pri TsK VKP, Moscow (in Russian).

Troinitskii, A. (1861). The serf population in Russia: According to the 10th national census (E. Herman, Trans.). Newtonville: Oriental Research Partners.

Tsentral’noe statisticheskoe upravlenie (TsSU) RSFSR. (1928). Estestvennoe dvizhenie naseleniia RSFSR za 1926 g [The natural movement of the population in the RSFSR for 1926]. Moscow: TsSU RSFSR (in Russian).

Tsentral’noe statisticheskoe upravlenie (TsSU) SSSR. (1942). Otchetnost’ statisticheskikh upravnenii soiuznykh respublik po ischisleniiu naseleniia 1941–1942 gg [Estimated population in 1941–1942: Report by the central statistical directorates of the union republics], Vol. 2, RGAE, Fond 1562, Opis’ 20, Delo 322 (in Russian).

Tsentral’noe statisticheskoe upravlenie (TsSU) SSSR. (1928a). Estestvennoe dvizhenie naseleniia Soiuza SSR 1923–1925 [The natural movement of the population in the USSR for 1923–1925]. Moscow: TsSU (in Russian).

Tsentral’noe statisticheskoe upravlenie (TsSU) SSSR. (1928b). Estestvennoe dvizhenie naseleniia Soiuza SSR v 1926 g [The natural movement of the population in the USSR for 1926]. Moscow: TsSU (in Russian).

Tsentral’noe statisticheskoe upravlenie (TsSU) SSSR. (1941). Sbornik tablitsy naseleniia SSSR po perepisi 1897 goda v granitsakh na 1 ianvaria 1941 goda [The collections of statistical tables on the 1897 population census according to the territorial boundary of the USSR on the 1st April]. RGAE, Fond 1562, Opis’ 20, Delo 190 (in Russian).

Tsentral’nyi statisticheskii komitet MVD. Ezhegodnik Rossii, 1905, …, 1911 [Yearbook of Russia in 1905, …, 1911]. Sankt-Peterburg (in Russian).

Tsentral’nyi statisticheskii komitet MVD. Statisticheskii ezhegodnik Rossii, 1912, …, 1916, 1918 [Statistical yearbook of Russia in 1912, …, 1916, 1918]. Sankt-Peterburg (in Russian).

TsUNKhU SSSR. (1937). Dannie TsUNKhU o perepisi naseleniia za 1937 god (formy NN11, 12, 12-a I 17) [1937 population census data from the central administration of national-economic records, format no.11, 12, 12–a I, 17]. RGAE (Rossiiskii gosudarstvennyi arkhiv ekonomiki), Fond 1562, Opis’ 329, Delo 144 (in Russian).

Valentei, D. I. (Ed.). (1985). Demograficheskii entsiklopedicheskii slovar’ [Demographic encyclopedic dictionary]. Moscow: Sovetskaia entsiklopediia (in Russian).

Vishnevskii, A. G. (Ed.). (2006). Demograficheskaia modernizatsiia Rossii 1900–2000 [Demographic modernization in Russia 1900–2000]. Moscow: Novoe izdatel’stvo (in Russian).

Vodarskii, Ia. E. (1973). Naselenie Rossii za 400 let (XVI-nachalo XX vv.) [The population of Russia for 400 years: Eighteenth century – the early twentieth century]. Moscow: Prosveshchenie (in Russian).

Wheatcroft, S. G. (1984). A note on Steven Rosefielde’s calculations of excess mortality in the USSR: 1929–1949. Soviet Studies, 36(2), 277–281.

Wheatcroft, S. G. (1990). More light on the scale of repression and excess mortality in the Soviet Union in the 1930s. Soviet Studies, 42(2), 355–367.

Yamaguchi, A. (2003). Foundation of Russian governmental statistical systems. Chiba: Azusa-Shuppan (in Japanese).

Zemskov, V. N. (2000). Massovye repressii: zakliuchennye (Mass repressions: Prisoners). In I. A. Poliakov & V. B. Zhiromskaia (Eds.), Naselenie Rossii v XX veke: istoricheskie ocherki [The population of Russia in the twentieth century: Historical sketches] (vol. 1, pp. 311–330). Moscow: ROSSPEN (in Russian).

Zhiromskaia, V. B. (2000). Demograficheskaia istoriia Rossii v 1930-e gody [The population of Russia in the 1930s]. Moscow: ROSSPEN (in Russian).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix: Time Series of Alternative Estimates of the Total Population of the Territory Covered by the Present Russian Federation in the Imperial Era

As said in the main text, it is possible to produce a time series for the population of European Russia that meets certain standards, with the problem being the populations of regions outside European Russia, such as the Caucasus, Siberia, and the Russia’s far east. Here the authors make alternative estimates based on the statistics for European Russia during the Imperial era.

-

(1)

The populations of each province during the imperial era can be obtained as (a) actual data only for certain years, namely 1867, 1870, 1883, 1885, 1886, 1891, and after. In addition, because data on births and deaths for each province exist for every year from 1867, it is possible to extrapolate (b) estimated populations for the other years by subtracting figures for natural increase from the populations in 1916. Furthermore, it is possible to adjust the actual data for the years mentioned above to the area of the European part of the present Russian Federation. The population of the present territory of European Russia was between 60 % and 63.5 % of the population of imperial European Russia, but the trend was for this percentage to decline. For the other years, meanwhile, only the total population (not the population of each province) of imperial European Russia could be obtained. For these total populations, the authors adopted a (c) procedure of focusing on years for which it was possible to make adjustments for area and applying, with some leeway, the ratio of the total population of the present territory of European Russia and the total population of imperial European Russia, and calculating means for years for which both total and by-province populations were available. The authors used this procedure to calculate the total population of the territory covered by modern European Russia.

-

(2)

The populations of the non-European territory of the present Russian Federation in the imperial era were obtained from (a') actual data for 1885 and 1904 and after. Although statistics do not exist for other years, it is possible to produce a (b') time series for cases where the rate of increase was exactly the same as that of imperial European Russia. The total population of this territory as a proportion of the total population of the territory of modern European Russia increased continuously from 1885, when it was 18.3 %, to 1916, when it was 26.9 %. For 1885 and earlier (c'), the authors fixed the total population of this territory as a proportion of the territory of modern European Russia at 18 %, steadily increasing this percentage for the years that followed, and then applying actual percentages once again to 1904 and after, to calculate hypothetical populations for the non-European parts of the present Russian Federation. In doing this the calculation for the base total populations of European Russia used both (b) and (c).

The above figures were then put together to present a time series for the total population of the territory covered by the present Russian Federation. The results are shown in Figure 2.A alongside the estimated (main) time series from the main text, and one can see that the two series are similar. This is because both series are based on dynamic statistics for imperial European Russia, and because during the imperial era the total population of the non-European part of the present Russian Federation as a proportion of the total population of the territory of the present Russian Federation was always less than 23 %. However, neither method accurately takes into account the population dynamics of the non-European part of the present Russian Federation. If it were possible to use time series for indicators such as grain yields, it would obviously be better to use such figures. Again, though, the problem is whether such data would be obtainable and reliable.

Notes

-

1.

As an example of the modernization that occurred during the imperial era, the volume of domestically produced steel for railways overtook the volume of imports of such steel during the late 1800s. See Falkus (1972).

-

2.

However, some say that 5 % or less of the total population was missed (Valentei 1985), and given that they provide an otherwise unavailable insight into the period from the early eighteenth century to the end of the nineteenth century, they are well worth looking at.

-

3.

Koeppen (1847) studied only the 1830s, Den (1902) only the end of the eighteenth century and beginning of the nineteenth century, and Troinitskii (1861) only the mid-nineteenth century.

-

4.

The same can be said of studies by Vodarskii (1973), Vishnevski (2006), and other researchers. Many studies rely completely on Rashin (1956) for their descriptions of the population from the late 1800s to the early 1900s. In the authors’ view, none of the research on population dynamics in this period has surpassed Rashin’s (1956) approach of constructing almost all of his data from publications by the Imperial Central Statistical Committee.

-

5.

The areas of provinces in the imperial era were calculated using maps produced by organizations such as the Imperial Geographic Society. See MVD RI (1858, 1863). The authors attempted, for the early imperial era, to use changes in regional areas to estimate changes in administrative divisions, and then use these estimates to investigate the changes in administrative divisions. However, the approach was abandoned because differences in the precision of the maps altered the numbers.

-

6.

These administrative divisions refer to economic regions (ekonomicheskie raioni).

-

7.

The biggest differences were with the vast yet sparsely populated West Siberia economic region (4.13 %, 1897), and the Southern economic region (3.22 %, 1926), which centers on modern Ukraine. The effect of the former difference is likely to be small, and the latter region is not part of the modern Russian Federation.

-

8.

Goskomstat Rossii (1998) gives the total population at the time of the 1917 revolution as 91,000,000. Even ignoring the fact that this figure is too simplistic in comparison with those of other years, it is difficult to believe that it is possible to obtain reliable population statistics for that year. The Tsentralnii statisticheskii komitet MVD (1918) describes the 1917 population figure as “preliminary.” In February 2007, when the 1917 population statistics were checked using archived historical materials from the Russian State Economic Archive RGAE, this population figure was described as the “possible population in 1917” (veroiatnaia chislennost naseleniia) (RGAE, F.1562, O.20, D.1a). On July 31, 2007 four population statisticians were interviewed on this matter at the headquarters of Russia’s Federal State Statistics Service (Rosstat) and said that the 1917 figure published in Goskomstat Rossii (1998) was an estimate, which the publication made no mention of. There is also no mention of the fact that populations for each region based on the 1937 population census were affected by personnel such as border guards and soldiers being treated differently in the statistics. In addition, the figures for the total populations of the republics in 1937 differ from those disclosed elsewhere. Although it claims that the number of soldiers etc., which were only recorded for the federation as a whole, were not just added to the estimate of the population of the Russian Republic, it does not mention that the estimation method was based on estimates. Moreover, it presents figures representing the results of the 1897 population census of imperial Russia that have been converted to match the present territory of Russia. According to these figures, the population of the territory of the present Russian Federation (excluding Kaliningrad, the Kurile Islands, and southern Sakhalin) in 1897 was 67,473,000. Among the historical materials examined at the Russian State Economic Archive was the TsSU SSSR (1941), which calculates the 1897 populations of the administrative divisions as they were in 1941 using detailed area proportions. Using these figures to calculate the total population of the territory of modern Russia gives a figure of 66,314,000, which casts doubt over the accuracy of the figure presented in Goskomstat Rossii (1998), for which the methods of calculation used are not explained at all clearly.

-

9.

The results of the 1937 population census have not been officially made public by the statistical authorities. Zhiromskaia (2000) conducted her study using archived historical materials. TsSU SSSR (1937) tells one that not only was a total population figure calculated, but that tables of data for things like occupations by educational attainment and domicile (i.e. urban or rural) were also produced.

-

10.

Ispov (2001) deals with the 1941–1945 period (i.e. World War II), but does not adjust the territories (or mention this lack of adjustment) of the Crimean Autonomous Republic (then part of Russia, now part of Ukraine) or of the Karelo-Finnish Republic (then a Soviet republic separate from Russia, now part of Russia).

-

11.

From here onwards all dates until 1917 use the Russian calendar in this chapter. The Gregorian (western) calendar is 13 days behind the Russian calendar in 20th-21st century.

-

12.

It has been posited that household-based taxation encouraged households to band together to form new households, so as to reduce the tax burden (Kluchevsky 1918).

-