Abstract

Decades after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, residential renting in the Russian Federation has come a long way from its restrictively regulated origins; and yet rental housing is still considered a residual segment of the housing market. The chapter takes a look at the uneven economic and policy development surrounding the sector; assesses the size and operation of private rental housing nationally and in the capital Moscow, where its role is particularly prominent; and analyses the sector in Russia through providing an overview of demand- and supply-side actors.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Before 1990, the Soviet government regarded private rental housing as a necessary evil that performs the useful function of mitigating housing shortage problems and supporting labour mobility. It helped the government to pretend to be adhering to its policy of restricting growth in large cities—an issue that the planned economy could never solve (Andrucz 1984). Ideological barriers, however, prevented the policy from being properly articulated and institutionalised.

After 1990 and during the first two decades of the housing market’s development, Russian governments viewed rental housing as a residual segment of housing policy. Most efforts were directed at giving away units in multi-family buildings (by privatisation of public dwellings to the ownership of tenants) and at other forms of supporting home-ownership. The private rental sector (PRS) survived the transition and increased in size, but it continued to provide only temporary housing solutions to tenants. Thus, housing policy models in both the Soviet and the post-Soviet period were dualist, and private tenancy was and still is a residual segment of it.

As a result Russia experiences a high demand for rental apartments, coinciding with a pronounced scarcity of legal rental housing supply (Rental Choice 2005). Only recently policy-makers have acknowledged the need for a paradigm shift by recognising the complementary role of rental housing. Both legalising and institutionalising informal or illegal renting and creating favourable conditions for market-based provisions of rental housing are being considered, but with limited results so far (Peppercorn and Taffin 2013). The case of the Russian Federation demonstrates how enduring the residualisation of private renting is under different economic regimes as well as its strong path dependency.

Private Rental Sector in the Soviet Period

Private rental housing in the Soviet housing system was represented by the illegal or semi-legal sector of subletting of state or co-op housing by sitting tenants and to a limited extent by the letting of individual housing in rural areas and small towns. The discrimination against private rental housing was a political hallmark of socialist ideology: private renting was considered a key mechanism of exploitation of the working class by capitalist landlords. However, pressing housing needs and labour mobility forced the government to tolerate limited private renting, officially regarding it as a vestigial form of housing tenure, being selective in enforcement of the existing legislation.

During the Soviet period it was assumed that the subtenant would pay only the expenses connected with the maintenance and repair of housing and the consumption of utilities. All extra payments were interpreted as ‘extraction of unreal income’ 1 and were illegal. Moreover, there was a legal provision by which all income from sub-rental operations in excess of payments to cover maintenance and utility expenses could be confiscated and directed into to the state budget. The collection of higher rent than was allowed by law was a legal ground for eviction of ‘landlord’ from public or cooperative housing (Housing Code 1983, art. 10, 134). As a result, the parties to a subletting contract did not draw up formal written agreements. Similar provisions were applied to the letting of housing space in individual (privately owned) housing, which was also officially permitted. 2 Unfortunately, there are no reliable data on the share of housing that was used for private letting or subletting; based on an estimate in early 1990s, it made up 5–10 per cent of the housing stock.

The semi-legal nature of landlord-tenant relations made the parties on both sides more vulnerable, and this did not encourage the development of private renting as a form of long-term housing. Tenants and subtenants did not consider private renting to be a long-term solution and were ready to be evicted at any moment; the notion of private rental housing as transitory thereby became embedded in people’s minds. The lack of detailed legislative regulation of relations in the private rental housing sector and the non-existence of professional landlords certainly influenced the development of the PRS after 1990.

The Dynamics of the PRS in 1991–2015

The transition to the market economy was marked by the mass give-away privatisation of state and municipal housing by sitting tenants ; most privatisation transfers occurred during the 1990s but they are still taking place today. As a result, the share of housing that is privately owned increased from 33 per cent in 1990 to 87 per cent in 2014, and the share of housing owned by physical persons rose from 26 per cent to 83 per cent. This radical change in the ownership structure created a new environment for the PRS development. However, the transition to a market economy did not result in the emergence of professional landlords ; one reason for this may be that during the privatisation of state-owned enterprises in the 1990s—who might become influential private landlords —the housing stock these enterprises owned was supposed to be transferred to municipal ownership. 3

Renting housing for free market rents became a legal business. Private landlords had to adhere to only a few legal requirements. First, they were responsible for paying income tax on rent revenues: since 2001, a flat income tax rate of 13 per cent was introduced and it replaced the complicated system of progressive tax rates differentiated by total income level that had been in place during the 1990s. 4 Second, landlords were responsible for paying property tax on housing properties: a local tax based on the ‘inventory value’ of a real estate object, which was in fact many times lower than the real market value of a dwelling. 5 However, the overwhelming majority of private landlords ignore the duty to pay income tax on rent revenues, and thus the dominant part of market is still in the shadow or ‘grey’ area of the economy (as is the practice of subletting housing space in state or municipal housing).

Legislative Reforms in a Sluggish Policy Environment (1991–2004)

Generally, the Soviet PRS model continued to work during this period. The change in the legal status of the transactions—from the sublettin g of public housing to the letting of private housing (in most cases acquired under public housing privatisation )—did not change the real nature of the relations between landlords and tenants. New legislation provided the basic regulation of landlord-tenant relations in the private sector (Civil Code 1996). The legislation contained 17 rather short articles that introduced only a few regulations that had to be adhered to rental contracts in both the private and public sector. 6 For public housing, rental relations were also regulated by specific housing legislation (Housing Code), which surprisingly did not apply to the PRS. 7

The Civil Code established a maximum term for rental contracts (5 years). This rigid requirement is, however, largely negated by the strongly asserted priority right of sitting tenants to renew a contract for another term; there are only a few conditions under which the landlord can refuse to prolong a rental contract. The Civil Code also contained provision for evicting a tenant: rent arrears for more than six months. 8 However, even justified eviction was possible only by judicial process and the court could give a tenant up to two additional years to avoid it. 9 The provisions of the Civil Code were biased towards protecting the rights of tenants at the expense of the rights of landlords. This did not help in the development of legal forms of landlord-tenant relations.

Housing policy during that period can be described as fragmented and as addressing only the most pressing needs of certain groups (military, young families, etc.). It gave almost no support to the development of the PRS. In contrast, certain provisions in tax legislation designed to support home-ownership had a negative effect on the development of the PRS, for example, allowing resources used to purchase housing to be deducted from income taxation by homeowners. Homebuyers can deduct from personal income taxation up to RUB 2 million (EUR 27,800) 10 spent on the purchase of housing, but no similar deduction is applied to expenditures of a tenant living in the PRS. In the mid-1990s, housing allowances for tenants in the private sector were introduced by the Russian government, but they were restricted to households headed by a military servant.

The PRS Outside the Framework of National Housing Policy (2005–2011)

In 2005 a package of housing legislation—27 acts including the new Housing Code—came into effect. That marked a new period in the development of national housing policy, but this legislative package did not lead to any additional regulation of the PRS. The increasing affordability of home-ownership was the main priority of the new policy. It was based on the assumption that economic growth, which improved the conditions for mortgage lending and increased real incomes of households, would make housing ownership affordable for the majority of households in the foreseeable future.

The new legislative framework gave impetus to housing market development and in particular to rise in housing construction and mortgage lending. Volume of new housing construction increased from 41 million m2 of housing floor area in 2004 to 64 million m2 of housing floor area in 2008. Efforts focused on supporting two new institutions that were trying to make home-ownership more affordable: the Agency for Housing Mortgage Lending and the Fund for Housing Construction Development. The amount of subsidies to homebuyers (up-front subsidies, housing certificates) dramatically increased. These changes, however, worsened the tenure-neutrality of the Russian housing regime . The public rental sector was seen as a residual one, that is, as a housing solution for only some low-income households . The role of private rental housing was not considered at all.

With new housing policies implemented, the affordability of housing really improved: the share of households that were able to purchase a standard housing unit using their own resources and a mortgage loan jumped from 9 per cent in 2005 to more than 25 per cent in 2008. 11 However, it soon became clear that there would be a limit to further increases in housing affordability, and a household with median income would not be able to buy adequate housing in the market in the foreseeable future (Fig. 12.1). Moreover, the economic recessions of 2008–2009 and the one which started in 2015 reversed the positive trends in housing affordability. These changes drove increased attention in the direction of rental housing, and private rental housing in particular, as a weak element of the Russian housing regime .

The lagging development of rental housing is the result of a number of factors. First, investment projects for the construction of rental multi-apartment buildings were not financially attractive owing to the long period of return on such investments (in particular when compared with financial attractiveness of projects for construction of housing intended for immediate sale). The market rents were relatively low and reflected the backcloth of the predominance of small landlords who paid very low price to become owners as a result of privatisation and who never had to cover the real market costs of the purchase of their dwelling. Market rents were thus not affordable for the majority of households (see below) on one side, but did not offer attractive yields for developers on the other side.

The average monthly rent for a two-room apartment in a large Russian city (other than Moscow) is RUB 15,000–20,000 (EUR 209–268). Conditions that would be acceptable to current investors (a pay-off period of no more than 10 years and ROI no less than 9 per cent) could be reached if the rent for this kind of apartment amounted to RUB 30,000–35,000 (EUR 417–487) per month. Projects for the construction of private rental apartment buildings were therefore unattractive without state subsidies . However, potential public subsidisation was inhibited by the risk attached to operating multi-unit apartment buildings for rent, such as the risk of the apartments later being sold off and of the developer capitalising the state subsidy . Non-profit housing organisations—actors that could have been supported without this risk—did not exist.

Buying properties on the secondary market was not a solution: market house prices increased faster than the price of newly built properties (Fig. 12.2). In 2008, the average price of one square metre of a dwelling on the secondary market surpassed the price of a similar dwelling on the primary market; and this remains true to the present day. This can be explained by a number of factors, including the fact that most of the primary housing market supply is located in urban outskirts as opportunities for in-fill development in central urban areas had been exhausted.

The state also did not have adequate instruments to promote the purchase of land for rental housing construction —in a shortage environment, rental housing construction projects could not compete with standard projects based on the sale of individual units during public land auctions. 12

However, the market infrastructure for the PRS developed to a certain extent in this period. First, most transactions occurred with the mediation of professional realtors who promoted effective rental agreements in written form (still kept by the parties and not officially registered). Nevertheless, a considerable share of such transactions (in Moscow an estimated 25 per cent) is still engaged in through the mediation of companies not registered with professional associations, ‘black realtors’, and ‘information agencies’ that are not responsible for the quality of services. Second, there began to be PRS stock that was owned by legal subjects. 13 Presumably this housing segment is mostly being developed by big enterprises, such as Gazprom or Russia Railways, and used to provide housing to their employees.

The Search for the Right Models (2012 to the Present Day)

The year 2012 marked a radical change in national housing policies related to rental housing development. The goal of establishing an effective, affordable, and professional rental market was laid out in Presidential Decree No. 600 setting the priorities for the 2012–2018 electoral cycle and in subsequent RF Government resolutions. With the goal of strengthening the coordination between state authorities, local governments, and state development institutions, the government adopted the State Programme ‘Provision of Affordable and Comfortable Housing and Utility Services to Citizens of the Russian Federation’ (State Programme 2012). The programme sets six priorities of housing policy , one of which is ‘developing an affordable rental housing market and non-profit housing stock for households with moderate incomes’. While this goal does not specify the role PRS is to play in this, it envisions the development of both public (different from existing state and municipal social housing) and private rental housing.

The new priorities of the national housing policy required an amendment to the national legislation: in 2014, the Act on Regulating Rental Housing Relations was passed (Federal Law 2014). Its main objective was to create a legal environment conducive to the development of professional private renting operating in both the commercial and social housing sectors. The principal provisions of the Act are as follows:

-

1.

It introduced the legal concept of a rental building. All the premises in such a building should be owned by one legal/physical person, rented to tenants, and the selling of individual units is prohibited or, more precisely, allowed only after the rental building status is lifted. There are two types of rental buildings: buildings used for commercial renting and buildings used for social (non-profit) renting. Social rental buildings could be in either public or private ownership; in the latter case a private owner must meet special requirements stipulated in the Act.

-

2.

It introduced the regulation of rental contracts in social rental buildings. These contracts are regulated differently than traditional social rental contracts in state or municipal social housing. The contract has a fixed term up to 10 years, the rent is supposed to cover all expenses of the landlord related to the housing unit’s construction and management, and tenants have more limited rights compared to traditional social tenants. According to the Act, at least half of all units in the building should be provided under a social rental contract if the building is to be defined as a social rental building; the rest of the dwellings can be rented out commercially.

-

3.

It established the requirement that rental contracts be registered with the authorities if they are for a term of more than one year and established a penalty for violation of this requirement.

-

4.

It introduced a special preferential regime for allocating state or municipal land for the construction of rental buildings. Public authorities will firstly determine the target use of the land (i.e. for the construction of commercial or social rental building) and auction the right to sign the agreement with investor on a particular type of building. The land itself is then transferred without tendering procedures to the winner of the auction. This prevents developers of housing for sale from trying to purchase the auctioned plots.

The new legislation introduced provisions for establishing a professional rental sector. Public authorities can now determine the target use of a plot of land as intended for rental building construction and enter into an agreement with public or private developers; the latter opens space for public-private partnership projects. Private developers get also access to long-term finance allowing them to set rents at a level competitive with the rents of non-professional landlords. Notably, the state-owned Agency for Housing Mortgage Lending has launched its new ‘Rental Housing’ mortgage product for developers or owners of rental buildings. The product grants access to long-term (up to 30 years) finance to professional landlords who own at least five flats in a rental building and sets certain standards that the borrower needs to meet. Borrowers tend to be agencies established by local public authorities (or state enterprises or joint stock companies (JSC)) but also include professional private developers, such as Asia Concrete Ltd or Russian Milk Company Ltd.

However, the transformation of the existing PRS and its non-professional landlords segment has remained outside the national agenda. Attempts have been made by several regions to increase the transparency of the current PRS with its non-professional landlords but with limited success. For example, there was an attempt in Moscow to locate potential landlords and work with them on an individual basis in 2012/2013. Inspections conducted by homeowners’ associations and local police found nearly 180,000 potential private tenancies, about 40 per cent of the estimated number of all private tenancies in the city. However, further bureaucratic procedures failed: only a minority of cases were proved and documented and, as a result, only 1 per cent of the tenancies identified were brought to the attention of the tax authorities. Consequently, the estimated share of individual landlords who have been exposed to the tax authorities is as yet no more than 4 per cent of all landlords-physical persons in Moscow.

Landlords can register under one of the alternative tax regimes. They can either pay the flat 13 per cent personal income tax, which is viewed as very complicated and time-consuming, or choose a simplified tax for individual entrepreneurs and self-employed. The latter can be applied in two ways: (1) a gross flat rate of 6 per cent without any deductions or (2) a net rate of 15 per cent applied after making deductions. The simplified regime requires the landlord to register as an individual entrepreneur and submit quarterly income statements. However, no regime allows deductions for capital depreciation or has provisions for loss carry-forward.

Additionally, the City of Moscow introduced a license (charter) that can be purchased by individual landlords. Purchasing the license replaces the obligation to pay income tax on income from rental operations, as surveys reveal that a number of landlords avoid paying income tax because of the complicated income declaration process. The price of a license is 6 per cent of imputed income from rental activities, compared to the 13 per cent flat income tax rate. However, the level of imputed annual income set by the local authorities in Moscow—RUB 1 million (EUR 13,908) annually—means the license option can only appeal to landlords at the business and elite segments of Moscow’s PRS. According to data of the territorial Federal Tax Service in the City of Moscow, the number of declarations of payment of the tax on the rental income submitted up to 1 July 2013 was 14,234 and the sum of paid tax was RUB 494.5 million (EUR 6.88 million).

A ‘Snapshot’ Analysis of the Current Status of the PRS

The Volume and Structure of the PRS Nationally and in the City of Moscow

The rental sector of the Russian Federation now includes the following segments:

-

1.

Social housing operating under a social rental contract. This segment is part of the state and municipal housing stock (inherited from the Soviet period). Tenants of these dwellings have not acquired ownership of them through privatisation but still have the legal right to do so. Some dwellings are sublet by sitting tenants to other households, so it holds also features of PRS. In 2013, this segment accounted for 11 per cent of the total housing stock (state housing—3.4 per cent, municipal housing—7.7 per cent). This segment is decreasing in size over time due to continuing privatisation .

-

2.

Specialised social housing. Specialised social housing is similar to social housing but operates under an accommodation rental contract (this housing includes dormitories or tied accommodation); it too is part of the public housing stock. In contrast to contracts in social rental housing , contracts in this housing are for a fixed term. The sector makes up 1.5 per cent of the total housing stock.

-

3.

Public renting. At least 0.2 per cent of the total housing stock is provided by state and local governments on non-commercial terms. The level of rent under such contracts is about two times higher than the rent under social rental contracts, but it is still 3–4 times lower than market rates.

-

4.

Individual PRS (housing owned by citizens and used for renting). This segment is part of the shadow economy, as it lies almost entirely outside income taxation. It is thus difficult to estimate the size of the sector. According to 2002 census data, it accounted for at least 3.3 per cent of all housing stock. Data from a survey of the population’s living conditions conducted by Rosstat in 2011 revealed that 18 per cent of Russian households own another dwelling in addition to the one they occupy; and more than half of these dwellings are suitable for use as residences. According to an expert assessment, this segment in reality accounts for 8–10 per cent of the total housing stock (Peppercorn and Taffin 2013: 120). 14

-

5.

The professional PRS operated by legal subjects (commercial entities). This housing is owned by large businesses and organisations and is intended especially to house their employees. The rental contracts are similar to commercial rental contracts or dormitory rental contracts in state or municipal housing . This segment accounts for 3.2 per cent of the total housing stock.

-

6.

Quasi-PRS includes non-residential housing that is used for long-term habitation (lofts, apart-hotels, etc.), which resemble private rental operations. These premises are formally not residential, so they do not need to be registered. According to the estimates of experts, the total stock of room and loft ‘suites’ that make up this segment accounts for about 0.02 per cent of the total housing stock.

Rental housing thus forms 26 per cent of the total housing stock (10 per cent of dwellings are rented out by individual ‘non-professional’ landlords, 12.8 per cent by the state and the municipalities, and 3.2 per cent by private legal entities). The PRS accounts probably for 13 per cent of the total housing stock or 50 per cent of the total rental housing stock.

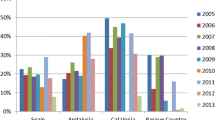

The structure of the private rental housing sector can be analysed using the example of Moscow, on which the most analytical information is available. According to the Rosstat data, the aggregate floor space of housing in the city of Moscow is 235 million m2 (as of the end of 2014). There are a total of 5 million occupied housing units, including 3.2 million units that are privately owned. Based on figures provided by experts, 15 the total volume of PRS in Moscow can be estimated at around 400,000 housing units. One-room (44 per cent) and two-room (40 per cent) flats dominate in the PRS; three-room (14 per cent) and multi-room (2.3 per cent) flats are less common. The structure of the supply of PRS housing has shifted towards smaller units than the average size in the total housing stock (Fig. 12.3). 16

The structure of supply and demand for private rental housing in Moscow (in per cent from total demand and total supply, December 2015). Source: Analytic Report of MIEL Real Estate Company—http://arenda.miel.ru/press-center/analytics/7118/

According to the classification used by Sternik’s Consulting, the private rental housing market is divided either into two classes (mass lodging and prestigious lodgings) or into four sub-classes (economy, comfort, business, and elite). Rents in one-room economy-class flats can be up to RUB 35,000 (EUR 487), in comfort-class flats they are RUB 35,000–90,000 (EUR 487–1250), in business-class flats RUB 90,000–180,000 (EUR 1250–2500), and in elite-class flats they are more than RUB 180,000 (more than EUR 2500). The database of MIEL Rest Estate Company showed that the largest share of flats (95 per cent of the housing units) is in the economy and comfort classes, and only a small portion (3.6 per cent) is in the business class, while an insignificant portion is in the elite class. However, in terms of revenues from rental income, the business class produces 10 per cent of total rental income and elite class 7.4 per cent of total rental income.

Demand and Supply of PRS

Landlords are (1) people with low income (mainly pensioners, lone mothers, marginalised persons, etc.) who let rooms in flats in which they also continue to reside (in the bottom end of the economy class); (2) people who are living or traveling long term elsewhere (comfort and business class); (3) people who for various reasons are the owners of a second flat (e.g. left vacant after the parents’ death, or after moving into the residence of a spouse or partner; these dwellings can be in any segment from economy to business class); and (3) buy-to-let investors, who purchase one, two, or more flats to rent them out (comfort and business class). These investments are often seen as inflation and pension hedges and are expected to yield medium-term capital gains.

Tenants can be grouped into the following categories: (1) temporary migrants and middle-income students demanding standard economy-class housing; (2) migrants who save up to buy a flat and who also demand economy class; (3) business people and officials who are on business trips most of the time and need a place for temporary residence (they search for business class); (4) staff of foreign firms and high-paid staff of domestic companies who rent elite-class accommodation paid for by their employer; (5) creative and sports organisations who invite guest performers on long-term contracts (they demand comfort and business class); and (6) households that do not live in their own housing for various reasons (young families, a person recently divorced, single children of well-off parents, middle-aged and elderly households living in the rented accommodations of worse quality while at the same time letting more spacious and expensive accommodation of their own, etc.) and demand premises in economy and comfort class.

The Russian PRS has often been described as a landlord’s market (Peppercorn and Taffin 2013), 17 but this is no longer the case due to the economic recession. For instance, in late 2015 the supply of rental flats in Moscow was more 1.7 time the demand. The average rent level grew until the end of 2014 and then the trend reversed (Fig. 12.4). The average term of a rental contract (90–95 per cent of all rental contracts) is one or two years. Seasonal (short-term) rentals comprise 5–10 per cent of rental contracts.

The trend in average rent levels of economy-class flats in Moscow (thousand RUB). Source: Analytic Report of MIEL Real Estate Company—http://arenda.miel.ru/press-center/analytics/7118/

At the current level of housing prices, the actual annual yield from renting an economy-class two-room flat varies from 4.3 per cent in Moscow to 6.9 per cent in Chelyabinsk (Table 12.1), 18 which is, however, below the bank deposit rate (for a one-year deposit equal to 10.3 per cent). 19 After paying the personal income tax on income from rental operations, the annual yield would decrease to 3.7 per cent (Moscow) and 6 per cent (Volgograd). The biggest buy-to-let market in Moscow has the lowest yield level. Under such circumstances corporate investors are not attracted to buy newly built buildings from developers, who are only able to sell units to individual investors, who then rent them informally and skip paying taxes.

Here only the affordability of the PRS in Moscow is measured as average data for the whole country are not available. The simulations indicate (Table 12.2) that the rent-to-income ratio calculated for a standard housing unit with floor space of 54 m2 slightly decreased during the transition but still remains high.

Landlord-Tenant Relations

As noted above, most rental contracts are nowadays concluded in writing, but the document is made public only if a dispute arises between the parties. Formal rental contracts often include clauses on penalties for rental arrears , but it is not clear how penalties are enforced in practice. The quality of formal contacts varies: most of them cover all important aspects of landlord-tenant relations, but some contracts do not contain provisions that adequately protect the rights and interests of the contract parties. Typical examples of inadequate legislative control that can cause problems in landlord-tenant relations include:

-

1.

Letting already rented housing. There are reported cases of citizens renting a flat in a low price category and then offering it for rent to another tenant. A person rents a flat at a submarket price and then sublets it to someone else, from whom he or she demands prepayment or collateral in an amount that covers all expenses for the first month and a profit on top. But when the tenant moves in, he or she encounters other tenants who have also paid rent in advance to the supposed ‘owner’ of the flat.

-

2.

The failure of the landlord to return the deposit to the tenant at the end of the tenancy despite the absence of any damage.

-

3.

The landlord raises the rent just after the tenant has incurred substantial costs in connection with moving into the apartment.

-

4.

Landlords over-control the use of the flat; some landlords believe they have the right to visit the flat at any time.

-

5.

The landlord imposes limits on the tenant’s use of wire telephone communication and internet. Some landlords block international and long-distance telephone communication.

In general, imperfections in the legislation and in the private rental market itself contribute to the spread of negative practices that increase the expenses and risk s of both private landlords and tenants, including the risk of opportunistic behaviour by both parties to the agreement, and they also create additional expenses connected with dispute resolutions of issues that could have been regulated by legislation or the contract.

The Future Prospects of the PRS

Economically, the future prospects of the development of the PRS largely depend on the attractiveness of the new legislative environment to private developers of rental buildings and on the interest of big employers in a mobile workforce. From a public policy perspective much would depend on whether additional measures of state support, in particular tax preferences, will be introduced and to what extent public authorities will be interested in PPP projects on rental sector development.

The chapter demonstrates that the PRS in Russia is rather weak and does not serve as a sustainable housing solution for potential tenants. At the same time the demand for an effective rental sector is high and increasing especially in big cities and areas of intensive economic development (new industrial clusters). Rental sector development is seen as a key factor in increasing labour mobility in the country, which is currently quite limited, with primarily only temporary or seasonal job migration. Furthermore, some policy-makers acknowledge that private rental housing may well be a cheaper alternative to the heavily subsidised new construction of social housing.

An overview of the literature on housing and urban planning policies in developed countries (Hoekstra 2003) reveals that there are three different types (archetypes) of housing policy : a liberal model (USA, Great Britain), a social-democratic model (Sweden, Netherlands), and a corporatist model (Germany, Austria). The basic archetype models reflect cultural differences between individual societies and also different concepts of the role that the state, family, various corporations, and public associations should play in housing provision. The role that the PRS will eventually play in Russia will depend on which model the country ends up following. Currently, Russian housing policy is characterised by the co-existence of elements of all three models, which is not a public choice but is rather the random coincidence of different policies (Kosareva et al. 2015).

The enduring economic recession in Russia means that the ambitious targets of rental building development set by the State Programme will probably not be met in the near future; 20 there are still just a modest number of rental building projects. The share of newly built commercial and social rental buildings formed only 0.7 per cent of all newly built multi-apartment buildings in 2014, far below the expected program targets. 21 This means that in the visible future the PRS will be still dominated by non-professional individual landlords. The priorities for developing this segment of housing could focus on stimulating conscientious behaviour on the part of both landlords and tenants and on making formal legal contracts more appealing to both sides by introducing better legislation regulating tenant-landlord relations and strengthening the enforcement of the law.

Such regulatory changes should include setting up a tenure-neutral tax regime, simplifying taxation, and encouraging use of the license model. 22 Experience has shown that administrative measures alone will not make a significant difference and could even lead to more rental activities moving into the shadow economy. Moreover, in the short term, decreasing tax rates on rental income coupled with other proposed measures might actually have the effect of increasing, not decreasing, tax revenue collection. The fact that a considerable number of landlords are pensioners, including some who live alone and for whom renting dwelling units is a considerable source of income, makes the issue of taxation enforcement sensitive. Introducing specific tax deductions for different types of landlords could also help (e.g. those who are letting only one housing unit or certain vulnerable categories of landlords). Such deductions should only be open to landlords after registering the rental contract with the state authorities and on proof of payment of income tax. Consideration should be given to introducing a tenure-neutral tax regime and possibly allowing not just people who buy housing but also tenants to take advantage of tax deductions. Similarly, the number of categories of households eligible to receive rent allowances in the PRS should be reconsidered. From a societal point of view, it is important that public recognition be made of the important social function that individual landlords perform.

Legal rental contracts should be made more attractive by improving regulatory provisions in federal legislation that govern landlord-tenant relations and by promoting effective rental contract models. An important issue that needs to be addressed in regulation is the how and under what conditions rental contracts can be terminated early by either party to the contract. As demonstrated above, the way this is currently regulated under the Civil Code is unfavourable to landlords and does not encourage them to draw up formal contracts in writing. Another important area that needs to be further addressed is dispute resolution procedures. These procedures should be designed to be fast and effective at resolving disputes and reducing the burden these procedures place on the judicial system. It would be possible to include in rental contract provisions the option that in the case of a dispute the parties turn to mediation or arbitration, 23 where the arguments of the contract parties can be examined.

Notes

-

1.

Income not earned through employment, that is, ‘unearned income’.

-

2.

A decree from 1963 set the maximum monthly rent at 16 kopecks per square metre of usable housing space.

-

3.

These dwellings could also be privatised either before or after the transfer to municipal ownership.

-

4.

Recent legislative amendments to rental contract registration and alternative taxation models are described below.

-

5.

Local governments could set tax rates in the range 0.1–2.0 per cent of the inventory value depending on the magnitude of the inventory value. Since 2015 amendments were made to the tax code setting the cadastral value instead of inventory value of a dwelling, which is supposed to be close to the market value of the housing property. The basic tax rate is set at 0.1 per cent; the legislation also establishes an untaxable minimum housing space and benefits certain categories of households. However, this legislative amendment has not yet affected the PRS. During the economic recession the assessed cadastral values in many cases appeared to be higher than the current market ones, which fuelled numerous complaints from landlords.

-

6.

The written form of rental agreement (art. 674), the transfer of a landlord’s obligations after the transfer of ownership (art. 675), the right to sublet the housing premises (art. 680) and restrictions on the reconstruction of a housing unit by a tenant (art. 678).

-

7.

Until 2014, when amendments were made to the Housing Code.

-

8.

Damage to real estate property blamed on a tenant could be also a ground for eviction .

-

9.

Up to 1 year in order to fix the damage or pay back the debt, and if the tenant fails to meet to do either of these things up to 1 year to hold on the decision on eviction .

-

10.

Hereinafter based on the Central Bank of Russia exchange rate as of 19 August 2016: 1 EUR = 71.9 RUB.

-

11.

This indicator, ‘The proportion of households who can afford to buy a dwelling, conforming to floor space per capita standards, with their own and borrowed funds’, reflects the share of households whose income is sufficient for them to be able to make monthly mortgage payments, based on an assumed down payment of 30 per cent of the property’s value.

-

12.

This is also a problem for housing supply at the moderate price segment of the purchase market .

-

13.

Some former departmental housing that was divested during the privatisation of state enterprises did not have a clear status under the law, and its status was disputed during the 1990s and early 2000s. By end of that time most legal issues were solved.

-

14.

The assessment was supported by the author’s interviews with real-estate market professionals.

-

15.

I. Peppercorn and C. Taffin note that ‘anecdotal evidence suggests that in Moscow some 17 per cent of dwellings are tenant-occupied’. The estimate here is more conservative: less than 15 per cent.

-

16.

According to 2010 census, one-room flats comprise 31 per cent of the total Moscow housing stock, two-room flats 39 per cent, and three-room flats 23 per cent.

-

17.

I. Peppercorn and C. Taffin estimated the demand for rental dwellings in Russia as three times higher than the supply.

-

18.

Annual yields on one-room flats would be a bit higher, reaching 8 per cent in Novosibirsk.

-

19.

The average for Russian banks; data from—http://www.cbr.ru/statistics/b_sector/deposits_15.xlsx

-

20.

Tax preferences are not likely to be introduced in the current economic situation.

-

21.

The specific targets were set by the State Programme: the share of newly built rental housing should be 2.0 per cent by 2014, 3.8 per cent by 2015, and 9.4 per cent by 2020 of all new housing construction in multi-family apartment blocks.

-

22.

The terms of the license system of taxation should be adjusted to make it attractive to the majority of individual landlords.

-

23.

The practice of actors in the real-estate market establishing such arbitration tribunals already exists.

References

Andrucz, G. D. (1984). Housing and urban development in the USSR (pp. 103–110). Albany: SUNY Press.

Belkina, T. (1993). Housing statistics in the housing sector. Voprosy Ekonomiki, 7, 62 (in Russian).

Civil Code of the Russian Federation. (1996). Part II as of 26 January 1996 No.14-FZ. Chapter 35.

Federal Law as of 21 July 2014, No. 217-FZ. On amendments to Housing Code of the Russian Federation and particular legal acts of the Russian Federation concerning legal regulation of rental relations in the housing stock of social use.

Hoekstra, J. (2003). Housing and the welfare state in the Netherlands: An application of Esping-Andersen’s typology. Housing, Theory and Society, 20(2), 58–71.

Housing Code of RSFSR as of 1983.

Kosareva, N., Polidi, T., & Puzanov, A. (2015). Housing policy and economy in Russia: Outcomes and development strategy (in Russian). Moscow: NRU HSE.

Peppercorn, I. G., & Taffin, C. (2013). Rental housing. Lessons from international experience and policies for emerging markets. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

State Program. (2012). ‘Provision of affordable and comfortable housing and utility services to citizens of the Russian Federation’ for the period till 2020. Adopted by the RF Government Resolution as of November 30, 2012, p. 2227.

The World Bank. (2005). Rental choice and housing policy realignment in transition: Post-privatization challenges in the Europe and Central Asia region. Infrastructure Department, Europe and Central Asia Region (ECA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Puzanov, A. (2018). Russia: A Long Road to Institutionalisation. In: Hegedüs, J., Lux, M., Horváth, V. (eds) Private Rental Housing in Transition Countries. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-50710-5_12

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-50710-5_12

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN: 978-1-137-50709-9

Online ISBN: 978-1-137-50710-5

eBook Packages: Social SciencesSocial Sciences (R0)