Abstract

Price discrimination requires sufficient separability of customers, sufficiently high costs of arbitrage and sufficient market power. It involves transferability of the good and/or transferability of demand. It can be categorized as first degree (or perfect), second degree (or self-selection), or third degree (multimarket). Its impact on consumer surplus is ambiguous.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

A supplier practises price discrimination if it charges different prices for different units of essentially the same good, with essentially the same marginal cost of supply, to either the same customer or to different customers.

Successful price discrimination requires the following:

The seller must be able to sufficiently separate customers (e.g., discounts for students or seniors).

The seller must be able to prevent resale, or at least make resale very costly, across segments (e.g., textbooks or pharmaceutical drugs are sold at very different prices in different countries, even when the suppliers have no redistribution intentions).

The seller must have some amount of market power.

Essentially, two types of arbitrage can defeat price discrimination. One type involves transferability of the good from the low-paying to the high-paying consumer – in such a case, only one kind of customer pays the fixed component of a possible two-part tariff. Typically, transaction costs provide limits on the level of such arbitrage that is possible – medical treatment, travel and utilities provide examples where such transaction costs are quite high.

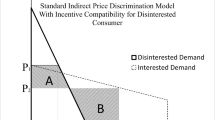

The second such type of arbitrage involves transferability of demand, where the producer uses self-selection devices to match a type of customer to the price.

To prevent arbitrage involving transferability of the good, the supplier tries to reduce the spectrum; to prevent arbitrage involving transferability of demand, the supplier tries to enhance the spectrum. As an example of the latter, consider the oft-quoted example from Dupuit (1849), quoted in Tirole (2000: 150):

It is not because of the few thousand francs which would have to be spent to put a roof over the third-class carriages or to upholster the third-class seats that some company or other has open carriages with wooden benches … What the company is trying to do is prevent the passengers who can pay the second-class fare from traveling third-class; it hits the poor, not because it wants to hurt them, but to frighten the rich … And it is again for the same reason that the companies, having proved almost cruel to third-class passengers and mean to second-class ones, become lavish in dealing with first-class passengers. Having refused the poor what is necessary, they give the rich what is superfluous.

First-Degree (or Perfect) Price Discrimination

Each customer is charged the maximum willingness and ability to pay for every unit of the good; as a result, the entire consumer surplus is appropriated by the supplier. However, it is possible that some segments that were not served under uniform pricing can be served under price discrimination.

Second-Degree (or Self-Selection) Price Discrimination

The supplier uses consumer behaviour to ‘self-select’ consumers into appropriate market segments. Examples include volume discounts that self-select consumers into less elastic (e.g., single individual) and more elastic (e.g., family) segments.

Firms also offer different peak and off-peak prices on mobile telephony, for instance, with the intention of self-selecting calls into business (less elastic) and pleasure (more elastic) categories – the critical point here is that, for most instances, the marginal cost of a peak call is about the same as that of an off-peak call.

Airlines (and some train companies) offer different prices for business and economy classes. Within these classes, discounts are offered for non-refundable tickets, Saturday-night stays or advanced purchase. The objective of this differential pricing is to self-select travel into less-elastic (e.g., business) and more-elastic (e.g., vacation) categories – for example, a business traveller will be reluctant to stay a Saturday night at the destination and will want flexibility. Despite the extra frills of business class, the marginal cost of an additional business class passenger is not very different from that of an additional economy class passenger, especially as a proportion of the fixed costs involved. And the marginal cost of an additional passenger is nearly identical for the different categories within each class.

Firms often offer different prices to current customers versus switching customers for essentially the same reasons.

Third-Degree (or Multimarket) Price Discrimination

The supplier uses observable signals related to a consumer’s demand and charges prices based on these signals. Examples include student/senior discounts at cinemas. Students and seniors typically have a more elastic demand, and the status is verifiable.

It is a perception that women have a less elastic demand for dry-cleaning than men; as a result, women pay more for essentially the same dry-cleaning services. Women’s clothes are usually distinguishable from men’s clothes, so preventing arbitrage between the customer segments is not difficult.

It is well documented that candidates who visit a college campus prior to admissions decisions have a less elastic demand for that particular institution. Such visits are typically coordinated through the college, so the college knows which candidates have visited. Similarly, a student from a poorer background is likely to have a more elastic demand for education at a college. It is more difficult to separate out the economic categories, given the incentives to under-report a family’s economic circumstances. However, it is not the case that a candidate can arbitrage a college aid package with another candidate – transferability of the good is not a factor here. These reasons explain, to an extent, the differentials in financial aid packages offered to candidates, over and above the merit-based differentials.

Academic journals typically have a sliding scale for subscriptions (e.g., a low rate for students, a higher rate for academics and a still higher rate for libraries). Some journals also have different rates depending on the country of the subscriber, even though there might not be redistribution issues. These differentials are because these segments have different elasticities of demand for journal subscriptions. Coca-Cola’s ‘smart’ vending machines, which charge different prices depending on outside temperatures, fall into this category as well.

Marginal revenue equals marginal cost holds for each market segment, and the inverse elasticity rule holds for each market segment; that is, for each segment i (price in segment i − marginal cost)/(price in segment i) = −1/(own-price elasticity of demand in segment i). In other words, the supplier should charge more in market segments with less elastic demand.

Price discrimination reduces welfare if it does not increase total output. If the total output was to remain the same or decrease under price discrimination, the marginal rate of substitution would differ across customers and, therefore, there would be lower welfare under price discrimination than under uniform monopoly pricing. In other words, for price discrimination to be welfare-increasing, it is a necessary condition that total output be higher under price discrimination.

For the special case of linear demand functions, if we were to impose the additional condition that all markets would be served under price discrimination, then welfare would be lower under price discrimination. In the absence of the additional condition of all markets being served under price discrimination, it is easy to visualize scenarios where price discrimination would lead to a Pareto improvement. The welfare effects of price discrimination are, therefore, ambiguous.

The Robinson–Patman Act in the United States, though rarely used currently against price discrimination, applies to price discrimination and injury to competition in sales of commodities of like grade and quality in commerce. Such price discrimination can be legally justified through cost differentials or through meeting a competitor’s price.

References

Tirole, J. 2000. The theory of industrial organization. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Further Reading

Besanko, D., D. Dranove, M. Shanley, and S. Schaefer. 2010. Economics of strategy. Hoboken: Wiley.

Devinney, T. (ed.). 1988. Issues in pricing. Lexington: Lexington Books.

Dolan, R., and H. Simon. 1996. Power pricing. New York: Free Press.

Gellhorn, E. 1986. Antitrust law and economics. St Paul: West Publishing Company.

Nagle, T., and R. Holden. 2002. The strategy and tactics of pricing. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Copyright information

© 2018 The Author(s)

About this entry

Cite this entry

Bhattacharya, R. (2018). Price Discrimination. In: Augier, M., Teece, D.J. (eds) The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Strategic Management. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-00772-8_674

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-00772-8_674

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN: 978-0-230-53721-7

Online ISBN: 978-1-137-00772-8

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementReference Module Humanities and Social SciencesReference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences