Abstract

This entry provides an overview of dominant logic and discusses recent research developments. Cognitive, behavioural and hybrid approaches to studying dominant logic are discussed. Particular attention is given to the emergence of dominant logic and its effects on strategic action and performance. Finally, we provide suggestions for future research.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download reference work entry PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Dominant (general management) logic has been defined as ‘the way in which managers conceptualize the business and make critical resource allocation decisions – be it in technology, product development, distribution, advertisement or in human resource management’ (Prahalad and Bettis 1986: 490) and, following from this an ‘information filter’ (Bettis and Prahalad 1995: 7) that defines what is and is not important for managerial attention.

Dominant (general management) logic has been defined as ‘the way in which managers conceptualize the business and make critical resource allocation decisions – be it in technology, product development, distribution, advertisement or in human resource management’ (Prahalad and Bettis 1986: 490) and, following from this, an ‘information filter’ (Bettis and Prahalad 1995: 7) that defines what is and is not important for managerial attention. Dominant logic was introduced into the literature to explain the relationship between diversification and performance (Prahalad and Bettis 1986). However, dominant logic has seen a much broader application in the subsequent literature and has been used to explain a wide variety of strategy actions and outcomes such as acquisitions (Coté et al. 1999), joint venture success (Lampel and Shamsie 2000), corporate strategy (Ray and Chittoor 2005), strategic change (Von Krogh et al. 2000; Jarzabkowski 2001), knowledge management processes (Brännback and Wiklund 2001) and firm performance (Obloj and Pratt 2005; Obloj et al. 2010).

Dominant logic is one specific form of a model in an organization – a largely mental model of strategy shared by the top management team. One other class of models is what are commonly referred to as business models (Baden-Fuller and Morgan 2010; Teece 2010). Business models are often more explicit and codified than dominant logic and are directly related to value propositions. Another strategy model is the kernel of a strategy (Rumelt 2011), which encapsulates the core content of a strategy.

Over time, the underlying epistemological assumptions of dominant logic have evolved (Von Krogh and Ross 1996). Furthermore, the positive effects of dominant logic as a filter has been contrasted with the more negative effects of dominant logic as a blinder (Prahalad 2004; Bettis et al. 2011).

Operationalization of Dominant Logic

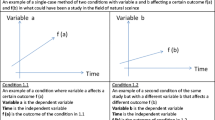

Given the theoretical breadth and richness, the operationalization of dominant logic has been challenging. Some empirical studies on dominant logic emphasize the behavioural aspects of dominant logic. For instance, D’Aveni et al. (2004) associate a congruence of resource allocation among lines of business with efficiency and profitability. Others focus more on the cognitive properties of dominant logic. Ginsberg (1989) sees dominant logic as a mental map and measures it based on two properties: cognitive complexity and cognitive differentiation. Finally, some operationalize dominant logic as a hybrid construct combining cognitive and behavioural aspects. Coté et al. (1999) measure dominant logic using three dimensions: (1) conceptualization of the role of the firm and acquisitions; (2) criteria for choice and evaluation; (3) organizing and management principles. They argued that the consistency among these three dimensions of dominant logic is related to success in acquisitions.

Von Krogh et al. (2000), by contrast, operationalized dominant logic along six dimensions that refer to the internal and external environment (people, culture, product, competitors, customers and technology) and related the breadth of dominant logic to the effectiveness of change. Obloj et al. (2010) take the stance that dominant logic is a system of four elements and found that a high performing dominant logic is related to external opportunity-seeking orientation, proactiveness, organizational learning and (low) codification of routines. These different ways of operationalizing show a clear trend towards multidimensional operationalization. The criteria for a successful dominant logic are related to a particular orientation in the individual dimensions of dominant logic. Even more frequently in more recent research, the success criteria are related to the coherence or consistency between dimensions.

Emergence of Dominant Logic

Given that dominant logic was originally focused on large firms, most empirical studies have focused on studying large, established organizations. However, in such a context, the dominant logic elements become internalized in systems, structure and processes, and are hence no longer directly accessible. Cause-effect relationships are further obstructed by the complexity of large organizations.

Recently, articles have started to explore the emergence of dominant logic in ventures. For instance, Porac et al. (2002) studied dominant logic in software ventures and Obloj et al. (2010) examined the emergence of dominant logic in ventures in a transition economy. The context of entrepreneurial ventures is particularly interesting because it allows how organizations developmental models – how a dominant logic emerges – to be studied.

Different elements of dominant logic develop and increasingly cohere or hang together. In this way the process of establishing coherence among the different elements of a firm’s dominant logic affects the effectiveness of dominant logic later in the organization’s lifecycle. In other words, the emergence of dominant logic is decisive for how well the organization will be able to adapt to changes in the environment. Coherence among the element constituting a dominant logic constitutes a fine line: while coherence is associated with superior performance (e.g., Hamel and Prahalad 1994; Black et al. 2005), too much coherence can be associated with limiting strategic change.

Implications for Future Research

A focus on the emergence of dominant logic requires studying the relevant processes to understand the patterns through which it develops. Of particular interest is the study of entrepreneurial ventures and firms in less well-established industries (e.g., Santos and Eisenhardt 2009) and firms that are active in a transition economy (e.g., Obloj et al. 2010), because, in these situations, researchers can witness how coherence among the different dimensions of dominant logic comes about. Social and environmental ventures can also be a very interesting field of study for dominant logic.

Other methods are used to study dominant logic. Examples for such methods are repertory grid technique (Wright 2008) and causal mapping (Jenkins and Johnson 1997; Nadkarni and Narayanan 2005, 2007). Particularly interesting could also be the use of experiments where participants perform a search on a rugged landscape model (e.g., Billinger et al. 2013) or in a business simulation game (e.g., Gary and Wood 2011; Gary et al. 2012).

On a theoretical level, we see several areas of special interest. First, political processes most definitely influence the organizational dynamics and the emergence of a dominant logic. However, extant research on dominant logic – while recognizing the political processes – has largely ignored it. Second, developing the links between dominant logic and institutional logic (Hill 2000; Thornton et al. 2012) seems very promising. Finally, we see great potential for studying the impact of dominant logic on the evolution of adaptive goals since dominant logic is formed through goal-directed processes and, in turn, affects goal adaptation.

References

Baden-Fuller, C., and M. Morgan. 2010. Business models as models. Long Range Planning 43: 156–171.

Bettis, R.A., and C.K. Prahalad. 1995. The dominant logic: Retrospective and extension. Strategic Management Journal 16: 5–14.

Bettis, R.A., S.S. Wong, and D. Blettner. 2011. Dominant logic, knowledge creation, and managerial choice. In Handbook of organizational learning and knowledge management, ed. M. Easterby-Smith and M.A. Lyles. New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Billinger, S., N. Stieglitz, and T.R. Schumacher. 2013. Search on rugged landscapes: An experimental study. SSRN. Available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1711743.

Black, J., F.H. Fabian, and K. Hinrichs. 2005. Fractals, stories and the development of coherence in strategic logic. Competence-Based Strategic Management Applications 7: 421–441.

Brännback, M., and P. Wiklund. 2001. A new dominant logic and its implications for knowledge management: A study of the Finnish food industry. Knowledge and Process Management 8: 197–206.

Coté, L., A. Langley, and J. Pasquero. 1999. Acquisition strategy and dominant logic in an engineering firm. Journal of Management Studies 36: 919–952.

D’Aveni, R.A., D.J. Ravenscraft, and P. Anderson. 2004. From corporate strategy to business-level advantage: Relatedness as resource congruence. Managerial and Decision Frames 25: 365–381.

Gary, M.S., and R.E. Wood. 2011. Mental models, decision rules, and performance heterogeneity. Strategic Management Journal 32: 569–594.

Gary, M.S., R.E. Wood, and T. Pillinger. 2012. Enhancing mental models, analogical transfer, and performance in strategic decision making. Strategic Management Journal 33: 1129–1246.

Ginsberg, A. 1989. Construing the business portfolio: A cognitive model of diversification. Journal of Management Studies 26: 417–438.

Hamel, G., and C.K. Prahalad. 1994. Competing for the future. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Hill, C.W.L. 2000. Dominant logic and the iron cage: Economics meets sociology in strategic management. In Advances in strategic management, vol. 17, ed. J. Baum and F. Dobbin. England: Emerald Group Publishing.

Jarzabkowski, P. 2001. Dominant logic: An aid to strategic action or a predisposition to inertia? Working paper No. RPO 110. Birmingham: Aston Business School Research.

Jenkins, M., and G. Johnson. 1997. Entrepreneurial intentions and outcomes: A comparative causal mapping study. Journal of Management Studies 34: 895–920.

Lampel, J., and J. Shamsie. 2000. Probing the unobtrusive link: Dominant logic and the design of joint ventures at general electric. Strategic Management Journal 21: 593–602.

Nadkarni, S., and V.K. Narayanan. 2005. Validity of the structural properties of text-based causal maps: An empirical assessment. Organizational Research Methods 8: 9–40.

Nadkarni, S., and V.K. Narayanan. 2007. Strategic schemas, strategic flexibility, and firm performance: The moderating role of industry clockspeed. Strategic Management Journal 28: 243–270.

Obloj, K., and M. Pratt. 2005. Happy kids and mature losers: Differentiating dominant logics of successful and unsuccessful firms in emerging markets. In Strategy in transition, ed. R. Bettis. Oxford: Blackwell.

Obloj, T., K. Obloj, and M. Pratt. 2010. Dominant logic and entrepreneurial firms’ performance in transition economy. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 34: 151–170.

Porac, F.J., Y. Mishina, and T.C. Pollock. 2002. Entrepreneurial narratives and the dominant logics of high-growth firms. In Mapping strategic knowledge, ed. A. Huff and M. Jenkins. London: Cromwell Press.

Prahalad, C.K. 2004. The blinders of dominant logic. Long Range Planning 37: 171–179.

Prahalad, C.K., and R.A. Bettis. 1986. The dominant logic: A new linkage between diversity and performance. Strategic Management Journal 7: 485–501.

Ray, S., and R. Chittoor. 2005. Re-evaluating the concept of dominant logic: An exploratory study of an Indian business group. Calcutta: Indian Institute of Management.

Rumelt, R. 2011. Good strategy/bad strategy: The difference and why it matters. New York: Random House.

Santos, F.M., and K.M. Eisenhardt. 2009. Constructing markets and shaping boundaries: Entrepreneurial power in nascent fields. Academy of Management Journal 52: 643–671.

Teece, D.J. 2010. Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long Range Planning 43: 172–194.

Thornton, P.H., W. Ocasio, and M. Lounsbury. 2012. The institutional approach to culture, structure, and process. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Von Krogh, G., and J. Roos. 1996. A tale of the unfinished. Strategic Management Journal 17: 729–737.

Von Krogh, G., P. Erat, and M. Macus. 2000. Exploring the link between dominant logic and company performance. Creativity and Innovation Management 9: 82–93.

Wright, R.P. 2008. Eliciting cognitions of strategizing using advanced repertory grids in a world constructed and reconstructed. Organizational Research Methods 11: 753–769.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Copyright information

© 2018 Macmillan Publishers Ltd., part of Springer Nature

About this entry

Cite this entry

Bettis, R.A., Blettner, D. (2018). Dominant Logic. In: Augier, M., Teece, D.J. (eds) The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Strategic Management. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-00772-8_575

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-00772-8_575

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, London

Print ISBN: 978-0-230-53721-7

Online ISBN: 978-1-137-00772-8

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementReference Module Humanities and Social SciencesReference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences