Abstract

Subjective lying rates are often strongly and positively correlated. Called the deception consensus effect, people who lie often tend to believe others lie often, too. The present paper evaluated how this cognitive bias also extends to deception detection. Two studies (Study 1: N = 180 students; Study 2: N = 250 people from the general public) had participants make 10 veracity judgments based on videotaped interviews, and also indicate subjective detection abilities (self and other). Subjective, perceived detection abilities were significantly linked, supporting a detection consensus effect, yet they were unassociated with objective detection accuracy. More overconfident detectors—those whose subjective detection accuracy was greater than their objective detection accuracy—reported telling more white and big lies, cheated more on a behavioral task, and were more ideologically conservative than less overconfident detectors. This evidence supports and extends contextual models of deception (e.g., the COLD model), highlighting possible (a)symmetries in subjective and objective veracity assessments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

How often do people lie? This question has been examined for decades in deception scholarship, with most evidence suggesting that people report telling one-to-two lies per day, on average1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. This finding is pancultural11, and it is also misleading. While most people are self-reportedly honest, there a few greater-than-average “outliars” in a population who skew the distribution to the right6,9,12,13. Such lie prevalence findings—in terms of rate and distribution—are some of the most stable, consistent, and reliable deception results in the extant literature14.

Lying rates have been linked to a range of characteristics that help to indicate how lie-tellers may function socially and psychologically. For example, greater-than-average lying rates are associated with certain individual differences (e.g., people who are young and male tend to tell more lies than the average person)6,9. Those who are high on aversive personality traits (e.g., psychopathy)6,12 and low on dispositional honesty-humility15 tend to lie more than the average person as well16. Crucially, prior work has also observed an interpersonal finding where lying rates, characterized by actual deceptive behavior and self-reported lying frequencies, are positively associated with other-perceived lying rates6,7,17. In other words, the more that people lie, the more they think that others are lying to them (or in, general) as well6,7. Called the deception consensus effect7, and derived from false consensus effect research in social psychology18, this bias reveals how others think about deception as a social and interpersonal phenomenon, indicating the possible cognitive biases people may have about deception production19. Since its development, the deception consensus effect has been replicated in different settings17, with stronger results for those who lie prolifically than those who engage in everyday lying6.

While the deception consensus effect is rooted in lie production research, it is unclear if perceptions of self and other detection abilities are also related, henceforth referred to as a detection consensus effect. If self- and other-perceived detection rates are indeed linked, and such variables also connect to one’s objective detection ability, this might help to illuminate various social, psychological, and cognitive pathways that impact deception judgments. Deception detection research is often focused on veracity from an intrapersonal perspective, considering how a person’s internal characteristics might associate with detection ability. More work is needed to understand how social and interpersonal perceptions may associate with detection as well. To this end, two studies were conducted—one with university students and one with the general public—to evaluate the detection consensus effect.

Contextual factors impacting deception production and deception detection

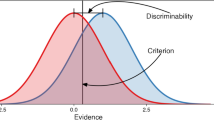

Overwhelming evidence in the deception detection literature suggests that on average, people are often slightly greater than chance at lie-truth judgments20. Deception detection accuracy tends to hover around 54%, with truths being evaluated more accurately than lies because people are truth-biased21. The distribution of deception detection accuracy is also remarkably normal14,22. People are often poor deception detectors—and slightly-greater-than-chance detection accuracy remains a stable finding, on average—not because they rely on cues that are unreliably associated with deception, but because the cues they do rely on are typically faint23. In sum, deception detection is a challenge for most people, and lie-truth judgments are often impacted by signals that can be misleading, mixed, or fallible.

People are also typically truth-biased—they infer honesty independent of message veracity—and remain in a truth-default state until a trigger kicks them out24, making them suspicious of the message sender. Indeed, people often detect lies by using third-party or physical evidence25, and detection accuracy can increase with more strategic, active, and context-sensitive question-asking26,27,28,29, using content in context (e.g., aspects of the situation to identify contradictions)30,31, and strategically using evidence when interviewing suspects32, among many others33. More recent theorizing in deception research, however, has argued for a context-driven approach toward understanding lie production (e.g., why people deceive and how they communicate deceptively) and lie detection (e.g., aspects of the context that impact or relate to deception detection abilities). One particular theoretical model that supports this idea is the Contextual Organization of Language and Deception (COLD) model34,35. The model by Markowitz and colleagues argues there are several aspects of a deception context that impact lie production and detection: (1) psychological dynamics (e.g., the emotional and cognitive experience of the deceiver), (2) pragmatic goals (e.g., what the deceiver is trying to accomplish), (3) genre conventions (e.g., norms and community traits that shape how people communicate, independent of deception), (4) individual-level factors (e.g., individual differences like personality characteristics that relate to deception), (5) situation-level factors (e.g., aspects of the setting that facilitate deception, like providing people with an opportunity to cheat), and most relevant to the current investigation (6) interpersonal factors34.

Context-related interpersonal factors include who people are communicating to, the relationship between message sender and receiver, and how often the message sender thinks others may be lying (e.g., the deception consensus effect). Recall, Markowitz and Hancock7 observed that online daters who lied at high rates also believed that they were being lied to at high rates as well—a strong, positive association between subjective, self- and other-perceived deception production. How often people lie is therefore impacted, or at least linked to, how often they perceive that others might be lying. Interpersonal perceptions of deception are therefore a contextual factor associated with lie production34,36.

Are interpersonal factors like perceptions of self and other deception detection abilities also linked, therefore requiring them to be considered as context-related elements of deception detection? To the best of my knowledge, this question has received limited treatment and remains under-examined in deception research at large—but, it remains theoretically-motivated by the COLD model based on its assumption that egocentric biases impact both lie production and detection. It is critical to note that this assumption has not been formally tested, which is why an empirical endeavor like the one undertaken in the current paper is worthwhile and necessary for theory building. This idea is also supported by evidence that suggests some people may have a deception-general ability. For example, Wright and colleagues37 observed that those who could lie successfully in an opinion-giving task were those who could also detect the false and truthful opinions of others successfully. In other words, some people who are (successful) liars may have greater-than-average detection deception abilities, or a sense of when other people may be lying37. For transparency, it is important to note that Wright and colleagues focused on successful liars, or people whose deceptive messages were difficult to discriminate from truths. In the current work, this argument is extended beyond the success of the deceiver and instead, to how often they lie. The basic idea suggests the more people lie, the better they may be at distinguishing lies from truths. While the exact mechanism for this pattern is unclear, it is possible that people who lie a lot or who are successful at lying may intuit or have a sense of when others are being deceptive. Importantly, and for the purposes of the present paper, people who lie a lot may use this sense to guide their perceptions of how often lying occurs in daily life and if it can be detected. Taken together, since self- and other-perceived lying rates are positively correlated for most people (i.e., the deception consensus effect), a reasonable and open empirical question therefore asks if this phenomenon extends to detection:

- RQ1::

-

To what degree are self- and other-perceived deception detection rates correlated, revealing a detection consensus effect?

The perception and misperception of deception detection ability

While the present work is principally interested in how self- and other-perceived judgments in deception detection are linked, it simultaneously examines how such subjective perceptions are associated with objective detection ability. There is good reason to suspect that the link between subjective perceptions and objective detection ability may be faint or unreliable, however. Judgment and decision-making research suggests people often have (mis)guided perceptions of their own objective abilities for various tasks19,38,39. Studies have observed people believe they are better-than-average drivers40, over 90% of college professors suggest their work is “above average”41, and people who answer general knowledge questions overestimate their correctness42. In other words, people often have inflated perceptions of their ability, making the link between subjective and objective abilities asymmetric across domains43,44,45.

In deception research, specifically, asymmetries are commonly observed for beliefs about the cues that can reveal dishonesty and detection abilities. For example, while most deception cues are objectively faint, unreliable, or substantially moderated by contextual factors46,47,48, people often believe that eye gaze aversion reveals a liar despite it having little-to-no diagnostic value49. More generally, cue theories describe communicative tells that can reveal a liar from a truth-teller50,51,52,53,54; at best, however, the evidence is mixed to suggest the social, psychological, or behavioral cues of dishonesty. Therefore, subjective beliefs about the cues that reveal deception, and objective evidence about the cues that reliably reveal deception, are typically inconsistent.

The ubiquity of the truth-bias also suggests people may often fall for others’ deception. For example, early research has revealed that people are often inaccurate in detecting deception with romantic partners55,56,57. Most people are unsuspicious of their partners, leading to mostly true judgments, therefore decreasing detection accuracy. This asymmetry is exacerbated when lie-truth base-rates are adjusted; detection accuracy tends to improve when the proportion of true-to-false messages increases because most people are truth-biased21. People are therefore inaccurate in their assessment of how often they believe others are lying and this inevitably reduces their detection ability.

Altogether, people may have inaccurate perceptions of subjective and objective detection abilities due to the use of faint deception signals23. Indeed, perceptions of one’s ability are unreliably linked objective detection accuracy, as a classic meta-analysis observed no evidence for an accuracy-confidence correlation in deception detection58. That is, across 18 samples, the correlation between how confident people felt in their veracity judgments and deception detection accuracy was incredibly small and not statistically significant (r = 0.04). The degree to which subjective and objective detection abilities are linked have been narrowly studied in the literature, and represent the second research question in this empirical package:

- RQ2::

-

What is the relationship between subjective and objective deception detection accuracies?

Note, in this work, the evaluation of one’s subjective and objective detection abilities also helped to facilitate an exploration into those who have inflated perceptions of their own detection ability relative to their actual detection ability. The current research used several exploratory analyses to examine two ideas: (1) personal overconfidence, defined as one’s perceived detection ability relative to their actual ability, and (2) social overconfidence, defined as one’s perceived detection ability relative to the perceived detection ability of others. It is unclear if such overconfidence variables can be predicted by dimensions of interest in this empirical package and therefore, the current work explored such possibilities.

- RQ3::

-

What is the relationship between overconfidence, lie production, and lie detection measures?

The current study

Taken together, to understand how subjective self- and other-perceived deception detection rates are linked and to formally test such interpersonal deception detection assumptions made by the COLD model, samples were collected from university students (Study 1) and the general public (Study 2). In both studies, people made 10 lie-truth judgments, and rated their own subjective detection ability plus how often they think people can accurately distinguish between lies and truths. This work is timely and important because it is presently unclear if deception detection ability, and perceptions of such ability, can be characterized by interpersonal perceptions like the detection ability of others. To the degree that actual (or perceived) detection ability is linked to interpersonal perceptions, this may help to advance our understanding of the cognitive biases associated with deception detection and how such contextual aspects of deception are associated.

Study 1: Method

Participants and power

An a priori power analysis, reported in this paper’s preregistration on AsPredicted (https://aspredicted.org/6FN_WTF), ensured that enough participants were collected for this study. The effect size estimate was drawn from prior work evaluating the deception consensus effect6,7. In these studies, effect sizes for the relationship between self- and other-perceived lying rates ranged from medium (ρ = 0.40, p < 0.001) to large (ρ = 0.70, p < 0.001) and therefore, the lower end of this range was used as a conservative estimate of how self- and other-perceived detection accuracy might be linked. Using a medium effect size (ρ = 0.40) powered at 80% (α = 0.05, two-tailed), at least 46 participants were required. This work nearly quadrupled the sample size based on this estimate to ensure enough participants were recruited (N = 180), and the sample consisted of university students from the author’s home institution. This sample size is within range of other deception detection studies59,60,61. All procedures and measures in this paper were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and approved by the Michigan State University Institutional Review Board (STUDY00010148). Informed consent was obtained from all participants in each study as well.

Participants were mostly women (n = 114; 63.3%), 19.7 years old (SD = 1.3 years) on average, and were mostly White (n = 123; 68.3%), followed by others of different ethnicities (i.e., Asian n = 26; Black or African American n = 12, Other n = 5, Hawaiian n = 1, American Indian n = 1; others did not disclose). On average, participants leaned left politically (M = 3.70, SD = 1.43; 1 = extremely liberal, 7 = extremely conservative).

Procedure

Participants were recruited from the Department of Communication’s research subject pool for a deception detection study. The first part of the study told participants that they would watch 10 short videos of videotaped interviews62. These videotaped interviews, and instructions below, are well-established for detection tasks and have been used extensively in the deception literature4,28,30,60,63,64,64,65. Based on such work, participants were given the following prompt:

You will see 10 videotaped interviews. The basic situation is always the same but the person being interviewed is different. These clips are of interviews with Michigan State University students who participated in a study about teamwork. Each subject had just played a trivia game with a partner for a cash prize. All participants had the opportunity to cheat when the experimenter was called out of the room, and the answers were left in a folder within easy reach of the participants. Some participants cheated and others did not. All the people being interviewed on these tapes denied cheating. Not all of them are honest. Some but not all of them are lying about cheating. Your task is to do your best to identify who cheated and is lying and who is being honest about not cheating.

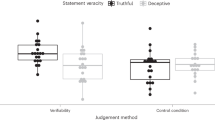

The videos were drawn from a pool of 20 total videos (10 with ground truth honesty, 10 with ground truth dishonesty), and participants were presented with 10 randomly selected videos, after which they made a binary choice: the person in the video was (1) an honest, non-cheater, or the person in the video (2) cheated and lied about it. After the detection task, participants answered several questionnaire items. These questions fell into two main categories: (1) subjective deception detection abilities of the self and others, and (2) subjective lying rates of the self and others. Finally, participants reported demographics and the survey ended.

Measures

Objective detection accuracy

Deception detection accuracy was calculated as the number of correctly judged lies and correctly judged truths divided by the total number of messages judged14,66,67. The resulting measure is a percentage based on 10 trials.

Subjective detection ability

To evaluate the detection consensus effect—the idea that perceived self and other deception detection rates are positively correlated—two questions were asked of participants and adapted from prior work68. The first question asked, “On a scale of 0% (none of the time) to 100% (all of the time), how often do you think you can detect if someone is lying or deceiving you?” and participants used a slider to indicate their answer. The second question asked, “On a scale of 0% (none of the time) to 100% (all of the time), how often do you think other people can detect if someone is lying or deceiving you?” and participants used a slider. The initial position of each slider was fixed at 50%, and questions were randomized.

Subjective lying rates

Consistent with prior work evaluating the deception consensus effect6,9, participants reported how often they told little white lies and big, serious lies. For self-focused questions, participants responded to the following questions: (1) “On average, how many times a day do you tell a little white lie?” and (2) “On average, how many times a day do you tell a big, serious lie?” Question order was randomized. For other-focused questions, participants responded to similar questions: (1) “On average, how many times a day do you think other people tell a little white lie?” and (2) “On average, how many times a day do you think other people tell a big, serious lie?” There were 10 response options: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25+. The order of the other-focused questions was also randomized. The order of self-versus other-focused questions was randomized as well. Across questions, all 25+ responses were recoded as 25.

Personal and social overconfidence

Since subjective and objective detection abilities were recruited, this facilitated an opportunity to explore how overconfidence related to various individual differences (e.g., age, conservatism), and various lie production variables. Personal overconfidence was defined via the following formula: self-perceived detection ability minus objective detection accuracy, to obtain a general sense of one’s perceived detection ability relative to their actual ability. Social overconfidence was defined via the following formula: self-perceived detection ability minus other-perceived detection ability, to obtain a general sense of one’s perceived detection ability relative to their perceived detection ability of others. On these measures, high numbers represent people who believe they are better detectors than their actual or others’ ability.

Analytic plan

Recall, lying rates are often not normally distributed7,9,14,67,69. Therefore, non-parametric tests (Spearman’s ρ) were conducted to evaluate how subjective (self and other perceptions of lying and detection ability) and objective detection abilities are linked.

Study 1: Results

Descriptive findings

Descriptive statistics across key variables are in Table 1. The average deception detection accuracy across participants was 52.78% (SD = 20.63%). Participants were also truth-biased in that they judged most videos to be true (M = 52.39%, SD = 18.23%), a value that was marginally greater than 50% via a one-sided t-test, t(179) = 1.76, p = 0.08.

Figure 1 also presents histograms of the key variables, which revealed expected effects from the deception literature14: self-reported lying rates are not normally distributed, most people are relatively honest, there are a few individual who engage in prolific lying (greater-than-average lying), and detection accuracy is more normally distributed.

The detection consensus effect and the deception consensus effect

Table 2 suggested objective deception detection accuracy was not statistically linked to any perceived detection ability metric (ps > 0.401). However, objective detection accuracy was inversely associated with how often people reported telling big lies (ρ = -0.154, p = 0.046) and how often they believe others tell big and serious lies, on average (ρ = -0.173, p = 0.025). In other words, students who were objectively less accurate lie detectors tended to self-report more big and serious lies, and suggest that others also tell more big and serious lies, too.

Supporting the idea of a detection consensus effect, self- and other-perceived detection abilities were statistically linked (ρ = 0.378, p < 0.001). Finally, as expected by the deception consensus effect, white lying frequencies (ρ = 0.659, p < 0.001) and big lying frequencies were also statistically linked (ρ = 0.464, p < 0.001).

Note, the detection consensus effect does not assume who is being lied to when making “other” detection perceptions. To evaluate if the target of who is being lied to matters, however, new Prolific participants (N = 70) were recruited based on an a priori power analysis estimating the average effect size from Study 1 and 2 (ρ = 0.481) at 99% power (α = 0.05, two-tailed). The relationship between self- and other-perceived detection abilities when the other detection rate is framed as “how often do you think other people can detect if someone is lying or deceiving you?” was strong (ρ = 0.503, p < 0.001). When the other detection rate is framed as “how often do you think other people can detect if someone is lying or deceiving them?,” the correlation was also strong (ρ = 0.596, p < 0.001). Using Pearson coefficients for these measures (r = 0.546 and r = 0.627, respectively), and comparing correlations using z-transformations70, the magnitude of the correlations were not statistically different from each other (z = -1.25, p = 0.212). Therefore, who is being lied to does not appear to impact the results at least in this sample, which speaks to the expected and intended generality of the detection consensus effect.

Exploratory overconfidence results

Personal overconfidence was positively associated with the perceived detection ability of other people (ρ = 0.262, p = 0.001) and big lying rates of others as well (ρ = 0.245, p = 0.002). Therefore, people who have an inflated sense of their own deception detection ability also consider the deception detection abilities of others to be greater (and they believe others tell more serious lies, too).

Social overconfidence was positively associated with big lying rates of others (ρ = 0.176, p = 0.026). Social overconfidence was unassociated with actual detection accuracy (ρ = -0.069, p = 0.389). Note, given the constrained demographics of a student sample, links between subjective and social overconfidence and individual differences (e.g., age, gender) were not evaluated.

Together, Study 1 finds support for the idea that self-other perceived detection abilities (i.e., the detection consensus effect) and lying rates (i.e., the deception consensus effect) are positively correlated. Actual detection ability was also largely uncorrelated with most self-report variables measured in this study. There are several limitations of this first study that require additional research. First, the participants in this study were college students and it is therefore unclear if such findings extend beyond those at university. Younger individuals also tend to lie more than older individuals6,9,71, suggesting that a sample of older participants is necessary to assess the robustness of the reported findings. Second, while detection accuracy was measured in the current work and revealed null associations with self-reported deception detection and white lying rates, actual deceptive behavior was not measured in Study 1. Prior work suggests there are small, systematic associations between self-reported lying frequencies and deceptive behavior (e.g., cheating)6,69, and therefore, the next study measured how self-reported deception detection and production rates link to one’s own deceptive behavior. Finally, in the spirit of replication and open science, Study 1 was one of the first to evaluate the detection consensus effect, formally testing its evidentiary value in accordance with the COLD model, and only a few studies have measured the deception consensus effect as well6,7,17,72. Research that replicates such findings will add credibility to the current empirical package.

Study 2: Method

Participants and procedure

A total of 250 US participants were recruited from Prolific. Participants were paid $4.00 for their time in a 20-min study. Most participants self-identified as women (n = 126, 50.4%; men n = 117, 46.8%; other n = 5, 2.0%), were 37.4 years old (SD = 12.31 years), and were mostly White (n = 167, 66.8%; other ethnicities included Black or African American n = 49, Asian n = 23, Other n = 11). On the political ideology scale (1 = extremely liberal, 7 = extremely conservative), participants leaned left, on average (M = 3.03, SD = 1.57).

The procedure, measures, and analytic plans were identical to Study 1, though one measure of deceptive behavior was added before the demographic questions. Consistent with prior work6,73, participants were told they would unscramble letters to form words in English. There were eight trials to be completed within two minutes, and the trials were presented in random order, yet three were unsolvable (e.g., they did not have an answer: OPOER, ALVNO, ANDHU). Participants self-scored their performance, indicating if they solved or did not solve the word unscrambling task. Blank responses were counted as not solved. Scores on the unsolvable trials that were claimed to be solved were summed (min = 0, max = 3) as a proxy for deceptive behavior or cheating.

Study 2: Results

Descriptive findings

Average detection accuracy was 57.20% (SD = 17.03%). Participants were also truth-biased in that they judged most videos to be true (M = 61.36%, SD = 16.10%), a value that was significantly greater than 50% via a one-sided t-test, t(249) = 11.16, p < 0.001. Figure 2 presents histograms of the key variables, which describe that self-reported lying rates were not normally distributed. Objective deception detection accuracy was more normally distributed.

The detection consensus effect and the deception consensus effect

Table 3 suggests objective deception detection accuracy was not statistically associated with any perceived detection nor production metric (ps > 0.092). However, perceived self and other detection abilities were statistically linked (ρ = 0.584, p < 0.001), supporting the detection consensus effect also observed in Study 1. Finally, white lying frequencies (ρ = 0.592, p < 0.001) and big lying frequencies were also statistically linked (ρ = 0.500, p < 0.001), supporting the deception consensus effect observed here and in other studies.

Connection to deceptive behavior

How do the various detection and production measures associate with one’s deceptive behavior? The number of unsolvable anagrams was associated with objective detection accuracy, subjective detection ability, and perceived lying rates. Deceptive behavior was statistically unassociated with detection accuracy (ρ = − 0.017, p = 0.795) and other-perceived deception detection ability (ρ = 0.042, p = 0.512), but it was positively associated with one’s self-perceived ability to detect deception (ρ = 0.144, p = 0.023).

Deceptive behavior was not statistically associated with one’s self-reported white lying rate (ρ = 0.074, p = 0.242), but as expected by prior work, it was statistically associated with one’s self-reported big lying rate (ρ = 0.167, p = 0.008). Deceptive behavior was not statistically associated with the other-perceived white lying rate (ρ = 0.065, p = 0.303), but it was statistically associated with the other-perceived big lying rate (ρ = 0.197, p = 0.002). Cheating, and its link to self-reported lying rates, may therefore be sensitive to lie type (serious lies vs. white lies).

Exploratory overconfidence results

Personal overconfidence was positively associated with various individual differences, including conservative political ideology (ρ = 0.152, p = 0.017) and age (ρ = 0.124, p = 0.049), but not gender [F(2, 245) = 2.27, p = 0.106] nor ethnicity [F(3, 246) = 1.45, p = 0.229]. Social overconfidence was positively associated with conservative political ideology (ρ = 0.162, p = 0.010) and gender [F(2, 245) = 3.02, p = 0.051], but not age (ρ = − 0.058, p = 0.359), nor ethnicity [F(3, 246) = 1.19, p = 0.315]. Women were less socially overconfident than men (B = − 5.44, SE = 2.40, t = − 2.27, p = 0.024), a finding generally supported by prior work58.

Personal overconfidence was also positively associated with one’s self-reported white lying rate (ρ = 0.130, p = 0.040), big lying rate (ρ = 0.147, p = 0.020), and others’ white lying rate (ρ = 0.169, p = 0.007) and big lying rate (ρ = 0.163, p = 0.009). When treating personal overconfidence dichotomously (e.g., overconfident individuals were those whose score was greater than zero on the subtraction metric, n = 94; underconfident individuals were those whose score was less than or equal to zero on the subtraction metric, n = 156), consistent results emerged. Personally overconfident individuals (M = 2.95, SD = 3.94) reportedly told marginally more white lies than personally underconfident individuals (M = 2.09, SD = 2.80), t = 1.84, p = 0.067, Cohen’s d = 0.25. Personally overconfident individuals (M = 0.84, SD = 2.62) reportedly told more big lies than personally underconfident individuals (M = 0.23, SD = 0.67), t = 2.21, p = 0.029, Cohen’s d = 0.32. Personally overconfident individuals (M = 5.32, SD = 4.76) reportedly believed other people told more white lies than personally underconfident individuals (M = 4.02, SD = 3.64), t = 2.28, p = 0.024, Cohen’s d = 0.31. Finally, personally overconfident individuals (M = 2.14, SD = 3.23) reportedly believed other people told more big lies than personally underconfident individuals (M = 1.17, SD = 1.52), t = 2.74, p = 0.007, Cohen’s d = 0.39. The difference between subjective and objective detection abilities may be a heuristic to indicate those who have inflated perceptions of lying prevalence, and certain demographic traits.

Finally, deceptive behavior represented by cheating via the anagram task was positively associated with personal overconfidence (ρ = 0.142, p = 0.024) and marginally associated with social overconfidence (ρ = 0.111, p = 0.081). Therefore, one possible pathway toward a deeper understanding of those who might be overconfident in their own detection ability may be to assess their own one-shot deceptive behavior.

General discussion

The current paper drew on prior lie production findings via the COLD model, namely the idea that self- and other-perceived lying rates are strongly correlated, and extended this phenomenon to deception detection. Here, self- and other-perceived lie detection accuracies were also strongly correlated, supporting a detection consensus effect. Therefore, a major theoretical advance of this work is a formal test of context-related factors that have been assumed to matter and associate with each other for deception detection: how people perceive the detection abilities of the self and others. Two studies indeed found evidence of a strong interpersonal link between self- and other-detection abilities. Crucially, however, one’s objective detection ability was unassociated with most subjective detection and production perception measures. Asking people how well they can detect lies is therefore problematic, as it has little diagnostic utility to predict actual detection ability. Exploratory evaluations of overconfidence also revealed that people who believed they had better deception detection ability tended to cheat more, self-report more white and big lies, and be more ideologically conservative.

There are several contributions of this paper worth highlighting. First, this paper introduces some of the first self- and other-perceived (a)symmetries in deception detection ability. This evidence matters because it suggests a burgeoning lie production finding—the deception consensus effect—also extends to detection. Unlike the deception consensus effect, however, which often links to deceptive behavior like cheating, the detection consensus effect does not appear to associate with objective detection ability like detection accuracy. This is a critical finding because it suggests one’s perceptions of their detection ability and the reality of detection ability are distinct. It is ineffective, or at least inaccurate, to consider how subjective perceptions of one’s detection ability link to objective detection ability; still, subjective detection perceptions may be a useful indicator of other deception patterns, including those that are involved in lie production. The results in Table 3 suggested those with higher subjective (personal) detection abilities also self-reported more white and big lying, more perceived white and big lying from others, and more behavioral deception. Asking people to self-report their detection ability might not be a helpful heuristic for detectors, but it may be helpful for identifying deceivers, though much more work would be needed to examine this contention systematically and to move beyond self-reports.

A second advance relates to the strength of the deception consensus effect and the detection consensus effect. The strong correlations between self- and other-perceived lying and self- and other-perceived detection abilities underscore a pervasive cognitive bias, where individuals project their own perceived actions and abilities onto others. The theoretical origins of these effects are from social psychology research, namely egocentric cognitive biases that suggest people perceive the behavior of others based on their own behavior18,74. A body of evidence has established the reliability of the deception consensus effect6,7,17, yet little work has examined cognitive biases associated with self- and other-perceived detection until the current paper. Therefore, support for the detection consensus effect has been established here, amplifying and extending cognitive bias research related to deception in new ways. This pattern of results requires replications and extensions in future work to establish their robustness. It is also worth noting that the magnitudes of the deception consensus effect and detection consensus effect were more substantial in size than other relationships reported in this paper. Perhaps this suggests self-report deception data are more tightly linked or consistently reported than behavioral data, which is important for deception scholars to consider when recruiting information about how people think, feel, and respond to deception stimuli.

Third, this work provides evidence for and extends the COLD model in new directions. For example, the COLD model posits that interpersonal factors like self- and other-perceptions of deception are linked for lie production, but extant evidence was relative unclear or non-existent for deception detection. That the detection consensus effect exists, is robust across various samples (students, the general public), and has a substantial effect size adds complexity and nuance to the COLD model by showing that while people may be biased toward believing others are truthful, they also think about others’ detection ability in ways that are similar to how they think about their own detection ability, and they simultaneously overestimate their ability to detect deception. It is important to underscore the theoretical and practical impact of such findings. The combination of truth-bias and overconfidence in lie detection ability may complicate trust and suspicion in social interactions. Relatedly, the overconfidence findings suggest people who believed they had greater detection ability than their objective detection ability tended to have certain defining internal traits (e.g., they were generally older and more ideologically conservative). Overconfident individuals also self-reported more lying and more perceived lying by others. It is possible that overconfident individuals represent a subclass of people who have unique thoughts, feelings, and perspectives on deception, in general. Like those who engage in prolific lying, who have various individual differences associated with them, and are a separate population6,8,9,12, overconfident detectors may have defining characteristics to them, and represent a distinct group of people. The concept of overconfident detectors has not been extensively explicated in the deception literature (though, relatedly, see DePaulo and colleagues58), and deserves more treatment in future research. Relatedly, the findings in this work call into question the effectiveness of training programs aimed at improving lie detection skills. Given the weak correlation between perceived and actual detection abilities, training efforts might need to perhaps focus on mitigating overconfidence and improving understanding of the limitations in human deception detection capabilities.

Finally, it is worth discussing why certain findings may have been inconsistent across studies of the current empirical package. In Study 1, objective detection accuracy was negatively associated with self- and other-perceived big lying rates, while these relationships failed to obtain in Study 2. Why did these mixed findings emerge? Prior work suggests teenagers tend to self-report telling nearly 4 lies per day, on average71, which is much larger than the average for other groups of people. If we combine the self-reported white and big lying rates of the students in Study 1, the average was 3.93 lies per day (SD = 4.00 lies per day), which is close to the rate reported in such prior work. Therefore, it is possible that university students, young adults, and teenagers are a separate group of people altogether when reporting on their perceptions and judgments of deception and its detection. This insight offers possible moderators of the effects reported for production and detection effects. Future work should attempt to understand how people of various backgrounds and demographic makeups detect deception, and how such characteristics comparatively relate to detection and production.

Limitations and future directions

The current study has several limitations that should be resolved in future research. Chief among them is the idea that the detection tasks were relatively short, and people made prompted judgments about veracity. It is possible that deception may not come to mind for some people unless they are prompted75. Therefore, prompting versus un-prompting veracity judgments in future work would help to evaluate the robustness of the evidence reported in the current paper. Relatedly, participants were not given examples of white or big lies when the production measures were recruited; therefore, across participants, error variance may have been introduced by way of different subjective understandings of these constructs. Future work should provide formal definitions of white and big lies to ensure consistent interpretations and grounding.

Second, the results in this work are bounded by the stimuli used to derive them. That is, detection accuracy is based on the well-validated videotaped interviews by Levine62, but more diverse stimuli should be considered in future research. These videos were used because they are valid and reliable stimuli in the deception detection literature that could be deployed at scale to students and those in the public. For one of the first tests of the detection consensus effect, this paper intentionally used empirically-trusted stimuli.

Third, effect size estimates in this study were based on the deception consensus effect, and similar effect sizes were obtained for the detection consensus effect. It is possible that for some relationships, smaller effect sizes would be expected and therefore, more participants would be required to detect a reliable relationship. This is a consideration for future research as well. Future research may also consider using different cheating tasks to assess deceptive behavior. This was a one-off assessment of cheating, and it is possible that people may cheat in some scenarios and not others. Assessing the effects longitudinally is important for future work, along with the possibility that certain relationships in this paper might be amplified or attenuated based on one’s lie production status (e.g., as someone who lies prolifically or as someone who is an everyday liar). For example, if sufficient sample sizes can be obtained across lie production categories, future work might explore how one’s status as someone who lies prolifically modifies the detection consensus effect or other patterns reflected in this research. Finally, future studies should examine the mental processes that underly the detection consensus effect (and the deception consensus effect as well). Exploring the psychological mechanisms associated with such relationships were beyond the scope of the current work, but deception scholarship would benefit from attempting to understand why such patterns occurred.

Data availability

Underlying data for this paper are located on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/7uwhj/?view_only=f0ee86ad005f48ff81537549633bb72b.

References

DePaulo, B. M., Kirkendol, S., Kashy, D., Wyer, M. & Epstein, J. Lying in everyday life. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 70, 979–995 (1996).

George, J. F. & Robb, A. Deception and computer-mediated communication in daily life. Commun. Rep. 21, 92–103 (2008).

Hart, C. L., Jones, J. M., Terrizzi, J. A. & Curtis, D. A. Development of the lying in everyday situations scale. Am. J. Psychol. 132, 343–343 (2019).

Levine, T. R., Serota, K. B. & Shulman, H. C. The impact of lie to me on viewers’ actual ability to detect deception. Commun. Res. 37, 847–856 (2010).

Markowitz, D. M. et al. Revisiting the relationship between deception and design: A replication and extension of Hancock et al. (2004). Hum. Commun. Res. 48, 158–167 (2022).

Markowitz, D. M. Toward a deeper understanding of prolific lying: Building a profile of situation-level and individual-level characteristics. Commun. Res. 50, 80–105 (2023).

Markowitz, D. M. & Hancock, J. T. Deception in mobile dating conversations. J. Commun. 68, 547–569 (2018).

Serota, K. B., Levine, T. R. & Docan-Morgan, T. Unpacking variation in lie prevalence: Prolific liars, bad lie days, or both?. Commun. Monogr. 89, 307–331 (2022).

Serota, K. B. & Levine, T. R. A few prolific liars: Variation in the prevalence of lying. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 34, 138–157 (2015).

Verigin, B. L., Meijer, E. H., Bogaard, G. & Vrij, A. Lie prevalence, lie characteristics and strategies of self-reported good liars. PLoS ONE 14, e0225566–e0225566 (2019).

Serota, K. B., Levine, T. R., Zvi, L., Markowitz, D. M. & Docan-Morgan, T. The ubiquity of long-tail lie distributions: Seven studies from five continents. J. Commun. 74, 1–11 (2024).

Daiku, Y., Serota, K. B. & Levine, T. R. A few prolific liars in Japan: Replication and the effects of Dark Triad personality traits. PLoS ONE 16, e0249815–e0249815 (2021).

Serota, K. B., Levine, T. R. & Boster, F. J. The prevalence of lying in America: Three studies of self-reported lies. Hum. Commun. Res. 36, 2–25 (2010).

Levine, T. R. Duped: Truth-Default Theory and the Social Science of Lying and Deception (University of Alabama Press, 2020).

Ashton, M. C., Lee, K. & de Vries, R. E. The HEXACO honesty-humility, agreeableness, and emotionality factors: A review of research and theory. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 18, 139–152 (2014).

Markowitz, D. M. & Levine, T. R. It’s the situation and your disposition: A test of two honesty hypotheses. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 12, 213–224 (2021).

Levine, T. R. Examining individual differences in deception: Reported lie prevalence, truth-bias, deception detection accuracy, believability, and transparency. J. Commun. Sci. 1–21 (2022).

Ross, L., Greene, D. & House, P. The, “false consensus effect”: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 13, 279–301 (1977).

Pronin, E. Perception and misperception of bias in human judgment. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11, 37–43 (2007).

Bond, C. F. & DePaulo, B. M. Accuracy of deception judgments. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 10, 214–234 (2006).

Levine, T. R., Park, H. S. & McCornack, S. A. Accuracy in detecting truths and lies: Documenting the ‘veracity effect’. Commun. Monogr. 66, 125–144 (1999).

Levine, T. R. A few transparent liars: Explaining 54% accuracy in deception detection experiments. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 34, 41–61 (2010).

Hartwig, M. & Bond, C. F. Jr. Why do lie-catchers fail? A lens model meta-analysis of human lie judgments. Psychol. Bull. 137, 643–659 (2011).

Levine, T. R., Kim, R. K. & Hamel, L. M. People lie for a reason: Three experiments documenting the principle of veracity. Commun. Res. Rep. 27, 271–285 (2010).

Park, H. S., Levine, T. R., McCornack, S. A., Morrison, K. & Ferrara, M. How people really detect lies. Commun. Monogr. 69, 144–157 (2002).

Levine, T. R., Blair, J. P. & Clare, D. D. Diagnostic utility: Experimental demonstrations and replications of powerful question effects in high-stakes deception detection. Hum. Commun. Res. 40, 262–289 (2014).

Levine, T. R. et al. Expertise in deception detection involves actively prompting diagnostic information rather than passive behavioral observation. Hum. Commun. Res. 40, 442–462 (2014).

Levine, T. R., Shaw, A. & Shulman, H. C. Increasing deception detection accuracy with strategic questioning. Hum. Commun. Res. 36, 216–231 (2010).

Ormerod, T. C. & Dando, C. J. Finding a needle in a haystack: Toward a psychologically informed method for aviation security screening. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 144, 76–84 (2015).

Blair, J. P., Levine, T. R. & Shaw, A. S. Content in context improves deception detection accuracy. Hum. Commun. Res. 36, 423–442 (2010).

Reinhard, M.-A., Sporer, S. L. & Scharmach, M. Perceived familiarity with a judgmental situation improves lie detection ability. Swiss J. Psychol. 72, 43–52 (2013).

Hartwig, M., Granhag, P. A., Strömwall, L. A. & Kronkvist, O. Strategic use of evidence during police interviews: When training to detect deception works. Law Hum. Behav. 30, 603–619 (2006).

Levine, T. R. New and improved accuracy findings in deception detection research. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 6, 1–5 (2015).

Markowitz, D. M., Hancock, J. T., Woodworth, M. T. & Ely, M. Contextual considerations for deception production and detection in forensic interviews. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1134052 (2023).

Markowitz, D. M. & Hancock, J. T. Deception and language: The Contextual Organization of Language and Deception (COLD) framework. In The Palgrave Handbook of Deceptive Communication (ed. Docan-Morgan, T.) 193–212 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

Markowitz, D. M. The deception faucet: A metaphor to conceptualize deception and its detection. New Ideas Psychol. 59, 100816–100816 (2020).

Wright, G. R. T., Berry, C. J. & Bird, G. “You can’t kid a kidder”: Association between production and detection of deception in an interactive deception task. Front. Hum. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2012.00087 (2012).

Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2011).

Pronin, E., Gilovich, T. & Ross, L. Objectivity in the eye of the beholder: Divergent perceptions of bias in self versus others. Psychol. Rev. 111, 781–799 (2004).

Svenson, O. Are we all less risky and more skillful than our fellow drivers?. Acta Psychol. 47, 143–148 (1981).

Cross, K. P. Not can, but will college teaching be improved?. New Dir. High. Educ. 1977, 1–15 (1977).

Slovic, P., Fischhoff, B. & Lichtenstein, S. The Certainty Illusion (1976).

Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. On the psychology of prediction. Psychol. Rev. 80, 237–251 (1973).

Keren, G. Calibration and probability judgements: Conceptual and methodological issues. Acta Psychol. 77, 217–273 (1991).

Lichtenstein, S., Fischhoff, B. & Phillips, L. D. Calibration of probabilities: The state of the art to 1980. In Judgment Under Uncertainty (eds Kahneman, D. et al.) 306–334 (Cambridge University Press, 1982). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511809477.023.

DePaulo, B. M. et al. Cues to deception. Psychol. Bull. 129, 74–118 (2003).

Hauch, V., Blandón-Gitlin, I., Masip, J. & Sporer, S. L. Are computers effective lie detectors? A meta-analysis of linguistic cues to deception. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 19, 307–342 (2015).

Sporer, S. L. & Schwandt, B. Moderators of nonverbal indicators of deception: A meta-analytic synthesis. Psychol. Public Policy Law 13, 1–34 (2007).

Global Deception Research Team. A world of lies. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 37, 60–74 (2006).

Blandón-Gitlin, I., Fenn, E., Masip, J. & Yoo, A. H. Cognitive-load approaches to detect deception: Searching for cognitive mechanisms. Trends Cogn. Sci. 18, 441–444 (2014).

Buller, D. B. & Burgoon, J. K. Interpersonal deception theory. Commun. Theory 6, 203–242 (1996).

Ekman, P. & Friesen, W. V. Nonverbal leakage and clues to deception. Psychiatry 32, 88–106 (1969).

Vrij, A., Fisher, R., Mann, S. & Leal, S. A cognitive load approach to lie detection. J. Investig. Psychol. Offender Profiling 5, 39–43 (2008).

Zuckerman, M., DePaulo, B. M. & Rosenthal, R. Verbal and nonverbal communication of deception. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 14, 1–59 (1981).

Levine, T. R. & McCornack, S. A. Linking love and lies: A formal test of the McCornack and Parks Model of Deception Detection. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 9, 143–154 (1992).

McCornack, S. A. & Levine, T. R. When lovers become leery: The relationship between suspicion and accuracy in detecting deception. Commun. Monogr. 57, 219–230 (1990).

McCornack, S. A. & Parks, M. R. Deception detection and relationship development: The other side of trust. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 9, 377–389 (1986).

DePaulo, B. M., Charlton, K., Cooper, H., Lindsay, J. J. & Muhlenbruck, L. The accuracy-confidence correlation in the detection of deception. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 1, 346–357 (1997).

Levine, T. R. Deception detection and question effects: Testing truth-default theory predictions in South Korea. Hum. Commun. Res. 49, 448–451 (2023).

Levine, T. R. et al. Sender demeanor: Individual differences in sender believability have a powerful impact on deception detection judgments. Hum. Commun. Res. 37, 377–403 (2011).

Levine, T. R., Daiku, Y. & Masip, J. The number of senders and total judgments matter more than sample size in deception-detection experiments. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 17, 191–204 (2021).

Levine, T. R. NSF funded cheating tape interviews. (2007).

Ali, M. & Levine, T. R. The language of truthful and deceptive denials and confessions. Commun. Rep. 21, 82–91 (2008).

Kim, R. K. & Levine, T. R. The effect of suspicion on deception detection accuracy: Optimal level or opposing effects?. Commun. Rep. 24, 51–62 (2011).

Levine, T. R., Kim, R. K. & Blair, J. P. (In)accuracy at detecting true and false confessions and denials: An initial test of a projected motive model of veracity judgments. Hum. Commun. Res. 36, 82–102 (2010).

Levine, T. R. Truth-Default Theory (TDT): A theory of human deception and deception detection. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 33, 378–392 (2014).

Markowitz, D. M. & Hancock, J. T. Generative AI are more truth-biased than humans: A replication and extension of core truth-default theory principles. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X231220404 (2023).

Zvi, L. & Elaad, E. Correlates of narcissism, self-reported lies, and self-assessed abilities to tell and detect lies, tell truths, and believe others. J. Investig. Psychol. Offender Profiling 15, 271–286 (2018).

Halevy, R., Shalvi, S. & Verschuere, B. Being honest about dishonesty: Correlating self-reports and actual lying. Hum. Commun. Res. 40, 54–72 (2014).

Diedenhofen, B. & Musch, J. cocor: A comprehensive solution for the statistical comparison of correlations. PLoS ONE 10, e0121945–e0121945 (2015).

Levine, T. R., Serota, K. B., Carey, F. & Messer, D. Teenagers lie a lot: A further investigation into the prevalence of lying. Commun. Res. Rep. 30, 211–220 (2013).

Zheng, S. Y., Rozenkrantz, L. & Sharot, T. Poor lie detection related to an under-reliance on statistical cues and overreliance on own behaviour. Commun. Psychol. 2, 1–14 (2024).

Markowitz, D. M., Kouchaki, M., Hancock, J. T. & Gino, F. The deception spiral: Corporate obfuscation leads to perceptions of immorality and cheating behavior. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 40, 277–296 (2021).

Epley, N. Mindwise: Why We Misunderstand What Others Think, Believe, Feel, and Want (Vintage, 2015).

Clare, D. D. & Levine, T. R. Documenting the truth-default: The low frequency of spontaneous unprompted veracity assessments in deception detection. Hum. Commun. Res. 45, 286–308 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DMM is the sole author and contributed to all aspects of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Markowitz, D.M. Self and other-perceived deception detection abilities are highly correlated but unassociated with objective detection ability: Examining the detection consensus effect. Sci Rep 14, 17529 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68435-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-68435-2

- Springer Nature Limited