Abstract

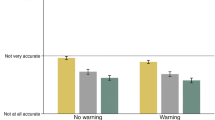

Warning labels from professional fact-checkers are one of the most widely used interventions against online misinformation. But are fact-checker warning labels effective for those who distrust fact-checkers? Here, in a first correlational study (N = 1,000), we validate a measure of trust in fact-checkers. Next, we conduct meta-analyses across 21 experiments (total N = 14,133) in which participants evaluated true and false news posts and were randomized to either see no warning labels or to see warning labels on a high proportion of the false posts. Warning labels were on average effective at reducing belief in (27.6% reduction), and sharing of (24.7% reduction), false headlines. While warning effects were smaller for participants with less trust in fact-checkers, warning labels nonetheless significantly reduced belief in (12.9% reduction), and sharing of (16.7% reduction), false news even for those most distrusting of fact-checkers. These results suggest that fact-checker warning labels are a broadly effective tool for combatting misinformation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data are available on our OSF page (https://osf.io/yux4d/).

Code availability

All analysis codes are available on our OSF page (https://osf.io/yux4d/).

References

Lazer, D. M. J. et al. The science of fake news. Science 359, 1094–1096 (2018).

Pennycook, G. & Rand, D. G. The psychology of fake news. Trends Cogn. Sci. 25, 388–402 (2021).

Kozyreva, A. et al. Toolbox of individual-level interventions against online misinformation. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8, 1044–1052 (2024).

Mosseri, A. Addressing hoaxes and fake news. Meta https://about.fb.com/news/2016/12/news-feed-fyi-addressing-hoaxes-and-fake-news/ (2016).

Instagram. Combatting misinformation on Instagram. Instagram https://about.instagram.com/blog/announcements/combatting-misinformation-on-instagram (2019).

Roth, Y. & Pickles, N. Updating our approach to misleading information. Twitter Blog https://blog.x.com/en_us/topics/product/2020/updating-our-approach-to-misleading-information (2020).

Porter, E. & Wood, T. J. Political misinformation and factual corrections on the Facebook news feed: experimental evidence. J. Polit. 84, 1812–1817 (2022).

Mena, P. Cleaning up social media: the effect of warning labels on likelihood of sharing false news on Facebook. Policy Internet 12, 165–183 (2020).

Pennycook, G., Cannon, T. D. & Rand, D. G. Prior exposure increases perceived accuracy of fake news. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 147, 1865 (2018).

Pennycook, G., Bear, A., Collins, E. T. & Rand, D. G. The implied truth effect: attaching warnings to a subset of fake news headlines increases perceived accuracy of headlines without warnings. Manag. Sci. 66, 4944–4957 (2020).

Clayton, K. et al. Real solutions for fake news? Measuring the effectiveness of general warnings and fact-check tags in reducing belief in false stories on social media. Polit. Behav. 42, 1073–1095 (2020).

Brashier, N. M., Pennycook, G., Berinsky, A. J. & Rand, D. G. Timing matters when correcting fake news. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2020043118 (2021).

Martel, C. & Rand, D. G. Misinformation warning labels are widely effective: a review of warning effects and their moderating features. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 54, 101710 (2023).

Brashier, N. M. Fighting misinformation among the most vulnerable users. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 57, 101813 (2024).

Guess, A., Nagler, J. & Tucker, J. Less than you think: prevalence and predictors of fake news dissemination on Facebook. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau4586 (2019).

Guess, A., Nyhan, B. & Reifler, J. Selective exposure to misinformation: evidence from the consumption of fake news during the 2016 US presidential campaign. European Research Council 9, 4 (2018).

Grinberg, N., Joseph, K., Friedland, L., Swire-Thompson, B. & Lazer, D. Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. presidential election. Science 363, 374–378 (2019).

Mosleh, M., Yang, Q., Zaman, T., Pennycook, G. & Rand, D. G. Unbiased misinformation policies sanction conservatives more than liberals. Preprint at https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/ay9q5 (2024).

González-Bailón, S. et al. Asymmetric ideological segregation in exposure to political news on Facebook. Science 381, 392–398 (2023).

Walker, M. & Gottfried, J. Republicans far more likely than Democrats to say fact-checkers tend to favor one side. Pew Research Center https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2019/06/27/republicans-far-more-likely-than-democrats-to-say-fact-checkers-tend-to-favor-one-side/ (2019).

Nyhan, B. & Reifler, J. Estimating fact-checking’s effects. Arlingt. VA Am. Press Inst. (2015).

Benegal, S. D. & Scruggs, L. A. Correcting misinformation about climate change: the impact of partisanship in an experimental setting. Clim. Change 148, 61–80 (2018).

Berinsky, A. J. Rumors and health care reform: experiments in political misinformation. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 47, 241–262 (2017).

Prike, T. & Ecker, U. K. Effective correction of misinformation. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 54, 101712 (2023).

Swire, B., Berinsky, A. J., Lewandowsky, S. & Ecker, U. K. H. Processing political misinformation: comprehending the Trump phenomenon. R. Soc. Open Sci. 4, 160802 (2017).

Liu, X., Qi, L., Wang, L. & Metzger, M. J. Checking the fact-checkers: the role of source type, perceived credibility, and individual differences in fact-checking effectiveness. Commun. Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/00936502231206419 (2023).

Tsfati, Y. & Cappella, J. N. Do people watch what they do not trust? Exploring the association between news media skepticism and exposure. Commun. Res. 30, 504–529 (2003).

Amazeen, M. A. & Bucy, E. P. Conferring resistance to digital disinformation: the inoculating influence of procedural news knowledge. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 63, 415–432 (2019).

Frederick, S. Cognitive reflection and decision making. J. Econ. Perspect. 19, 25–42 (2005).

Guess, A. M. & Munger, K. Digital literacy and online political behavior. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 11, 110–128 (2023).

Pennycook, G., Binnendyk, J., Newton, C. & Rand, D. G. A practical guide to doing behavioral research on fake news and misinformation. Collabra Psychol. 7, 25293 (2021).

Pennycook, G., McPhetres, J., Zhang, Y., Lu, J. G. & Rand, D. G. Fighting COVID-19 misinformation on social media: experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy-nudge intervention. Psychol. Sci. 31, 770–780 (2020).

Pennycook, G. et al. Shifting attention to accuracy can reduce misinformation online. Nature 592, 590–595 (2021).

Bhardwaj, V., Martel, C. & Rand, D. G. Examining accuracy-prompt efficacy in combination with using colored borders to differentiate news and social content online. Harv. Kennedy Sch. Misinformation Rev. 4 (2023).

Ajzen, I. & Fishbein, M. Attitude-behavior relations: a theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychol. Bull. 84, 888 (1977).

Scott, C. L. Interpersonal trust: a comparison of attitudinal and situational factors. Hum. Relat. 33, 805–812 (1980).

Önkal, D., Gönül, M. S., Goodwin, P., Thomson, M. & Öz, E. Evaluating expert advice in forecasting: users’ reactions to presumed vs. experienced credibility. Int. J. Forecast. 33, 280–297 (2017).

Sekiguchi, T. & Nakamaru, M. How intergenerational interaction affects attitude–behavior inconsistency. J. Theor. Biol. 346, 54–66 (2014).

Altay, S., Hacquin, A.-S. & Mercier, H. Why do so few people share fake news? It hurts their reputation. N. Media Soc. 24, 1303–1324 (2022).

Orchinik, R., Dubey, R., Gershman, S. J., Powell, D. & Bhui, R. Learning from and about climate scientists. Preprint at https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/ezua5 (2023).

Walter, N. & Tukachinsky, R. A meta-analytic examination of the continued influence of misinformation in the face of correction: how powerful is it, why does it happen, and how to stop it? Commun. Res. 47, 155–177 (2020).

Yaqub, W., Kakhidze, O., Brockman, M. L., Memon, N. & Patil, S. Effects of credibility indicators on social media news sharing intent. In Proc. of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 1–14 (ACM, 2020).

Pan, C. A. et al. Comparing the perceived legitimacy of content moderation processes: contractors, algorithms, expert panels, and digital juries. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 6, 1–31 (2022).

Stencel, M., Luther, J. & Ryan, E. Fact-checking census shows slower growth. Poynter https://www.poynter.org/fact-checking/2021/fact-checking-census-shows-slower-growth/ (2021).

Funke, D. Distrust in mainstream media is spilling over to fact-checking. Poynter https://www.poynter.org/fact-checking/2018/distrust-in-mainstream-media-is-spilling-over-to-fact-checking/ (2018).

Rich, T. S., Milden, I. & Wagner, M. T. Research note: Does the public support fact-checking social media? It depends who and how you ask. Harv. Kennedy Sch. Misinformation Rev. 1 (2020).

Lees, J., McCarter, A. & Sarno, D. M. Twitter’s disputed tags may be ineffective at reducing belief in fake news and only reduce intentions to share fake news among Democrats and Independents. J. Online Trust Saf. 1, 3 (2022).

Jennings, J. & Stroud, N. J. Asymmetric adjustment: partisanship and correcting misinformation on Facebook. N. Media Soc. 25, 1501–1521 (2023).

Graham, M. H. & Porter, E. Increasing demand for fact-checking. Preprint at https://osf.io/preprints/osf/wdahm (2023).

Sharevski, F., Alsaadi, R., Jachim, P. & Pieroni, E. Misinformation warnings: Twitter’s soft moderation effects on COVID-19 vaccine belief echoes. Comput. Secur. 114, 102577 (2022).

Mosleh, M., Martel, C., Eckles, D. & Rand, D. Perverse downstream consequences of debunking: being corrected by another user for posting false political news increases subsequent sharing of low quality, partisan, and toxic content in a Twitter field experiment. In Proc. of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 1–13 (ACM, 2021).

Lyons, B., Mérola, V., Reifler, J. & Stoeckel, F. How politics shape views toward fact-checking: evidence from six European countries. Int. J. Press. 25, 469–492 (2020).

Porter, E. & Wood, T. J. The global effectiveness of fact-checking: evidence from simultaneous experiments in Argentina, Nigeria, South Africa, and the United Kingdom. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2104235118 (2021).

Arechar, A. A. et al. Understanding and combatting misinformation across 16 countries on six continents. Nat. Hum. Behav. 7, 1502–1513 (2023).

Stagnaro, M. N., Druckman, J., Arechar, A. A., Willer, R. & Rand, D. Representativeness versus attentiveness: Assessing nine opt-in online survey samples. Preprint at https://osf.io/preprints/psyarxiv/h9j2d (2024).

Pennycook, G. & Rand, D. G. Fighting misinformation on social media using crowdsourced judgments of news source quality. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 2521–2526 (2019).

Allcott, H., Braghieri, L., Eichmeyer, S. & Gentzkow, M. The welfare effects of social media. Am. Econ. Rev. 110, 629–676 (2020).

Sirlin, N., Epstein, Z., Arechar, A. A. & Rand, D. G. Digital literacy is associated with more discerning accuracy judgments but not sharing intentions. Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review 2 (2021).

Berinsky, A. J., Margolis, M. F. & Sances, M. W. Separating the shirkers from the workers? Making sure respondents pay attention on self‐administered surveys. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 58, 739–753 (2014).

Rosen, G., Harbath, K., Gleicher, N. & Leathern, R. Helping to protect the 2020 US elections. Facebook Newsroom https://about.fb.com/news/2019/10/update-on-election-integrity-efforts/ (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank N. Stagnaro and A. Arechar for invaluable assistance with survey experiment data collection. We also thank B. Tappin and A. Bear for insightful comments on statistical procedures. We gratefully acknowledge funding via the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, grant number 174530. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.M. and D.G.R. designed the studies and experiments. C.M. implemented the study design, collected the data and analysed the data. C.M. drafted the paper. D.G.R. provided critical revisions. All authors approved the final paper for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Other work by D.G.R. has been funded by gifts from Meta and Google. The remaining author declares no competing interests.

Ethics and Inclusion statement

Our experimental procedures were approved by the MIT Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects (protocol numbers E-2443 and E-4195).

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Sacha Altay and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary methods, results, figures and tables.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Martel, C., Rand, D.G. Fact-checker warning labels are effective even for those who distrust fact-checkers. Nat Hum Behav (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01973-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01973-x

- Springer Nature Limited