Abstract

Social scientists from different disciplines have long argued that direct reciprocity plays an important role in regulating social interactions between unrelated individuals. Here, we examine whether 15-month-old infants (N = 160) already expect direct positive and negative reciprocity between strangers. In violation-of-expectation experiments, infants watch successive interactions between two strangers we refer to as agent1 and agent2. After agent1 acts positively toward agent2, infants are surprised if agent2 acts negatively toward agent1 in a new context. Similarly, after agent1 acts negatively toward agent2, infants are surprised if agent2 acts positively toward agent1 in a new context. Both responses are eliminated when agent2’s actions are not knowingly directed at agent1. Additional results indicate that infants view it as acceptable for agent2 either to respond in kind to agent1 or to not engage with agent1 further. By 15 months of age, infants thus already expect a modicum of reciprocity between strangers: Initial positive or negative actions are expected to set broad limits on reciprocal actions. This research adds weight to long-standing claims that direct reciprocity helps regulate interactions between unrelated individuals and, as such, is likely to depend on psychological systems that have evolved to support reciprocal reasoning and behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past two decades, investigations of early moral cognition have revealed that infants already possess sophisticated expectations about individuals’ actions in different types of social exchanges and interactions1,2. Many of these expectations echo moral norms—fairness, harm avoidance, ingroup support, and authority—that have been extensively studied in adults3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. Thus, infants expect individuals to act fairly when distributing windfall resources or allocating rewards for efforts13,14,15,16,17; they expect members of the same moral circle to avoid inflicting severe harm upon one another18,19; they expect members of the same social group to supply needed care and to display loyalty to one another20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28; and they expect leaders in a group to protect their followers, and followers to obey their leaders29,30. Our research built on these efforts in a new direction by examining whether infants might also possess an expectation of reciprocity.

Although reciprocity has long been a topic of study in the social sciences, there is relatively little consensus on how it should be defined; scholars from different disciplines have offered markedly different definitions, yielding a confusing picture31,32. Here, we built on the seminal writings of Trivers33, Gouldner34, and others35,36,37,38,39,40, which underscore the importance of direct positive and negative reciprocity in regulating social interactions among non-kin. With respect to positive reciprocity, the emphasis is typically on the initiation, development, and maintenance of equitable reciprocal partnerships between unrelated individuals. To start, agent1 may offer agent2 a gift or perform some other altruistic act toward agent2. If agent2 chooses to accept this overture of friendship and responds in kind (i.e., renders a comparable benefit), and if these altruistic interactions are repeated over time, a cooperative partnership or friendship may gradually develop that is advantageous to both agents. With respect to negative reciprocity, a similar logic applies except that the emphasis is on the return of injuries rather than benefits, and feelings of animosity rather than friendship are expected to arise across repeated negative interactions33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40.

Do infants already possess an expectation of reciprocity? To find out, we conducted violation-of-expectation experiments41 in which 15-month-old infants watched successive interactions between two women who appeared to be strangers to one another, agent1 and agent2. Our experiments examined whether initial positive or negative actions by agent1 toward agent2 would influence infants’ expectations about how agent2 might subsequently act toward agent1. In particular, would infants be surprised if agent2 chose to harm agent1 after being the beneficiary of her positive actions, or chose to help her after being the victim of her negative actions?

In line with the accounts of reciprocity described above, we speculated that one of the mechanisms underlying such judgments might be as follows. Infants might interpret positive actions by agent1 as an overture of friendship, resulting in a decrease in the social distance between the two agents and making them somewhat closer than strangers or neutral outgroups. At a minimum, such a decrease in social distance might have the consequence that moderate negative actions, which would normally be deemed acceptable toward neutral outgroups2,19,26,28,42, would no longer be viewed as such. Infants might thus be surprised if agent2, having been the beneficiary of agent1’s positive actions, chose to harm agent1. Conversely, infants might perceive negative actions by agent1 as an unprovoked act of aggression, resulting in an increase in the social distance between the two agents and making them somewhat farther apart than neutral outgroups. At a minimum, such an increase in social distance might mean that moderate positive actions, which would normally be deemed acceptable toward neutral outgroups2,22,26,28,42, would no longer be viewed as such. Infants might thus be surprised if agent2, having been the victim of agent1’s negative actions, chose to help agent1.

Our experiments also addressed two additional questions. First, would infants bring to bear an expectation of reciprocity to reason about agent2’s actions only when her actions were knowingly directed at agent1? A positive answer to this question would rule out concerns that infants simply detected low-level differences in the valences of successive actions, irrespective of their targets. Second, finding that infants detected a violation when agent2 chose to harm agent1 after being the beneficiary of her positive actions, or chose to help her after being the victim of her negative actions, would demonstrate that they possessed an expectation of reciprocity—but it would leave unclear what actions they might view as consistent with reciprocity. We speculated that infants might view a range of actions as acceptable depending on whether or not agent2 chose to engage with agent1 further, and we began to explore these possibilities.

In sum, our experiments sought to ascertain whether 15-month-old infants who observed initial positive or negative interactions between two strangers would bring to bear considerations of reciprocity when forming expectations about subsequent interactions between them.

Our tasks were informed by prior research on direct reciprocity in young children. Experiments with preschoolers have used several different types of tasks, with diverging results. While tasks with higher attentional demands43 have consistently yielded negative results with children under 5.5 years of age44,45,46,47, tasks with lower demands have produced positive results with children as young as 348,49,50,51,52,53. For example, in a costly-sharing task with 3.5-year-olds53, the child and a hand puppet (animated by an experimenter) each played with an identical toy apparatus that required tokens to operate. In critical rounds, the puppet still had eight tokens left when the child ran out; the puppet either gave away half of its remaining tokens (nice puppet) or explicitly refused to give away any tokens (mean puppet). When the tables were turned (i.e., the puppet had used up all its tokens and the child still had eight left), children who interacted with the nice puppet gave away significantly more of their tokens, gradually matching the allocations of the nice puppet across rounds. In contrast, 2.5-year-olds tested with the same task53 did not distinguish between the two puppets, leading the authors to conclude that “reciprocity begins to matter at 3.5 years of age” (p. 346). However, another possible interpretation of the negative results obtained with the 2.5-year-olds was that concern with preserving their own tokens precluded other responses.

In line with this suggestion, forced-choice tasks designed to circumvent children’s self-interest have yielded positive results with infants54,55,56,57. Two types of forced-choice tasks have been used, first- and third-party tasks. In first-party tasks, infants themselves are the recipients of positive and negative actions by two protagonists. In one such task54, 21-month-olds faced two women, one who gave them toys (nice woman) and one who offered them toys but teasingly took them back (mean woman). Next, the two women were offered a toy that fell out of their reach but within infants’ reach. Infants were significantly more likely to return the toy to the nice as opposed to the mean woman, and the same result was found even if the nice woman attempted but failed to give infants toys. In third-party tasks, another individual is the recipient of the protagonists’ positive and negative actions. In one such task involving geometric shapes with eyes55,56,57, 10−16-month-olds watched a climber try unsuccessfully to reach the top of a steep hill. On alternate trials, it was helped to the top of the hill by one character (nice character) or knocked down to the bottom of the hill by another character (mean character). Next, in the test trials, the hill was removed, and the climber stood between the two characters. Infants expected the climber to approach the nice character, and they were surprised if it approached the mean character instead.

For present purposes, one limitation of the preceding findings with preschoolers and infants is that they cannot tell us whether young children expect others to act in accordance with reciprocity. Across repeated rounds in costly-sharing tasks, children might come to match the positive actions of a nice puppet for a variety of reasons, without holding a general expectation of reciprocity. Similarly, forced-choice tasks indicate which of two protagonists children view as the more fitting target for a positive or affiliative action, but they do not reveal how children expect individuals to act when responding to others’ actions. These considerations suggested that assessing whether infants possess an expectation of reciprocity required tasks that more directly explored what actions infants would deem acceptable following a protagonist’s positive or negative actions. The present research introduced such tasks.

In violation-of-expectation experiments depicting interactions between two strangers, agent1 and agent2, we first show that 15-month-old infants look about equally whether agent1 directs a moderately positive or negative action toward agent2; in line with prior work, both actions are deemed acceptable toward a stranger. Nevertheless, infants do expect the two actions to have distinct consequences for the agents’ subsequent interactions, in accordance with reciprocity. Thus, after agent1 acts positively toward agent2, infants are surprised if agent2 chooses to act negatively toward agent1 in a new context. Similarly, after agent1 acts negatively toward agent2, infants are surprised if agent2 chooses to act positively toward agent1 in a new context. Both responses are eliminated when agent2’s actions are not knowingly directed at agent1 (because they are directed at a new agent, or because agent2 does not know she is acting on agent1’s possessions). Finally, we find that infants view a range of actions by agent2 as consistent with reciprocity: They find it acceptable for agent2 either to respond in kind to agent1 or to not engage with her further. By 15 months of age, infants thus already expect a modicum of reciprocity between strangers: Initial positive or negative actions are expected to set broad limits on reciprocal actions.

Results

Experiment 1

In Experiment 1, we created scenarios in which agent1 acted either positively or negatively toward agent2. In designing these scenarios, we built on prior evidence, alluded to earlier, that infants typically view both moderate positive actions (e.g., giving, helping) and moderate negative actions (e.g., stealing, hindering, knocking down a tower, crumpling a drawing) as acceptable toward non-ingroup members19,26,28,42,57. By contrast, negative actions are generally deemed unacceptable toward ingroup members, as they violate expectations of ingroup support19,22,23,28,58.

Infants in a baseline group (N = 40) were randomly assigned to a give or a steal condition. In the give condition, agent1 gave agent2 cookies; in the steal condition, she stole agent2’s cookies (Fig. 1). The two agents wore different shirts and presented no particular cues that they belonged to the same social group, so they were expected to be viewed, at least initially, as strangers or neutral outgroups20,22,28. We reasoned that finding equal looking times in the give and steal conditions would provide evidence that infants (a) identified agent1 and agent2 as neutral outgroups and (b) perceived both the positive and the negative actions of agent1 toward agent2 as acceptable, in line with prior findings. Such a looking pattern was essential to ground our exploration, in subsequent experiments, of infants’ expectation of reciprocity: Broadly speaking, any deviation from this pattern, with infants looking significantly longer at either event, would make it difficult to isolate the contribution of reciprocity to infants’ interpretation of agent2’s actions toward agent1.

Infants faced a puppet-stage apparatus and received three identical familiarization trials. In the give condition, agent2 initially sat alone at a window in the back wall of the apparatus. After a brief pause, agent1 opened a curtained window in the right wall, brought in a plate with two cookies, and said, “My cookies!” Next, she gave one of her cookies to agent2, who had none. The two agents ate their cookies and then agent1 left, closing her window as she went. In the steal condition, each agent had a cookie and said, “My cookie!” in turn. Next, agent1 grabbed agent2’s cookie and then stuffed it in her mouth and left with her own cookie. After agent1 left in each trial, agent2 looked down and paused, and infants saw this paused scene until the trial ended.

Infants received three familiarization trials. At the start of each trial in the give condition, agent2 sat alone at a window in the back wall of a puppet-stage apparatus, with an empty plate in front of her. After a brief pause, agent1 opened a curtained window in the right wall of the apparatus. She brought in a plate with two mini-Oreo cookies, deposited the plate on the apparatus floor, and told agent2, “My cookies!” Next, agent1 placed one cookie on agent2’s plate, the two agents ate their cookies, and then agent1 left with her empty plate, closing her window as she went. Agent2 then looked down and paused until the trial ended (see Procedure in Methods for criteria used to end trials). In the steal condition, each agent had a cookie and said, “My cookie!” in turn. Next, agent1 grabbed agent2’s cookie and then stuffed it in her mouth and left with her own cookie.

Infants’ looking times at the paused end scenes of the three familiarization trials were averaged and analyzed using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) with condition (give, steal) as a between-subjects factor (Fig. 2). The main effect of condition was not statistically significant, F(1, 38) = 0.016, p = 0.899, \({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}\) = 0.000, 90% confidence interval (CI) = [0.000, 0.034] (all tests were two-tailed, with α set at 0.05; for descriptive statistics, see Supplementary Table 1). A non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test confirmed this result, Z = 0.162, p = 0.871. In addition, a Bayes Factor (BF) test comparing the two conditions, using the default Cauchy prior (scale = 0.707), yielded a BF of 3.22 in favor of the null hypothesis (according to conventional cut-offs, a BF factor of 3 − 10 is considered moderate support for a hypothesis59,60). Similar ANOVA results were obtained for the inconsistent, control, and consistent groups tested in Experiments 2 and 3, who received the same familiarization trials, all three Fs(1, 38) ≤ 1.061, ps ≥ 0.309, \({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}{\rm{s}}\) ≤ 0.027, 90% CI for the largest \({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}\) = [0.000, 0.152]. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests again confirmed these results, all Zs ≤ 0.433, ps ≥ 0.665. Finally, a BF test combining all four groups (N = 160, 80 per condition) yielded a BF of 5.67 in favor of the null hypothesis.

Dots represent means, and error bars represent standard errors. In each violin plot, the width of the shaded area represents the proportion of looking times observed at each value, smoothed by a kernel density estimator. Overlaid on each violin plot is a boxplot ranging from the 25th to the 75th percentile, with a line drawn at the median. All violin plots in this article were produced using R version 4.3.1 and Adobe Illustrator version CS3.

These results provided no credible evidence that infants responded differently when agent1 gave cookies to agent2 or stole cookies from her. As such, they ensured that we had a sound, even platform from which to assess the contribution of reciprocity to infants’ expectations about agent2’s response to agent1; findings of divergent expectations following agent1’s positive and negative actions could not be attributed to infants’ differential reactions to these actions alone.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 examined whether infants would detect a reciprocity violation if agent2 chose to harm agent1 after being the beneficiary of her positive actions, or chose to help her after being the victim of her negative actions. Infants (N = 80) were assigned to an inconsistent or a control group.

Infants in the inconsistent group were assigned to a give or a steal condition, and they first received the three familiarization trials appropriate for their condition, as in Experiment 1. Next, they received a test trial whose final outcome was inconsistent with reciprocity, given the events shown in the familiarization trials. At the start of the test trial, agent1 faced a stack of three colorful stickers and a stack of three yellow papers. While agent2 watched, agent1 selected the top sticker, removed its transparent backing, and affixed it to the top paper. Next, she picked up her newly decorated paper and briefly admired it before storing it in an open treasure box to the left of her window. She then repeated these actions with the two remaining stickers. While she was admiring her third and last decorated paper, a bell rang. Agent1 then deposited her paper on the apparatus floor, said, “Oh, I have to go, I’ll be back!”, and left. Next, Agent2 picked up the paper, and what she did with it differed between the two conditions. In the give condition, she tore the paper into four pieces, dropped them onto the apparatus floor, and then looked down and paused (Fig. 3). In the steal condition, she helpfully stored the paper into the box, thus completing the action sequence agent1 had been performing when she was called away; agent2 then looked down and paused (Fig. 4). In each condition, infants thus saw an outcome inconsistent with reciprocity.

Infants received the same three familiarization trials as in the give condition of the baseline group in Experiment 1, followed by a single test trial. In the inconsistent group, agent1 initially faced a stack of three colorful stickers and a stack of three yellow papers. While agent2 watched, agent1 selected the top sticker, removed its transparent backing, and affixed it to the top paper. Next, she picked up her newly decorated paper and briefly admired it before storing it in an open treasure box to the left of her window. She then repeated these actions with the two remaining stickers. While she was admiring her third and last decorated paper, a bell rang. Agent1 then deposited her paper on the apparatus floor, said, “Oh, I have to go, I’ll be back!”, and left. Next, Agent2 picked up the paper, tore it into four pieces, dropped the pieces onto the apparatus floor, and then looked down and paused. Infants thus saw an action that violated reciprocity. In the control condition, the initial portion of the trial was modified so that agent2’s action no longer violated reciprocity. For half of the infants (new-agent subgroup), agent1 was replaced with agent3; for the other infants (no-knowledge subgroup), agent2 arrived after agent1 had left and thus did not know that the toys on the apparatus floor belonged to agent1. In each subgroup, the trial again ended with agent2 tearing up the decorated paper left on the apparatus floor and then pausing. The test trial was always preceded by a brief pretest trial (not shown) in which agent1/agent3 sat alone (agent2’s window was closed) and prepared and stored two additional papers.

Infants received the same three familiarization trials as in the steal condition of the baseline group in Experiment 1, followed by a single test trial. For infants in the inconsistent group and in the new-agent and no-knowledge subgroups of the control group, this trial was identical to that shown in the give condition (Fig. 3), except that at the end of the trial agent2 stored the decorated paper left on the apparatus floor into the box and then paused. This test trial again violated reciprocity in the inconsistent group, but not in the control group. The test trial was always preceded by a brief pretest trial (not shown) in which agent1/agent3 sat alone (agent2’s window was closed) and prepared and stored two additional papers.

The control group was designed to address concerns that infants in the inconsistent group might simply detect low-level differences in the valences of the actions shown in the familiarization and test trials, irrespective of their targets. Trials in the control group were identical to those in the inconsistent group except that, in each condition, the initial portion of the test trial was modified so that considerations of reciprocity no longer applied. Two different modifications were used, for greater experimental control. For half of the infants, a new agent, agent3, replaced agent1 in the test trial (new-agent subgroup). For the other infants, agent2 did not enter the apparatus until agent1 had been called away, so that agent2 had no knowledge that the decorated paper and the box belonged to agent1 (no-knowledge subgroup). This second modification was suggested by prior evidence that when observing social interactions, infants take into account what agents know when evaluating their actions16,28,61,62,63 (e.g., although infants generally expect rewards to be commensurate with efforts, they view it as acceptable for an individual who assigned a task to two workers and does not know that one did all the work to reward both equally16). In the new-agent subgroup, reciprocity did not apply because agent2’s actions were directed at agent3, instead of agent1; to infants, tearing up agent3’s paper or helpfully storing it for her would both seem acceptable, as moderate negative and positive actions are typically viewed as acceptable toward neutral outgroups. In the no-knowledge subgroup, reciprocity did not apply because agent2 did not know that the paper and the box she found on the apparatus floor belonged to agent1, so that her actions were not knowingly directed at agent1; tearing up or storing the paper were simply two possible actions agent2 could perform with these toys.

We reasoned that if by 15 months infants (a) expect at least some degree of positive and negative reciprocity in an interaction between two strangers, but also (b) recognize that a reciprocal action can be appropriately targeted only at the protagonist who initiated the interaction, and only at items knowingly associated with this protagonist, then two predictions followed. In the inconsistent group, infants in both conditions should view the test outcomes they were shown as surprising: In the give condition, infants should be surprised that agent2 chose to harm agent1 (by tearing up her paper) after being repeatedly given a treat by her; and in the steal condition, they should be surprised that agent2 chose to help agent1 (by storing her paper for her) after being repeatedly robbed by her. In the control group, in contrast, infants in the two conditions should not view the test outcomes they were shown as surprising: The paper and the box either belonged to agent3 or were not clearly identified as belonging to agent1, so that considerations of reciprocity did not apply, making it acceptable for agent2 to either tear up the paper or store it in the box. In sum, we predicted that infants in the inconsistent group would look significantly longer at the test outcomes they were shown than infants in the control group, and that this looking pattern would be found in both the give and the steal conditions.

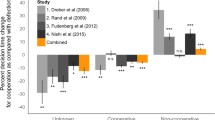

In a first analysis, infants’ test looking times in the two control subgroups were examined using an ANOVA with subgroup (new-agent, no-knowledge) and condition (give, steal) as between-subjects factors. There were no statistically significant effects, all Fs(1, 36) ≤ 0.171, ps ≥ 0.682, \({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}{\rm{s}}\) ≤ 0.005, 90% CI for the largest \({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}\) = [0.000, 0.094]. In addition, when comparing the two subgroups, a Wilcoxon rank-sum test revealed no statistically significant difference, Z = 0.217, p = 0.829, and a BF test yielded a BF of 3.13 in favor of the null hypothesis. Thus, as expected, comparison of the two subgroups yielded no credible evidence that infants responded differently when agent2 acted on agent3’s toys or on toys not clearly belonging to agent1. Next, the two subgroups were pooled, and test looking times in the control group as a whole were compared to those in the inconsistent group using an ANOVA with group (inconsistent, control) and condition (give, steal) as between-subjects factors (Fig. 5). The only statistically significant effect was the main effect of group, F(1, 76) = 23.550, p < 0.001 \({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}\) = 0.237, 90% CI = [0.108, 0.359], with infants in the inconsistent group looking significantly longer than those in the control group. Planned comparisons confirmed that this result held separately in the give condition, F(1, 76) = 11.320, p = 0.001, \({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}\) = 0.130, 90% CI = [0.034, 0.247], and the steal condition, F(1, 76) = 12.239, p = 0.001, \({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}\) = 0.139, 90% CI = [0.039, 0.257]. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests confirmed the group effect observed in the two conditions combined, Z = 4.203, p < 0.001, in the give condition, Z = 2.856, p = 0.004, and in the steal condition, Z = 2.991, p = 0.003.

a Overall looking times in the inconsistent group of Experiment 2 (yellow violin plot), the control group of Experiment 2 (blue), and the consistent group of Experiment 3 (beige; N = 40 per plot). b Looking times in the same groups shown separately for the give condition (N = 20 per plot). c Looking times in the same groups shown separately for the steal condition (N = 20 per plot). Dots represent means, and error bars represent standard errors. In each violin plot, the width of the shaded area represents the proportion of looking times observed at each value, smoothed by a kernel density estimator. Overlaid on each violin plot is a boxplot ranging from the 25th to the 75th percentile, with a line drawn at the median.

The results of Experiment 2 supported three conclusions. First, they indicated that by 15 months of age, infants already possess an expectation of reciprocity. Following agent1’s positive actions toward agent2, infants in the inconsistent group were surprised if agent2 chose to act negatively toward agent1; following agent1’s negative actions, they were surprised if agent2 chose to act positively toward agent1. This response pattern could not be attributed to a low-level, novelty-based tendency to look longer when positive actions were followed by a negative one, or when negative actions were followed by a positive one: Infants in the control group saw identical outcomes yet showed no novelty response. Second, infants selectively and appropriately applied their expectation of reciprocity. It was only when agent2 knowingly acted on agent1’s belongings that infants brought to bear considerations of reciprocity to interpret agent2’s actions. When these actions were directed at agent3 (new-agent subgroup), or when agent2 did not know she was acting on toys belonging to agent1 (no-knowledge subgroup), infants gave no evidence that they considered reciprocity. Finally, infants in the inconsistent group successfully detected the reciprocity violations in agent2’s actions even though these actions occurred only once and in a different context than agent1’s actions, hinting at both the immediacy and the abstractness of infants’ expectation of reciprocity.

Experiment 3

In Experiment 2, infants viewed agent2’s decision to harm agent1 after receiving a treat from her, or to help her after being robbed by her, as inconsistent with reciprocity. What actions by agent2 might infants view as consistent with reciprocity? Experiment 3 began to examine this question.

Infants in a consistent group (N = 40) were assigned to a give or a steal condition, and they first received the same familiarization trials as in Experiments 1 and 2, followed by a test trial similar to that in Experiment 2. We speculated that infants in each condition might view a range of actions by agent2 as consistent with reciprocity, depending on whether or not she chose to engage with agent1 further (after all, the two agents were strangers interacting in an unfamiliar situation, and agent2 might decide, for a variety of reasons, not to pursue this interaction). If agent2 chose to engage with agent1 further, she might respond to her in kind: help her after being the beneficiary of her positive actions, and harm her after being the victim of her negative actions. Conversely, if agent2 chose not to engage with agent1 further, she might act more neutrally: not help her following her positive actions, and not harm her following her negative actions.

In line with these two broad possibilities, infants in each condition were assigned to one of two subgroups. In one, agent2 opted to engage with agent1 further and responded in kind to her actions (in-kind subgroup). Thus, in the give condition, agent2 helpfully stored agent1’s last decorated paper, and in the steal condition, she tore it up and dropped the pieces on the apparatus floor (Supplementary Fig. 1). Infants in this subgroup thus saw the opposite outcomes from those shown in the give and steal conditions of the inconsistent group in Experiment 2. In the other subgroup, agent2 chose not to engage with agent1 further (no-engagement subgroup). To make clear agent2’s lack of engagement, the experimental setup of the test trial was modified slightly. While agent2 watched, agent1 first decorated two papers with stickers, as usual. However, her last decorated paper, already prepared, now lay across the apparatus, out of her reach but within agent2’s reach22,28; agent1 tried unsuccessfully to grasp it until she was called away by the bell. After she left, in both the give and steal conditions, agent2 picked up the paper, examined it, and then returned it to its original position on the apparatus floor, out of agent1’s reach (Supplementary Fig. 2). Thus, in both conditions, agent2 chose not to engage with agent1 further: not to help her by bringing her paper closer or storing it in the give condition, and not to harm her by stealing or destroying her paper in the steal condition.

If we were right in supposing that infants in the in-kind and no-engagement subgroups of each condition would view agent2’s actions as acceptable and broadly consistent with reciprocity, then several predictions followed: In both conditions, infants in the two subgroups should respond similarly, and with little or no surprise, to the test outcomes they were shown; the responses of the consistent group as a whole should differ significantly from those of the inconsistent group in Experiment 2; and this last pattern should hold separately in the give and steal conditions.

In the first analysis, infants’ test looking times in the two consistent subgroups were examined using an ANOVA with subgroup (in-kind, no-engagement) and condition (give, steal) as between-subjects factors. There were no statistically significant effects, all Fs(1, 36) ≤ 0.604, ps ≥ 0.442, \({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}{\rm{s}}\) ≤0.017, 90% CI for the largest \({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}\) = [0.000, 0.133]. In addition, when comparing the two subgroups, a Wilcoxon rank-sum test revealed no statistically significant difference, Z = 0.135, p = 0.892, and a BF test yielded a BF of 3.01 in favor of the null hypothesis. Thus, as expected, a comparison of the two subgroups yielded no credible evidence that infants responded differently when agent2 chose to respond in kind to agent1 or to not engage with her further. Next, the two subgroups were pooled, and test responses in the consistent group as a whole were compared to those of the inconsistent group in Experiment 2 using an ANOVA with group (inconsistent, consistent) and condition (give, steal) as between-subjects factors (Fig. 5). The only statically significant effect was that of group, F(1, 76) = 37.446, p < 0.001, \({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}\) = 0.330, 90% CI = [0.189, 0.447], with infants in the inconsistent group looking significantly longer than those in the consistent group. Planned comparisons revealed that this result held separately in the give condition, F(1, 76) = 19.891, p < 0.001, \({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}\) = 0.207, 90% CI = [0.085, 0.330], and the steal condition, F(1, 76) = 17.591, p < 0.001, \({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}\) = 0.188, 90% CI = [0.071, 0.310]. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests confirmed the group effect observed in the two conditions combined, Z = 5.088, p < 0.001, in the give condition, Z = 3.694, p < 0.001, and in the steal condition, Z = 3.505, p < 0.001 (for an overall analysis of the test data in Experiments 2 and 3, see Supplementary Methods; for online surveys with adults used as manipulations checks for the events shown in Experiments 1 − 3, see Methods and Supplementary Note 1).

Experiment 3 thus extended Experiment 2 by providing a more complete picture of how infants reason about reciprocity. Following agent1’s positive or negative actions toward agent2, infants viewed it as acceptable for agent2 either to respond in kind to her or to not engage with her further; in each case, infants could generate an explanation for agent2’s actions. Together, Experiments 2 and 3 thus demonstrate that when watching two strangers interact, infants do not necessarily expect initial actions by agent1 to be met with actions of equal valence and magnitude by agent2. Infants do bring to bear an expectation of reciprocity: Moderate positive actions by agent1 are expected to lead agent2 to refrain from directing moderate negative actions toward her, and moderate negative actions by agent1 are expected to lead agent2 to refrain from directing moderate positive actions toward her. Still, infants do not hold particular expectations about how far agent2 should go in matching the exact value of agent1’s actions, at least in the minimal interactive context studied here. To paraphrase the oft-cited description of reciprocity found in the 13th century Icelandic literary work the Edda, our results indicate that rather than expecting strangers “to meet smiles with smiles and lies with treachery”, infants simply expect smiles not to be met with treachery, or lies with smiles.

Discussion

Our experiments demonstrate that by 15 months of age, considerations of direct reciprocity already modulate infants’ expectations about social interactions between strangers. After agent1 acted positively toward agent2, infants no longer viewed it as acceptable for agent2 to harm agent1. As we speculated in the Introduction, this result suggests that infants interpreted agent1’s actions as a friendly overture that somewhat decreased the social distance between the two agents. As a result, negative actions normally deemed acceptable toward a neutral outgroup became unacceptable. Conversely, after agent1 acted negatively toward agent2, infants no longer viewed it as acceptable for agent2 to help agent1. This result suggests that infants interpreted agent1’s actions as an unprovoked act of aggression that somewhat increased the social distance between them, rendering positive actions normally deemed acceptable toward a neutral outgroup unacceptable. Importantly, these response patterns were obtained only when agent2’s actions were knowingly directed at agent1: They were eliminated when agent2’s actions were directed at a new agent or at items agent2 did not know belonged to agent1.

These results echo prior findings that 29- and 13-month-olds expect indirect reciprocity, or third-party punishment, following harm to an ingroup victim28. In violation-of-expectation experiments, children watched events involving three agents: a bystander, a wrongdoer, and a victim. Group memberships were manipulated across experiments and were marked by novel labels or outfits. While the bystander watched, the wrongdoer stole a toy from the victim; next, the wrongdoer needed help to complete a task because a relevant item lay out of her reach, but within the bystander’s reach. When the bystander and the victim belonged to one group and the wrongdoer to a different group, children looked significantly longer if the bystander helped the wrongdoer (by bringing the item closer) as opposed to harmed the wrongdoer (by discarding the item). In contrast, across ages and experiments, children looked equally at the two outcomes if the bystander had no knowledge of the theft, if the victim belonged to the same group as the wrongdoer instead of the bystander, or if group memberships were not marked. Thus, it was only when the bystander knowingly experienced an injury to her ingroup, and by extension to herself, that infants brought to bear considerations of reciprocity: The outgroup wrongdoer’s negative action increased the social distance between the two groups, rendering positive actions toward her unacceptable (for a review of additional research on early third-party punishment of harm and fairness transgressions in ingroup and non-ingroup interactions, see ref. 28).

Although infants detected a reciprocity violation when agent2 chose to harm agent1 after being the beneficiary of her positive actions, they looked equally whether she chose to respond in kind to agent1’s friendly overture or to not engage with her further. This result suggests that infants perceived both actions to be broadly consistent with reciprocity and dovetails well with reciprocity accounts that emphasize partner choice64,65,66,67,68, as opposed to partner control. Just as agent1 had a choice in approaching agent2 as a potential partner and might move on to a different partner if rebuffed, agent2 had a choice in whether or not to embark on a reciprocal partnership with agent1. In the infancy literature, there is extensive evidence that infants construe personal preferences as subjective and individual-specific69,70,71: For example, they understand that the fact that agent1 prefers stuffed animals over balls provides no information about whether agent2 will have a preference for either of these toy categories. In a similar vein, infants in our experiments appreciated that although agent1 might be trying to make friends with agent2, agent2 might or might not want to become friends with her, and they viewed actions by agent2 that befit either possibility as acceptable.

Likewise, although infants detected a reciprocity violation when agent2 chose to help agent1 after being the victim of her negative actions, they looked equally whether she chose to respond in kind to agent1’s act of aggression, by countering it with one of her own, or chose to not engage with agent1 further. This result again suggests that infants viewed both actions to be broadly consistent with reciprocity. Agent2 might want to retaliate against agent1 and stoke their nascent antagonism, or she might opt to not add fuel to it, and infants viewed actions that befit either possibility as acceptable.

Together, our results indicate that infants expect a modicum of reciprocity between strangers. Initial moderate positive or negative actions are expected not to be met with reciprocal moderate actions of opposite valence: Smiles should not be met with treachery, or lies with smiles. Beyond this, however, infants hold no particular expectations about how far reciprocal actions should go in matching the exact value of initial actions. Initial positive actions by agent1 toward agent2 will bring the two closer than neutral outgroups—but how much closer remains to be seen. Likewise, initial negative actions by agent1 toward agent2 will move the two farther apart than neutral outgroups—but how much farther will depend on a variety of factors.

Our findings dovetail with prior results showing that by about 3 years of age, children not only expect others to exhibit direct positive and negative reciprocity but do so themselves, in a variety of contexts48,49,50,51,52,53. For example, preschool children were more likely to share their tokens for a game when paired with a nice puppet who had previously shared its tokens with them than when paired with a mean puppet who had refused to do so53; they were more likely to return a toy fallen out of reach to a nice puppet who had given them needed information for solving a task than to a mean puppet who had refused to do so48; they were more likely to ask for items from one of two toy animals to whom they had given more stickers50; and they directed a protagonist to give more items to dolls who had given pennies to the protagonist than to dolls who had either kept their pennies or given them to someone else49.

However, our findings and those summarized above contrast with other results suggesting that although children exhibit direct negative reciprocity by at least 4 years of age, they do not exhibit direct positive reciprocity until several years later72. To illustrate this latter result, in an experiment with 4- to 5-year-olds, each child played a computer game with four confederates who were represented by animal avatars and were described as unfamiliar children playing the game remotely. There were four trials, with new confederates introduced in each trial. In the first half of each trial, the confederates each received a sticker, and one confederate voluntarily gave its sticker to the child, who had received none. In the second half, the child received a sticker, but the confederates did not. When told to give their sticker to one of the confederates, children were no more likely to give it to their benefactor than to any other confederate (memory checks confirmed that children remembered who their benefactor was). In another experiment, children were given the option of either keeping their sticker or giving it to one of the confederates. Only about half of the children gave away their sticker, and those who did again selected a confederate at random. In yet another experiment with 4- to 9-year-olds, children received two trials designed to tap their understanding of (as opposed to their ability to exhibit) direct positive reciprocity. In one trial, children first received a sticker from one of the confederates and then were asked to which confederate they should now give a sticker. In the other trial, children first gave a sticker to one of the confederates and then were asked which confederate should now give them a sticker. Strikingly, children did not select their benefactor or their beneficiary at above-chance levels until about 7 years of age. The authors concluded that prior to that age, “children do not seem to know that they should return a favor to the same person who benefited them previously, and they do not even expect positive reciprocity from a person they had just rewarded” (p. 12).

However, other interpretations are possible. One is that the anonymous, minimal interactions that took place between children and confederates in the experiments were too limited to elicit considerations of direct positive reciprocity. As children and confederates never met in person nor knew each other’s identity, and confederates varied from trial to trial, there was little reason for children to construe a benefactor’s gift as a potential overture of friendship. Another interpretation, consistent with the present research, is that children tended to view a benefactor’s gift as requiring only a modicum of reciprocity, which the measures used could not detect. In this view, even though children felt no compunction to respond in kind to a benefactor’s gift, they could still have balked at harming the benefactor. One way to evaluate this interpretation would be to test whether children would be less likely, when told to steal one of the confederates’ stickers, to select that of a benefactor. Positive results would suggest that in the context of these anonymous, minimal interactions, children felt compelled not to harm their benefactors, even if they chose not to engage with them further.

Future research can build on our findings in several directions. One would be to confirm the results of our inconsistent and consistent groups using new positive and negative actions similar to those used here (e.g., agent1 might first give or steal goldfish crackers and then need help opening a box containing a desired toy26,42). Another direction would be to confirm the results of our control group using a new, non-evaluative manipulation in which infants did not see giving or stealing actions in the familiarization trials. For example, infants could be tested using the same procedure as in the inconsistent group except that the start of each familiarization trial would be modified. In the modified-give condition, agent2 would have a cookie, agent1 would bring in a cookie, each agent would eat her cookie, and then agent1 would leave as before; in the modified-steal condition, agent2 would have no cookie, and agent1 would bring in two cookies, place one in her mouth, and then leave with her remaining cookie as before. We would expect infants to show little or no surprise in the test trial when agent2 harmed (modified-give condition) or helped (modified-steal condition) agent1: As the familiarization trials did nothing to alter the social distance between the two agents, both actions should still be viewed as acceptable.

Other research directions could address new questions about early reciprocity. First, would infants be more likely to expect in-kind responding or exact reciprocity if agent1’s positive actions involved greater costs to herself and greater benefits to agent2? In our experiments, agent1 offered simple gifts that were neither needed nor requested by agent2. What if instead agent2 needed critical help to complete a task, agent1 provided it at a substantial cost to herself, and the roles were then reversed, with agent1 now needing help? Evidence that infants expected in-kind responding would suggest that from a young age, infants’ expectation of reciprocity is sufficiently sophisticated to take into account meaningful conceptual variation (e.g., a small, unnecessary gift creates a weaker obligation to reciprocate than does costly critical assistance).

Second, how would infants’ expectation of reciprocity interact with their expectations of ingroup support19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 and authority29,30? For example, following agent1’s negative actions, would infants expect agent2 (a) to retaliate less if the two agents were members of the same group, and (b) to retaliate even less, or not at all, if agent1 was a leader of the group?

Third, additional research could explore how infants’ expectation of reciprocity changes with age and experience. When adult participants read scenarios adapted from those we showed infants (see Supplementary Note 1), their ratings of agent2’s actions were generally in line with infants’ responses (e.g., harming agent1 after receiving a cookie from her, and helping agent1 after being robbed of a cookie by her, were both rated as implausible scenarios), with one exception. When agent1 gave agent2 a cookie and later needed help with a simple task, adults rated a decision not to help her as less plausible than a decision to help her, whereas infants seemed to view both decisions as equally plausible. One explanation for this age difference could be that when judging what actions are acceptable following an overture of friendship that one has no desire to pursue, infants view only moderate negative actions as unacceptable, whereas adults also tend to view mild negative actions as less than ideal, particularly when the costs associated with more positive courses of action are fairly minimal. In our adult scenarios, the actions needed to help agent1 (e.g., picking up her fallen sticker and moving it closer to her sticker book) were so trivial and required so little effort that to adults, agent2’s decision not to produce them may have bordered on churlishness (for additional discussion, see Supplementary Note 1).

Finally, research is also needed to explore how infants’ expectation of reciprocity comes to guide their own interactions with siblings and peers, and how parental, social, and cultural factors help shape these interactions73,74,75.

In sum, our research demonstrates that by 15 months of age, infants already expect a modicum of reciprocity between strangers. Our findings add weight to long-standing claims that direct reciprocity helps regulate social interactions between unrelated individuals and, as such, is likely to depend on psychological systems that have evolved to support reciprocal reasoning and behavior33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,64,65,66,67,68.

Methods

The protocols used in Experiments 1−3 were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and each infant’s parent gave written informed consent prior to the testing session.

Power analysis

Experiments 2 and 3 reported primary and secondary analyses using ANOVAs with 2 × 2 between-subjects designs. The primary analyses were group × condition analyses, comparing the give and steal conditions in the inconsistent and control groups (Experiment 2) and in the inconsistent and consistent groups (Experiment 3). The secondary analyses were subgroup × condition analyses, comparing the give and steal conditions in the new-agent and no-knowledge subgroups of the control group (Experiment 2) and in the in-kind and no-engagement subgroups of the consistent group (Experiment 3). These secondary analyses were necessary to allow the subgroups (which were expected to yield identical responses in each experiment) to be combined for the primary analyses comparing groups. For our power analysis, we relied on previous experiments by Jin and Baillargeon22 that examined sociomoral reasoning in 17-month-old infants using the violation-of-expectation method, live events, and 2 × 2 between-subjects ANOVAs. The average interaction effect size (\({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}\)) in their experiments was 0.19. A power analysis using G*Power version 3.176 based on this value indicated that, with power set at 0.80 and α set at 0.05, the minimum number of participants required per subgroup × condition cell was nine participants. In line with this analysis, we tested 10 participants in each subgroup × condition cell, resulting in 40 participants each in the control and consistent groups. We similarly tested 40 participants each in the baseline group of Experiment 1 and the inconsistent group of Experiment 2. This resulted in a total of 160 participants across all three experiments, with 40 participants per group and 20 participants per group × condition cell.

Participants

Participants in Experiments 1−3 were 160 healthy, term 15-month-old infants (83 male, M = 15 months, 22 days; range: 15 months, 3 days to 16 months, 16 days). Forty infants were randomly assigned to each of four groups: the baseline group (22 male, M = 15 months, 22 days; Experiment 1), the inconsistent group (21 male, M = 15 months, 21 days; Experiment 2), the control group (20 male, M = 15 months, 24 days; Experiment 2), and the consistent group (20 male, M = 15 months, 21 days; Experiment 3). Data collection in all four groups overlapped. The control group was evenly divided into two subgroups (new-agent, no-knowledge), as was the consistent group (in-kind, no-engagement); in each group, the two subgroups saw experimental manipulations that were expected to have and did have identical effects. Within each group (and subgroup, where applicable), half of the infants were randomly assigned to the give condition, and half to the steal condition. Another 25 infants were tested but excluded: 16 were distracted (6), fussy (5), inattentive (3), or drowsy (2); 1 was the subject of parental interference; 1 was uninterested and crawled away; and 7 (3 in the control group and 4 in the consistent group) had a test looking time over 2.5 standard deviations from the group mean.

In each experiment, infants’ names were obtained from a university-maintained database of parents interested in participating in child development research. Parents received a child’s gift or travel reimbursement as compensation for their participation.

Apparatus

The apparatus consisted of a brightly lit puppet-stage apparatus (201 cm high × 102 cm wide × 57 cm deep) with a large opening (46 cm × 95 cm) in its front wall; between trials, a supervisor lowered a curtain in front of this opening. Inside the apparatus, the walls were white, and the floor was covered with pastel adhesive paper. Up to three female experimenters worked together to produce the events shown to infants. Agent2 wore a green shirt and sat at a window (50 cm × 50 cm) in the back wall of the apparatus; this window could be closed with two identical white doors. Agent1 wore a blue shirt and knelt at a window (51 cm × 38 cm) in the right wall of the apparatus; this window could be closed with a sliding white curtain. In the control new-agent subgroup, agent1 was replaced in the pretest and test trials by agent3, who wore a gray shirt. As an event unfolded, the experimenters never made eye contact with the infant: They only looked at each other or at the objects they acted on. Floor-to-ceiling white curtains surrounded the apparatus and experimenters and hid the testing room from the infants. Stimuli included mini-Oreo cookies, two white plates, five colorful stickers, five pieces of yellow paper, and an open black-and-white treasure box.

During each testing session, a metronome beat softly to help the experimenters adhere to the events’ second-by-second scripts. One camera captured an image of the events, and another camera captured an image of the infant. The two images were combined, projected onto a monitor located behind the apparatus, and watched by the supervisor to confirm that the events followed the prescribed scripts. The images were also recorded, and recorded sessions were checked off-line for experimenter and observer accuracy.

Trials

Infants in each group first received three familiarization trials. Each consisted of a 17-s computer-controlled initial phase followed by an infant-controlled final phase. During the initial phase, infants saw the scripted actions appropriate for their condition, ending with a paused scene; during the final phase, infants watched this paused scene until the trial ended. Infants in the inconsistent, control, and consistent groups also received a test trial that varied across groups and conditions, as explained in the text. The initial phase of the test trial lasted 44 s, except for the control no-knowledge subgroup where it lasted 49 s (a longer initial phase was needed to allow agent2 time to open her window after agent1’s departure). Finally, each test trial was preceded by a pretest trial that had only a 20-s computer-controlled initial phase and was identical to the beginning portion of the test trial: Agent1, or agent3 in the control new-agent subgroup, sat alone (agent2’s window was closed) and decorated and stored two papers (leaving three for the test trial), to give infants additional exposure to her sequence of actions and help them understand its goal.

Procedure

Each infant sat on a parent’s lap centered in front of the apparatus. To avoid influencing infants’ responses, parents were instructed to remain silent and neutral throughout the testing session, and to close their eyes for the test trial in Experiments 2 and 3 (infants in Experiment 1 received only familiarization trials). In the pretest and test trials of Experiments 2 and 3, two observers monitored the infant’s looking behavior through peepholes in large cloth-covered frames on either side of the apparatus; each observer pressed a button (linked to a computer) when the infant attended to the events, and looking times were computed using the primary observer’s responses. Inter-observer agreement during the final phase of the test trial was calculated by dividing the number of 100-ms intervals in which the two observers agreed by the total number of intervals in the final phase. Agreement was calculated for 116/120 infants and averaged 92% per infant. To ensure that the primary observer was blind to the infant’s condition, the primary observer was absent from the testing room during the familiarization trials. In Experiment 1, only the secondary observer was present; an offline observer coded each infant’s recorded testing session from silent video, with the portion of the computer screen showing the events hidden from view, to ensure that the observer was blind to the infant’s condition (the observer correctly guessed whether infants saw give or steal events for only 23/40 infants, two-tailed cumulative binomial probability p = 0.430). Looking times recorded by the secondary observer (give condition: M = 14.48, SD = 4.83; steal condition: M = 14.28, SD = 5.41) and the offline observer (give condition: M = 14.08, SD = 5.37; steal condition: M = 14.06, SD = 5.16) were highly similar, and inter-observer agreement averaged 86% per trial per infant. The secondary observer’s responses were therefore used to compute infants’ looking times in the familiarization trials for all three experiments.

Infants were highly attentive during the initial phase of each of the three familiarization trials; across the three experiments, they looked, on average, for 98% of each initial phase. Infants in Experiments 2 and 3 were also highly attentive during the initial phases of the pretest and test trials; on average, they looked for 98% of each phase. The final phase of each familiarization and test trial ended when infants (a) looked away for one (familiarization) or two (test) consecutive seconds after having looked for at least five cumulative seconds, or (b) looked for a maximum of 30 cumulative seconds. A longer look-away criterion was used in the test trial to give infants ample opportunity to reason about the outcome they had seen. When the computer signaled that a trial had ended, the supervisor lowered the curtain at the front of the apparatus and stimuli were readied for the next trial.

Statistics

Frequentist tests were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26, and BF tests were performed using JASP version 0.18.1. Levene’s tests confirmed the homogeneity of variances for the familiarization data (baseline, inconsistent, control, and consistent groups) and the test data (inconsistent, control, and consistent groups) of Experiments 1 − 3. Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests indicated that not all groups had normal distributions in the familiarization and test data. Normality violations are common in looking-time experiments with infants, due in part to the fact that trials have set minimal and maximal values, as noted in the previous section. Although ANOVAS are robust against normality violations77, for all key results we also performed non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, which make no normality assumption; results were identical to those of the ANOVAS.

Preliminary analyses

Infants’ sex, as reported by parents, was included as a factor in a preliminary analysis of the familiarization data in the give and steal conditions of the baseline, inconsistent, control, and consistent groups in Experiments 1−3. The ANOVA revealed no significant interaction of infants’ sex with either condition or group, both Fs ≤ 1.400, ps ≥ 0.245, \({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}{\rm{s}}\) ≤ 0.028, 90% CI for the largest \({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}\) = [0.000, 0.069]. Similarly, infants’ sex was included as a factor in a preliminary analysis of the test data in the give and steal conditions of the inconsistent, control, and consistent groups. The ANOVA again revealed no significant interaction of infants’ sex with either condition or group, both Fs ≤ 0.757, ps ≥ 0.386, \({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}{\rm{s}}\) ≤ 0.007, 90% CI for the largest \({{{{\rm{\eta }}}}_{{{\rm{p}}}}}^{2}\) = [0.000, 0.054]. In each case, the data were pooled across infants’ sex in subsequent analyses.

Online surveys with adults

When describing the actions we showed infants in Experiments 1 − 3, we made claims about the value of individual actions (e.g., moderately positive or negative in value) and about the acceptability of reciprocal actions (e.g., inconsistent or consistent with reciprocity). As manipulation checks for these descriptions, we tested adults in two online Qualtrics (Provo, UT) surveys, using written scenarios adapted from our events. In one survey (N = 115), adults rated the value of individual actions toward strangers. In the other survey (N = 130), adults rated the plausibility of reciprocal actions between strangers. Like infants’ responses, adults’ ratings were generally in line with our descriptions (e.g., helping a stranger who has stolen your cookie, or harming a stranger who has given you a cookie, were both rated as implausible scenarios), supporting our interpretations of infants’ responses (for methods and results, see Supplementary Note 1).

Reporting summary

Further information on the methods of Experiments 1−3 is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The infant data generated in Experiments 1 − 3 have been deposited on the Open Science Framework under the name “Jin et al. infant dataset”78 and are publicly available at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/FDQS2. The adult data generated in the online surveys reported in Supplementary Note 1 are available at the same link under the name “Jin et al. adult dataset”.

References

Baillargeon, R., et al. Psychological and sociomoral reasoning in infancy. in APA Handbook of Personality and Social Psychology, Volume 1: Attitudes and Social Cognition (eds. Borgida, E. & Bargh, J.) 79−150 (American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C., 2015).

Ting, F., Buyukozer Dawkins, M., Stavans, M. & Baillargeon, R. Principles and concepts in early moral cognition. in The Social Brain (ed. Decety, J.) 41−65 (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2020).

Brewer, M. B. The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love and outgroup hate? J. Soc. Issues 55, 429–444 (1999).

Dawes, C. T., Fowler, J. H., Johnson, T., McElreath, R. & Smirnov, O. Egalitarian motives in humans. Nature 466, 794–796 (2007).

Fehr, E. & Schurtenberger, I. Normative foundations of human cooperation. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 458–468 (2018).

Graham, J. et al. Moral foundations theory: the pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 47, 55–130 (2013).

Jackendoff, R. Language, Consciousness, Culture: Essays on Mental Structure (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 2007).

Rai, T. S. & Fiske, A. P. Moral psychology is relationship regulation: Moral motives for unity, hierarchy, equality, and proportionality. Psychol. Rev. 118, 57–75 (2011).

Shweder, R. A., Much, N. C,. Mahapatra, M. & Park, L. in Morality and Health (eds. Brandt, A. & Rozin, P.) 119−169 (Routledge, New York, 1997).

Tajfel, H., Billig, M. G., Bundy, R. P. & Flament, C. Social categorization and intergroup behaviour. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1, 149–178 (1971).

Tooby, J., Cosmides, L. & Price, M. E. Cognitive adaptations for n-person exchange: The evolutionary roots of organizational behavior. Manag. Decis. Econ. 27, 103–129 (2006).

Van Vugt, M., Hogan, R. & Kaiser, R. B. Leadership, followership, and evolution. Am. Psychol. 63, 182–196 (2008).

Buyukozer Dawkins, M., Sloane, S. & Baillargeon, R. Do infants in the first year of life expect equal resource allocations? Front. Psychol. 10, 116 (2019).

Meristo, M., Strid, K. & Surian, L. Preverbal infants’ ability to encode the outcome of distributive actions. Infancy 21, 353–372 (2016).

Schmidt, M. F. H. & Sommerville, J. A. Fairness expectations and altruistic sharing in 15-month-old human infants. PLoS One 6, e23223 (2011).

Sloane, S., Baillargeon, R. & Premack, D. Do infants have a sense of fairness? Psychol. Sci. 23, 196–204 (2012).

Wang, Y. & Henderson, A. M. Just rewards: 17-month-old infants expect agents to take resources according to the principles of distributive justice. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 172, 25–40 (2018).

Buon, M. et al. Friend or foe? early social evaluation of human interactions. PloS ONE 9, e88612 (2014).

Ting, F. & Baillargeon, R. Toddlers draw broad negative inferences from wrongdoers’ moral violations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2109045118 (2021).

Bian, L. & Baillargeon, R. When are similar individuals a group? early reasoning about similarity and in-group support. Psychol. Sci. 33, 752–764 (2022).

Bian, L., Sloane, S. & Baillargeon, R. Infants expect ingroup support to override fairness when resources are limited. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 2705–2710 (2018).

Jin, K. & Baillargeon, R. Infants possess an abstract expectation of ingroup support. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 8199–8204 (2017).

Jin, K., Houston, J. L., Baillargeon, R., Groh, A. M. & Roisman, G. I. Young infants expect an unfamiliar adult to comfort a crying baby: Evidence from a standard violation-of-expectation task and a novel infant-triggered-video task. Cogn. Psychol. 102, 1–20 (2018).

Powell, L. J. & Spelke, E. S. Preverbal infants expect members of social groups to act alike. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, E3965–E3972 (2013).

Pun, A., Birch, S. J. & Baron, A. S. The power of allies: infants’ expectations of social obligations during intergroup conflict. Cognition 211, 104630 (2021).

Rhodes, M., Hetherington, C., Brink, K. & Wellman, H. Infants’ use of social partnership to predict behavior. Dev. Sci. 18, 909–916 (2015).

Spokes, A. C. & Spelke, E. S. The cradle of social knowledge: Infants’ reasoning about caregiving and affiliation. Cognition 159, 102–116 (2017).

Ting, F., He, Z. & Baillargeon, R. Toddlers and infants expect individuals to refrain from helping an ingroup victim’s aggressor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 6025–6034 (2019).

Margoni, F., Baillargeon, R. & Surian, L. Infants distinguish between leaders and bullies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E8835–E8843 (2018).

Stavans, M. & Baillargeon, R. Infants expect leaders to right wrongs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 16292–16301 (2019).

Beltran, D. G., Ayers, J. D., Munoz, A., Cronk, L. & Aktipis, A. What is reciprocity? A review and expert-based classification of cooperative transfers. Evol. Hum. Behav. 44, 384–393 (2023).

Carter, G. The reciprocity controversy. Anim. Behav. Cogn. 1, 368–386 (2014).

Trivers, R. L. The evolution of reciprocal altruism. Q. Rev. Biol. 46, 35–57 (1971).

Gouldner, A. W. The norm of reciprocity: a preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 25, 161–178 (1960).

Axelrod, R. & Hamilton, W. D. The evolution of cooperation. Science 211, 1390–1396 (1981).

Delton, A. W., Krasnow, M. M., Cosmides, L. & Tooby, J. Evolution of direct reciprocity under uncertainty can explain human generosity in one-shot encounters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 13335–13340 (2011).

Fehr, E. & Gächter, S. Fairness and retaliation: the economics of reciprocity. J. Econ. Perspect. 14, 159–181 (2000).

Gurven, M. The evolution of contingent cooperation. Curr. Anthropol. 47, 185–192 (2006).

Jaeggi, A. V. & Gurven, M. Reciprocity explains food sharing in humans and other primates independent of kin selection and tolerated scrounging: a phylogenetic meta-analysis. Proc. Roy. Soc. B 280, 20131615 (2013).

Nowak, M. A. Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. Science 314, 1560–1563 (2006).

Margoni, F., Surian, L. & Baillargeon, R. The violation-of-expectation paradigm: A conceptual overview. Psych. Rev. 131, 716–748 (2024).

Hamlin, J. K. Context-dependent social evaluation in 4.5-month-old human infants: The role of domain-general versus domain-specific processes in the development of social evaluation. Front. Psychol. 5, 614 (2014).

Burkart, J. M. & Rueth, K. Preschool children fail primate prosocial game because of attentional task demands. PLoS ONE 8, e68440 (2013).

Dahlman, S., Ljungqvist, P. & Johannesso, M. Reciprocity in young children. Stockholm School of Economics, retrieved from http://ideas.repec.org/p/hhs/hastef/0674.html (2007).

House, B. R., Henrich, J., Sarnecka, B. & Silk, J. B. The development of contingent reciprocity in children. Evol. Hum. Behav. 34, 86–93 (2013).

House, B. R. Diverse ontogenies of reciprocal and prosocial behavior: Cooperative development in Fiji and the United States. Dev. Sci. 20, e12466 (2017).

Sebastian-Enesco, C., Hernandez-Lloreda, M. V. & Colmenares, F. Two and a half-year-old children are prosocial even when their partners are not. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 116, 186–198 (2013).

Dunfield, K. A., Kuhlmeier, V. A. & Murphy, L. Children’s use of communicative intent in the selection of cooperative partners. PLoS ONE 8, e61804 (2013).

Olson, K. R. & Spelke, E. S. Foundations of cooperation in young children. Cognition 108, 222–231 (2008).

Paulus, M. It’s payback time: preschoolers selectively request resources from someone they had benefitted. Dev. Psychol. 52, 1299–1306 (2016).

Rossano, F., Rakoczy, H. & Tomasello, M. Young children’s understanding of violations of property rights. Cognition 121, 219–227 (2011).

Vaish, A., Hepach, R. & Tomasello, M. The specificity of reciprocity: Young children reciprocate more generously to those who intentionally benefit them. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 167, 336–353 (2018).

Warneken, F. & Tomasello, M. The emergence of contingent reciprocity in young children. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 116, 338–350 (2013).

Dunfield, K. A. & Kuhlmeier, V. A. Intention-mediated selective helping in infancy. Psychol. Sci. 21, 523–527 (2010).

Fawcett, C. & Liszkowski, U. Infants anticipate others’ social preferences. Infant Child Dev. 21, 239–249 (2012).

Hamlin, J. K., Wynn, K. & Bloom, P. Social evaluation by preverbal infants. Nature 450, 557–559 (2007).

Lee, Y., Yun, J., Kim, E. & Song, H. The development of infants’ sensitivity to behavioral intentions when inferring others’ social preferences. PLoS One 10, e0135588 (2015).

Rhodes, M. Naïve theories of social groups. Child Dev. 83, 1900–1916 (2012).

Keysers, C., Gazzola, V. & Wagenmakers, E.-J. Using Bayes factor hypothesis testing in neuroscience to establish evidence of absence. Nat. Neurosci. 23, 788–799 (2020).

Schönbrodt, E. & Wagenmakers, E.-J. Bayes factor design analysis: planning for compelling evidence. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 25, 128–142 (2018).

Baillargeon, R., Scott, R. M. & Bian, L. Psychological reasoning in infancy. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 67, 159–186 (2016). (2016).

Choi, Y. & Luo, Y. 13-month-olds’ understanding of social interactions. Psychol. Sci. 26, 274–283 (2015).

Meristo, M. & Surian, L. Do infants detect indirect reciprocity? Cognition 129, 102–113 (2013).

Barclay, P. Biological markets and the effects of partner choice on cooperation and friendship. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 7, 33–38 (2016).

Bull, J. J. & Rice, W. R. Distinguishing mechanisms for the evolution of cooperation. J. Theor. Biol. 149, 63–74 (1991).

Kuhlmeier, V. A., Dunfield, K. A. & O’Neill, A. C. Selectivity in early prosocial behavior. Front. Psychol. 5, 836 (2014).

Noë, R. Cooperation experiments: coordination through communication versus acting apart together. Anim. Behav. 71, 1–18 (2006).

Schino, G. & Aureli, F. Reciprocity in group-living animals: Partner control versus partner choice. Biol. Rev. 82, 665–672 (2017).

Buresh, J. S. & Woodward, A. L. Infants track action goals within and across agents. Cognition 104, 287–314 (2007).

Egyed, K., Király, I. & Gergely, G. Communicating shared knowledge in infancy. Psychol. Sci. 24, 1348–1353 (2013).

Graham, S. A., Stock, H. & Henderson, A. M. E. Nineteen-month-olds’ understanding of the conventionality of object labels versus desires. Infancy 9, 341–350 (2006).

Chernyak, N., Leimgruber, K. L., Dunham, Y. C., Hu, J. & Blake, P. R. Paying back people who harmed us but not people who helped us: Direct negative reciprocity precedes direct positive reciprocity in early development. Psychol. Sci. 30, 1273–1286 (2019).

Fujisawa, K. K., Kutsukake, N. & Hasegawa, T. Reciprocity of prosocial behavior in Japanese preschool children. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 32, 89–97 (2008). (2008).

Kato-Shimizu, M., Onishi, K., Kanazawa, T. & Hinobayashi, T. Short-term direct reciprocity of prosocial behaviors in Japanese preschool children. PLoS ONE 17, e0264693 (2022).

Perlman, M., Lyons-Amos, M., Leckie, G., Steele, F. & Jenkins, J. Capturing the temporal sequence of interaction in young siblings. PLoS ONE 10, e0126353 (2015).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G. & Buchner, A. G. Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences (version 3.1). Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191 (2007).

Schmider, E., Ziegler, M., Danay, E., Beyer, L. & Bühner, M. Is it really robust? Reinvestigating the robustness of ANOVA against violations of the normal distribution assumption. Methodology 6, 147–151 (2010).

Jin, K., Ting, F., He, Z. & Baillargeon, R. Infants expect some degree of positive and negative reciprocity between strangers. Open Science Framework, https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/FDQS2 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grant RS-2023-00245011 from the National Research Foundation of Korea (to K.J.) and by grants 52034 and 60847 from the John Templeton Foundation (to R.B.). We thank Dov Cohen and Leda Cosmides for helpful discussions; Yi Lin, Hohyun Jung, and Oakyoon Cha for their help with the statistical analyses; the UIUC Infant Cognition Lab for their help with the data collection; graphic illustrator Steve Holland for his help with the figures; and the families who participated in the experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.J., F.T., Z.H., and R.B. designed the research; K.J., F.T., and Z.H. performed the research; K.J. analyzed the data; and K.J., F.T., Z.H., and R.B. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jin, Ks., Ting, F., He, Z. et al. Infants expect some degree of positive and negative reciprocity between strangers. Nat Commun 15, 7742 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51982-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51982-7

- Springer Nature Limited