Abstract

Introduction As an attempt to provide supporting evidence for the formulation of future educational strategies on knowledge translation, this systematic review assessed and synthesised the available evidence related to the dentists' awareness, perceived and actual knowledge of evidence-based dentistry (EBD) principles, methods and practices.

Methods Primary studies that considered dentists' reports collected from interviews, questionnaires, or conversation sessions were selected. Studies enrolling students, dental hygienists, or other health professionals were not included. Reviews, editorials, letters, study protocols, articles presenting knowledge translation strategies and initiatives, examples of EBD approaches to specific clinical questions, and guidelines focused on EBD implementation were also excluded. Cochrane, Embase, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science databases were searched. Grey literature was partially covered by the Google Scholar search and the reference lists of the pre-selected studies. The study search was concluded in February 2021. Descriptive data of the selected studies were synthesised, and the risk of bias was assessed according to the National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies.

Results Twenty-one articles were included. High percentages of dentists were aware of EBD. Variable proportions of professionals declared to have some understanding of EBD, although few presented actual knowledge of principles, methods and practices.

Discussion Methodologically, most studies presented limitations regarding sample representativity, participation rates, detailing of the outcome measures, and validation of the assessment tools. Additionally, extensive overall ranges of responses were often observed across the studies, possibly as a result of heterogeneity across samples and assessment tools. The authors thus suggest developing valid questionnaires including all dimensions (awareness, perceived knowledge and actual knowledge) within an assessment tool. This would contribute to establishing knowledge translation strategies to overcome specific gaps in EBD knowledge.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Evidence-based practice is defined as 'the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of the best current evidence in making decisions about the care of patients'.1 With the increasing number of patient care-related articles being published and accessed by dental professionals, clinicians are likely to achieve an increased level of confidence during clinical decision-making.2 Still, many dentists tend to rely solely on what they have learned during their training or personal experience.3,4 Moreover, obstacles to implementing evidence-based dentistry (EBD) have also been reported,5 including not only those that are self-related, but also evidence-, context- and patient-related barriers.

Recent studies have shown that a high percentage of dentists are aware of EBD principles, methods and practices.2,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 Dentists have also demonstrated enthusiasm, willingness and desire to implement EBD into daily clinical practice.2,12 However, although dentists have expressed positive attitudes towards EBD, they apparently lack knowledge about EBD.9,12 In the health research literature, an overlap of meanings between awareness and knowledge is often seen.13 Hence, a clear definition appears to be necessary, since it is the translation of knowledge into practice that might positively impact health care.14

To accurately incorporate evidence-based concepts into clinical practice, a clear understanding is required, including an awareness of the basic terminology and principles.15 Therefore, a systematic review (SR) of this topic should help establish knowledge translation strategies to overcome specific and pre-identified gaps in dentists' understanding of the main concepts involved in EBD. The purpose of this SR was to assess and synthesise the available evidence related to the dentists' awareness of, and perceived and actual knowledge of, EBD principles, methods and practices.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This manuscript presents information about dentists' awareness of EBD and their perceived and actual knowledge of EBD principles, methods and practices. The SR protocol has been registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42017056298).

We considered 'awareness' to be a state of consciousness about the existence of any given information. To confirm or refute awareness of a term or a subject, the respondents should have answered questions such as 'Are you aware of…?' or 'Have you ever heard/read about…?' Awareness of a term/subject could also be confirmed/refuted whenever the response alternatives included terms such as 'aware'/'unaware' or '(not) heard/read about'.

'Awareness' must be differentiated from 'knowledge', which might instead be acquired from experience and/or previous learning. We thus considered 'knowledge' to be a more advanced state of realisation than 'awareness', in which dentists claim to (that is, possess perceived knowledge) or understand (that is, possess actual knowledge as certified by experts) a specific term/subject.

We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement checklist to report this review.16

Information sources and search

We performed a search up to February 2021 of the following sources: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Embase, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science. Grey literature was partially covered by the Google Scholar search (first 100 hits) and the reference lists of the pre-selected studies. There were no restrictions concerning the year or language. Initially, we developed a search strategy for the PubMed database (online Supplementary Appendix 1), which was later adapted to the other search sources.

Eligibility criteria

We included primary quantitative and qualitative studies in which the investigators presented information collected from interviews, questionnaires, or conversation sessions with dentists. Exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Studies enrolling dentists along with other professionals, but in which the investigators failed to report the results separately for the various professions

-

Studies in which the investigators exclusively enrolled dentistry students, dental hygienists, or other health care professionals

-

Studies that did not concern awareness of EBD and perceived and actual knowledge of EBD

-

Articles presenting knowledge translation strategies and initiatives (study protocols), examples of EBD approaches to specific clinical questions (case scenarios), and practical guidelines focused on EBD implementation

-

Narrative reviews or SRs, meta-analyses (MAs), editorials, letters, study protocols

-

Duplicate results/samples.

Study selection

Two researchers (MFNF, MGR) independently reviewed titles and abstracts, pre-selecting studies that apparently presented information on awareness of EBD and perceived and actual knowledge of EBD principles, methods and practices. In case of disagreement, we retrieved the full-text documents and discussed them until reaching a consensus.

Data items and collection

Two researchers (MFNF, MLA) independently extracted the included studies' characteristics and results and recorded them with standardised tables. Then, another researcher (CFM) reviewed the extracted information. Disagreements were resolved by re-examining the original documents. Whenever necessary, we contacted the authors of the selected studies to inquire about missing or incomplete data.

Summary measures and synthesis of the results

The study outcomes were dentists' awareness of EBD and their perceived and actual knowledge of EBD principles, methods and practices. Descriptive data were collected from the results of the included studies and synthesised descriptively, since we did not consider them adequate to be merged in an MA because of the large degree of methodological and clinical (sample origin) heterogeneity.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Two examiners (RPACS, LAAJ) used the National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies17 to assess the quantitative studies, because all of them were observational. A third reviewer (CFM) was involved in case of disagreement.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

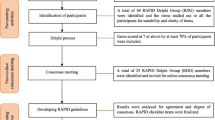

The selection process resulted in a final list of 21 included studies, which covered either 'awareness',2,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,15,18,19,20,21,22,23 'perceived knowledge'2,6,7,8,9,12,15,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 and/or 'actual knowledge'2,10,12,20,21,22,25,29 (Fig. 1). All of the included studies were cross-sectional quantitative studies, and their detailed characteristics are provided in online Supplementary Table 1. Online Supplementary Appendix 2 indicates the specific reasons for exclusions after full-text readings.

Summary of the results

The results of the included studies were organised into three domains (awareness, perceived knowledge and actual knowledge), and they are presented in the following sections.

Awareness of EBD principles, methods and practices

In several studies,2,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 most respondents declared that they were aware of EBD-related terms, with frequencies ranging from 69.9%12 to 93.0%.2 Only one study presented a relatively lower frequency (38.0%),23 which the authors attributed to a potential gap in the local EBD education.23

A minority of the interviewees were unaware of the PubMed/Medline database (28.9%9 and 11.8%).7 Additionally, according to the results of another study,21 PubMed was reported as highly acknowledged by the respondents (4.4/5.0). In contrast, several studies,2,7,9,12,15,18,23 found low percentages of participant awareness. In contrast, several studies,2,7,9,12,15,18,23 found low percentages of participant awareness the Cochrane Database/Collaboration (27.0%2 to 61.3%7).

The included studies also asked participants questions about their awareness of specific scientific journals. According to these investigations, 70.3%18 and 72.4%7 of the dentists indicated that they were aware of the Journal of Evidence-Based Dental Practice. In other studies, 31.8%,9 78.6%7 and 84.4%18 of the respondents confirmed their awareness of the journal Evidence-Based Dentistry. A high frequency of non-specialist respondents9 and the recruitment of graduate students sited in university environments18 might explain this wide data range in the results of different studies. Additionally, higher awareness rates were observed in more recent studies,7,18 as opposed to the former.9 This might explain the variability observed for the response ranges and the potential increase in EBD focus in our practice over time. Respondents indicated relatively lower rates of awareness of other sources of critical summaries, such as the American Dental Association (ADA) Critical Summaries and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (56.2%18 and 36.6%,23 respectively).

Two investigations assessed respondents' awareness of the Turning Research Into Practice (TRIP) database.7,18 While 35.4%7 of graduate students indicated that they were aware of this source, only 14.0%18 of dental practitioners reported awareness. As for other EBD sources, one study reported that 90.0%20 of the interviewed dentists claimed to be aware of Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs), but only 68.0% claimed to 'know about' them.19 In contrast, several other studies reported lower rates of unawareness concerning SRs (7.0%2 and 4.4%12). The rates of reported awareness regarding other EBD sources were also collected and are shown in Table 1.

Perceived knowledge of EBD principles, methods and practices

According to four studies, high proportions of dentists reported having at least some understanding of EBD2,9,12,26 (80.8%26 to 97.8%12). The relatively lower frequencies observed in two other studies (44.7%8 and 47.3%25) could be related to the respondents' shorter-term professional experience.

Except for one study, which documented a relatively lower rate of perceived knowledge about SRs (42.4%),23 several others2,7,8,9,12,15 found that a high proportion of dental professionals claimed to know about SRs (70.5%8 to 95.5%12). This discrepancy might be because most of the respondents from the former study23 did not have an internet connection in their workplaces. This could have reduced their opportunities to access information and obtain knowledge about SRs or other related subjects. Two studies found that most respondents reported a certain level of knowledge about randomised clinical trials (RCTs) (70.9%9 and 98.0%15). In contrast, other studies7,9,15,20,23 found that respondents presented relatively lower rates of perceived knowledge of MAs (31.7%9 to 68.0%15).

The selected studies presented high frequencies of perceived knowledge about RCT-related topics, such as 'clinical effectiveness' (82.0%2 and 97.7%12), 'randomisation' (96.2%7) and 'blinding' (80.0%15 and 86.9%7). Other studies found that moderate numbers of respondents reported understanding on topics related to observational studies, such as 'absolute risk' (64.0%7 and 46.2%23), 'relative risk' (64.2%,20 88.0%7 and 43.7%23) and 'odds ratio' (61.0%,15 48.4%20 and 29.6%23). As for terms related to diagnostic studies, such as 'sensitivity'7,20 and 'specificity',7,15 the respondents reported possessing perceived knowledge at relatively higher rates (63.4%20 to 89.0%7).

In the selected studies, most respondents reported some understanding of 'confidence interval' (70.0%,15 56.7%,20 68.5%7). The proportion of interviewees that reported some understanding of 'heterogeneity' varied from 35.4%23 to 76.0%;7 but in the former study,23 an additional response alternative was available, in which the respondents were able to acknowledge their lack of knowledge, in addition to reporting their willingness to obtain knowledge. This added alternative ('do not understand, but would like to') was strongly preferred among respondents.23 Of the general dental practitioners surveyed, 58.6%9 claimed to know about 'strength of evidence', while a relatively higher percentage of orthodontics specialists (92.0%) claimed to have this knowledge.15

In several studies,2,12,22,24,27 most respondents (60.5%24 to 93.0%2) claimed to know about 'critical appraisal of the literature'. The only study that reported a relatively lower rate (23.1%) also observed an overall low rate of knowledge perception among the respondents concerning other subjects, illustrating that the respondents had an insufficient basic understanding and knowledge of the definitions and procedures in statistics and epidemiology.25 Frequencies related to the knowledge perception of other topics are shown in online Supplementary Table 2.

Actual knowledge of EBD principles, methods and practices

In one study,12 a high percentage of respondents correctly identified the definition of EBD (94.2%), the steps involved in EBD (95,6%), the benefits of EBD for patients (97.8%) and the advantages for those who practise EBD (97.8%). However, when asked to describe the EBD concept with their own words, another study2 found that only a few respondents (29,4%) could correctly define EBD.

When asked about the factors that should be considered during the clinical decision-making process, most professionals agreed with statements that included diagnosis and the selection of optimal treatments for individual patients (75.2% and 88.9%) and the practitioners' experience (71.5% and 88.0%).20 However, in another study, when asked if evidence from all published articles can be used in EBD, nearly half of the sample (43.7%) answered positively,12 which was also the case (46.8%) when respondents were asked if EBD is based on expert opinion20 and if the best and quickest way to find the evidence was by reading textbooks or asking experienced colleagues (42.2%).12

Tests were also developed in four studies to measure the professionals' overall knowledge of EBD. The percentages of correct answers were variable (19.0%,29 43.0%,20 55.0%22 and 71.8%25). In another study,21 when specific skills were evaluated, poor performances were observed for formulating PICO questions (0.1/3.0), searching PubMed (0.2/8.0) and finding evidence (1.2/6.0). When asked to identify the most important factors in an RCT, respondents most often indicated sample size (75.0%), randomisation (49.0%) and blinding (47.0%).2 Further details about the dentists' actual knowledge are provided in Table 2.

Risk of bias within studies

Most of the included studies presented issues regarding participation rates,6,7,11,15,19,20,26,27 or in detailing of the outcome measures.6,7,8,10,11,12,15,18,19,20,21,26 A full appraisal of the studies is provided in Table 3.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

According to several studies,2,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 most professionals seemed to be aware of EBD. Despite these results, one may easily argue that EBD awareness might not necessarily reflect actual knowledge, as the difference in meaning between the terms 'awareness' and 'knowledge' is somewhat blurred.13 According to McCallum et al.,30 although awareness and knowledge are not qualitatively different, they occupy opposite positions on a knowledge continuum spectrum. Given this, variable percentages of dentists claimed to have some knowledge about EBD.2,6,8,9,12,21,25,26 While many dentists could identify the correct definition of EBD,12 only a few could correctly define it themselves.2 Even though professionals were frequently able to accurately recognise the steps involved in EBD, the potential benefits and advantages of EBD in clinical practice,12,20 significant proportions of dentists still showed fundamental misconceptions regarding the components that, according to their perception, should comprise EBD; for example, the opinions of experienced peers,20 textbooks, or any published article.12 Hence, it can be inferred that, even though many dentists are aware of EBD, we cannot assume that they understand the meaning of EBD, considering the information we were able to retrieve.

Although the PubMed/Medline database appears to be frequently used by,7,9 and is well-known21 to, most dentists, the Cochrane database is less so.2,7,9,12,15,18,23 We deduce that this might be attributed to the latter's restricted access. Even though we have observed overall poor performances for formulating proper PICO questions, searching, and finding evidence,21 the PubMed/Medline database might still be considered an important resource for clinicians and researchers due to its accessibility.31

The application of the knowledge derived from full articles accessed via PubMed, or any other database, requires several abilities on the part of their readers. Besides formulating answerable PICO questions, searching, and finding studies, another essential skill is critically evaluating the selected literature. Even though the critical thinking ability seems to have a close relationship with working competence,32,33 the results collected here in this regard revealed variable rates of perceived knowledge,2,12,22,24,25,27 which indicates another possible gap to be addressed by dental professionals.

Concerning knowledge of particular study designs, most dentists reported some understanding of RCTs in general9,15 or more specifically.2,7,12,15 As for the SR study design, the studies revealed high rates of awareness2,12 and perception of knowledge.2,7,8,9,12,15 Even though we identified an overall perception of adequate knowledge concerning RCTs, SRs and related terms among respondents, none of the included studies could certify actual knowledge. Furthermore, only moderate percentages of respondents claimed to have perceived knowledge of observational or diagnostic studies.7,15,20,23 While most of the interviewed professionals declared to have perceived knowledge of 'confidence interval'7,15,20 and 'heterogeneity',9,15 variable percentages of respondents claimed to have perceived knowledge of the term 'strength of evidence'.7,23 This may indicate that professionals might be more familiar with study designs that investigate therapeutic interventions (RCT and SR). Nevertheless, a dentist's ability to critically assess clinical evidence should ideally include understanding other methodological concepts and general statistical notions.

In addition to limited EBD training/skills, practical issues, such as shortage of time, have been indicated as a significant barrier to EBD practice.5 To overcome this obstacle, critical summaries and evidence-based treatment recommendations - or CPGs - have emerged as highly condensed, easily accessible vehicles for staying current with research findings.34,35 Recommendations have already been made for authors to produce summarised versions of their research,36,37 and although most of the interviewees seem to be aware of specific journals that are often dedicated to disseminating critical summaries,7,18 other databases, such as ADA Critical Summaries and DARE, seem to be less familiar to them.18,23 Although the number of critical summaries available may be limited in these electronic sources, they are fully accessible to unsubscribed users, and they provide content that was previously synthesised considering the risk of bias.

The frequency of awareness of TRIP, a database that includes a wide range of CPGs, was also low,7,18 even though more significant numbers of practitioners reported being aware of this type of document.19,20 CPGs are systematically developed recommendations to assist the practitioner and the patient with appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances.38 Unfortunately, dental CPGs are still insufficient, and many are still of low quality, are unclear, or do not consult reliable information sources.39,40,41 Therefore, practitioners should become familiar with the use of objective parameters when critically consulting CPGs.42

Limitations

In terms of dentists' actual knowledge, the selected studies' data is quite limited, controversial and arguable. The application of general tests of knowledge disclosed variable percentages of correct answers.20,25,29 This discrepancy might be related to the different assessment tools used to elicit the responses. The only study that found a high level of actual knowledge about EBD was the one that used multiple-choice options to collect the respondents' answers.25 Therefore, these results seem to be inherently biased. Furthermore, even if some of the studies included here apparently confirmed actual knowledge of EBD,2,12,20,25 this does not necessarily mean that dentists are implementing EBD principles during their professionals' routine practice.

Methodologically, the quantitative results summarised here must be considered cautiously. Most studies presented limitations regarding sample representativity,6,7,8,10,11,15,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,27,29,30 participation rates,6,7,11,15,19,20,26,27 detailing of the outcome measures6,7,8,10,11,12,15,18,19,20,21,26 and validation of the assessment tools. 2,6,7,8,9,11,15,18,19,20,21,22,24,26,30 Additionally, extensive overall ranges of responses were often observed for similar questions across the studies. This might be related to the significant heterogeneity identified across samples, as the assessment tools or investigation methods were rarely uniform, and the wide time range throughout which the included studies were conducted (from 20022 to 202022,27). Due to the clear heterogeneity among studies, the conduction of any MA was not justified.

Hence, the quantitative results of the selected studies should not be extrapolated globally. Since there seems to be scarce information derived from properly validated assessment tools, educators or policymakers might still be provided with reliable information before designing potentially effective educational strategies. Therefore, future research in the EBD field should develop questionnaires that combine all dimensions (awareness of EBD, perceived knowledge of EBD and actual knowledge of EBD) within a single assessment tool. In addition, a validation process would also be warranted, with EBD actual practice as a reference. This would thus help establish future knowledge translation strategies to overcome specific and pre-identified gaps in dentists' knowledge of the main principles, methods and practices involved in EBD.

This SR was not aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of educational interventions related to EBD on dental practitioners, and the results collected here are not sufficient to support their recommendation. Therefore, we believe that future syntheses should be performed with this specific purpose. Nevertheless, we assume that continuing education initiatives covering EBD principles and the development of critical appraisal skills for multiple study designs and documents, such as CPGs, would be somewhat beneficial for clinicians interested in improving their practice. Although there have been important incentives for dental practitioners to adopt EBD habits, it seems clear that improving our understanding on the fundamentals and skills is an essential pre-condition.

Based on low certainty of the evidence, dentists seem to be aware of EBD in general, the PubMed/Medline database, EBD scientific journals and CPGs. Concerning perceived knowledge, variable proportions of dentists claimed to know about EBD, and most reported a certain level of understanding of SRs and RCTs. However, actual knowledge has scarcely been assessed, and few dentists seem to really understand EBD principles, methods and practices.

References

Sackett D L, Rosenberg W M, Grey J A, Haynes R B, Richardson W S. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ 1996; 312: 71-72.

Iqbal A, Glenny A M. General dental practitioners' knowledge of and attitudes towards evidence based practice. Br Dent J 2002; 193: 587-591.

Linnebur S A, Ellis S L, Astroth J D. Educational practices regarding anticoagulation and dental procedures in U S. dental schools. J Dent Educ 2007; 71: 296-303.

McGlone P, Watt R, Sheiham A. Evidence-based dentistry: an overview of the challenges in changing professional practice. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 636-639.

Neuppmann Feres M F, Roscoe M G, Job S A, Mamani J B, Canto G D L, Flores-Mir C. Barriers involved in the application of evidence-based dentistry principles: A systematic review. J Am Dent Assoc 2020; DOI: 10.1016/j.adaj.2019.08.011.

Ahad M, Sukumaran G. Awareness, attitude and knowledge about evidence based dentistry among the dental practitioner in Chennai city. Res J Pharm Technol 2016; 9: 1863-1866.

Al-Ansari A, ElTantawi M. Factors affecting self-reported implementation of evidence-based practice among a group of dentists. J Evid Based Dent Pract 2014; 14: 2-8.

Gupta M, Bhambal A, Saxena S, Sharva V, Bansal V, Thakur B. Awareness, Attitude and Barriers Towards Evidence Based Dental Practice Among Practicing Dentists of Bhopal City. J Clin Diagn Res 2015; DOI: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/12814.6342.

Rabe P, Holmen A, Sjogren P. Attitudes, awareness and perceptions on evidence based dentistry and scientific publications among dental professionals in the county of Halland, Sweden: a questionnaire survey. Swed Dent J 2007; 31: 113-120.

ALmalki W D, Ingle N, Assery M, Alsanea J. Dentists' Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Regarding Evidence-Based Dentistry Practice in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2019; DOI: 10.4103/jpbs.JPBS_247_18.

Yamalik N, Nemli S K, Carrilho E et al. Implementation of evidence-based dentistry into practice: analysis of awareness, perceptions and attitudes of dentists in the World Dental Federation-European Regional Organisation zone. Int Dent J 2015; 65: 127-145.

Yusof Z Y, Han L J, San P P, Ramli A S. Evidence-based practice among a group of Malaysian dental practitioners. J Dent Educ 2008; 72: 1333-1342.

Trevethan R. Deconstructing and Assessing Knowledge and Awareness in Public Health Research. Front Public Health 2017; 5: 194.

Haynes B, Haynes G A. ACP Journal Club. What does it take to put an ugly fact through the heart of a beautiful hypothesis? Evid Based Med 2009; 14: 68-69.

Madhavji A, Araujo E A, Kim K B, Buschang P H. Attitudes, awareness, and barriers toward evidence-based practice in orthodontics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2011; DOI: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2010.05.023.

Page M, McKenzie J, Bossuyt P et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med 2021; DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003583.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies. 2021. Available at https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed August 2021).

Afrashtehfar K I, Eimar H, Yassine R, Abi-Nader S, Tamimi F. Evidence-based dentistry for planning restorative treatments: barriers and potential solutions. Eur J Dent Educ 2017; DOI: 10.1111/eje.12208.

Guncu G N, Nemli S K, Carrilho E et al. Clinical Guidelines and Implementation into Daily Dental Practice. Acta Med Port 2018; 31: 12-21.

Haron I M, Sabti M Y, Omar R. Awareness, knowledge and practice of evidence-based dentistry among dentists in Kuwait. Eur J Dent Educ 2012; DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2010.00673.x.

Qureshi A, Bokhari S A, Pirvani M, Dawani N. Understanding and practice of evidence based search strategy among postgraduate dental students: a preliminary study. J Evid Based Dent Pract 2015; 15: 44-49.

Vahabi S, Namdari M, Vatankhah M, Khosravi K. Evidence-Based Dentistry Among Iranian General Dentists and Specialists: A Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Study. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2020; 22: 1-7.

Rawat P, Goswami R P, Kaur G, Vyas T, Sharma N, Singh A. Knowledge, Attitude, and Behaviour toward Evidence-based Dentistry among Dental Professionals in Jodhpur Rajasthan, India. J Contemp Dent Pract 2018; 19: 1140-1146.

Ciancio M J, Lee M M, Krumdick N D, Lencioni C, Kanjirath P P. Self-Perceived Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes, and Use of Evidence-Based Dentistry Among Practitioners Transitioning to Dental Educators. J Dent Educ 2017; 81: 271-277.

Sabounchi S S, Nouri M, Erfani N, Houshmand B, Khoshnevisan M H. Knowledge and attitude of dental faculty members towards evidence-based dentistry in Iran. Eur J Dent Educ 2013; 17: 127-137.

Straub-Morarend C L, Marshall T A, Holmes D C, Finkelstein M W. Toward defining dentists' evidence-based practice: influence of decade of dental school graduation and scope of practice on implementation and perceived obstacles. J Dent Educ 2013; 77: 137-145.

Wudrich K M, Matthews D C, Brillant M S, Hamdan N M. Knowledge Translation Among General Dental Practitioners in the Field of Periodontics. J Can Dent Assoc 2020; 86: k5.

Pau A, Omar H, Khan S, Jassim A, Seow L L, Toh C G. Factors associated with faculty participation in research activities in dental schools. Singapore Dent J 2017; 38: 45-54.

Hinton R J, McCann A L, Schneiderman E D, Dechow P C. The winds of change revisited: progress towards building a culture of evidence-based dentistry. J Dent Educ 2015; 79: 499-509.

McCallum J M, Arekere D M, Green B L, Katz R V, Rivers B M. Awareness and knowledge of the U S. Public Health Service syphilis study at Tuskegee: implications for biomedical research. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2006; 17: 716-733.

Falagas M E, Pitsouni E I, Malietzis G A, Pappas G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J 2008; 22: 338-342.

Chang M J, Chang Y J, Kuo S H, Yang Y H, Chou F H. Relationships between critical thinking ability and nursing competence in clinical nurses. J Clin Nurs 2011; 20: 3224-3232.

Ross D, Schipper S, Westbury C et al. Examining Critical Thinking Skills in Family Medicine Residents. Fam Med 2016; 48: 121-126.

Chambers D, Wilson P M, Thompson C A, Hanbury A, Farley K, Light K. Maximizing the impact of systematic reviews in health care decision making: a systematic scoping review of knowledge-translation resources. Milbank Q 2011; 89: 131-156.

Song M, Spallek H, Polk D, Schleyer T, Wali T. How information systems should support the information needs of general dentists in clinical settings: suggestions from a qualitative study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2010; 10: 7.

Chalmers I, Haynes B. Reporting, updating, and correcting systematic reviews of the effects of health care. BMJ 1994; 309: 862-865.

Tricco A C, Cardoso R, Thomas S M et al. Barriers and facilitators to uptake of systematic reviews by policy makers and health care managers: a scoping review. Implement Sci 2016; 11: 4.

Woolf S H, Grol R, Hutchinson A, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: potential benefits, limitations, and harms of clinical guidelines. BMJ 1999; 318: 527-530.

Faggion Jr C M. Clinician assessment of guidelines that support common dental procedures. J Evid Based Dent Pract 2008; 8: 1-7.

Glenny A M, Worthington H V, Clarkson J E, Esposito M. The appraisal of clinical guidelines in dentistry. Eur J Oral Implantol 2009; 2: 135-143.

Shah P, Moles D R, Parekh S, Ashley P, Siddik D. Evaluation of paediatric dentistry guidelines using the AGREE instrument. Paediatr Dent 2011; 33: 120-129.

Brouwers M C, Kerkvliet K, Spithoff K, Consortium A N S. The A G R EE Reporting Checklist: a tool to improve reporting of clinical practice guidelines. BMJ 2016; DOI: 10.1136/bmj.i1152.

Acknowledgements

The authors have nothing to acknowledge. The authors are willing to provide template data collection forms, data extracted from included studies, data used for all analyses, analytic code, or any other materials used in the review, if requested.

Funding

The authors declare no funding sources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Murilo Fernando Neuppmann Feres: conception of the work, acquisition of data, data analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the work, critical review for intellectual content, final approval of the submitted version. Maxwell Lopes Albuini: acquisition of data, drafting the work, final approval of the submitted version. Renata Pires de Araújo Castro Santos: acquisition of data, drafting the work, final approval of the submitted version. Luciano Aparecido de Almeida-Junior: acquisition of data, data analysis, drafting the work, final approval of the submitted version. Carlos Flores-Mir: conception of the work, acquisition of data, data analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the work, critical review for intellectual content, final approval of the submitted version. Marina Guimarães Roscoe: conception of the work, acquisition of data, data analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the work, critical review for intellectual content, final approval of the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors deny any conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Feres, M., Albuini, M., de Araújo Castro Santos, R. et al. Dentists' awareness and knowledge of evidence- based dentistry principles, methods and practices: a systematic review. Evid Based Dent (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41432-022-0821-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41432-022-0821-2

- Springer Nature Limited