Abstract

Background/objectives

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is fast increasing in recent decades. Limited prospective studies are available on Mediterranean diet protective effect against T2D development. We assessed longitudinal association of the Mediterranean diet with T2D risk in Iranian men and women.

Subjects/methods

Diet was measured using a 168-item food frequency questionnaire in 2139 adults (free of T2D), aged 20−70 years. All individuals, based on the traditional Mediterranean diet score (MDS), received scores between 0 and 8 points. Multivariate hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were reported for the association of T2D and the MDS, with adjustment of diabetes risk score (DRS) and dietary energy intakes.

Results

During follow-up, a total of 143 events occurred. Individuals who had higher intakes of fish/sea foods, legumes, nuts, and monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) to saturated fatty acids (SFAs) ratio had a decreased risk of T2D. After adjustment for confounders, an inverse association was found between adherence to the MDS and T2D (HR = 0.48; 95% CI 0.27−0.83).

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrated an inverse association between the Mediterranean diet score and incidence of T2D.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D), as a public health problem, shows a significant increase in recent decades, and is a main cause of mortality worldwide [1]. On the other hand, by 2035, 592 million people will have T2D [2]. Studies indicated that prevalence of T2D for Iranian population was 7.2−17.2% in 2014 [3]. Based on the results of previous studies, both dietary habits and physical activity level are related mainly to preventing and managing diabetes [4, 5].

High-quality diets, which emphasizes on low dietary intake of red meat and high intake of vegetables and fruit, are related with a reduced risk of diabetes and cardiovascular risk factor [6, 7]. The Mediterranean diet pattern provides a balanced intake of fish, high amounts of legumes, fruit, whole grains, vegetables, and olive oil, and also low amounts of meat products [8,9,10]. This dietary pattern has previously been shown to have a preventing effect on diabetes risk [11,12,13]. Some studies however failed to report a significant relation between MDS and risk of T2D or insulin sensitivity [14, 15].

Limited studies are available on the association between Mediterranean diet and T2D among Middle Eastern populations. Therefore, we prospectively evaluated the relationship between adherence to the MDS, and the risk of T2D in 2139 Iranian adults.

Methods

Study design and subjects

The TLGS (Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study) is a cohort study of 15,005 persons, aged ≥3 years, in a representative sample of district 13 of Tehran, the capital city of Iran, for whom the baseline examination survey was conducted every 3 years. The beginning of the TLGS was from 1999 to 2001, and to recognize new cases of diseases, examinations have been performed every 3 years [16].

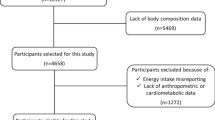

In the third phase (2006−2008) of the TLGS, from 12,523 subjects, aged ≥20 years, 4920 subjects were selected using the multistage cluster random sampling method. After excluding subjects who did not complete dietary assessments (n = 1458), their ages were <20 or ≥70 years at baseline (n = 504), had diabetes at the beginning of the study (n = 321), had unusual dietary energy intake (n = 284), or no information on biochemical, anthropometrics, and physical activity measurements (n = 63), and 2256 subjects were followed up for a median of 5.8 years. We also excluded subjects who had no follow-up (n = 117). Finally, a total of 2139 participants (1168 women and 971 men) entered in the analysis.

This study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. Informed consent was obtained from participants.

Demographic and anthropometric measurements

Information on demographics of individuals was obtained by a pretested questionnaire administered by trained interviewers [16].

Baseline anthropometric measurements were ascertained in all subjects. For weight measurement of participants, 100 g of sensitivity was used as a digital scale. The height of each participant was measured without shoes, and 0.5-cm sensitivity, using a tape meter. Waist circumference of the subjects was measured using a soft tape meter with minimum clothing, and 0.1-cm sensitivity, at the umbilicus. The BMI of each subject was computed by the formula: weight (kg) divided by height square (m2).

To evaluate the physical activity levels of participants, a reliable and valid Modifiable Activity Questionnaire (MAQ) was used [17]. Physical activity was expressed as metabolic equivalent hours per week (METs min/wk), and participants who had physical activity under 600 were considered as having low physical activity.

After a 15-min rest while the participants were in a seated position, blood pressure with an accuracy of 2 mm Hg was measured two times using Korotkoff sound technique and a standardized mercury sphygmomanometer by a trained nurse. We report the mean of the two measurements as the individual’s blood pressure.

Laboratory measurements

After 12−14 h of overnight fasting, blood samples were taken at the beginning of the study from all individuals. All analyses were performed using Pars Azmoon kits (Tehran, Iran). Serum glucose was measured using enzymatic colorimetric analysis method by glucose oxidase. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) was measured after apo-lipoprotein β precipitated with phosphotungstic acid. The standard 2-h plasma glucose test was performed for all participants who were not on antidiabetic drugs. Enzymatic colorimetric analysis with glycerol phosphate oxidase was used for triglyceride (TG) measurement.

Dietary assessment and Mediterranean diet score

In the TLGS, frequency for all foods and beverage intakes was obtained at baseline via a semiquantitative FFQ [18, 19]. To evaluate the reliability of nutrient and energy intakes in the FFQ, a semiquantitative FFQ (FFQ1 and FFQ2) was collected with a 14-month interval. The validity of FFQ was evaluated using a 24-h dietary recall that was gathered with a 12-month interval. Acceptable validity and reliability were reported for FFQ [19]. Because of incomplete Iranian food composition table (FCT), calculation of dietary intake of energy, micro-, and macronutrients was performed using the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) FCT.

Adherence to Mediterranean diet was assessed using Trichopoulou et al.’s Mediterranean diet score [20], which includes nine nutritional items; for religious reasons, alcohol was excluded from the final score. Therefore, in the present study, we constructed an 8-point score, including processed and red meat, vegetables, nuts, fruits, whole grains, legumes, fish (serving/d), and the MUFAs to SFAs ratio. The median consumption of each item was considered as the cutoff; scores of 0 and 1 were reported for under and above the median values of each of the items, which were beneficial to health, including MUFAs to SFAs ratio, whole grains, fruit, legumes, nuts, fish, and vegetables. Scores for all eight items were hence summed up to calculate MDS (range from 0 to 8).

Definition of outcomes and terms

T2D is a condition defined as occurring when at least one of the following criteria exist: consumption of any antidiabetic drugs, 2-h plasma glucose (2-h PG) ≥ 200 mg/dL, or fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥ 126 mg/dL [21]. We estimated the diabetes risk score (DRS) as follows: 5 points for having a family history of diabetes; FPG concentrations divided into <5, 5−5.5, and 5.6−6.9 mmol/L with 0, 12, and 33 points, respectively; systolic blood pressure (SBP) divided into three categories: <120, 120−140, and ≥140 mm Hg with 0, 3, and 7 points, respectively; waist to height ratio (WHtR) divided into three categories: <0.54, 0.54−0.59, and ≥0.59 with 0, 6, and 11 points, respectively; TG/HDL-C (≥3.5) (3 points), and TG/HDL-C (<3.5) (0 point) [22].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were done using SPSS version 19, with P values < 0.05 being considered statistically significant.

Baseline characteristics of the participants were compared by using chi-square tests for categorical variables, or independent t test for continuous variables. Categorization of subjects was performed according to tertiles of MDS. Mean ± SD of MDS in tertiles was 1.56 ± 0.62, 3.49 ± 0.50, and 5.42 ± 0.62, respectively. Cox proportional hazards regression model, with person-years as the underlying time metric, MDS as an independent variable, and incidence of T2D as a dependent variable was used to estimate HRs and 95% CIs. In the univariate analysis, variables with PE (P for entry) < 0.2 were determined as potential confounding variables for the multivariable models. We also evaluated the proportional hazard assumption, using Schoenfeld’s global test of residuals.

Results

Among 2139 adults (54.6% women) who completed the study, the average MDS was 3.4 on a 0−8-point scale for these individuals, and the incidence of T2D was 143 persons (6.6%).

The results showed that subjects in the highest tertiles of MDS at baseline had higher age, BMI and SBP, and a lower family history of T2D, and also were less smokers (P < 0.05). No significant difference was reported for FBG, diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and hypertension between individuals in the highest and lowest tertiles of MDS (Table 1). Participants in the lowest tertiles of MDS had less dietary intakes of total energy, MUFAs, polyunsaturated fats, and protein (P < 0.05). In contrast, those in the highest adherence had less consumptions of total fat and MUFAs (P < 0.05). Individuals in the highest tertiles of MDS had more consumption of nuts, fruits, fish, sea food, whole grains, vegetables, legumes, and MUFAs to SFAs ratio (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Higher consumption of legumes, MUFAs to SFAs ratio, fish/sea food, and nuts was inversely associated with T2D risk; HRs (95% CI) for T2D risk among those who had the highest adherence to these components of MDS were 0.56 (0.35−0.89), 0.41 (0.26−0.65), 0.55 (0.33−0.91), and 0.30 (0.18−0.50), respectively (Table 3). After adjustment for confounding variables, higher adherence to the MDS was associated with lower risk of T2D (HR = 0.48; 95% CI 0.27−0.83) (Table 4).

Discussion

A healthy diet decreases the risk of chronic diseases; e.g., diabetes and cardiovascular complications [23]. In this longitudinal cohort study, done among a Tehranian population, we showed higher MDS related to decreasing the risk of T2D.

Low physical activity as a risk factor for T2D was more prevalent among individuals with the highest MDS. Previous studies showed an inverse longitudinal relation between incidence of T2D and the MD [11,12,13, 24, 25]. In a trial study among individuals with diagnosis of T2D, compared to subjects with a low-fat diet, those with a low-carbohydrate Mediterranean diet, had a higher decline in HbA1C levels, and greater rate remission from diabetes [26]. However, contrary to our findings, a cohort study after 6.6 years of follow-up found no association between adherence to the MDS and risk of T2D [14]. The findings of a parallel controlled-feeding trial study reported that adherence to the MDS was not related with improvement in HOMA-IR [15].

Food items included in the Mediterranean diet as a healthy diet have a protective effect on T2D development by different mechanisms, including increased insulin sensitivity and decreased oxidative stress and inflammation [27]. This dietary pattern has a higher intake of unrefined cereals, fruits, legumes, vegetables, nuts, fish, and MUFA, but lower intakes of meat and SFAs [8]. As seen in Table 2, in the higher tertiles of Mediterranean diet scores, consumption of SFAs and MUFAs is significantly lower and higher, respectively. In our study, MUFAs to SFAs ratio was inversely associated with T2D risk, results that support previous findings indicating beneficial effects of high consumption of MUFAs and low intake of SFAs on insulin function and decrease the risk of T2D [28,29,30,31,32]. Similar to our findings, studies showed a protective effect of dietary intakes of fish [33], legumes [34, 35], and nuts [36] on diabetes; however, in contrast to our reports in a prospective cohort study, there was no association between nuts consumption and incident T2D [37]. Benefits of fish and sea food consumption in lowering the metabolic syndrome and T2D risk through anti-inflammatory mechanisms have been attributed to the omega-3 fatty acids [38, 39].

The Mediterranean diet has a reducing effect on some inflammatory markers such as adiponectin and C-reactive protein (CRP), and therefore, has important effects on the development of T2D [40]. However, data show that a dietary pattern with high intakes of fish, vegetables, and fruit, significantly decreased CRP [21]. Another possible mechanism for reducing the effect of Mediterranean diet on diabetes is for high content of antioxidants that have reducing effects on the stress of beta cell-impaired function and insulin resistance [14]. Because of the adverse effect of energy-dense foods on metabolic disorders and obesity, this dietary pattern has a protective effect on obesity, as a diabetes risk factor, by lower intake of energy due to high consumption of low energy density (fruit and vegetables) [41,42,43].

Of the strengths of this study, the current study has a long period of the follow-up. Of course, some limitations in our study need to be mentioned. First, in our study, during the follow-up, we observed a low incidence of T2D because of the young age of the individuals. Second, there was a lack of information on some confounder variables, such as income and occupation status of participants.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrate that higher adherence to the Mediterranean diet can be useful for prevention of T2D.

References

Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103:137–49.

Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1047–53.

Zhou B, Lu Y, Hajifathalian K, Bentham J, Di Cesare M, Danaei G. et al. Worldwide trends in diabetes since1980: a pooled analysis of 751 population-based studies with 4.4 million participants. Lancet.2016;387:1513–30.

Georgoulis M, Kontogianni MD, Yiannakouris N. Mediterranean diet and diabetes: prevention and treatment. Nutrients. 2014;6:1406–23.

Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Aunola S, Cepaitis Z, Hakumaki M, et al. Prevention of diabetes mellitus in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance in the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study: results from a randomized clinical trial. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:S108–113.

Sami W, Ansari T, Butt NS, Hamid MRA. Effect of diet on type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2017;11:65–71.

Bahadoran Z, Golzarand M, Mirmiran P, Saadati N, Azizi F. The association of dietary phytochemical index and cardiometabolic risk factors in adults: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2013;26(Suppl 1):145–53.

Willett WC, Sacks F, Trichopoulou A, Drescher G, Ferro-Luzzi A, Helsing E, et al. Mediterranean diet pyramid: a cultural model for healthy eating. Am J Clin Nutr. 1995;61:1402S–1406S.

Trichopoulou A, Costacou T, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and survival in a Greek population. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2599–608.

Boghossian NS, Yeung EH, Mumford SL, Zhang C, Gaskins AJ, Wactawski-Wende J, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and body fat distribution in reproductive aged women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67:289–94.

Salas-Salvado J, Bullo M, Babio N, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Ibarrola-Jurado N, Basora J, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with the Mediterranean diet: results of the PREDIMED-Reus nutrition intervention randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:14–19.

Martinez-Gonzalez MA, de la Fuente-Arrillaga C, Nunez-Cordoba JM, Basterra-Gortari FJ, Beunza JJ, Vazquez Z, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of developing diabetes: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336:1348–51.

Rossi M, Turati F, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Augustin LS, La Vecchia C, et al. Mediterranean diet and glycaemic load in relation to incidence of type 2 diabetes: results from the Greek cohort of the population-based European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Diabetologia. 2013;56:2405–13.

Abiemo EE, Alonso A, Nettleton JA, Steffen LM, Bertoni AG, Jain A, et al. Relationships of the Mediterranean dietary pattern with insulin resistance and diabetes incidence in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Br J Nutr. 2013;109:1490–7.

Bos MB, de Vries JH, Feskens EJ, van Dijk SJ, Hoelen DW, Siebelink E, et al. Effect of a high monounsaturated fatty acids diet and a Mediterranean diet on serum lipids and insulin sensitivity in adults with mild abdominal obesity. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;20:591–8.

Azizi F, Ghanbarian A, Momenan AA, Hadaegh F, Mirmiran P, Hedayati M, et al. Prevention of non-communicable disease in a population in nutrition transition: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study phase II. Trials. 2009;10:5.

Momenan AA, Delshad M, Sarbazi N, Ghaleh NR, Ghanbarian A, Azizi F. Reliability and validity of the modifiable activity questionnaire (MAQ) in an Iranian urban adult population. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15:279–82.

Hosseini-Esfahani F, Jessri M, Mirmiran P, Bastan S, Azizi F. Adherence to dietary recommendations and risk of metabolic syndrome: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Metabolism. 2010;59:1833–42.

Esfahani FH, Asghari G, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Reproducibility and relative validity of food group intake in a food frequency questionnaire developed for the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. J Epidemiol. 2010;20:150–8.

Samieri C, Grodstein F, Rosner BA, Kang JH, Cook NR, Manson JE, et al. Mediterranean diet and cognitive function in older age. Epidemiology. 2013;24:490–9.

Smidowicz A, Regula J. Effect of nutritional status and dietary patterns on human serum C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 concentrations. Adv Nutr. 2015;6:738–47.

Bozorgmanesh M, Hadaegh F, Ghaffari S, Harati H, Azizi F. A simple risk score effectively predicted type 2 diabetes in Iranian adult population: population-based cohort study. Eur J Public Health. 2011;21:554–9.

Bantle JP, Wylie-Rosett J, Albright AL, Apovian CM, Clark NG, Franz MJ, et al. Nutrition recommendations and interventions for diabetes--2006: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2140–57.

Romaguera D, Guevara M, Norat T, Langenberg C, Forouhi NG, Sharp S, et al. Mediterranean diet and type 2 diabetes risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study: the InterAct project. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1913–8.

Mozaffarian D, Marfisi R, Levantesi G, Silletta MG, Tavazzi L, Tognoni G, et al. Incidence of new-onset diabetes and impaired fasting glucose in patients with recent myocardial infarction and the effect of clinical and lifestyle risk factors. Lancet. 2007;370:667–75.

Esposito K, Maiorino MI, Petrizzo M, Bellastella G, Giugliano D. The effects of a Mediterranean diet on the need for diabetes drugs and remission of newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: follow-up of a randomized trial. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:1824–30.

Kastorini CM, Panagiotakos DB. Mediterranean diet and diabetes prevention: myth or fact? World J Diabetes. 2010;1:65–67.

Paniagua JA, de la Sacristana AG, Sanchez E, Romero I, Vidal-Puig A, Berral FJ, et al. A MUFA-rich diet improves posprandial glucose, lipid and GLP-1 responses in insulin-resistant subjects. J Am Coll Nutr. 2007;26:434–44.

Keapai W, Apichai S, Amornlerdpison D, Lailerd N. Evaluation of fish oil-rich in MUFAs for anti-diabetic and anti-inflammation potential in experimental type 2 diabetic rats. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2016;20:581–93.

Dai J, Jones DP, Goldberg J, Ziegler TR, Bostick RM, Wilson PW, et al. Association between adherence to the Mediterranean diet and oxidative stress. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1364–70.

Giugliano D, Esposito K. Mediterranean diet and metabolic diseases. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19:63–68.

Riserus U, Willett WC, Hu FB. Dietary fats and prevention of type 2 diabetes. Prog Lipid Res. 2009;48:44–51.

Rylander C, Sandanger TM, Engeset D, Lund E. Consumption of lean fish reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a prospective population based cohort study of Norwegian women. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e89845.

Becerra-Tomas N, Diaz-Lopez A, Rosique-Esteban N, Ros E, Buil-Cosiales P, Corella D. et al. Legume consumption is inversely associated with type 2 diabetes incidence in adults: a prospective assessment from the PREDIMED study. Clin Nutr. 2017;37:906–13.

Agrawal S, Ebrahim S. Association between legume intake and self-reported diabetes among adult men and women in India. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:706.

Asghari G, Ghorbani Z, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Nut consumption is associated with lower incidence of type 2 diabetes: the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Diabetes Metab. 2017;43:18–24.

Kochar J, Gaziano JM, Djousse L. Nut consumption and risk of type II diabetes in the Physicians’ Health Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64:75–79.

Marushka L, Batal M, David W, Schwartz H, Ing A, Fediuk K, et al. Association between fish consumption, dietary omega-3 fatty acids and persistent organic pollutants intake, and type 2 diabetes in 18 First Nations in Ontario, Canada. Environ Res. 2017;156:725–37.

Mirmiran P, Hosseinpour-Niazi S, Naderi Z, Bahadoran Z, Sadeghi M, Azizi F. Association between interaction and ratio of omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid and the metabolic syndrome in adults. Nutrition. 2012;28:856–63.

Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, Petrizzo M, Scappaticcio L, Giugliano D, Esposito K. Anti-inflammatory effect of Mediterranean diet in type 2 diabetes is durable: 8-year follow-up of a controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:e44–45.

Agnoli C, Sieri S, Ricceri F, Giraudo MT, Masala G, Assedi M, et al. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and long-term changes in weight and waist circumference in the EPIC-Italy cohort. Nutr Diabetes. 2018;8:22.

Mirmiran P, Bahadoran Z, Delshad H, Azizi F. Effects of energy-dense nutrient-poor snacks on the incidence of metabolic syndrome: a prospective approach in Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Nutrition. 2014;30:538–43.

Bahadoran Z, Mirmiran P, Delshad H, Azizi F. White rice consumption is a risk factor for metabolic syndrome in Tehrani adults: a prospective approach in Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Arch Iran Med. 2014;17:435–40.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate all the field investigators of the TLGS and participants of the cohort study for their valuable cooperation. We would like to thank Ms. Niloofar Shiva.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khalili-Moghadam, S., Mirmiran, P., Bahadoran, Z. et al. The Mediterranean diet and risk of type 2 diabetes in Iranian population. Eur J Clin Nutr 73, 72–78 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-018-0336-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41430-018-0336-2

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Healthy dietary pattern is associated with lower glycemia independently of the genetic risk of type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study in Finnish men

European Journal of Nutrition (2024)

-

Mediterranean dietary pattern and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies

European Journal of Nutrition (2022)

-

A cross-sectionally analysis of two dietary quality indices and the mental health profile in female adults

Current Psychology (2022)

-

Fruit and vegetable intake and risk of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: results from a 20-year long prospective cohort study in Swedish men and women

European Journal of Nutrition (2022)

-

Nutrition behaviour and compliance with the Mediterranean diet pyramid recommendations: an Italian survey-based study

Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity (2020)