Abstract

Background

Most studies examining post-menopausal menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) use and ovarian cancer risk have focused on White women and few have included Black women.

Methods

We evaluated MHT use and ovarian cancer risk in Black (n = 800 cases, 1783 controls) and White women (n = 2710 cases, 8556 controls), using data from the Ovarian Cancer in Women of African Ancestry consortium. Logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association of MHT use with ovarian cancer risk, examining histotype, MHT type and duration of use.

Results

Long-term MHT use, ≥10 years, was associated with an increased ovarian cancer risk for White women (OR = 1.38, 95%CI: 1.22–1.57) and the association was consistent for Black women (OR = 1.20, 95%CI: 0.81–1.78, pinteraction = 0.4). For White women, the associations between long-term unopposed estrogen or estrogen plus progesterone use and ovarian cancer risk were similar; the increased risk associated with long-term MHT use was confined to high-grade serous and endometroid tumors. Based on smaller numbers for Black women, the increased ovarian cancer risk associated with long-term MHT use was apparent for unopposed estrogen use and was predominately confined to other epithelial histotypes.

Conclusion

The association between long-term MHT use and ovarian cancer risk was consistent for Black and White women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer-related death in US women [1]. The incidence rate of ovarian cancer is lower in Black women (5.5 per 100,000) than in White women (6.7 per 100,000) [2], but Black women have lower five-year survival (38.3% in Black women vs. 45.5% in White women) [3]. Incidence and mortality rates of ovarian cancer have been declining, but the decline has been slower in Black women than in White women [4]. Ovarian cancer is a heterogeneous disease, with histotypes differing by molecular characteristics, etiology, and distribution of incidence and survival. High-grade serous carcinoma is the most common histotype of ovarian cancer ( ~63% of cases), followed by endometrioid ( ~10%), clear cell ( ~10%), mucinous ( ~9%), and low-grade serous ( ~3%) [5, 6].

Estrogen regulation plays a role in the etiology and progression of ovarian cancer, but may have differential effects by histotype [7, 8]. A decreased risk of ovarian cancer has been associated with hormonal and reproductive factors, including parity (all histotypes) [9], breastfeeding (high-grade serous, endometrioid, and clear cell tumors) [10], oral contraceptive use (high-grade serous, endometrioid, and clear cell tumors) [9], and tubal ligation (endometrioid and clear cell tumors) [9, 11]. The association between menopausal hormone therapy (MHT) use and ovarian cancer is inconsistent and debated [12, 13]. However, recent pooled and meta-analyses reported that MHT use was associated with an approximate 30% increased risk of ovarian cancer, with increased risk confined to high-grade serous and endometrioid tumor types [9, 12, 14, 15].

The majority of studies that have examined the MHT use–ovarian cancer risk association to date have focused predominately on White women, who have a higher prevalence of MHT use than Black women [16]. Three studies investigating this association in Black women have suggested that MHT use increases ovarian cancer risk [17,18,19], while another reported no association [20]. However, all prior studies of Black women included less than 70 exposed cases, resulting in wide confidence intervals, and the studies were underpowered to stratify by hysterectomy status or histotype. Thus, MHT use is a potentially important risk factor for ovarian cancer that has been underexplored for Black women; the generalizability of findings from studies comprised predominately of White women is unknown. The present study evaluated type and duration of MHT use in relation to ovarian cancer risk by histotype and hysterectomy status among Black and White women, using data from the Ovarian Cancer in Women of African Ancestry (OCWAA) consortium.

Methods

Study population

The OCWAA consortium was established to understand racial differences in risk factors for epithelial ovarian cancer. Participants in the present study are self-identified Black and White postmenopausal women from seven case-control and cohort studies whose data were harmonized in the OCWAA consortium [21]. Questionnaire, medical record, and tumor data were obtained from four case-control studies: the African American Cancer Epidemiology Study (AACES) [18], the Cook County Case-Control Study (CCCCS) [22, 23], the Los Angeles County Ovarian Cancer Study (LACOCS) [24], the North Carolina Ovarian Cancer Study (NCOCS) [25]; and in three case-control studies nested within prospective cohorts: the Black Women’s Health Study (BWHS) [17], the Multiethnic Cohort Study (MEC) [26], and the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) [27]. Each cohort study constructed a nested case-control study by selecting four to six controls per case. Eligible controls were alive at the time of case diagnosis and had at least one ovary. Controls were then matched within study to the case on race, age of case diagnosis, and last questionnaire completed prior to ovarian cancer diagnosis (index date). Data for time-varying exposures and covariates were taken from the questionnaire prior to the index date. Each study obtained informed consent from participants and was approved by the relevant Institutional Review Boards.

Outcome

Eligible cases were diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer (International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd ed. [ICD-O-3] topography code: C56.9). Diagnosis was verified through pathology reports. Tumor histology types (i.e., histotypes) were classified, as previously described [5, 6], as serous, endometrioid, clear cell, mucinous, and other epithelial. Cases with a serous histology were classified as low-grade or high-grade. High-grade endometrioid tumors were also classified as high-grade serous, as the majority of high-grade endometrioid carcinomas are biologically similar to high-grade serous carcinomas [28]. In a sensitivity analysis, high-grade endometroid cases were excluded. Prior analyses of MHT use and ovarian cancer risk have reported associations with high-grade serous and endometroid carcinomas, but not other histotypes [9, 12, 14, 15]. Due to a limited number of cases in Black women, clear cell, mucinous, and low-grade serous tumor types were collapsed with “other epithelial” histotypes for the primary analysis.

Exposure assessment

Each study collected data from participants at the time of the cases’ diagnosis (case-control studies) or from the questionnaire closest to the cases’ date of diagnosis (cohort studies) on MHT use via standardized questionnaires that were either interviewer-administered or self-administered. Harmonized variables were created by comparing questionnaires between the participating studies. MHT use was classified by type (unopposed estrogen MHT, estrogen-progesterone combination MHT, or estrogen-progesterone combination MHT after unopposed estrogen use), any use (ever, never), duration of use (never, < 5, 5 to < 10, ≥ 10 years), and recency of use (never, current, recent [< 5 years since use], former [≥ 5 years since use]). We excluded post-menopausal women with missing information on MHT use (5 Black cases, 23 Black controls, 3 White cases, and 12 White controls).

Statistical analyses

Logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association of MHT use with ovarian cancer risk by race. Race-specific ORs were stratified by histotype using polytomous regression models. P-values for heterogeneity were computed using Wald joint tests to compare the histotype-specific coefficients of each exposure. P-values for interaction between race and each exposure were assessed using likelihood ratio tests to compare regression models with and without a multiplicative term.

A test of study site heterogeneity was used to choose between common fixed effects or multi-level random effects estimators of pooled risk. Between study heterogeneity was based on the lower bound of 95% profile likelihood CI of τ2 > 0 and the I2 statistic [29]. No site heterogeneity was detected for any main exposure; thus, data were pooled for all analyses, and results are presented using fixed effects models.

Matching bias was adjusted for by controlling for matching factors common to all studies in the regression models; additionally, results were compared with more complex and computationally intensive methods (i.e., conditional logistic regression) to handling matching and any bias was determined to be negligible [30]. All models included terms for the matching factors of study site (AACES, CCCCS, LACOCS, NCOCS, BWHS, MEC, WHI), index year (year of case diagnosis), and age at index (continuous). We constructed a directed acyclic graph to select additional covariates for adjustment in the regression models: first degree family history of breast cancer (yes, no), first degree family history of ovarian cancer (yes, no), nulliparity (yes, no), education (GED or less/high school graduate, some college, college graduate, graduate/professional school), smoking status (ever, never), age at menopause (continuous), and premenopausal hysterectomy (yes, no).

Sensitivity analysis

As women who have had a premenopausal hysterectomy are often prescribed unopposed estrogen MHT, we conducted sensitivity analyses stratified by hysterectomy status. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

The present study included 800 Black ovarian cancer cases, 1783 Black controls, 2710 White cases, and 8556 White controls. Black women had a younger age at ovarian cancer diagnosis than White women (Table 1). Black women were more likely to have had a premenopausal hysterectomy than White women, while White women were more likely to be nulliparous. Black women were diagnosed with a higher proportion of endometrioid cases than White women (7.8 vs. 5.4%, respectively) and a lower proportion of clear cell cases (3.7 vs. 6.2%).

MHT use was more common in White women than in Black women (62.6 vs. 33.7% of control participants, respectively, used any MHT; Table S1). Among women who ever used MHT, White women reported longer duration of use than Black women (39.6% vs. 20.1% of controls participants, respectively, reported MHT use for ≥ 10 years). Ever use of MHT in Black women was not associated with risk of ovarian cancer overall (Table 2) or specific ovarian cancer histotypes (Table 3): high-grade serous, endometrioid, or other epithelial histotypes. However, based on larger numbers among White women, ever use was associated with an increased risk of high-grade serous ovarian cancer (OR = 1.28, 95% CI: 1.14–1.43) but inversely associated with other epithelial histotypes (OR = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.70–0.96).

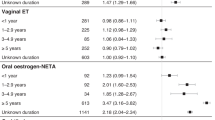

MHT use for ten or more years was associated with an increased ovarian cancer risk for White women (OR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.22–1.57, ptrend < 0.0001) and the association was consistent for Black women (OR = 1.20, 95% CI: 0.81–1.78, ptrend = 0.4, pinteraction = 0.4, Table 2). There was no evidence of heterogeneity between studies for Black women (I2 = 0.0%, pheterogeneity = 1.0) or White women (I2 = 35.6%, pheterogeneity = 0.2, Fig. 1). For White women, ten or more years of MHT use was associated with an increased risk of high-grade serous carcinoma (OR = 1.66, 95% CI: 1.43–1.92, ptrend < 0.0001) and endometroid tumors (OR = 1.38, 95% CI: 0.89–2.13, ptrend = 0.009, Table 3). For Black women, the increased risk associated with long-term use was confined to other histotypes (OR = 1.70, 95% CI: 0.97–2.99, ptrend = 0.07), with no association for high-grade serous carcinoma (OR = 1.08, 95% CI: 0.68–1.71, ptrend = 0.8) or endometroid tumors (OR = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.12–2.40, ptrend = 0.8). We interrogated this association with other epithelial histotypes further, by examining clear cell and mucinous tumors independent of other epithelial histotypes. Among Black women, ten or more years of MHT use was associated with elevated ORs for clear cell (OR = 1.93, 95% CI: 0.51–7.34, ptrend = 0.02) and mucinous tumors (OR = 2.17, 95% CI: 0.54–8.73, ptrend = 0.7), but CIs were wide and included the null as both histotypes only included three exposed cases. The association between ten or more years of MHT use and risk of other epithelial histotypes was attenuated after excluding the clear cell and mucinous tumors (OR = 1.60, 95% CI: 0.83–3.07, ptrend = 0.1), which included 14 exposed cases of other epithelial histotypes in Black women; these histotypes included six cases of carcinoma or adenocarcinoma, not otherwise specified (ICD-O-3 morphology codes: 8010 and 8140) and four cases of carcinosarcoma (8980 and 8951).

aORs are based on complete case analysis and adjusted for age at index (continuous), first degree family history of breast cancer (yes, no), first degree family history of ovarian cancer (yes, no), nulliparity (yes, no), education (high school graduate/GED or less, some college, college graduate, graduate/professional school), smoking status (ever, never), age at menopause (continuous), and pre-menopausal hysterectomy (yes, no).

Recent MHT use, within the past 5 years, was associated with elevated ORs for both Black and White women (OR = 1.23, 95% CI: 0.79–1.93 and OR = 1.18, 95% CI: 1.04–1.35, respectively), while MHT use that ended five or more years prior to diagnosis or index date had near null associations (OR = 1.00, 95% CI: 0.75–1.34 and OR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.86–1.12, respectively, Table 2). However, associations with recency of MHT use appeared to be due to longer duration of use (Table S2). Ten or more years of MHT use was associated with an increased ovarian cancer risk among current/recent MHT users and former MHT users for White women (OR = 1.41, 95% CI: 1.21–1.64 and OR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.22–1.78, respectively) and the associations were consistent for Black women (OR = 1.36, 95% CI: 0.78–2.37 and OR = 1.19, 95% CI: 0.61–2.32, respectively).

The associations between ten or more years of unopposed estrogen use and ovarian cancer risk were similar to the associations with ten or more years of any MHT, although stronger in magnitude, for both Black women (OR = 1.44, 95% CI: 0.92–2.25, ptrend = 0.05) and White women (OR = 1.61, 95% CI: 1.36–1.92, ptrend < 0.0001, Table 4). In White women, the association between ten or more years of estrogen plus progesterone use and ovarian cancer risk was similar to the association for ten or more years of unopposed estrogen use (OR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.12–1.58, ptrend = 0.0008). In Black women, no association between estrogen plus progesterone use and ovarian cancer risk was found, but data were sparse.

Among women who reported MHT use, 91% of Black women and 95% of White women with a hysterectomy used unopposed estrogens, compared to 48% of Black women and 53% of White women without a hysterectomy. When we examined the associations by hysterectomy status (Tables 5, 6), results were attenuated in women without a hysterectomy. In Black women, ten or more years of MHT use was associated with an elevated OR for women with a hysterectomy (OR = 1.40, 95% CI: 0.83–2.36, ptrend = 0.4, Table 5), but the OR was not elevated among women without a hysterectomy (OR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.48–1.79, ptrend = 0.8). In White women, ten or more years of MHT use was associated with an increased ovarian cancer risk for women with a hysterectomy (OR = 1.75, 95% CI: 1.30–2.37, ptrend < 0.0001, Table 6), but this association was attenuated among women without a hysterectomy (OR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.14–1.52, ptrend < 0.0001). Results were similar when we examined unopposed estrogen use only (Tables S3, S4). Results were also similar when we excluded high-grade endometroid cases from the analyses (Tables S5, S6).

Discussion

The OCWAA consortium leveraged seven U.S. studies of post-menopausal women to examine the MHT use-ovarian cancer association by race, accounting for histotype and hysterectomy status. Use of MHT for 10 or more years was associated with a 20–38% increased ovarian cancer risk, which was consistent for Black and White women.

This study extends prior knowledge with a more comprehensive examination of the MHT–ovarian cancer risk association in U.S. Black women. The similarity of the associations for duration of use and ovarian cancer risk for Black and White women suggests that the extensive prior literature on this topic, which has been primarily conducted in populations of White women, may extend to Black women. The majority of epidemiologic studies have reported that unopposed estrogen use increases ovarian cancer risk [12, 14, 15], but the association with estrogen plus progesterone use is less clear. One recent pooled analysis suggested that estrogen plus progesterone use increased ovarian cancer risk [12], while another pooled study found no associations with ovarian cancer risk [31]. In the current study, unopposed estrogen use was associated with an increased ovarian cancer risk in both Black and White women. Estrogen plus progesterone use was associated with an increased ovarian cancer risk in White women, but estrogen plus progesterone use was too infrequent for informative analysis among the Black women. Similar to the results from our study, most prior studies have noted that an increased risk of ovarian cancer associated with MHT use is primarily seen in long-term users (defined by most studies as ≥ 5 years of use) [9, 12, 32, 33], providing some reassurance about little to no increased ovarian cancer risk for women who use MHTs for short durations. Further, the association between short duration of MHT use and ovarian cancer is susceptible to reverse causation [13], which is less likely an explanation for an association between longer term MHT use and ovarian cancer as we see in the current study.

Recent pooled and meta-analyses that have examined ovarian cancer histotypes have reported that MHT use was associated with an increased risk of serous and endometrioid tumor histotypes [9, 12, 14, 15]. No association—or an inverse association—has been reported between MHT use and clear cell, mucinous, and other epithelial histotypes. Our results among White women were consistent with the prior reports: Ten or more years of MHT use was associated with a 38–66% increased risk of high-grade serous and endometrioid tumors, but there was no association with other epithelial histotypes. However, our results among Black women were the opposite: Ten or more years of MHT use was associated with a 70% increased risk of other epithelial histotypes, but there was little to no association with high-grade serous or endometrioid tumors. We further assessed this association by examining clear cell and mucinous tumors independent of other epithelial histotypes. Although the sample sizes were limited, the ORs remained elevated for clear cell tumors, mucinous tumors, and all other epithelial histotypes.

Following the results from the WHI randomized controlled trial [34, 35], which reported MHT use was associated with an increased risk of breast cancer and cardiovascular disease, MHT use decreased in all racial/ethnic groups [16]. Although indications for MHT use, including hysterectomy and vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause, are more common in Black women than White women [36,37,38,39,40], use of MHT remains about twice as high among White women as compared to Black women [16]. In our study’s control participants, 63% of White women reported MHT use compared to 34% of Black women. The lower prevalence of MHT use in Black women makes examining the MHT use–ovarian cancer association challenging in individual studies. Three studies (AACES, NCOCS, and BWHS, which are all included in OCWAA), previously reported that MHT use is associated with an increased ovarian cancer risk in Black women [17,18,19], but power was limited. Additionally, these prior studies were unable to examine potential differences in the MHT use–ovarian cancer association by race, as they were either underpowered to stratify by race [19] or included only Black women [17, 18]. MEC was able to stratify by race and reported no association between MHT use and ovarian cancer for White or Black women [20]. However, the study included only 132 White and 83 Black post-menopausal ovarian cancer cases.

Cellular studies support the hypothesis that estrogens influence ovarian cancer risk [8]. Estrogen binds to estrogen receptor-α, which leads to activation of estrogen-responsive genes including proto-oncogenes. In turn, these genes signal cellular proliferation and differentiation [8, 41]. Independent of estrogen receptor pathways, metabolic activation of estrogens can result in formation of free radicals and mutagenic DNA adducts, leading to mutations and subsequent neoplastic transformation of proliferating cells [8, 42, 43]. Epidemiologic studies have consistently shown that surrogates for a lower lifetime endogenous estrogen exposure (i.e., parity, breastfeeding, tubal ligation, and oral contraceptive use) are associated with a decreased ovarian cancer risk [9,10,11]. However, studies of endogenous circulating sex steroid hormones have reported null associations between estrogen metabolites and risk of ovarian cancer when not evaluated by subtype [44,45,46]. Recent studies have shown an association between estrogen metabolites and an increased risk of non-serous ovarian cancer, both among MHT users [7] and non-users [47]. This is in contrast to the current study and prior literature, which suggests that exogenous unopposed estrogen use increases the risk of serous and some non-serous histotypes of ovarian cancer.

Limitations of the present study include potential inaccuracies in exposure capture and recall bias. MHT use in the included studies was all self-reported and may not have been reported accurately compared to pharmaceutical records. However, in a study from Sweden with prescription drug linkage, longer duration MHT use was also associated with increased ovarian cancer risk [48], but there was no assessment of specific MHT formulations. Recall bias was not a concern for the cases and controls nested within prospective cohort studies (BWHS, MEC, WHI), but recall bias may be a concern for case-control studies, particularly those conducted following the report of results on associations of MHT with increased risk of some disease outcomes in 2002 from the WHI hormone trials [34, 35]. However, as shown in the forest plot, our results are consistent between the cohort and case-control studies.

Strengths of our study include the larger number of Black women than in previous studies. The OCWAA consortium provided greater statistical power than any prior study to examine the association between MHT use and ovarian cancer risk for Black women, allowing examination by histotype and hysterectomy status. However, the number of Black women in these stratified analyses was still often small. The OCWAA consortium harmonized the covariates across the included studies, which has an advantage over a meta-analytic type of approach by allowing for uniform adjustment for potential confounders. Our approach allowed for examination of study heterogeneity and racial differences in associations.

In conclusion, long-term use of MHTs, particularly unopposed estrogen use, was associated with an increased ovarian cancer risk in the OCWAA consortium for White women and the association was consistent for Black women. Further research is needed to assess estrogen plus progesterone use in Black women, specific MHT formulations (e.g., bioidentical estrogens vs. animal-derived estrogens), and associations with ovarian cancer histotypes. Since the OCWAA consortium was designed to examine racial differences in ovarian cancer risk factors between Black and White women, this study was unable to examine the association between MHT use and ovarian cancer for additional underrepresented racial/ethnic populations. Studies of MHT and ovarian cancer are needed for such populations.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the OCWAA Consortium.

References

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures. (2021).

National Program of Cancer Registries and Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program SEER*Stat Database: NPCR and SEER Incidence - U.S. Cancer Statistics Public Use Research Database, 2020 Submission (2001-2018). United States Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. Released June 2021. Accessed at www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/public-use.

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER Research Data, 18 Registries, Nov 2020 Sub (2000-2018) - Linked To County Attributes - Time Dependent (1990-2018) Income/Rurality, 1969-2019 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, released April 2021, based on the November 2020 submission.

Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse SF, et al. (eds). SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2012, National Cancer Institute. Bethesda, MD, https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2012/, based on November 2014 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2015.

Peres LC, Cushing-Haugen KL, Kobel M, Harris HR, Berchuck A, Rossing MA, et al. Invasive Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Survival by Histotype and Disease Stage. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111:60–68.

Kurman, RJ, International Agency for Research on Cancer. & World Health Organization. WHO classification of tumours of female reproductive organs. 4th edn, (International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, 2014).

Trabert B, Coburn SB, Falk RT, Manson JE, Brinton LA, Gass ML, et al. Circulating estrogens and postmenopausal ovarian and endometrial cancer risk among current hormone users in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Cancer Causes Control. 2019;30:1201–11.

Mungenast F, Thalhammer T. Estrogen biosynthesis and action in ovarian cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2014;5:192.

Wentzensen N, Poole EM, Trabert B, White E, Arslan AA, Patel AV, et al. Ovarian Cancer Risk Factors by Histologic Subtype: An Analysis From the Ovarian Cancer Cohort Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2888–98.

Babic A, Sasamoto N, Rosner BA, Tworoger SS, Jordan SJ, Risch HA, et al. Association Between Breastfeeding and Ovarian Cancer Risk. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:e200421.

Tworoger, SS, Shafrir, AL & Hankinson, SE Ovarian Cancer. In: Michael J Thun, et al. (eds). Schottenfeld and Fraumeni cancer epidemiology and prevention Ch. 46, xix, 1308 pages (Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2018).

Collaborative Group On Epidemiological Studies Of Ovarian, C., Beral V, Gaitskell K, Hermon C, Moser K, Reeves G, et al. Menopausal hormone use and ovarian cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis of 52 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 2015;385:1835–42.

Shapiro S, Stevenson JC, Mueck AO, Baber R. Misrepresentation of the risk of ovarian cancer among women using menopausal hormones. Spurious findings in a meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2015;81:323–6.

Liu Y, Ma L, Yang X, Bie J, Li D, Sun C, et al. Menopausal hormone replacement therapy and the risk of ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:801.

Lee AW, Ness RB, Roman LD, Terry KL, Schildkraut JM, Chang-Claude J, et al. Association between menopausal estrogen-only therapy and ovarian carcinoma risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:828–36.

Sprague BL, Trentham-Dietz A, Cronin KA. A sustained decline in postmenopausal hormone use: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:595–603.

Bethea TN, Palmer JR, Adams-Campbell LL, Rosenberg L. A prospective study of reproductive factors and exogenous hormone use in relation to ovarian cancer risk among Black women. Cancer Causes Control. 2017;28:385–91.

Schildkraut JM, Alberg AJ, Bandera EV, Barnholtz-Sloan J, Bondy M, Cote ML, et al. A multi-center population-based case-control study of ovarian cancer in African-American women: the African American Cancer Epidemiology Study (AACES). BMC Cancer. 2014;14:688.

Moorman PG, Palmieri RT, Akushevich L, Berchuck A, Schildkraut JM. Ovarian cancer risk factors in African-American and white women. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:598–606.

Sarink D, Wu AH, Le Marchand L, White KK, Park SY, Setiawan VW, et al. Racial/Ethnic Differences in Ovarian Cancer Risk: Results from the Multiethnic Cohort Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29:2019–25.

Schildkraut JM, Peres LC, Bethea TN, Camacho F, Chyn D, Cloyd EK, et al. Ovarian Cancer in Women of African Ancestry (OCWAA) consortium: a resource of harmonized data from eight epidemiologic studies of African American and white women. Cancer Causes Control. 2019;30:967–78.

Kim S, Dolecek TA, Davis FG. Racial differences in stage at diagnosis and survival from epithelial ovarian cancer: a fundamental cause of disease approach. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71:274–81.

Peterson CE, Rauscher GH, Johnson TP, Kirschner CV, Barrett RE, Kim S, et al. The association between neighborhood socioeconomic status and ovarian cancer tumor characteristics. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:633–7.

Wu AH, Pearce CL, Tseng CC, Templeman C, Pike MC. Markers of inflammation and risk of ovarian cancer in Los Angeles County. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1409–15.

Schildkraut JM, Moorman PG, Halabi S, Calingaert B, Marks JR, Berchuck A. Analgesic drug use and risk of ovarian cancer. Epidemiology. 2006;17:104–7.

Kolonel LN, Henderson BE, Hankin JH, Nomura AM, Wilkens LR, Pike MC, et al. A multiethnic cohort in Hawaii and Los Angeles: baseline characteristics. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151:346–57.

Hays J, Hunt JR, Hubbell FA, Anderson GL, Limacher M, Allen C, et al. The Women’s Health Initiative recruitment methods and results. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:S18–77.

Clarke AA, Gilks B. Ovarian Carcinoma: Recent Developments in Classification of Tumour Histological Subtype. Can J Pathology. 2011;3:33–42.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60.

Kuo CL, Duan Y, Grady J. Unconditional or Conditional Logistic Regression Model for Age-Matched Case-Control Data? Front Public Health. 2018;6:57.

Lee AW, Wu AH, Wiensch A, Mukherjee B, Terry KL, Harris HR, et al. Estrogen Plus Progestin Hormone Therapy and Ovarian Cancer: A Complicated Relationship Explored. Epidemiology. 2020;31:402–8.

Fortner RT, Rice MS, Knutsen SF, Orlich MJ, Visvanathan K, Patel AV, et al. Ovarian Cancer Risk Factor Associations by Primary Anatomic Site: The Ovarian Cancer Cohort Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29:2010–8.

Trabert B, Wentzensen N, Yang HP, Sherman ME, Hollenbeck A, Danforth KN, et al. Ovarian cancer and menopausal hormone therapy in the NIH-AARP diet and health study. Br J Cancer. 2012;107:1181–7.

Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, LaCroix AZ, Kooperberg C, Stefanick ML, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–33.

Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black H, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701–12.

Kjerulff KH, Guzinski GM, Langenberg PW, Stolley PD, Moye NE, Kazandjian VA. Hysterectomy and race. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:757–64.

Bower JK, Schreiner PJ, Sternfeld B, Lewis CE. Black-White differences in hysterectomy prevalence: the CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:300–7.

Gartner DR, Delamater PL, Hummer RA, Lund JL, Pence BW, Robinson WR. Integrating Surveillance Data to Estimate Race/Ethnicity-specific Hysterectomy Inequalities Among Reproductive-aged Women: Who’s at Risk? Epidemiology. 2020;31:385–92.

Adam EE, White MC, Saraiya M. US hysterectomy prevalence by age, race and ethnicity from BRFSS and NHIS: implications for analyses of cervical and uterine cancer rates. Cancer Causes Control. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-021-01496-0.

Gold EB, Colvin A, Avis N, Bromberger J, Greendale GA, Powell L, et al. Longitudinal analysis of the association between vasomotor symptoms and race/ethnicity across the menopausal transition: study of women’s health across the nation. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1226–35.

Chang CY, McDonnell DP. Molecular pathways: the metabolic regulator estrogen-related receptor alpha as a therapeutic target in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:6089–95.

Cavalieri EL, Rogan EG. Unbalanced metabolism of endogenous estrogens in the etiology and prevention of human cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2011;125:169–80.

Yager JD. Mechanisms of estrogen carcinogenesis: The role of E2/E1-quinone metabolites suggests new approaches to preventive intervention–A review. Steroids. 2015;99:56–60.

Helzlsouer KJ, Alberg AJ, Gordon GB, Longcope C, Bush TL, Hoffman SC, et al. Serum gonadotropins and steroid hormones and the development of ovarian cancer. JAMA. 1995;274:1926–30.

Lukanova A, Lundin E, Akhmedkhanov A, Micheli A, Rinaldi S, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, et al. Circulating levels of sex steroid hormones and risk of ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2003;104:636–42.

Dallal CM, Lacey JV Jr., Pfeiffer RM, Bauer DC, Falk RT, Buist DS, et al. Estrogen Metabolism and Risk of Postmenopausal Endometrial and Ovarian Cancer: the B approximately FIT Cohort. Horm Cancer. 2016;7:49–64.

Trabert B, Brinton LA, Anderson GL, Pfeiffer RM, Falk RT, Strickler HD, et al. Circulating Estrogens and Postmenopausal Ovarian Cancer Risk in the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2016;25:648–56.

Morch LS, Lokkegaard E, Andreasen AH, Kruger-Kjaer S, Lidegaard O. Hormone therapy and ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2009;302:298–305.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the WHI investigators and staff for their dedication, and the study participants for making the study possible. A full listing of WHI investigators can be found at: https://www.whi.org/doc/WHI-Investigator-Long-List.pdf. Pathology data were obtained from the following state cancer registries (AZ, CA, CO, CT, DE, DC, FL, GA, IL, IN, KY, LA, MD, MA, MI, NJ, NY, NC, OK, PA, SC, TN, TX, VA), and results reported do not necessarily represent their views. The IRBs of participating institutions and cancer registries have approved these studies, as required. Opinions expressed by the authors are their own and this material should not be interpreted as representing the official viewpoint of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health, or the National Cancer Institute.

Funding

The OCWAA Consortium is funded by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA207260), and the individual studies in the OCWAA Consortium received funding from several Institutes in the National Institutes of Health: R01CA142081 for AACES; R01CA058420, UM1CA164974, U01CA164974 for BWHS; P60MD003424 for CCCCS; N01CN025403, P01CA17054, P30CA14089, R01CA61132, N01PC67010, R03CA113148, R03CA115195 for LACOCS; U01CA164973 for MEC; and R01CA76016 for NCOCS. The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through contracts HHSN268201600001C, HHSN268201100046C, HHSN268201100001C, HHSN268201100002C, HHSN268201100003C, HHSN268201100004C, and HHSN271201100004C. Peres and Bethea are additionally supported by the National Cancer Institute (R00 CA218681 (Peres); K01 CA212056 (Bethea)); Petrick is supported by the Karin Grunebaum Cancer Research Foundation and the Boston University Peter Paul Career Development Professorship. The funders did not play a role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: JMS, LR, CEJ, LCP, JLP. Data curation: CEJ, EVB, TNB, ABF, HRH, PGM, EM, HMO, VWS, AHW, LR, JMS. Formal Analysis: CEJ, TFC, WR. Funding acquisition: JMS, LR. Methodology: JMS, LR, CEJ, LCP, MEB, JLP. Critical revision and interpterion: All authors. Writing – original draft: JLP, LR. Writing – critical revision & editing: All authors. Approval of final manuscript: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

ME Barnard reports personal fees from Epi Excellence LLC outside of the submitted work. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Each study obtained informed consent from its participants; the individual studies and the OCWAA Consortium were approved by the relevant Institutional Review Boards.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Petrick, J.L., Joslin, C.E., Johnson, C.E. et al. Menopausal hormone therapy use and risk of ovarian cancer by race: the ovarian cancer in women of African ancestry consortium. Br J Cancer 129, 1956–1967 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-023-02407-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-023-02407-7

- Springer Nature Limited