Abstract

Background

COVID-19 pandemic introduced significant challenges that may have exacerbated healthcare worker (HCW) burnout. To date, assessments of burnout during COVID-19 pandemic have been cross-sectional, limiting our understanding of changes in burnout. This longitudinal study assessed change across time in pediatric HCW burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic and whether demographic and psychological factors were associated with changes in burnout.

Methods

This longitudinal study included 162 physicians, physician assistants, nurses, and medical technicians within the emergency department (ED), intensive care, perioperative, and inter-hospital transport services in a children’s hospital. HCW demographics, anxiety and personality traits were reported via validated measures. HCWs completed the Maslach Burnout Inventory in April 2020 and March 2021. Data were analyzed using generalized estimating equations.

Results

The percentage of HCWs reporting high emotional exhaustion and/or depersonalization burnout increased significantly across time (18.5% to 28.4%, P = 0.010). Factors associated with increased emotional exhaustion included working in the ED (P = 0.011) or perioperative department (P < 0.001), being a nurse or medical technician (P’s < 0.001), not having children (P < 0.001), and low conscientiousness (P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Pediatric HCW burnout significantly increased over 11-months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Results suggest that certain demographic and psychological factors may represent potential area to target for intervention for future pandemics.

Impact

-

This longitudinal study revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on pediatric healthcare worker burnout.

-

The percentage of healthcare workers reporting high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization burnout increased significantly over 11-months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

Results suggest that certain demographic and psychological factors may represent potential targets for future interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Burnout in healthcare is a growing concern with current data estimating that 30–70% of healthcare providers experience burnout.1,2,3,4 Prevalence of burnout is similar in pediatric care settings, with data indicating that 20–67% of pediatric healthcare workers (HCWs), including physicians, nurses, and support staff report experiencing burnout.1,4,5,6,7,8 According to the multidimensional theory of burnout, burnout is an individual experience of work- or care-related stress that occurs within a social context and has three components: emotional exhaustion, an impersonal attitude, and a decreased sense of personal competence.9 HCW burnout can result in a host of negative professional and personal consequences including poor clinical care, patient satisfaction, and HCW mental and physical health.2,10,11,12,13,14,15 Previous work has collectively identified certain demographic (younger age, female, unmarried), occupational (less experience, high-acuity setting, workload), professional role (nurses, technicians), and psychological (anxiety, depression) factors associated with higher levels of burnout.3,4,8,15,16,17

The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced significant clinical care and personal safety challenges that may exacerbate levels of burnout in HCWs.18 A recent review on physician psychological symptoms during infectious disease outbreaks, including COVID-19, reported burnout prevalence rates up to 75%.19 Results from cross-sectional studies assessing burnout during COVID-19 specifically indicate that United States HCWs may be experiencing higher levels of burnout compared to those in other countrie,20,21,22 and data suggest that social isolation, work experience, and contact with COVID-19 patients may be associated with higher levels of burnout.22,23,24,25,26

To date, limited longitudinal data exist on burnout HCW during the COVID-19 pandemic and most of the existing data were collected early in the first year of the pandemic. Longitudinal assessments of burnout may help us better understand the impact of the pandemic on HCWs and, importantly, identify risk and protective factors associated with burnout trajectory.

The objective of the current study was to conduct a longitudinal assessment of burnout among pediatric HCWs from April 2020 to March 2021. We aimed to assess whether there was a change in pediatric HCW burnout over an eleven-month period during the COVID-19 pandemic and identify demographic and psychological factors associated with change in burnout. Informed by the multidimensional theory of burnout and by previous results from cross-sectional studies of HCW burnout, we hypothesized that years of experience,5,15 parental status,3 anxiety,19,22 and conscientious27 and neuroticism personality characteristics27,28 would be associated with changes in burnout.

Methods

Design/Participants

The current study employed a longitudinal, observational study design to assess change in burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study included a convenience sample of HCWs enrolled in a larger longitudinal study29,30 assessing COVID-19 antibody seroprevalence in HCWs at a quaternary care pediatric hospital in Orange, California USA. Participants of the study included attending physicians, physician assistants (PAs), nurse practitioners (NPs), registered nurses (RNs), and medical technicians with direct patient contact in the emergency department (ED), pediatric intensive care unit, perioperative services, and the inter-hospital transport services teams. Results of this the larger seroprevalence study were previously reported elsewhere.29,30 This present analysis focuses only on a sub-sample of HCWs who were given and completed burnout measures on April 2020 (Time 1) and March 2021 (Time 2). Results included in this report were not published previously.

Measures

Demographics and occupation

A demographics questionnaire assessed HCWs self-reported age, sex, race, marital status, number of children, job position, and years of experience (post-training).

Personality

The Big Five Inventory31 assessed the ‘Big Five’ dimensions of personality: openness (sample α = 0.66), conscientiousness (sample α = 0.69), extraversion (sample α = 0.762), agreeableness (sample α = 0.77), and neuroticism (sample α = 0.78). This 44-item measure is widely used to assess personality, has demonstrated reliability and validity across large international adult samples, and has been used in health care worker samples.27,32,33 The personality dimension subscale average scores were used for analyses.

Anxiety

HCW trait anxiety was assessed via the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), which is a 20- item self-report measure used to assess adult general (trait) anxiety. The STAI is considered a gold standard measurement for anxiety, demonstrating good reliability and validity in diverse adult samples and health care workers.34,35,36,37,38 A cut-off score of 4039 has been utilized to detect clinically significant symptoms of anxiety. The total and cut-off scores were used in analyses (α = 0.87).

Primary outcome

Burnout

Maslach Burnout Inventory – Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS)11 is the most widely accepted measure for the assessment of burnout in health care workers and has demonstrated validity across international samples of health care workers.40,41,42,43 This measure assesses three dimensions of burnout in healthcare service workers: emotional exhaustion (i.e., feelings of being emotionally overextended by one’s work), depersonalization (i.e., an impersonal response to one’s service or responsibilities), and personal accomplishment (i.e., feelings of competence and successful achievement in one’s work with people) dimensions of burnout. Each of the 22 items are rated on a seven-point Likert-type scale ranging from never to everyday. Higher emotional exhaustion and depersonalization scores reflect higher burnout within those dimensions whereas lower personal accomplishment scores reflect higher burnout within the personal accomplishment burnout dimension. The MBI-HSS authors recommend utilizing continuous total scores for each burnout dimension when examining predictors or outcomes of burnout, but low, moderate and high population norms can be used to characterize levels of burnout across samples.11,44,45 This study utilized both the continuous total emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment scores and characterized burnout dimension scores into low, moderate, and high levels based on published norms.11 Sample Cronbach’s alphas for Emotional Exhaustion, Depersonalization and Personal Accomplishment were 0.89, 0.71, and 0.80, respectively.

Procedures

Study data were collected during the spring of 2020 (April–May; Time 1) and in March 2021 (Time 2) as part of a larger study examining seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in HCWs.29,30 HCWs were recruited via department-wide emails and interested HCWs completed informed consent. At Time 1, selected participants completed demographics and the first burnout assessment. At Time 2, those participants completed the second burnout assessment and personality and anxiety questionnaires. Participant questionnaires were administered via REDCap. Ethical approval for all study procedures was obtained from the Children’s Hospital of Orange County Institutional Review Board (# 200452).

Data analyses

Study participants were described by percentage with defined trait for categorical and by mean (SD) for continuous factors. Burnout outcomes were described by mean (SD) and categorically (percent low, moderate, and high) at Time 1 and Time 2. Based on normative data,11 the interpretation of the total subscale scores are as follows: emotional exhaustion low 0–16, moderate 17–26, high 27–54; depersonalization low 0–6, moderate 7–12, high 13–35; personal accomplishment (lower scores reflect higher burnout) low 0–31, moderate 32–38, high 39–48. To aide in the comparison of current sample burnout levels to other health care provider samples,3,46,47 categorical burnout data for those that endorsed high emotional exhaustion and/or depersonalization burnout are also reported. When <10% of items were missing on any measure subscale, the value was imputed based on mean of remaining items. Imputation was required in less than 5% (n = 6) of participants. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) analyses with specification of repeat measures and exchangeable correlation structure assessed significance of change across time in burnout scale scores. In the GEE analyses, distribution specification was determined by parameterization of outcome (binomial, ordinal, or linear). For burnout subscales that demonstrated a significant change from Time 1 to Time 2, bivariate analyses examined whether change in average burnout scale scores were associated with HCW demographics and occupational and psychological characteristics. Multivariate analyses were used to model the composite of risk and protective factors that contributed to change in burnout using a stepwise procedure. Each factor and interaction with time was stepped into the multivariate model in order of significance in the bivariate examination. Factors were retained in the final model when their interaction with time was significant at the 0.05 level. The study sample size of 162 participants provided 99.0% power to detect the average difference of 3.3 points (SD = 9.7) in our primary outcome of pediatric HCW’s burnout from emotional exhaustion at the 0.05 level of significance. Analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY:IBM Corp.

Results

A total of 863-institution wide HCWs were emailed about the study and enrollment was discontinued at 382 due to availability of testing resources for the larger seroprevalence study.29,30 Out of the 382 participants that completed study measures at Time 1 (T1), 162 (42.4%) completed measures at Time 2 (T2). Sample demographics and descriptive statistics for participants that completed measures at T1 and T2 are presented in Table 1. It is important to note that T1 emotional exhaustion (t = –0.77, P > 0.05) and depersonalization burnout (t = –1.34, P > 0.05) did not significantly differ between the HCWs who completed only T1 and the HCWs who completed T1 and T2.

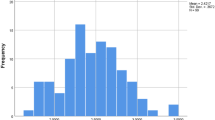

From T1 to T2, we observed a significant increase in the percentage of HCWs endorsing high levels of emotional exhaustion and/or high levels of depersonalization burnout from T1 to T2 (18.5% vs. 28.4%, P = 0.01; Fig. 1). There was also a significant increase in both emotional exhaustion and depersonalization total burnout scores (Table 2 and Table 3, respectively). Personal accomplishment burnout did not significantly change from T1 (40.0, 95% CI 39.0–41.1) to T2 (39.2, 95% CI 38.2–40.3; P = 0.08).

HCW characteristics and change in emotional exhaustion burnout

As shown in Table 2, results from bivariate analyses revealed that demographic variables such as age (P < 0.001), job position (P = 0.008), and years of experience (P < 0.001), and psychological variables such as conscientiousness personality (P = 0.041) and anxiety (P = 0.016) factors were significantly associated with increases in emotional exhaustion burnout.

In the final multivariate model (see Table 4), certain job professions (i.e., nurse or technician; P’s < 0.001), departments (i.e., ED [P = 0.011] or perioperative [P < .001]), and conscientiousness personality (P = 0.030) were found to be independent contributing factors to change in emotional exhaustion burnout. In HCWs that endorsed low conscientiousness, average emotional exhaustion increased from low to moderate burnout levels (+7.2, 95% CI 3.3–11.0, P < 0.001).

HCW characteristics and change in depersonalization burnout

Bivariate analyses for depersonalization burnout also indicated that both demographic (HCW age, marital status, parental status, job position, and years of experience) and psychological (conscientiousness, agreeableness, and neuroticism personality) factors were associated with a significant increase in depersonalization burnout from T1 to T2 (see Table 3).

In the multivariate model (Table 4), younger age (P < 0.001) and working within the intensive care (P = 0.008) or perioperative departments (P = 0.012) were the only demographic characteristics that were independently associated with change in depersonalization burnout. Lower agreeableness (P = 0.004) and higher neuroticism personality traits were also significant independent contributing factors to change in depersonalization burnout, with higher neuroticism contributing to an increase in depersonalization burnout from low to moderate levels (+3.1, 95% CI 0.80–5.40, P = 0.008).

Discussion

Under the conditions of this study, we found that the percentage of HCWs reporting high emotional exhaustion and/or depersonalization burnout increased significantly from 18.5% to 28.4% during an 11-month period of the COVID-19 pandemic. The theoretical contribution of this manuscript is that we have identified a number of factors that are associated with increased emotional exhaustion or depersonalization burnout such as unit in the hospital, function in the hospital, family status, low conscientiousness, low agreeableness and high neuroticism. While many of these predictive variables have only theoretical implications, some have contribution for the practitioners and hospital administration. For example, while one is not likely to change their role or unit in the hospital, it is the case that if hospital administration is aware of this increased risk, they can provide more resources to these personnel. Similarly, more psychological support and intervention may be especially beneficial for those who score high on neuroticism and for those who scored low conscientiousness there is a need for more support to address challenges surrounding prioritizing tasks and assertiveness.

Factors independently associated with emotional exhaustion burnout included being in a nursing or medical technician role, not having children, and low conscientiousness. The emotional exhaustion dimension of burnout reflects feeling emotionally overextended and fatigued by one’s work. Having a family may have offered additional emotional support outside of work3,16,24,48 and working in a more senior role, non-support position may have afforded more autonomy and control1,49 to protect against the emotional toll of working in a healthcare setting during the pandemic. Further, high conscientiousness, a trait that reflects a tendency to be responsible, organized, and industrious, may have been protective against feeling emotionally depleted in the context of COVID-19-related clinical care challenges. Cross-sectional studies have also shown a beneficial effect of conscientiousness on burnout,27 and current results suggest that characteristics reflective of this personality trait may have a prolonged protective effect.

Younger age, low agreeableness and high neuroticism were each independently associated with increased depersonalization burnout. Depersonalization is indicative of a more interpersonal component of burnout and reflects an impersonal response to one’s service or responsibilities and the development of a more negative or callous attitude. Study findings align with previous cross-sectional work indicating that high neuroticism and low agreeableness are associated with higher depersonalization burnout.5,27,28,48 Attributes associated with agreeableness including compassion, trust and respectfulness may have contributed to lower levels of interpersonal detachment while navigating fluctuating clinical and personal stressors during the pandemic. Neuroticism, on the other hand, is characterized by emotional instability and more intense negative affect. HCWs high on this trait may have had increased difficulty navigating exposure to uncertainty and stressors throughout the pandemic and subsequent negative emotional responses and volatility may have contributed to interpersonal challenges and detachment. Studies conducted prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic have also reported that older age is associated with lower risk for HCW burnout more generally and have suggested that training and experience may play a role in this association.5,15 Years of experience did not remain a significant contributor to change in burnout in our study, however the association between age and depersonalization burnout may reflect related factors such as time within in the institution and/or current role, with older HCWs potentially having more seniority with regards to scheduling and more time within their departments to build interpersonal relationships.

This study identified demographic and psychological factors unique to the individual HCW (i.e., age, family, personality characteristics) as well as those pertaining to the work environment and occupational role (i.e., department, job position) that may independently contribute to changes in burnout in the context of a stressor such as a pandemic. These findings are relatively consistent with past cross-sectional studies conducted prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic that have reported higher burnout in HCWs that do not have children and endorse less support from family, less experience, and lower conscientiousness and agreeableness.3,4,5,49,50 The longitudinal methodology of the current study, conducted over approximately one-year of the COVID-19 pandemic, builds on past work by providing important data on the changes in HCW burnout during the pandemic and multiple potential targets for intervention.

Interventions and workplace health promotion programs aimed at early identification as well as offering emotional support and enhancing appropriate coping skills (e.g., mindfulness) have shown promise in minimizing burnout and preventing negative long-term outcomes.51,52 Given the current results, access to these interventions may be especially important for HCWs in lower-level, support roles and those working in high acuity departments. HCW personality traits and associated characteristics can change over time and in response to training or intervention.53,54,55 Thus, the assessment of HCW personality, and subsequent identification of potentially protective and detrimental characteristics, may also further direct intervention efforts to mitigate burnout. For example, prioritizing access to psychological support and intervention may be especially beneficial for those who score high on neuroticism and might be prone to experience increased emotional distress when exposed to new stressors. On the other hand, low conscientiousness scores may indicate a need for more administrative and/or team support to address potential challenges surrounding prioritizing tasks and assertiveness.

The current study findings should be considered in the context of potential limitations. Data were collected from a convenience sample from four units within a single children’s hospital and the majority of the sample was White, female, nurses, and worked in the ED. Collectively, the under- or over-representation of certain groups within the sample may limit the generalizability of current study findings to other medical settings. Although time 1 burnout among study completers did not differ from those lost to follow-up, attrition from time 1 to time 2 may have implications for external validity and selection bias. Other factors not assessed, including employment status or resignation, which has accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic52 may have also affected study attrition. We also did not collect pre-COVID-19 burnout levels nor assess safety concerns or family stressors, which may have affected burnout in our sample.

Conclusion

In a sample of pediatric HCWs, emotional exhaustion and depersonalization burnout significantly increased over 11-months of working during the COVID-19 pandemic, with the proportion of HCWs endorsing high emotional exhaustion or depersonalization burnout rising significantly. Study results demonstrated that certain demographic and psychological factors were associated with increased burnout, which may have implications for burnout mitigation strategies. Additional longitudinal research assessing HCW burnout during pandemic surges is needed to confirm the current results. Future research including more diverse HCW samples working in other units and within other institutions, as well as the assessment of additional social and institutional-level variables may help further characterize risk and protective factors associated with HCW burnout trajectory and inform the development and implementation of burnout interventions.

Data availability

The de-identified datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bodenheimer, T. & Sinsky, C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann. Fam. Med. 12, 573–576 (2014).

Jun, J., Ojemeni, M. M., Kalamani, R., Tong, J. & Crecelius, M. L. Relationship between nurse burnout, patient and organizational outcomes: Systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 119, 103933 (2021).

Kemper, K. J. et al. Burnout in pediatric residents: three years of national survey data. Pediatrics 145, e20191030 (2020).

Shanafelt, T. D. et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch. Intern. Med. 172, 1377–1385 (2012).

Buckley, L., Berta, W., Cleverley, K., Medeiros, C. & Widger, K. What is known about paediatric nurse burnout: a scoping review. Hum. Resour. Health 18, 9 (2020).

Gribben, J. L., MacLean, S. A., Pour, T., Waldman, E. D. & Weintraub, A. S. A cross-sectional analysis of compassion fatigue, burnout, and compassion satisfaction in pediatric emergency medicine physicians in the United States. Acad. Emerg. Med. 26, 732–743 (2019).

Patterson, J. & Gardner, A. Burnout rates in pediatric emergency medicine physicians. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 36, 192–195 (2020).

Starmer, A. J., Frintner, M. P. & Freed, G. L. Work-life balance, burnout, and satisfaction of early career pediatricians. Pediatrics 137, e20153183 (2016).

Maslach, C. A multidimensional theory of burnout. in Theories of organizational stress (ed. Cooper, C.) vol. 68 68–85 (Oxford University Press, 1998).

Dyrbye, L. N. et al. A cross-sectional study exploring the relationship between burnout, absenteeism, and job performance among American nurses. BMC Nurs. 18, 1–8 (2019).

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E. & Leiter, M. P. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual 191–205 (Consulting Psychologists Press Inc, 1996).

Montgomery, A. P., Patrician, P. A. & Azuero, A. Nurse Burnout Syndrome and Work Environment Impact Patient Safety Grade. J. Nurs. Care Qual. 37, 87–93 (2022).

Shanafelt, T. D., Dyrbye, L. N. & West, C. P. Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA 317, 901–902 (2017).

Wallace, J. E., Lemaire, J. B. & Ghali, W. A. Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet 374, 1714–1721 (2009).

West, C. P., Dyrbye, L. N. & Shanafelt, T. D. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J. Intern. Med. 283, 516–529 (2018).

Schooley, B., Hikmet, N., Tarcan, M. & Yorgancioglu, G. Comparing burnout across emergency physicians, nurses, technicians, and health information technicians working for the same organization. Med. (Baltim.) 95, e2856 (2016).

Chirico, F. et al. Prevalence, risk factors and prevention of burnout syndrome among healthcare workers: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J. Health Soc. Sci. 6, 465–491 (2021).

CHIRICO, F. et al. Workplace violence against healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J. Health Soc. Sci. 7, 14–35 (2022).

Fiest, K. M. et al. Experiences and management of physician psychological symptoms during infectious disease outbreaks: a rapid review. BMC Psychiatry 21, 91 (2021).

Morgantini, L. A. et al. Factors contributing to healthcare professional burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid turnaround global survey. PloS One 15, e0238217 (2020).

Amanullah, S. & Ramesh Shankar, R. The Impact of COVID-19 on Physician Burnout Globally: A Review. in vol. 8 421 (Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 2020).

Rodriguez, R. M. et al. Academic Emergency Medicine Physicians’ Anxiety Levels, Stressors, and Potential Stress Mitigation Measures During the Acceleration Phase of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acad. Emerg. Med. 27, 700–707 (2020).

Kelker, H. et al. Prospective study of emergency medicine provider wellness across ten academic and community hospitals during the initial surge of the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Emerg. Med. 21, 1–12 (2021).

Nguyen, J. et al. Impacts and challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency medicine physicians in the United States. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 48, 38–47 (2021).

Firew, T. et al. Protecting the front line: a cross-sectional survey analysis of the occupational factors contributing to healthcare workers’ infection and psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA. BMJ Open 10, e042752 (2020).

Maunder, R. G. et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital workers over time: Relationship to occupational role, living with children and elders, and modifiable factors. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 71, 88–94 (2021).

Brown, P. A., Slater, M. & Lofters, A. Personality and burnout among primary care physicians: an international study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 12, 169–177 (2019).

Kroencke, L., Geukes, K., Utesch, T., Kuper, N. & Back, M. Neuroticism and emotional risk during the Covid-19 Pandemic. (2020).

Heyming, T. W. et al. Predictors for COVID-19-related new-onset maladaptive behaviours in children presenting to a paediatric emergency department. J. Paediatr. Child Health https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.15579 (2021).

Heyming, T. W. et al. Rapid antibody testing for SARS-CoV-2 vaccine response in pediatric healthcare workers. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 113, 1–6 (2021).

John, O. P., Naumann, L. P. & Soto, C. J. Paradigm shift to the integrative Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. in Handbook of personality: Theory and research (eds. John, O. P., Robins, R. W. & Pervine, L. A.) 114–158 (Guilford Press, 2008).

Soto, C. J. & John, O. P. Short and extra-short forms of the Big Five Inventory–2: The BFI-2-S and BFI-2-XS. J. Res. Personal. 68, 69–81 (2017).

Schmitt, D. P., Allik, J., McCrae, R. R. & Benet-Martínez, V. The geographic distribution of Big Five personality traits: Patterns and profiles of human self-description across 56 nations. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 38, 173–212 (2007).

Spielberger, C. D. State-trait anxiety inventory for adults. (1983).

Kendall, P. C., Finch, A. J. Jr, Auerbach, S. M., Hooke, J. F. & Mikulka, P. J. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory: a systematic evaluation. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 44, 406 (1976).

LeBlanc, V. R. & Bandiera, G. W. The effects of examination stress on the performance of emergency medicine residents. Med. Educ. 41, 556–564 (2007).

Wong, M. L., Anderson, J., Knorr, T., Joseph, J. W. & Sanchez, L. D. Grit, anxiety, and stress in emergency physicians. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 36, 1036–1039 (2018).

González-Cabrera, J., Fernández-Prada, M., Iribar-Ibabe, C. & Peinado, J. M. Acute and chronic stress increase salivary cortisol: a study in the real-life setting of a national examination undertaken by medical graduates. Stress 17, 149–156 (2014).

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, P. L. & Lushene, R. E. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. (Consulting Psychologist Press, 1970).

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., Leiter, M. P., Schaufeli, W., & Schwab, R. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. 13–29 (Mind Garden, 2016).

Poghosyan, L., Aiken, L. H. & Sloane, D. M. Factor structure of the Maslach burnout inventory: an analysis of data from large scale cross-sectional surveys of nurses from eight countries. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 46, 894–902 (2009).

Hwang, C.-E., Scherer, R. F. & Ainina, M. F. Utilizing the Maslach Burnout Inventory in cross-cultural research. Int. J. Manag. 20, 3 (2003).

Greenglass, E. R., Burke, R. J. & Fiksenbaum, L. Workload and burnout in nurses. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 11, 211–215 (2001).

Maslach, C., Leiter, M. P. & Schaufeli, W. Measuring Burnout. in The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Well-being (eds. Cartwright, S. & Cooper, C. L.) (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Chirico, F., Nucera, G. & Leiter, M. Measuring burnout syndrome requires reliable and standardized measures. Hong. Kong J. Emerg. Med 29, 325–326 (2022).

Pantaleoni, J. L., Augustine, E. M., Sourkes, B. M. & Bachrach, L. K. Burnout in pediatric residents over a 2-year period: a longitudinal study. Acad. Pediatr. 14, 167–172 (2014).

Campbell, J., Prochazka, A. V., Yamashita, T. & Gopal, R. Predictors of Persistent Burnout in Internal Medicine Residents: A Prospective Cohort Study. Acad. Med. 85, 1630–1634 (2010).

Geuens, N., Van Bogaert, P. & Franck, E. Vulnerability to burnout within the nursing workforce-The role of personality and interpersonal behaviour. J. Clin. Nurs. 26, 4622–4633 (2017).

Giusti, E. M. et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on health professionals: a cross-sectional study. Front. Psychol. 11, 1684 (2020).

Staples, B. B. et al. Burnout and Association With Resident Performance as Assessed by Pediatric Milestones: An Exploratory Study. Acad. Pediatr. 21, 358–365 (2021).

West, C. P., Dyrbye, L. N., Erwin, P. J. & Shanafelt, T. D. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 388, 2272–2281 (2016).

Chirico, F. & Leiter, M. Tackling stress, burnout, suicide and preventing the “great resignation” phenomenon among healthcare workers (during and after the COVID-19 pandemic) for maintaining the sustainability of healthcare systems and reaching the 2030 sustainable development goals. J. Health Soc. Sci. 9–13 (2022).

Specht, J., Egloff, B. & Schmukle, S. C. Stability and change of personality across the life course: the impact of age and major life events on mean-level and rank-order stability of the big five. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 101, 862–882 (2011).

Borges, N. J. & Savickas, M. L. Personality and medical specialty choice: a literature review and integration. J of Career Assess.10, 362–380 (2002).

Spinhoven, P., Huijbers, M. J., Ormel, J. & Speckens, A. E. Improvement of mindfulness skills during mindfulness-based cognitive therapy predicts long-term reductions of neuroticism in persons with recurrent depression in remission. J. Affect. Disord. 213, 112–117 (2017).

Funding

S.R.M. is supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute for Child Health and Human Development (K23HD105042, PI: Martin).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each author has met the Pediatric Research authorship requirements. The authors that met each criterion are listed below. - Substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data: S.R.M., Z.N.K., T.H., M.A.F., L.S., T.S., and T.M.. -Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content: S.R.M., Z.N.K., T.H., M.A.F., L.S., T.S., and T.M. -Final approval of the version to be published: S.R.M., T.H., M.A.F., L.S., T.S., Z.N.K., and T.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Z.N.K. serves as a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences and Pacira and is the President of the American College of Perioperative Medicine. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Consent statement

Healthcare worker participants completed informed consent prior to completing study procedures.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Martin, S.R., Heyming, T., Morphew, T. et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric healthcare burnout in acute care: a longitudinal study. Pediatr Res 94, 1771–1778 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-023-02674-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-023-02674-3

- Springer Nature America, Inc.

This article is cited by

-

“The forest and the trees”: a narrative medicine curriculum by residents for residents

Pediatric Research (2024)