Abstract

BACKGROUND

Few studies have characterized follow-up after pediatric acute kidney injury (AKI). Our aim was to describe outpatient AKI follow-up after pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) admission.

METHODS

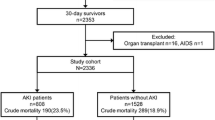

Two-center retrospective cohort study (0–18 years; PICU survivors (2003–2005); noncardiac surgery; and no baseline kidney disease). Provincial administrative databases were used to determine outcomes. Exposure: AKI (KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) definitions). Outcomes: post-discharge nephrology, family physician, pediatrician, and non-nephrology specialist visits. Regression was used to evaluate factors associated with the presence of nephrology follow-up (Cox) and the number of nephrology and family physician or pediatrician visits (Poisson), among AKI survivors.

RESULTS

Of n = 2041, 355 (17%) had any AKI; 64/355 (18%) had nephrology; 198 (56%) had family physician or pediatrician; and 338 (95%) had family physician, pediatrician, or non-nephrology specialist follow-up by 1 year post discharge. Only 44/142 (31%) stage 2–3 AKI patients had nephrology follow-up by 1 year. Inpatient nephrology consult (adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) 7.76 [95% confidence interval (CI) 4.89–12.30]), kidney admission diagnosis (aHR 4.26 [2.21–8.18]), and AKI non-recovery by discharge (aHR 2.65 [1.55–4.55]) were associated with 1-year nephrology follow-up among any AKI survivors.

CONCLUSIONS

Nephrology follow-up after AKI was uncommon, but nearly all AKI survivors had follow-up with non-nephrologist physicians. This suggests that AKI follow-up knowledge translation strategies for non-nephrology providers should be a priority.

Impact

-

Pediatric AKI survivors have high long-term rates of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and hypertension, justifying regular kidney health surveillance after AKI.

-

However, there is limited pediatric data on follow-up after AKI, including the factors associated with nephrology referral and extent of non-nephrology follow-up.

-

We found that only one-fifth of all AKI survivors and one-third of severe AKI (stage 2–3) survivors have nephrology follow-up within 1 year post discharge.

-

However, 95% are seen by a family physician, pediatrician, or non-nephrology specialist within 1 year post discharge.

-

This suggests that knowledge translation strategies for AKI follow-up should be targeted at non-nephrology healthcare providers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute kidney injury (AKI) occurs in at least 15% of children admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).1,2,3 Pediatric AKI is associated with increased mortality, morbidity measures, and healthcare costs.2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 Pediatric AKI survivors are at long-term risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and hypertension.8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21 This recent evidence suggests that there is a need to follow-up children after AKI hospitalizations to detect kidney health issues, prevent AKI recurrence, and manage CKD or hypertension.22,23 The international Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) 2012 AKI guidelines provide a non-graded recommendation to “evaluate patients 3 months after AKI for resolution, new onset, or worsening of pre-existing CKD,” based largely on adult data.24

Recent studies show that nephrology follow-up after AKI is uncommon, including among children who have evidence of CKD by 3–5 years after discharge.11,12 In a large cohort of PICU patients, we found that PICU-AKI was associated with higher risks of 30-day, 1-year, and 5-year outpatient physician visits (adjusted relative risk (RR) 1.15–1.26), regardless of whether nephrology visits were considered.25 In adults, nephrology follow-up after AKI has been associated with lower 2-year mortality.26,27 Since these data were published, post-AKI follow-up clinics in adults have been initiated and evaluated.26,28 For example, FUSION is an ongoing randomized controlled trial of an AKI follow-up clinic vs. usual care for adult AKI survivors to determine the risks of 1-year mortality and CKD (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02483039). In children, there is limited data on follow-up after hospitalizations with an AKI, including factors associated with nephrology referral, which healthcare providers (e.g., specialists, family physicians (FPs), pediatricians (Peds)) are providing follow-up and the extent of this follow-up. This information would inform on realistic opportunities to target knowledge translation regarding post-AKI surveillance towards specific physician groups with more frequent post-AKI patient contact. Such data would also inform on how to approach pediatric process of care algorithms and interventions for AKI follow-up.

In a two-center, retrospective longitudinal cohort study of critically ill children followed for 5 years after hospital discharge, we determined the frequency of and factors associated with outpatient nephrologist (Neph), FP, general Ped, and non-nephrology subspecialist (Spec) visits after an episode of AKI. We hypothesized that few AKI survivors would have nephrology follow-up, but that nearly all children would have other physician visits within 1 year after hospital discharge.

Methods

Design, setting, and patient selection

This study was a secondary analysis of a previously reported retrospective cohort study of children (0–18 years) admitted to two PICUs in Montreal, Canada (Montreal Children’s Hospital; Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Sainte-Justine) between January 2003 and March 2005.8,21,25,29,30 The exclusion criteria were: pre-existing kidney failure or CKD (by chart review); post-cardiac surgery; hospital non-survivors; and invalid provincial health insurance number. We included only the first eligible hospitalization during the study period. Approvals from institutional research ethics boards and the Commission d’accès à l’information du Québec (provincial data monitoring board) were obtained and the need for informed consent was waived.

Data collection and sources

PICU and hospitalization data were collected retrospectively, as previously described.8,25,31 Briefly, patient and PICU data collected by individual chart review included demographics; patient registration with a FP or Ped prior to admission; diagnoses; treatments; laboratory results (including daily serum creatinine (SCr)); and urine output (UO) (8-h intervals). We classified children by PICU admission diagnosis; children admitted to the PICU for a new kidney diagnosis (excluding pre-existing kidney disease or kidney failure) were classified as “kidney admission diagnosis.” These data were merged with Quebec Vital Statistics Registry and Quebec administrative healthcare databases (Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec and Med-Echo) up to March 2010. These databases include (1) demographic information, (2) medical services data (including outpatient services date, type, billing codes, diagnostic codes; inpatient admission and discharge dates; admission; and other diagnostic procedures); and (3) outpatient prescription data (for ~50% patients with provincial medication coverage). These databases were used to determine the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm (PMCA) classification.25,32 PMCA is a validated algorithm that uses healthcare administrative coding to classify children by medical complexity (no chronic disease, noncomplex chronic disease, and complex chronic disease).

Primary exposure: AKI during PICU admission

From retrospective chart data, AKI was defined and staged (stages 1–3) based on the KDIGO SCr and UO criteria. The term “any AKI” was used to describe children with AKI of any stage (stages 1–3). Baseline SCr was the lowest measurement within 3 months pre-admission. If unavailable, baseline SCr was estimated using a previously validated method, assuming a normal estimated glomerular filtration rate.8,21,29,31 AKI during PICU was classified as the worst AKI stage (by SCr or UO criteria). As previously described, children without sufficient SCr or UO data to ascertain AKI were classified as non-AKI.21 We used the last SCr measurement during index hospitalization to define lack of AKI recovery by discharge (last SCr >1.5 times baseline).

Outcomes: nephrology, Ped, FP, and non-nephrology Spec outpatient visits

We evaluated the number of Neph, FP, Ped, and Spec visits (events) by 90 days, 1 year, and 5 years post index hospitalization. Day 0 was the hospital discharge date. Outcomes were expressed as:

-

(a)

proportion of patients with ≥1 event (e.g., ≥1 Neph visit; ≥1 FP or Ped visit) during the given follow-up period (90 days, 1 year, and 5 years),

-

(b)

number of events by 1 year and 5 years after hospital discharge,

-

(c)

rate (events per person-year) of events by 1 year and 5 years after hospital discharge.

Analysis

Baseline characteristics by AKI stage were compared using distribution-appropriate univariate tests. The proportion of children with ≥1 event, number of events, and event rate were calculated for each outcome by time period. We compared the proportion of children with ≥1 event, between those with vs. without any AKI, and with vs. without stage 2–3 AKI using χ2 tests. We chose to combine individuals with no AKI and stage 1 AKI, together for comparison against children with stage 2–3 AKI, due to differences in subsequent CKD risk between these cohorts and for consistency with currently published recommendations, which prioritize nephrology follow-up for severe AKI survivors.22,23,28 We used the Kaplan–Meier method to evaluate time-to-Neph, FP or Ped, and FP, Ped, or Spec visits, comparing AKI groups using the log-rank test.

We evaluated factors associated with ≥1 Neph visit and ≥1 FP or Ped visits (binary variables) by 1 year and by 5 years after hospital discharge using appropriate univariable tests. For the binary Neph visits outcome, we performed Cox regression analysis to determine unadjusted hazard ratios (HR) for association of variables with this outcome. Variables significantly associated (p < 0.01) with ≥1 Neph visits by 1 year and 5 years were included in 1- and 5-year multivariable Cox models, respectively. We decided a priori to include FP or Ped registration in the multivariable models and exclude kidney replacement therapy receipt (due to low event numbers) and hospital length of stay. The Cox models were tested for the proportionality assumption and death was treated as a censoring event.

We performed univariable Poisson regression to determine factors associated with the number of Neph, and FP or Ped visits per person-time (count variables) by 1 year and 5 years, by calculating the unadjusted RRs. Rates of follow-up were measured as events per person-time in Poisson regressions to account for variable patient follow-up duration. Using the same variables as above for the ≥1 Neph visit 1- and 5-year models, we performed multivariable Poisson regression to estimate adjusted RR for FP or Ped visits. Finally, children with any AKI defined by the SCr criteria were compared against those defined by the UO criteria for the proportion with ≥1 Neph visit by 90 days, 1 year, and 5 years. Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS statistical software version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of 2041 eligible PICU survivors (56% male, mean age at admission 6.5 ± 5.8 years), any AKI occurred in 355 children (17.4%; n = 213 stage 1, n = 142 stages 2 and 3). Children with stage 2–3 AKI had higher illness severity measures than children with no AKI, including higher Pediatric Risk of Mortality scores (median score 13 vs. 6); longer PICU stay (median 3 days vs. 1 day) and hospital stay (median 17 vs. 7 days); more mechanical ventilation (49 vs. 34%); and more vasopressor use (26 vs. 5%) (Supplementary Table 1). Children with any AKI also had more PMCA complex chronic disease (74% AKI stages 2– and vs. 68% AKI stage 1 vs. 55% no AKI) and more inpatient nephrology consultations (37% AKI stages 2 and 3 vs. 13% AKI stage 1 vs. 3% no AKI). Among those with any AKI, the last measured SCr during hospitalization demonstrated a lack of AKI recovery in 44 children (12.4%).

Nephrology follow-up

Among 355 any AKI survivors, 50 (14%), 64 (18%), and 83 (23%) had ≥1 outpatient Neph visit by 90 days, 1 year and 5 years post discharge (Table 1). Stage 2–3 AKI survivors were significantly more likely to have ≥1 Neph visit vs. children with no AKI or stage 1 AKI during the same time periods (e.g., by 1 year 44/142 (31%) of stage 2–3 AKI survivors vs. 138/1899 (7%) of no AKI or stage 1 AKI survivors) and saw nephrologists sooner post discharge (Fig. 1a). Among any AKI survivors who were not seen by nephrologists, 2/305 (0.7%) died before 90 days, 10/291 (2.8%) before 1 year, and 19/272 (7.0%) before 5 years. Among 12 children with AKI requiring dialysis, 9 (75%) had Neph follow-up by 1 year. Any AKI survivors with lack of AKI recovery (vs. recovery) by hospital discharge were more likely to have nephrology follow-up by 1 year (25/49 (51%) vs. 32/147 (22%), respectively, p < 0.001). Any AKI survivors had a higher rate (visits per time) of Neph visits between 0–1 and 1–5 years post discharge vs. children without AKI (Supplementary Table 2). Among 83 any AKI survivors with outpatient nephrology follow-up, the median time to first visit was 35 days (interquartile range (IQR) 7–335 days) post discharge and median follow-up duration was 9 months (IQR 0–47 months). Comparing children with any AKI defined by the SCr criteria vs. by the UO criteria, there were no statistically significant differences between groups in the proportion of children with Neph follow-up by 90 days, 1 year, and 5 years (Supplementary Table 3).

a Time-to-event analysis for outpatient nephrology follow-up among PICU survivors by AKI status. Outpatient nephrology follow-up was significantly more common among stage 2–3 AKI survivors than children with stage 1 or no AKI (p < 0.0001, log-rank test). Stage 2–3 AKI survivors had outpatient nephrology visits sooner after discharge, compared with stage 1 or no AKI children. b Time-to-event analysis for outpatient family physician (FP) or general pediatrician (Ped) follow-up among PICU survivors by AKI status. There was no significant difference in the timing of outpatient FP or Ped follow-up between stage 2–3 AKI survivors and children with stage 1 or no AKI (p = 0.06, log-rank test). c Time-to-event analysis for outpatient family physician FP, general pediatrician (Ped), or non-nephrology subspecialist (Spec) follow-up among PICU survivors by AKI status. Stage 2–3 AKI survivors were more likely to have outpatient FP, Ped, or Spec follow-up sooner, compared against children with stage 1 or no AKI (p = 0.0004, log-rank test). However, >90% of each group had outpatient FP, Ped, or Spec follow-up by 1 year post discharge.

Variables significantly associated with ≥1 Neph visit by 1 year post discharge (Table 2) were inpatient Neph consult (adjusted HR 7.76 [95% CI 4.89–12.30]), kidney admission diagnosis (aHR 4.26 [2.21–8.18]), and lack of AKI recovery by discharge (aHR 2.65 [1.55–4.55]). Variables associated with ≥1 Neph visit by 5 years were similar (inpatient Neph consult, aHR 6.59 [4.39–9.89]; kidney admission diagnosis, aHR 4.78 [2.50–9.12]; lack of AKI recovery by discharge, aHR 2.26 [1.37–3.73]), in addition to the presence of oncologic admission diagnosis (aHR 2.09 [1.16–3.78]), gastrointestinal admission diagnosis (aHR 1.82 [1.10–3.01]), and AKI stages 2 and 3 (aHR 1.33 [1.06–1.67]). Admission to Sainte-Justine Hospital was negatively associated with Neph follow-up by 1 year (aHR 0.35 [0.23–0.51]) and 5 years (aHR 0.34 [0.24–0.47]). Factors associated with the number of Neph visits by multivariable Poisson regression were similar to those associated with the binary Neph visit outcome (Supplementary Table 4).

FP, general Ped, and non-Nephrology Spec Follow-up

Among 355 any AKI survivors, 113 (32%), 198 (56%), and 297 (84%) had ≥1 FP or Ped visit by 90 days, 1 year, and 5 years post discharge (Fig. 1b and Table 1). When including Spec visits (thus ≥1 FP, Ped, or Spec visit), 311 any AKI survivors (88%) had ≥1 outpatient physician visit within 90 days, 338 (95%) by 1 year, and 349 (98%) by 5 years (Fig. 1c and Table 1). Median time to first FP, Ped, or Spec visit from hospital discharge date was 12 days (IQR 6–30 days). Stage 2–3 AKI survivors were more likely to have a FP, Ped, or Spec visit by 90 days vs. those with no AKI or stage 1 AKI (130/142 (92%) vs. 1610/1899 (85%), respectively, p = 0.03). There was no statistically significant difference between AKI groups at 1 year or 5 years (Table 1). Ten of 12 children (83%) with dialysis-receiving AKI had 1-year FP or Ped follow-up. Any AKI survivors with lack of AKI recovery by discharge (vs. recovered from AKI) were more likely to have 1-year FP or Ped follow-up (39/49 (80%) vs. 97/179 (54%), respectively, p = 0.001). Between 0 and 1 year post discharge, any AKI survivors had higher rates (events per person-year (py)) of Ped (3.9 vs. 3.3 events/py) and Spec visits (8.8 vs. 5.4 events/py) compared to children with no AKI, but lower rates of FP visits (1.3 vs. 1.7 events/py, Supplementary Table 2).

Factors that were significantly associated with a number of FP or Ped visits by 1 year post discharge (Table 3) were oncologic admission diagnosis (RR 5.96 [4.76–7.45]), kidney admission diagnosis (RR 2.78 [2.28–3.39]), inpatient Neph consult (RR 1.75 [1.60–1.92]), AKI stage 2–3 (RR 1.38 [1.26–1.51]), Hospital Sainte-Justine (RR 1.29 [1.19–1.41]), and FP or Ped registration (RR 1.13 [1.06–1.22]). Factors associated with the number of FP or Ped visits by 5 years were also similar (oncologic admission diagnosis, RR 7.37 [6.16–8.81]; kidney admission diagnosis, RR 5.68 [4.90–6.58]; inpatient Neph consult, RR 1.53 [1.43–1.63]; Sainte-Justine Hospital, RR 1.43 [1.34–1.52]; and FP or Ped registration, RR 1.07 [1.02–1.12]), in addition to neurologic/neurosurgical admission diagnosis (RR 1.40 [1.10–1.77]). In contrast, AKI stage 2–3 was not significantly associated with 5-year FP or Ped visits (RR 1.04 [0.99–1.11]). Lack of AKI recovery (RR 0.79 [0.75–0.84]), gastrointestinal admission diagnosis (RR 0.82 [0.67–0.99]), and PMCA noncomplex (RR 0.63 [0.51–0.78]) or complex chronic disease (RR 0.50 [0.42–0.60]) were negatively associated with the number of 5-year FP or Ped visits.

Discussion

Our study characterizes outpatient follow-up patterns after AKI among a cohort of PICU survivors. Overall, only 18% of any AKI survivors and 31% of stage 2–3 AKI survivors had Neph follow-up within 1 year post discharge. Just over half of any AKI survivors saw a FP or Ped within 1 year and 95% of children were seen by a FP, Ped, or Spec. Therefore, an opportunity exists to promote enhanced post-AKI follow-up care with effective knowledge translation strategies targeting non-Neph physicians. Post-AKI follow-up typically involves screening for CKD and associated complications (by measurement of kidney function, blood pressure, and proteinuria), medication review, patient, and family education about AKI and CKD risk and discussion of nephrotoxin avoidance/mitigation strategies. A quality improvement framework for post-AKI follow-up has recently been described in recommendations from the Acute Disease Quality Initiative.22 Enhanced post-AKI follow-up could result in earlier detection of CKD and implementation of interventions to delay CKD progression, it could help identify blood pressure abnormalities and reduce the risk of long-term cardiovascular events, and it could help prevent recurrent AKI. In adults, there is preliminary data that post-AKI follow-up clinic visits may be associated with decreased mortality after AKI.26 Elucidating the actual process of healthcare after an episode of AKI in children will increase the likelihood of making appropriate changes and developing realistic future follow-up interventions.

Our results are consistent with other adult and pediatric studies, reporting low frequencies of nephrology follow-up post AKI. Among 57 cardiac surgery-associated AKI survivors in the TRIBE-AKI study, only two had outpatient nephrology follow-up.12 Askenazi et al.11 described 17 pediatric AKI survivors with evidence of kidney injury at 3–5 year follow-up, and found that about one-third had nephrology follow-up. Excluding oncology populations, prospective pediatric AKI studies also have high losses to follow-up (29–68%).23 USRDS 2018 (United States Renal Data System 2018) data found that 17% of all adult AKI survivors and 9% of those without pre-existing CKD or diabetes had nephrology follow-up within 6 months post discharge, and the frequency of nephrology follow-up decreased between 2006 and 2016.33 A recent study by Karsanji et al.34 compared recommended follow-up using clinical vignettes vs. actual documented follow-up for stage 3 AKI survivors in Alberta, Canada. Although nephrologists stated that they would follow-up 87% of cases, only 24% of stage 3 AKI survivors had nephrology follow-up within 1 year. This disparity highlights that knowledge, resource, system, or patient barriers may prevent more frequent nephrology follow-up after severe AKI. Karsanji et al. also observed that 99% of adult AKI survivors had ≥1 non-nephrology physician visit within 1 year. This emphasizes the opportunity to enhance post-AKI surveillance delivered by non-Neph physicians.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to evaluate factors associated with outpatient nephrology follow-up after pediatric AKI. We found that inpatient nephrology consultation, kidney admission diagnosis, and lack of AKI recovery were the most strongly associated factors with nephrology follow-up by 1 year and 5 years post discharge. This suggests that awareness of the need for post-AKI surveillance exists for these high-risk populations. Children with oncologic or gastrointestinal admission diagnoses were also more likely to have nephrology follow-up by 5 years post discharge, suggesting that there may be awareness of the CKD risk in these specific populations. We found that the proportion of children with ≥1 nephrology and FP or Ped visit was lower among children admitted to Sainte-Justine hospital, but that they had a greater number of both visits. This demonstrates that significant practice variation may exist between institutions; many possible factors may contribute to this practice variation, including patient factors, institutional factors, and geographic location of patients. This finding highlights the potential benefit of individual institutions to understand and potentially monitor what kind of follow-up patients receive after hospital discharge, with a goal to determine if any changes in institutional practice may be required. We also observed that children with AKI non-recovery were more likely to have had a nephrology visit and had fewer FP or Ped visits by 5 years post discharge; this may suggest that the presence of Neph follow-up (or other specialists) may have significant interactions with patterns of primary care physician follow-up. Future research aimed at understanding what factors drive use of primary care after a hospitalization may elucidate this finding. Enhanced post-AKI care could promote earlier recognition of CKD, hypertension, and associated complications. This would provide opportunities for treatment, risk factor modification, and patient education, with the objective to delay CKD progression and prevent AKI recurrence.

We are unaware of pediatric studies evaluating specific interventions for AKI survivors. The concept of post-AKI follow-up clinics has gained popularity in recent years, supported by a 2-year mortality benefit in adults (HR 0.76 [95% CI: 0.62–0.93]).26 There is ongoing adult research surrounding the outcomes associated with post-AKI follow-up clinics (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02483039), and one dedicated pediatric follow-up clinic has been described in the literature.28 However, there is no data yet on the impact of this pediatric post-AKI follow-up clinic, and the extent to which their methods apply to other healthcare contexts is unknown. In a systematic review by Greenberg et al.,9 the cumulative incidence of CKD stages 1 and 2 and CKD stage 3 or worse after pediatric AKI was 6.3 and 0.8 per 100 patient-years, respectively. Therefore, widespread implementation of post-AKI follow-up clinics would require significant healthcare resources to detect few cases of CKD. A more cost-effective approach would be to integrate post-AKI surveillance with routine physician visits. We found that 95% of pediatric AKI survivors had physician follow-up within 1 year, which may be more common in a universal healthcare system such as Canada, with fewer financial barriers to accessing follow-up care. This may be particularly relevant for post-AKI follow-up, which could be seen as unnecessary by families following their child’s recovery from an acute illness. While overall rates of physician follow-up were high, rates of FP or Ped follow-up were lower than expected (~56% by 1 year post discharge), which may have reflected a perception among families and healthcare providers that additional primary care follow-up was not needed in the presence of ongoing pediatric subspecialty follow-up. However, the exact rationale for decisions regarding post-AKI follow-up is unknown and likely multifactorial. Fortunately, the accessibility of blood pressure, SCr, and proteinuria measurement enables non-nephrology healthcare providers to implement post-AKI surveillance. The nephrology community can contribute by creating pragmatic pediatric AKI follow-up guidelines and increasing awareness of the CKD risk associated with AKI to non-nephrologists.22 AKI survivors who are at elevated CKD risk may benefit from early nephrology referral post discharge. Until future research establishes specific high-risk groups or a predictive model for CKD risk post AKI, a reasonable approach may be to refer all children with severe AKI (stages 2 and 3), dialysis-receiving AKI, lack of AKI recovery, recurrent AKI, or pre-existing kidney disease to nephrology.28,35 Improved AKI identification during hospitalization using electronic warning tools, clear communication with families, and documentation of AKI occurrence (and follow-up recommendations) in discharge summaries may help improve post-AKI care.22

This study has a number of limitations. The retrospective nature of our study prevented us from capturing pre-existing co-morbidities that were not documented in admission records. If a child was re-hospitalized post-discharge, this may have resulted in missed or postponed outpatient visits, consistent with real-world follow-up. We did not have SCr measurements in a significant proportion of children eligible for analysis (23%); these children were classified as “no AKI” by SCr criteria based on their low theoretical AKI risk, as our previous work has suggested is valid.21,36 Children classified as “no AKI” were combined with stage 1 AKI for the purpose of comparison against children with severe AKI (stage 2–3). We did this to evaluate the effect of AKI severity on nephrology follow-up after discharge and to compare against previous studies reporting healthcare utilization of children with stage 2–3 AKI together.12,25 In clinical practice, we observe that children with fully recovered stage 1 AKI typically do not receive additional CKD surveillance post discharge, making it appropriate to analyze them together with children that did not experience AKI. However, we acknowledge that classifying stage 1 AKI and no AKI survivors together may reduce differences between them and severe AKI survivors, biasing towards the null hypothesis for these analyses. The majority of patients had baseline SCr back-calculated due to lack of baseline SCr, which is an issue with all retrospective pediatric AKI studies.2

We were not able to reliably evaluate potentially confounding variables following hospital discharge, such as recurrent AKI or CKD development. We used healthcare administrative databases to capture outpatient physician visit data, which carries a risk of miscoding for physician type or service date. However, accurate coding is a requirement for physician billing and is therefore likely to be reliably captured. Our study was performed at two tertiary pediatric centers in Quebec, Canada (a universal healthcare system). Therefore, healthcare utilization and referral patterns may not be generalizable to other populations, particularly countries without universal healthcare. Finally, one important limitation is that our last patient follow-up captured was ~10 years ago and additional data collection was not feasible due to limited funding for this secondary analysis. We acknowledge that outpatient physician follow-up patterns may have changed over the past decade. It is possible that greater physician awareness of the adverse outcomes associated with AKI may have increased rates of SCr monitoring and nephrology referrals. However, the lack of pediatric-specific AKI follow-up guidelines or novel post-AKI interventions since then suggests that follow-up patterns may remain similar. This theory is supported by adult USRDS data, which has found that the proportion of AKI survivors who visit a Neph within 6 months of hospital discharge has actually decreased over the past decade.33

Conclusion

Less than one in five children with PICU-AKI have outpatient nephrology follow-up within 1 year of discharge. However, nearly all AKI survivors had follow-up within 1 year with a non-Neph physician, providing opportunities for enhanced post-AKI surveillance at other healthcare visits. Knowledge translation strategies regarding post-AKI follow-up should therefore be targeted at non-Neph physicians.

References

Wang, L. et al. Electronic health record-based predictive models for acute kidney injury screening in pediatric inpatients. Pediatr. Res. 82, 465–473 (2017).

Kaddourah, A. et al. Epidemiology of acute kidney injury in critically ill children and young adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 376, 11–20 (2017).

Kari, J. A. et al. Outcome of pediatric acute kidney injury: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Pediatr. Nephrol. 33, 335–340 (2018).

Sutherland, S. M. et al. AKI in hospitalized children: epidemiology and clinical associations in a national cohort. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 8, 1661–1669 (2013).

Susantitaphong, P. et al. World incidence of AKI: a meta-analysis. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 8, 1482–1493 (2013).

Sutherland, S. M. et al. AKI in hospitalized children: comparing the pRIFLE, AKIN, and KDIGO definitions. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10, 554–561 (2015).

Alkandari, O. et al. Acute kidney injury is an independent risk factor for pediatric intensive care unit mortality, longer length of stay and prolonged mechanical ventilation in critically ill children: a two-center retrospective cohort study. Crit. Care 15, R146 (2011).

Hessey, E. et al. Long-term mortality after acute kidney injury in the pediatric ICU. Hosp. Pediatr. 8, 260–268 (2018).

Greenberg, J. H., Coca, S. & Parikh, C. R. Long-term risk of chronic kidney disease and mortality in children after acute kidney injury: a systematic review. BMC Nephrol. 15, 184 (2014).

Hui-Stickle, S., Brewer, E. D. & Goldstein, S. L. Pediatric ARF epidemiology at a tertiary care center from 1999 to 2001. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 45, 96–101 (2005).

Askenazi, D. J. et al. 3-5 year longitudinal follow-up of pediatric patients after acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 69, 184–189 (2006).

Greenberg, J. H. et al. Kidney outcomes 5 years after pediatric cardiac surgery: the TRIBE-AKI study. JAMA Pediatr. 170, 1071–1078 (2016).

Mammen, C. et al. Long-term risk of CKD in children surviving episodes of acute kidney injury in the intensive care unit: a prospective cohort study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 59, 523–530 (2012).

Menon, S., Kirkendall, E. S., Nguyen, H. & Goldstein, S. L. Acute kidney injury associated with high nephrotoxic medication exposure leads to chronic kidney disease after 6 months. J. Pediatr. 165, 522–527.e2 (2014).

Hollander, S. A. et al. Recovery from acute kidney injury and CKD following heart transplantation in children, adolescents, and young adults: a retrospective cohort study. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 68, 212–218 (2016).

Madsen, N. L. et al. Cardiac surgery in patients with congenital heart disease is associated with acute kidney injury and the risk of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 92, 751–756 (2017).

Garg, A. X. et al. Long-term renal prognosis of diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. JAMA 290, 1360–1370 (2003).

Cooper, D. S. et al. Follow-up renal assessment of injury long-term after acute kidney injury (FRAIL-AKI). Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 11, 21–29 (2016).

Hirano, D. et al. Independent risk factors and 2-year outcomes of acute kidney injury after surgery for congenital heart disease. Am. J. Nephrol. 46, 204–209 (2017).

Hoffmeister, P. A. et al. Hypertension in long-term survivors of pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 16, 515–524 (2010).

Hessey, E. et al. Acute kidney injury in critically ill children and subsequent chronic kidney disease. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 6, 2054358119880188 (2019).

Kashani, K. et al. Quality improvement goals for acute kidney injury. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14, 941–953 (2019).

Goldstein, S. L. et al. AKI transition of care: a potential opportunity to detect and prevent CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 8, 476–483 (2013).

Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Acute Kidney Injury Work Group. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Kidney Injury. Section 2: AKI definition. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2, 19–36 (2012).

Hessey, E. et al. Healthcare utilization after acute kidney injury in the pediatric intensive care unit. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 13, 685–692 (2018).

Harel, Z. et al. Nephrologist follow-up improves all-cause mortality of severe acute kidney injury survivors. Kidney Int. 83, 901–908 (2013).

Khan, I. H., Catto, G. R., Edward, N. & Macleod, A. M. Acute renal failure: factors influencing nephrology referral and outcome. QJM 90, 781–785 (1997).

Silver, S. A. et al. Ambulatory care after acute kidney injury: an opportunity to improve patient outcomes. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2, 71 (2015) .

Hessey, E. et al. Renal function follow-up and renal recovery after acute kidney injury in critically ill children. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 18, 733–740 (2017).

D’Arienzo, D. et al. A validation study of administrative health care data to detect acute kidney injury in the pediatric intensive care unit. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 6, 205435811982752 (2019).

Hessey, E. et al. Evaluation of height-dependent and height-independent methods of estimating baseline serum creatinine in critically ill children. Pediatr. Nephrol. 32, 1953–1962 (2017).

Simon, T. D. et al. Pediatric medical complexity algorithm: a new method to stratify children by medical complexity. Pediatrics 133, e1647–e1654 (2014).

United States Renal Data System. USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States (National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2018).

Karsanji, D. J. et al. Disparity between nephrologists’ opinions and contemporary practices for community follow-up after AKI hospitalization. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 12, 1753–1761 (2017).

Sigurjonsdottir, V. K., Chaturvedi, S., Mammen, C. & Sutherland, S. M. Pediatric acute kidney injury and the subsequent risk for chronic kidney disease: is there cause for alarm? Pediatr. Nephrol. 33, 2047–2055 (2018).

Benisty, K. et al. Kidney and blood pressure abnormalities 6 years after acute kidney injury in critically ill children: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr. Res. 88, 271–278 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by an operating grant from the Fonds de Recherche du Quebec-Sante. M.Z. was supported by a research salary award from the Fonds de Recherche du Quebec-Sante during the performance of the majority of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.R., R.C. and M.Z. conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection and/or analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. J.L., P.J. and V.P. conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection and analysis, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. E.H. and S.N. conceptualized and designed the study, performed data collection, reviewed data analyses, assisted with data interpretation, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. M.D. reviewed and revised the proposed study design, was primarily responsible for data analysis, and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors have approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data sharing

Deidentified individual participant data will not be made available.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Robinson, C., Hessey, E., Nunes, S. et al. Acute kidney injury in the pediatric intensive care unit: outpatient follow-up. Pediatr Res 91, 209–217 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01414-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01414-9

- Springer Nature America, Inc.

This article is cited by

-

Improving Acute Kidney Injury-Associated Outcomes: From Early Risk to Long-Term Considerations

Current Treatment Options in Pediatrics (2021)