Abstract

Background

Mental health (MH) conditions are highly prevalent, yet only marginal portions of children receive adequate services. Access to specialized mental healthcare is limited and, consequently, pediatricians remain the source of management and care of children with MH disorders. Despite this, research suggests that pediatricians report lack of access to training and support regarding MH care of youth, leading to discomfort with managing the population they are asked to treat. An additional barrier to care that has less research is perceptions regarding MH disorders among pediatricians. This scoping review aims to describe the state of science regarding perceptions and possible stigma towards MH in pediatric primary care.

Methods

PsychInfo, PubMed Medline, Ovid Medline, CINAHL, and Embase were searched with terms related to stigma, pediatricians, and MH disorders. New research articles were included after review, which addressed stigma in pediatricians treating youth with MH disorders.

Results

Our initial search produced 457 titles, with 23 selected for full-text review, and 8 meeting inclusion criteria, N = 1571 pediatricians.

Conclusions

While a limited number of studies focus on physician-based perceptions/stigma, and even less data on pediatrician stigma towards MH, more studies are needed to explore how this impacts patient care.

Impact

-

In this scoping review, we sought to shed light on the limitations regarding MH care access, especially with the increasing need for care and not enough MH specialists, adding to an already tremendous burden pediatric primary care providers face daily.

-

We also reviewed barriers to said care within pediatric primary care, including the potential for physician stigma towards MH diagnosis, treatment, and management.

-

This review adds a concise summary of the current limited studies on stigma towards MH within primary care pediatricians and the importance of continued research into how perception and stigma affect patient care.

-

This material is an original project and has not been previously published.

-

This work is not submitted for publication or consideration elsewhere

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

In the United States, one in five youth has a mental health disorder, such as anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).1,2,3 These conditions impair an affected child’s relationships within school, family, and with peers.1,4 Mental health disorders in childhood are associated with significant morbidity, including chronic physical and mental health problems, such as the increased risk for obesity, heart disease, or suicide attempts.5

Although common and associated with significant morbidity, there are evidence-based and effective treatments for child and adolescent mental health disorders. However, only 25–35% of those needing treatment are able to access care in a subspecialty setting.3,6 Child psychiatrists, specialists in treating mental health disorders in the pediatric population, represent an area of critical healthcare shortage. In 2019, there were ~2000 children with serious mental health disorders for every one child psychiatrist in the country.7 With 42 of the 50 states defined as “severe shortage” areas for child psychiatry, the remaining eight are defined as “high shortage” areas.7 Although child psychiatrists are the specialists in this arena, general pediatricians are licensed to treat serious mental health disorders in their young patients.8 However, this training is variable based on the training site and training years.2,9,10 Primary care pediatricians are subsequently located at an important intersection in medicine, with the ability and contact level for early diagnosis and intervention in behavioral health.1,11,12

While general pediatricians are the first contact for many youths with mental health concerns, limited research suggests that general pediatricians report difficulty integrating screening tools and mental health guidance into an already limited amount of patient contact time.5,6,13,14,15 Adding more complexity, pediatricians already balance anticipatory guidance, developmental screening, and time-consuming administrative tasks.15 There are limits in resource options to refer out for mental health subspecialty collaboration as well.16 Primary care pediatricians also reported concerns regarding the lack of preparation in training to effectively diagnose and treat childhood mental health disorders.17 Diamond et al.18 found that pediatricians who reported sufficient knowledge regarding adolescent suicide risk assessment were up to five times more likely to screen for mental health concerns in their patient population. When knowledge gaps are addressed, care of pediatric mental health disorders by pediatricians may improve.

With perceived lack of knowledge and limited training reported in the literature as a barrier to pediatricians’ providing evidence-based care for childhood mental health disorders, little research exists on beliefs and potential stigma pediatricians may have when faced with treating these disorders.3 Each physician within medicine carries their own history and personal experiences that invariably will influence their practice patterns and interactions with patients.19 Stigma, defined as disapproval or discrimination against a person based on perceivable characteristics that distinguish them from others, is established as a barrier to care for patients with mental health disorders.20,21 Mental health disorders, particularly in children, perhaps because of limited understanding regarding etiology and treatment, are highly stigmatized, even among healthcare professionals.22 In contrast, compassion and care for children is a frequently cited reason medical trainees choose pediatrics as a career.23 Understanding the beliefs pediatricians have regarding youth mental illness provides an opportunity to bridge the gap between the compassion pediatricians cite as a reason they chose to work with children and the vulnerable youth with mental health disorders that are in need of high-quality care.

We conducted this scoping review to establish the current state of the evidence regarding pediatrician-based stigma towards mental health disorders as it impacts the diagnosis, management, and treatment of children and adolescents with mental health conditions.

Methods

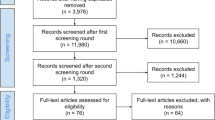

We performed a scoping review to examine the state of the current research on pediatrician stigma towards mental health disorders. We searched for new research in the past 10 years in the following search engines: PsycInfo, PubMed Medline, CINAHL, Ovid Medline, and Embase for bias and stigmatization of mental disorders in practice patterns of pediatricians. General search terms used included: pediatrician, stigma, implicit bias, mental health, judgment, practice pattern, and attitudes of health personnel. Full search strategies are provided in Supplementary S1 for all five databases. One author identified duplicate titles to be excluded (initials M.N.), with feedback from the review team (initials M.K.M., S.M.I., D.M.D.). Two authors (S.M.I. and D.M.D.) reviewed title and abstracts for inclusion in the final review. All full-text articles were reviewed through an iterative process (Fig. 1) by three reviewers (S.M.I., D.M.D., or M.K.M.) and disagreements between exclusions were resolved by the senior reviewer (M.K.M.). New research studying attitudes and beliefs of pediatricians who worked with children and adolescents (ages birth to 18 years) with psychiatric illness were included.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) >18-year-old patient population, (2) neonates/infants, (3) nonpsychiatric diagnoses, (4) self-stigma, (5) nonspecific pediatric mental health providers, (6) not studying medical providers, (7) not studying psychiatric disorders, (8) navigating referrals to mental health, (9) not studying mental health stigma, (10) social stigma, and (11) not solely pediatricians.

Results

Demographics of included studies

Our initial search produced 457 titles with the exclusion of 434 based on the review of title and abstract. Twenty-three full-text articles were included for full-text review. Eight full-text manuscripts met the full inclusion criteria (Table 1).

The total sample of primary care pediatricians was 1571. Females outnumbered males in all eight studies; however, one study did not separate out the percentage of master’s level healthcare workers and pediatricians.19 In that study, there were 1197 total participants, of which 788 were general pediatricians. These demographics were not further broken down into the percentage of female/male physicians. As shown in Fig. 2, physician-specific data on sex for all eight studies were as follows: F: 1111, 57.7%; M: 806, 41.8%; not specified: 9, 0.5%.

There were seven studies completed in the United States of America and one study completed in Ireland.10 Of these, four utilized the American Academy of Pediatrics to send out surveys to providers, one used the NPI database; three used local studies of community health centers and/or academic settings. The mixed-method study completed in Ireland was part of a national survey. As depicted in Fig. 3, four of eight studies broke down pediatrician demographics by race, while the other studies did not specify.

Most of the studies did not further specify the demographics of patients being seen by the studies’ pediatricians. Of the eight studies, one reported on the approximate number of patients seen per week per provider1 with a range of 16–150 patients and median of 86.23 with a standard deviation of 30.75. There were two additional studies that both reported on patient ethnicity and insurance type. From one of these studies, Horowitz et al.24 reported that 75% of pediatricians had a population that was of ≥75% Caucasian, and 56.45% of pediatricians had <80% patients with private insurance and 23.3% patients with private insurance.24 Stein et al.25 reported of their 447 pediatricians, 34.1% cared for a patient population ≥75% Caucasian. There were 48.9% PCPs with <80% patients with private insurance in their practice and 37.6% were treating a population encompassing ≥80% of patients with private insurance.25

Descriptive results of included studies

Pediatrician role

A common theme throughout the included studies was a lack of overall agreement on the role of primary care pediatricians in identification, management, and treatment of pediatric mental health disorders.1,12,24,25 This was in conjunction with noted discomfort with medication management of mental health disorders and lack of training in medication management and/or counseling.9 In different free-text response options, there were beliefs that “ADHD is secondary” within pediatrics.10 There is also varying comfort with diagnosis and treatment, based on patient presentation.12 One study suggested the majority of pediatricians studied believe that pediatricians should be screening for ADHD (91%); however, this did not correlate in practice with only 67% reportedly inquiring about ADHD symptoms in their patients. Pediatricians more likely to screen for ADHD were subsequently found to be more likely treating ADHD.25

Screening and appointment time

Pediatricians note using different screening tools based on different age ranges, such as Pediatric Symptom Checklist and Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). However, primary care pediatricians have concerns about patients and families misinterpreting the questions and translations not giving the same meanings.9 There was also concern about the time constraints of appointment times, factoring into the use of screenings and the ability to review them effectively with families. Time constraint with appointments also led to concerns with factoring in other treatment modalities, such as whether to include medication or counseling in the appointment on top of screening.2,10,24

Treatment options

Primary care pediatricians ranked medication as the most available treatment option.1 Albeit, while the medication is the most available treatment, there is limited comfort in prescribing and inconsistency among pediatricians in prescribing medication for diagnoses other than uncomplicated ADHD.9 However, one study noted that child and adolescent psychiatrists are more likely to initiate medication management for ADHD in comparison to pediatricians.10 With antidepressant prescribing, pediatricians were more likely to prescribe for a patient based on functional impairment and symptom severity.4

Patient/parent perception

Primary care pediatricians were also surveyed on their beliefs of how parents acknowledged treatment options. Per Dempster et al.,1 pediatricians perceived parents would be the most accepting of community-based treatment over hospital-based treatment or parent training. Also noted in the study, the more likely primary care pediatricians felt medication could improve behavior, the more likely that physician was to prescribe medication treatment.

It was reported that if available, pediatricians would recommend hospital-based and community-based treatment.1 Primary care pediatricians also noted parent training as an efficacious option for treatment; however, they were more likely to refer out to community-based treatment.1 This discrepancy could be based on concern that parents might be less compliant or satisfied with a referral for parent training.

Access and referral

Per Dempster et al.,1 pediatricians reported belief in management options of therapy and/or medication as an effective treatment for psychosocial concerns. In this study, primary care pediatricians were more likely to refer to a specialist rather than watch and wait or manage themselves with counseling or medication. It was also perceived that medications were more readily available when compared to community-based treatment modalities.

Pediatricians believed that behavior was more likely to improve with community-based treatment, parent training, or hospital-based treatment in comparison to medication management.1,2 There was also the acknowledgement of limited outpatient child and adolescent psychiatric services.2 Availability of referral to individual therapy can impact prescribing practices as well. When access is poor, one study reported pediatricians were more likely to prescribe psychotropic medication to manage symptoms. However, they were less likely to prescribe antidepressants for anxiety when compared to depression.4

Discussion

This scoping review of pediatrician stigma related to mental health disorders identified eight studies with a combined sample of 788 general pediatricians across the United States and Europe. While many studies have reviewed, which external factors may cause unease or lack of knowledge in screening, diagnosis, and management of mental health disorders in the pediatric setting, only a limited number of studies look into physician-based perceptions, biases, or stigma. There is still no consensus among primary care pediatricians regarding their role in diagnosis, treatment, and management of mental health disorders.1,12,24,25 As confirmed within this scoping review, it is also mirrored within the varying degrees of pediatrician training in mental health management throughout the medical system.2,9,10 Variation in mental health management is revealed in separate clinics, as well as among providers within the same clinic, each with varying levels of comfort with and different preferences in treatment modalities when managing children with mental health conditions.9,10

Compared to other mental health disorders, there appeared to be a fundamental difference in mindset towards diagnoses such as ADHD, where the focus is specifically on treating the child’s symptoms without looking at the potentially large, additional impact of the disorder within the academic, nuclear family, and social settings.25 It was also noted that pediatricians perceive anxiety to have less comorbidities, particularly in comparison to depression. This perception is significant as primary care pediatricians may be less likely to treat anxiety in comparison to depression, although untreated anxiety is associated with increased suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and risk of developing depression.4

A large barrier in the current pediatric setting is how much clinical acumen has to be focused and applied within short clinic appointments, with little time to discuss additional concerns or further screening for more comprehensive assemblage of mental health disorders in patients along with administrative tasks and additional screening.9,15,24 This is troublesome due to a large plurality of children and adolescents with chronic or new-onset mental health disorders currently not getting treatment and with the reported belief that medication is the most readily available treatment modality.9,24 Free-text portions of studies of this scoping review revealed a lack of interest in further training or knowledge about childhood mental health from pediatricians, which is worrisome considering the widespread and growing psychiatric concerns in childhood and adolescence, with decreased availability of community services and specialists.9,24

There is additional concern by pediatricians that they are less confident in prescribing medications for diagnoses such as ADHD, depression, and anxiety. This is reported frequently in terms of confidence or comfort, but these concerns may be influenced by personal bias or stigma towards how to treat said diagnoses or towards medication as a viable treatment option.1,9,25 The potential for bias or stigma to affect mental health management is troublesome, as depression is often treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in hopes to prevent serious outcomes such as suicidal ideation or suicide attempts, but this class of medication is less likely prescribed for anxiety in the primary care setting, which when left untreated may lead to similar outcomes.4

There are also different approaches between pediatricians and child and adolescent psychiatrists during assessment and treatment of mental health. Both fields have barriers in accessibility to additional services, such as individual therapy and occupational therapy.1,10 One study reported pediatricians are less likely to gather collateral from school districts.10 Pediatricians noted improvement in their comfort level in managing mental health with the ability for collaboration with mental health providers during treatment.12 Often times, in child and adolescent psychiatry there are uncomfortable but important discussions about the family dynamic and/or patient–guardian, and even patient–sibling, relationships that factor into management. These discussions are potentially time consuming but can benefit the trajectory of treatment immensely with large gains to the patient–guardian dyad being treated. It would benefit all physicians managing and treating pediatric mental health to have the time to and feel comfortable with addressing the family as a whole, as it is often vitally important in the ability of a child to have an improvement in their mental health.

Conclusion

Overall, it is imperative that primary care pediatricians gain the skills needed or become more comfortable with the diagnosis and management of mental health disorders as the number of children in need of services continues to grow. These skills include education of patients and parents, along with medication management and knowledge of when to refer to a subspecialist in child and adolescent psychiatry or to additional mental health services within the community.

This scoping review is limited by capturing studies primarily completed in the United States, which may limit its generalizability. Physician speciality was limited to pediatricians to allow for under 18 patient population, which did not allow the inclusion of family medicine who also take care of a large mental health patient population. Multiple studies reviewed enlisted the use of surveys through national associations, which may have skewed responses as not all pediatricians are members. While many of the studies discussed perceptions, discomfort, beliefs, and attitudes, the word “stigma” was not used in most studies. This variability in wording, as well as lack of use of the word “stigma,” lends credibility to the idea that physicians and even researchers studying physicians may have some discomfort in discussing the stigmatization of mental health treatment in pediatric primary care settings. This variability in word use also prolonged the review process, as the terminology in the articles made it difficult to determine meaning, specifically whether the discussion was about stigma or about ability and /or knowledge with a topic. As such, initially the authors attempted to err on the side of caution and include several abstracts for full-text review, when they were ultimately excluded. From this study, we now know there is a difference in language among medical specialities that could be further qualitatively researched to better understand the use of physician language, especially regarding words, such as perception, stigma, and bias. Understanding how this difference in language and word preference impacts patient care could be another future direction of our research.

Generally, the use of the word “stigma” was uncommon in the articles reviewed. While there were discussions of perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, and comfort that are all within the realm of stigma, it is essential for a physician to be able to reflect and recognize personal perceptions of the patient population under their care. These abilities allow for recognition of personal limitations that may hopefully allow a physician to be more cognizant of biases, and thus more intentional with specific patient care. With limited data on pediatrician stigma towards mental health, including their role in diagnosis, treatment, and management, more studies are needed to further understand how this is impacting patient care.

In all facets of medicine, the field at large could benefit from continued studies into physician stigma and how it interacts with patient care in all settings. This could be further completed by comparing changes/knowledge transfers between fields with the current move towards more collaborative and integrated care models and potential impact on stigma. It would be valuable to examine if barriers of time, broad scope of practice, and administrative tasks are exacerbated by the stigmatization of mental illness, from perceptions of primary care pediatricians, child and adolescent psychiatrists, and guardians/caregivers. In pursuit of this goal in future research, at the very least we aim to improve how we serve this vulnerable patient population.

References

Dempster, N. R., Wildman, B. G. & Duby, J. Perception of primary care pediatricians of effectiveness, acceptability, and availability of mental health services. J. Child Health Care 19, 195–205 (2015).

Nasir, A., Watanabe-Galloway, S. & DiRenzo-Coffey, G. Health services for behavioral problems in pediatric primary care. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 43, 396–401 (2016).

Brauner, C. B. & Stephens, C. B. Estimating the prevalence of early childhood serious emotional/behavioral disorders: challenges and recommendations. Public Health Rep. 121, 303–310 (2006).

Tulisiak, A. K. et al. Antidepressant prescribing by pediatricians: a mixed-methods analysis. Curr. Probl. Pediatr. Adolesc. Health Care 47, 15–24 (2017).

Green, C. et al. Do subspecialists ask about and refer families with psychosocial concerns? A comparison with general pediatricians. Matern. Child Health J. 23, 61–71 (2019).

O’Brien, D. et al. Barriers to managing child and adolescent mental health problems: a systematic review of primary care practitioners’ perceptions. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 66, e693–e707 (2016).

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Workforce: A Critical Shortage and National Challenge https://www.aacap.org/aacap/resources_for_primary_care/workforce_issues.aspx (2019).

American Academy of Pediatrics. Mental Health Initiatives https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/Mental-Health/Pages/About-Us.aspx (2019).

Hacker, K. et al. Pediatric provider processes for behavioral health screening, decision making, and referral in sites with colocated mental health services. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 34, 680–687 (2013).

Honorio Neto, F. et al. Attitudes and reported practice of paediatricians and child psychiatrists regarding the assessment and treatment of ADHD in Ireland. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. 35, 181–191 (2018).

Connors, E. H. et al. When behavioral health concerns present in pediatric primary care: factors influencing provider decision-making. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 45, 340–355 (2018).

Pidano, A. E. et al. Different mental health-related symptoms, different decisions: a survey of pediatric primary care providers. J. Child Fam. Stud. 26, 3525–3534 (2017).

Bauer, N. S. et al. Computer decision support changes physician practice but not knowledge regarding autism spectrum disorders. Appl. Clin. Inf. 6, 454–465 (2015).

Behrman, G. U. et al. Improving pediatricians’ knowledge and skills in suicide prevention: Opportunities for social work. Qualitative. Soc. Work 18, 868–885 (2018).

Sheldrick, R. C., Mattern, K. & Perrin, E. C. Pediatricians’ perceptions of an off-site collaboration with child psychiatry. Clin. Pediatr. 51, 546–550 (2012).

Kolko, D. J. & Perrin, E. The integration of behavioral health interventions in children’s health care: services, science, and suggestions. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 43, 216–228 (2014).

Baum, R. A., King, M. A. & Wissow, L. S. Outcomes of a statewide learning collaborative to implement mental health services in pediatric primary care. Psychiatr. Serv. 70, 123–129 (2019).

Diamond, G. S. et al. Attitudes, practices, and barriers to adolescent suicide and mental health screening: a survey of pennsylvania primary care providers. J. Prim. Care Community Health 3, 29–35 (2012).

Hajjaj, F. M. et al. Non-clinical influences on clinical decision-making: a major challenge to evidence-based practice. J. R. Soc. Med. 103, 178–187 (2010).

Bouchard, L. E. & MacLean, R. Acknowledging stigma. Can. Fam. Physician 64, 91–92 (2018).

Bravo-Mehmedbasic, A. & Kucukalic, S. Stigma of psychiatric diseases and psychiatry. Psychiatr. Danub. 29(Suppl. 5), 877–879 (2017).

Achenbach, T. M. & Edelbrock, C. S. Psychopathology of childhood. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 35, 227–256 (1984).

Goodyear, H. M. et al. Choosing a career in paediatrics: do trainees’ views change over the first year of specialty training? JRSM Open 5, 2054270414536552 (2014).

Horwitz, S. M. et al. Barriers to the identification and management of psychosocial problems: changes from 2004 to 2013. Acad. Pediatr. 15, 613–620 (2015).

Stein, R. E. et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: how much responsibility are pediatricians taking? Pediatrics 123, 248–255 (2009).

Brown, J. D. & Wissow, L. S. Disagreement in parent and primary care provider reports of mental health counseling. Pediatrics. 122, 1204–1211 (2008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M.I., D.M.D., M.K.M., and M.N. all had substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. S.M.I. and D.D. drafted the article with the aforementioned, along with M.K.M. revising it critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version to be published was by M.K.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.K.M. has received research grants from UH CRC, grant funding from The Hartwell Foundation; research funding from Allergan Pharmaceuticals; research support from the Neurologic and Behavioral Outcomes Center, CWRU, and royalties from the APA. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Imfeld, S.M., Darang, D.M., Neudecker, M. et al. Primary care pediatrician perceptions towards mental health within the primary care setting. Pediatr Res 90, 950–956 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-01349-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-01349-7

- Springer Nature America, Inc.

This article is cited by

-

Multilevel perspectives on the implementation of the collaborative care model for depression and anxiety in primary care

BMC Psychiatry (2024)

-

Provider Perspectives on an Integrated Behavioral Health Prevention Approach in Pediatric Primary Care

Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings (2023)