Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the association between prenatal maternal health and socioeconomic status (SES) and health-related quality of life (QoL) among 10-year-old children born extremely preterm.

Design/ methods

Retrospective analysis of the Extremely Low Gestational Age Newborns (ELGAN) Study cohort of infants born < 28 weeks gestational age. QoL was assessed at 10 years of age using the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory. Multivariate regression models were used for analyses.

Results

Of 1198 participants who survived until 10 years of age, 889 (72.2%) were evaluated. Lower maternal age, lack of college education; receipt of public insurance and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) were associated with lower QoL scores. Specific maternal health factors were also associated with lower child QoL scores.

Conclusions

Specific, potentially modifiable, maternal health and social factors are associated with lower scores on a measure of parent-reported child QoL across multiple domains for children born extremely preterm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Advances in neonatal-perinatal medicine over the last few decades have improved the survival rates of infants born extremely preterm (less than 28 weeks’ gestation) [1, 2]. Yet these preterm survivors are at high risk for long-term physical, cognitive, and psychosocial impairments [2, 3]. Because of the recognition that infants born extremely preterm are at risk for significant long-term morbidities, many researchers have focused on preventing severe neonatal morbidities in these vulnerable preterm infants during their NICU birth hospitalizations. Additionally, early identification of high risk infants allows for early institution of intervention strategies during infancy and early childhood. These efforts have led to the welcome news of higher rates of infants born extremely preterm reaching adulthood with better health outcomes across the life course [4, 5].

Saigal et al. tried to identify factors that improve the health-related quality of life (HRQL) of patients and mitigate the impact of impairment [6]. HRQL incorporates patient and caregiver perspectives regarding health status across physical, social, emotional, and school domains, and the effects of physical and social factors on quality of life (QoL). HRQL aligns directly with the World Health Organization’s definition of health as “the complete state of physical, mental, and social well-being, not merely the absence of disease” [7]. High HRQL in adolescence is strongly associated with self-efficacy and self-esteem, while low HRQL is associated with loneliness and stress [8, 9]. Multiple long-term neonatal follow-up studies have shown lower quality of life among children and adolescents born extremely preterm compared to age-matched peers, as well as a linear relationship between higher neurodevelopmental functioning and higher quality of life [10,11,12].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the association between prenatal maternal health and socioeconomic status (SES) factors and QoL among 10-year-old children born extremely preterm. We hypothesized that maternal factors, specifically SES and health, will negatively impact QoL for infants born extremely preterm.

Methods

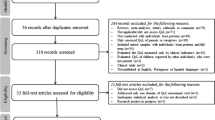

Cohort selection

This report follows the guidelines of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [13]. Between 2002 and 2004, women giving birth at 28 weeks of gestation or earlier at one of 14 academic medical centers throughout the US were enrolled in the Extremely Low Gestational Age Newborn (ELGAN) study. Maternal consent was gathered upon hospital admission or near delivery. Each participating institution received institutional review board (IRB) approval for protocols used during the study. Approximately 85% of mothers approached for participation in the original ELGAN study consented to participate, resulting in a cohort of 1249 mothers and 1506 infants. Of the 1506 infants, 1198 (80%) survived to age 10 years. Among those, in 889 (74.2%) children we carried out a battery of tests for assessing autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and parental reports on child behavior, development and seizures [14].

Within a few days of the delivery of the ELGAN participant, a research assistant interviewed the mother using a structured questionnaire with questions about the mother’s socioeconomic status, medical problems, and medications. The research assistant reviewed mother’s medical record to obtain additional information about the mother’s health and medications, and revised neonates’ records to obtain information about neonatal complications and treatments. Maternal social characteristics included maternal age category ( < 21 years, 21 to 35 years, and > 35 years), maternal education, maternal marital status, maternal insurance type, and Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) eligibility. A composite socioeconomic disadvantage score, ranging from 0 (indicating least disadvantage) to 4 (indicating most disadvantage), was also defined as an indicator for the level of socioeconomic hardship mothers’ had by the total presence of the following four socioeconomic conditions: education (less than high school), marital status (not married or not living together), insurance (public insurance or no insurance), and SNAP eligibility.

Maternal health characteristics included body mass index (BMI) categories (underweight: <18.5, healthy weight: 18.5 to 25, overweight: > 25 to 30, and obese: > 30), pre-pregnancy diagnosis of asthma and diabetes, and pre-pregnancy/pregnancy/delivery hypertension symptoms. Potentially life-threatening maternal pregnancy complications and indications for premature delivery, as well as Hemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes and Low Platelets (HELLP) syndrome and preeclampsia, were included. A composite variable was defined as having displayed any of the aforementioned hypertensive disorders, HELLP, or preeclampsia. Whether mother smoked or was exposed to second-hand smoke during pregnancy was ascertained by maternal interview; and a composite exposure was defined for mothers’ who either smoked or were exposed to second-hand smoke during pregnancy. Maternal cardio-metabolic disorder was defined as having obesity (BMI > 30), any-hypertensive disorder or diabetes mellitus. Newborn gestational age in completed weeks (27 weeks, 25–26 weeks, and 23–24 weeks) as well as birthweight z-scores were also collected.

Ten year follow-up

At the 10-year follow-up visit, HRQL measures were evaluated by a parent or caregiver, most often the mother, who completed the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) 4.0 generic core scales [15]. The PedsQL was designed to measure the core components of quality of life across multiple domains for the child—physical (8 items), emotional (5 items), social (5 items), and school (5 items) functioning— with each item scored on a 5-point Likert scale. These domains were summed and transformed to a linear 0–100 scale, with higher scores corresponding to higher quality of life. The PedsQL total summary score incorporates all areas of functioning (23 items total) and provides a composite quality of life score for the child. The PedsQL has been demonstrated to be reliable and valid in a large population of enrollees in the Children’s Health Insurance Program in California [16].

Maternal psychiatric illness

When study participants were 15 years old, their mother reported on whether they themselves had ever been diagnosed with a psychiatric illness. Since a history of maternal psychiatric illness had not been obtained when their children were 10 years of age, we opted to use maternal psychiatric illness history only during sensitivity analysis.

Statistical analyses

Regression models were used to evaluate the association between QoL scores and prenatal maternal health factors as well as socioeconomic status (SES) factors. For maternal education and marital status variables, both of which consisted of five categories, a secondary set of binary variables- college education and married- were also defined to explore these factors’ associations without the small sample size effects of some categories. In the same regard, the very small number of mothers whose marital status were “widowed” were analyzed with mothers “separated or divorced”, under the “separated or divorced or widowed” category.

The selection of the covariates for inclusion in multivariate analyses was based on results from a directed acyclic graph (DAG; Supplemental Fig. 1) to avoid bias secondary to confounding [17]. DAGs are graphic models for causal relationships; in the current analyses the relevant relationships are between variables related to prenatal maternal health or variables related to maternal socioeconomic status (the exposure variables) and her child’s quality of life at 10 years of age (the outcome variable). The analytic goal is to obtain an unbiased estimate of how strongly the exposure variable influences the outcome variable; towards this goal, potentially confounding factors require adjustment (also referred to as “control of confounding”). DAGs are a tool for identifying the minimum set of variables that require adjustment in order to obtain an unbiased estimate of the strength of the association between exposure and outcome [17]. Daggity is a free online tool that allows the user to specify relationships among variables, based on existing research and/or expert opinion, in order to generate a list of variables that require adjustment [18]. The univariate analysis informed the construction of composite variables for associations of interest: maternal socioeconomic disadvantage score an ordinal variable that increased by 1 for each of the following factors: lack of college education, public insurance, unmarried, and/or SNAP eligibility and maternal cardio-metabolic disorder, defined as the presence of any of the following: obesity defined as BMI > 30, any hypertensive disorder, and/or diabetes. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 889 subjects were included in the study. Prenatal maternal social and health as well as neonatal characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Although a majority of women did not have a college degree, 72% of women had 0 or 1 SES least disadvantage score (meaning a little more than a quarter of them had disadvantageous SES). Within this extremely preterm group, 45% were 25–26 weeks of gestation. In addition, as shown in Supplemental Table 1, about 39% of women had been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder.

Univariate analyses showed that all individual child domain scores except the emotional score and the total summary score for QoL of the child were lower for children of mothers without college education and those eligible for public health insurance or SNAP. Child QoL scores increased with increasing maternal education and increasing maternal age. Married mothers had children with higher QoL scores overall as well as for the individual domains (Table 2).

For maternal health factors, any form of smoking (maternal smoking, passive smoke exposure and/or any smoke exposure) was associated with the lower QoL scores. Additionally, maternal obesity was associated with lower child QoL, while asthma, diabetes and hypertension displayed some association with lower child QoL (Table 3). Neonatal variables of male sex and GA between 23–26 weeks was associated with lower scores for social functioning scale, school functioning scale as well as total summary score (Table 3).

A DAG- informed multivariable analyses were performed (Table 4) for the characteristics that had statistically significant associations in univariate analyses. Mothers’ lack of a college education was associated with lower child QoL scores in all domains except the emotional functional scale. Mothers’ being married was associated with higher physical health and school functioning scores. Child QoL scores were negatively associated with the maternal socioeconomic disadvantage score, and the associations were mostly stronger for higher scores (most disadvantaged mothers). This relationship became insignificant at the highest SES disadvantage, possibly due to decreased sample size within this category. Lower child QoL scores were associated with maternal cardio-metabolic disorders as well as a history of a maternal psychiatric disorder (data obtained when probands were age 15 years). Maternal asthma was associated with only two of five score domains, and notably, a history of a maternal psychiatric disorder was associated with lower child QoL across all categories (physical, emotional, social, school, and total). Passive smoke exposure and maternal smoking were no longer significantly associated with child QoL scores (Table 4). Of the newborn characteristics, gestational age less than 27 weeks was significantly associated with lower scores on most child QoL scales (Table 4).

Discussion

In this large prospective cohort of infants born extremely preterm, we identified potentially modifiable maternal social and health factors that are associated with lower parent reported QoL scores in multiple domains of child QoL outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first study to address the relationship between maternal health and social conditions and child QoL in an extremely preterm birth cohort. Unique to pediatric studies, participants are dependent on, and under large influence of, caregivers [19]. Elucidating social factors impacting maternal health more broadly identifies factors impacting the family unit [19]. Additionally, maternal health status may have direct and indirect effects on child health status and indirectly impact the primary caregiver’s ability to care and provide for the child [20,21,22]. Greater characterization of maternal factors impacting child QoL may help physicians identify and support the needs of infants born extremely preterm at birth and beyond to improve their QoL across the life course.

Recent work from the Healthy Passages study of elementary-age school children shows parental SES (defined using education level and total household income), as well as factors such as family cohesion, parental nurturance, other adult, and peer support, are positively associated with child QoL across all racial/ethnic categories, and when adjusted for SES status, many (but not all) HRQL differences across racial/ethnic categories become insignificant [23,24,25,26]. In our cohort, we found similar results, and once adjusted for SES factors race and ethnicity no longer correlated with the child QoL outcomes. This highlights the fact that disparities in the outcomes are probably a function of the unfavorable social environments, and health care barriers as well as resources accessible to the minority population. As hypothesized, lower SES factors (no college education, reliance on public insurance, SNAP eligibility) correlated with lower child QoL scores across most sub-scores (physical, emotional, social, school) as well as composite (total QoL) domains. Additionally, we found an additive effect of these social factors such that a higher disadvantage score leads to a greater magnitude of negative effect on child QoL across all domains. Mothers who were older ( > 35 years) and were married had children with better QoL scores, perhaps emphasizing the positive impact of access to resources on child QoL.

Additionally, specific maternal health factors were negatively associated with child QoL scores. These included maternal cardio-metabolic status, asthma and most prominently history of any maternal psychiatric illness (Supplemental Table 1). Once adjusted for SES factors, any smoking- related factors (active, passive or any), were no longer significant. The impact of maternal health (via the passage of inherited conditions and genetic predispositions, as well as environmental influence) on child health is well-appreciated, with reports demonstrating direct causal pathways between maternal depression and infant quality of life, as well as smoking behavior directly impacting child asthma [20,21,22]. In addition, it is understood that children raised in a family with low SES status have suboptimal health outcomes [27,28,29,30], and that maternal health burden is associated with lower SES and decreased ability to provide physical and emotional stability within the household [31].

Of the neonatal variables studied, low gestational age was the only variable associated with lower child QoL scores after adjustments. It is established that the earlier infants are born, the greater their risk for morbidity, including neonatal infection and illness, as well as long-term physical, cognitive and mental impairments [32, 33]. Variation in QoL by sex is also a well-documented finding, as prematurely born males have higher risks for cognitive impairments and neurodevelopmental conditions such as ADHD and autism compared with age-matched females [34,35,36,37,38]. The lower performance among male patients in the unadjusted models for the child QoL domains are likely influenced by cognitive ability, and within this same ELGAN cohort, cognitive impairment is more common in boys than girls [11].

These early life factors can be identified prior to birth and during the perinatal period providing multiple opportunities to identify mother-baby dyads and family units that may benefit from increased intervention and support for these modifiable factors. Infants born extremely preterm in addition to being most vulnerable are also exposed to multiple painful stimuli, including but not limited to procedural pain. Inadequate awareness and thus alleviation of pain in this population can have negative impact persisting into childhood. Utilizing maternal-infant dyad bonding as a non-pharmacologic measure can be a great adjunct to pharmacologic measures as recommended by AAP [39]. Research within the field of chronic pain provides a guide; studies have shown positive effects from integrative care interventions targeted to improve QoL and reduce symptom burden [40, 41]. A promising result identified in a cohort of women with chronic pain showed that targeted interdisciplinary interventions improved QoL of largest magnitude in those with low baseline QoL [42]. Recognizing the strength of the associations identified, efforts should focus on providing optimal mental health and behavioral health care to mothers.

Strengths of our study include a large, prospective, multi-center cohort sample that was relatively diverse with respect to sociodemographic attributes. The rigorous design of the original ELGANs study combined with high rate of longitudinal follow-up is also another strength. There also are several limitations. Only extremely preterm individuals were included in the ELGAN Study, so the findings reported here might not apply to children born closer to term gestation. Of the original 1198 survivors, 25.6% of participants were not evaluated at 10 years of age, potentially resulting in selection bias. In this cohort born between the years of 2002–2004, 10-year-old follow-up data is already approximately 10 years old; this is an inherent problem with most long-term follow-up studies. We realize that the maternal psychiatric disorders diagnosis data was collected after the PedsQL data, with some ambiguity about the exact time of diagnosis. However, given the significant impact that it can have on the child’s neurobehavioral outcomes we proceeded with the analysis and found a significant correlation between all domains of QOL. This will need further exploration in future studies. Also, the QoL questionnaires were completed by parents/caregivers who may have a different perception than the subjects themselves.

Conclusion

Among 10-year-old children born extremely preterm, specific maternal social factors including lower maternal age, lack of college education, need for public insurance and SNAP eligibility; and maternal health factors including any smoking, pre-pregnancy obesity, asthma, diabetes, and hypertensive disorders were associated with lower scores on a measure of parent-reported child QoL measures across multiple domains. Focused interventions to support mothers’ SES and health prenatally and postnatally may enhance QoL and long-term health outcomes of children born extremely preterm. This study lays the foundation for future research aimed at addressing the impact of socioeconomic status and caregiver health status on the QoL for infants born extremely preterm in order to maximize quality of life and equitable care.

Data availability

The dataset used for this study is not publicly available as it contains some identifiable information, but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Walsh MC, Carlo WA, Shankaran S, et al. Trends in care practices, morbidity, and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993–2012. JAMA. 2015;314:1039–51.

Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet. 2008;371:261–9.

Wolke D, Johnson S, Mendonça M. The life course consequences of very preterm birth. Annu Rev Dev Psychol. 2019;1:69–92.

Glass HC, Costarino AT, Stayer SA, Brett C, Cladis F, Davis PJ. Outcomes for extremely premature infants. Anesth Analg. 2015;120:1337.

McKenzie K, Lynch E, Msall ME. Scaffolding parenting and health development for preterm flourishing across the life course. Pediatrics. 2022;149

Saigal S, Stoskopf B, Pinelli J, et al. Self-perceived health-related quality of life of former extremely low birth weight infants at young adulthood. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1140–8.

World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization. New York, NY: World Health Organization; 1948. https://www.who.int/about/accountability/governance/constitution.

Mikkelsen HT, Haraldstad K, Helseth S, Skarstein S, Småstuen MC, Rohde G. Health-related quality of life is strongly associated with self-efficacy, self-esteem, loneliness, and stress in 14–15-year-old adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:1–17.

Freire T, Ferreira G. Health-related quality of life of adolescents: relations with positive and negative psychological dimensions. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2018;23:11–24.

Ni Y, O’Reilly H, Johnson S, Marlow N, Wolke D. Health-related quality of life from adolescence to adulthood following extremely preterm birth. J Pediatr. 2021;237:227–236.e5.

Bangma JT, Kwiatkowski E, Psioda M, Santos HP Jr, Hooper SR, Douglass L, et al. Assessing positive child health among individuals born extremely preterm. J Pediatr. 2018;202:44–49.e4.

Baumann N, Bartmann P, Wolke D. Health-related quality of life into adulthood after very preterm birth. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20153148.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Rextremely pretermorting of Observational Studies in Extremely pretermidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for rextremely pretermorting observational studies. J Clin Extrem Pretermidemiol. 2008;61:344–9.

Kuban KC, Josextremely pretermh RM, O’Shea TM, Allred EN, Heeren T, Douglass L, et al. Girls and boys born before 28 weeks gestation: risks of cognitive, behavioral, and neurologic outcomes at age 10 years. J Pediatr. 2016;173:69–75.e1.

Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Seid M, Skarr D. The PedsQL™* 4.0 as a pediatric population health measure: feasibility, reliability, and validity. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3:329–41.

Douglass LM, Kuban K, Tarquinio D, Schraga L, Jonas R, Heeren T, et al. A novel parent questionnaire for the detection of seizures in children. Pediatr Neurol. 2016;54:64–69.e1.

Greenland S, Pearl J, Robins JM. Causal diagrams for extremely pretermidemiologic research. Extrem Pretermidemiol. 1999;10:37–48. 1999

Textor J, Van der Zander B, Gilthorpe MS, Liśkiewicz M, Ellison GT. Robust causal inference using directed acyclic graphs: the R package ‘dagitty’. Int J Extremely Pretermidemiol. 2016;45:1887–94.

Richter L The importance of caregiver-child interactions for the survival and healthy development of young children: a review. 2004. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/924159134X. Accessed October 2023

Behrman JR, Wolfe BL. How does mother’s schooling affect family health, nutrition, medical care usage, and household sanitation? J Econ. 1987;36:185–204.

Darcy JM, Grzywacz JG, Stextremely pretermhens RL, Leng I, Clinch CR, Arcury TA. Maternal dextremely pretermressive symptomatology: 16-month follow-up of infant and maternal health-related quality of life. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:249–57.

Weitzman M, Gortmaker S, Walker DK, Sobol A. Maternal smoking and childhood asthma. Pediatrics. 1990;85:505–11.

Weitzman M, Gortmaker S, Sobol A. Maternal smoking and behavior problems of children. Pediatrics. 1992;90:342–9.

Wallander JL, Fradkin C, Chien AT, Mrug S, Banspach SW, Davies S, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in health-related quality of life and health in children are largely mediated by family contextual differences. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12:532–8.

Wallander JL, Fradkin C, Elliott MN, Cuccaro PM, Tortolero Emery S, Schuster MA. Racial/ethnic disparities in health-related quality of life and health status across pre-, early-, and mid-adolescence: a prospective cohort study. Qual Life Res. 2019;28:1761–71.

Wright JP, Dietrich KN, Ris MD, Hornung RW, Wessel SD, Lanphear BP, et al. Association of prenatal and childhood blood lead concentrations with criminal arrests in early adulthood. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e101.

Scott SM, Wallander JL, Elliott MN, Grubaum JA, Chien AT, Tortolero S, et al. Do social resources protect against lower quality of life among diverse young adolescents? J Early Adolesc. 2016;36:754–82.

Rajmil L, Herdman M, Ravens-Sieberer U, Erhart M, Alonso J, Group EK. Socioeconomic inequalities in mental health and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in children and adolescents from 11 European countries. Int J Public Health. 2014;59:95–105.

Xiang L, Su Z, Liu Y, Huang Y, Zhang X, Li S, et al. Impact of family socioeconomic status on health‐related quality of life in children with critical congenital heart disease. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e010616.

Zeller MH, Modi AC. Predictors of health‐related quality of life in obese youth. Obes. 2006;14:122–30.

Aspesberro F, Mangione-Smith R, Zimmerman JJ. Health-related quality of life following pediatric critical illness. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41:1235–46.

Hardie JH, Landale NS. Profiles of risk: maternal health, socioeconomic status, and child health. J Marriage Fam. 2013;75:651–66.

O’Shea TM. Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cerebral palsy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51:816–28. Dec

Kuban KC, O’Shea TM, Allred EN, Paneth N, Hirtz D, Fichorova RN, Leviton A, ELGAN Study Investigators. Systemic inflammation and cerebral palsy risk in extremely preterm infants. J Child Neurol. 2014;29:1692–8.

Linsell L, Malouf R, Morris J, Kurinczuk JJ, Marlow N. Prognostic factors for poor cognitive development in children born very preterm or with very low birth weight: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:1162–72.

Josextremely pretermh RM, O’Shea TM, Allred EN, Heeren T, Hirtz D, Paneth N, et al. Prevalence and associated features of autism spectrum disorder in extremely low gestational age newborns at age 10 years. Autism Res. 2017;10:224–32.

Leviton A, Hooper SR, Hunter SJ, Scott MN, Allred EN, Josextremely pretermh RM, et al. Antecedents of screening positive for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in ten-year-old children born extremely preterm. Pediatr Neurol. 2018;81:25–30.

Halladay AK, Bishop S, Constantino JN, Daniels AM, Koenig K, Palmer K, et al. Sex and gender differences in autism spectrum disorder: summarizing evidence gaps and identifying emerging areas of priority. Mol Autism. 2015;6:1–5.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Fetus and Newbon and Section on Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine. Prevention and management of procedural pain in the Neonat: an update. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20154271.

Loke H, Harley V, Lee J. Biological factors underlying sex differences in neurological disorders. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2015;65:139–50.

Flanagan S, Damery S, Combes G. The effectiveness of integrated care interventions in improving patient quality of life (QoL) for patients with chronic conditions. An overview of the systematic review evidence. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:188.

Björnsdóttir SV, Arnljótsdóttir M, Tómasson G, Triebel J, Valdimarsdóttir UA. Health-related quality of life improvements among women with chronic pain: comparison of two multidisciplinary interventions. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:828–36.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Msall’s efforts were also supported in part by funding from The Health Resources and Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services (UA6MC32492), the Life Course Intervention Research Network. Preterm Research Node: Engaging Families of Preterm Babies to Optimize Thriving and Well-Being.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (grants 5U01NS040069-05 and 2R01NS040069-09) and the Office of the Director of the National Institutes of Health (1UG3OD023348-01). Dr. Frazier has had research support from Healx, Quadrant, and Tetra Pharmaceuticals. All other authors have no financial relationships or any other conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CC, TMO and RS drafted the original manuscript and conceived and designed the study, contributed to data acquisition and analysis, and finalized the manuscript. AO contributed to data analysis; critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for intellectual content. ETJ, JAF, RV, JS, SG, MEM, SK, IJ and RCF contributed to data acquisition and analysis; critically reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Call, C., Oran, A., O’Shea, T.M. et al. Health-related quality of life at age 10 years in children born extremely preterm. J Perinatol 44, 835–843 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-024-01987-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-024-01987-3

- Springer Nature America, Inc.