Abstract

This is the second article in a seven-part series in the Journal of Perinatology that aims to critically examine the current state of Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine (NPM) fellowship training from the structure and administration of a program, to the clinical and scholarly requirements, and finally to the innovations and future careers awaiting successful graduates. This article focuses on the current clinical requirements; recent changes to the clinical environment and their effect on learning; and additional challenges and opportunities in clinical education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Recent changes including duty hour restrictions and decreased experience of residents entering fellowship have affected the amount of time that fellows have to cultivate their clinical skills [1,2,3,4]. New challenges to clinical training include fewer procedural opportunities, more healthcare providers working within the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), and a more complex patient population. NPM fellowship programs vary in how they provide clinical training. In this section of the review, we will explore the current state of clinical education and experience of NPM fellows and how they are being prepared to practice independently in this changing world of NPM.

Common clinical models and current clinical requirements for NPM fellowship

The clinical requirements for fellowship training in NPM are determined by the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP). According to the ACGME, NPM training programs must be a minimum of 36 months, with a minimum of 12 clinical months and 12 months of scholarly activity [5]. Additionally, the ABP mandates that continuous time away from training must be less than 1 year and that absences greater than 3 months require an extension of training for the duration of absence. Program directors (PDs) must verify clinical competency to the ABP annually and upon completion of training [6]. NPM fellowship programs are required to develop program-specific aims consistent with the mission of their sponsoring institution. Competency-based goals and objectives for clinical education should allow for supervised but progressively increasing independence during patient care. Beyond these fundamentals, requirements for the clinical curriculum of NPM training programs is far less prescriptive. Although fellowship programs are required to obtain objective metrics demonstrating clinical competence, the specifics of achieving this proficiency are determined by each individual program.

A 2019 survey of 59 U.S. NPM fellowship PDs demonstrated variation in the structure of the clinical experience during fellowship. The number of clinical blocks reported varied from 12 to 18 months with a wide range of 90 to more than 175 night calls over the course of a 3-year training program. Approximately half of respondents reported fellows are supported by an “in-house” attending while on night call [7]. The ACGME stipulates that all NPM fellows must “participate in follow-up of high-risk neonates” following discharge from the NICU. According to the 2020 program requirements, “A sufficient number of discharged infants must be available in a NICU follow-up clinic to ensure an appropriate longitudinal outpatient experience for each fellow.” The requirements do not specify the frequency or nature of this experience [5]. Consequently, PDs reported variability in follow-up clinic exposure with programs ranging from fewer than 20 to more than 45 half-day clinics over 3 years [7].

Further guidance from the ACGME is provided in the form of expectations for graduates. This has allowed programs to develop curricula that suit their circumstances and to ensure that fellows receive the full breadth of experiences they need to become qualified neonatologists. For example, there is the expectation that “fellows must be skilled in the preparation of neonates for transport” [5]; however, there is no specific requirement for NPM fellows to directly participate in the transportation of critically ill neonates. While the majority of fellowship directors (83%) reported that fellows take transport calls from referring institutions, determinants of “competency” to direct transports differed among programs [7].

Similarly, the ACGME program requirements state that fellows must demonstrate procedural skills in neonatal resuscitation, umbilical catheterization, endotracheal intubation, and evacuation of air leaks [5]. Determination of procedural competency is difficult to define, and thus benchmarks to determine proficiency are not standardized across programs or by the ACGME. 58% of program directors surveyed in 2019 reported that they require a specific number of successful procedures prior to graduation, while the remainder did not specify metrics utilized to assess procedural competency [7].

Recent changes in clinical environment and impact on clinical education

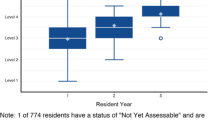

The NICU clinical and learning environment has changed drastically over the past decade (Fig. 1). In 2003, the ACGME established duty hour standards to promote high-quality education and safe patient care. These standards included an 80-hour weekly limit averaged over four weeks and a 24-hour limit on continuous duty, with up to six added hours for continuity of care and education [1]. The updated 2011 ACGME duty hour standards allowed for trainees to remain beyond their scheduled duty period to provide care to a single patient in unusual circumstances, including critical status or humanistic needs of a patient or family [1]. With these duty hour restrictions and limited exposure to intensive care rotations, residents have less procedural experience and less competence in life-saving skills [2, 8]. The result is residents entering NPM fellowship who are less prepared than in previous years [2,3,4]. In a 2017 survey, first-year NPM trainees generally felt prepared for fellowship in professionalism and clinical areas, but voiced concerns in the psychomotor domain [2]. These concerns were echoed by NPM PDs in a 2016 study with the majority ranking new fellows negatively across all ACGME required neonatal skill competencies [3].

Duty hour restrictions coupled with progressively more complex infants with longer hospital stays has placed increasing pressure on the NICU workforce [9]. A 2012 survey found that in response to the duty hour restrictions, more clinical responsibilities were shifted to attendings, neonatal nurse practitioners (NNPs), physician assistants (PAs), and hospitalists with hospital administration intent to continue this trend [9]. This burgeoning of mid-level providers with their respective trainees and even the emergence of Pediatric Hospitalist Medicine fellowships has increased the number and variety of learners in the NICU adding further strain to the overall training environment. Already less prepared upon entering fellowship, NPM fellows now must share procedural opportunities with residents, other subspecialty fellows, non-physician trainees, and existing providers seeking to maintain competence; thus, creating a self-perpetuating cycle.

Increased focus on patient safety has also led to several changes affecting fellow procedural training. Adverse events are common with neonatal intubation and increase in frequency with increased attempts [10]; therefore, fellows are no longer given numerous attempts if a skilled provider is present. They are also often not given the first attempt at anatomically difficult airways if technology and expertise are available. More training programs are using video laryngoscopy for airway education [11] with difficult airway patients being intubated more frequently by ENT using fiberoptic laryngoscopy. Furthermore, with the 2015 Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP) 7th edition recommendations against routine tracheal suctioning of non-vigorous infants born with meconium-stained amniotic fluid [12], the overall number of intubations in the delivery room has declined, which further decreases opportunities for trainees to practice this life-saving skill [13]. In addition, peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) teams and placement bundles are being created to reduce Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections (CLABSIs). This has been shown to decrease CLABSI rates but gives fellows less opportunity to insert PICC lines [14]. Procedural opportunities are still available but are less frequent given the focus on patient safety and not on fellow education.

As such, simulation-based training has become more common to ensure adequate exposure and a lower-risk setting [15]. In the 2019 PD survey, over half of responding programs report that their first-year fellows attend a simulation-based boot camp and 42% report sending their second- and third-year fellows to boot camps. The majority of programs also report that their fellows participate in simulation-based educational sessions throughout their training with less than 7% reporting no involvement in simulation exercises [7]. With this increase in use, simulation technology has grown to take on many forms ranging from low-fidelity task trainers to high-fidelity, interactive computer-enhanced mannequins and beyond [15].

In addition to video laryngoscopy and simulation-based technologies, point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has been used in the NICU with increasing frequency as a technology-based adjunct for diagnosis and procedural guidance [16]. POCUS refers to the use of ultrasound at the bedside by non-radiology and non-cardiology practitioners [17]. Common neonatal applications are assessment for pneumothorax [18], pleural effusion [19], presence/size of PDA [20], and central line placement [21, 22]. Evidence continues to build on the utility and accuracy of ultrasound in the ICU setting [21, 23, 24]. However, implementation of POCUS use in the NICU has been slow. There are no guidelines or requirements for fellowship training though programs are beginning to develop curricula [25]. A 2015 survey of fellowship PDs in NPM and pediatric critical care medicine showed that most PDs felt ICU physicians should be able to perform POCUS; however, only 29% of NPM programs provided training to their fellows and only 23% to their attendings. Perceived barriers included liability concerns as well as lack of equipment, instructors, and time [25].

Additional challenges in clinical education and experience

Technological advancements and changes in neonatal practice patterns have improved survival of infants born at the margin of viability and with complex congenital malformations. This in turn has resulted in more NICU infants with technology dependence, prolonged lengths of stay, and complex care needs. This transition into “infantology” has created uncharted territory for Neonatal ICUs and Pediatric ICUs navigating the transition from neonatal focused care to long-term pediatric complex medical care. This changing patient population has contributed to removal of life-sustaining interventions as the leading circumstance of death in regional referral NICUs [26,27,28], requiring fellows to receive training in difficult conversations and end-of-life care. Furthermore, increasing parental use of websites, mobile apps, and social media for health information and medical advice has altered the dynamics of the physician-patient relationship and has helped highlight the importance of joint decision-making [29], further emphasizing the need for education on advanced communication skills [30].

Additionally, with the development of increasingly specialized units, access to the full spectrum of neonatal patients and treatment strategies has changed. Units subspecializing in Neuro-NICU, Cardiac-ICU, fetal diagnosis, chronic lung disease, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, pulmonary hypertension, and ECMO are increasing in number. For example, in 2019 there were 430 ECMO programs, up from 83 programs in 1990 [31]. Other advanced resources such as specialized ventilators including high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV), high-frequency jet ventilation (HFJV), and neurally adjusted ventilatory assist (NAVA) are not ubiquitous. These specialized resources tend to aggregate at units within large academic institutions, which helps centralize resources and expertise benefiting neonates with rare conditions. This is turn may decrease exposure and experience for fellows in smaller programs thereby affecting future proficiency as an attending at other institutions.

Furthermore, mainstream neonatology training has focused on care of the sick or preterm neonate. Traditionally, well-baby nurseries are covered by general pediatricians, with or without mid-level practitioners. Pediatric residents are expected to demonstrate proficiency in taking care of this population during their training [32]. Hence, this is not usually incorporated again into NPM fellowship training. Some procedures such as neonatal circumcisions were frequently performed by pediatricians and neonatologists. Over the last few years, most in-hospital newborn circumcisions are performed by OB-GYN, family practice, and pediatricians [33], with urologists managing complicated cases. Per ACGME, knowledge of this procedure is included in Pediatric and Internal Medicine-Pediatric residency program requirements but not in NPM. In a survey of all NPM fellows enrolled in ACGME-accredited training programs from July 2014 to June 2015, very few NPM fellows (mean 1–2/year) reported experience in circumcision during training [4]. Job opportunities after training, however, may include rounding on well newborns and performing circumcisions, depending on the location and level of the neonatal unit.

Considerations and opportunities

Customization of NPM fellowship training based on preferred career pathway or known job requirements could be considered within training programs. In a 2011 survey of pediatric fellowship PDs, only 42% felt that the time spent on clinical training should be the same for trainees regardless of their intended career path [34]. PDs felt that those pursuing clinician/clinician-educator careers should ideally have 24-months of clinical training versus 12-months for those interested in primarily research careers [34]. According to a survey of NPM PDs, only 17% of programs offer pathways that take this into consideration [7].

With respect to content, within clinical tracks there is potential for customization by incorporating individual goals and future employment plans. For example, fellows planning a career in private practice could be offered rotations in level II or III NICUs as opposed to only at a level IV unit. There may be options for advanced training in ECMO, complex prenatal consultation, or palliative care for those that envision future career niches in these areas. Similarly, most clinicians in academic institutions are expected to be “clinician-educators” with defined roles in medical student, resident, or fellow education. Specialized clinician-educator tracks represent a further streamlining option and could include a curriculum focusing on adult learning theory, curriculum design, simulation, evaluation and assessment, and professional development [35]. “Clinician-scientists” typically have additional training in research and include research as a significant part of their professional career. Traditionally the MD-PhD pathway has been the main route to clinician-scientist training in the U.S., but these opportunities could be offered during fellowship via pathways such as NIH T32 grants. Fellows who plan on careers as physician scientists could be offered more protected research time to pursue projects. Well-defined clinician-scientist track models exist in other countries such as the UK [36].

Physicians are very often required to lead teams in clinical and non-clinical environments. This process begins early with neonatology fellows leading teams in code situations. Effective leadership promotes improved clinical outcomes [37]. Yet there is a lack of emphasis on leadership training in medical school and residency forcing clinicians to learn this skill ad-hoc while on the unit [38]. Development of a fellowship leadership curriculum could include topics such as team management, conflict resolution, and communication. This would provide formal training as well as opportunities to connect learners interested in leadership or administration with practicing clinician-leaders.

Streamlining NPM fellowships will likely require more than adapting the content to the needs of the learner given the evolving clinical environment and time constraints. Clear goals and learning objectives as well as utilization of traditional teaching techniques such as the Socratic method, one minute preceptor, teaching scripts, and bedside presentations can be effective clinical teaching strategies for neonatology trainees [39]. However, additional approaches to medical education that promote active learning and efficiency will be of benefit. “Just-in-time training (JITT),” a focused topic-specific training occurs just prior to implementation [39], and simulation are currently commonly utilized in procedural and resuscitation training but may also prove to be increasingly useful for clinical and communication skills. Recently, the Organization of Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine Training Program Directors (ONTPD) developed a physiology curriculum using a flipped classroom structure with online video modules followed by faculty facilitated group discussion [40]. This nationally available curriculum is a model for time-efficient fellow education that may standardize educational content dissemination via modules but also allow for local context application via group discussion. Further innovations in NPM medical education are described in a separate manuscript in this series.

Conclusion

A main focus of NPM fellowship is to prepare fellows to be proficient neonatologists. Providing thoughtful care, making sound clinical decisions, and skillfully performing procedures are components of clinical care learned in fellowship. Although guidelines are provided by the ACGME and ABP, NPM fellowship programs vary greatly in how they deliver this training. In the changing landscape of neonatology, with diverse patient populations, advanced technologies, and super-specialization within the field, it can be challenging for different programs to provide consistent fellow education. With continued adaptation of educational strategies to the evolving needs of NPM fellows, programs can successfully cultivate the next generation of clinically excellent neonatologists. Future installments in this article series will address topics such as scholarship, evaluation, and education innovation to help further this mission.

References

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME common program requirements (residency) (effective July 1, 2020). 2020. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2020.pdf.

Korbel L, Backes CH Jr., Rivera BK, Mitchell CC, Carbajal MM, Reber K, et al. Pediatric residency graduates preparedness for neonatal-perinatal medicine fellowship: the perspective of first-year fellows. Am J Perinatol. 2020;37:511–8.

Backes CH, Bonachea EM, Rivera BK, Reynolds MM, Kovalchin CE, Reber KM, et al. Preparedness of pediatric residents for fellowship: a survey of US neonatal-perinatal fellowship program directors. J Perinatol. 2016;36:1132–7.

Sawyer T, French H, Ades A, Johnston L. Neonatal-perinatal medicine fellow procedural experience and competency determination: results of a national survey. J Perinatol. 2016;36:570–4.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in neonatal-perinatal medicine (effective July 1, 2020). 2020. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/329_NeonatalPerinatalMedicine_2020.pdf?ver=2020-06-29-162707-410.

The American Board of Pediatrics. Subspecialty certifications and admission requirements. 2020. https://www.abp.org/content/subspecialty-certifications-admission-requirements.

Johnston L. Organization of Neonatal Training Program Directors (ONTPD) Survey 2019: NPM Fellowship Landscape; 2019 (Unpublished).

Gaies MG, Landrigan CP, Hafler JP, Sandora TJ. Assessing procedural skills training in pediatric residency programs. Pediatrics. 2007;120:715–22.

Freed GL, Dunham KM, Moran LM, Spera L. Resident work hour changes in children’s hospitals: impact on staffing patterns and workforce needs. Pediatrics. 2012;130:700–4.

Hatch LD, Grubb PH, Lea AS, Walsh WF, Markham MH, Whitney GM, et al. Endotracheal intubation in neonates: a prospective study of adverse safety events in 162 infants. J Pediatr. 2016;168:62–66 e66.

Silverberg MJ, Kory P. Survey of video laryngoscopy use by U.S. critical care fellowship training programs. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:1225–9.

American Academy of Pediatrics, American Heart Association. Textbook of neonatal resuscitation., 7th ed. edn. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics and American Heart Association; 2016.

Myers P, Gupta AG. Impact of the revised NRP meconium aspiration guidelines on term infant outcomes. Hospital Pediatrics. 2020;10:295–9.

Wang W, Zhao C, Ji Q, Liu Y, Shen G, Wei L. Prevention of peripherally inserted central line-associated blood stream infections in very low-birth-weight infants by using a central line bundle guideline with a standard checklist: a case control study. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:69.

Scalese RJ, Obeso VT, Issenberg SB. Simulation technology for skills training and competency assessment in medical education. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:46–49.

Nguyen J. Ultrasonography for central catheter placement in the neonatal intensive care unit-a review of utility and practicality. Am J Perinatol. 2016;33:525–30.

Moore CL, Copel JA. Point-of-care ultrasonography. N. Engl J Med. 2011;364:749–57.

Liu J, Copetti R, Sorantin E, Lovrenski J, Rodriguez-Fanjul J, Kurepa D, et al. Protocol and guidelines for point-of-care lung ultrasound in diagnosing neonatal pulmonary diseases based on international expert consensus. J Vis Exp. 2019:145;e58990.

Liu J, Ren XL, Li JJ. POC-LUS guiding pleural puncture drainage to treat neonatal pulmonary atelectasis caused by congenital massive effusion. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33:174–6.

Singh Y, Katheria A, Tissot C. Functional echocardiography in the neonatal intensive care unit. Indian Pediatr. 2018;55:417–24.

Franta J, Harabor A, Soraisham AS. Ultrasound assessment of umbilical venous catheter migration in preterm infants: a prospective study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017;102:F251–F255.

Katheria AC, Fleming SE, Kim JH. A randomized controlled trial of ultrasound-guided peripherally inserted central catheters compared with standard radiograph in neonates. J Perinatol. 2013;33:791–4.

Saul D, Ajayi S, Schutzman DL, Horrow MM. Sonography for complete evaluation of neonatal intensive care unit central support devices: a pilot study. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35:1465–73.

Zaghloul N, Watkins L, Choi-Rosen J, Perveen S, Kurepa D. The superiority of point of care ultrasound in localizing central venous line tip position over time. Eur J Pediatr. 2019;178:173–9.

Nguyen J, Amirnovin R, Ramanathan R, Noori S. The state of point-of-care ultrasonography use and training in neonatal-perinatal medicine and pediatric critical care medicine fellowship programs. J Perinatol. 2016;36:972–6.

Michel MC, Colaizy TT, Klein JM, Segar JL, Bell EF. Causes and circumstances of death in a neonatal unit over 20 years. Pediatr Res. 2018;83:829–33.

Hellmann J, Knighton R, Lee SK, Shah PS. Neonatal deaths: prospective exploration of the causes and process of end-of-life decisions. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2016;101:F102–107.

Weiner J, Sharma J, Lantos J, Kilbride H. How infants die in the neonatal intensive care unit: trends from 1999 through 2008. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:630–4.

Smailhodzic E, Hooijsma W, Boonstra A, Langley DJ. Social media use in healthcare: a systematic review of effects on patients and on their relationship with healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:442.

Wald HS, Dube CE, Anthony DC. Untangling the Web-the impact of Internet use on health care and the physician-patient relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;68:218–24.

Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO). ECLS Registry Report International Summary; 2020.

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in pediatrics (effective July 1, 2020). 2020. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/320_Pediatrics_2020.pdf?ver=2020-06-29-162726-647.

Metcalfe P. Teaching neonatal circumcision. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7:265.

Freed GL, Dunham KM, Moran LM, Spera L, McGuinness GA, Stevenson DK. Fellowship program directors perspectives on fellowship training. Pediatrics. 2014;133:S64–S69.

Smith CC, McCormick I, Huang GC. The clinician-educator track: training internal medicine residents as clinician-educators. Acad Med. 2014;89:888–91.

Jenkins S, Bryant C. Clinician scientist fellows scheme evaluation. 2012. https://acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/35282-CSFSchem.pdf.

Blumenthal DM, Bernard K, Bohnen J, Bohmer R. Addressing the leadership gap in medicine: residents’ need for systematic leadership development training. Acad Med. 2012;87:513–22.

Blumenthal DM, Bernard K, Fraser TN, Bohnen J, Zeidman J, Stone VE. Implementing a pilot leadership course for internal medicine residents: design considerations, participant impressions, and lessons learned. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:257.

Natesan S, Bailitz J, King A, Krzyzaniak SM, Kennedy SK, Kim AJ, et al. Clinical teaching: an evidence-based guide to best practices from the council of emergency medicine residency directors. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21:985–98.

Izatt S, Gray M, Dadiz R, French H. Development and implementation of a national neonatology flipped classroom curriculum. J Graduate Med Educ. 2019;11:335–6.

ONTPD Fellowship Directors Writing Group

Heather French7, Kris Reber8, Melissa Bauserman9, Misty Good10, Brittany Schwarz11, Allison Payne12, Melissa Carbajal13, Robert Angert1, Maria Gillam-Krakauer14, Jotishna Sharma15, Elizabeth Bonachea8, Jennifer Trzaski16, Lindsay Johnston17, Patricia Chess18,19, Rita Dadiz18, Josephine Enciso20, Mackenzie Frost7, Megan Gray21, Sara Kane22, Autumn Kiefer23, Kristen Leeman24, Sabrina Malik25, Patrick Myers26, Deirdre O’Reilly27, Taylor Sawyer21, M. Cody Smith23, Kate Stanley28, Margarita Vasquez29, Jennifer Wambach10

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Members of the ONTPD Fellowship Directors Writing Group are listed below Conclusion.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cicalese, E., Wraight, C.L., Falck, A.J. et al. Essentials of Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine fellowship: part 2 - clinical education and experience. J Perinatol 42, 410–415 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01042-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01042-5

- Springer Nature America, Inc.

This article is cited by

-

Development of a neonatal cardiac curriculum for neonatal-perinatal medicine fellowship training

Journal of Perinatology (2024)

-

Optimizing neonatal patient care begins with education: strategies to build comprehensive and effective NPM fellowship programs

Journal of Perinatology (2022)