Abstract

Based on data from national surveys, the prevalence of hypertension rests at 40–60% in Japan, the USA, and in European countries. This suggests there has been little progress in the prevention of hypertension in even high-income countries despite their well-functioning health systems. In particular, compared with the USA and European countries, the improvement in awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension has been relatively low in Japan. For example, the rates of hypertension awareness, treatment, and control were observed, respectively, in 60–70%, 50–60%, and 20–30% of Japanese compared with 80–90%, 70–80%, and 50–60% of US citizens in the years around 2015. The lower proportions in Japan might be explained by the slower progress in lowering the accepted thresholds for diagnosis of hypertension and initiation of treatment compared with Western countries; however, the underlying reasons for the differences warrant further study. The high prevalence (>40%) of uncontrolled hypertension in even high-income countries has major implications for the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Health policy and research on early control of high blood pressure at the individual and public health levels will contribute to decreases in the prevalence of hypertension. Furthermore, proactive treatment and strict adherence to intensified antihypertensive treatment guidelines will more effectively achieve targeted blood pressure levels. In this context, it is important to continue to carefully monitor and compare trends in hypertension across countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

High blood pressure (BP), known as hypertension, is a critical global health challenge because of its high prevalence and its role in the development of cardiovascular disease. Hypertension has been identified as the leading preventable risk factor for premature mortality and is ranked first as a cause of disability-adjusted life-years [1]. Randomized clinical trials have also demonstrated that antihypertensive treatment substantially reduces cardiovascular disease risk [2].

Current estimates of the global burden of hypertension and of the treatment and control of hypertension help us to understand these public health concerns. National health surveys have indicated that the prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension have all substantially improved in recent decades, especially in high-income countries with well-functioning health systems, such as Japan, the USA, and the European countries [3, 4]. Understanding of how these countries, with different lifestyle, health systems, and clinical guidelines, compare in terms of awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension can inform improvements and bring more effective and efficient prevention and management of hypertension.

This review of serial national surveys presents the trends in the prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension in Japan and compares these with similar trends in the USA and European countries, providing insights into the reasons for the differences.

Prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension in Japan

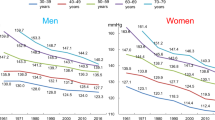

In Japan, levels of systolic BP steadily decreased during the years 1961–2016, by ≈10–20 mmHg in all age groups of men and women (Fig. 1) [5, 6]. The population-wide decline in systolic BP may be attributed to the screening and early identification of high BP or hypertension, lifestyle changes (including reduced salt intake), and improved hypertension treatment. Over the same period, the levels of diastolic BP also decreased, by ≈4–8 mmHg among all age groups of women but not among men aged 30–59 years (Fig. 2) [5, 6]. The recalcitrant diastolic BP trend in men aged 30–59 years may be explained by an increase in obesity, decrease in physical activity, and insufficient treatment of diastolic hypertension in this group [5,6,7].

Reprint from Hypertension Research (Hisamatsu et al. [6]) with permission, copyright © 2020, Springer Nature.

Reprint from Hypertension Research (Hisamatsu et al. [6]) with permission, copyright © 2020, Springer Nature.

The prevalence of hypertension, defined as BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg or use of antihypertensive medication, during the years 1980–2016 is presented in Fig. 3 [5, 6]. Over those 36 years, the prevalence decreased in women of all ages and in younger men aged 30–49 years. In contrast, this trend was not evident in men aged ≥50 years—in men aged 50–69 years, the prevalence of hypertension increased after 2000. In recent years, the prevalence of hypertension has remained high and has been found in over 60% of men aged ≥50 years and women aged ≥60 years. These trends suggest that the strong decline in BP levels until 2016—particularly in middle-aged and older groups of Japanese men and women, as shown in Fig. 1, can be mainly attributed to the development and expansion of medical treatment for hypertension that occurred during that time [6].

Reprint from Hypertension Research (Hisamatsu et al [6]) with permission, copyright © 2020, Springer Nature.

The hypertension treatment rate, defined as the proportion of hypertensive patients receiving antihypertensive medication, increased during the years 1980–2016 (Fig. 4) [5, 6], with no differences between the sexes. In 2016, in both sexes, >50% of hypertensive patients aged 60–69 years and >60% of those aged 70–79 years took antihypertensive medication.

Reprint from Hypertension Research (Hisamatsu et al. [6]) with permission, copyright © 2020, Springer Nature.

The trend in the hypertension control rate, defined as the proportion of treated hypertensive patients achieving BP < 140/90 mmHg, during the years 1980–2016 is presented in Fig. 5 [5, 6]. The hypertension control rate increased over the 36-year span, improving to ≈40% in both men and women by 2016. There was no difference in hypertension control among the age groups.

Reprint from Hypertension Research (Hisamatsu et al. [6]) with permission, copyright © 2020, Springer Nature.

It has been estimated that there were 43 million hypertensive individuals in Japan in 2017, of whom 31 million (73%) had poor control [6, 8]. Among those with poor control, 14 million (33%) were unaware of their hypertension and 4.5 million (11%) were aware of their condition but were not receiving treatment, while 12.5 million (29%) were aware and were receiving treatment but with poor control. Among all estimated hypertensive individuals, only 12 million (27%) were estimated to have maintained their BP below 140/90 mmHg.

These findings indicate that hypertension is a nationwide concern and suggest that, particularly in men, it is necessary to monitor BP regularly (e.g., with home BP measurement), to strive to maintain a “normal BP” from young adulthood, and to initiate lifestyle modification early to prevent hypertension later in life.

Comparison with the USA and European countries

The data on prevalence, treatment, and control of hypertension depend upon the definition of hypertension, the criteria for treatment, and the targeted BP (as determined by patient risk factors). The 2017 joint American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines on BP management newly defined hypertension as BP ≥ 130/80 mmHg, impacting both the eligibility for treatment and the criterion for control in the USA [9]. In contrast, the 2019 Japanese Society of Hypertension (JSH) Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension [8] and the 2018 European Guidelines for the Management of Arterial Hypertension [10] both retained the existing hypertension definition of BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg. Based on the definition of hypertension as BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg, the pooled data suggest that in 2000, ≈26% of the world’s adult population had hypertension [11]. In 2010, this estimate increased to ≈31% or roughly, 1.4 billion adults with hypertension [12].

Based on the latest national survey data from 12 high-income countries and a definition of hypertension as BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg or treatment with antihypertensive medication, the prevalence of hypertension in Japan was similar to or higher than that in the USA and most European countries in the years around 2015 (Fig. 6) [3]. For example, in Japan, the USA, and UK, respectively, the hypertension prevalence was 40%, 44%, and 36% in women and was 56%, 45%, and 40% in men. Notably, Japanese men had the second highest prevalence of hypertension among the high-income countries (Finland had the highest prevalence, while Canada and the UK had the lowest). Similarly, BP levels and hypertension prevalence were found to be higher in Japan compared with the USA in regional community-based studies of the two countries after 2000 [13]. Nevertheless, that hypertension prevalence remained at ≈40–60% around 2015 among high-income countries indicates there has been little progress in the prevention and management of hypertension in those countries despite their well-functioning health systems.

Results shown are crude (i.e., not age-standardized) to reflect the total burden of hypertension and its awareness, treatment, and control. The prevalence of hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg or the use of antihypertensive medication. Among participants with hypertension, the proportion of those who were aware of their condition (awareness), were treated (treatment), and whose hypertension was controlled (i.e., <140/90 mmHg) (control) were calculated. *The latest national survey in Ireland had data for people aged 50–79 years; data from an earlier survey in 2007 were used for people aged 40–49 years. †The question on awareness was not asked in 2015 in Japan; awareness data from 2010 were used. ‡The latest national survey in Spain had data for people aged 60–79 years; data from an earlier survey in 2009 were used for people aged 40–59 years. Modified from The Lancet (NCD Risk Factor Collaboration [3]), copyright © 2020, Elsevier.

Factors contributing to differences in prevalence

The difference in hypertension prevalence may be attributed to differences in lifestyle between Japan and the Western (USA and European) countries. Hypertension is a complex condition resulting from the interaction of multiple environmental and genetic factors (the rare occurrence of hypertension or age-related increases in systolic and mean BP in nonindustrialized societies confirms the important role of environmental exposure in defining hypertension risk) [14, 15]. High sodium intake has been linked to excess fluid intake, decreased arterial compliance, impaired renin–angiotensin activity, and reduced glomerular filtration rate, all of which exacerbate the hypertensive burden [16]. Dietary potassium promotes natriuresis and vasodilation [17], thereby lowering BP, and this suggests that low potassium intake also influences developing hypertension. The INTERMAP study in the 1990s showed that mean dietary intake of sodium measured by 24-h urine collection was higher in the Japanese than in the US and UK populations (urinary sodium was, respectively, 4278 mg/day, 3272 mg/day, and 2929 mg/day for women and 4843 mg/day, 4202 mg/day, and 3702 mg/day for men), while the opposite was true for potassium intake (urinary potassium was, respectively, 1891 mg/day, 1982 mg/day, and 2378 mg/day for women and was 1920 mg/day, 2512 mg/day, and 2912 mg/day for men); thus, the sodium–potassium ratio was higher in the Japanese than in the Western samples [18]. The differences in sodium intake between Japan and the Western countries endured in the 2010 s [19].

In general, Japanese men have a higher alcohol consumption than do Western men; [18] at the same time, almost half of Japanese have an atypical allele of the aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 gene, which has lesser capacity to catalyze acetaldehyde metabolism, producing an elevated BP after drinking [20]. Further, for the past 40 years, cigarette smoking has been more prevalent among Japanese men than among Western men [21], and given the effect of smoking on arterial stiffness and wave reflection, this too may have great detrimental effect on BP in Japanese men [22]. Notably, a lower prevalence of obesity [23] and a higher level of physical activity have historically been reported in Japan than in Western countries [24], although recently, both an increase in obesity and decease in physical activity have been observed with the increasingly “Westernized” Japanese lifestyle, especially in men, likely contributing to a higher burden of hypertension [6, 7].

Factors contributing to difference in awareness, treatment, and control

An analysis of national surveys from 12 high-income countries investigated levels of hypertension awareness, treatment, and control (according to the definition of BP < 140/90 mmHg) among individuals with hypertension (BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg or treated with antihypertensive medication) and found that in most countries, all of these have improved over the past 30 years, especially during the 1990s and early 2000s; [3] however, Japan ranked among the countries with the lowest levels (for all), while the USA ranked among the highest, in the years around 2015 (Figs. 6 and 7). For example, the rates of hypertension awareness, treatment, and control were observed, respectively, in 66%, 55%, and 29% of women and in 65%, 52%, and 24% of men in Japan, compared with 86%, 80%, and 54% of women and 79%, 70%, and 49% of men in the USA. A limitation of this review is that the thresholds for the diagnosis of hypertension and target BP level for the treatment of hypertension were both defined as 140/90 mmHg and thus they were not necessarily based on the hypertension guidelines of each country at that time.

Results shown are crude (i.e., not age-standardized) to reflect the total burden of hypertension and its awareness, treatment, and control. The prevalence of hypertension was defined as blood pressure ≥140/90 mmHg or the use of antihypertensive medication. Among participants with hypertension, the proportion of those who were aware of their condition (awareness), were treated (treatment), and whose hypertension was controlled (i.e., <140/90 mmHg) (control) were calculated. *The latest national survey in Ireland had data for people aged 50–79 years; data from an earlier survey in 2007 were used for people aged 40–49 years. †The question on awareness was not asked in 2015 in Japan; awareness data from 2010 were used. ‡The latest national survey in Spain had data for people aged 60–79 years; data from an earlier survey in 2009 were used for people aged 40–59 years. Modified from The Lancet (NCD Risk Factor Collaboration [3]), copyright © 2020, Elsevier.

The increases in awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension seen in the high-income countries in recent decades are probably the result of a combination of factors: [3] first, the introduction of simplified clinical guidelines for hypertension has been met with increasing uptake and compliance. Second, the introduction of lower thresholds for diagnosis and initiation of treatment have also contributed to higher rates of awareness, treatment, and control. Third, over time, newer drugs (e.g., renin-angiotensin system inhibitors and calcium-channel blockers) have become available and improved treatment efficacy and control (with fewer side-effects) over that seen with older generation agents, such as the thiazide diuretics. Finally, nationally implemented screening and preventive health programs may also have contributed to the observed improvements. Nonetheless, the overall high prevalence of uncontrolled hypertension (>40% in women and >50% in men in most countries) remains a major risk factor for future cardiovascular disease even in countries with well-functioning healthcare systems.

It is thus surprising that improvements in hypertension awareness, treatment, and control have been relatively low in Japan compared with in the USA and European countries, since Japan has a well-developed universal health insurance and preventive health system. It may be that the relatively slow Japanese adoption of guidelines with lower thresholds for diagnosis and initiation of treatment has played a role in this [25]. As late as 1990 Japan used a BP of 160/95 mmHg as the criterion for hypertension diagnosis and only in 2000 lowered the threshold to 140/90 mmHg [26], while the USA adopted the more stringent treatment criterion of 140/90 mmHg in 1993 [27]. Furthermore, the clinical guidelines also differ in other ways between Japan and the Western countries, for example, regarding the recommendations for patients with BP between 140/90 mmHg and 160/100 mmHg and few risk factors [3]. For patients in this hypertensive category, the 2019 JSH guidelines recommend lifestyle changes before initiating treatment [8], while the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines recommend immediate treatment [9]. As a result, physicians in Japan are less likely to proactively treat patients with BP between 140/90 mmHg and 160/100 mmHg than their counterparts in Western countries [28, 29]. In addition, physicians in Japan may be cautious about treating hypertension in older patients [4] who are generally more susceptible to adverse effects (e.g., hypotension, fall injury, and polypharmacy) from antihypertensive medication than are younger adults. In fact, the 2019 JSH guidelines propose the BP goal <140/90 mmHg for older patients aged ≥75 years and the BP goal <130/80 mmHg for those aged <75 years [8], whereas the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines dictate that BP < 130/80 mmHg should be targeted after the age of 65 years [9]. The term “clinical inertia” describes the failure of some physicians to recognize the need to intensify the antihypertensive treatment approach according to the guidelines and is a great barrier to the achievement of BP control in patients with hypertension [8]. A fundamental change in the attitudes of Japanese physicians may be needed to achieve levels of hypertension treatment and control similar to those in the Western countries [4]. Continuing study of the factors underlying the observed outcome differences is warranted, to improve the awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension.

Future plans for managing hypertension in Japan

If the prevalence and treatment and control rates observed in 2017 persist, there will be an estimated 44 million hypertensive patients in Japan by 2028 and among them, 32 million hypertensive patients with poor control. In an effort to conquer hypertension, the JSH has outlined a plan [30] that aims to reduce the number of hypertensive individuals with BP ≥ 140/90 mmHg by 7 million over the next decade, thereby extending healthy life expectancy in Japan. The number of hypertensive individuals with poor control will decrease by the targeted 7 million—from 31 million in 2017 to 24 million in 2028—if the following are achieved: (1) the hypertension prevalence decreases by 5 percentage points (the number of hypertensive individuals decreases by 3.2 million); (2) the hypertension treatment rate increases by 10 percentage points (the number of hypertensive individuals decreases by 1.9 million); and (3) the hypertension control rate (defined as BP < 140/90 mmHg among hypertensive individuals taking antihypertensive medication) increases by 10 percentage points (the number of hypertensive individuals decreases by 2.8 million) [6].

Conclusion

That the prevalence of hypertension hovers at 40–60% in Japan as well as in the USA and in European countries suggests there has been little progress in the prevention of hypertension, even in high-income countries with well-functioning health systems. Clearly, even in such countries, the high (>40%) prevalence of uncontrolled hypertension remains an important risk factor for substantial morbidity and mortality. Compared with the USA and the European countries, improvements in awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension have been relatively low in Japan, and the underlying reasons for the differences between countries warrant further study. Health policy and research on prevention and early control of high BP, at the individual and public health levels, can reduce the prevalence and adverse sequelae of hypertension. Furthermore, proactive treatment and strict adherence to intensified antihypertensive treatment guidelines can more effectively bring BP to the targeted level. In addition, it is important to continue to carefully monitor and compare trends in hypertension across countries.

References

GBD 2017 Risk Facotr Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1923–94.

Bundy JD, Li C, Stuchlik P, Bu X, Kelly TN, Mills KT, et al. Systolic blood pressure reduction and risk of cardiovascular disease and mortality: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2:775–81.

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration Long-term and recent trends in hypertension awareness, treatment, and control in 12 high-income countries: an analysis of 123 nationally representative surveys. Lancet. 2019;394:639–51.

Ikeda N, Sapienza D, Guerrero R, Aekplakorn W, Naghavi M, Mokdad AH, et al. Control of hypertension with medication: a comparative analysis of national surveys in 20 countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;92:10–19C.

Miura K Report for a Health and Labor Sciences Research Grant, Japan (Comprehensive research on life-style related diseases including cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus [H30-Jyunkankitou-Seisyu-Sitei-002]); 2019 (in Japanese).

Hisamatsu T, Segawa H, Kadota A, Ohkubo T, Arima H, Miura K. Epidemiology of hypertension in Japan: beyond the new 2019 Japanese guidelines. Hypertens Res. 2020;43:1344–51.

Nagai M, Ohkubo T, Murakami Y, Takashima N, Kadota A, Miyagawa N, et al. Secular trends of the impact of overweight and obesity on hypertension in Japan, 1980-2010. Hypertens Res. 2015;38:790–5.

Umemura S, Arima H, Arima S, Asayama K, Dohi Y, Hirooka Y, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension (JSH 2019). Hypertens Res. 2019;42:1235–481.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:e13–e115.

Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, Burnier M, et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology and the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2018;36:1953–2041.

Kearney PM, Whelton M, Reynolds K, Muntner P, Whelton PK, He J. Global burden of hypertension: analysis of worldwide data. Lancet. 2005;365:217–23.

Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, Reed JE, Kearney PM, Reynolds K, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation. 2016;134:441–50.

Hisamatsu T, Liu K, Chan C, Krefman AE, Fujiyoshi A, Budoff MJ, et al. Coronary artery calcium progression among the US and Japanese men. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:e008104.

Intersalt Cooperative Research Group. Intersalt: an international study of electrolyte excretion and blood pressure. Results for 24h urinary sodium and potassium excretion. BMJ. 1988;297:319–28.

Taddei S, Bruno R, Masi S, Solini A Epidemiology and pathophysiology of hypertension. In: Camm J, Lüscher TF, Maurer G, Serruys PW, editors. ESC CardioMed (3rd edition), Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2018. https://oxfordmedicine.com/view/10.1093/med/9780198784906.001.0001/med-9780198784906-chapter-563 (Access 1 Nov 2020).

Dickinson BD, Havas S. Council on science and public health, American Medical Association. Reducing the population burden of cardiovascular disease by reducing sodium intake: a report of the Council on Science and Public Health. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1460–8.

Smith SR, Klotman PE, Svetkey LP. Potassium chloride lowers blood pressure and causes natriuresis in older patients with hypertension. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1992;2:1302–9.

Zhou BF, Stamler J, Dennis B, Moag-Stahlberg A, Okuda N, Robertson C, et al. Nutrient intakes of middle-aged men and women in China, Japan, United Kingdom, and United States in the late 1990s: the INTERMAP study. J Hum Hypertens. 2003;17:623–30.

Powles J, Fahimi S, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Shi P, Ezzati M, et al. Global, regional and national sodium intakes in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis of 24 h urinary sodium excretion and dietary surveys worldwide. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003733.

Otani T, Iwasaki M, Yamamoto S, Sobue T, Hanaoka T, Inoue M, et al. Alcohol consumption, smoking, and subsequent risk of colorectal cancer in middle-aged and elderly Japanese men and women: Japan Public Health Center-based prospective study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2003;12:1492–500.

Ueshima H, Sekikawa A, Miura K, Turin TC, Takashima N, Kita Y, et al. Cardiovascular disease and risk factors in Asia: a selected review. Circulation. 2008;118:2702–9.

Virdis A, Giannarelli C, Neves MF, Taddei S, Ghiadoni L. Cigarette smoking and hypertension. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16:2518–25.

GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators, Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, Sur P, Estep K, et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:13–27.

Guthold R, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Bull FC. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1.9 million participants. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e1077–e1086.

Sekikawa A, Hayakawa T. Prevalence of hypertension, its awareness and control in adult population in Japan. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18:911–2.

Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines Subcommittee for the Management of Hypertension. Guidelines for the management of hypertension for general practitioners. Hypertens Res. 2001;24:613–34.

The fifth report of the Joint National Committee on Detection. Evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure (JNC V). Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:154–83.

Ikeda N, Hasegawa T, Hasegawa T, Saito I, Saruta T. Awareness of the Japanese Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension (JSH 2000) and compliance to its recommendations: surveys in 2000 and 2004. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20:263–6.

Hyman DJ, Pavlik VN. Self-reported hypertension treatment practices among primary care physicians: blood pressure thresholds, drug choices, and the role of guidelines and evidence-based medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2281–6.

Node K, Kishi T, Tanaka A, Itoh H, Rakugi H, Ohya Y, et al. The Japanese Society of Hypertension-Digest of plan for the future. Hypertens Res. 2018;41:989–90.

Acknowledgements

We thank Eleanor Scharf, MSc(A), from Edanz Group (https://en-author-services.edanzgroup.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

The NIPPON DATA80/90/2010 were supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare under the auspices of the Japanese Association for Cerebro-cardiovascular Disease Control; a Research Grant for Cardiovascular Diseases (7A-2) from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; and a Health and Labour Sciences Research Grant, Japan (Comprehensive Research on Aging and Health [H11-Chouju-046, H14-Chouju-003, H17-Chouju-012, H19-Chouju-Ippan-014] and Comprehensive Research on Life-Style Related Diseases including Cardiovascular Diseases and Diabetes Mellitus [H22-Junkankitou-Seishuu-Sitei-017, H25- Junkankitou-Seishuu-Sitei-022, H30-Junkankitou-Seishuu-Sitei-002]).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hisamatsu, T., Miura, K. Epidemiology and control of hypertension in Japan: a comparison with Western countries. J Hum Hypertens 38, 469–476 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-021-00534-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-021-00534-3

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

The trends of antihypertensive drug prescription based on the Japanese national data throughout the COVID-19 pandemic period

Hypertension Research (2024)

-

High blood pressure in childhood and adolescence

Hypertension Research (2024)

-

High blood pressure and colorectal cancer mortality in a 29-year follow-up of the Japanese general population: NIPPON DATA80

Hypertension Research (2024)

-

Risk factors for unfavourable outcomes after shunt surgery in patients with idiopathic normal-pressure hydrocephalus

Scientific Reports (2022)