Abstract

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is the main secondary form associated with resistant hypertension (RH), but it is largely underdiagnosed and consequently undertreated in clinical practice. The Berlin questionnaire (BQ) is a useful tool among general population, but seems to not perform well among patients with RH. Recently, NoSAS score was validated in a large population, however, has not been tested in the cardiovascular scenario. Thus, we aimed to compare BQ versus the NoSAS score as screening tools for OSA in RH. In the present study, patients with confirmed diagnosis of RH were invited to perform polysomnography. OSA was diagnosed by an apnoea-hypopnoea index (AHI) ≥15 events/h. BQ and NoSAS were applied in a blinded way. We calculated the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and area under the curve (AUC) of the two sleep questionnaires to detect OSA in RH. The frequency of OSA was 64%. The BQ presented a better sensitivity (91 vs. 72%) and higher values of NPV (67 vs. 54%) than NoSAS score. In contrast, the NoSAS score had higher specificity for excluding OSA (58 vs. 33%) and higher PPV (75 vs. 70%). Compared to the BQ, NoSAS score had a better AUC (0.55 vs. 0.64) but these values are in the fail to poor accuracy range. In conclusion, both BQ and NoSAS score had low accuracy for detecting OSA in RH. Considering the high frequency of OSA, objective sleep study may be considered in these patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Resistant hypertension (RH) is characterised by the blood pressure (BP) above target levels despite the concomitant treatment of three antihypertensive drugs of different classes, at optimal and tolerated doses, including a diuretic, or the need for more than three medications to achieve goal BP [1]. This subtype of hypertension is associated to an increase risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [2].

It is well known that secondary forms of hypertension are particularly frequent in RH and may contribute to BP resistance. Among them, obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) has been recently pointed the most common secondary cause associated with RH [3]. Indeed, its prevalence varies from 64 to 85% of these patients [1, 3,4,5]. In contrast to overall modest effects of OSA treatment on BP, the use of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device in patients with OSA and RH was able to significantly reduce BP by >5 mmHg [6, 7]. Therefore, identifying and treating OSA may be helpful to improve prognosis in these patients [6, 7].

Polysomnography is the recognised gold standard for OSA diagnosis [8]. However, considering its high cost and difficult availability of clinical practice, polysomnography is a difficult procedure to perform as a routine for screening patients with OSA. Thus, many screening tools were developed to identify patients at high risk for OSA, including the Berlin questionnaire (BQ). This tool is widely used in the general population [9]. However, in patients with RH, one study showed that BQ did not perform well in identifying OSA [10].

Recently, the NoSAS score, a new clinical screening toll for OSA, which is based of simple clinical data was available [11]. The original article validated NoSAS in two distinct large general populations showing a better performance than BQ [11]. It is worth highlighting that the NoSAS score is less influenced by subjective and unspecific questions such as fatigue after sleep used in BQ [11], making it a possible helpful tool for screening OSA in the cardiovascular scenario as well. Thus, the aim of the present study was to compare de BQ versus the NoSAS score as screening tools for OSA in patients with RH. We made the hypothesis that NoSAS score, but not BQ, has good accuracy in detecting significant OSA in consecutive patients with RH.

Methods

Study design and participants

From a total of 125 consecutive patients with true RH recruited from two tertiary hospitals in Brazil after a rigorous protocol including ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (please see details in our previous work) [3], 119 patients with complete data were included in the present study. All these patients had demographic (sex, age, body mass index, neck and waist circumferences), clinical data (systolic and diastolic BP and number of antihypertensive drugs used), sleep questionnaires and full polysomnography. No single patients were under specific treatments for OSA. The ethic committee approved the protocol and written informed consent was acquired from all participants.

Berlin questionnaire

The BQ is a tool for screening OSA based on questions in three categories regarding: 1) snoring and cessation of breathing; 2) tiredness and fatigue after sleep; 3) the presence of obesity (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2) or hypertension. High risk of OSA is defined when ≥2 symptom categories are positive [9].

NoSAS score

The NoSAS score comprises questions easily accessed in the clinical routine (neck circumference, obesity, snoring, age and sex). The score ranges from 0 to 17 points. This tool attributed 4 points for a neck circumference of >40 cm, 3 points for a BMI of 25 to <30 kg/m2, 5 points for a BMI of ≥30 kg/m2, 2 points for snoring, 4 points for being older than 55 years of age, and 2 points for male gender. A score above or equal to 8 points identify individuals at risk of clinically significant sleep-disordered breathing [11]. Of note, this tool was only recently available in clinical practice [11]. Therefore, the timing of the administration of BQ and NoSAS score were different. However, in order to avoid potential bias, we took the following procedures: 1) to fill out the NoSAS score, we used the same clinical data measured at the time we applied the BQ and polysomnography; 2) a same researcher (S.Q.C.G.), not involved in the preliminary study, performed the NoSAS score with no access to BQ and polysomnography data.

Polysomnography

All patients underwent a full-night polysomnography (EMBLA; Flagra hf. Medical Devices), as previously described [12]. Apnoeas and hypopnoea events were, respectively, defined as ≥90% cessation of airflow at least 10 s and a 30% reduction in respiratory signals for at least 10 s, followed by a 3% desaturation and/or arousal. The apnoea-hypopnoea index (AHI) was obtained by dividing the total number of apnoeas and hypopnoeas by total sleep time. OSA was defined by an AHI was ≥15 events per hour of sleep. This conservative cutoff was adopted because of the lack of significant cardiovascular impact of mild OSA as recently reviewed by an American Thoracic Society statement [13].

Statistical analysis

Statistica 12 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, USA) and GraphPad Prism 7.0 (CA, USA) were used for performing statistical analyses and figures. Student’s t test was used to compare the demographic and clinical data between the patients with or without OSA. Quantitative variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of the instruments to detect OSA in patients with RH were calculated and exhibited as percentage. We also calculated area under the curve (AUC) from both questionnaires using different AHI cut-offs. The accuracy was based in the values of AUC. The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 119 patients with RH (43% men; 57% women) were evaluated. The frequency of OSA was 64%. The basic characteristics of patients with RH according to OSA status are displayed in Table 1. As expected, patients with OSA were older, had higher frequency of males, higher BMI, neck and waist circumference. No differences were observed in the office BP and number of anti-hypertensive drugs. As expected, patients with OSA had a higher frequency of high risk for OSA either by BQ as NoSAS score, higher AHI and hypoxemic parameters during sleep than patients without OSA.

According to Fig. 1a, we observed that the BQ presented a better sensitivity than the NoSAS score in identifying OSA in patients with RH. However, the NoSAS score was more specific. NoSAS score presented higher values of PPV for OSA (Fig. 1b). On the other hand, BQ presented higher values of NPV (Fig. 1c).

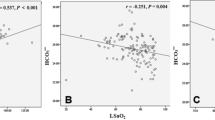

The Fig. 2 reported the performance of BQ and NoSAS score using AHI cut-offs: ≥5 (comprising mild to severe OSA), the adopted criterion of ≥15 (including only moderate to severe OSA) and ≥30 events/hour of sleep (limited to severe OSA). NoSAS score had better AUC for the most severe forms of OSA compared to BQ but the values translate into a low accuracy for detecting OSA when we used both questionnaires.

Area under the curve for NoSAS score and Berlin Questionnaire (BQ) according to the most used apnoea-hypopnoea index (AHI) cut-offs: ≥5 (mild to severe OSA), ≥15 (moderate to severe OSA) and ≥30 events/h of sleep (severe OSA) in patients with resistant hypertension (RH). For AHI ≥ 5-BQ: AUC 0.57 (95% CI 0.49–0.65); NoSAS score: AUC 0.53 (95% CI 0.46–0.61). For AHI ≥ 15–BQ: AUC: 0.55 (95% CI 0.45–0.64); NoSAS score: AUC 0.64 (95% CI 0.55–0.73). For AHI ≥ 30–BQ: AUC 0.51 (95% CI 0.38–0.64); NoSAS score: AUC: 0.66 (95% CI 0.53–0.78). CI confidence interval

Discussion

This is the first study to compare the NoSAS score and BQ performance for screening OSA in consecutive patients with RH. Confirming previous literature [10], the BQ presented low accuracy, although had higher values of sensitivity (91%) and NPV (67%) than NoSAS score. Overall, the NoSAS score had higher accuracy to detect OSA than BQ, especially for most severe forms of OSA. However, the observed results suggest that both instruments are not useful for screening OSA in RH. Taken together, considering the high frequency of OSA in patients with RH and the potential impact of OSA on this subset of patients, the lack of ideal questionnaire for screening OSA underscore the need for objective sleep study in the presence of RH, or even a portable monitoring (polygraph), which is accessible and potentially a cost-effective alternative.

It is well known that BQ has been one of the most popular screening methods for OSA but its utility has been recently questioned specially in patients with cardiovascular disease [14]. Beyond subjective questions related to tiredness and fatigue after sleep, the other domain of BQ is related to high BP, making this questionnaire particularly susceptible to overestimate OSA in patients with hypertension. Corroborating our data, Margallo et al. [10] observed low accuracy of BQ in detecting OSA in RH, in addition to moderate sensitivity (69%) and poor specificity (40%). Of note, there were no improve the performance the BQ when the researchers evaluated their capacity associated with clinical variables [10]. Specifically, the authors performed a modified BQ (considering only obesity in category 3). Despite increase of specificity and positive likelihood ratio, kappa coefficients remained with a very low agreement [10]. Thus, consistent evidence from literature does not support the use of BQ as a useful screening tool for OSA in patients with RH.

The recent development of NoSAS score brought significant attention in the literature not only by having a good performance for screening OSA in the different populations including European, Brazilian and in a multiethnic Asian cohort [11, 15]. Importantly, the NoSAS score is very easy to apply and focused on more objective questions. However, the NoSAS score has not been tested in patients with cardiovascular diseases. Contrary to our hypothesis, the poor performance of NoSAS score observed in our study call to the attention that OSA may have distinct phenotypes in patients with cardiovascular disease. The precise reasons for poor performance of NoSAS score in patients with RH are not entirely clear. Overweight (3 points in NoSAS score) and obesity (5 points in NoSAS score) are very common in patients with RH [16] and may not be entirely helpful in discriminating patients with and without OSA. Of note, the mean BMI in the no OSA group was 29 ± 4 Kg/m2. Moreover, contrary to the traditional impact of male gender on OSA, the percentage of women in the RH scenario is high, especially in those with refractory hypertension [16]. In this context, the lack of typical phenotypes in parallel to the lack of feasible and trustable tools may partially explain why OSA is largely underdiagnosed in RH and consequently undertreated in clinical practice [17].

Our study has strengths and limitations. We used standard polysomnography, which is considered the gold standard method for diagnosing OSA. We also studied consecutive patients with true RH after a stringent protocol. The following limitation should be acknowledged: because NoSAS score was only recently developed and validated [11], the timing of the administration of Berlin and NoSAS score was different. However, we used the same clinical data measured at the time we applied the BQ and polysomnography and a same researcher performed the NoSAS score with no access to BQ and polysomnography data.

In conclusion, although the NoSAS score performed better than BQ, both tools are still in the low accuracy range for detecting OSA in RH. Considering the high frequency of OSA and no ideal tool for screening, objective sleep study may be considered for these patients.

Summary Table

What is known about topic?

-

Previous studies showed that Obstructive Sleep Apnoea (OSA) is common in patients with resistant hypertension (RH) but underdiagnosed in clinical practice in part by the frequent lack of symptoms such as daytime somnolence.

-

Berlin questionnaire is a validated screening method for OSA in the general population but used subjective questions and seems to have low performance in patients with RH.

-

NoSAS score is an objective new clinical screening toll for OSA in the general population, being validated in large populations of Europe, Brazil and Asia.

What this study adds?

-

Using polysomnograhy as a gold standard method for diagnosing OSA and careful selection of consecutive cases true RH, we found that NoSAS escore has higher area under the curve (AUC) than Berlin questionnaire but both tools are in the low accuracy range for detecting OSA in patients with RH.

-

Considering the high frequency of OSA and the potential benefits of OSA treatment in RH, these results underscore the concept that objective sleep study may be considered in these patients.

References

Calhoun DA, Jones D, Textor S, Goff DC, Murphy TP, Toto RD, et al. American Heart Association Professional Education Committee. Resistant hypertension: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2008;117:e510–26.

Daugherty SL, Powers JD, Magid DJ, Tavel HM, Masoudi FA, Margolis KL, et al. Incidence and prognosis of resistant hypertension in hypertensive patients. Circulation. 2012;125:1635–42.

Pedrosa RP, Drager LF, Gonzaga CC, Sousa MG, de Paula LK, Amaro AC, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea: the most common secondary cause of hypertension associated with resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;58:811–7.

Logan AG, Perlikowski SM, Mente A, Tisler A, Tkacova R, Niroumand M, et al. High prevalence of unrecognized sleep apnoea in drug-resistant hypertension. J Hypertens. 2001;19:2271–7.

Muxfeldt ES, Margallo VS, Guimarães GM, Salles GF. Prevalence and associated factors of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with resistant hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:1069–78.

Pedrosa RP, Drager LF, de Paula LK, Amaro AC, Bortolotto LA, Lorenzi-Filho G. Effects of OSA treatment on BP in patients with resistant hypertension: a randomized trial. Chest. 2013;144:1487–94.

Liu L, Cao Q, Guo Z, Dai Q. Continuous positive airway pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and resistant hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Hypertens. 2016;18:153–8.

Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ Jr, Friedman N, Malhotra A, Patil SP, et al. Adult obstructive sleep apnea task force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:263–76.

Netzer NC, Stoohs RA, Netzer CM, Clark K, Strohl KP. Using the Berlin Questionnaire to identify patients at risk for the sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:485–91.

Margallo VS, Muxfeldt ES, Guimaraes GM, Salles GF. Diagnostic accuracy of the Berlin questionnaire in detecting obstructive sleep apnea in patients with resistant hypertension. J Hypertens. 2014;32:2030–6.

Marti-Soler H, Hirotsu C, Marques-Vidal P, Vollenweider P, Waeber G, Preisig M, et al. The NoSAS score forscreening of sleep-disordered breathing: a derivation and validation study. Lancet Resp Med. 2016;4:742–8.

Drager LF, Bortolotto LA, Lorenzi MC, Figueiredo AC, Krieger EM, Lorenzi-Filho G. Early signs of atherosclerosis in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:613–8.

Chowdhuri S, Quan SF, Almeida F, Ayappa I, Batool-Anwar S, Budhiraja R, et al. ATS AdHoc Committee on Mild Obstructive Sleep Apnea. An Official American Thoracic Society Research Statement: Impact of Mild Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults. Am J Resp. Crit Care Med. 2016;193:e37–54.

Sert Kuniyoshi FH, Zellmer MR, Calvin AD, Lopez-Jimenez F, Albuquerque FN, van der Walt C, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the Berlin Questionnaire in detecting sleep-disordered breathing in patients with a recent myocardial infarction. Chest. 2011;140:1192–7.

Tan A, Hong Y, Tan LW, van Dam RM, Cheung YY, Lee CH. Validation of NoSAS score for screening of sleep-disordered breathing in a multiethnic Asian population. Sleep Breath. 2017;21:1033–8.

Dudenbostel T, Siddiqui M, Oparil S, Calhoun DA. Refractory hypertension: a novel phenotype of antihypertensive treatment failure. Hypertension. 2016;67:1085–92.

Costa LE, Uchôa CH, Harmon RR, Bortolotto LA, Lorenzi-Filho G, Drager LF. Potential underdiagnosis of obstructive sleep apnoea in the cardiology outpatient setting. Heart. 2015;101:1288–92.

Acknowledgements

We thank Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo and Fundação Zerbini for funding research support. We also thank Altay Alves Lino de Souza for statistical advice.

Funding

FAPESP (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Giampá, S.Q.C., Pedrosa, R.P., Gonzaga, C.C. et al. Performance of NoSAS score versus Berlin questionnaire for screening obstructive sleep apnoea in patients with resistant hypertension. J Hum Hypertens 32, 518–523 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-018-0072-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-018-0072-z

- Springer Nature Limited

We’re sorry, something doesn't seem to be working properly.

Please try refreshing the page. If that doesn't work, please contact support so we can address the problem.