Abstract

Background

Obesity in Childhood is a significant public health issue, which requires both a preventative and treatment approach. International guidelines continue to recommend family-focused, multicomponent, childhood weight management programmes and many studies have investigated their effectiveness, however, findings have been mixed and primarily based on weight. Thus, the aim of this review was to assess the effectiveness of group-based parent-only interventions on a broad range of child health-related outcomes and to investigate the factors associated with intervention outcomes.

Methods

An electronic database search was conducted using CINAHL, Medline, PsychINFO, Embase and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: 522 articles were identified for full text review and 15 studies were selected. The quality of studies were appraised and data were synthesised according to the review aims.

Results

Parent-only group interventions are effective in changing children’s weight status, as well as other outcomes such as health behaviours and self-esteem, although these were reported inconsistently. Parent-only interventions were generally found to be similar to parent-child interventions, and minimal contact interventions but better than a waiting list control. Factors found to be associated with treatment outcomes, included session attendance, the child’s age and weight at baseline, socioeconomic status of families and modification to the home food environment. The methodological quality of the studies included in the review was low, with only six studies rated to be methodologically adequate.

Conclusions

Parent-only interventions may be an effective treatment for improving the health status of children and their families, particularly when compared with waitlist controls. However, results need to be interpreted with caution due to the low quality of the studies and the high rates of non-completion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Children and adolescents who are overweight or obese face social, emotional and physical challenges [1, 2] and evidence shows that childhood obesity can continue into adulthood [3,4,5]. Once established, obesity is difficult to reverse [6, 7]. Thus, while treatment of childhood overweight is clearly important, prevention is also crucial [8].

Family-based interventions are considered the current best practice in the treatment of childhood obesity [9, 10]. However, interventions that involve the whole family can be costly, in particular when not running at full capacity [11]. Thus, parent-focused interventions that do not include the child have become increasingly popular. Three recent reviews [12,13,14] reported parent-only interventions to be as effective as family-focused interventions in the treatment of childhood overweight/obesity.

However, several questions remain unanswered. Firstly, systematic reviews evaluating the effectiveness of parent-only weight management interventions for children have primarily included children who are overweight and/or obese [14] and have not included preventative interventions or those at risk of developing overweight. Secondly, weight outcomes (e.g. BMI, weight for height, weight loss, body fat content, skinfold thickness etc) are often chosen as the exclusive or primary outcome measure [15]. Factors that affect weight, for example, measures of self-efficacy, self-esteem and wellbeing, and changes in diet and physical activity, and time spent being sedentary are either excluded or are listed as secondary outcomes. Given the complex nature of obesity, these factors are important to target and monitor. Furthermore, weight status us just one measure of health and, given that obesity is difficult to reverse once established, it is imperative that a broad and inclusive overview of health is considered. A report commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) on lifestyle weight management programmes for children and young people also highlighted that most programs are short (8–12 weeks), making substantial weight change unlikely [16]. Moreover, the report identified unrealistic outcome measures as a barrier to providers working effectively with commissioners. As such, it is essential to report health behaviour change as a result of weight management programmes. Such programmes have the potential to help improve how children and adolescents see themselves, which may, in turn, enhance their future wellbeing (even if weight loss is not apparent in the short term) [17].

Thirdly, while previous reviews of weight-management interventions for parents of children who are overweight/obese have tended to pay particular attention to group-based intervention formats [12,13,14] many studies included in their reviews employ a mixed format, supplementing group sessions with shortened individual meetings. While the inclusion of an individual component in a group-based intervention has been shown to produce optimal outcomes [18], it also requires considerably more resources in comparison to group treatment alone and fails to tell us about the efficacy of purely group-based interventions.

Thus, the aim of this review is to critically examine the literature on the effectiveness of parent-only, group-based interventions, without an individual component, with a specific focus on children’s wider health and health-related behaviours, as well as children of non-obese status. In addition, identifying specific characteristics of the programme and participants that may contribute to the outcomes of the programme may help to enhance our understanding of what works for whom and why.

The aims of this review are:

-

1.

To assess the effectiveness of purely group-based parent-only interventions for children of all weight status, in relation to changes in health behaviours and psychological wellbeing, as well as more traditional measures of weight/BMI.

-

2.

Where studies report such factors, to find out the socio-demographic characteristics, process indicators and/or contextual factors that might contribute to the successful outcomes of such interventions.

Methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The current review was completed in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis [PRISMA; [19]. Eligibility criteria are reported in accordance with the PICOS framework [20]. See Table 1 for inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Search strategy

Five electronic databases were searched: Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), MEDLINE (Ovid), PsychINFO (Ovid), Embase (Ovid) and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. In addition, reference lists of all retrieved articles and review articles were screened for potentially eligible articles. Publication year was not restricted and the search was run in July 2022. In order to avoid publication bias, both published papers, and unpublished theses were included in the search. Search strategy consisted of search strings composed of terms targeting the following five concepts: (1) family-based (2) intervention (3) children (4) weight-management and (5) Effectiveness. A combination of index and mesh terms were used according to the requirements of each database. An example search strategy used in PsychiInfo is presented in Table 2.

Analysis plan

Studies were methodologically heterogeneous (including different sample sizes, intervention components, outcome measures and comparator groups) and clinically heterogeneous (including participants of different ethnicities, duration of interventions and follow-ups). Data were therefore analysed using a narrative rather than meta-analytic approach. This decision is in line with recommendations by the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review group [21].

Data extraction

Data were extracted from eligible studies by the first author using a data extraction form developed specifically to capture the effectiveness of interventions and the factors associated with change. Data were extracted and tabulated regarding key participant and intervention characteristics, outcome measures employed, factors associated with change post intervention and a summary of the main findings in relation to primary outcomes. A second reviewer independently extracted data from 20% of selected studies and the inter-rater agreement rate was 95%.

Quality appraisal

The Clinical Tool for Assessment of Methodology [CTAM; [22] was used to rate the methodological quality of the identified studies. It consists of six subscales. Scores range from 0–100, with scores of 65 or above representing adequate methodology [23]. See Appendix A in the Appendices for the CTAM Rating Guidelines.

Results

Database search

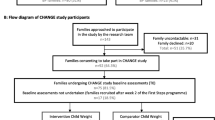

Database searches identified 7357 records, of which 6072 remained after the removal of duplicates. After screening of titles and abstracts, 5550 studies were excluded and 522 were identified as possibly relevant. Fifteen studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the review [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37], (Fig. 1). At this stage, the reference lists of identified papers were searched manually to identify possible omitted studies. No studies that met the inclusion criteria were identified.

Overview of included studies

All selected studies were published in English in peer-reviewed journals. All fifteen studies utilised pre and post data and were randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Fourteen RCT’s were parallel comparisons with individual randomization. In most trials, the unit of randomization was the family (parent and child), however, study authors analysed the children and parents for respective outcomes separately. One RCT was a cluster RCT, where the 4-H Youth Development club was the unit of randomisation. Thirteen RCTs were superiority trials, one had a non-inferiority study design, and one an equivalence study design. Four RCTs had three comparisons; the remaining trials had two comparison groups. For a detailed description of general study and intervention characteristics, see Table 3.

General study characteristics

Seven trials were undertaken in the USA, three in Israel and one each from Iran, the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland and Sweden.

A total of 1490 parents of children and adolescents participated in fifteen studies in this review. The number of participants included in the fifteen trials ranged between 38 and 247.

Nine trials reported the sex of the participating parent. Of these, two included mothers only in their interventions. Of the other seven, the majority were mothers (n = 535, 79%). The mean age of parents was reported in twelve trials and ranged between 38 and 43 years. All trials included parents of children aged between 4 and 14 years, the majority of which did not include children above 11 years of age. The mean age of children was reported in all fifteen trials and ranged from 5 to 11 years.

Thirteen trials included parents of children that were either overweight or obese, while two trials also included children categorised as normal weight. Diagnostic criteria differed between trials, with eight trials using BMI above the 85th percentile as the cut-off and one trial using the 95th percentile. Others used parental-report of weight status, a specified BMI cut-off or the proportion of BMI above expected BMI.

Only seven trials reported ethnicity of either the parent or their child and, in all trials except two [24, 32], there was a high proportion of parents or children categorised as white (between 76% and 100%). Nine trials reported socioeconomic indices of the parents. Each used a different indicator of socioeconomic status.

Intervention characteristics

Intervention characteristics are presented in Table 3. Eleven trials reported the settings for the interventions. Three took place in a community setting, two in a university, one in a school and another in a medical centre. The remaining four trials were a combination of settings including outpatient, university, or primary care.

Intervention length varied greatly over the reviewed studies, ranging from 10 weeks to 12 months. Session duration also ranged from 1 to 4 h. All but one study followed participants up beyond the timing of the end of the intervention [33] and thirteen studies reported the duration of follow-up. Two trials reported three-month follow-up and eight reported six-month follow-up. In two trials, participants were followed up one year [29] and two years [37] post intervention. In another study [36] follow-up occurred at two time points - six and twelve months post intervention.

The interventions in the included trials predominantly focused on nutritional, physical activity and behavioural components. Two studies employed a Cognitive Behavioural Treatment (CBT) model and one utilised an intervention based on Social Cognitive Theory. Eight studies included parenting components, such as parental modelling and enhancing parental skills and three integrated body image topics into their interventions.

All studies reported details of personnel delivering interventions. Interventionists were dieticians in three studies, doctoral psychologists or therapists in four studies and, in two studies, a dietician and psychologist led intervention sessions. Both studies that employed CBT interventions were led by CBT therapists [31, 34]. In the remaining three studies, interventionists were programme agents [26, 30] or the study author led sessions [27].

Quality appraisal

A summary of CTAM scores is presented in Table 4 below. Six trials had a CTAM score over 65, which is considered to be adequate [22].

Effects of Interventions

Included trials had different durations of interventions and follow-up (see Table 3). Both are discussed below.

BMI and body weight

All but one trial [28] reported BMI variables at the end of the intervention. BMI z-scores were reported in nine trials [24,25,26, 29, 30, 34,35,36], BMI percentiles in two trials [31, 32] and in the remaining trials, BMI – Standard Deviation Score [37] or BMI [27] were presented. One study [33] is not included here as it relied on parental-report. Results should be interpreted cautiously due to the low quality of most of the included trials and the differences between the interventions and comparators. See Table 5 for summary of results.

Effect of parent-only interventions on BMI and body weight

In all but one trial [27], children of the parent-only groups experienced a reduction in the degree of overweight from baseline to post intervention. Esfarjani et al. [27] found a significant increase in children’s BMI immediately post intervention and at follow-up, although the increase was lower in the parent-only group compared to the minimal contact control group. In the studies reporting a reduction in weight, the response over time varied by study. Six studies found that reductions continued to either decrease at follow-up [25, 28, 29, 34, 35] or were maintained [35] and two studies found gains following treatment not maintained at 6 month follow-up [26, 30]. Few trials reported outcomes over a relatively long period of follow-up (e.g. over two years).

As there was substantial heterogeneity between the studies regarding the comparison groups employed (e.g. parent-child; child-only, waitlist control; minimal contact control), their effectiveness as compared to parent-only interventions on measures of BMI variables and weight will be reported separately.

Parent-only interventions verses parent-child and child-only interventions

Six trials reported comparisons of a parent-only intervention with either a parent-child or child-only intervention [25, 28,29,30, 32, 37]. The two superiority trials by Golan et al. showed significantly greater reductions in the degree of overweight from the parent-only groups in comparison with the parent-child [29] and child-only [28] groups immediately post-intervention and at 6 and 12 months follow-up, respectively. The remaining four trials found no significant between-group differences for weight outcomes. These four studies encompassed different study designs and measures of weight but all showed no difference between parent-only and parent-child groups. All trials had either high rates of non-completion across groups or differential non-completion rates between study groups and, therefore, these results need to be interpreted with caution.

Parent-only interventions verses waitlist or minimal contact control interventions

Six trials compared parent-only interventions with either a waitlist [30, 31] or minimal contact control group [26, 27, 32, 36]. In both waitlist control trials, a treatment effect in favour of the parent-only interventions was found at post-treatment and follow-up. Again these results should be interpreted with caution. Jansen et al. [31] was at a high risk of bias owing to nine families originally allocated to the waitlist control group being included in the data set for the parent-only intervention, and Janicke et al [30] had a high risk of attrition bias as they did not report adequate means (e.g. intention-to-treat analysis) to address their high levels of drop-out in their analysis. Of the four trials that used a minimal contact control group as their comparator, two found no difference between groups at post-intervention and follow-up [26, 27] while two found significantly greater reductions in BMI scores in the parent-only group [32, 36].

Parent-only interventions versus parent-only interventions

Finally, three trials reported comparisons of two different parent-only interventions [24, 35] with mixed results. Raynor et al. [35] reported two trials in one publication and each trial had three arms, a standard arm that was a growth monitoring intervention and two additional parent-only arms. Results indicated that in both trials, all three interventions showed significant improvements in child weight status from baseline to post-intervention and follow-up, with no differences among interventions. In the Anderson et al. [24] study, the only difference between the two parent-only interventions was that the ‘intervention’ group parents received paid time off work to attend the programme while the other group did not. Those in the paid group experienced a decrease in their BMI z score at follow-up, while children in the comparison group experienced an increase in BMIz score from baseline to follow-up. It should be noted that, across all studies, the two trials by Raynor et al. [35] were rated the highest on the CTAM in terms of their methodological quality, while the other study [24] did not achieve a score above 65 on the CTAM, which suggests inadequate methodology.

Behaviour change

All but two studies [26, 32] measured changes in children’s behaviour (e.g. eating style, energy consumption, physical activity, problem behaviour, etc) at the end of the intervention.

Energy intake, home food environment and eating behaviours

Change in children’s energy intake was reported by four studies [25, 30, 35]. All four studies found that parent-only interventions resulted in significant decreases in children’s caloric intake from baseline to post-intervention and follow-up. In terms of the between-groups differences, findings were equivocal. Three of the four studies reported no significant between-group differences [30, 35]. One study reported in favour of a greater reduction of calories in the parent-child group [25].

Change in the family home food environment was reported by only two studies [24, 29]. Both studies reported a significant decrease in the obesogenic home food environment in the parent-only intervention. In both studies, there were significant between-group differences in favour of the parent-only group (versus parent-child and parent-only without worksite support; [24, 29].

Change in children’s eating behaviours (regularity and the consumption of unhealthy/healthy food items) was reported by seven studies with equivocal findings. A significant increase in children’s consumption of healthy foods and a decrease in consumption of unhealthy foods in the parent-only group was reported in three studies [27, 35], while three studies found no significant decrease in children’s consumption of unhealthy food items from pre to post-intervention [31, 36, 37]. Parents in the parent-only group in the study by Moens et al. [33] reported a significant decrease in their child’s external eating,(i.e. tendency to eat in response to external cues, such as sight or smell of food), however, this was not corroborated by child reports.

Physical activity

Changes in children’s physical activity levels were reported by seven studies. Two studies were excluded due to use of unvalidated measures [27, 33]. Findings from the remaining five studies were mixed. Three found a significant increase in children’s physical activity levels at 5 and 11 months [25], 26 weeks [29] and at 3 months [37]. However, for Yackobovitch et al. [37] this increase disappeared by the 2-year follow-up. Two studies reported no significant increase in children’s physical activity levels [31, 35]. No between group differences were found across studies [25, 28, 29, 37]. Measures of physical activity differed across studies (see Table 5).

Behaviour problems

One study reported improvements in overall behaviour that were maintained at follow-up as measured by the German version of the Child Behaviour CheckList (CBCL), with no substantial differences between the parent-only and parent-child groups [34].

Health-related quality of life and self-esteem

Two trials measured children’s self-esteem [26, 31]. One study reported narratively that there were no improvements in health-related quality of life but reported no data [32] and so it is not included here. Jansen et al. [31] found significant increases in physical appearance self-esteem post-intervention (three months) for both parent-only and waitlist control groups that were maintained at follow-up. There were no between-group differences. Eldridge et al. [26] looked more specifically at changes in children’s body self-esteem using the validated Body Esteem Scale (BES), which has three subscales - BES-Appearance, BES-Weight Satisfaction, and BES-Attribution. They found that both the parent-only and the minimal contact control intervention significantly increased children’s BES-Appearance scores and significantly decreased their BES-Weight dissatisfaction scores from pre to post-intervention (eight months) and at six month follow-up. Again, there were no between-group differences.

Child mental health

Only one study reported mental health outcomes for children [34], with findings suggesting significant linear decreases between baseline and 6-month follow-up for depressive feelings and for all anxiety measures (p < 0.001). There were no group differences in behaviour, depressive feelings and anxiety in children between parent-only and parent-child interventions (p > 0.1). These results should be interpreted with caution due to high risk of attrition bias given the high rates of drop-out and failure to use adequate means to address this in the analysis (e.g. no ITT analysis conducted).

Parenting

Three studies reported outcomes assessing parenting [29, 32, 33] but no studies reported outcomes assessing the parent-child relationship. Two studies found no effect on parenting style [29] or parenting skills [33]. One study reported significant between-groups differences in favour of the parent-only intervention in relation to parental concerns about the child’s weight, however, this difference had disappeared by follow-up [32]. Again, measures of parenting varied across all three studies (see Table 5).

Factors associated with outcomes

The second aim of this review was to identify any factors associated with intervention outcomes. Seven studies conducted further analysis to identify potential factors associated with treatment success (See Table 5; [24, 28,29,30,31, 36, 37], which was defined in all seven studies as a decrease in the child’s weight or BMI.

In terms of process variables, four studies reported higher parental session attendance to be correlated with weight-based outcomes [29, 31, 37]]. Using stepwise regression analyses, one study found that level of attendance of the agent of change in sessions explained 28% (r 2 0·28; P < 0·003) of the variability in the child’s weight status at the end of the six-month intervention [29]. Another study found a correlation between attendance and change in child weight status for the parent-child group from baseline to 3-month follow-up (r = −0.382, P = 0.005) but not for the parent-only group. This association had disappeared at two-year follow-up [37]. Change in parent BMI during intervention was found to be significantly correlated with child BMI change in the parent-only group [24].

In terms of environmental changes, two studies reported on changes in obesogenic factors in the child’s environment [24, 29]. One found improvement in obesogenic load in the house to explain 11% of the variance in the improvement of children’s weight status (r2 0·49; P < 0·02) [29]. The other study found pre-post changes in the obesogenic home food availability to be significantly correlated with pre-post changes in parent and children’s BMI in the parent-only intervention group (r = 0.45, p < 0.05) [24].

Five studies identified several socio-demographic characteristics as affecting outcomes in weight-management interventions [28,29,30,31, 36]. Two studies identified child weight status at baseline and the family’s socioeconomic status (SES) as potential predictors of treatment success [28, 31], however, they reported opposing findings. Jansen et al. [31] found that child baseline BMI percentile was the strongest mediator of treatment success: the lower the BMI percentile at the start of treatment, the larger the decrease in BMI percentile. However, Golan et al. [28] found the success of the intervention to be independent of the degree of overweight of either the child or parent at baseline. Jansen et al. [31] also found that, contrary to their expectations, lower SES was associated with greater treatment success. Golan et al. [28] found exactly the opposite: higher SES was associated with greater treatment success. The age of the overweight child was also reported to be a significant predictor; the younger the child, the larger the BMI decrease [31]. This finding was in line with another study that reported for children younger than 11 years, those in the parent-only intervention experienced an approximately 50% greater decrease in weight status at follow-up relative to those in the parent-child intervention [30]. However, children 11 years and older in the parent-child intervention experienced an approximately 50% greater decrease in weight status relative to those in the parent-only intervention. This finding suggests that older children may experience greater benefit from a parent-child intervention as they may be better able to use the skills taught by participating.

Finally, in one study a statistically significant negative correlation was shown between permissive parenting style and changes in BMI in both groups [29].

Discussion

The present systematic review examined the effectiveness of parent-only group-based healthy lifestyle interventions for improving outcomes for children and adolescents across a range of biomedical, psychological and behavioural outcomes. The aims were to (1) assess their effectiveness in relation to changes in health behaviours and psychological wellbeing, as well as more traditional measures of weight/BMI, and where reported, (2) to identify the potential factors associated with treatment outcomes. There was considerable heterogeneity between included trials in relation to intervention components, comparators, sample sizes and outcome measures. Many trials were not of adequate methodological quality, non-completion rates of the studies were generally high and few studies accounted for these in their analysis. These issues made it difficult to compare results across studies and this must be considered when interpreting the existing findings.

Summary of main results

BMI and weight change

BMI/weight change was the only outcome measure consistently reported across the 15 included studies. Furthermore, 14 of the 15 studies focused on children or adolescents that were overweight or obese, with only one study including children of normal weight [24]. The lack of studies focusing on normal weight children or reporting on non-weight related outcomes is notable given the need to focus on the prevention, as well as treatment of childhood obesity and the importance of other indices of health (e.g. self-esteem, health behaviours) for children’s well-being.

Overall, all studies except one [27] found parent-only interventions to be effective in producing significant decreases in child BMI and weight variables from pre to post-intervention and, in most trials, these changes were either maintained or continued to improve at follow-up. It is important to note that only one trial [37] reported outcomes over a relatively long period of follow-up (e.g. over two years). Whether changes such as those mentioned here can be maintained over the long-term remains to be determined.

In trials comparing parent-only interventions with a parent-child or child only intervention, while two studies showed an increased reduction in the degree of overweight in the parent-only groups compared with either the parent-child and child-only interventions, the other four studies’ results suggest that parent-only interventions are no different to parent–child interventions with regard to their effectiveness in the treatment of childhood overweight and/or obesity. These results are in line with three previous reviews in this area in which parent-only interventions appeared to be as effective as interventions that adopted the traditional model where the parent and child were both involved in the intervention [12,13,14]. As such, given the limited resources (e.g. health care resources, health promotion programs, staffing) often experienced within public health systems, parent-only group-based interventions for childhood obesity may be a more cost-effective option than a parent-child (family-based) intervention. Of note, the majority of the included studies focused on children rather than adolescents. One study within this review reported older children to experience greater benefits from a family-based intervention than younger children [30]. The study authors suggested that older children may be better able to use the skills taught and experiences obtained by participating in family interventions [30]. In addition, it seems logical to conclude that the younger the child, the more influence parents have on the eating and exercise habits of the child. As the child becomes older, parents are no longer their most important role models (peers take over that role) [38, 39].

This review found that parent-only interventions were superior to waitlist controls and similar in effect to parent-child and minimal contact controls on child BMI and weight. These findings are in line with a previous Cochrane review [14]. However, consistent with findings reported in the review by Ewald et al. [13], we found that the overall trend was for parent-only interventions to experience higher dropouts compared to the parent-child interventions. Ewald et al. [13] argued that taking up the responsibility for their child’s healthy weight may be overwhelming and lead to higher dropouts in the parent-only groups [34]. Thus, parents who participate in parent-only programmes need strong motivation but also the support of extended family that should not undermine the efforts of the lead parent [40]. It is also worth considering the relationship between the personnel delivering the intervention and the parent receiving it. Eldridge et al. [26] utilised personnel that had previously developed relationships with parents attending the programme and they reported overall participation from pre to post intervention to be over 90% in the parent-only group.

Behaviour change

Behaviour change outcomes in children, including energy consumption, physical activity, modification of the home food environment and problem behaviours were reported less consistently across trials and there was large heterogeneity in the outcome measures employed between trials. Overall, findings between studies on the effectiveness of parent-only interventions for changing children’s behaviour tended to be conflicting and as such, coupled with the low quality of these trials, difficult to interpret.

Across trials which included children’s energy intake and/or obesogenic habits in the home as outcome measures, findings indicated that parent-only interventions were effective at reducing both behaviours and that these changes continued to be maintained at follow-up. Trials generally reported no substantial differences between groups on these two behavioural outcomes. Due to the equivocal findings reported across trials in relation to children’s eating behaviours (e.g. intake of healthy and unhealthy food items) it is not possible to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of parent-only interventions in changing children’s eating behaviours. Similarly, findings in relation to physical activity behaviours and sedentary behaviours were mixed, with some studies reporting increases in physical activity levels and decreases in sedentary behaviours (albeit small) following parent-only interventions, while others reported no change following intervention. All studies reported that there were no substantial differences between groups.

The equivocal findings between studies on measures of eating behaviour and physical activity may be a factor of how these variables were measured. There was considerable variability regarding the measures used for these constructs, with no two studies using the same measure and with some examining the health behaviours of the family or parent and child together as opposed to separately. Further, all studies used self-report measures of eating behaviour and physical activity, which is common in research on health behaviours [41]. However, such self-report measures may have questionable validity as the correlation between self-reported and objectively measured activity can be quite low [42].

Self-esteem and mental health change

Just two of the included studies measured the effectiveness of parent-only healthy lifestyle interventions on children’s self-esteem. This is notable considering that self-esteem is reported to be significantly lower in overweight and obese children compared to their normal weight peers [43] and self-esteem is reported to directly influence trajectory of weight gain in children [44] and engagement with treatment in adulthood [45, 46].

Across both studies, children in the parent-only intervention experienced an increase in several indices of self-esteem but primarily physical appearance self-esteem from pre to post-intervention and at up to 6-month follow-up with no between-group differences. Lack of between-group differences suggests that just waiting for interventions to promote healthy living or simply providing families with written information about best practices may have significant beneficial effects on important dimensions of self-esteem and body image for children and adolescents.

Only one study reported mental health outcomes for children following either a parent-only or parent-child specialised CBT intervention. Both interventions led to improvements in children’s anxious and depressive feelings and overall behaviour problems, which were maintained at 6-month follow-up, with no differences between groups. However, these results should be interpreted with caution given the high dropout rates in both intervention groups and no reports of appropriate means to address attrition in the analyses. As depressive symptoms might be a valuable predictor for adolescent and adult obesity [47], future studies in this area should look into the impact of parent-only healthy lifestyle interventions on psychological parameters in children and whether improvement in psychological parameters is associated with weight reduction and long-term maintenance of weight reduction.

Change in parenting style

Despite the wide support by existing research regarding targeting parents for improvement of parenting skills in the treatment of childhood obesity [48,49,50,51] only three studies included changes in parenting style as an outcome measure. While parenting style did not change as a result of the parent-only interventions in any of the studies, a trend was found in one study between parental control and child weight. Controlling a child’s feeding practices most probably contributes to, rather than prevents, childhood obesity and eating problems [52]. Parental control interferes with a child’s ability to attend to internal cues of hunger and satiety that serve self-regulation [53]. Many parents of obese children control the child’s behaviour rather than regulate the obesogenic factors in the home environment. As such, interventions should explicitly foster authoritative parenting with an emphasis on taking responsibility and enforcing a healthy environment in the house, setting limits on the time spent in sedentary activity, and avoiding insensitivity and/or unresponsiveness to the feeding cues from the child.

Factors associated with outcomes

Another aim of this review was to identify potential factors associated with outcomes from parent-only healthy lifestyle programmes. Process variables, such as parental attendance and parent BMI change were positively associated with child weight loss. This is in line with previous research on attendance [54,55,56]. Given that drop-out rates from parent-only weight-management interventions tends to be high [57], this finding emphasises the importance of identifying individuals at risk of dropout for extra support. Consistent with previous findings [58, 59], parent BMI change during the intervention was also associated with child weight change. This may reflect the importance of parenting changes, such as modelling of healthy weight control behaviours.

Change in obesogenic factors in the child’s environment, particularly the availability and accessibility of foods and beverages, was associated with improvements in children’s weight and BMI. Many parents of obese children control the child’s behaviour rather than regulate the obesogenic factors in the home environment. Again, this points to the need for future interventions to target broad parenting skills and practices.

Studies on the children’s own characteristics found that younger child age was associated with better short-term weight loss, which replicates most of the existing literature [58, 60,61,62].

The contradictory findings in relation to the families SES status and the child’s weight outcomes are not uncommon in the literature [63]. It has been assumed that a lower SES may negatively influence a parent’s ability to facilitate healthy eating patterns in their child [64], however, several studies have found that the family SES, including family structure and parental employment status, does not play a role in predicting obesity treatment outcome [60, 65, 66]. The contradictory findings between the studies in this review may be as a result of the differing measures they used to assess SES, which has previously been reported in the literature to be a problem in health research [67].

Strengths, limitations and implication for research and practice

This study adds to the findings of a recent systematic review [14] while also extending them by including children of all weight status, including children’s wider health-related behaviours and limiting interventions to those that are strictly group-based. Findings show that parent-only interventions are effective, at least in the short-term, at reducing the weight status of children, improving health behaviours and psychological wellbeing, and have similar effects to parent-child interventions and minimal-contact control interventions. This review is also the first to summarise findings on those variables that might impact outcomes. Factors such as parental attendance, modifications to the home food environment, the child’s age, baseline weight and family SES status are potentially important predictors that may enhance or impede outcomes.

There are several limitations of the existing literature. Most of the studies included had small sample sizes and large dropout rates and losses to follow-up which were not adequately addressed in the analysis and creates risk of bias. Another limitation of this review is that there was substantial methodical and clinical heterogeneity between individual trials making it difficult to synthesise findings. In addition, few trials reported secondary outcomes of interest or outcomes over a relatively long period of follow-up (e.g. over two years). As such, future research can address these shortcomings by using larger sample sizes, investigating attrition and reporting on important secondary outcomes over time. Further research is also needed to understand the mechanisms by which these interventions may improve outcomes for children, especially in those areas that yield conflicting findings (e.g. SES).

Current findings have important implications for practice. Parent-only interventions had similar effects compared with parent-child interventions and minimal contact controls for weight as well as broader health behaviours and psychological wellbeing. Thus, parent-only interventions may initially appear to be a more cost-effective, less resource intensive option than parent-child (family-based) interventions. However, parent-only interventions tend to experience higher dropouts rates than parent-child interventions. Understanding who may benefit from different intervention types and why is crucial. For example, findings from the current review demonstrate that younger children who had a lower initial relative weight appeared to benefit most from parent-only interventions, particularly those of shorter duration and less intensity. Further research is needed to understand when parent-only interventions are appropriate and when family-based interventions may be necessary. Finally, given the comparable results between parent-only and minimal control interventions, incorporating such information into health care systems, parental consultations with healthcare professionals, education settings, and via mail-delivery could provide additional, low-cost benefits on health outcomes for families and their children.

Data availability

Given that this was a systematic review, there is no raw data associated with this study. However, the search string used is outlined in the methods section of the study.

References

Eckersley RM. Losing the battle of the bulge: causes and consequences of increasing obesity. Med J Aust. 2001;174:590–2. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143446.x.

Mokdad A, Ford E, Bowman B, Dietz W, Vinicor F, Bales V, et al. Prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and obesity-related health risk factors, 2001. JAMA. 2003;289:76.

Parsons TJ, Power C, Logan S, Summerbell CD. Childhood predictors of adult obesity: a systematic review. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:S1–107. PMID: 10641588.

Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2008;9:474–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00475.x.

Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:869–73. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199709253371301.

Al-Khudairy L, Loveman E, Colquitt JL, Mead E, Johnson RE, Fraser H, et al. Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese adolescents aged 12 to 17 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD012691 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012691.

Mead E, Brown T, Rees K, Azevedo LB, Whittaker V, Jones D, et al. Diet, physical activity and behavioural interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese children from the age of 6 to 11 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD012651 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012651.

Summerbell CD, Moore HJ, Vögele C, Kreichauf S, Wildgruber A, Manios Y, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the development of obesity prevention programs targeted at preschool children. Obes Rev. 2012;13:129–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00940.x.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Obesity in children and young people: prevention and lifestyle weight management programmes. NICE Guidelines. 2015 QS94. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs94 (accessed 17 March 2021).

Oude Luttikhuis H, Baur L, Jansen H, Shrewsbury VA, O’Malley C, Stolk RP, et al. Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Jan;CD001872. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001872.pub2. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019 Mar 07;3:CD001872. PMID: 19160202.

Upton D, Upton P, Bold J, Peters DM Regional evaluation of weight management programmes for children and families. 2012. http://www.obesitywm.org.uk/resources/Worcester_Report_Fina.pdf (accessed 02 March 2021).

Jull A, Chen R. Parent-only vs. parent-child (family-focused) approaches for weight loss in obese and overweight children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2013;14:761–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12042.

Ewald H, Kirby J, Rees K, Robertson W. Parent-only interventions in the treatment of childhood obesity: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J Public Health (Oxf). 2014;36:476–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdt108.

Loveman E, Al-Khudairy L, Johnson RE, Robertson W, Colquitt JL, Mead EL, et al. Parent-only interventions for childhood overweight or obesity in children aged 5 to 11 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD012008 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012008.

Brown T, Moore TH, Hooper L, Gao Y, Zayegh A, Ijaz S, et al. Interventions for preventing obesity in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7:CD001871 https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001871.pub4.

Morgan F, Weightman A, Whitehead S, Brophy S, Morgan H, Turley R, et al. Effectiveness and cost effectiveness of lifestyle weight management services for children and young people, 2013 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph47/evidence/review-of-effectiveness-and-cost-effectiveness-pdf-430360093. Accessed 02 March 2021.

Griffiths LJ, Parsons TJ, Hill AJ. Self-esteem and quality of life in obese children and adolescents: a systematic review. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010;5:282–304. https://doi.org/10.3109/17477160903473697.

Hayes JF, Altman M, Coppock JH, Wilfley DE, Goldschmidt AB. Recent updates on the efficacy of group based treatments for pediatric obesity. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep. 2015;9:16 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12170-015-0443-8.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–9, W64. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1.

Prictor M, Hill S. Cochrane consumers and communication review group: leading the field on health communication evidence. J Evid Based Med. 2013;6:216–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12066.

Tarrier N, Wykes T. Is there evidence that cognitive behaviour therapy is an effective treatment for schizophrenia? A cautious or cautionary tale? Behav Res Ther. 2004;42:1377–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2004.06.020.

Wykes T, Steel C, Everitt B, Tarrier N. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: effect sizes, clinical models, and methodological rigor. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:523–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbm114.

Anderson LM, Symoniak ED, Epstein LH. A randomized pilot trial of an integrated school-worksite weight control program. Health Psychol. 2014;33:1421–5. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000007.

Boutelle KN, Cafri G, Crow SJ. Parent-only treatment for childhood obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19:574–80. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2010.238.

Eldridge G, Paul L, Bailey SJ, Ashe CB, Martz J, Lynch W. Effects of parent-only childhood obesity prevention programs on BMIz and body image in rural preteens. Body Image. 2016;16:143–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.12.003.

Esfarjani F, Khalafi M, Mohammadi F, Mansour A, Roustaee R, Zamani-Nour N, et al. Family-based intervention for controlling childhood obesity: an experience among Iranian children. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4:358–65.

Golan M, Weizman A, Apter A, Fainaru M. Parents as the exclusive agents of change in the treatment of childhood obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:1130–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/67.6.1130.

Golan M, Kaufman V, Shahar DR. Childhood obesity treatment: targeting parents exclusively v. parents and children. Br J Nutr. 2006;95:1008–15. https://doi.org/10.1079/bjn20061757.

Janicke DM, Sallinen BJ, Perri MG, Lutes LD, Huerta M, Silverstein JH, et al. Comparison of parent-only vs family-based interventions for overweight children in underserved rural settings: outcomes from project STORY. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:1119–25. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.162.12.1119.

Jansen E, Mulkens S, Jansen A. Tackling childhood overweight: treating parents exclusively is effective. Int J Obes (Lond). 2011;35:501–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2011.16.

Mazzeo SE, Kelly NR, Stern M, Gow RW, Cotter EW, Thornton LM, et al. Parent skills training to enhance weight loss in overweight children: evaluation of NOURISH. Eat Behav. 2014;15:225–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.01.010.

Moens E, Braet C. Training parents of overweight children in parenting skills: a 12-month evaluation. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2012;40:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465811000403.

Munsch S, Roth B, Michael T, Meyer AH, Biedert E, Roth S, et al. Randomized controlled comparison of two cognitive behavioral therapies for obese children: mother versus mother-child cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychother Psychosom. 2008;77:235–46. https://doi.org/10.1159/000129659.

Raynor HA, Osterholt KM, Hart CN, Jelalian E, Vivier P, Wing RR. Efficacy of U.S. paediatric obesity primary care guidelines: two randomized trials. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7:28–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2047-6310.2011.00005.x.

Sandvik P, Ek A, Eli K, Somaraki M, Bottai M, Nowicka P. Picky eating in an obesity intervention for preschool-aged children - what role does it play, and does the measurement instrument matter? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16:76 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0845-y.

Yackobovitch-Gavan M, Wolf Linhard D, Nagelberg N, Poraz I, Shalitin S, Phillip M, et al. Intervention for childhood obesity based on parents only or parents and child compared with follow-up alone. Pediatr Obes. 2018;13:647–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12263.

Albert D, Chein J, Steinberg L. Peer influences on adolescent decision making. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2013;22:114–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412471347.

Biddle BJ, Bank BJ, Marlin MM. Parental and peer influence on adolescents. Soc Forces. 1980;58:1057–79. https://doi.org/10.2307/2577313.

Stewart L, Chapple J, Hughes AR, Poustie V, Reilly JJ. Parents’ journey through treatment for their child’s obesity: a qualitative study. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:35–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2007.125146.

Conner M, Norman P. Health behaviour: current issues and challenges. Psychol Health. 2017;32:895–906. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2017.1336240.

Rhodes RE, Janssen I, Bredin SSD, Warburton DER, Bauman A. Physical activity: Health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychol Health. 2017;32:942–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2017.1325486.

Rankin J, Matthews L, Cobley S, Han A, Sanders R, Wiltshire HD, et al. Psychological consequences of childhood obesity: psychiatric comorbidity and prevention. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2016;7:125–46. https://doi.org/10.2147/AHMT.S101631.

French SA, Story M, Perry CL. Self-esteem and obesity in children and adolescents: a literature review. Obes Res. 1995;3:479–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00179.x.

Fabricatore AN, Wadden TA, Moore RH, Butryn ML, Heymsfield SB, Nguyen AM. Predictors of attrition and weight loss success: results from a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:685–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.05.004.

Honas JJ, Early JL, Frederickson DD, O’Brien MS. Predictors of attrition in a large clinic-based weight-loss program. Obes Res. 2003;11:888–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2003.122.

Hasler G, Pine DS, Kleinbaum DG, Gamma A, Luckenbaugh D, Ajdacic V, et al. Depressive symptoms during childhood and adult obesity: the Zurich Cohort Study. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:842–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.mp.4001671.

Epstein LH, Myers MD, Raynor HA, Saelens BE. Treatment of pediatric obesity. Pediatrics. 1998;101:554–70.

Israel AC, Stolmaker L, Andrian CA. The effects of training parents in general child management skills on a behavioral weight loss program for children. Behav Ther. 1985;16:169–80.

Epstein LH. Family-based behavioural intervention for obese children. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996;20:S14–21.

Barlow SE, Dietz WH. Obesity evaluation and treatment: expert committee recommendations. The maternal and child health bureau, health resources and services administration and the department of health and human services. Pediatrics. 1998;102:E29 https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.102.3.e29.

Johnson SL, Birch LL. Parents’ and children’s adiposity and eating style. Pediatrics. 1994;94:653–61.

Birch LL, Davison KK. Family environmental factors influencing the developing behavioral controls of food intake and childhood overweight. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2001;48:893–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70347-3.

Theim KR, Sinton MM, Goldschmidt AB, Van Buren DJ, Doyle AC, Saelens BE, et al. Adherence to behavioral targets and treatment attendance during a pediatric weight control trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2013;21:394–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20281.

Kalarchian MA, Levine MD, Arslanian SA, Ewing LJ, Houck PR, Cheng Y, et al. Family-based treatment of severe pediatric obesity: randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1060–8. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-3727.

Wrotniak BH, Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Roemmich JN. The relationship between parent and child self-reported adherence and weight loss. Obes Res. 2005;13:1089–96. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2005.127.

Hull PC, Buchowski M, Canedo JR, Beech BM, Du L, Koyama T, et al. Childhood obesity prevention cluster randomized trial for Hispanic families: outcomes of the healthy families study. Pediatr Obes. 2018;13:686–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijpo.12197.

Goldschmidt AB, Best JR, Stein RI, Saelens BE, Epstein LH, Wilfley DE. Predictors of child weight loss and maintenance among family-based treatment completers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82:1140–50. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037169.

Wrotniak BH, Epstein LH, Paluch RA, Roemmich JN. Parent weight change as a predictor of child weight change in family-based behavioral obesity treatment. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:342–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.158.4.342.

Braet C. Patient characteristics as predictors of weight loss after an obesity treatment for children. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14:148–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2006.18.

Goossens L, Braet C, Van Vlierberghe L, Mels S. Weight parameters and pathological eating as predictors of obesity treatment outcome in children and adolescents. Eating Behav. 2009;10:71–3.

Sabin MA, Ford A, Hunt L, Jamal R, Crowne EC, Shield JP. Which factors are associated with a successful outcome in a weight management programme for obese children? J Eval Clin Pract. 2007;13:364–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2006.00706.x.

Müller MJ, Danielzik S, Pust S. School- and family-based interventions to prevent overweight in children. Proc Nutr Soc. 2005;64:249–54. https://doi.org/10.1079/pns2005424.

Epstein LH, Wing RR. Behavioral treatment of childhood obesity. Psychol Bull. 1987;101:331–42.

Reinehr T, Brylak K, Alexy U, Kersting M, Andler W. Predictors to success in outpatient training in obese children and adolescents. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:1087–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0802368.

Wiegand S, Keller KM, Lob-Corzilius T, Pott W, Reinehr T, Röbl M, et al. Predicting weight loss and maintenance in overweight/obese pediatric patients. Horm Res Paediatr. 2014;82:380–7. https://doi.org/10.1159/000368963.

Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Chideya S, Marchi KS, Metzler M, et al. Socioeconomic status in health research: one size does not fit all. JAMA. 2005;294:2879–88. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.294.22.2879.

Acknowledgements

Both authors wish to acknowledge their main affiliation with the Department of Psychology, University College Dublin, Ireland. Also, thanks to Marta Bustillo, UCD Librarian, for helpful comments on the screening of articles. No funding was provided for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FMD and KL designed the study. FMD independently carried out the literature search and screening of articles, with KL acting as a second reviewer and extracting data from 20% of studies. FMD analysed the data with both authors contributing to interpretation of findings. FMD drafted the original manuscript with both authors contributing to the review and editing process. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. KL acted as supervisor throughout the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

McDarby, F., Looney, K. The effectiveness of group-based, parent-only weight management interventions for children and the factors associated with outcomes: a systematic review. Int J Obes 48, 3–21 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-023-01390-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41366-023-01390-6

- Springer Nature Limited