Abstract

Lissencephaly is a rare brain malformation characterized by abnormal neuronal migration during cortical development. In this study, we performed a comprehensive genetic analysis using next-generation sequencing in 12 unsolved Japanese lissencephaly patients, in whom PAFAH1B1, DCX, TUBA1A, and ARX variants were excluded using the Sanger method. Exome sequencing (ES) was conducted on these 12 patients, identifying pathogenic variants in CEP85L, DYNC1H1, LAMC3, and DCX in four patients. Next, we performed genome sequencing (GS) on eight unsolved patients, and structural variants in PAFAH1B1, including an inversion and microdeletions involving several exons, were detected in three patients. Notably, these microdeletions in PAFAH1B1 could not to be detected by copy number variation (CNV) detection tools based on the depth of coverage methods using ES data. The density of repeat sequences, including Alu sequences or segmental duplications, which increase the susceptibility to structural variations, is very high in some lissencephaly spectrum genes (PAFAH1B1, TUBA1A, DYNC1H1). These missing CNVs were due to the limitations of detecting repeat sequences in ES-based CNV detection tools. Our study suggests that a combined approach integrating ES with GS can contribute to a higher diagnostic yield and a better understanding of the genetic landscape of the lissencephaly spectrum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lissencephaly is a rare neuronal migration disorder that occurs about 1 per 100,000 live births and impacts brain development during the cortical formation process, resulting in a brain with only four or three layers rather than the typical six [1]. Although it does not progress over time, it is associated with significant challenges such as intellectual disability, developmental delays, and seizures [2]. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of “classical lissencephaly” showed a broad spectrum comprised of agyria (cortical thickness exceeding 10 mm), pachygyria (gyral thickness between 4 and 9 mm), and subcortical band heterotopia [3, 4].

Previous studies have revealed that approximately 80% of classical lissencephaly patients had pathogenic variants in major causative genes [5], including PAFAH1B1 (49.3%), DCX (28.3%), TUBA1A, ARX, and DYNC1H1 [6,7,8,9,10]. Patients with each causative gene show characteristic brain images, including occipital lobe-dominant or a posterior-anterior (p > a) gradient in PAFAH1B1 variants, frontal lobe-dominant lesions or a > p gradient in DCX variants, basal ganglia abnormalities and external genital abnormalities in ARX variants, and corpus callosum agenesis, pontocerebellar hypoplasia, and microcephaly in TUBA1A variants. Despite these well-established gene-phenotype correlations, approximately 20% of lissencephaly patients remain unsolved. These atypical cases have a heterogeneous genetic background, and 55 genes have been registered as lissencephaly-related genes in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD) (Table S1).

Not only sequence variants, but also copy number variants (CNVs) and structural variants (SVs) have been found in lissencephaly patients. Therefore, appropriate analysis methods, including target sequencing of candidate genes, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA), and fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis, are needed for detecting each type of variant. Exome sequencing (ES) and genome sequencing (GS) offer the benefit of detecting a broader range of genetic variations, including CNVs, SVs and deep intronic variants, and they can uncover novel lissencephaly-related genes and genomic abnormalities that are difficult to detect by conventional analysis methods. However, the added value of GS in the diagnostic workflow for lissencephaly patients, particularly in identifying SVs in genes like PAFAH1B1, has not been fully explored.

Here, we performed a comprehensive genetic analysis using ES and GS on 12 Japanese patients with lissencephaly. This genetic approach helped us discover structural variants undetectable by ES and brought a high diagnostic yield. This study particularly clarified the limitations of ES analysis in detecting CNVs in genes with high repetitive sequence content and suggested an efficient diagnostic approach for patients with lissencephaly.

Methods

Patients

The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of Showa University School of Medicine and Hamamatsu University School of Medicine. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents. Clinical information including family history, medical history, findings of neurological and physical examinations, general biochemical analyses and brain imaging was collected by the physician in charge. We selected 12 lissencephaly patients, in whom PAFAH1B1, DCX, TUBA1A, and ARX variants were excluded using the Sanger sequencing according to brain image findings, clinical symptoms and sex. A flow chart of our analysis is illustrated in Fig. S1.

Exome sequencing (ES)

Genomic DNA extracted from the blood leukocytes of the patients and parents was captured using the SureSelect Human All Exon V6 kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) or an xGen Exome Research Panel kit (IDT, Coralville, IA) and sequenced on NextSeq 500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) with 151-bp or 76-bp paired-end reads. Exome data processing, variant calling, and variant annotation were carried out as previously described [11]. We also investigated copy number variations (CNVs) using the eXome-Hidden Markov Model (XHMM) [12] and modified Nord’s method (jNord) [13] in 55 lissencephaly-related genes registered in the HGMD (Table S1). Segregation of candidate variants was confirmed by Sanger sequencing using trio DNA samples, and the pathogenicity of these variants was classified according to the guidelines of the American College of Medical Genetics and the Association of Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) [14] and the recommendations of the ClinGen Sequence Variant Interpretation (SVI) Working Group.

Genome sequencing (GS)

GS was commissioned by BGI Japan Corp. (Kobe, Japan). The sequencing was conducted using DNBSEQ (MGI TECH, Shenzhen, China) with 150 bp paired-end reads. Data processing, variant calling, and variant annotation followed procedures previously described [15]. CNV, SV, and transposon detection were performed using Canvas v1.40.0, Manta v1.6.0, and TEMP2 v0.1.4, respectively [16,17,18]. Alignments were visualized using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) v2.16.0 (available at https://igv.org/). De novo assembly of aberrantly aligned read pairs was performed using Megahit v1.2.9 [19]. Detected SVs were confirmed by breakpoint-specific polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and primer information is provided separately in the Supplementary information (Table S2).

Evaluation of repetitive sequences

We obtained human data regarding RepeatMasker and Segmental Dups (SegDup) as browser extensible data (BED) format via Table Browser (GRCh38/hg38) on the UCSC genome browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/) to assess retrotransposons and segmental duplications in the genomic regions of the PAFAH1B1, DCX, TUBA1A, DYNC1H1, and ARX genes. Transposons, particularly those from the Alu and LINE-1 families known to be significantly involved in structural abnormalities, were analyzed. The Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST, https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) was used to search for homology in Alu pairs. Homologous regions were searched by “megablast”, and the similarity of the aligned sequences was evaluated based on the “word size” parameter. Pairs that could not be aligned by “megablast” had their homology calculated using “discontiguous megablast”. We performed statistical analysis using EZR v.1.64 software [20] and conducted Fisher’s exact test.

Results

Clinical characteristics of patients

The clinical characteristics of all patients are summarized in Table 1. Seven males and five females born to non-consanguineous healthy parents participated in this study. Paternal information and samples were unavailable for patient 6. All patients were born at term except for patient 1, delivering at 36 weeks and four days. Birth asphyxia was observed in three patients (25.0%). Primary microcephaly with head circumference less than −2.0 SD was present in two patients, and the median age at the final evaluation was 12 months (interquartile range, 3.5 to 59.5).

From the brain imaging, the median Dobyns lissencephaly grade [21] was 3. The gradient of lissencephaly was posterior dominant (p > a) in five patients (41.7%), anterior dominant (a > p) and diffuse each in three (25.0%), and temporal dominant in one. Other findings included cerebellar hypoplasia and abnormalities of the corpus callosum in three patients each, and ventricular enlargement in seven. Neurological findings showed intellectual disability in all patients, developmental delay in seven (58.3%), and epilepsy in 10 (83.3%). Physical examinations revealed dysmorphic features in three patients, and no genital abnormalities were observed.

Identification of variants related to lissencephaly

A summary of the genetic analysis for 12 patients is presented in Table 2. Initially, case-only ES was performed for all patients, and five pathogenic variants in four genes, CEP85L, DYNC1H1, LAMC3, and DCX, were identified in four patients (33.3%). Three de novo variants in CEP85L, DYNC1H1, and DCX were novel, but another missense variant on the same residue in DYNC1H1 (NM_001376.4: c.9874G>T p.(Ala3292Ser)) had been registered as variant of uncertain significance (VUS) in ClinVar (VCV001043835.6). Both compound heterozygous LAMC3 variants (NM_006059.4:c.976+1G>A and c.4102_4105del, p.(Arg1368Serfs*48)) have been reported as pathogenic in a previous study [22]. The c.976+1G>A splice site variant was registered as pathogenic in ClinVar (VCV001324651.4) and HGMD (CS1212385). Multiple in silico variant pathogenicity prediction tools indicated that all variants may be deleterious [23]. Based on these results, these variants were classified as Pathogenic or Likely Pathogenic according to the ACMG/AMP guideline and SVI recommendations (Table 2). We identified compound heterozygous missense variants in DARS2 and WDR81 in patient 9 and 12, respectively. Both genes are associated with leukoencephalopathy or hydrocephalus, and some brain abnormalities in patient 9 and 12 were similar to these gene-associated disorders [24]. These missense variants were predicted to be deleterious and transmitted from their parents in trans, however, the pathogenicity of these variants was classified as VUS.

Detection of structural variants in PAFAH1B1

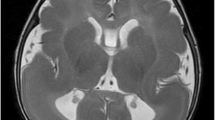

GS was additionally conducted on eight unsolved patients. De novo SVs, including partial deletions and an inversion of PAFAH1B1, were detected in three out of eight (37.5%). In patient 1, a “Breakend” on the short arm of chromosome 17 was detected with Manta software, and a paracentric inversion of approximately 90 kb encompassing the PAFAH1B1 gene was inspected with IGV viewer (Fig. 1A). Breakpoint sequences involving PAFAH1B1 intron 5 and RAP1GAP2 intron 1 were determined by de novo assembly of aberrant reads by Megahit, and were confirmed by breakpoint PCR (Fig. 1B–D). In patient 5, an approximately 11 kb deletion spanning from PAFAH1B1 intron 9 to CLUH exon 1 was detected by Manta and Canvas, and confirmed by breakpoint PCR (Fig. S2). In patient 10, a 160 kb deletion from PAFAH1B1 intron 2 to METTL16 intron 2 was detected by Canvas, and confirmed by Breakpoint PCR (Fig. S3).

Identification of an Inversion in PAFAH1B1 in Patient 1. A Integrative Genomics Viewer image using GS data of Patient 1 (top) and a healthy control (bottom). This image displays a structural variant with breakpoints indicated by Manta, confirming soft clipping reads within the PAFAH1B1 gene. B The region of the paracentric inversion identified by de novo assembly is illustrated on the UCSC Genome Browser (https://genome.ucsc.edu/). PCR primer sets for proximal (light blue arrows) and distal (orange arrows) breakpoints (Table S2) were designed to specifically amplify the ends of the inversion in the patient. Breakpoint PCR (left side) and Sanger sequencing (right side) results of the proximal (C) and distal (D) ends. PCR products of family 1 were electrophoresed on a 2% Tris-acetate-EDTA gel for 30 min. These products were absent in the parents, verifying that this inversion occurred de novo. Sanger sequencing results confirmed that the breakpoints are in intron 5 of PAFAH1B1 and intron 1 of RAP1GAP2. GS genome sequencing, PCR polymerase chain reaction, VT variant, WT wild-type

It has been suggested that the PAFAH1B1 gene has higher susceptibility to SVs compared to single nucleotide variants [25]. This high susceptibility to SVs is thought to result from the high density of Alu sequences within the PAFAH1B1 gene [26], which tend to induce non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR) or non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) between highly homologous Alu elements. We confirmed that SVs in our patients occurred at AluY or AluSx sequences, which are classified as evolutionarily “young Alu” considered to have high transposal activity [27] (Fig. 2).

Based on GS results, we retrospectively reanalyzed ES data of two patients with PAFAH1B1 deletions using jNord. Although we observed a trend of reduced read depth (Fig. 3), no SVs were called in the deleted regions.

Investigation of PAFAH1B1 copy number loss using modified Nord methods. A IGV of the PAFAH1B1 gene in Patient 10 and seven healthy controls. The red box indicates exon 3, which is deleted in the patient. B Modified Nord method (jNord) results for Patient 10 and three healthy controls. The coverage of each exon of PAFAH1B1 is plotted. In Patient 10, although no variants were called, the depth of exon 2 in PAFAH1B1 showed a decreasing trend. jNord analysis was performed on 32 samples using Agilent V6 Capture. C1-7, healthy controls (n = 7); IGV, Integrative Genomics Viewer; P10, Patient 10

Discussion

In this study, we performed comprehensive genetic analysis for 12 unsolved Japanese patients with lissencephaly spectrum and identified five nucleotide variants, two deletions and an inversion in seven patients (58.3%). Three of the five pathogenic nucleotide variants, c.232G>T, p.(Asp78Tyr) in CEP85L; c.9875C>T, p.(Ala3292Val) in DYNC1H1; and c.748C>T, p.(Gln250*) in DCX, were novel. A large-scale study for patients with lissencephaly had reported that approximately 80% of patients had pathogenic variants in lissencephaly-related genes [5]. The lower detection rate in our study, compared to previous reports, would be attributed to a pre-screening of the variants of PAFAH1B1, DCX, TUBA1A, and ARX based on the clinical phenotypes.

Genes encompassing highly homologous or numerous repetitive sequences, such as PAFAH1B1, are prone to structural abnormalities. Here, we analyzed the distributions of homologous or repetitive sequences, including Alu, LINE-1, and SegDups, in the top five causative genes for lissencephaly: PAFAH1B1, DCX, TUBA1A, DYNC1H1, and ARX. Whereas Alu sequences compose about 10% of the human genome on average [28], they exist in the entire gene regions with high density, at 35% for PAFAH1B1 and 27% for DYNC1H1 (Table 3). In addition to the density, other factors responsible for Alu recombination were equivalent in DYNC1H1 and PAFAH1B1 (Table S3). In contrast, TUBA1A, ARX, and DCX had no or low incidence rates of Alu sequences. DCX had the highest LINE-1 occupancy rate at 19%; however, this value was not particularly remarkable considering that approximately 20% of the human genome consists of LINE elements. TUBA1A had two SegDup regions with extremely high homology; each covered approximately half of the entire gene. Both of these homologous sequences also had high susceptibility to SVs.

Nonetheless, SVs in DYNC1H1 and TUBA1A are quite less than PAFAH1B1 [5]. One possibility is that there are differences in the sequence homology between Alu pairs at breakpoints in these genes. Homology between Alu sequences influences the repair mechanism of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) [29]. When the homology exceeds 97%, the highly accurate single-strand annealing repair is selected. Alternatively, as the homology decreases, error-prone NHEJ repair is favored, and at homologies below 80%, all DSBs are repaired by NHEJ. Studies using yeast have reported that when the homology of Alu falls below 86%, genomic instability is resolved, and homologous recombination does not occur [30]. These results suggest that homologous recombination between Alu elements may be restricted to a narrow homology range between 86-97%. The homology of typical Alu families is 70–75% [31], but the Alu pairs that caused NAHR in Patient 1 and 10 had high homology of 89% and 92%, respectively. This restriction could explain why Alu-mediated SVs are more frequently observed in PAFAH1B1. On the other hand, the 1802 bp nucleotide sequence of SegDup regions aligned in TUBA1A was completely identical. These highly homologous sequences may be less likely to develop SVs due to repair by single-strand annealing.

Since all NAHR in this study were related to AluY sequences, we focused on the homology of AluY sequences in PAFAH1B1 and DYNC1H1. We analyzed the sequence similarities for 28 pairs of AluY sequences in PAFAH1B1 and 55 pairs in DYNC1H1 (Table S4) using BLAST search [32]. There are two types of homologies: local similarity and global similarity. Local similarity means the similarity of short consecutive sequences, whereas global similarity concerns the similarity of entire sequence. Typically, “homology” refers to local similarity, often assessed using the BLAST algorithm. For sequences to be matched in BLAST, not only high similarity but also perfect identity of the homologous sequences is essential. Even with high local similarity, the presence of gaps can reduce the maximal segment pair (MSP), leading to no match. BLAST offers various algorithms with different sensitivities. BLAST algorithms are significantly influenced by the “word size,” which is the length of the initial seed sequence for alignment. “Megablast,” with a larger word size, detects regions with the highest homology, while “discontiguous megablast,” with a smaller word size, is used for sequences with lower homology. Interestingly, the AluY pairs of PAFAH1B1 show lower local similarity than those of DYNC1H1. However, while only 63.6% of Alu pairs matched in DYNC1H1 using “megablast”, 96.4% matched in PAFAH1B1, which is significantly higher (p < 0.001). Using the “discontiguous megablast” algorithm, all previously unmatched Alu pairs were successfully aligned. These findings suggested that although PAFAH1B1 has lower local similarity than DYNC1H1, homologous recombination is more likely to occur in PAFAH1B1 due to the longer regions of perfect matches within the homologous sequences, increasing the propensity for SVs in PAFAH1B1.

Although we utilized two types of CNV detection programs, XHMM [12] and jNord [13] for ES screening, two deletions including PAFAH1B1 were not detected. Both programs require a read depth of x30 to detect CNVs, and the ES data of all patients met this requirement. Notably, the XHMM program excludes regions with a high proportion (>10%) of homologous sequences masked by RepeatMasker from the analysis [12]. In contrast, jNord can process SegDup regions with less than 75% homology, whereas the original Nord requires at least one breakpoint in a unique sequence [33]. Consequently, detecting CNVs in regions with high repeat sequences, such as the Alu sequences of PAFAH1B1, is challenging using XHMM and jNord. These findings highlight the importance of careful examination of CNVs in genes with a high density of homologous sequences, and the potential contributions of SVs in these genes to lissencephaly might be underestimated.

Our findings indicate the limitations of identifying SVs in causative genes of lissencephaly using ES alone, emphasizing the importance of integrating additional diagnostic techniques. MLPA is effective for detecting CNVs in PAFAH1B1 [34], so we suggest that MLPA should be actively adopted as the first screening method for patients with lissencephaly. GS has an advantage in the comprehensive screening of pathogenic variants, including nucleotide variants in coding regions, deep-intronic variants affecting RNA splicing, and various structural abnormalities. Considering cost and variant detection efficiency, we propose a multi-step diagnostic workflow. The first step involves target sequencing and MLPA analysis for major classical lissencephaly genes. The second step is ES, and the final step is GS. This combined approach could improve diagnostic yield for patients suspected of lissencephaly.

Supplementary information is available on the Journal of Human Genetics website.

References

Oegema R, Barakat TS, Wilke M, Stouffs K, Amrom D, Aronica E, et al. International consensus recommendations on the diagnostic work-up for malformations of cortical development. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16:618–35.

Guerrini R, Filippi T. Neuronal migration disorders, genetics, and epileptogenesis. J Child Neurol. 2005;20:287–99.

Kato M, Dobyns WB. Lissencephaly and the molecular basis of neuronal migration. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:R89–96.

Barkovich AJ, Guerrini R, Kuzniecky RI, Jackson GD, Dobyns WB. A developmental and genetic classification for malformations of cortical development: update 2012. Brain. 2012;135:1348–69.

Di Donato N, Timms AE, Aldinger KA, Mirzaa GM, Bennett JT, Collins S, et al. Analysis of 17 genes detects mutations in 81% of 811 patients with lissencephaly. Genet Med. 2018;20:1354–64.

Kitamura K, Yanazawa M, Sugiyama N, Miura H, Iizuka-Kogo A, Kusaka M, et al. Mutation of ARX causes abnormal development of forebrain and testes in mice and X-linked lissencephaly with abnormal genitalia in humans. Nat Genet. 2002;32:359–69.

Gleeson JG, Allen KM, Fox JW, Lamperti ED, Berkovic S, Scheffer I, et al. Doublecortin, a brain-specific gene mutated in human X-linked lissencephaly and double cortex syndrome, encodes a putative signaling protein. Cell. 1998;92:63–72.

Vissers LE, de Ligt J, Gilissen C, Janssen I, Steehouwer M, de Vries P, et al. A de novo paradigm for mental retardation. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1109–12.

Reiner O, Carrozzo R, Shen Y, Wehnert M, Faustinella F, Dobyns WB, et al. Isolation of a Miller-Dieker lissencephaly gene containing G protein beta-subunit-like repeats. Nature. 1993;364:717–21.

Keays DA, Tian G, Poirier K, Huang GJ, Siebold C, Cleak J, et al. Mutations in alpha-tubulin cause abnormal neuronal migration in mice and lissencephaly in humans. Cell. 2007;128:45–57.

Watanabe K, Nakashima M, Kumada S, Mashimo H, Enokizono M, Yamada K, et al. Identification of two novel de novo TUBB variants in cases with brain malformations: case reports and literature review. J Hum Genet. 2021;66:1193–7.

Fromer M, Moran JL, Chambert K, Banks E, Bergen SE, Ruderfer DM, et al. Discovery and statistical genotyping of copy-number variation from whole-exome sequencing depth. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:597–607.

Uchiyama Y, Yamaguchi D, Iwama K, Miyatake S, Hamanaka K, Tsuchida N, et al. Efficient detection of copy-number variations using exome data: Batch- and sex-based analyses. Hum Mutat. 2021;42:50–65.

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24.

Hiraide T, Shimizu K, Miyamoto S, Aoto K, Nakashima M, Yamaguchi T, et al. Genome sequencing and RNA sequencing of urinary cells reveal an intronic FBN1 variant causing aberrant splicing. J Hum Genet. 2022;67:387–92.

Roller E, Ivakhno S, Lee S, Royce T, Tanner S. Canvas: versatile and scalable detection of copy number variants. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:2375–7.

Chen X, Schulz-Trieglaff O, Shaw R, Barnes B, Schlesinger F, Källberg M, et al. Manta: rapid detection of structural variants and indels for germline and cancer sequencing applications. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:1220–2.

Yu T, Huang X, Dou S, Tang X, Luo S, Theurkauf WE, et al. A benchmark and an algorithm for detecting germline transposon insertions and measuring de novo transposon insertion frequencies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021;49:e44.

Li D, Liu CM, Luo R, Sadakane K, Lam TW. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1674–6.

Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transpl. 2013;48:452–8.

Dobyns WB, Truwit CL, Ross ME, Matsumoto N, Pilz DT, Ledbetter DH, et al. Differences in the gyral pattern distinguish chromosome 17-linked and X-linked lissencephaly. Neurology. 1999;53:270–7.

Abe K, Ando K, Kato M, Saitsu H, Nakashima M, Aoki S, et al. A new case with cortical malformation caused by biallelic variants in LAMC3. Neurol Genet. 2022;8:e680.

Pejaver V, Byrne AB, Feng BJ, Pagel KA, Mooney SD, Karchin R, et al. Calibration of computational tools for missense variant pathogenicity classification and ClinGen recommendations for PP3/BP4 criteria. Am J Hum Genet. 2022;109:2163–77.

Miyata Y, Kosuga M, Kato M, Watanabe K, Nakashima M, Saitsu H, et al. Microlissencephaly caused by a novel compound heterozygous variant in the WDR81 gene: A case report. No To Hattatsu. In press 2025.

Zou D, Wang L, Liao J, Xiao H, Duan J, Zhang T, et al. Genome sequencing of 320 Chinese children with epilepsy: a clinical and molecular study. Brain. 2021;144:3623–34.

Mei D, Lewis R, Parrini E, Lazarou LP, Marini C, Pilz DT, et al. High frequency of genomic deletions–and a duplication–in the LIS1 gene in lissencephaly: implications for molecular diagnosis. J Med Genet. 2008;45:355–61.

Arcot SS, Shaikh TH, Kim J, Bennett L, Alegria-Hartman M, Nelson DO, et al. Sequence diversity and chromosomal distribution of “young” Alu repeats. Gene. 1995;163:273–8.

Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, Nusbaum C, Zody MC, Baldwin J, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921.

Morales ME, White TB, Streva VA, DeFreece CB, Hedges DJ, Deininger PL. The contribution of alu elements to mutagenic DNA double-strand break repair. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005016.

Lobachev KS, Stenger JE, Kozyreva OG, Jurka J, Gordenin DA, Resnick MA. Inverted Alu repeats unstable in yeast are excluded from the human genome. Embo J. 2000;19:3822–30.

Deininger PL, Batzer MA, Hutchison CA 3rd, Edgell MH. Master genes in mammalian repetitive DNA amplification. Trends Genet. 1992;8:307–11.

Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–10.

Nord AS, Lee M, King MC, Walsh T. Accurate and exact CNV identification from targeted high-throughput sequence data. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:184.

Haverfield EV, Whited AJ, Petras KS, Dobyns WB, Das S. Intragenic deletions and duplications of the LIS1 and DCX genes: a major disease-causing mechanism in lissencephaly and subcortical band heterotopia. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:911–8.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patient’s family for their participation in this study. We thank M. Tsujimura, K Shibasaki, M Tanaka, C. Ogawa and A. Kitamoto for their technical assistance. This work was supported in part by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, KAKENHI (Grant number JP 20H03641 and 23H02875 (HS), JP20K08236 (MK) and JP21K06819 (MN)), the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (JP23ek0109549 and 23ek01099674, HS), the Takeda Science Foundation (MN and HS), and HUSM Grant-in-Aid from Hamamatsu University School of Medicine (MN and HS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

About this article

Cite this article

Furukawa, S., Kato, M., Ishiyama, A. et al. Exploring unsolved cases of lissencephaly spectrum: integrating exome and genome sequencing for higher diagnostic yield. J Hum Genet (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s10038-024-01283-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s10038-024-01283-0

- Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.