Abstract

Aerosols have a potentially large effect on climate, particularly through their interactions with clouds, but the magnitude of this effect is highly uncertain. Large volcanic eruptions produce sulfur dioxide, which in turn produces aerosols; these eruptions thus represent a natural experiment through which to quantify aerosol–cloud interactions. Here we show that the massive 2014–2015 fissure eruption in Holuhraun, Iceland, reduced the size of liquid cloud droplets—consistent with expectations—but had no discernible effect on other cloud properties. The reduction in droplet size led to cloud brightening and global-mean radiative forcing of around −0.2 watts per square metre for September to October 2014. Changes in cloud amount or cloud liquid water path, however, were undetectable, indicating that these indirect effects, and cloud systems in general, are well buffered against aerosol changes. This result will reduce uncertainties in future climate projections, because we are now able to reject results from climate models with an excessive liquid-water-path response.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Anthropogenic emissions that affect climate are not just confined to greenhouse gases. Sulfur dioxide and other pollutants form atmospheric aerosols that can scatter and absorb sunlight, and can influence the properties of clouds, modulating the Earth–atmosphere energy balance. Aerosols act as cloud condensation nuclei; an increase in these nuclei translates into a higher number of smaller, more reflective cloud droplets that scatter more sunlight back to space1 (the ‘first indirect effect of aerosols’). Smaller cloud droplets decrease the efficiency of collision-coalescence processes that are pivotal in rain initiation, thus aerosol-influenced clouds may retain more liquid water and extend coverage or lifetime2,3 (the ‘second indirect effect of aerosols’, also known as the ‘cloud lifetime indirect effect’). Aerosols usually co-vary with key environmental variables, making it difficult to disentangle aerosol–cloud effects from meteorological variability4,5,6. Additionally, clouds themselves are complex transient systems subject to dynamical feedbacks (for example, cloud-top entrainment, evaporation and invigoration of convection), which influence cloud response7,8,9,10,11,12. The factors mentioned above present great challenges in evaluating and constraining aerosol–cloud interactions (ACI) in General Circulation Models (GCM)13,14,15,16,17, with some contentious debate surrounding the relative importance of these feedback mechanisms.

Nonetheless, anthropogenic aerosol emissions are thought to cool the Earth via the first and second indirect effects17, but the uncertainty ranges from −1.2 W m−2 to −0.0 W m−2 (90% confidence interval) owing to (i) a lack of characterization of the pre-industrial aerosol state15,18,19, and (ii) parametric and structural errors in models representing cloud responses to aerosol changes16,18,20,21. It is estimated that uncertainty in the pre-industrial state can account for approximately 30% of total ACI uncertainty18,21 while representation of chemistry–aerosol–cloud processes in models is responsible for the remaining 70% uncertainty16,21. Recently, a framework to break down uncertainties in the causal chain from emission to radiative forcing showed that the sources of uncertainty within different GCMs differ greatly16.

Volcanic eruptions provide invaluable natural experiments with which to investigate the role of large-scale aerosol injection in the Earth system22,23,24,25,26. There have been several Icelandic volcanic eruptions over recent years; Eyjafjallajökull erupted in 2010, Grímsvötn in 2011 and Holuhraun in 2014–2015. At its peak, the 2014–2015 eruption at Holuhraun emitted about 120 kilotonnes of sulfur dioxide per day (kt SO2 d−1) into the atmosphere, a rate that is some four times higher than that from all 28 European Union member states or more than one-third of global emission rates. Iceland became in effect a continental-scale pollution source of SO2; SO2 is readily oxidized via gas- and aqueous-phase reactions, producing a massive aerosol plume in a near-pristine environment where clouds should be most susceptible to aerosol concentrations16,18,27.

We build on preliminary observational assessments of the impact of the 2014–2015 eruption at Holuhraun28,29 through an extensive observational analysis, which includes a statistical evaluation of the significance of the observed spatial distribution of the cloud perturbations, to untangle the aerosol and meteorological effects. We then assess the simulations from a range of different climate models, and compare their performance against available observations. Last, we show that observations of a volcanic plume (Mt Kilauea, Hawaii) in an entirely different meteorological regime reveal similar overall effects.

Effect of the eruption on clouds

Following the lifecycle of sulfur from emission, our initial analysis concentrates on the coherence of SO2 detected by the Infrared Atmospheric Sounding Interferometer (IASI) sensor (Supplementary Methods, section M1) with that predicted by the HadGEM3 GCM that is constrained by observed temperatures and winds (that is, ‘nudged’, Supplementary Methods, section M2). IASI retrievals use the discrete spectral absorption structure of SO2 to determine concentrations30. Comparisons of IASI SO2 observations from explosive volcanic eruptions against model simulations have proven valuable in the past31,32. The processing procedure for quantitative comparison between IASI and HadGEM3 data uses only data that are spatially and temporally coherent (Supplementary Methods, section M3).

There is considerable uncertainty in the quantitative emission of SO2 from the 2014–2015 eruption at Holuhraun. A previous study28 assumed a constant emission rate of 40 kt SO2 d−1 on the basis of initial estimates of degassing. As our standard scenario (STAN) we use an empirical relationship between degassed sulfur, TiO2/FeO ratios and lava production derived from Icelandic basaltic flood lava eruptions33, which suggests markedly higher emissions during the early phase of the eruption in September, but we also investigate a simulation where a constant 40 kt SO2 d−1 is released (40KT scenario). The model simulations and IASI retrievals of column SO2 are shown in Fig. 1 (40KT emission scenario shown in Supplementary Discussion, section S1).

Maps show spatial distribution of SO2 column loading within the plume produced by the 2014–2015 eruption at Holuhraun; time increases from top to bottom. Left, processed data from HadGEM3 masked using positive detections of SO2 from IASI and spatially and temporally coherent plume data from HadGEM3. Right, processed data from IASI re-gridded onto the regular HadGEM3 grid. Column loadings (‘SO2 columnar density’, colour coded) are expressed in Dobson units (DU), with 1 DU equivalent to approximately 0.0285 g SO2 m−2. For each subpanel, ‘avg’ represents the average columnar density of SO2 within the plume over the week indicated, with week 1 corresponding to 1–7 September.

The distribution and the magnitude of the column loading of SO2 detected by IASI are similar to those derived from HadGEM3, showing that the GCM nudging scheme and the assumed altitude of the emissions in the STAN scenario (surface to 3 km) reproduces the week to week spatial variability and magnitude of observed column SO2 (Supplementary Video 1).

While the spatial distribution of sulfate aerosol optical depth (AOD) caused by the eruption can be determined easily in the model (Supplementary Fig. 2.1), detection of the aerosol plume over the North Atlantic Ocean in the MODIS data is hampered by the mutual exclusivity of aerosol and cloud retrievals. The predominance of cloudy scenes makes accurate detection of the aerosol plume in monthly mean MODIS data extremely challenging (Supplementary Discussion, section S2). Nonetheless, despite lacking observations of AOD, we can look for evidence of perturbations caused by aerosols on cloud properties. We examine the perturbation to retrieved cloud-top droplet effective radius (reff) in September and October 2014 using Collection 051 monthly mean data from MODIS AQUA (MYD08, Supplementary Methods, section M4) over the period 2002–2014. MODIS AQUA data are not subject to the degradation in performance of the sensors at visible wavelengths that has recently been documented for the MODIS TERRA34 sensor (Supplementary Discussion, section S3). We present a summary of the change in reff, that is, Δreff, for October 2014 compared to the long term 2002–2013 mean in Fig. 2a. A full analysis of the year-to-year variability in Δreff is presented in Supplementary Discussion, section S4.

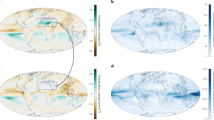

a–d, The mean changes (‘anomalies’) in cloud droplet effective radius, Δreff (in μm; a), and in liquid water path, ΔLWP (in g m−2; c), with corresponding zonal means; also shown are the probability distributions of absolute cloud droplet effective radius (in μm; b) and liquid water path (in g m−2; d) for the year 2014 (blue) and the 2002–2013 mean (green). Changes correspond to the deviation from the 2002–2013 mean. Stippling in a and c represents areas of perturbation significant at 95% confidence on the basis of a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Grey shading in the zonal means represents the standard deviation over 2002–2013 over the area shown. The area mean represents the spatial average of anomalies over the domain of analysis.

There is clear evidence of a signal in Δreff in October (Fig. 2a) and September (Supplementary Fig. 5.1a). Pixels that are statistically significantly different from the 2002–2013 climatological mean at 95% confidence occur over the entire breadth of the North Atlantic Ocean. The spatial distribution of Δreff is governed by the prevailing wind conditions that advect the volcanic plume and are quantitatively similar to those noted in Collection 006 MODIS data29.

Figure 3a shows the corresponding Δreff derived from the model in October (for September, see Supplementary Fig. 5.2a). The observations and modelling show obvious similarities in spatial distribution. In addition to the spatial coherence in Δreff, the changes in the model of −1.21 μm (September) and −0.68 μm (October) are within 30% of MODIS Δreff of −0.98 μm (September) and −0.98 μm (October) for the domain shown in Fig. 2.

a–d, As Fig. 2 except that in b and d the data for 2014 are shown including (blue) or excluding (gold) the Holuhraun emissions.

There are similarities between the MODIS and HadGEM3 probability distribution functions (Figs 2b and 3b) with a shift to smaller reff for the year of the eruption. Almost all high values of reff (that is, reff ≳ 16 μm for MODIS and reff ≳ 11 μm for HadGEM3) are absent in 2014, suggesting that clouds with high reff are entirely absent from the domain in both the observations and the model. There are obvious discrepancies in the absolute magnitude of reff between MODIS and HadGEM3. MODIS retrievals of reff from the MYD06 product in liquid water cloud regimes have been shown to be markedly larger than those derived from other satellite sensor products, mainly because of the algorithm’s use of a different primary spectral channel relative to other products35,36. Nevertheless, Δreff is in encouraging agreement as this quantity, along with changes in cloud liquid water path (LWP), needs to be accurately represented if ACI are to be better quantified. As with reff, there are similarities between MODIS and HadGEM3 for ΔLWP (Figs 2c, d and 3c, d), however, evidence of a clear signal due to the volcano is neither observed or modelled. Additionally, we found that perturbations in the monthly mean cloud fraction from MODIS are negligible, both in September and October as previously reported29.

It is incumbent on any study attributing Δreff to volcanic emissions to prove the causality beyond reasonable doubt—that is, that the changes are not due to natural meteorological variability. The meteorological analyses in Supplementary Discussion, section S6 suggest that, while in September 2014 the southern part of the spatial domain shown in Fig. 2 is somewhat influenced by anomalous easterlies bringing pollution from the European continent over the easternmost Atlantic Ocean and hence influencing reff, the perturbations to reff during October 2014 are entirely of volcanic origin.

MODIS and HadGEM3 show a similar spatial distribution and magnitude for the perturbation in cloud droplet number concentration (ΔNd) for October, but a smaller ΔNd in MODIS than in HadGEM3 for September 2014 (Supplementary Discussion, section S7.2). Once reff is reduced, the autoconversion process whereby cloud droplets grow to sufficient size to form precipitation may be inhibited, leading to clouds with increased LWP (ref. 3). The cloud optical depth, τcloud, is related to reff, LWP and the density of water (ρ) by the approximation

We use HadGEM3 to assess the detectability of perturbations in the presence of natural variability. Two different methods are pursued using the nudged model; first, assessing model simulations with and without the emissions from the eruption for the year 2014 (referred to as HOL2014 − NO_HOL2014), and second, assessing model simulations including emissions from Holuhraun for 2014 against simulations for 2002–2013 (HOL2014 − NO_HOL2002–2013). Whereas the former method allows the ‘cleanest’ assessment of the effects of the eruption (as the meteorology is effectively identical and meteorological variability is removed), the second method allows assessment of the statistical significance against the natural meteorological variability. This provides an assessment that is directly comparable to observations and can be used to effectively isolate signal from noise37 (Supplementary Discussion, section S7).

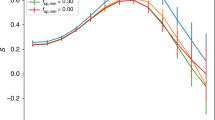

Figure 4 shows that ΔAOD, ΔNd and Δreff are statistically significant at 95% confidence across the majority of latitudes. The fact that the simulations from HOL2014 − NO_HOL2014 and HOL2014 − NO_HOL2002–2013 are similar for these variables again indicates that the effect of natural meteorological variability on these variables is small (that is, NO_HOL2014 ≈ NO_HOL2002–2013). For ΔLWP, no statistically significant changes are evident at either 95% or 67% confidence, suggesting that meteorological variability provides a far stronger control on cloud LWP than aerosol (Supplementary Discussion, section S7.3). With ΔLWP being due to meteorological noise, Δτcloud is driven by Δreff and Fig. 4e suggests that the perturbations to τcloud north of around 67° N (57° N), which are significant at the 95% (67%) confidence level, are due to the 2014–2015 Holuhraun eruption. Our simulations suggest that top-of-atmosphere (TOA) changes in short-wave radiation (ΔTOASW) are unlikely to be detectable at 95% or even 67% confidence when compared to natural variability. More details supporting this assertion are given in Supplementary Discussion, section S7.5, in which satellite observations of the Earth’s radiation budget are examined.

a–f, Shown are perturbations for sulfate aerosol optical depth, AOD (a), cloud droplet number concentration, Nd (b), cloud droplet effective radius, reff (c), cloud liquid water path, LWP (d), cloud optical depth, τcloud (e), and top-of-atmosphere net short-wave radiation, TOASW (f). Zonal means are shown for the 44° N–80° N, 60° W–30° E analysis region. The shaded regions represent the natural variability in the simulations from 2002–2013. Values outside of the light grey (respectively dark grey, bottom row) shaded regions represent perturbations significant at the 95% (respectively 67%) confidence level on the basis of a two-tailed Student’s t-test. Red lines represent HOL2014 minus NO_HOL2014 and blue lines represent HOL2014 minus NO_HOL2002–2013 (see text).

We have shown that HadGEM3 is capable of reproducing observations of ACI with a reasonable representation of the perturbation to reff but minimal perturbation to LWP. To demonstrate the practical value of the study, we repeat the simulations with other models. First, we use HadGEM3 but employ the older single-moment CLASSIC38 aerosol scheme instead of the new two-moment UKCA/GLOMAP-mode scheme39. We also perform calculations with the NCAR Community Atmosphere Model28 (CAM5-NCAR) and the atmospheric component of an intermediate version of the Norwegian Earth System Model40 (CAM5-Oslo), driven using nominally the same emissions and plume-top height. CAM5-NCAR has been used previously in free-running mode to provide an initial estimate of the radiative forcing of the 2014–2015 Holuhraun eruption28, but as in the HadGEM3 simulations we run CAM5-NCAR and CAM5-Oslo in nudged mode to simulate the meteorology during the eruption as closely as possible. Figure 5 shows a comparison of Δreff and ΔLWP derived from HOL2014 − NO_HOL2014 simulations from HadGEM3, HadGEM3-CLASSIC, CAM5-NCAR, CAM5-Oslo and MODIS for October. We chose October as the contribution from continental Europe pollution to cloud property anomalies has been shown to be small (Supplementary Discussion, sections S4, S6 and S7; Supplementary Discussion, section S8 shows the effects on cloud properties in September).

Left column shows colour-coded Δreff (in μm) and right column colour-coded ΔLWP (in g m−2): within each column the main panel shows the geographical distribution, and the smaller panel at right shows the zonal mean anomaly in reff and in LWP, with blue areas representing negative values and red areas positive values. Top to bottom, data determined from HadGEM3 using the two-moment UKCA/GLOMAP-mode aerosol scheme, from HadGEM3 using the single moment CLASSIC aerosol scheme, from CAM5-NCAR, from CAM5-Oslo, and from AQUA MODIS. Note that MODIS anomalies (bottom row) show the effects of aerosols plus the meteorological variability (2014 minus the 2002–2013 mean), whereas the model simulations (top four rows) show the effect of aerosols only (2014 with eruption minus 2014 without eruption; see Supplementary Discussion, section S7). The area mean represents the spatial average of anomalies over the domain of analysis. Small differences in the area mean values in the bottom two panels compared to Fig. 2a and c are due to the reprocessing of data onto a common grid.

It is immediately apparent from the first column of Fig. 5 that HadGEM3 using UKCA, CAM5-NCAR and CAM5-Oslo are able to accurately model the effect on Δreff, whereas HadGEM3-CLASSIC produces an effect that is too strong when compared to the MODIS observations owing to the single moment nature of the aerosol scheme (Supplementary Discussion, section S9).For ΔLWP, as we have seen from the multi-year analysis of MODIS (Supplementary Fig. 7.3), the meteorological variability is the controlling factor. Even with meteorological variability suppressed in these HOL2014 − NO_HOL2014 results, HadGEM3 using UKCA shows only a very limited increase in LWP (Fig. 5f), HadGEM3-CLASSIC and CAM5-Oslo show a progressively more significant response, whereas CAM5-NCAR shows a much larger response (Fig. 5h).

It is useful to examine the influence of the eruption on precipitation in both observations and models using a similar analysis (Supplementary Discussion, section S10). We observe that there is little effect on precipitation, indicating that the cloud system readjusts to a new equilibrium with little effect on either LWP or precipitation. The larger response in CAM5-NCAR (ΔLWP > 16 g m−2) is not supported by the MODIS observations where the 2002–2013 domain-mean standard deviation in ΔLWP is about 4.5 g m−2. Thus, we are able to use the eruption to evaluate the models: HadGEM3 using UKCA and CAM5-Oslo perform in a manner consistent with the MODIS observations, whereas HadGEM3-CLASSIC and CAM5-NCAR do not. Moreover, the fact that changes in LWP are not detectable above natural variability suggests that ACI beyond the effect on reff are small (that is, net second indirect effects are small).

The effective radiative forcing (ERF) from the event may be estimated from the difference between the TOA net irradiances from simulations including and excluding the volcanic emissions. The global ERF from HadGEM3 over the September–October 2014 period is estimated at −0.21 W m−2. Tests using an offline version of the radiation code reveal that the presence of overlying ice cloud weakens the ERF by approximately 20% (Supplementary Discussion, section S11).

We also investigate whether a fissure eruption of this magnitude could have a greater radiative impact if the timing or location of the eruption was different (Supplementary Discussion, section S12). Our simulations suggest that for contrasting scenarios the global ERF would: (i) strengthen to −0.61 W m−2 (+194%) if the eruption commenced at the beginning of June; (ii) strengthen to −0.49 W m−2 (+140%) if the eruption had occurred in an area of South America where it could affect clouds in a stratocumulus-dominated regime; and (iii) strengthen to −0.32 W m−2 (+55%) if the eruption had occurred in pre-industrial times when the background concentrations of aerosols was reduced18. The last indicates that the climatic impact of fissure eruptions such as Laki41 in 1783–1784 would not have been as large if it had occurred in the present day.

Many studies9,11,42,43 suggest that cloud adjustments may be dependent upon meteorological regime, so we investigated whether the cloud LWP invariance observed near Holuhraun is simply a special case. We have reproduced the cloud regime analysis derived from satellite measurements44. We find that, when examining the 2014–2015 eruption at Holuhraun, we are far from examining a meteorological ‘special case’, in fact rather the opposite (Supplementary Discussion, section S13); we are examining a region that contains the whole spectrum of liquid-dominated cloud regimes and deducing that, overall, the effect on LWP is minimal.

To further support our conclusion, we report results from a different event (Mount Kilauea, Hawaii, Supplementary Discussion, section S14), in which the degassing rate significantly increased during June–August 2008. The outflow of the plume affected the surrounding trade-wind maritime cumuli24,45,46 and the short-wave reflectance of the plume increased, although different causal interpretations were made24,46. We found that LWP does not vary in the MODIS monthly retrievals (Supplementary Discussion, section S14), consistent with previous findings for the AMSR-E data46, which again suggests LWP insensitivity, this time in the trade-wind cumulus regime. Therefore, for a very different meteorological environment dominated by very different cloud regimes, similar conclusions emerge.

Discussion and conclusion

The 2014–2015 eruption at Holuhraun presents a unique opportunity to investigate continental-scale aerosol–cloud climatic effects. Using synergistic observations and models driven by an empirical estimate of SO2 emissions33, we have simulated spatial distributions of SO2 that compare favourably with satellite observations. The HadGEM3 model is able to predict an impact from ACI of similar magnitude to the signal found in the MODIS data. Our analysis further highlights that cloud properties are largely unaffected by the eruption beyond the effect on reff.

We repeated the Holuhraun simulations with three additional GCMs, and showed that HadGEM3 using UKCA, CAM5-NCAR and CAM5-Oslo are able to capture the magnitude of the observed effects on reff despite the lack of explicit representation of processes such as sub-cloud updraft velocities and entrainment: this enhances our confidence in the ability of GCMs to predict the first indirect effect of aerosols. However, in line with recent work16, we found that our modelled responses in the cloud LWP differ markedly from one another. The fact that cloud adjustments via LWP are not identified in the observations of the 2014–2015 eruption at Holuhraun indicates that clouds are buffered against LWP changes9,10,12, providing evidence that models with a low LWP response display a more convincing behaviour. These findings have wide scientific relevance in the field of climate modelling as, in terms of climate forcing, they suggest that aerosol second indirect effects appear small and that climate models with a significant LWP feedback need reassessment15,16,47.

Despite such massive emissions at Holuhraun and large anomalies in reff, we estimate a moderate global-mean radiative forcing of −0.21 ± 0.08 W m−2 (±1 s.d., Supplementary Discussion, section S15) for September–October 2014, which equates to a global annual mean effective radiative forcing of −0.035 ± 0.013 W m−2 (±1 s.d.) assuming that a forcing only occurs in September and October 2014. Global emissions of anthropogenic SO2 currently total around 100 Tg SO2 yr−1, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change17,47 suggests a best estimate for the aerosol forcing of −0.9 W m−2, yielding a forcing efficiency of −0.009 W m−2 per Tg SO2. The emissions for September and October 2014 total approximately 4 Tg SO2, thus the global annual mean radiative forcing efficiency for the 2014–2015 eruption at Holuhraun is −0.0088 ± 0.0024 W m−2 per Tg SO2 (±1 s.d.). The similarity is remarkable, but may be by chance given the modelled sensitivity to emission location and time (Supplementary Discussion, section S12).

Our study is not without caveats, given that the observations themselves are uncertain owing to the limitations of satellite retrievals. The modelling is not completely constrained owing to the lack of detailed in situ observations of, for example, the background aerosol concentrations and plume height. We cannot rule out that models showing small LWP sensitivity to aerosol emission behave as they do because they lack the resolution to represent fine-scale dynamical feedbacks9,12. Further high-resolution modelling of the 2014–2015 Holuhraun eruption is necessary to evaluate more thoroughly how processes such as autoconversion or droplet evaporation play a part in buffering the aerosol effect9,12,48,49. Bringing many of the different global models together and inter-comparing results of Holuhraun simulations shows merit as a way to provide a traceable route for reducing the uncertainty in future climate projections.

Change history

04 October 2017

Nature 546, 485–491 (2017); doi:10.1038/nature22974 Owing to a production error, the area means in Fig. 3a appeared incorrectly as −0.676 μm instead of −0.68 μm, and in Fig. 3c as –0.745 g m–2, instead of +0.75 g m−2. We also note a mistake in our estimate of the effective radiative forcing (ERF) for the experiment that considers a fissure eruption in June–July.

References

Twomey, S. The influence of pollution on the shortwave albedo of clouds. J. Atmos. Sci. 34, 1149–1152 (1977)

Albrecht, B. A. Aerosols, cloud microphysics, and fractional cloudiness. Science 245, 1227–1230 (1989)

Haywood, J. M. & Boucher, O. Estimates of the direct and indirect radiative forcing due to tropospheric aerosols: a review. Rev. Geophys. 38, 513–543 (2000)

Lohmann, U., Koren, I. & Kaufman, Y. J. Disentangling the role of microphysical and dynamical effects in determining cloud properties over the Atlantic. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L09802 (2006)

Mauger, G. S. & Norris, J. R. Meteorological bias in satellite estimates of aerosol-cloud relationships. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L16824 (2007)

Gryspeerdt, E., Quaas, J. & Bellouin, N. Constraining the aerosol influence on cloud fraction. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 3566–3583 (2016)

Ackerman, A. S. et al. The impact of humidity above stratiform clouds on indirect climate forcing. Nature 432, 1014–1017 (2004)

Sandu, I., Brenguier, J. L., Geoffroy, O., Thouron, O. & Masson, V. Aerosol impacts on the diurnal cycle of marine stratocumulus. J. Atmos. Sci. 65, 2705–2718 (2008)

Stevens, B. & Feingold, G. Untangling aerosol effects on clouds and precipitation in a buffered system. Nature 461, 607–613 (2009)

Seifert, A., Köhler, C. & Beheng, K. D. Aerosol-cloud-precipitation effects over Germany as simulated by a convective-scale numerical weather prediction model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 709–725 (2012)

Lebo, Z. J. & Feingold, G. On the relationship between responses in cloud water and precipitation to changes in aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 11817–11831 (2014)

Seifert, A., Heus, T., Pincus, R. & Stevens, B. Large-eddy simulation of the transient and near-equilibrium behaviour of precipitating shallow convection. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 7, 1918–1937 (2015)

Quaas, J. et al. Aerosol indirect effects — general circulation model intercomparison and evaluation with satellite data. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 8697–8717 (2009)

Penner, J. E., Xu, L. & Wang, M. H. Satellite methods underestimate indirect climate forcing by aerosols. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 13404–13408 (2011)

Stevens, B. Rethinking the lower bound on aerosol radiative forcing. J. Clim. 28, 4794–4819 (2015)

Ghan, S. et al. Challenges in constraining anthropogenic aerosol effects on cloud radiative forcing using present-day spatiotemporal variability. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 5804–5811 (2016)

Boucher, O . et al. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) Ch. 7 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013)

Carslaw, K. S. et al. Large contribution of natural aerosols to uncertainty in indirect forcing. Nature 503, 67–71 (2013)

Hamilton, D. S. et al. Occurrence of pristine aerosol environments on a polluted planet. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 18466–18471 (2014)

Lohmann, U. et al. Total aerosol effect: radiative forcing or radiative flux perturbation? Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 3235–3246 (2010)

Gettelman, A. Putting the clouds back in aerosol-cloud interactions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 12397–12411 (2015)

McCormick, M. P., Thomason, L. W. & Trepte, C. R. Atmospheric effects of the Mt Pinatubo eruption. Nature 373, 399–404 (1995)

Gassó, S. Satellite observations of the impact of weak volcanic activity on marine clouds. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113, D14S19 (2008)

Yuan, T., Remer, L. A. & Yu, H. Microphysical, macrophysical and radiative signatures of volcanic aerosols in trade wind cumulus observed by the A-Train. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 7119–7132 (2011)

Schmidt, A. et al. Importance of tropospheric volcanic aerosol for indirect radiative forcing of climate. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 7321–7339 (2012)

Haywood, J. M., Jones, A. & Jones, G. S. The impact of volcanic eruptions in the period 2000–2013 on global mean temperature trends evaluated in the HadGEM2-ES climate model. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 15, 92–96 (2014)

Penner, J. E., Zhou, C. & Xu, L. Consistent estimates from satellites and models for the first aerosol indirect forcing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L13810 (2012)

Gettelman, A., Schmidt, A. & Kristjánsson, J.-E. Icelandic volcanic emissions and climate. Nat. Geosci. 8, 243 (2015)

McCoy, D. T. & Hartmann, D. L. Observations of a substantial cloud-aerosol indirect effect during the 2014–2015 Bárðarbunga-Veiðivötn fissure eruption in Iceland. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 10409–10414 (2015)

Clarisse, L. et al. Tracking and quantifying volcanic SO2 with IASI, the September 2007 eruption at Jebel at Tair. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 8, 7723–7734 (2008)

Haywood, J. M. et al. Observations of the eruption of the Sarychev volcano and simulations using the HadGEM2 climate model. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 115, D21212 (2010)

Schmidt, A. et al. Satellite detection, long-range transport, and air quality impacts of volcanic sulfur dioxide from the 2014–2015 flood lava eruption at Bárðarbunga (Iceland). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 9739–9757 (2015)

Thordarson, T., Self, S., Miller, D. J., Larsen, G. & Vilmundardóttir, E. G. Sulphur release from flood lava eruptions in the Veidivötn, Grímsvötn and Katla volcanic systems, Iceland. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 213, 103–121 (2003)

Polashenski, C. M. et al. Neither dust nor black carbon causing apparent albedo decline in Greenland’s dry snow zone: implications for MODIS C5 surface reflectance. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 9319–9327 (2015)

Platnick, S. et al. MODIS Atmosphere L2 Cloud Product (06_L2) (NASA MODIS Adaptive Processing System, Goddard Space Flight Center, 2015); available at http://dx.doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MOD06_L2.006

Zhang, Z. & Platnick, S. An assessment of differences between cloud effective particle radius retrievals for marine water clouds from three MODIS spectral bands. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 116, D20215 (2011)

Stevens, B. & Brenguier, J.-L. in Clouds in the Perturbed Climate System: Their Relationship to Energy Balance, Atmospheric Dynamics, and Precipitation (eds Heintzenberg, J . & Charlson, R. J. ) Ch. 8 (Strüngmann Forum Report, Vol. 2, MIT Press, 2009 ).

Bellouin, N. et al. Aerosol forcing in the Climate Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5) simulations by HadGEM2-ES and the role of ammonium nitrate. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 116, D20206 (2011)

Dhomse, S. S. et al. Aerosol microphysics simulations of the Mt. Pinatubo eruption with the UM-UKCA composition-climate model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 11221–11246 (2014)

Kirkevåg, A. et al. Aerosol-climate interactions in the Norwegian Earth System Model — NorESM1-M. Geosci. Model Dev. 6, 207–244 (2013)

Schmidt, A. et al. The impact of the 1783–1784 AD Laki eruption on global aerosol formation processes and cloud condensation nuclei. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 6025–6041 (2010)

Zhang, S. et al. On the characteristics of aerosol indirect effect based on dynamic regimes in global climate models. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 2765–2783 (2016)

Michibata, T., Suzuki, K., Sato, Y. & Takemura, T. The source of discrepancies in aerosol–cloud–precipitation interactions between GCM and A-Train retrievals. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 15413–15424 (2016)

Oreopoulos, L., Cho, N., Lee, D. & Kato, S. Radiative effects of global MODIS cloud regimes. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 121, 2299–2317 (2016)

Eguchi, K. et al. Modulation of cloud droplets and radiation over the North Pacific by sulfate aerosol erupted from Mount Kilauea. Sci. Online Lett. Atmos. 7, 77–80 (2011)

Mace, G. G. & Abernathy, A. C. Observational evidence for aerosol invigoration in shallow cumulus downstream of Mount Kilauea. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 2981–2988 (2016)

Myhre, G . et al. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) Ch. 8 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013)

Golaz, J.-C., Horowitz, L. W. & Levy, H. Cloud tuning in a coupled climate model: impact on 20th century warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 2246–2251 (2013)

Zhou, C. & Penner, J. E. Why do general circulation models overestimate the aerosol cloud lifetime effect? A case study comparing CAM5 and a CRM. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 21–29 (2017)

Acknowledgements

J.M.H., A.J., M.D., B.T.J., C.E.J., J.R.K. and F.M.O.C. were supported by the Joint UK BEIS/Defra Met Office Hadley Centre Climate Programme (GA01101). The National Center for Atmospheric Research is sponsored by the US National Science Foundation. S.B. and L.C. are respectively Research Fellow and Research Associate funded by FRS-FNRS. P.S. acknowledges support from the European Research Council (ERC) project ACCLAIM (grant agreement FP7-280025). J.M.H., F.F.M., D.G.P. and P.S. were part-funded by the UK Natural Environment Research Council project ACID-PRUF (NE/I020148/1). A.S. was funded by an Academic Research Fellowship from the University of Leeds and NERC urgency grant NE/M021130/1 (‘The source and longevity of sulphur in an Icelandic flood basalt eruption plume’). R.A. was supported by the NERC SMURPHS project NE/N006054/1. G.W.M. was funded by the National Centre for Atmospheric Science, one of the UK Natural Environment Research Council’s research centres. D.P.G. is funded by the School of Earth and Environment at the University of Leeds. G.W.M. and S.D. acknowledge additional EU funding from the ERC under the FP7 consortium project MACC-II (grant agreement 283576) and Horizon 2020 project MACC-III (grant agreement 633080). G.W.M., K.S.C. and D.G. were also supported via the Leeds-Met Office Academic Partnership (ASCI project). The work done with CAM5-Oslo is supported by the Research Council of Norway through the EVA project (grant 229771), NOTUR project nn2345k and NorStore project ns2345k. We thank the following researchers who have contributed to the development version of CAM5-Oslo used in this study: K. Alterskjær, A. Grini, M. Hummel, T. Iversen, A. Kirkevåg, D. Olivié, M. Schulz and Ø. Seland. The AQUA/MODIS MYD08 L3 Global 1 Deg. data set was acquired from the Level-1 and Atmosphere Archive and Distribution System (LAADS) Distributed Active Archive Center (DAAC), located in the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland (https://ladsweb.nascom.nasa.gov/). This work is dedicated to the memory of co-author Jón Egill Kristjánsson who died in a climbing accident in Norway.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.F.M. (text, processing and analysis of the satellite data and the model results), J.M.H. (text, analysis of the satellite data and the model results, radiative transfer calculations), A.J., A.G., I.H.H.K. and J.E.K. (model runs), R.A. (processing of the CERES data and contribution to the text), L.C. and S.B. (processing of the IASI data and contribution to the text), L.O., N.C. and D.L. (MODIS cloud regimes), D.P.G. (estimate of CDNC from MODIS data), T.T. and M.E.H. (provided emission estimates for the 2014–2015 eruption at Holuhraun), A.J., N.B., O.B., K.S.C., S.D., G.W.M., A.S., H.C., M.D., A.A.H., B.T.J., C.E.J., F.M.O.C., D.G.P. and P.S. (contribution to the development of UKCA), and G.M., S.P., G.L.S., H.T. and J.R.K. (discussion contributing to text and/or help with the MODIS data).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Reviewer Information Nature thanks R. Allen, M. Schulz, B. Toon and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Methods, a Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Tables, Supplementary Figures, Code Availability, Data availability and Supplementary References. (PDF 30398 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Malavelle, F., Haywood, J., Jones, A. et al. Strong constraints on aerosol–cloud interactions from volcanic eruptions. Nature 546, 485–491 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature22974

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature22974

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Substantial cooling effect from aerosol-induced increase in tropical marine cloud cover

Nature Geoscience (2024)

-

Multifaceted aerosol effects on precipitation

Nature Geoscience (2024)

-

Phases in fine volcanic ash

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

“Cooling credits” are not a viable climate solution

Climatic Change (2023)

-

Aerosol Load-Cloud Cover Correlation: A Potential Clue for the Investigation of Aerosol Indirect Impact on Climate of Europe and Africa

Aerosol Science and Engineering (2023)