Abstract

For centuries, biogeographers have examined the factors that produce patterns of biodiversity across regions. The study of islands has proved particularly fruitful and has led to the theory that geographic area and isolation influence species colonization, extinction and speciation such that larger islands have more species and isolated islands have fewer species (that is, positive species–area and negative species–isolation relationships)1,2,3,4. However, experimental tests of this theory have been limited, owing to the difficulty in experimental manipulation of islands at the scales at which speciation and long-distance colonization are relevant5. Here we have used the human-aided transport of exotic anole lizards among Caribbean islands as such a test at an appropriate scale. In accord with theory, as anole colonizations have increased, islands impoverished in native species have gained the most exotic species, the past influence of speciation on island biogeography has been obscured, and the species–area relationship has strengthened while the species–isolation relationship has weakened. Moreover, anole biogeography increasingly reflects anthropogenic rather than geographic processes. Unlike the island biogeography of the past that was determined by geographic area and isolation, in the Anthropocene—an epoch proposed for the present time interval—island biogeography is dominated by the economic isolation of human populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The number of species (that is, richness) on islands is theorized to be a function of colonization and in situ speciation that add species, and extinction that subtracts them1,2,3,4,5,6. Larger and less-isolated islands have lower extinction and higher colonization compared to smaller and more-isolated islands. Larger islands have more in situ speciation than smaller islands because they have a greater diversity of habitat types and offer more opportunities for allopatric divergence7,8, while isolated islands have fewer and more closely related species because they are infrequently colonized9,10. Island area is thought to set the maximum richness islands can contain (that is, equilibrium saturation points1), while isolation and in situ speciation influence how close islands are to saturation. Together, these processes are presumed to cause the positive species–area and negative species–isolation relationships (SARs and SIRs) ubiquitous across islands.

Tests of this theory are lacking owing to limits in the scale at which experimental manipulation is possible5. For example, the most comprehensive experiment was an arthropod defaunation and recovery manipulation of six small, un-isolated islands (maximum area <0.003 ha; maximum interisland distance <1.2 km)11. Other tests have monitored diversity recoveries from natural catastrophes that wiped out existing species (for example, volcanic eruptions12). These studies demonstrated that colonization and extinction can balance each other to determine species richness—although this equilibrium may take a long time, if ever, to achieve4,13—and that area and extinction rate are negatively correlated14. Other predicted relationships have not been experimentally investigated because all previous tests were on few islands of small size and limited isolation where the effects of speciation and long-distance colonization could not be assessed.

Here, we illustrate how the spread of exotic species experimentally tests island biogeography theory15,16,17. In the past, changes to the species richness of major islands (that is, those large and isolated enough to have speciation and infrequent colonizations) have occurred on timescales precluding direct human observation and testing of theoretical predictions. This is no longer the case today. For many insular groups, island richness is increasing as the number of exotic species establishing surpasses the number of native species lost18.

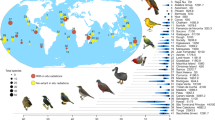

Caribbean Anolis lizards are one such group. Until recently, each Caribbean island bank—shallow areas that connect islands—housed endemic clades of anoles (Fig. 1, Extended Data Fig. 1)19. This high endemicity resulted because over-water dispersal is naturally perilous for anoles, making natural long-distance colonization rare and allopatric speciation common even among neighbouring banks. No anole has gone extinct except possibly one (Anolis roosevelti)20. In contrast, 34 populations comprising 18 species have established on a Caribbean island far from their native bank, increasing mean bank richness from 4.72 (2.06 s.e.m.) to 5.41 (1.91; P ≪ 0.001, Fig. 1, Extended Data Table 1). If the tenets of island biogeography theory are valid, then this human-mediated increased colonization will predictably alter anole biogeography and richness relationships. Here we test three predictions: exotic anoles have mostly established on impoverished banks, increased anole colonizations have diminished the past signal of speciation on bank richness, and the anole SAR has strengthened while the anole SIR has weakened.

Have exotic anoles established on banks furthest from their area-set saturation points? Banks impoverished in native anoles should provide the most opportunity for new species establishment. We estimated bank saturation as the residuals from a log-linear regression of native richness on area (that is, lower residuals suggest impoverished banks, Extended Data Fig. 2). As predicted, exotic anoles have established on the most impoverished banks (coefficient of exotic richness on saturation: –0.422 ± 0.126, P = 0.002)—a result also robust to an alternative metric based on a direct estimate of the anole saturation curve (−0.409 ± 0.126, P = 0.003, Extended Data Table 2).

Has increased colonization obscured the past effect of speciation on anole biogeography? Speciation is responsible for two main biogeographic patterns in anoles. First, because an isolated island is more likely to contain species descended from speciation of a few colonists from the same source area rather than multiple colonists from multiple source areas, which is more likely for proximate islands10, negative phylogenetic diversity–isolation relationships (PDIRs) are expected where the most isolated islands contain small numbers of closely related species. Such a relationship previously existed for Caribbean anoles. Anoles found on the same bank were more closely related to each other than expected if species randomly colonized banks regardless of isolation (Fig. 1; mean standardized effect: –8.08, P ≪ 0.001, indicating strong phylogenetic underdispersion)21, and as a result of this non-random colonization, the PDIR was strongly negative (past PDIR coefficient: –0.734 ± 0.196, P = 0.002, Extended Data Fig. 3). In the present day, anole assemblages are more phylogenetically random (increase in mean standardized effect: 3.02, P ≪ 0.001) because exotic species can colonize isolated banks from across the Caribbean (compare native and exotic distributions in Fig. 1)22; consequently the anole PDIR has been eliminated (present PDIR coefficient: –0.520 ± 0.245, P > 0.05; Extended Data Fig. 3).

Second, in situ speciation is expected to be a nonlinear function of area, stemming from a threshold area below which speciation does not occur6,7,8. This effect causes two-part SARs in which species richness rises modestly with area up to the threshold, and then increases dramatically. In the past, the anole SAR exhibited this nonlinearity (Fig. 2a), but the pattern is now gone. The present-day SAR is linear (P < 0.001) because the area relationship of banks without in situ speciation has become similar to the area relationship of banks with in situ speciation (Fig. 2b). This homogenization of relationships is expected because banks that lacked in situ speciation (Extended Data Fig. 1) were impoverished in species, especially banks just below the breakpoint in Fig. 2a (P = 0.007, Extended Data Table 3).

a, The past SAR was nonlinear and best fitted by a regression with two slopes and a breakpoint (*, 3.579 [CI95%, 3.337–3.822], P ≪ 0.001)6. In all panels, solid black lines indicate regression fits across all banks and coloured lines are regressions of banks with (red) or without (blue) in situ speciation. b, Colonization of exotic anoles has eliminated the two-part SAR. Solid symbols are banks with exotics and the y-axis plots loge(species richness). c, In the past, there was a strong SIR across all banks. ‘Isolation’ is the mean of three orthogonal isolation metrics (Table 1, Extended Data Table 4). d, Exotic colonization has reduced the strength of the SIR by eliminating the SIR of banks without in situ speciation. R2 in each panel for the regressions on all banks, with in situ, and without in situ, speciation are respectively: a, 0.85, 0.90, 0.11; b, 0.57, 0.89, 0.31; c, 0.32, 0.65, 0.22; d, 0.15, 0.65, 0.01. See Table 1 for the multivariate regressions.

Does area now explain more, and isolation less, of the variation in anole richness? By adding species to impoverished islands, increased colonization should move islands towards their area-set saturation points, strengthening the SAR; and because isolated islands, especially those too small for in situ speciation, should be impoverished, the SIR should weaken. In the past, a strong, negative SIR existed (Table 1, Fig. 2c) with the most isolated banks also the most impoverished in native anoles (P ≪ 0.001, Extended Data Table 3). As predicted, the SIR has now weakened while the SAR has strengthened (Fig. 2b, d, Table 1, Extended Data Table 5). This shift is because isolation now correlates positively with the richness of newly colonized species, a reversal of the natural pattern, but like the natural pattern, exotic richness positively correlates with area, further strengthening the present-day anole SAR (see the exotic model in Table 1).

Our results support the theory that it is the influence of geographic area and isolation on long-term biogeographic processes such as speciation and colonization that fundamentally determine island biodiversity1,2,4,10. However, as the species richness of isolated islands is increasing, Caribbean anoles are not currently in equilibrium and island isolation no longer inhibits colonization by new species (Figs 1, 2d; Table 1). Yet, this latter conclusion rests on defining isolation relevant to the natural over-water colonizing ability of lizards. In the modern world, anoles colonize as commensals of humans arriving at new destinations primarily as stowaways in cargo shipments (Extended Data Table 1). In this context, island isolation should be redefined to be relevant to this new way in which islands gain species.

Translocating species to new destinations is one of the many ways humans alter Earth. Human effects are so pervasive that a new epoch for the present day, the Anthropocene, has been proposed23. Proponents argue that an anthropogenic perspective is necessary to understand current and future trajectories of Earth systems24,25. Beginning with the Industrial Revolution, multiple indicators of human activity (for example, atmospheric CO2 concentration) slowly increased, but then following the Second World War (WWII) increased rapidly23. The establishment of exotic anoles follows such a curve (Fig. 3). Establishment rate increased first after WWII, and again following the end of the Cold War when global shipping more than doubled26. An Anthropocene perspective may thus well apply to understanding present-day island isolation, and we interpret our final results in this context.

The accumulation of exotic anole lizard species across the Caribbean is best explained by a three-segment regression (P ≪ 0.001) with breakpoints (*) estimated at 1961 (1943–79 CI95%, horizontal bars) and 1999 (1997–2002), and rates of 0.07 (±0.01 s.e.m.), 0.23 (0.07), 0.96 (0.12) exotic establishments per year.

Shipping traffic among Caribbean banks is not related to geographic isolation (Extended Data Table 6)27. Instead, variation in shipping is dependent on anthropogenic factors that influence trade (for example, the US–Cuban trade embargo)28. We estimated the economic isolation of Caribbean banks from a global maritime shipping-traffic data set27 and asked if this metric explained anole richness.

Economic isolation determines Caribbean biodiversity in the Anthropocene—both exotic and present-day (that is, native + exotic) anole richness were negative functions of economic isolation (Table 2, Extended Data Table 5). Further, the correlation between area and economic isolation was high (ρ = −0.74, P ≪ 0.001), implicating shipping trade as the mechanism underlying the positive exotic SAR (Table 1). Therefore, two mechanisms, natural and anthropogenic, underlie the shifting importance of area and isolation in determining past from present anole biogeography (Tables 1 and 2, Extended Data Table 2). As expected if area determines saturation points, isolated banks without in situ speciation are impoverished in native species (Extended Data Table 3) and are consequently gaining exotics to strengthen the anole SAR, yet because the trade that disperses anoles is constrained by area (for example, larger banks have more people and ports), the SAR is also strengthening because there is a negative economic isolation–area relationship (EIAR, Extended Data Fig. 4a).

Anthropocene models of island biogeography must include economic isolation. For example, the US embargo strongly increases Cuban economic isolation (Extended Data Fig. 4b). We estimated Cuban economic isolation without an embargo from the Caribbean EIAR, and then estimated the expected number of exotic anoles from the exotic model in Table 2 (Extended Data Fig. 4c). Given the current rate of exotic establishment (Fig. 3), we predict Cuba would rapidly gain 1.65 anole lizard species (95% confidence interval, CI95%, 1.06–2.57) should trade normalize following embargo cessation; this gain is comparable to that already seen on Hispaniola, a bank of similar area but without a trade embargo. As the native biodiversity of islands such as Cuba is extraordinary and economically important, strategies (such as cargo screening, ecological monitoring and species import bans) to prevent the establishment and impact of exotic species must increase as economic isolation decreases. Just as for models of other Earth systems, biogeographic models must now include anthropogenic forcing to understand, predict and mitigate the consequences of the new island biogeography of the Anthropocene.

Methods

We constructed a data set of native and exotic (34 establishments) anole distributions across 39 Caribbean banks with an exhaustive literature search and by contacting anole experts. All Caribbean-region banks with documented introductions were analysed along with all banks that have endemic species (Extended Data Fig. 1). All banks were within nations of the Caribbean Community and Common Market (CARICOM) group, a geopolitical economic development organization that influences Caribbean trade. To test for phylogenetic underdispersion, we calculated the mean relatedness of species in past and present bank assemblages and compared the mean across banks to null distributions derived by randomizing species across banks21. Bank area was estimated as total dry land area. Isolation was based on our current understanding of anole ancestral biogeography (Extended Data Fig. 1)13,19,29, estimated as the square root9 of: total pairwise distance from all banks, distance from Cuba, distance from northern South America, and total distance from both Cuba and northern South America (that is, the estimated origins of all Caribbean anoles). We then performed a principal component analysis and used the resultant axes as isolation metrics (Extended Data Table 4). Economic isolation was the total number of ships docking on each bank from anywhere within the Caribbean region in 2007–0827, divided by the maximum value across banks and subtracted from one (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Alternative economic isolation metrics (for example, total cargo tonnage per ship) were highly correlated and produced the same conclusions. Regressions in Tables 1 and 2 were Gaussian and data met model assumptions. We tested the sensitivity of our results by: using an alternative ancestral origin (Hispaniola), removing banks without natives, removing the Greater Antilles, removing Bermuda, using alternative species definitions, including bank age, and finally using an alternative data set30 of 43 Caribbean banks with 21 exotic establishments (Extended Data Table 5).

References

MacArthur, R. H. & Wilson, E. O. The Theory of Island Biogeography (Princeton Univ. Press, 1967)

Losos, J. B. & Ricklefs, R. E. The Theory of Island Biogeography Revisited (Princeton Univ. Press, 2010)

Lomolino, M. V. A call for a new paradigm of island biogeography. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 9, 1–6 (2000)

Heaney, L. R. Dynamic disequilibrium: a long-term, large-scale perspective on the equilibrium model of island biogeography. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 9, 59–74 (2000)

Schoener, T. W. in The Theory of Island Biogeography Revisited (eds Losos, J. B. & Ricklefs, R. E. ) 53–85 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2011)

Losos, J. B. & Schluter, D. Analysis of an evolutionary species–area relationship. Nature 408, 847–850 (2000)

Kisel, Y. & Barraclough, T. G. Speciation has a spatial scale that depends on levels of gene flow. Am. Nat. 175, 316–334 (2010)

Wagner, C. E., Harmon, L. J. & Seehausen, O. Cichlid species-area relationships are shaped by adaptive radiations that scale with area. Ecol. Lett. 17, 583–592 (2014)

Gillespie, R. G., Claridge, E. M. & Roderick, G. K. Biodiversity dynamics in isolated island communities: interaction between natural and human-mediated processes. Mol. Ecol. Notes 17, 45–57 (2008)

Rosindell, J. & Phillimore, A. B. A unified model of island biogeography sheds light on the zone of radiation. Ecol. Lett. 14, 552–560 (2011)

Wilson, E. O. & Simberloff, D. S. Experimental zoogeography of islands: defaunation and monitoring techniques. Ecology 50, 267–278 (1969)

Whittaker, R. J., Field, R. & Partomihardjo, T. How to go extinct: lessons from the lost plants of Krakatau. J. Biogeogr. 27, 1049–1064 (2000)

Rabosky, D. L. & Glor, R. E. Equilibrium speciation dynamics in a model adaptive radiation of island lizards. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 22178–22183 (2010)

Schoener, T. W. & Schoener, A. The time to extinction of a colonizing propagule of lizards increases with island area. Nature 302, 332–334 (1983)

Blackburn, T. M., Cassey, P. & Lockwood, J. L. The island biogeography of exotic bird species. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 17, 246–251 (2008)

Sax, D. F. et al. Ecological and evolutionary insights from species invasions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22, 465–471 (2007)

Kerr, J. T., Kharouba, H. M. & Currie, D. J. The macroecological contribution to global change solutions. Science 316, 1581–1584 (2007)

Sax, D. F. & Gaines, M. S. Species invasions exceed extinctions on islands worldwide: a comparative study of plants and birds. Am. Nat. 160, 766–783 (2002)

Losos, J. B. Lizards in an Evolutionary Tree (Univ. California Press, 2009)

Ojeda Kessler, A. G. Status of the Culebra Island giant anole (Anolis roosevelti). Herpetol. Conserv. Biol. 5, 223–232 (2010)

Helmus, M. R. & Ives, A. R. Phylogenetic diversity-area curves. Ecology 93, S31–S43 (2012)

Poe, S. Comparison of natural and nonnative two-species communities of Anolis lizards. Am. Nat. 184, 132–140 (2014)

Steffen, W., Grinevald, J., Crutzen, P. J. & McNeill, J. The Anthropocene: conceptual and historical perspectives. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 369, 842–867 (2011)

Thomas, C. D. The Anthropocene could raise biological diversity. Nature 502, 7 (2013)

Mendenhall, C. D., Karp, D. S., Meyer, C. F. J., Hadly, E. A. & Daily, G. C. Predicting biodiversity change and averting collapse in agricultural landscapes. Nature 509, 213–217 (2014)

Essl, F., Winter, M. & Pysek, P. Biodiversity: trade threat could be even more dire. Nature 487, 39 (2012)

Morinière, V. & Réglain, A. Development of a GIS-based Database for Maritime Traffic in the Wider Caribbean Region (Strategic Plan 10-11, Activity 4.6.b.2., UNEP RAC/REMPEITC-Caribe, 2012)

Bhagwati, J. Protectionism (MIT Press, 1988)

Mahler, D. L., Revell, L. J., Glor, R. E. & Losos, J. B. Ecological opportunity and the rate of morphological evolution in the diversification of greater antillean anoles. Evolution 64, 2731–2745 (2010)

Powell, R. & Henderson, R. W. Island lists of West Indian amphibians and reptiles. Florida Mus. Nat. Hist. Bull. 51, 85–166 (2012)

Pagel, M. Detecting correlated evolution on phylogenies: a general method for the comparative analysis of discrete characters. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 255, 37–45 (1994)

Helmus, M. R., Bland, T. J., Williams, C. K. & Ives, A. R. Phylogenetic measures of biodiversity. Am. Nat. 169, E68–E83 (2007)

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Behm, J. Ellers, A. Ives, C. Pfister, J. Vermaat and T. Wootton for critical feedback; S. Buckner, S. Charles, A. Fields, M. López Darias, G. Perry, R. Platenberg, R. Powell, G. Reynolds, A. Sanchez, G. van Buurt and G. Wever for information on anole introductions; and A. Reglain for access to the RAC/REMPEITC-Caribe UNEP shipping traffic data set. M.R.H. was supported by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (858.14.040) and the US National Science Foundation (DBI 0906011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.R.H. conceived of the study, built the data sets and wrote the manuscript. M.R.H and D.L.M. performed the analyses. J.B.L. was involved in study design and contributed data. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Figure 1 Bayesian maximum clade credibility phylogeny of Caribbean Anolis lizards with estimates of geographic history based on native species distributions.

The relative likelihoods of character states at internal nodes31 are depicted as pie charts and are coloured by geography (see tip colours and labels). Grey boxes encompass nodes and edges with relative log likelihood for a mainland state >0.005. Six banks here are identified as having had cladogenetic (in situ) speciation: the Greater Antilles (as previously reported6), St Vincent and Guadeloupe—St Vincent because our phylogeny13,21,29 is different from the phylogeny of the previous work6, and Guadeloupe because unlike the previous work6 we aggregated islands to banks.

Extended Data Figure 2 Caribbean anole bank saturation and the effect of isolation on the species–area relationship (SAR).

a, We used the residuals from a linear regression (dashed line) of the bank SAR and deviations from a 90% quantile regression (dotted line in a–c) of the SAR of islands within the Cuban bank as estimates of native anole saturation (Extended Data Table 2 and 3). SR is species richness. The two metrics of saturation were strongly correlated (ρ = 0.989, P ≪ 0.001). b, Cuban islands span the range of areas exhibited by Caribbean banks and are much less isolated and nearby to Cuba, the most species-rich island in the Caribbean. Our 90% quantile regression is analogous to calculations of island saturation curves based on drawing a line between a source island and a species-rich island very near to the source1. c, In the present day, bank richness has not exceeded the saturation curve, an indication that banks are not currently oversaturated with anoles. Filled symbols indicate banks with exotics. d, Isolation determines much of the nonlinear relationship between past (that is, native) anole richness and area (Fig. 2a) and validates our use of a linear model for the analyses in Tables 1 and 2. The ordinate is the residual from a regression of past species richness on the three isolation metrics, and unlike the raw SAR in a, a linear model (solid line), and not a breakpoint model (Fig. 2a), best fit the data.

Extended Data Figure 3 The loss of the Caribbean anole negative phylogenetic diversity–isolation relationship (PDIR).

a, In the past there was a strong negative PDIR (P = 0.003), but in the present day (b), this negative relationship has been reduced by 71% and c, is no longer significant (see Table 1 footnote for definitions of the values in c). Phylogenetic species variability (PSV) is the mean relative phylogenetic relatedness of all species on a bank32. Red points are banks with, and blue points banks without, in situ speciation. Filled symbols show banks with exotics. Grey points in b are banks that in the past had <2 anole species, but with exotic colonization now have 2 or more species such that PSV can now be calculated32. Note that to be comparable, both the PSV regressions in c are only on the banks with 2 or more native species. Variation in PSV is caused both by colonization and in situ speciation. Specifically, (1) Jamaica, Guadeloupe and St Vincent have low PSV because they are derived from one colonization and then in situ speciation (Extended Data Fig. 1); (2) Grenada, St Eustatius, Anguilla and Antigua have low PSV because each of their two colonizations came from the same clade; (3) Cay Sal, Little Cayman and Acklins have high PSV because they had colonizations from distantly related clades originating from Cuba—each had a natural colonization of the ubiquitous Anolis sagrei and of an ancestor from the carolinensis clade; (4) Great Bahama has high PSV because it received colonizations from both Hispaniola and Cuba; and (5) Cuba, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico have high PSV because they have had much in situ speciation derived from multiple colonizations.

Extended Data Figure 4 The effect of the US trade embargo on Cuban economic isolation.

a, There is a negative economic isolation–area relationship (EIAR) across Caribbean banks. b, The largest residual (studentized) of the EIAR (line in a) is Cuba. c, The predicted economic isolation of Cuba (× symbol) if the trade embargo is lifted, based on the EIAR.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Data

This file contains source data for Table 1. (XLSX 14 kb)

Supplementary Data

This file contains source data for Table 2. (XLSX 15 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Helmus, M., Mahler, D. & Losos, J. Island biogeography of the Anthropocene. Nature 513, 543–546 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13739

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13739

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Local human impacts disrupt depth-dependent zonation of tropical reef fish communities

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2023)

-

Depth zonation of reef fish is predictable but disrupted on contemporary coral reefs

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2023)

-

Island characteristics and species traits predict mammal diversity across islands of the great lakes of North America

Biodiversity and Conservation (2023)

-

Original karst tiankeng with underground virgin forest as an inaccessible refugia originated from a degraded surface flora in Yunnan, China

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Naturalized alien floras still carry the legacy of European colonialism

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2022)