Abstract

Woodsmoke contains harmful components — such as fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) — and impacts more than half of the global population. We investigated urinary hydroxylated PAH metabolites (OH-PAHs) as woodsmoke exposure biomarkers in nine non-smoking volunteers experimentally exposed to a wood fire. Individual urine samples were collected from 24-h before to 48-h after the exposure and personal PM2.5 samples were collected during the 2-h woodsmoke exposure. Concentrations of nine OH-PAHs increased by 1.8–7.2 times within 2.3–19.3 h, and returned to baseline approximately 24 h after the exposure. 2-Naphthol (2-NAP) had the largest post-exposure increase and exhibited a clear excretion pattern in all participants. The level of urinary OH-PAHs, except 1-hydroxypyrene (1-PYR), correlated with those of PM2.5, levoglucosan and PAHs in personal PM2.5 samples. This finding suggests that several urinary OH-PAHs, especially 2-NAP, are potential exposure biomarkers to woodsmoke; by contrast, 1-PYR may not be a suitable biomarker. Compared with levoglucosan and methoxyphenols — two other urinary woodsmoke biomarkers that were measured in the same study and reported previously — OH-PAHs might be better biomarkers based on sensitivity, robustness and stability, particularly under suboptimal sampling and storage conditions, like in epidemiological studies carried out in less developed areas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.INTRODUCTION

More than half of the global population is exposed to household smoke from the indoor burning of wood, coal, charcoal, and crop residues for cooking and/or heating.1 People are also exposed to woodsmoke through wildfire, agricultural burning, and recreational burning, particularly in certain workers, such as firefighters. Components of woodsmoke include particulate matter (PM) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), which are associated with a variety of adverse health outcomes, including cancer.2, 3, 4, 5 Exposure to woodsmoke has been linked to respiratory symptoms, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and low birth weight and stillbirth.6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Indoor smoke from solid fuels was ranked as the fourth leading risk factor for disease burden — behind underweight, unsafe sex, and poor water sanitation and hygiene — in the world’s poorest regions.11

Stove improvement and replacement programs12, 13 are implemented worldwide to reduce human exposure to woodsmoke as well as the potential disease and socioeconomic burdens associated with such exposure. To evaluate and guide such programs and investigate woodsmoke exposure, it is essential to have an accurate, effective, and robust characterization of personal exposure to woodsmoke.14 One common approach involves measuring smoke components, such as fine particles less than 2.5 μm in diameter (PM2.5), carbon monoxide, PAHs, and levoglucosan, in personal air samples.12, 13, 15 However, personal air sampling could be inconvenient and burdensome for participants. In addition, measurement of pollutants in air samples does not account for individual physiological differences and personal behaviors that can affect the uptake, absorption, distribution, and metabolism of the air pollutants.

Alternatively, exposure in humans can be studied by measuring exposure biomarkers.16 This approach reduces uncertainties related to spatial and temporal variations in pollutant levels in the environment, and uncertainties related to the individual differences in pollutant uptake. Furthermore, unexpected episodic exposures might not be feasibly captured by environmental monitoring. Biological samples collected after the exposure could readily reflect that exposure, especially with an understanding of biological half-lives and the pharmacokinetics of the biomarkers.

Several chemicals or classes of chemicals have been proposed as woodsmoke exposure biomarkers,17 such as urinary levoglucosan18, 19, 20 and methoxyphenols.21 Urinary hydroxylated PAHs (OH-PAHs), a group of PAH metabolites,22, 23, 24, 25 have been used as biomarkers of exposure to PAHs, with 1-hydroxypyrene (1-PYR) as the most commonly used indicator.26, 27 A number of studies have used urinary OH-PAHs as the woodsmoke exposure biomarker to investigate stove emissions and evaluate the effectiveness of stove intervention efforts.28, 29, 30, 31

We report here nine OH-PAHs, metabolites of naphthalene, fluorene, phenanthrene, and pyrene, in urine specimens collected from nine participants experimentally exposed to woodsmoke for 2 h. We studied the excretion profiles of the urinary PAH metabolites from 24-h before to 48-h after the woodsmoke exposure. We also investigated the relationship between the PAH metabolites and the air pollutants on personal air samples collected during the 2-h exposure. This is the first study, to the best of our knowledge, that measured all three major biomarker classes for woodsmoke — levoglucosan,19 methoxyphenols,32 and PAH metabolites — in the same urine specimens. We compared these proposed biomarkers with regard to sensitivity, specificity, and practicality for assessing woodsmoke exposure in epidemiological studies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

The nine volunteers (four males and five females) were healthy adults between 20 and 65 years of age, self-reported non-smokers, and not occupationally exposed to PAHs at the time of this study (August, 2003). From 2 days prior to 2 days after the controlled woodsmoke exposure, the participants avoided food cooked on open fires or food and drinks containing woodsmoke flavorings, and avoided exposure to second-hand smoke.32

During the 2-h controlled exposure period, volunteers stayed in a closed hexagonal yurt-like structure with a camp fire burning a mixture of barkless softwood and hardwood at the center. The hexagonal yurt (3 m sides, 2.4 m height, approximately 23 m2 area and 55 m3 volume) contained an adjustable smoke vent (0.9–1.8 m2) centered in the ceiling above the fire. Temperature in the yurt rose through the exposure period from 21 °C to 36 °C (mean 32 °C). Participants sat approximately 0.75 m from the fire within 2 m from each other. They were allowed to move within the yurt and moderate their exposure at will. Each person collected a personal PM2.5 sample at the breathing zone during the exposure period using a Harvard Personal Environmental Monitor for PM2.5 at a flow rate of 4 l/min (Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA).

Urine Sampling

For 24 h before the exposure, participants collected urine voids at will in separate containers for baseline measurements. The participants did not void during the 2-h exposure period, and then collected all urine voids at will for 48 h after the exposure. The participants collected each urine void in a pre-labeled polyethylene container, recorded the date and time of each void, and placed the container in an ice cooler or refrigerator. Participants delivered their urine samples to the laboratory each day, whereupon volume was measured for each sample. The samples were separated into aliquots, and stored at −20 °C. Samples were shipped frozen on dry ice to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and stored at −70 °C until analysis for OH-PAHs in March, 2009. The study protocol was approved by the Human Research Protection Office at the CDC and the Human Subjects Division at University of Washington. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrolling in the study.

Sample Analyses

We analyzed 13 urine voids per subject (3 pre-exposure samples and 10 post-exposure samples). Voids to be analyzed were selected to ensure consistent temporal coverage over the 48-h post exposure period, with deliberate over-sampling of voids collected in the first 24-h post exposure when urinary metabolite levels were expected to be changing most rapidly. A total of 117 urine samples were analyzed for OH-PAHs based on a method33 certified by the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services according to the guidelines set forth in the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments Act (CLIA). Briefly, urine samples (2 ml) were spiked with a mixture of 13C-labeled internal standards and sodium acetate buffer containing β-glucuronidase and sulfatase, hydrolyzed overnight at 37 °C, and then extracted by a solvent mixture (80% pentane and 20% toluene, v-v) through semi-automated liquid-liquid extraction. The extracts were evaporated, derivatized, and analyzed by isotope dilution gas chromatography high resolution mass spectrometry to quantify nine OH-PAHs: 1-, 2-naphthol (1-NAP and 2-NAP), 2-, 3-, 9-hydroxyfluorene (2-FLU, 3-FLU, and 9-FLU), 1-, 2-, 3-hydroxyphenanthrene (1-PHE, 2-PHE, and 3-PHE) and 1-PYR. Each analyte had its own 13C-labeled internal standard. All analyses were subjected to a series of quality control and quality assurance checks as described elsewhere.33 The limits of detection ranged 0.003–0.018 μg/l, and the detection frequency ranged 95–100% for the nine OH-PAHs. Urinary creatinine was measured on a Roche Hitachi 912 Chemistry Analyzer (Hitachi, Pleasanton, CA, USA) by use of the Creatinine Plus Assay, as described in Roche’s Creatinine Plus Product Application # 03631761003.

Personal PM2.5 samples were extracted and analyzed by gas chromatography mass spectrometry for 20 PAHs and levoglucosan and reported previously.32

Data and Statistical Analyses

Urinary OH-PAH concentrations below limits of detection were replaced with the limits of detection divided by square root of 2. Creatinine correction was applied to urinary results to account for urine dilution known to vary with the hydration status of the subject, and creatinine-adjusted concentration was used for all analyses. All statistical analyses were performed through SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) or R software (R Development Core Team, 2010).

We defined the starting time of the woodsmoke inhalation exposure as t =0 h, the pre-exposure period as −24 < t ≤0 h, and the post-exposure baseline period as 24< t ≤50 h. The observed pre-exposure level in each person was calculated as the average concentrations in the three urine specimens taken during −24−0 h, and the post-exposure level was characterized as the average concentration in urine collected during three separate time segments, that is, 0–12 h (3.7±1.0 samples/person), 12–24 h (2.1±0.6 samples/person), and 24–50 h (4.2±0.8 samples/person), to illustrate the uptake, excretion, and baseline phases, respectively.

We studied the association between the urine metabolite levels and the air pollutant levels on the personal air samples (PM2.5, levoglucosan, and PAHs). The urine biomarker levels in each participant were defined in two ways: (i) the average concentration in urine taken during 0–12 h, and (ii) the maximum post-exposure concentration. Because of the small sample size (seven data pairs for 1-NAP and nine data pairs for the remaining OH-PAHs), we conducted linear regression and nonparametric Spearman’s rank correlation analyses. Both methods gave comparable results, therefore, we only present results from the linear regression analysis. Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) was considered statistically significant when P-value was equal to or less than 0.05, and marginally significant when P was between 0.05 and 0.10.

The data for each OH-PAH were combined from all participants and analyzed using a non-linear mixed effects model34 to calculate the mean background level, mean uptake level, mean decay rate parameter, and the population median half-life (t1/2). The model took into account background exposure, first order decline of metabolites following exposure, and between-subject variation in pharmacokinetics.35 We included the data prior to the controlled woodsmoke exposure (pre-exposure, t ≤0 h) and after the observed time of peak urinary concentration (post-peak, t ≥ tmax), and omitted the data during the uptake phase.

RESULTS

Concentrations of PM2.5, levoglucosan, and PAHs on the personal PM2.5 samples that the nine volunteers collected during their 2-h woodsmoke exposure are given in Supplementary Table S1. Personal PM2.5 concentrations ranged from 840 μg/m3 (Participant C) to 3000 μg/m3 (Participant B), averaging 1515±682 μg/m3 among the participants.32 The PM2.5-bound PAH concentrations were 36.9±4.8, 10.7±3.1, 7.2±1.2, 19.7±13.6, and 46.6±20.8 ng/m3 for naphthalene (NAP), fluorene (FLU), phenanthrene (PHE), pyrene (PYR), and benzo[a]pyrene, respectively.

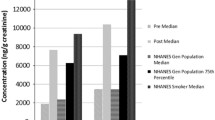

As shown in Table 1, the observed pre-exposure OH-PAH concentrations in the participants were at similar level or lower than those in the U.S. adult population (20 years of age and older).36 Urinary OH-PAH levels increased by up to 28 times in the participants within hours after the inhalation exposure, then gradually decreased to baseline levels approximately 24 h after the exposure. Figure 1 gives the box-and-whisker plots of the average urinary concentrations for 2-NAP and 1-PYR in all participants during pre-exposure (−24−0 h) and three time segments post-exposure (0–12 h, 12–24 h, and 24–50 h). The time course of creatinine-adjusted concentrations of the nine OH-PAHs from participant G is given in Figure 2 and other participants are represented in Supplementary Figures S1~S8. Most urinary PAH metabolites in Participant C did not show the anticipated pattern corresponding to the exposure (Supplementary Figure S3), which might be explained by the lowest personal PM2.5 level in this person compared with the rest of the participants.32 Therefore, data from Participant C were excluded from the pharmacokinetic model analysis.

Among the nine OH-PAHs, 2-NAP had the largest increase after the inhalation exposure — averaging 7.2 times (1.9–28 times) among the participants — followed by 1-NAP (4.5±2.1 times) and 9-FLU (4.4±4.0 times), as shown in Supplementary Table S2. Urinary 2-NAP levels in all participants displayed the anticipated excretion profile (Figure 3), that is, an initial rapid increase after the exposure, followed by a decrease to baseline concentration consistent with background exposure after approximately 24 h. The rest of OH-PAHs generally followed a similar pattern, although with some exceptions. Most notably, 1-NAP, an isomer of 2-NAP — both metabolites of naphthalene — peaked before the exposure in Participants C and E, and decreased throughout the monitoring period (Supplementary Figures S3 and S5), indicating a substantial source of 1-NAP other than naphthalene in the woodsmoke for these two persons. For example, 1-NAP is also a main metabolite of the wide-spectrum carbamate insecticide carbaryl,37 the herbicide napropamide,38 and the widely used beta-blocker propanolol.39 Therefore, 1-NAP data from these two persons were excluded from further data analysis.

With the exception of 1-PYR, the urinary PAH metabolite concentrations correlated with PM2.5, levoglucosan, benzo[a]pyrene, and the corresponding parent PAHs in the personal air samples (Table 2). Example linear regression plots of urinary 2-NAP and 3-PHE against PM2.5 are given in Supplementary Figure S9. Both the average concentration during 0–12 h post exposure and the maximal post-exposure concentration were used in the linear regression analysis and both gave similar results (Table 2). 1-PYR was the only urinary PAH metabolite that did not correlate with air pollutants, including pyrene, its parent compound.

Table 3 gives the pharmacokinetic parameters for the excretion of the PAH metabolites, estimated using a non-linear mixed effects model with a term for background exposure. The modeled mean background and uptake levels for the OH-PAHs were highly consistent with the corresponding observed mean levels presented in Supplementary Table S2. The two smallest PAH metabolites had the shortest t1/2 of approximately 6 h. The largest PAH metabolite measured in the study, 1-PYR, had the longest t1/2 (24 h), albeit the 95% confidence intervals on this estimate were broad (13.5–92.0 h). The t1/2 for the remaining OH-PAHs, metabolites of fluorene and phenanthrene, ranged 8–15 h.

DISCUSSION

In general, OH-PAH concentrations increased after the woodsmoke exposure, reaching a maximum within 2.4–19.3 h (Table 1) and returning to the pre-exposure baseline approximately 24 h after the exposure. Notably, 2-NAP had the largest increase after the exposure and exhibited a clear rise-fall excretion pattern in all participants (Figure 3). This is consistent with the previous suggestion that 2-NAP is a more suitable biomarker for inhalational exposure to PAHs30, 40, 41 than the other OH-PAHs.

Despite the small sample size (n=7 for 1-NAP, n=9 for the remaining OH-PAHs), eight urinary OH-PAHs (except 1-PYR) were significantly associated with PM2.5 and levoglucosan in the personal air samples with r as high as 0.93 (Table 2). Generally, these OH-PAHs were also correlated with PAHs in the PM2.5 samples, although to a less extent. This is not surprising, considering PAHs are distributed into both gaseous and particle phases in air. Small PAHs with two to three aromatic rings, such as naphthalene, fluorene, and phenanthrene, exist primarily in the gaseous phase, whereas those with four or more rings (e.g., pyrene and benzo[a]pyrene) are primarily in the particle phase.42, 43, 44 Therefore, small PAHs on the PM2.5 filters only represent a minor portion of total PAHs in air, which would affect the correlation with the urinary PAH biomarkers.

Post-exposure 1-PYR levels — evaluated using maximum, average 0–12 h, and average 0–24 h concentrations (data not shown) — were not significantly correlated with any of the air pollutants in personal PM2.5 samples, including pyrene. It has been suggested that diet is likely a primary source for urinary 1-PYR in populations that are not knowingly exposed to high levels of PAHs.45 An earlier study on charcoal workers reported that 1-PYR was less sensitive than 2-NAP for monitoring woodsmoke exposure.46 Other potential factors include the relatively low exposure and small sample size (n=9) in this study, and the longer t1/2 compared with the other OH-PAHs. Although 1-PYR is the most common and often the only biomarker used in PAH exposure studies, our results suggested that 1-PYR is not the appropriate biomarker for relatively low inhalational exposures.

The t1/2 for the metabolites of naphthalene, fluorene, and phenanthrene ranged 6.3–14.7 h (Table 3), which is consistent with previous reports on inhalation exposures. The t1/2 for 1-NAP was 4 h in workers conducting naphthalene oil distillation.47 The t1/2 in eight smokers after cigarette smoking averaged 9.4 h (range 4.9–12.2 h) for 2-NAP and ranged 4.1–8.2 h for the fluorene metabolites.48 Among 20 asphalt pavers who were exposed through both inhalation and dermal absorption, t1/2 was 26 h (95% CI: 14–116 h) for naphthols (summation of 1-NAP and 2-NAP) and 14 h (95% CI: 9.0–28 h) for phenanthrols (summation of 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 9-PHE).49

The modeled t1/2 for 1-PYR (23.5 h, 95% CI: 13–92 h), the largest among the 9 OH-PAHs measured, was similar to the mean t1/2 (29 h, range 6.4–128 h) among 17 locomotive engine workers exposed to diesel exhaust.50 1-PYR’s estimated t1/2 in this study was longer than most reported half-lives after inhalation exposure. For example, in five subjects who breathed workplace air at an aluminum plant for 6 h, the 1-PYR excretion t1/2 was 9.8 h (95% CI: 7.9–12 h).51 The mean t1/2 was 6.1 h (range 1.9–12.5 h) among seven workers at an artificial shooting target factory using petroleum pitch as the basic binder.52 After cigarette smoking, the t1/2 averaged 6.0 h (range 3.7–9.9 h) in eight smokers.48

It should be noted that most studies on elimination kinetics of OH-PAHs have focused on heavily exposed populations, such as occupationally exposed workers52 and smokers.48 Conducting pharmacokinetic modeling on populations with modest exposure, such as this study group, is more challenging. For example, the 1-PYR concentration immediately post exposure (0–12 h) merely reached the median level in the U.S. adults, and the maximum concentration were equivalent to the 75th percentile of the U.S. adult population (Table 1). The maximum 1-PYR levels in this study were up to two orders of magnitude lower than the populations from which elimination half-lives were available. Therefore, the relatively low exposure from the 2-h woodsmoke inhalation, in combination with the relatively high and variable background from other sources, for example, diet, could lead to an overestimate of the excretion half-life for 1-PYR in this study.

As illustrated in Figures 2 and 3, the urinary biomarker concentration varied largely within a few hours after an exposure. Therefore, when using biomonitoring for exposure assessment, it is essential to have an appropriate biological sampling scheme to capture and quantify potential exposure. This is especially important for episodic exposure to short-lived non-persistent chemicals that are metabolized and excreted rapidly in urine, such as PAHs.

With the exception of 1-PYR, the maximal concentrations of OH-PAHs post-exposure were highly correlated with personal exposure to PM2.5 in woodsmoke (r =0.69–0.93, Table 2). However, it is impossible to time the sampling to collect a single urine specimen at the peak excretion in a person. To simulate the use of a spot sample, we randomly selected one sample from each person during 0–12 h and conducted a similar correlation analysis. As expected, we found poor correlations between the urinary OH-PAHs in simulated spot samples with air pollutants (data not shown). On the other hand, the average concentrations in the urine specimens collected during 0–12 h were highly associated with PM2.5 in personal air samples, with r ranging 0.70–0.90, except 1-PYR (Table 2). This demonstrates that, if possible, collection of multiple urine samples during the period post exposure will produce a better estimate than collecting a single spot urine sample after an episodic exposure. The cost of analysis can further be reduced by pooling multiple samples collected to obtain an estimate of the average exposure.

On the other hand, most exposure scenarios are not a one-time event, but occur continuously or comprise a series of recurrent events, for example, exposure to household air pollution from cookstove emissions. Such exposure would exhibit an excretion profile different from the one obtained in this single exposure study, and could allow the concentration from a spot urine sample of an individual to be better comparable with other populations.53 Nevertheless, study protocols should still include consistent urine sampling timing and method.53

This is the first study that we know of measuring all three proposed urinary woodsmoke biomarkers,17 that is, urinary levoglucosan,19 methoxyphenols,32 and OH-PAHs. This provided a unique opportunity to evaluate these biomarkers based on the following aspects. First and foremost, an exposure biomarker needs to be a sensitive and dose-dependent indicator of exposure. Second, it should have adequate specificity for providing inference to an exposure source or pathway. Third, it should be biologically stable and robust in a matrix that is obtained by the least invasive means possible. These factors, along with the potential costs of collecting, maintaining, transporting, and analyzing specimens, should be considered for large epidemiological studies, particularly in less developed areas with limited resources where most stove improvement programs take place.14

Levoglucosan, a sugar anhydride produced during the pyrolysis of cellulose, has been used as a specific tracer for biomass burning in PM source apportionment.54, 55 Several studies have used urinary levoglucosan as a biomarker to assess human exposure to woodsmoke.18, 19, 20 Among the nine participants in this study, however, only one showed an increasing urinary levoglucosan level, whereas the remaining participants did not respond consistently to the exposure.19 This could be due to relatively low exposure levels and short duration in this study, or, as suggested, potential confounding sources for levoglucosan that were not excluded during study design, such as caramel-containing food known to contain levoglucosan.19

Methoxyphenols are formed during the pyrolysis of the wood polymer lignin and have been suggested as markers for biomass burning in air samples56 and biomarkers in urine.21 Among the 21 methoxyphenols measured, several compounds reached peak of elimination at approximately 5–6 h post exposure, whereas many other compounds, such as eugenol and vanillin, did not show a clear peak of elimination.32 Ten urinary methoxyphenols had significantly positive association with levoglucosan and PM2.5 in air (r: 0.70–0.91), whereas nine had no or negative association with the air pollutants (r: −0.34–0.16).32 Dills et al.32 further suggested using the summed concentrations of five methoxyphenols with the largest post exposure increase as a woodsmoke indicator, because of their high response to exposure and high correlation with levoglucosan and PM2.5 in the personal air samples.

Concentrations of most urinary OH-PAHs, except 1-PYR, were correlated with those of levoglucosan and PM2.5 in the personal air samples. The Pearson’s correlation coefficients ranged 0.68–0.90 (using the average 0–12 h post exposure concentration, Table 2), which were similar or higher than those of urinary methoxyphenols against PM2.5 and levoglucosan. This suggests that the sensitivity of urinary PAH metabolites as woodsmoke biomarkers is similar, if not better, than that of the urinary methoxyphenols. Further, both biomarker classes appear to be more sensitive to woodsmoke exposure than urinary levoglucosan that did not exhibit post-exposure increase in most participants.

Specificity to an exposure source is a common challenge for biomonitoring, because biomarkers reflect collective exposure from all sources and routes over a period of time. PAHs are products of incomplete combustion and are also present in unburned petroleum products. Therefore, diet, air pollution, and cigarette smoke are potential sources for PAH exposure for the general population who are not occupationally exposed to high levels of PAHs. Incidental sources such as drug or pesticide exposures are likely to affect 1-NAP concentrations. Diet can also be a potential source for methoxyphenols (food containing woodsmoke flavoring) and levoglucosan (caramelized sugar).17 Hence, all three urinary woodsmoke biomarker classes are limited with regard to specificity, and OH-PAHs have the most potential sources. Nonetheless, in a well-designed study, the alternative sources can be avoided or minimized by employing appropriate dietary and activity restrictions, which would enable linking the biomarkers with the target source.

Robustness and stability of the biomarkers are additional considerations that are often not considered. This is especially important for conducting epidemiological studies in less developed areas, for example, large-scale stove intervention programs, where specimen storage and handling may not be ideal. OH-PAHs, excreted in urine as glucuronide and sulfate conjugates, are stable at 37°C for 2 days or longer (tested at dark in an oven set at 37 °C, Supplementary Figure S10). This can be beneficial in studies carried out in areas with limited refrigeration and freezing storage. In addition, urinary PAH biomarkers are hydroxylated metabolites after phase-I metabolism of the parent PAHs. In contrast, levoglucosan and methoxyphenol are measured in urine and present in smoke in the same form. Therefore, when using urinary OH-PAHs as exposure biomarkers, the samples are unlikely to be compromised by potential contamination during sample collection, transportation, and storage.

This study has several limitations. First, total PAH concentrations in air during the exposure period could not be measured in this study. PAHs are distributed into both gaseous and particle phases in air. The PM2.5-bound PAHs measured in this study only represented a portion of total PAHs in air. Second, we were only able to have nine participants completing this study, owing to limited resources, logistical considerations, and the burden on the participants. A larger sample size would give more power to this study. Third, we analyzed a subset of 13 urine voids per subject, and were unable to analyze every urine void collected by the subjects owing to budget limitation. Measuring all samples would provide more detail to the excretion profile.

In conclusion, urinary PAH metabolite levels increased in participants who were exposed experimentally to woodsmoke for 2 h. Most OH-PAHs, with the exception of 1-PYR, correlated with air pollutants on personal PM2.5 samples collected during the 2-h exposure period. Hence, 1-PYR is not the best biomarker for inhalation exposure to woodsmoke, compared with the metabolites of naphthalene, fluorene, and phenanthrene; this is especially true in low to modest exposure scenarios. To assess acute or episodic exposure to woodsmoke, collecting multiple urine samples during a window of time, for example, 0–12 h post exposure, is more appropriate than a spot sample. Among the three classes of urinary woodsmoke biomarkers, OH-PAHs and methoxyphenols demonstrated comparable sensitivity whereas levoglucosan did not show anticipated responses after the exposure. All biomarker groups are not specific to woodsmoke and have other potential sources, which can be minimized with careful control or avoidance of alternative sources, for example, diet, smoking, and so on. Furthermore, the stability of the conjugated OH-PAHs in urine and minimal contamination risk during sample collection, transportation, and storage make these PAH metabolites especially suitable under suboptimal sampling and storage conditions, like in epidemiological studies in less developed areas, as is common with stove intervention programs.

References

Rehfuess E, Mehta S, Pruss-Ustun A . Assessing household solid fuel use: multiple implications for the Millennium Development Goals. Environ Health Perspect 2006; 114: 373–378.

Shah AS, V, Langrish JP, Nair H, McAllister DA, Hunter AL, Donaldson K et al. Global association of air pollution and heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2013; 382: 1039–1048.

Bell ML, Zanobetti A, Dominici F . Evidence on vulnerability and susceptibility to health risks associated with short-term exposure to particulate matter: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2013; 178: 865–876.

ATSDR. Toxicological Profile for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. 1995. Available from http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp69.pdf. Accessed 22 January 2014.

IARC. A review of human carcinogens: chemical agents and related occupations.in IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans Volume 100F.Lyon, France. Available from http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Monographs/vol100F/. Accessed 14 June 2014.

Naeher LP, Brauer M, Lipsett M, Zelikoff JT, Simpson CD, Koenig JQ et al. Woodsmoke health effects: A review. Inhal Toxicol 2007; 19: 67–106.

Kurmi OP, Devereux GS, Smith WC, Semple S, Steiner MF, Simkhada P et al. Reduced lung function due to biomass smoke exposure in young adults in rural Nepal. Eur Respir J 2013; 41: 25–30.

Kurmi OP, Semple S, Simkhada P, Smith WC, Ayres JG . COPD and chronic bronchitis risk of indoor air pollution from solid fuel: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2010; 65: 221–228.

Pope DP, Mishra V, Thompson L, Siddiqui AR, Rehfuess EA, Weber M et al. Risk of low birth weight and stillbirth associated with indoor air pollution from solid fuel use in developing countries. Epidemiol Rev 2010; 32: 70–81.

Boy E, Bruce N, Delgado H . Birth weight and exposure to kitchen wood smoke during pregnancy in rural Guatemala. Environ Health Perspect 2002; 110: 109–114.

Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Vander HS, Murray CJ . Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet 2002; 360: 1347–1360.

Clark ML, Peel JL, Burch JB, Nelson TL, Robinson MM, Conway S et al. Impact of improved cookstoves on indoor air pollution and adverse health effects among Honduran women. Int J Environ Health Res 2009; 19: 357–368.

Cynthia AA, Edwards RD, Johnson M, Zuk M, Rojas L, Jimenez RD et al. Reduction in personal exposures to particulate matter and carbon monoxide as a result of the installation of a Patsari improved cook stove in Michoacan Mexico. Indoor Air 2008; 18: 93–105.

Rylance J, Gordon SB, Naeher LP, Patel A, Balmes JR, Adetona O et al. Household air pollution: a call for studies into biomarkers of exposure and predictors of respiratory disease. Am J Physiol -Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2013; 304: L571–L578.

McCracken JP, Smith KR, Diaz A, Mittleman MA, Schwartz J . Chimney stove intervention to reduce long-term wood smoke exposure lowers blood pressure among Guatemalan women. Environ Health Perspect 2007; 115: 996–1001.

Pirkle JL, Needham LL, Sexton K . Improving exposure assessment by monitoring human tissues for toxic chemicals. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol 1995; 5: 405–424.

Simpson CD, Naeher LP . Biological monitoring of wood-smoke exposure. Inhal Toxicol 2010; 22: 99–103.

Naeher LP, Barr DB, Adetona O, Simpson CD . Urinary levoglucosan as a biomarker for woodsmoke exposure in wildland firefighters. Int J Occup Environ Health 2013; 19: 304–310.

Bergauff MA, Ward TJ, Noonan CW, Migliaccio CT, Simpson CD, Evanoski AR et al. Urinary levoglucosan as a biomarker of wood smoke: results of human exposure studies. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2010; 20: 385–392.

Migliaccio CT, Bergauff MA, Palmer CP, Jessop F, Noonan CW, Ward TJ . Urinary levoglucosan as a biomarker of wood smoke exposure: observations in a mouse model and in children. Environ Health Perspect 2009; 117: 74–79.

Dills RL, Zhu X, Kalman DA . Measurement of urinary methoxyphenols and their use for biological monitoring of wood smoke exposure. Environ Res 2001; 85: 145–158.

Li Z, Sandau CD, Romanoff LC, Caudill SP, Sjodin A, Needham LL et al. Concentration and profile of 22 urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites in the US population. Environ Res 2008; 107: 320–331.

Health Canada. Second report on human biomonitoring of environmental chemicals in Canada. Results of the Canadian Health Measures Survey Cycle 2 (2009-2011). 2013. Available from www.healthcanada.gc.ca/biomonitoring. Accessed 16 June 2014.

Strickland P, Kang D, Sithisarankul P . Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites in urine as biomarkers of exposure and effect. Environ Health Perspect 1996; 104 (Suppl 5): 927–932.

Angerer J, Mannschreck C, Gundel J . Biological monitoring and biochemical effect monitoring of exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 1997; 70: 365–377.

Mucha AP, Hryhorczuk D, Serdyuk A, Nakonechny J, Zvinchuk A, Erdal S et al. Urinary 1-hydroxypyrene as a biomarker of PAH exposure in 3-year-old Ukrainian children. Environ Health Perspect 2006; 114: 603–609.

Hansen AM, Mathiesen L, Pedersen M, Knudsen LE . Urinary 1-hydroxypyrene (1-HP) in environmental and occupational studies-A review. Int J Hyg Environ Health 2008; 211: 471–503.

Torres-Dosal A, Perez-Maldonado IN, Jasso-Pineda Y, Salinas RIM, Alegria-Torres JA, Diaz-Barriga F . Indoor air pollution in a Mexican indigenous community: Evaluation of risk reduction program using biomarkers, of exposure and effect. Sci Total Environ 2008; 390: 362–368.

Siwinska E, Mielzynska D, Bubak A, Smolik E . The effect of coal stoves and environmental tobacco smoke on the level of urinary 1-hydroxypyrene. Mutat Res 1999; 445: 147–153.

Li Z, Sjodin A, Romanoff LC, Horton K, Fitzgerald CL, Eppler A et al. Evaluation of exposure reduction to indoor air pollution in stove intervention projects in Peru by urinary biomonitoring of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites. Environ Int 2011; 37: 1157–1163.

Riojas-Rodriguez H, Schilmann A, Marron-Mares AT, Masera O, Li Z, Romanoff L et al. Impact of the improved patsari biomass stove on urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon biomarkers and carbon monoxide exposures in rural Mexican women. Environ Health Perspect 2011; 119: 1301–1307.

Dills RL, Paulsen M, Ahmad J, Kalman DA, Elias FN, Simpson CD . Evaluation of urinary methoxyphenols as biomarkers of woodsmoke exposure. Environ Sci Technol 2006; 40: 2163–2170.

Li Z, Romanoff LC, Trinidad DA, Hussain N, Jones RS, Porter EN et al. Measurement of urinary monohydroxy polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons using automated liquid-liquid extraction and gas chromatography/isotope dilution high-resolution mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 2006; 78: 5744–5751.

Li Z, Romanoff L, Bartell S, Pittman EN, Trinidad DA, McClean M et al. Excretion profiles and half-lives of ten urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites after dietary exposure. Chem Res Toxicol 2012; 25: 1452–1461.

Bartell SM . Bias in half-life estimates using log concentration regression in the presence of background exposures, and potential solutions. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2012; 22: 299–303.

CDC. National report on human exposure to environmental chemicals, updated tables, August 2014. 2014. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport/. Accessed 12 November 2014.

Maroni M, Colosio C, Ferioli A, Fait A . Biological monitoring of pesticide exposure: a review. Toxicology 2000; 143: 5–118.

Pahari AK, Majumdar S, Mandal TK, Chakraborty AK, Bhattacharyya A, Chowdhury A . Toxico-kinetics, recovery, and metabolism of napropamide in goats following a single high-dose oral administration. J Agric Food Chem 2001; 49: 1817–1824.

Walle T, Gaffney TE . Propranolol metabolism in man and dog: mass spectrometric identification of six new metabolites. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1972; 182: 83–92.

Preuss R, Angerer J, Drexler H . Naphthalene - an environmental and occupational toxicant. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2003; 76: 556–576.

Yang M, Koga M, Katoh T, Kawamoto T . A study for the proper application of urinary naphthols, new biomarkers for airborne polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol 1999; 36: 99–108.

Re-Poppi N, Santiago-Silva M . Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and other selected organic compounds in ambient air of Campo Grande City, Brazil. Atmos Environ 2005; 39: 2839–2850.

Sitaras IE, Bakeas EB, Siskos PA . Gas/particle partitioning of seven volatile polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in a heavy traffic urban area. Sci Total Environ 2004; 327: 249–264.

Akyuz M, Cabuk H . Gas-particle partitioning and seasonal variation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the atmosphere of Zonguldak, Turkey. Sci Total Environ 2010; 408: 5550–5558.

Li Z, Mulholland JA, Romanoff LC, Pittman EN, Trinidad DA, Lewin MD et al. Assessment of non-occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons through personal air sampling and urinary biomonitoring. J Environ Monit 2010; 12: 1110–1118.

Kato M, Loomis D, Brooks LM, Gattas GFJ, Gomes L, Carvalho AB et al. Urinary biomarkers in charcoal workers exposed to wood smoke in Bahia State, Brazil. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004; 13: 1005–1012.

Bieniek G . The presence of 1-naphthol in the urine of industrial workers exposed to naphthalene. Occup Environ Med 1994; 51: 357–359.

St Helen G, Goniewicz ML, Dempsey D, Wilson M, Jacob P, III, Benowitz NL . Exposure and kinetics of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in cigarette smokers. Chem Res Toxicol 2012; 25: 952–964.

Sobus JR, Mcclean MD, Herrick RF, Waidyanatha S, Onyemauwa F, Kupper LL et al. Investigation of PAH biomarkers in the urine of workers exposed to hot asphalt. Ann Occup Hyg 2009; 53: 551–560.

Huang W, Smith TJ, Ngo L, Wang T, Chen H, Wu F et al. Characterizing and biological monitoring of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in exposures to diesel exhaust. Environ Sci Technol 2007; 41: 2711–2716.

Brzeznicki S, Jakubowski M, Czerski B . Elimination of 1-hydroxypyrene after human volunteer exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 1997; 70: 257–260.

Lafontaine M, Payan JP, Delsaut P, Morele Y . Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon exposure in an artificial shooting target factory: assessment of 1-hydroxypyrene urinary excretion as a biological indicator of exposure. Ann Occup Hyg 2000; 44: 89–100.

Needham LL, Barr DB, Calafat AM . Characterizing children's exposures: beyond NHANES. Neurotoxicology 2005; 26: 547–553.

Simoneit BRT, Schauer JJ, Nolte CG, Oros DR, Elias VO, Fraser MP et al. Levoglucosan, a tracer for cellulose in biomass burning and atmospheric particles. Atmos Environ 1999; 33: 173–182.

Fraser MP, Lakshmanan K . Using levoglucosan as a molecular marker for the long-range transport of biomass combustion aerosols. Environ Sci Technol 2000; 34: 4560–4564.

Hawthorne SB, Miller DJ, Barkley RM, Krieger MS . Identification of methoxylated phenols as candidate tracers for atmospheric wood smoke pollution. Environ Sci Technol 1988; 22: 1191–1196.

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants for their time and devotion, Scott Bartell for the pharmacokinetic model code, and Dan Middleton and Donald Hilton for commenting on the manuscript. This work was funded in part by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (#R03-OH007656). EAR is supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (T32ES015459). The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Trinidad, D., Pittman, E. et al. Urinary polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon metabolites as biomarkers to woodsmoke exposure — results from a controlled exposure study. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 26, 241–248 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/jes.2014.94

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/jes.2014.94

- Springer Nature America, Inc.

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Disturbance of OH-PAH metabolites in urine induced by single PAH lab exposure

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

-

Development of LC-HRMS untargeted analysis methods for nasal epithelial lining fluid exposomics

Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology (2022)

-

Health effects of exposure to diesel exhaust in diesel-powered trains

Particle and Fibre Toxicology (2019)

-

Urinary hydroxypyrene determination for biomonitoring of firefighters deployed at the Fort McMurray wildfire: an inter-laboratory method comparison

Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry (2019)

-

Health risk assessment on human exposed to heavy metals in the ambient air PM10 in Ahvaz, southwest Iran

International Journal of Biometeorology (2018)