Abstract

Background:

An association between depression and obesity is well recognised, but longitudinal studies of depressive symptoms in adolescents as a predictor of body composition are lacking.

Objective:

We examined depressive symptoms at age 14, 17 and 20 years as predictors of lean, fat and bone mass at age 20 years in a birth cohort.

Subjects/Methods:

In 1161 participants (569 females) in the Western Australia Pregnancy Cohort (Raine) Study, depressive symptoms were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory for Youth at age 14 and 17 years, and the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale 21 at age 20 years. Participants were further classified into two trajectories using latent class analysis: no/transient and persistent/recurrent depression. At age 20 years, lean body mass (LBM), fat body mass (FBM) and total body bone mass were measured by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry.

Results:

In females, accounting for age and lifestyle factors, depression scores at age 14 and 20 years were positively associated with body weight, body mass index (BMI), FBM and % FBM (r=0.110–0.184, P<0.05) but negatively correlated with % LBM (r=−0.120, P<0.05) at age 20 years. Females in the persistent/recurrent depression trajectory (n=99) had significantly higher body weight (+5.1 kg), BMI (+1.8 kg m−2), FBM (+3.9 kg) and % FBM (+2.2%) and significantly lower % LBM (−2.2%) at age 20 years than those with no/transient depression (n=470; all P<0.05). In males, depression scores at age 17 and 20 years were negatively associated with LBM but not weight or BMI, and depression trajectory was not a predictor of body composition at age 20 years. Depression scores and trajectories did not predict bone mass in either males or females.

Conclusions:

Depressive symptoms and persistent/recurrent depression in adolescence are predictors of greater adiposity at age 20 years in females, but not males, but do not predict bone mass in either gender.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The association of depression and obesity has been studied in a number of studies. It has been suggested that depression may cause obesity via binge eating, increased consumption of carbohydrates and fat foods, reduced physical activity level and increased cortisol secretion.1, 2, 3 On the other hand, obesity might also be a cause of depression owing to psychological disorders or low self-esteem resulted from negative body image.4 Less is known on the association of depression with the composition of body mass, as the majority of studies evaluating these associations at adolescence and young adulthood used body mass index (BMI) as the indicator of body fatness,1, 5, 6 and few assessed lean and fat mass using techniques such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). A cross-sectional study of 2406 participants aged 18–69 years in the American National Health and Nutrition Examination (NHANES 2005–2006) survey showed that moderate-to-severe depression in men and severe depression in women was associated with reduced percentage lean body mass (% LBM) and increased percentage fat body mass (% FBM).7 The only study in children and youth that measured body composition using DXA was of selected participants seeking obesity treatment,8 and there has been no prospective study in the general population evaluating whether depression symptoms in adolescents predict body composition in early adulthood.

In middle-aged and older adults, an inverse association between depression or depressive symptoms and bone mineral density (BMD) of spine and hip was observed in a cross-sectional study.9 Two cross-sectional studies in young adults showed that major depressive episode and dysthymia10 or moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms11 was related to reduced bone mass as measured by DXA BMD or heel ultrasound stiffness index in males but not in females. By contrast, in premenopausal women, a case–control study showed that major depression disorder was associated with lower BMD at hip and spine.12 It has been suggested that depression during adolescence and early adulthood may interfere with the achievement of optimal peak bone mass,12 but longitudinal studies are lacking.

The Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort (Raine) Study is a large prospective cohort of pregnancy, childhood, adolescence and early adulthood in Western Australia13 and has data on depressive symptoms in offspring studied at 14, 17 and 20 years. Considering the negative health consequences of high body fat, reduced muscle mass and low bone density in later life such as obesity, sarcopenia and osteoporosis, the aims of this study were to examine depressive symptoms at 14, 17 and 20 years and their trajectories as predictors of lean, fat and bone mass in early adulthood (20 years) in the Raine cohort.

Subjects and methods

Participants

This longitudinal, prospective study included data from 1161 offspring (592 males and 569 females) from the Western Australian Pregnancy Cohort (Raine) Study. The Raine study recruited 2900 pregnant women from the antenatal clinic at King Edward Memorial Hospital and nearby private clinics in Perth, Western Australia between May 1989 and November 1991. Inclusion criteria were a gestational age between 16 and 20 weeks, English language skills sufficient to understand the study demands, an expectation to deliver at King Edward Memorial Hospital and an intention to remain in Western Australia to enable future follow-up of their child.14 All offspring have been invited to attend periodic follow-up surveys. Compared with the general Western Australian population, the Raine cohort at birth was characterized by higher proportions of high-risk births and fathers employed in managerial and professional positions, but comparison of participants remaining in the study at the 14-year follow-up suggested that attrition resulted in a cohort comparable with the general population.15 The current study is restricted to offspring who underwent whole-body DXA scanning as part of the 20-year follow-up visit and had at least one depressive symptoms assessment at 14, 17 and 20 years. The study at each follow-up was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of Princess Margaret Hospital (year 14 and 17) and University of Western Australia (year 20). Written informed consent was obtained from the primary caregiver at ages 14 and 17 years, and from each participant at age 20 years.

Depressive symptoms at 14, 17 and 20 years

Depressive symptoms at ages 14 and 17 years were assessed using the Beck Depression Inventory for Youth (BDI-Y),16 which is an adolescent adaptation of the adult Beck Depression Inventory-2(ref. 17) and has excellent psychometric properties.16, 18 The possible score range is from 0 to 63. With participants moving to early adulthood, depressive symptoms at age 20 years were assessed using the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale 21 (DASS-21), which is the short form of the DASS-42, a self-report scale designed to measure the negative emotional states of depression, anxiety and stress.19 The DASS-21 has internal consistency and concurrent validity in acceptable-to-excellent ranges.20 The possible score range for the depression scale is from 0 to 42. For both BDI-Y and DASS-21, a higher score indicates more severe depressive symptoms.

Latent class analysis was used to estimate trajectories of depression using an ordinal logit model, in which BDI-Y and DASS depression scores were categorised into three groups—normal range, mild depression and moderate-to-severe depression using the relevant cutoff points for BDI-Y score (⩽16, 17–20 and ⩾ 21)16 and DASS depression score (⩽9, 10–13 and ⩾ 14).19 Sex was used as an active covariate in the models and a series of models between 1 and 3 trajectories were estimated. Two trajectories were chosen based on a combination of statistical criteria, parsimony and interpretability.21 Participants were assigned to the trajectory class for which they had the highest posterior probability of membership. The two trajectories identified were no/transient depression (most of the BDI-Y or DASS depression scores classified as normal range) and persistent/recurrent depression (most of the BDI-Y and DASS depression scores classified as mild or moderate-to-severe depression).

Whole-body DXA at 20 years

Whole-body scanning was performed in offspring at the 20-year follow-up visit using DXA on a Norland XR-36 densitometer (Norland Medical Systems, Inc., Fort Atkinson, WI, USA), according to the manufacturer-recommended procedures. Analysis of scans was performed using the built-in machine software (version 4·3·0), which provided estimates of LBM (bone free; kg), FBM (kg), as well as whole body BMC (g) and areal BMD (g cm−2). Percentage LBM was calculated as (LBM/total mass) × 100 and percentage FBM as (FBM/total mass) × 100. Daily calibration was performed prior to each scanning session, and the interscan coefficient of variation was <2%.

Other assessments

At 14, 17 and 20 years, body weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg with subjects dressed in light clothes, and height was measured with a stadiometer (Holtain Ltd., Crosswell, Crymych, Pembs., UK) to the nearest 0.1 cm. BMI was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2. At 20 years, a validated semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire from the Cancer Council Victoria22 was used to assess dietary intake, including energy, calcium and alcohol intake at 20 years. Physical activity level at 20 years was assessed using the short-form International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) and categorised as low, medium and high according to the IPAQ scoring protocol (IPAQ (http://www.ipaq.ki.se/scoring.htm)). The IPAQ questionnaire asks the participants the time they spent being physically active in the past 7 days and has been shown to produce repeatable data (r=0.80), with a criterion validity (r=0.30) similar to other self-report validation studies when assessed against accelerometer data.23 Information on smoking habit at 20 years was collected using a questionnaire.

Data analysis

Variables are presented as mean (s.d.) unless otherwise stated. The normality of continuous variables was checked through the construction of histograms. Comparisons between male and female offspring were made using Student’s t-test and chi-square test. Pearson’s correlation analysis was used to calculate the correlation coefficients between BDI-Y score at 14 and 17 years and DASS depression score at 20 years with body weight and BMI at each time point, and body composition and bone measures at 20 years in each gender. Further analysis were made by partial correlation adjusting for covariates, including age, smoking, alcohol intake, physical activity level, total energy intake (or calcium intake for models for BMC and BMD), height (for models for LBM, FBM and BMC only) and body weight (for models for BMD only) at 20 years. The associations of BDI-Y scores at 14 and 17 years with body weight, BMI and body composition measures at 20 years were evaluated further by including body weight or BMI at 14 or 17 years (respectively) as covariate in the models. Student’s t-test and analysis of covariance (adjusted for covariates as listed above) were used to compare the two depression trajectories (no/transient, persistent/recurrent). The homogeneity of variance of each model was checked by Levene's Test. Statistical significance level was set at P<0.05 (two tailed). All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS (version 22, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA) and R (version 3.0.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Participant characteristics at 14, 17 and 20 years are shown in Table 1. At all three visits, males were heavier, but their BMI was not significantly different from that of females. There was an increase in BMI with increased age in both genders. Using the relevant cutoff values for the BDI-Y and DASS depression scores, at 14, 17 and 20 years the percentage of participants classified as having mild depressive symptoms was 2.7, 5.8 and 10.9% for males and 6.2, 8.0 and 11.2% for females, and the percentage classified as having moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms was 1.5, 4.0 and 13.8% for males and 5.2, 13.4 and 21.6% for females, respectively. This gender difference was statistically significant at each time point (all P<0.01 by chi-square test).

Depression symptoms at 14, 17 and 20 years and body composition and bone mass

In males, BDI-Y scores at 14 and 17 years and DASS depression score at 20 years did not have significant correlation with body weight and BMI measured at the same follow-up or 20 years (r=−0.045 to 0.007, all P>0.10). BDI-Y score at 17 years and DASS depression score at 20 years showed significant negative correlations with LBM and % LBM and positive correlation with % FBM at 20 years (Table 2). In the partial correlation analyses adjusted for covariates including age, smoking, alcohol intake, physical activity level, total energy intake and height (for models for LBM and FBM only) at 20 years, only the correlation with LBM remained significant (Table 2).

In females, BDI-Y score at 14 years had significant positive correlation with body weight and BMI measured at the same time point (r=0.099 and 0.107, respectively, P<0.05), and BDI-Y score at 17 years had significant positive correlation with body weight measured at 17 years (r=0.098, P=0.039). BDI-Y score at 14 years and DASS depression score at 20 years showed significant positive correlations with body weight, BMI, FBM and % FBM and negative correlation with % LBM at 20 years (Table 2). In the partial correlation analyses adjusted for covariates including age, lifestyle and anthropometric factors at 20 years, all these correlations remained significant, and 17-year BDI-Y score also showed significant positive correlation with body weight, BMI and FBM at 20 years (Table 2). However, in further models where body weight or BMI at the time of BDI-Y assessment was also included as covariate, the correlations of 14- or 17-year BDI-Y scores with body weight, BMI and FBM at 20 years were no longer significant (r=0.064–0.087, all P>0.05).

There were no significant relationships between depression scores at any age and total body BMC or BMD at 20 years in either males or females (Table 2).

Depression trajectories from 14 to 20 years and body composition and bone mass

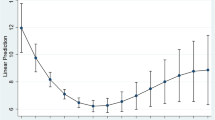

Figure 1 depicts the changes in depression scores from 14 to 20 years in the two trajectory classes (no/transient, persistent/recurrent). Table 3 shows the comparisons between the two trajectory classes in body weight at each time point and body composition and bone variables at 20 years. In males, there were no significant differences in weight, BMI, lean body mass, fat mass or bone mass between the two trajectory classes. Females in the persistent/recurrent depression trajectory class had significantly higher weight at age 14 (by 4.7 kg), 17 (by 3.9 kg) and 20 (by 4.5 kg) years and greater BMI (by 1.7 kg m−2) and FBM (by 3.4 kg) at age 20 years than those in the no/transient depression group, but weight gain between age 14 or 17 and 20 years did not differ significantly by trajectory. There were no significant differences in BMC or BMD between trajectory classes in females. Further analysis by analysis of covariance including the covariates of age, lifestyle and anthropometric factors at 20 years gave very similar results, and the persistent/recurrent depression group also had significantly lower % LBM (−2.2%) and significantly higher % FBM (+2.2%; Table 3).

Mean depression scores at 14, 17 (BDI-Y) and 20 years (DASS-21) for the two depression trajectories derived from latent class analysis. Please note that the potential highest score (63 vs 42) and the cutoff for mild (17 vs 10) and moderate-to-severe (21 vs 14) depression are both higher for BDI-Y compared with DASS-21.

Discussion

In this cohort study of young adults from adolescence to early adulthood, the prevalence of depression using standard questionnaires was higher in females than in males at 14, 17 and 20 years of age, and there was an apparent sex difference in the relationships between depressive symptoms and body composition measured at age 20 years. In males, depression scores at age 17 and 20 years had an inverse relationship with LBM, but no significant association with body weight or BMI. In females, depression scores at 14 and 20 years were positively associated with body weight, BMI, FBM and % FBM and negatively associated with % LBM. Depression scores were not significantly associated with total body bone mass in males or females. When analysed by trajectory of depression, females with persistent/recurrent depression had significantly higher body weight, BMI and FBM at age 20 years than those with no/transient depression, whereas bone mass did not differ by trajectory class. In males, there were no significant differences in body composition and bone measures between trajectory classes.

Because depression was less common in males, we cannot be sure whether these results reflect a biological difference between sexes in the relationship between depression and body composition or simply lack of statistical power for analysis of males. However, our data are consistent with previous cross-sectional studies in preadolescent American children24 and Chinese adolescents,25 which found a modest association between depressive symptoms and BMI in girls (r=0.14 and 0.27, respectively) but not boys. A meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies in community-based adults also showed a significant association between depression and obesity in females but a smaller non-significant association in males.26 These findings indicate the importance of assessing body composition when studying the associations between depressive symptoms and obesity across the sexes, as the influence in males appears to be on the changes in body composition (reduced lean body mass) rather than on total body mass.

In addition, we found that depression symptoms at age 14 years were related to increased body weight in females, which was carried onto early adulthood. Furthermore, females in the trajectory class of persistent/recurrent depression from 14 to 20 years had higher body weight, BMI and fat mass at 20 years compared with those with no/transient depression, but weight change did not differ according to trajectory, suggesting that higher body weight at 14 and 17 years predicted greater fatness at age 20 years. Overall, the results emphasize the importance of managing both depression and obesity during adolescence.

Our results on the relationship between depressive symptoms and body composition are broadly consistent with cross-sectional analyses from NHANES 2005–2006 in adults aged 18–69 years, in which moderate-to-severe depression was associated with reduced LBM and % LBM and increased % FBM in men, whereas severe depression was associated with reduced % LBM and increased % FBM but not LBM in women.7 This suggests that, in males, depression is associated with reduced lean body mass, whereas in females it is associated with increased FBM, which in turn results in reduced % LBM. The associations of depression and increased body fat and/or decreased lean body mass could not be fully explained by common lifestyle factors such as physical activity, energy intake, smoking and alcohol consumption in the present study or in previous studies in children27 and adults.7 Depression has been shown to be associated with low physical activity levels,28 and physical exercise interventions in depressive disorders have been reported to have moderate-to-large antidepressant effects.29 In addition, a structured supervised training programme has been shown to improve aerobic capacity in inpatients with major depression disorders.30 Although we adjusted for physical activity, the data were limited to self-reported IPAQ data at age 20 years, and it is possible that different patterns of physical activity mediated or moderated the associations we identified between depression and body composition. It is also possible that depression leads to increased body fatness through alteration of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis function and increased cortisol secretion,3, 31 as well as by impacting on eating behaviour. The mechanism underlying the association between depression and reduced muscle mass in young men is not entirely clear; it could arise from reduced physical activity, increased cortisol secretion, reduced androgen secretion or other mechanisms. In older men, depression is associated with reduced serum albumin7 and testosterone levels.32

We did not observe any significant association between depressive symptoms at 14, 17 and 20 years, or trajectory classes for depression, and bone mass measured at 20 years in male or female participants. Consistent with this, a previously study showed that depressive symptoms measured using the BDI-II at 13 and 17 years were not associated with forearm BMD measured at each time point or the change in BMD.33 In contrast, other studies have shown an inverse association between depression or depressive symptoms and BMD in middle-aged and older adults,9 young men aged 20–39(ref. 10) and 29–32 years11 and premenopausal women.12 It could be that adolescent depression does not affect bone mass accrual, but depression contributes to bone loss in later adulthood. Our study is the only study to assess peak bone mass at an age when participants have reached skeletal maturity34 and are yet to experience age-related bone loss. In the two previous studies of young adults, the significant associations with BMD were observed in males (but not females) with major depression episode/dysthymia10 or moderate-to-severe depression,11 whereas in our study, only a low percentage of male participants had scores in the moderate-to-severe depression category.

Strengths of our study include its large sample size, longitudinal assessment of depressive symptoms using standard questionnaires at 14, 17 and 20 years, assessment of bone density by DXA at skeletal maturity and use of trajectory analysis for depression scores. Our study also has limitations. First, its observational nature means we cannot assume that the relationships between depressive symptoms and body composition are causal. Furthermore, if there is a causal relationship, we cannot be certain whether depression results in increased fat mass or vice versa or whether there is bidirectional relationship as indicated by previous longitudinal studies in adults.35 Most of the participants were Caucasian, and the study findings may not be applicable to other ethnic groups. Physical activity data were only available at age 20 years and were limited to self-report. We used two different measures of depression, consistent with the transition of our participants from adolescence to adulthood. Although age-appropriate measures are a strength of the research, different questionnaires complicate assessment of changes in depression over time. We attempted to overcome this by using recommended cut points for mild and moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms (specific to each measure) in our latent class analyses.

Conclusions

In this cohort of young adults, we observed that in females symptoms of depression during adolescence and persistent/recurrent depression from age 14 to 20 years were associated with higher body weight, BMI and fat mass at age 20 years. In males, depressive symptoms were negatively associated with lean mass, but depression trajectory did not predict body composition at age 20 years. Depression scores and trajectories did not predict bone mass in males or females. Considering the negative health consequences of high body fat and reduced muscle mass such as obesity and sarcopenia in later life, effective management of depression and obesity in adolescence and early adulthood could confer metabolic benefits in later adulthood.

References

Hasler G, Pine DS, Kleinbaum DG, Gamma A, Luckenbaugh D, Ajdacic V et al. Depressive symptoms during childhood and adult obesity: the Zurich Cohort Study. Mol Psychiatry 2005; 10: 842–850.

Van Strien T, Schippers GM, Cox WM . On the relationship between emotional and external eating behavior. Addict Behav 1995; 20: 585–594.

Heuser I . Anna-Monika-Prize paper. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system in depression. Pharmacopsychiatry 1998; 31: 10–13.

Anderson SE, Cohen P, Naumova EN, Jacques PF, Must A . Adolescent obesity and risk for subsequent major depressive disorder and anxiety disorder: prospective evidence. Psychosom Med 2007; 69: 740–747.

Richardson LP, Davis R, Poulton R, McCauley E, Moffitt TE, Caspi A et al. A longitudinal evaluation of adolescent depression and adult obesity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2003; 157: 739–745.

Goodman E, Whitaker RC . A prospective study of the role of depression in the development and persistence of adolescent obesity. Pediatrics 2002; 110: 497–504.

Li Y, Meng L, Li Y, Sato Y . Depression-related differences in lean body mass distribution from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2006. J Affect Disord 2014; 157: 1–7.

Morrison KM, Shin S, Tarnopolsky M, Taylor VH . Association of depression and health related quality of life with body composition in children and youth with obesity. J Affect Disord 2015; 172: 18–23.

Cizza G, Primma S, Coyle M, Gourgiotis L, Csako G . Depression and osteoporosis: a research synthesis with meta-analysis. Horm Metab Res 2010; 42: 467–482.

Mussolino ME, Jonas BS, Looker AC . Depression and bone mineral density in young adults: results from NHANES III. Psychosom Med 2004; 66: 533–537.

Oh SM, Kim HC, Kim KM, Ahn SV, Choi DP, Suh I . Association between depressive symptoms and bone stiffness index in young adults: the Kangwha study. PLoS One 2013; 8: e69929.

Eskandari F, Martinez PE, Torvik S, Phillips TM, Sternberg EM, Mistry S et al. Low bone mass in premenopausal women with depression. Arch Intern Med 2007; 167: 2329–2336.

McKnight CM, Newnham JP, Stanley FJ, Mountain JA, Landau LI, Beilin LJ et al. Birth of a cohort—the first 20 years of the Raine study. Med J Aust 2012; 197: 608–610.

Newnham JP, Evans SF, Michael CA, Stanley FJ, Landau LI . Effects of frequent ultrasound during pregnancy: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 1993; 342: 887–891.

Robinson M, Oddy WH, McLean NJ, Jacoby P, Pennell CE, de Klerk NH et al. Low-moderate prenatal alcohol exposure and risk to child behavioural development: a prospective cohort study. BJOG 2010; 117: 1139–1150.

Beck S, Beck AT, Jolly J . Beck Youth Inventory. Psychological Corporation: New York, USA, 2001.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK . Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd edn. The Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, USA, 1996.

Eack SM, Singer JB, Greeno CG . Screening for anxiety and depression in community mental health: the beck anxiety and depression inventories. Community Ment Health J 2008; 44: 465–474.

Lovibond SH, Lovibone PF . Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, 2nd edn. Psychology Foundation: Sydney, Australia, 1995.

Antony MM, Bieling PJ, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Swinson RP . Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychol Assess 1998; 10: 176–181.

Collins L, Lanza S . Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis: with Applications in the Social, Behavioural and Health Sciences. John Wiley and Sons Inc.: Hoboken, USA, 2010.

Hodge A, Patterson AJ, Brown WJ, Ireland P, Giles G . The Anti Cancer Council of Victoria FFQ: relative validity of nutrient intakes compared with weighed food records in young to middle-aged women in a study of iron supplementation. Aust NZ J Public Health 2000; 24: 576–583.

Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003; 35: 1381–1395.

Erickson SJ, Robinson TN, Haydel KF, Killen JD . Are overweight children unhappy?: body mass index, depressive symptoms, and overweight concerns in elementary school children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000; 154: 931–935.

Xie B, Chou CP, Spruijt-Metz D, Liu C, Xia J, Gong J et al. Effects of perceived peer isolation and social support availability on the relationship between body mass index and depressive symptoms. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005; 29: 1137–1143.

de Wit L, Luppino F, van Straten A, Penninx B, Zitman F, Cuijpers P . Depression and obesity: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiatry Res 2010; 178: 230–235.

Pine DS, Goldstein RB, Wolk S, Weissman MM . The association between childhood depression and adulthood body mass index. Pediatrics 2001; 107: 1049–1056.

Stubbs B, Koyanagi A, Schuch FB, Firth J, Rosenbaum S, Veronese N et al. Physical activity and depression: a large cross-sectional, population-based study across 36 low- and middle-income countries. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2016; 134: 546–556.

Josefsson T, Lindwall M, Archer T . Physical exercise intervention in depressive disorders: meta-analysis and systematic review. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2014; 24: 259–272.

Kerling A, von Bohlen A, Kuck M, Tegtbur U, Grams L, Haufe S et al. Exercise therapy improves aerobic capacity of inpatients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav 2016; 6: e00469.

Forbes EE, Williamson DE, Ryan ND, Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Dahl RE . Peri-sleep-onset cortisol levels in children and adolescents with affective disorders. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 59: 24–30.

Shores MM, Sloan KL, Matsumoto AM, Moceri VM, Felker B, Kivlahan DR . Increased incidence of diagnosed depressive illness in hypogonadal older men. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61: 162–167.

Lourenco S, Lucas R, da Silva DF, Ramos E, Barros H . Depressive symptoms are not associated with forearm bone accrual during adolescence. Arch Osteoporos 2014; 9: 173.

Baxter-Jones AD, Faulkner RA, Forwood MR, Mirwald RL, Bailey DA . Bone mineral accrual from 8 to 30 years of age: an estimation of peak bone mass. J Bone Miner Res 2011; 26: 1729–1739.

Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Penninx BW et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010; 67: 220–229.

Acknowledgements

We thank the efforts of the Raine Study participants and the Raine Study team for study co-ordination and data collection. Core funding for the Raine Study is provided by The University of Western Australia (UWA), Telethon Kids Institute, Raine Medical Research Foundation, UWA Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, Women’s and Infant’s Research Foundation, Curtin University and Edith Cowan University. The 20-year cohort follow-up assessment was funded by project grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and funding from the Lions Eye Institute, Nedlands, Western Australia. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research funded the DXA data collection (CIHR, Lye et al, MOP-82893).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, K., Allen, K., Mountain, J. et al. Depressive symptoms, body composition and bone mass in young adults: a prospective cohort study. Int J Obes 41, 576–581 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.214

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2016.214

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Non-melancholic depressive symptoms are associated with above average fat mass index in the Helsinki birth cohort study

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Association of depression, anxiety and menopausal-related symptoms with demographic, anthropometric and body composition indices in healthy postmenopausal women

BMC Women's Health (2021)