Abstract

Within the past 15 years, the endocannabinoid system (ECS) has emerged as a lipid signaling system critically involved in the regulation of energy balance, as it exerts a regulatory control on every aspect related to the search, the intake, the metabolism and the storage of calories. An overactive endocannabinoid cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) receptor signaling promotes the development of obesity, insulin resistance and dyslipidemia, representing a valuable pharmacotherapeutic target for obesity and metabolic disorders. However, because of the psychiatric side effects, the first generation of brain-penetrant CB1 receptor blockers developed as antiobesity treatment were removed from the European market in late 2008. Since then, recent studies have identified new mechanisms of action of the ECS in energy balance and metabolism, as well as novel ways of targeting the system that may be efficacious for the treatment of obesity and metabolic disorders. These aspects will be especially highlighted in this review.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The endocannabinoid system (ECS) monitors energy needs and metabolic responses in mammals by exerting a positive, anabolic control essentially on every aspect related to the intake and storage of calories. Accordingly, overactivity of the ECS is a characteristic feature of obesity and metabolic disorders in animals and humans.1, 2, 3, 4

This system, which is found in most mammalian cells and tissues, encompasses specific endogenous ligands, called endocannabinoids, their biosynthesis and degradation pathways and at least two specific receptor types named cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) and cannabinoid type 2 (CB2).5, 6 Both CB1 and CB2 are metabotropic receptors coupled to G proteins of the Gi/o type and their transduction systems include the modulation of ionic channels and of several intracellular pathways, such as the adenylate cyclase and the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways.7 The CB1 receptor is highly expressed throughout the central nervous system (CNS), including in neurons that regulate food intake, energy expenditure and reward-related responses, as well as in peripheral organs, such as liver, pancreas, muscle and adipose tissue.4, 8 Consequently, the CB1 receptor has been widely investigated as a target for the treatment of obesity and metabolic disorders.2, 9 Differently from CB1, the CB2 receptor is mainly found in immune cells and participate to the regulation of immune and inflammatory responses.7

Endocannabinoids are polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) derivatives generated on demand from cell membrane phospholipid precursors (Figure 1) that then act in an autocrine or paracrine manner on cannabinoid receptors.5, 6 The best characterized endocannabinoids are N-ethanolamide of arachidonic acid, also known as anandamide (AEA), and the glyceryl ester of arachidonic acid or 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) that are present in both central and peripheral neurons as well as in various types of parenchymal cells. Within the CNS, endocannabinoids classically work as retrograde neuromodulators, acting on CB1 receptors mainly located presynaptically and leading to the suppression of neurotransmitter release.10 Degradation of AEA and 2-AG requires their cellular reuptake and hydrolysis that is under the control of a fatty acid amide hydrolase for AEA and a monoacylglycerol lipase for 2-AG (Figure 1).5, 6

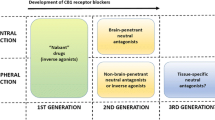

Initial findings demonstrating that pharmacological blockade of CB1 receptors inhibited food intake in rodents11, 12, 13 provided the impetus for testing CB1 receptor antagonists for the treatment of obesity. Indeed, chronic pharmacological blockade of CB1 in obese animal models and in obese patients decreases food intake and body weight, while improving lipid and glucose metabolism.2, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 Accordingly, mice lacking CB1 are lean and resistant to diet-induced obesity.19, 20 Unfortunately, the important psychiatric side effects of rimonabant, the first CB1 receptor antagonist approved for the treatment of obesity in several European countries, led to its withdrawal in late 2008. This event profoundly affected the pharmaceutical industry, with the discontinuation of development of all CB1 receptor antagonists that at the time were under clinical/preclinical investigation. However, it also stimulated new investigations into the mechanisms of action of the ECS in energy balance and metabolism, with the aim of generating new knowledge that would allow targeting this system in a more specific and selective manner. Since then, recent studies have identified a role for the ECS in the modulation of taste and olfaction, which critically affect feeding behavior, and in the regulation of fat intake and preference, and other investigations have detailed some of the CNS circuits engaged to regulate peripheral metabolism and the important function played by the peripheral ECS especially in the regulation of insulin sensitivity. In addition, the characterization of novel CB1 receptor antagonists that do not cause the well-known central side effects observed with rimonabant and the use of dietary strategies directly affecting endocannabinoid levels have reignited the interest around the ECS as therapeutic target.

Here we give an overview of the roles of the ECS in energy balance, discussing these latest advances and pinpointing the renewed interest of the field in this system and its therapeutic potential for the treatment of obesity and metabolic disorders.

Search strategy

A PubMed search of publications in English was conducted through the first week of December 2014. The following input was used for the search: cannabinoid AND (energy balance OR food intake OR obesity OR diabetes OR metabolic syndrome OR hypothalamus OR reward OR gut OR adipose tissue OR pancreas OR muscle OR liver OR diet). This search yielded more than 3500 potentially relevant articles. Additional articles were identified using the references listed in some of these articles. A total of 120 articles, the maximum allowed by the journal, were selected by the authors, who preferred recently published studies as well as articles that in the opinion of the authors were most significant and provided relevant information on the function of the ECS in the context of obesity and metabolic disease.

The ECS and the CNS regulation of energy balance and metabolism

The CNS coordinates the molecular, metabolic and behavioral mechanisms that guarantee that the different tissues get the nutrients they need when they need them. Within the CNS, the endocannabinoids act as retrograde neuromodulators able to inhibit both excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission by binding on presynaptic CB1 receptors.10 Thus, CB1 receptor signaling plays a key role in modulating neuronal activity, particularly in brain areas participating to the regulation of energy balance, such as the hypothalamus,21 the corticolimbic circuits,22 including the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and the ventral tegmental area, and the brainstem.23 Endocannabinoids are not stored in vesicles, but are produced and released ‘on demand’ only when and where they are needed. Consequently, they ideally inform about the incessant changes in energy availability. Not surprisingly, levels of endocannabinoids change in relation to the organism’s energy status, increasing with fasting and decreasing during refeeding in both the rat hypothalamus and limbic forebrain. Besides, when AEA and 2-AG are directly injected within the hypothalamus or the NAc, they increase food intake through a CB1 receptor-dependent mechanism.24, 25 Direct administration of AEA into the NAc shell increases the liking and the intake of a sucrose solution in rats in a CB1 receptor-dependent manner.26 Cannabinoids like Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol facilitate hedonic taste responses by increasing the dopamine release in the NAc shell after sucrose exposure.27 However, administration of the CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant prevents the increase in dopamine release in the NAc shell that is classically associated with the consumption of a novel palatable food.28 This evidence therefore suggests that the intake of palatable food increases endocannabinoids levels in the NAc shell and that such increase induces dopamine release in this brain area. As for the exact circuits determining this set of responses, it is likely that activation of ventral tegmental area dopaminergic neurons is achieved through an endocannabinoid-dependent activation of CB1 receptors on glutamatergic terminals that, by inhibiting GABAergic neurons projecting from the NAc to the ventral tegmental area, disinhibit dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area.29

Taste-related neuronal signals coming from the oral cavity are processed in the parabrachial nucleus and in the nucleus of the solitary tract in the hindbrain, where they are integrated with information coming from the gastrointestinal tract and modulate meal size and intermeal intervals.23 Endocannabinoids act through CB1 receptors located in the parabrachial nucleus to specifically increase intake of palatable food.30 Thus, as it happens in reward-related circuits, CB1 receptor signaling in the parabrachial nucleus facilitates the intake of food with hedonically positive sensory properties.30 Besides, food intake can also be favored by the action of CB1 receptor-dependent signaling on olfactory circuits. In fact, recent work by Soria-Gomez et al.31 has shown that fasting induces an increase in endocannabinoid levels in the olfactory bulb, activating CB1 receptors on olfactory cortex axon terminals and inhibiting granular cells in the olfactory bulb, increasing odor detection and food intake. Thus, although evidence is still missing, it is possible that deregulation of endocannabinoid-dependent taste-related and olfaction-related neuronal responses might have a role in obesity.

CB1 receptor mRNA is also found in several hypothalamic neuronal populations participating in the control of food intake and body weight,19 and the role of hypothalamic CB1 receptor signaling has been often investigated in association with the action of hormones known to play a role in energy balance, such as the anorexigenic hormone leptin and the orexigenic hormones glucocorticoids and ghrelin.

Leptin negatively regulates hypothalamic endocannabinoids levels, whereas genetic obese models with defective leptin production or signaling have increased hypothalamic endocannabinoid levels.32 Leptin prevents endocannabinoid synthesis by reducing intracellular calcium levels, a mechanism that explains leptin’s ability in inhibiting CB1-dependent activation of orexigenic melanin-concentrating hormone-expressing neurons in the lateral hypothalamus.33 However, leptin requires hypothalamic CB1 receptor signaling to exert its anorexigenic effect, as partial deletion of hypothalamic CB1 leads to the inability of the hormone to decrease food intake in mice.34 The ability of leptin to modulate food intake and metabolism actually depends on CB1 receptor signaling in specific neuronal populations and on the type of diet ingested. In fact, although deletion of CB1 receptors in steroidogenic factor-1 (SF1)-expressing neurons of the ventromedial hypothalamus increases sensitivity to the anorexigenic and metabolic effects of leptin during consumption of regular chow, lack of CB1 in SF1-expressing neurons causes molecular leptin resistance during consumption of a high-fat diet.35 In addition, recent studies have shown that presynaptic inputs expressing CB1 receptors change from being excitatory to inhibitory in hypothalamic orexin neurons when mice are fed a high-fat diet.36 This neuronal rewiring is in part due to impairment in leptin signaling and causes an increased activation of orexin neurons that in turn might increase food intake and body weight.36 Hence, this set of recent studies has further detailed the complex relationship between leptin and endocannabinoids within the hypothalamus.

Besides, an interaction also exists between leptin and glucocorticoids in the regulation of endocannabinoid synthesis in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN). Glucocorticoids act via a membrane receptor to quickly cause endocannabinoid-mediated suppression of synaptic excitation in PVN neurosecretory neurons.37 This mechanism is used by glucocorticoids to rapidly inhibit hypothalamic hormone secretion.37 Leptin blocks glucocorticoid-induced endocannabinoid biosynthesis and suppression of excitation in PVN neurons.38 Interestingly, hypothalamic increase in endocannabinoid signaling not only interferes with leptin’s actions, but can also lead to peripheral insulin resistance. Indeed, hyperinsulinemic, euglycemic clamp studies have demonstrated that central activation of CB1 receptors is sufficient to impair glucose homeostasis by hampering insulin action in the liver and the adipose tissue.39

Finally, the hormone ghrelin and the ECS share several commonalities in the regulation of energy balance. Endocannabinoids mediate the orexigenic effect of ghrelin, when this hormone is administered in the PVN.40 Ghrelin actually requires functional CB1 receptor signaling that in turn may recruit the AMP-activated protein kinase, an intracellular fuel gauge whose activity is necessary for the action of ghrelin within the hypothalamus.41, 42 Of note, AEA favors ghrelin synthesis and secretion from the rat stomach.43 However, in normal-weight humans, the consumption of food for pleasure has been associated with increased ghrelin and 2-AG plasma levels,44 implying a close link between the ECS and the ghrelin system in the regulation of reward-related responses.

As for the exact role of CB1 receptor signaling in the regulation of food intake and energy balance, this varies upon the specific circuits on which the CB1 exerts its function. Recent studies have demonstrated that CB1 receptor activation has opposite effects on food intake depending on whether CB1 receptors are localized on presynaptic terminals of excitatory or inhibitory neurons.45 Thus, although the well-known orexigenic effect of the endocannabinoids seems to depend upon actions at CB1 receptors located at the terminals of cortical glutamatergic neurons, ventral striatal CB1 receptors exert a hypophagic action through the inhibition of GABAergic transmission.45 However, in order to explain the well-known orexigenic effects of CB1 receptor agonists and the anorexigenic effects of CB1 receptor antagonists, one must deduce that CB1 receptor-dependent inhibition of glutamatergic signaling predominates over the action on GABAergic signaling.

Investigations carried out in our laboratory have also demonstrated that virally mediated knockdown of CB1 mRNA expression within the adult mouse hypothalamus causes a lean phenotype by increasing energy expenditure, while not altering basal food intake.34 In other studies, we have shown that basal food intake is not modified in chow-fed mice lacking CB1 in Single-minded homolog 1 (Sim1)-expressing neurons,46 which constitute the majority of neurons of the PVN, or in mice lacking CB1 receptors in SF1-expressing neurons of the ventromedial hypothalamus.35 Interestingly, chow-fed SF1-CB1-knockout (KO) mice are hypophagic when reexposed to food after a prolonged fast,47 but are hyperphagic when fed a high-fat diet.35 Hence, this latest evidence suggests that CB1 receptor signaling in SF1-expressing neurons has opposite effects on feeding behavior that depends upon interaction with other signals (that is, hormones and nutrients) relevant to the regulation of fasting-induced food intake, and upon the type of diet consumed. Indeed, the diet can importantly affect the ECS and its function within the CNS, as endocannabinoids are products of phospholipid-derived arachidonic acid, whose levels can be modified in response to n-3 and n-6 PUFAs present in the diet.48 For instance, lifelong n-3 PUFAs dietary insufficiency abolishes endocannabinoid-dependent long-term synaptic depression, a form of synaptic plasticity, in the NAc and prelimbic prefrontal cortex.49 This is due to the inability of presynaptic CB1 receptors to respond to endocannabinoids because of the uncoupling of their effector Gi/o proteins.49

Altogether, the data reviewed above clearly demonstrate that the ECS regulates feeding behavior by acting upon neuronal circuits located in reward-related structures, the hindbrain and the hypothalamus, and that its activation favors the intake of calories, particularly from palatable food. Recent evidence has further clarified that the net action of endocannabinoids on food intake depends on the neuronal type (that is, glutamatergic vs GABAergic) and that the diet might affect CNS endocannabinoid signaling.

However, the role of ECS in CNS regulation of energy balance might not be limited to the modulation of the activity of CB1 receptors located at the level of the neuronal membrane. CB1 receptors are also present in mouse brain mitochondrial membranes, where they regulate neuronal energy metabolism and endocannabinoid-dependent neurotransmitter release.50, 51 In addition, CB1 receptors are present in astrocytes,52, 53 cells that are being recognized to have important functions in the regulation of energy balance.54 Intriguingly, astroglial CB1 receptors directly interfere with leptin signaling and its ability to regulate glycogen storage, thereby representing a novel mechanism regulating brain energy storage.53 Whether this recently discovered mechanism may affect whole body energy balance is, however, presently unknown.

The ECS and the central and peripheral integration of energy balance

In order to integrate the information coming from the periphery and appropriately coordinate intake, storage and use of calories, the brain must continuously communicate with peripheral organs. Several recently published studies have underscored the ability of CNS endocannabinoid-dependent mechanisms to modulate peripheral processes such as energy expenditure, thermogenesis and lipolysis.34, 35, 46, 55, 56, 57 Mice with selective knockout of CB1 receptors in the forebrain and sympathetic neurons are resistant to diet-induced obesity because they display increased lipid oxidation and thermogenesis as a consequence of enhanced sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity associated with a decrease in energy absorption.56 Virally mediated knockdown of CB1 receptor mRNA in the adult mouse hypothalamus also causes a decrease in body weight gain because of an increase in energy expenditure.34 In addition, deletion of CB1 receptors from Sim1-expressing neurons protects from diet-induced obesity by increasing the expression of thermogenic genes in the brown adipose tissue and by inducing energy expenditure.46 These modifications seem to be due to increased SNS activity, as pharmacological blockade of β-adrenergic receptors or chemical sympathectomy respectively blunt energy expenditure increase and abolish the obesity-resistant phenotype of Sim1-CB1-KO mice.46 Similarly, deletion of CB1 receptors from SF1-expressing neurons protect chow-fed mice from body weight gain by inducing brown adipose tissue thermogenic activity and lipolysis in white adipose tissue (WAT) through heightened SNS activity.35 Accordingly, hypothalamic CB1 signaling is involved in determining the thermogenic effects of MC4R (melanocortin-4 receptor) agonists.58 Genetic models characterized by increased hydrolysis of 2-AG in the forebrain also show increased SNS-mediated brown adipose tissue thermogenesis and mitochondrial density and consequent resistance to diet-induced obesity.59 Thus, the set of recent studies reviewed above has clearly established a link between the ECS in the CNS, the SNS and the regulation of energy balance. Of note, the rapid (within 1 h) hypophagic effect caused by the peripheral administration of rimonabant not only requires peripheral sensory nerve terminals but also depends upon SNS activity.47, 60 In particular, we recently demonstrated that rimonabant-induced hypophagia is fully abolished by peripheral blockade of β-adrenergic transmission.47 The latter also inhibited central effects of CB1 receptor blockade, such as fear responses and anxiety-like behaviors, suggesting that, independently of where they originate from, behavioral effects of CB1 receptor antagonism are expressed via activation of peripheral sympathetic activity.

The ECS and the gastrointestinal tract

When food is introduced into the mouth, it is sensed by the taste buds located on the papillae of the tongue. CB1 receptors are colocalized with type 1 sweet taste receptor 3 on the mouse tongue, and CB1 receptor-dependent endocannabinoid signaling specifically enhances neural responses to sweet taste, as peripheral administration of endocannabinoids increases the neural activity elicited in the chorda tympani by sweeteners, but not by bitter, umami, salty or sour compounds.61 This effect can also be observed in vitro, by applying endocannabinoids directly to taste cells, suggesting that local endocannabinoid signaling in the oral cavity modulates sensitivity to sweet taste.61 Accordingly, AEA, 2-AG and related N-acylethanolamines produced together with endocannabinoids such as oleoylethanolamide and palmitoylethanolamide are quantifiable in human saliva, with their levels being higher in obese patients than normal-weight subjects.62 Although further studies are needed, it is possible that salivary endocannabinoids might play a role in the modulation of orosensory information. In particular, the composition of the meal and the specific presence of fat might affect salivary endocannabinoid and N-acylethanolamines pools that in turn might modulate taste signaling.

Of note, recent studies have demonstrated a link between the ECS and cephalic phase responses elicited in anticipation of a meal to enhance its digestion and metabolism. Cephalic phase responses can be studied in rodents using for instance the sham-feeding model in which the effects of the orosensory properties of the food can be separated from its postingestive qualities. Using this experimental model, it has been shown that gut-derived endocannabinoids regulate the intake of fat based on its orosensory properties.63, 64 Sham-feeding rats with a high-fat liquid meal increases AEA and 2-AG levels specifically in the jejunal part of the small intestine.63, 64 The intestinal increase in endocannabinoids in turn induces food consumption, as local pharmacological blockade of CB1 receptors in the small intestine just before sham-feeding inhibited food intake.63 Transection of the vagus nerve prevents the sham-feeding effect on gastrointestinal endocannabinoids, implying that signals that originate in the oral cavity are transmitted to the brainstem, and then through the vagus to the intestine, where they induce the production of endocannabinoids.3, 63 Certain types of fatty acids may actually be responsible for the cephalic phase of gut endocannabinoid production, as sham-feeding emulsions containing oleic acid or linoleic acid caused a nearly twofold accumulation of jejunal endocannabinoids.64 Besides, mobilization of endocannabinoids in the gut may be essential for fat preference, as suggested by the observation that rats in a two-bottle-choice sham-feeding test displayed strong preference for emulsions containing linoleic acid that was blocked by the administration of a peripherally restricted CB1 receptor antagonist.64 Intriguingly, it has been proposed that a greater intake of food rich in linoleic acid rather than saturated fats might be one of the underlying causes of obesity, as the presence of linoleic acid in western diet has increased over this past century and is positively associated with the increase in obesity in rates.65

Thus, the evidence reviewed above has clearly established that gut-produced endocannabinoids importantly affect fat intake and preference. Recent studies have also revealed that gut microbiota, which is known to influence energy balance and metabolism, controls the gastrointestinal ECS tone.66, 67 The latter can increase gut permeability that, by augmenting lipopolysaccharide levels, further exacerbates the ECS tone in both the gastrointestinal tract and the WAT, favoring body weight gain.67 However, additional investigations are needed in order to better clarify the relationship between gut microbiota and the ECS, particularly as later, apparently contradictory, findings have demonstrated that beneficial gut microbiota, which protects from fat mass gain and insulin resistance, actually increases 2-AG content in the ileum.68

The ECS in other peripheral organs and circulating endocannabinoids

After its initial discovery, the CB1 receptor was known as the brain cannabinoid receptor. This nomenclature had to change in 2003 when groundbreaking work by Cota et al.19 and Bensaid et al.69 demonstrated the functional presence of the CB1 receptor on white adipocytes.

Since then, the role of peripheral CB1 in adipocytes as well as in hepatocytes, pancreas and skeletal muscle has been deeply investigated and better characterized, opening new perspectives for the treatment of metabolic disorders.

CB1 receptor activation in white adipocytes increases the expression of genes associated with adipocyte differentiation, such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), and impairs mitochondrial biogenesis.70, 71 Conversely, pharmacological blockade or genetic deletion of CB1 receptors stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis through the increased expression of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase,72 and induces the transdifferentiation of white adipocytes into a thermogenic brown fat phenotype characterized by increased UCP-1 (uncoupling protein-1) and PGC-1α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α) expression and enhanced AMP-activated protein kinase activity.73 Similarly, CB1 receptor blockade activates brown adipocytes, resulting in enhanced uncoupled respiration.74

White adipocyte CB1 receptor activation causes increased fatty acid synthesis and triglycerides accumulation, whereas the opposite is observed when pharmacologically blocking or genetically deleting this receptor.19, 69, 75 Moreover, endocannabinoid production in white adipocytes is negatively regulated by insulin and leptin.75, 76 Consequently, conditions characterized by leptin and insulin resistance, such as diet-induced obesity, might favor ECS overactivity in the WAT that in turn might further support fat accumulation and body weight gain. However, controversy exists on whether the above described changes in adipocyte function, which are due to the modulation of adipocyte CB1 receptor activity in vitro, are relevant in vivo, particularly if one considers studies that have demonstrated that the ECS regulates WAT lipogenesis/lipolysis through the SNS and not at tissue level.77 Nevertheless, findings obtained using adipocyte-specific CB1-KO mice do suggest that adipocyte CB1 receptors favor WAT expansion and the development of obesity in vivo.78

Similar to white adipocytes, activation of CB1 receptors in hepatocytes causes lipid accumulation and leads to liver steatosis by inducing the expression of lipogenic enzymes, such as ACC1 (acetyl coenzyme-A carboxylase-1) and fatty acid synthase, and by increasing de novo fatty acid synthesis.79 Mice with specific deletion of CB1 receptors in hepatocytes, although still gaining body weight when consuming a high-fat diet, do not develop liver steatosis, hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia and insulin resistance.80 Similarly, the beneficial effects of a peripherally restricted CB1 receptor antagonist on liver steatosis and insulin resistance depend upon the action of the compound on hepatocyte CB1 receptors.81, 82 Thus, these recent findings imply that endocannabinoid-dependent CB1 receptor signaling in hepatocytes may have a particularly relevant role in the regulation of lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity.

At the molecular level, activation of hepatic CB1 receptors favors insulin resistance through the upregulation of the inhibitory phosphorylation of the insulin receptor substrate and of the inhibitory dephosphorylation of the insulin-activated protein kinase B with consequent recruitment of an endoplasmic reticulum stress-dependent pathway.83 A number of studies have also implicated both CB1 and CB2 receptors in the regulation of fibrogenic responses in the liver and the reader should refer to recent reviews that have specifically addressed the role of the ECS in liver physiopathology.84

Both CB1 and CB2 receptors are present in rodent and human pancreatic islets and show species-dependent degree of expression, with CB1 receptor signaling regulating both insulin signaling and insulin release.85 A series of recent investigations has in particular detailed the role of CB1 in the β-cell. Activation of CB1 receptors in β-cells has been shown to recruit focal adhesion kinases that lead to exocytosis of secretory insulin vesicles through cytoskeletal reorganization.86 Conversely, pharmacological CB1 receptor blockade inhibits insulin secretion in vitro only when elevated above normal, as it can be found in diet-induced obesity, indicating that under this condition there is a higher endocannabinoid tone in the endocrine pancreas, similar to what is described in other organs. CB1 receptor blockade also ameliorates β-cell function in obesity by increasing β-cell proliferation and mass.87 Conversely, CB1 receptor activation induces apoptotic activity and β-cell death.88 Actually, it has been recently demonstrated that macrophage infiltration of pancreatic islets and consequent inflammation, which plays a pathogenic role in diabetes, is under the control of CB1 receptor activity and leads to β-cell loss in type 2 diabetes.89 Accordingly, peripheral CB1 receptor blockade, in vivo depletion of macrophages or macrophage-specific knockdown of the CB1 receptor restores normoglycemia and glucose-induced insulin secretion.89 Therefore, these latest findings imply that pharmacological interventions aimed at inhibiting peripheral CB1 receptors might represent new attractive avenues for the treatment of diabetes, independently of their possible beneficial effects on body weight, lipid metabolism and insulin resistance.

Endocannabinoids and the different ECS components are also present in the skeletal muscle. Muscle endocannabinoids and muscle CB1 receptor expression are altered by high-fat diet consumption and in animal models of obesity,; although changes (increase or decrease) might depend on the specific muscle or genetic model studied (reviewed in Silvestri and Di Marzo4). Some data imply that overactivity of the ECS in the skeletal muscle might drive defective oxidative metabolism, as activation of the ECS in muscle inhibits oxidative pathways and mitochondrial biogenesis.71 Moreover, CB1 receptor activation in isolated soleus muscle from either lean or obese animals hampers both basal and insulin-stimulated glucose transport, whereas pharmacological blockade of CB1 improves glucose transport.4 In particular, activation of muscle CB1 receptor negatively affects the responsiveness of the tissue to insulin through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B and the Raf-MEK1/2-ERK1/2 intracellular pathways, among other molecular cascades (reviewed in Silvestri and Di Marzo4), suggesting that CB1-driven changes in muscle might favor insulin resistance.

Finally, endocannabinoids can be detected in the circulation, and measurement of endocannabinoids in the plasma or serum has been a favorite approach for the study of the ECS in humans (see also Table 1). Plasma endocannabinoid levels correlate positively with markers of obesity and metabolic disorder in humans, such as the body mass index, the waist circumference, visceral fat mass and insulin resistance.90, 91, 92, 93 It has actually been recently suggested that circulating endocannabinoids might work as biomarkers of WAT distribution and insulin resistance.4 Consequently, they might be used not only as markers of specific phenotypes, but also to predict responsiveness to treatment. However, several issues for the clinical use of circulating endocannabinoids still remain unresolved, including the requirement for standardized methods dealing with the extraction and the measurement of endocannabinoids and the establishment of reference levels for plasma/serum endocannabinoids in humans that might be affected by age and gender, among other factors.94 Other points that currently require further investigation include the possible participation of circulating endocannabinoids in signaling events that might affect feeding and metabolism, and the actual origin(s) of circulating endocannabinoids. Circulating levels of endocannabinoids change in healthy and obese humans in relation to food intake.93, 95 In particular, we have demonstrated that both normal-weight and obese subjects have a significant preprandial AEA peak, a finding implying that AEA might work as a physiological meal initiator.93 Differently from AEA, no meal-related changes were found for 2-AG, suggesting that 2-AG might not work as a hunger signal in humans.93 As to from where the observed changes in AEA and 2-AG plasma levels originate, we have proposed as a probable candidate the gastrointestinal tract,93 as it produces endocannabinoids in relation to food intake.63

The ECS as a target for the treatment of obesity and metabolic disorders

Evidence reviewed above pinpoints the CB1 receptor as the best characterized potential pharmacological target through which the ECS can be modulated in obesity and metabolic disorders. This has been due in great part to the fact that rimonabant, the first systemically penetrant CB1 receptor inverse agonist, was developed soon after the discovery of the CB1 receptor.96 Chronic administration of rimonabant in obese rodents and humans reliably decreases body weight and fat mass, improves glucose homeostasis and ameliorates insulin sensitivity and associated cardiometabolic risks.97 However, the neuropsychiatric side effects, which were more common than what were initially estimated from the clinical trials, and the overall benefits being lower than the risks, led to the withdrawal of rimonabant from the market and to the dismissal of similar CB1 receptor antagonists. Yet, as the ECS is strategically positioned to regulate every step affecting the intake, storage and use of calories, research over the past 5 years has intensely and successfully pursued the development of novel approaches to modulate ECS activity. These strategies, summarized in Table 2, are based on very different and equally attractive approaches either targeting CB1 with peripherally restricted antagonists or allosteric inhibitors or neutral antagonists or directly targeting the endogenous ligands through the diet or inhibitors of endocannabinoid synthesis. In particular, Tam et al.81, 82 were the first to characterize the metabolic effects of AM6545, a peripherally restricted CB1 receptor neutral antagonist, that does not alter behavioral responses mediated by CNS CB1 receptors, while reversing leptin resistance and inducing weight-independent improvements in glucose homeostasis, liver steatosis and plasma lipid profiles in genetic or diet-induced obese mice. However, very recent findings have suggested that endogenous compounds, such as hemopressin or the neurosteroid pregnenolone, that are able to act as allosteric inhibitors of CB1 might avoid causing side effects because of modulating CB1 receptor activity in a signaling-specific way and/or by engaging distinct neuronal substrates within the CNS.98, 99, 100, 101, 102 Thus, pharmacological compounds mimicking the actions of endogenous allosteric inhibitors might represent a novel, efficacious way to modulate ECS activity in pathology. Although targeting CB1 receptors for the treatment of obesity and metabolic disorders remains the option with most descriptive and mechanistic information available, alternative possibilities exist. For instance, recent studies suggest a metabolic role for CB2 receptors that might be an interesting target for the treatment of at least some metabolic disorders, particularly considering the function of this receptor in the regulation of immune and inflammatory responses.4, 84 Additional therapeutic potential targets are also non-cannabinoid receptors that can be activated by endocannabinoids, such as the TRPV1 (transient receptor potential vanilloid 1) and the PPARs. However, further work is required in order to better understand the role of these receptors in the context of endocannabinoid-dependent regulation of energy balance and metabolism.

As obesity is characterized by upregulation of the endocannabinoid tone, which can be in part attributed to increased endocannabinoid synthesis, other therapeutic possibilities are given by compounds that can interfere with endocannabinoid synthesis or that increase endocannabinoid degradation. For instance, diacylglicerol lipase inhibitors, which decrease 2-AG synthesis, inhibit food intake and body weight in mice.103 Another therapeutic possibility is the decrease in the availability of endocannabinoid precursors. This could be attained by increasing the levels of dietary n-3 PUFAs. In fact, it has been demonstrated that the increased intake of dietary n-3 PUFAs in obese rats reduces endocannabinoid levels in adipose tissue, liver and heart, limiting ectopic fat accumulation and inflammatory responses.104 Similarly, hypercholesterolemic patients consuming sheep cheese enriched in n-3 PUFAs for 3 weeks have decreased plasma AEA levels and improved lipid profile.105 Thus, increasing the dietary consumption of n-3 PUFAs might regulate endocannabinoid levels so to help in preventing or treating metabolic disorders. Finally, considering the complexity and redundancy of the mechanisms regulating energy balance, the ECS could be targeted in association with other biological systems.106, 107 This strategy is an extremely attractive approach for the treatment of obesity that, by preferring the combination of low doses of compounds targeting different systems or different components of the same system, helps limiting the appearance of unwanted side effects.

Concluding remarks: the challenges ahead

Research over the past 5 years has significantly expanded our knowledge about the ECS and its role in the regulation of energy balance. In particular, new evidence has shown an involvement of the ECS in the modulation of taste and olfaction and the role of this system at the level of the gastrointestinal tract in the regulation of fat intake and preference. Other studies have proven the function of the CNS ECS in the regulation of peripheral metabolism, and further knowledge has been provided on the actions of the peripheral ECS and its impact particularly on glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity. The main conclusion is that the ECS generally acts to preserve and stock energy in the body. Thus, although activation of this system is beneficial in conditions in which the availability of food is limited or cannot be predicted, it favors the development of obesity and metabolic syndrome when palatable, calorically rich food becomes easily available.

Here we have mainly focused on the functions of AEA, 2-AG and CB1 receptors, as a great part of the information concerning the role of the ECS in energy balance is related to these endocannabinoids and to this specific cannabinoid receptor. However, we need to mention that endocannabinoids can affect metabolic responses by acting on receptors (that is, PPARs or TRPV1) other than cannabinoid receptors. In addition, endocannabinoids are synthetized together with other bioactive lipids that, while sharing structural similarities with the endocannabinoids, do not bind to cannabinoid receptors. Among those, oleoylethanolamide, a lipid related to AEA, decreases appetite and favors weight loss and lipolysis by acting through PPARα, contrasting the metabolic effects of endocannabinoid-dependent CB1 receptor activation.108 Thus, the information generated so far on the ability of endocannabinoids to bind to receptors other than cannabinoid receptors, the redundancy of their metabolic pathways, the presence of endocannabinoid-related compounds that oppose the actions of endocannabinoids and the identification of endogenous modulators of CB1 receptor activity represent a complicated scenario that asks for substantial additional investigation in order to fully grasp the impact of the ECS in energy balance and metabolism. Apart from these challenges, available evidence suggests that the ECS remains an attractive target for therapy. Thus, there is strong hope that new therapeutic approaches targeting the ECS might successfully help tackling obesity and metabolic disorders.

References

Quarta C, Mazza R, Obici S, Pasquali R, Pagotto U . Energy balance regulation by endocannabinoids at central and peripheral levels. Trends Mol Med 2011; 17: 518–526.

Bermudez-Silva FJ, Cardinal P, Cota D . The role of the endocannabinoid system in the neuroendocrine regulation of energy balance. J Psychopharmacol 2012; 26: 114–124.

DiPatrizio NV, Piomelli D . The thrifty lipids: endocannabinoids and the neural control of energy conservation. Trends Neurosci 2012; 35: 403–411.

Silvestri C, Di Marzo V . The endocannabinoid system in energy homeostasis and the etiopathology of metabolic disorders. Cell Metab 2013; 17: 475–490.

Di Marzo V . The endocannabinoid system: its general strategy of action, tools for its pharmacological manipulation and potential therapeutic exploitation. Pharmacol Res 2009; 60: 77–84.

Katona I, Freund TF . Endocannabinoid signaling as a synaptic circuit breaker in neurological disease. Nat Med 2008; 14: 923–930.

Pertwee RG, Howlett AC, Abood ME, Alexander SP, Di Marzo V, Elphick MR et al. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIX. Cannabinoid receptors and their ligands: beyond CB1 and CB2. Pharmacol Rev 2010; 62: 588–631.

Pagotto U, Marsicano G, Cota D, Lutz B, Pasquali R . The emerging role of the endocannabinoid system in endocrine regulation and energy balance. Endocr Rev 2006; 27: 73–100.

Silvestri C, Di Marzo V . Second generation CB1 receptor blockers and other inhibitors of peripheral endocannabinoid overactivity and the rationale of their use against metabolic disorders. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2012; 21: 1309–1322.

Wilson RI, Nicoll RA . Endogenous cannabinoids mediate retrograde signalling at hippocampal synapses. Nature 2001; 410: 588–592.

Colombo G, Agabio R, Diaz G, Lobina C, Reali R, Gessa GL . Appetite suppression and weight loss after the cannabinoid antagonist SR 141716. Life Sci 1998; 63: PL113–PL117.

Simiand J, Keane M, Keane PE, Soubrie P . SR 141716, a CB1 cannabinoid receptor antagonist, selectively reduces sweet food intake in marmoset. Behav Pharmacol 1998; 9: 179–181.

Williams CM, Kirkham TC . Anandamide induces overeating: mediation by central cannabinoid (CB1) receptors. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999; 143: 315–317.

Cota D, Genghini S, Pasquali R, Pagotto U . Antagonizing the cannabinoid receptor type 1: a dual way to fight obesity. J Endocrinol Invest 2003; 26: 1041–1044.

Despres JP, Golay A, Sjostrom L . Effects of rimonabant on metabolic risk factors in overweight patients with dyslipidemia. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 2121–2134.

Di Marzo V, Despres JP . CB1 antagonists for obesity—what lessons have we learned from rimonabant? Nat Rev Endocrinol 2009; 5: 633–638.

Pi-Sunyer FX, Aronne LJ, Heshmati HM, Devin J, Rosenstock J . Effect of rimonabant, a cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker, on weight and cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight or obese patients: RIO-North America: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006; 295: 761–775.

Van Gaal LF, Rissanen AM, Scheen AJ, Ziegler O, Rossner S . Effects of the cannabinoid-1 receptor blocker rimonabant on weight reduction and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight patients: 1-year experience from the RIO-Europe study. Lancet 2005; 365: 1389–1397.

Cota D, Marsicano G, Tschop M, Grubler Y, Flachskamm C, Schubert M et al. The endogenous cannabinoid system affects energy balance via central orexigenic drive and peripheral lipogenesis. J Clin Invest 2003; 112: 423–431.

Ravinet Trillou C, Delgorge C, Menet C, Arnone M, Soubrie P . CB1 cannabinoid receptor knockout in mice leads to leanness, resistance to diet-induced obesity and enhanced leptin sensitivity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2004; 28: 640–648.

Morton GJ, Cummings DE, Baskin DG, Barsh GS, Schwartz MW . Central nervous system control of food intake and body weight. Nature 2006; 443: 289–295.

Berridge KC, Ho CY, Richard JM, DiFeliceantonio AG . The tempted brain eats: pleasure and desire circuits in obesity and eating disorders. Brain Res 2010; 1350: 43–64.

Grill HJ, Hayes MR . Hindbrain neurons as an essential hub in the neuroanatomically distributed control of energy balance. Cell Metab 2012; 16: 296–309.

Jamshidi N, Taylor DA . Anandamide administration into the ventromedial hypothalamus stimulates appetite in rats. Br J Pharmacol 2001; 134: 1151–1154.

Kirkham TC, Williams CM, Fezza F, Di Marzo V . Endocannabinoid levels in rat limbic forebrain and hypothalamus in relation to fasting, feeding and satiation: stimulation of eating by 2-arachidonoyl glycerol. Br J Pharmacol 2002; 136: 550–557.

Mahler SV, Smith KS, Berridge KC . Endocannabinoid hedonic hotspot for sensory pleasure: anandamide in nucleus accumbens shell enhances 'liking' of a sweet reward. Neuropsychopharmacology 2007; 32: 2267–2278.

De Luca MA, Solinas M, Bimpisidis Z, Goldberg SR, Di Chiara G . Cannabinoid facilitation of behavioral and biochemical hedonic taste responses. Neuropharmacology 2012; 63: 161–168.

Melis T, Succu S, Sanna F, Boi A, Argiolas A, Melis MR . The cannabinoid antagonist SR 141716A (Rimonabant) reduces the increase of extra-cellular dopamine release in the rat nucleus accumbens induced by a novel high palatable food. Neurosci Lett 2007; 419: 231–235.

Maldonado R, Valverde O, Berrendero F . Involvement of the endocannabinoid system in drug addiction. Trends Neurosci 2006; 29: 225–232.

DiPatrizio NV, Simansky KJ . Activating parabrachial cannabinoid CB1 receptors selectively stimulates feeding of palatable foods in rats. J Neurosci 2008; 28: 9702–9709.

Soria-Gomez E, Bellocchio L, Reguero L, Lepousez G, Martin C, Bendahmane M et al. The endocannabinoid system controls food intake via olfactory processes. Nat Neurosci 2014; 17: 407–415.

Di Marzo V, Goparaju SK, Wang L, Liu J, Batkai S, Jarai Z et al. Leptin-regulated endocannabinoids are involved in maintaining food intake. Nature 2001; 410: 822–825.

Jo YH, Chen YJ, Chua SC Jr, Talmage DA, Role LW . Integration of endocannabinoid and leptin signaling in an appetite-related neural circuit. Neuron 2005; 48: 1055–1066.

Cardinal P, Bellocchio L, Clark S, Cannich A, Klugmann M, Lutz B et al. Hypothalamic CB1 cannabinoid receptors regulate energy balance in mice. Endocrinology 2012; 153: 4136–4143.

Cardinal P, Andre C, Quarta C, Bellocchio L, Clark S, Elie M et al. CB1 cannabinoid receptor in SF1-expressing neurons of the ventromedial hypothalamus determines metabolic responses to diet and leptin. Mol Metab 2014; 3: 705–716.

Cristino L, Busetto G, Imperatore R, Ferrandino I, Palomba L, Silvestri C et al. Obesity-driven synaptic remodeling affects endocannabinoid control of orexinergic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: E2229–E2238.

Di S, Malcher-Lopes R, Halmos KC, Tasker JG . Nongenomic glucocorticoid inhibition via endocannabinoid release in the hypothalamus: a fast feedback mechanism. J Neurosci 2003; 23: 4850–4857.

Malcher-Lopes R, Di S, Marcheselli VS, Weng FJ, Stuart CT, Bazan NG et al. Opposing crosstalk between leptin and glucocorticoids rapidly modulates synaptic excitation via endocannabinoid release. J Neurosci 2006; 26: 6643–6650.

O'Hare JD, Zielinski E, Cheng B, Scherer T, Buettner C . Central endocannabinoid signaling regulates hepatic glucose production and systemic lipolysis. Diabetes 2011; 60: 1055–1062.

Tucci SA, Rogers EK, Korbonits M, Kirkham TC . The cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716 blocks the orexigenic effects of intrahypothalamic ghrelin. Br J Pharmacol 2004; 143: 520–523.

Hardie DG, Ross FA, Hawley SA . AMPK: a nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2012; 13: 251–262.

Kola B, Farkas I, Christ-Crain M, Wittmann G, Lolli F, Amin F et al. The orexigenic effect of ghrelin is mediated through central activation of the endogenous cannabinoid system. PLoS One 2008; 3: e1797.

Zbucki RL, Sawicki B, Hryniewicz A, Winnicka MM . Cannabinoids enhance gastric X/A-like cells activity. Folia Histochem Cytobiol 2008; 46: 219–224.

Monteleone P, Piscitelli F, Scognamiglio P, Monteleone AM, Canestrelli B, Di Marzo V et al. Hedonic eating is associated with increased peripheral levels of ghrelin and the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoyl-glycerol in healthy humans: a pilot study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97: E917–E924.

Bellocchio L, Lafenetre P, Cannich A, Cota D, Puente N, Grandes P et al. Bimodal control of stimulated food intake by the endocannabinoid system. Nat Neurosci 2010; 13: 281–283.

Cardinal P, Bellocchio L, Guzman-Quevedo O, Andre C, Clark S, Elie M et al. Cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) receptors on Sim1-expressing neurons regulate energy expenditure in male mice. Endocrinology 2015; 156: 411–418.

Bellocchio L, Soria-Gomez E, Quarta C, Metna-Laurent M, Cardinal P, Binder E et al. Activation of the sympathetic nervous system mediates hypophagic and anxiety-like effects of CB(1) receptor blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 4786–4791.

Di Marzo V . Endocannabinoids: synthesis and degradation. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 2008; 160: 1–24.

Lafourcade M, Larrieu T, Mato S, Duffaud A, Sepers M, Matias I et al. Nutritional omega-3 deficiency abolishes endocannabinoid-mediated neuronal functions. Nat Neurosci 2011; 14: 345–350.

Benard G, Massa F, Puente N, Lourenco J, Bellocchio L, Soria-Gomez E et al. Mitochondrial CB(1) receptors regulate neuronal energy metabolism. Nat Neurosci 2012; 15: 558–564.

Hebert-Chatelain E, Reguero L, Puente N, Lutz B, Chaouloff F, Rossignol R et al. Cannabinoid control of brain bioenergetics: exploring the subcellular localization of the CB1 receptor. Mol Metab 2014; 3: 495–504.

Han J, Kesner P, Metna-Laurent M, Duan T, Xu L, Georges F et al. Acute cannabinoids impair working memory through astroglial CB1 receptor modulation of hippocampal LTD. Cell 2012; 148: 1039–1050.

Bosier B, Bellocchio L, Metna-Laurent M, Soria-Gomez E, Matias I, Hebert-Chatelain E et al. Astroglial CB1 cannabinoid receptors regulate leptin signaling in mouse brain astrocytes. Mol Metab 2013; 2: 393–404.

Garcia-Caceres C, Fuente-Martin E, Argente J, Chowen JA . Emerging role of glial cells in the control of body weight. Mol Metab 2012; 1: 37–46.

Bajzer M, Olivieri M, Haas MK, Pfluger PT, Magrisso IJ, Foster MT et al. Cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) antagonism enhances glucose utilisation and activates brown adipose tissue in diet-induced obese mice. Diabetologia 2011; 54: 3121–3131.

Quarta C, Bellocchio L, Mancini G, Mazza R, Cervino C, Braulke LJ et al. CB(1) signaling in forebrain and sympathetic neurons is a key determinant of endocannabinoid actions on energy balance. Cell Metab 2010; 11: 273–285.

Verty AN, Allen AM, Oldfield BJ . The effects of rimonabant on brown adipose tissue in rat: implications for energy expenditure. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009; 17: 254–261.

Monge-Roffarello B, Labbe SM, Roy MC, Lemay ML, Coneggo E, Samson P et al. The PVH as a site of CB1-mediated stimulation of thermogenesis by MC4R agonism in male rats. Endocrinology 2014; 155: 3448–3458.

Jung KM, Clapper JR, Fu J, D'Agostino G, Guijarro A, Thongkham D et al. 2-arachidonoylglycerol signaling in forebrain regulates systemic energy metabolism. Cell Metab 2012; 15: 299–310.

Gomez R, Navarro M, Ferrer B, Trigo JM, Bilbao A, Del Arco I et al. A peripheral mechanism for CB1 cannabinoid receptor-dependent modulation of feeding. J Neurosci 2002; 22: 9612–9617.

Yoshida R, Ohkuri T, Jyotaki M, Yasuo T, Horio N, Yasumatsu K et al. Endocannabinoids selectively enhance sweet taste. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 935–939.

Matias I, Gatta-Cherifi B, Tabarin A, Clark S, Leste-Lasserre T, Marsicano G et al. Endocannabinoids measurement in human saliva as potential biomarker of obesity. PLoS One 2012; 7: e42399.

DiPatrizio NV, Astarita G, Schwartz G, Li X, Piomelli D . Endocannabinoid signal in the gut controls dietary fat intake. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2011; 108: 12904–12908.

DiPatrizio NV, Joslin A, Jung KM, Piomelli D . Endocannabinoid signaling in the gut mediates preference for dietary unsaturated fats. FASEB J 2013; 27: 2513–2520.

DiPatrizio NV . Is fat taste ready for primetime? Physiol Behav 2014; 136: 145–154.

Cani PD . Metabolism in 2013: the gut microbiota manages host metabolism. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2014; 10: 74–76.

Muccioli GG, Naslain D, Backhed F, Reigstad CS, Lambert DM, Delzenne NM et al. The endocannabinoid system links gut microbiota to adipogenesis. Mol Syst Biol 2010; 6: 392.

Everard A, Belzer C, Geurts L, Ouwerkerk JP, Druart C, Bindels LB et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 9066–9071.

Bensaid M, Gary-Bobo M, Esclangon A, Maffrand JP, Le Fur G, Oury-Donat F et al. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist SR141716 increases Acrp30 mRNA expression in adipose tissue of obese fa/fa rats and in cultured adipocyte cells. Mol Pharmacol 2003; 63: 908–914.

Bouaboula M, Hilairet S, Marchand J, Fajas L, Le Fur G, Casellas P . Anandamide induced PPARgamma transcriptional activation and 3T3-L1 preadipocyte differentiation. Eur J Pharmacol 2005; 517: 174–181.

Tedesco L, Valerio A, Dossena M, Cardile A, Ragni M, Pagano C et al. Cannabinoid receptor stimulation impairs mitochondrial biogenesis in mouse white adipose tissue, muscle, and liver: the role of eNOS, p38 MAPK, and AMPK pathways. Diabetes 2010; 59: 2826–2836.

Tedesco L, Valerio A, Cervino C, Cardile A, Pagano C, Vettor R et al. Cannabinoid type 1 receptor blockade promotes mitochondrial biogenesis through endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression in white adipocytes. Diabetes 2008; 57: 2028–2036.

Perwitz N, Wenzel J, Wagner I, Buning J, Drenckhan M, Zarse K et al. Cannabinoid type 1 receptor blockade induces transdifferentiation towards a brown fat phenotype in white adipocytes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2010; 12: 158–166.

Boon MR, Kooijman S, van Dam AD, Pelgrom LR, Berbee JF, Visseren CA et al. Peripheral cannabinoid 1 receptor blockade activates brown adipose tissue and diminishes dyslipidemia and obesity. FASEB J 2014; 28: 5361–5375.

Matias I, Gonthier MP, Orlando P, Martiadis V, De Petrocellis L, Cervino C et al. Regulation, function, and dysregulation of endocannabinoids in models of adipose and beta-pancreatic cells and in obesity and hyperglycemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006; 91: 3171–3180.

D'Eon TM, Pierce KA, Roix JJ, Tyler A, Chen H, Teixeira SR . The role of adipocyte insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of obesity-related elevations in endocannabinoids. Diabetes 2008; 57: 1262–1268.

Molhoj S, Hansen HS, Schweiger M, Zimmermann R, Johansen T, Malmlof K . Effect of the cannabinoid receptor-1 antagonist rimonabant on lipolysis in rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2010; 646: 38–45.

Mancini G, Quarta C, Srivastava RK, Klaus S, Pagotto U, Lutz B . Adipocye-specific CB1 conditional knock-out mice: new insights in the study of obesity and metabolic syndrome. Paper presented at the 20th Annual Symposium of the International Cannabinoid Society 23–27 July 2010 Lund, Sweden International Cannabinoid Research Society: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2010.

Osei-Hyiaman D, DePetrillo M, Pacher P, Liu J, Radaeva S, Batkai S et al. Endocannabinoid activation at hepatic CB1 receptors stimulates fatty acid synthesis and contributes to diet-induced obesity. J Clin Invest 2005; 115: 1298–1305.

Osei-Hyiaman D, Liu J, Zhou L, Godlewski G, Harvey-White J, Jeong WI et al. Hepatic CB1 receptor is required for development of diet-induced steatosis, dyslipidemia, and insulin and leptin resistance in mice. J Clin Invest 2008; 118: 3160–3169.

Tam J, Vemuri VK, Liu J, Batkai S, Mukhopadhyay B, Godlewski G et al. Peripheral CB1 cannabinoid receptor blockade improves cardiometabolic risk in mouse models of obesity. J Clin Invest 2010; 120: 2953–2966.

Tam J, Cinar R, Liu J, Godlewski G, Wesley D, Jourdan T et al. Peripheral cannabinoid-1 receptor inverse agonism reduces obesity by reversing leptin resistance. Cell Metab 2012; 16: 167–179.

Liu J, Zhou L, Xiong K, Godlewski G, Mukhopadhyay B, Tam J et al. Hepatic cannabinoid receptor-1 mediates diet-induced insulin resistance via inhibition of insulin signaling and clearance in mice. Gastroenterology 2012; 142: 1218–1228 e1211.

Mallat A, Teixeira-Clerc F, Lotersztajn S . Cannabinoid signaling and liver therapeutics. J Hepatol 2013; 59: 891–896.

Li C, Jones PM, Persaud SJ . Role of the endocannabinoid system in food intake, energy homeostasis and regulation of the endocrine pancreas. Pharmacol Ther 2011; 129: 307–320.

Malenczyk K, Jazurek M, Keimpema E, Silvestri C, Janikiewicz J, Mackie K et al. CB1 cannabinoid receptors couple to focal adhesion kinase to control insulin release. J Biol Chem 2013; 288: 32685–32699.

Kim W, Doyle ME, Liu Z, Lao Q, Shin YK, Carlson OD et al. Cannabinoids inhibit insulin receptor signaling in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes 2011; 60: 1198–1209.

Kim W, Lao Q, Shin YK, Carlson OD, Lee EK, Gorospe M et al. Cannabinoids induce pancreatic beta-cell death by directly inhibiting insulin receptor activation. Sci Signal 2012; 5: ra23.

Jourdan T, Godlewski G, Cinar R, Bertola A, Szanda G, Liu J et al. Activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome in infiltrating macrophages by endocannabinoids mediates beta cell loss in type 2 diabetes. Nat Med 2013; 19: 1132–1140.

Engeli S, Bohnke J, Feldpausch M, Gorzelniak K, Janke J, Batkai S et al. Activation of the peripheral endocannabinoid system in human obesity. Diabetes 2005; 54: 2838–2843.

Bluher M, Engeli S, Kloting N, Berndt J, Fasshauer M, Batkai S et al. Dysregulation of the peripheral and adipose tissue endocannabinoid system in human abdominal obesity. Diabetes 2006; 55: 3053–3060.

Cote M, Matias I, Lemieux I, Petrosino S, Almeras N, Despres JP et al. Circulating endocannabinoid levels, abdominal adiposity and related cardiometabolic risk factors in obese men. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007; 31: 692–699.

Gatta-Cherifi B, Matias I, Vallee M, Tabarin A, Marsicano G, Piazza PV et al. Simultaneous postprandial deregulation of the orexigenic endocannabinoid anandamide and the anorexigenic peptide YY in obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012; 36: 880–885.

Fanelli F, Di Lallo VD, Belluomo I, De Iasio R, Baccini M, Casadio E et al. Estimation of reference intervals of five endocannabinoids and endocannabinoid related compounds in human plasma by two dimensional-LC/MS/MS. J Lipid Res 2011; 53: 481–493.

Matias I, Gonthier MP, Petrosino S, Docimo L, Capasso R, Hoareau L et al. Role and regulation of acylethanolamides in energy balance: focus on adipocytes and beta-cells. Br J Pharmacol 2007; 152: 676–690.

Rinaldi-Carmona M, Barth F, Heaulme M, Shire D, Calandra B, Congy C et al. SR141716A, a potent and selective antagonist of the brain cannabinoid receptor. FEBS Lett 1994; 350: 240–244.

Cota D . CB1 receptors: emerging evidence for central and peripheral mechanisms that regulate energy balance, metabolism, and cardiovascular health. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2007; 23: 507–517.

Dodd GT, Mancini G, Lutz B, Luckman SM . The peptide hemopressin acts through CB1 cannabinoid receptors to reduce food intake in rats and mice. J Neurosci 2010; 30: 7369–7376.

Piazza PV, Vallée M, Marsicano G, Felpin FX, Bellocchio L, Cota D et al Antagonists of CB1 receptor. Patent Publication No. WO/2012/160006. International Application No.: PCT/EP2012/059310 2012.

Dodd GT, Worth AA, Hodkinson DJ, Srivastava RK, Lutz B, Williams SR et al. Central functional response to the novel peptide cannabinoid, hemopressin. Neuropharmacology 2013; 71: 27–36.

Bauer M, Chicca A, Tamborrini M, Eisen D, Lerner R, Lutz B et al. Identification and quantification of a new family of peptide endocannabinoids (Pepcans) showing negative allosteric modulation at CB1 receptors. J Biol Chem 2012; 287: 36944–36967.

Vallee M, Vitiello S, Bellocchio L, Hebert-Chatelain E, Monlezun S, Martin-Garcia E et al. Pregnenolone can protect the brain from cannabis intoxication. Science 2014; 343: 94–98.

Bisogno T, Mahadevan A, Coccurello R, Chang JW, Allara M, Chen Y et al. A novel fluorophosphonate inhibitor of the biosynthesis of the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol with potential anti-obesity effects. Br J Pharmacol 2013; 169: 784–793.

Batetta B, Griinari M, Carta G, Murru E, Ligresti A, Cordeddu L et al. Endocannabinoids may mediate the ability of (n-3) fatty acids to reduce ectopic fat and inflammatory mediators in obese Zucker rats. J Nutr 2009; 139: 1495–1501.

Pintus S, Murru E, Carta G, Cordeddu L, Batetta B, Accossu S et al. Sheep cheese naturally enriched in alpha-linolenic, conjugated linoleic and vaccenic acids improves the lipid profile and reduces anandamide in the plasma of hypercholesterolaemic subjects. Br J Nutr 2013; 109: 1453–1462.

Verty AN, Lockie SH, Stefanidis A, Oldfield BJ . Anti-obesity effects of the combined administration of CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant and melanin-concentrating hormone antagonist SNAP-94847 in diet-induced obese mice. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013; 37: 279–287.

White NE, Dhillo WS, Liu YL, Small CJ, Kennett GA, Gardiner JV et al. Co-administration of SR141716 with peptide YY3-36 or oxyntomodulin has additive effects on food intake in mice. Diabetes Obes Metab 2008; 10: 167–170.

Piomelli D . A fatty gut feeling. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2013; 24: 332–341.

Di Marzo V, Verrijken A, Hakkarainen A, Petrosino S, Mertens I, Lundbom N et al. Role of insulin as a negative regulator of plasma endocannabinoid levels in obese and nonobese subjects. Eur J Endocrinol 2009; 161: 715–722.

Sipe JC, Scott TM, Murray S, Harismendy O, Simon GM, Cravatt BF et al. Biomarkers of endocannabinoid system activation in severe obesity. PLoS One 2010; 5: e8792.

Jumpertz R, Guijarro A, Pratley RE, Piomelli D, Krakoff J . Central and peripheral endocannabinoids and cognate acylethanolamides in humans: association with race, adiposity, and energy expenditure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96: 115–121.

Monteleone P, Matias I, Martiadis V, De Petrocellis L, Maj M, Di Marzo V . Blood levels of the endocannabinoid anandamide are increased in anorexia nervosa and in binge-eating disorder, but not in bulimia nervosa. Neuropsychopharmacology 2005; 30: 1216–1221.

Jumpertz R, Wiesner T, Bluher M, Engeli S, Batkai S, Wirtz H et al. Circulating endocannabinoids and N-acyl-ethanolamides in patients with sleep apnea—specific role of oleoylethanolamide. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2010; 118: 591–595.

Engeli S, Bluher M, Jumpertz R, Wiesner T, Wirtz H, Bosse-Henck A et al. Circulating anandamide and blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Hypertens 2012; 30: 2345–2351.

Quercioli A, Pataky Z, Vincenti G, Makoundou V, Di Marzo V, Montecucco F et al. Elevated endocannabinoid plasma levels are associated with coronary circulatory dysfunction in obesity. Eur Heart J 2011; 32: 1369–1378.

Piscitelli F, Carta G, Bisogno T, Murru E, Cordeddu L, Berge K et al. Effect of dietary krill oil supplementation on the endocannabinoidome of metabolically relevant tissues from high-fat-fed mice. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2011; 8: 51.

Banni S, Carta G, Murru E, Cordeddu L, Giordano E, Sirigu AR et al. Krill oil significantly decreases 2-arachidonoylglycerol plasma levels in obese subjects. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2011; 8: 7.

Meye FJ, Trezza V, Vanderschuren LJ, Ramakers GM, Adan RA . Neutral antagonism at the cannabinoid 1 receptor: a safer treatment for obesity. Mol Psychiatry 2013; 18: 1294–1301.

Cluny NL, Vemuri VK, Chambers AP, Limebeer CL, Bedard H, Wood JT et al. A novel peripherally restricted cannabinoid receptor antagonist, AM6545, reduces food intake and body weight, but does not cause malaise, in rodents. Br J Pharmacol 2010; 161: 629–642.

Horswill JG, Bali U, Shaaban S, Keily JF, Jeevaratnam P, Babbs AJ et al. PSNCBAM-1, a novel allosteric antagonist at cannabinoid CB1 receptors with hypophagic effects in rats. Br J Pharmacol 2007; 152: 805–814.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by INSERM, Aquitaine Region, University of Bordeaux and University Hospital of Bordeaux.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gatta-Cherifi, B., Cota, D. New insights on the role of the endocannabinoid system in the regulation of energy balance. Int J Obes 40, 210–219 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.179

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.179

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

THC and CBD affect metabolic syndrome parameters including microbiome in mice fed high fat-cholesterol diet

Journal of Cannabis Research (2022)

-

Endocannabinoid signaling of homeostatic status modulates functional connectivity in reward and salience networks

Psychopharmacology (2022)

-

Hypothalamic endocannabinoids in obesity: an old story with new challenges

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2021)

-

The association of dietary patterns with endocannabinoids levels in overweight and obese women

Lipids in Health and Disease (2020)

-

A novel bioassay for quantification of surface Cannabinoid receptor 1 expression

Scientific Reports (2020)