Abstract

Background/Objectives:

The superiority of cholecalciferol (D3) over ergocalciferol (D2) in sustaining serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25OHD) levels is controversial. To compare D2 with D3 we performed a single-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial spanning 11 weeks.

Subjects/Methods:

Healthy volunteers (n=33, aged 33.4±6 years) were divided into three groups (n=11, each): D2, D3 and placebo. Treatment started with a loading dose (100 000 IU) followed by 4800 IU/day (d) between d7 and d20 and follow-up until d77. Serum samples were obtained at baseline and at days 3, 7, 14, 21, 35, 49, 63 and 77.

Results:

Baseline 25OHD values in the D2 group were lower than those in the D3 and placebo groups (P<0.01). Placebo 25OHD levels never changed. As after the loading dose both D2 and D3 groups had reached similar 25OHD levels, we tested equivalence of the area under the concentration × time curve (AUC) between d7 and d77. The AUC was 28.6% higher for D3 compared with D2, and both were higher with respect to placebo. At d77, D2 25OHD levels were higher than those at baseline, but similar to placebo; both were lower than D3 (P<0.04). According to raw data, the elimination half-life of 25OHD was 84 and 111 days under D2 and D3 supplementation, respectively; after subtracting the placebo values, the corresponding figures were 33 and 82 days.

Conclusions:

D2 and D3 were equally effective in elevating 25OHD levels after a loading dose. In the long term, D3 seems more appropriate for sustaining 25OHD, which could be relevant for classic and non-classic effects of vitamin D.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent worldwide1, 2 and increases the risk for several medical conditions, including osteoporosis, falls, cancer, diabetes, hypertension, autoimmune diseases so on.3, 4 This led to suppose that maintenance of adequate 25-hydroxy vitamin D (25OHD) levels in the blood is required for vitamin D regulation of a large number of physiologic functions beyond the classic actions on bone mineral metabolism.

Different regimens for prevention and correction of vitamin D deficiency have been proposed, but there is no universally accepted dose, frequency, route or type of vitamin D to use or to prescribe.5, 6, 7, 8

Two chemically distinct natural forms of vitamin D exist: ergocalciferol or vitamin D2 (D2) and cholecalciferol or vitamin D3 (D3). D3 is produced from 7-dehydrocholesterol in human skin exposed to UVB radiation and is present in a few foods (oily fish and egg yolk). D2 is sourced from UV irradiation of ergosterol, which is mainly found in fungi. Food and/or supplement intake may provide either D2 or D3. Both D2 and D3 function as prohormones through metabolism, first in the liver to 25OHD and later in the kidney, where 1α-hydroxylase converts 25OHD in the active metabolite 1, 25-dihydroxy vitamin D. This process is under homeostatic control.9

Serum 25OHD levels, including both 25OHD2 and 25OHD3, are the chief circulating forms of the vitamin and are representative of vitamin D status, reflecting D2 and D3 intake and cutaneous synthesis of D3. To date, the equivalence of D2 and D3 as well as their corresponding doses and administration route remains controversial.

Several reports, but not all, using highly different dosing regimens found D3 to be more effective than D2 in increasing or maintaining serum 25OHD levels.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 These reports used mainly only a type of supplementation: daily doses, between 1000 and 4000 IU,10, 11, 15, 17, 21 a single bolus or intermittent weekly or monthly high doses, with a range between 50 000 and 300 000 IU.12, 14, 16, 19 They had a variable follow-up (from 4 weeks to 1 year). A few of them involved a pharmacokinetic analysis12, 14, 19 and were controlled with placebo.15, 20

Taking into account such difficulties, and considering the importance of maintaining adequate 25OHD levels both for classic and for non-classic actions, and the heterogeneity of the published protocols, we designed the present pharmacokinetic study, including two sequential periods of administering D2, D3 and placebo as one single large loading dose, followed by maintenance daily doses, and later an elimination phase without vitamin D supplementation.

Subjects and methods

Study participants

Thirty-three healthy volunteers, 24–46 years old, either hospital employees or physicians, were recruited. None of them had a history of liver, kidney, malabsortive or granulomatous diseases, nor had they received corticosteroids, anticonvulsants or vitamin D supplements. All subjects were from Buenos Aires City (latitude 34ºS) and had limited sun exposure (<8 h/week). This protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Hospital de Clínicas José de San Martin (the teaching hospital of our university) and, according to current regulations, after approval it was communicated to Argentina's National Drug Regulatory Agency; all volunteers gave written informed consent. This placebo-controlled, parallel-group, randomized interventional study was designed to compare pharmacokinetic characteristics of the two main vitamin D natural forms, and not specific drug products.

Pharmacokinetic design

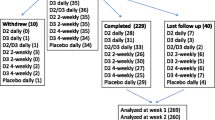

Participants were randomly assigned with a computer-generated code in a single-blind design to receive placebo (PLA), D2 or D3 in oral drops in the schedule presented in Figure 1: first, to boost vitamin D concentration, one single loading dose of 100 000 IU at the beginning of the study (baseline), followed by a daily dose of 4800 IU from days 7 to 20, and finally no vitamin D from days 21 to 77, to evaluate mainly the elimination phase. All subjects received an oral dose of 500 mg calcium (one calcium carbonate tablet/day) during the whole study. Fasting blood samples were collected at baseline and at days (d) 3, 7, 14, 21, 35, 49, 63 and 77. Two-hour urine fasting samples were collected at baseline and at d7, d21 and d77. Serum and urine samples were stored at −20 º C until processed.

Serum calcium and urine calcium and creatinine (Cr) were measured at baseline, d7 and d21 to evaluate the safety of bolus and daily doses. Hypercalcemia was defined as serum calcium >10.5 mg/dl and hypercalciuria as a ratio urine calcium/urine Cr >0.37 mgCa/mgCr.22 The trial ran from September to December 2010.

Procedure

The loading dose was administered by the physicians. Compliance to the vitamin D administration schedule was determined by measuring the residual volume (as number of drops) in the returned vials at day 21. D2 and D3 concentrations of the batches used, analyzed blindly by an independent laboratory using High Performance Liquid Chromatography with UV detection, confirmed the label values. The intake of vitamin D was determined by a nutritionist using a food frequency questionnaire.23

Analytical methods

Serum levels of 25OHD were determined by radioimmunoassay (DiaSorin, Stillwater, MN, USA). All serum 25OHD concentrations for a given individual were determined in a single assay to minimize variability. Intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variations were 6% and 8%, respectively. The quality and accuracy of 25OHD analysis were assured by a periodical participation in the Vitamin D External Quality Assessment Scheme (DEQAS). Levels of 25OHD <20 ng/ml were considered as deficient.24, 25, 26

Total and bone alkaline phosphatase (measured by agglutination with wheat germ lectin), intact parathormone, serum phosphorus and Cr were measured at baseline and at d77. Calcium, phosphorus, Cr and alkaline phosphatase were determined using standard methods21 and intact parathormone by electrochemical luminescence (ECLIA) (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

Pharmacokinetic and statistical analyses

Determination of pharmacokinetic parameters (Cmax, area under the concentration × time curve (AUC) and elimination half-life) and their statistical analysis were performed using WinNonlin Professional Software version 5.0 (Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA). Applying a noncompartmental model to the log-transformed plasma concentration of 25OHD, pharmacokinetic parameters (Cmax, AUC7–77) were compared by analysis of variance for a parallel design.27, 28 The Anderson and Hauck test were used to examine equivalence.29 The ratios and 90% confidence intervals of Cmax and AUC7–77 were calculated for D3/D2 and PLA/D2, and two one-sided t-tests30 were employed to evaluate whether the 90% confidence intervals met the criterion for bioequivalence (80–125%).28, 31 Other statistical analyses were nonparametric tests (Mann–Whitney and Wilcoxon) and analysis of variance (ANOVA), performed, as appropriate, with SPSS 11.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Significance level was 0.05.

Results

As shown in Table 1, the baseline anthropometric characteristics of the subjects of the three groups were similar, with the only exception being the body mass index in the PLA group, which was higher than the corresponding values in the D2 and D3 groups (P<0.01). The three groups had similarly low vitamin D intake from diet: 13 out of the 33 volunteers (39%) presented vitamin D deficiency. The D2 group presented baseline 25OHD values lower than the D3 and placebo groups (P<0.01) and with a higher number of subjects with vitamin D deficiency. There were no significant differences among groups with respect to any of the other biochemical parameters evaluated at baseline. Most subjects were adherent to protocol: the mean rates of compliance with treatment, on the basis of drop counts, was 88±10%, 92±7% and 85±9% for D3, D2 and PLA, respectively. Figure 2 presents the time course of 25OHD levels during treatment. The PLA group had no significant change in their 25OHD levels during the 77 days of follow-up. After the loading dose of 100 000 IU the 25OHD levels of both vitamin D groups had a rapid and similar increment at d3, which persisted at d7. The absolute increment over baseline was 20.3±10.5 ng/ml in D2 and 16.7±6.4 ng/ml in D3 (P=not significant), reaching similar 25OHD values (D2, 36.6.±11.0, and D3, 41.0±4.9 ng/ml; P=not significant). No patient who received the vitamin D loading dose (either D2 or D3) had 25OHD values in the deficiency range. The percentage increment between baseline and d7 was higher in subjects with basal 25OHD values <20 ng/ml than in those with baseline values ⩾20 ng/ml (179±68% vs 62±36%, P<0.0001). At d21, after the maintenance dose period, D2 and D3 25OHD levels were similar (33.8±9.2 and 41.9±8.6 ng/ml; not significant).

Pharmacokinetic analysis

We analyzed the geometric mean of Cmax during the course of the study, whereas for AUC we used AUC7–77 days, as at d7 both D2 and D3 groups had reached similar 25OHD levels after the loading dose administered at baseline. We performed an equivalence analysis to test whether the declined rate after stopping vitamin D supplementation was similar between groups, which is shown in Table 2, for Cmax and AUC, respectively. According to criteria commonly applied for equivalence, Cmax obtained by the loading dose of D2 and D3 was equivalent. In contrast, the Cmax for PLA (26.3 ng/ml) was lower than that for both D2 and D3, with a power of 76%. On the other hand, AUCs were not equivalent: neither the D3/D2 ratio nor the PLA/D2 ratio complied with criteria usually employed to check equivalence. The D3 AUC was 28.6% higher than the D2 AUC, and the PLA/D2 ratio was 71.84%, with a power of 71% in both cases (Table 2). D2 and D3 AUCs were higher than the PLA AUC. At the end of the protocol (d77), after 56 days without vitamin D supplementation, D2 25OHD levels were higher than at baseline, but similar to PLA, and both were lower than D3 (P<0.04; Figures 2 and 3). With the same software, their elimination half-lives were calculated with two different approaches: the direct value and after subtraction of the values corresponding to PLA.

The first approach resulted in a geometric mean for the elimination half-life of 25OHD of 84 and 111 days for 25OHD under D2 and D3 supplementation. The second approach (aiming to take into account the presence of vitamin D independent of the loading dose) resulted in values of 33 and 82 days, respectively, implying a shorter half-life for 25OHD2 than for 25OHD3.

Safety

No subject complained of treatment-related adverse events or experienced hypercalciuria or hypercalcemia at any of the measured points. Serum calcium and urine calcium/urine Cr did not differ in any group and no between-group differences were observed during the period of vitamin D administration (Table 3). The highest individual levels of 25OHD after D2 or D3 supplementation were lower than those associated with vitamin D intoxication. In every group, no difference between baseline and final levels was observed for serum calcium, serum phosphorus, serum Cr, alkaline phosphatase, bone alkaline phosphatase, intact parathormone and urine calcium/urine Cr (data not shown).

Discussion

Herein we have shown that under these experimental conditions vitamin D2 was as effective as vitamin D3 in increasing 25OHD levels with a loading dose. On the other hand, after a period with the same daily doses of vitamin D2 and D3, the 25OHD levels in the group that received vitamin D2 declined faster than the levels in the vitamin D3 group, reaching similar levels as the placebo group at the final point. This finding is consistent with and expands previous reports, providing additional elements to the current debate about vitamin D requirements and supplementation strategies, if required.

A central point for framing the discussion about the best supplementation is the understanding about the continuous or discontinuous need of some level of vitamin D in blood. In addition to the well-known effect on bone, vitamin D possesses pleiotropic actions on the immune and endocrine systems, and on common cell functions, such as proliferation and differentiation.4, 32 Most of these non-classic effects depend upon the tissue-specific regulation of 1,25(OH)2D, which requires adequate blood levels of 25OHD as substrate, suggesting that prolonged or continuous level of 25OHD could be worthwhile.

Many studies have analyzed the difference between vitamins D2 and D3, as well as the effect of dose, route and schedule of administration, over a wide range of ages and follow-up periods. In a recent meta-analysis33 cholecalciferol obtained a higher response than ergocalciferol in terms of increase and maintenance of 25OHD level. Our approach was to compare both calciferols in terms of concentration-time profiles after a loading dose and during a maintenance dose in the order recommended to sustain adequate levels in young adults, as well as in the elimination phase after withdrawal of maintenance.

Unexpectedly, the blind analysis of 25OHD of volunteers after randomization found a lower value in the D2 group, which prompted us to divide the analysis into two steps: the response to the loading dose and separately, after achieving similar levels of 25OHD, the comparison of both forms of vitamin D in the maintenance and elimination phases. The study began at the end of the Southern winter, and as previously reported many subjects (almost 40%) presented vitamin D deficiency, probably due to low vitamin D intake: only 20–25% of the RDA for adults24 and lower UV radiation in winter at this latitude.34, 35 The influence of solar radiation and spontaneous intake of vitamin D in the follow-up were probably limited, as the 25OHD levels almost did not change in the PLA group over the course of the study. Subjects were equally adherent to protocol and no safety problems were detected. As expected, the loading dose of either vitamin D quickly and markedly increased 25OHD levels at d3 and maintained them in the first week. Some of the reports, with follow-up up to a week after the loading dose, found persistence with both vitamins19, 20 and others only with vitamin D3.12, 14 Such discrepancies could involve several factors, including the size of the groups, intra-individual variation or non-registered vitamin D supplementation.6, 20 As a trend, the increase was higher in cases whose baseline values were lower. Further studies should determine whether compensatory mechanisms to accelerate vitamin D hydroxylation are involved. On the other hand, after reaching optimal values of 25OHD, maintenance doses of each vitamin D (4800 IU) effectively sustained those levels during the 14 days of supplementation. The dose used is very close to the daily utilization rate (4000 IU) reported for young adults at levels in the order of 32 ng/ml.36 25OHD plasma profiles after supplementation with either D2 or D3 are controversial: two reports, using the same dose level as us, found higher concentration values with vitamin D3, independently of the baseline value (whether deficient or not). In contrast, a report using 1,000 IU/day did not find any difference between D2 and D3.15 In our study, D3 AUC (a good measure of drug exposure after systemic administration) was 28% higher than D2 AUC. This finding was consistent, although lower, with previous reports with different loading doses and follow-up: all found higher AUC for D3 (between 56 and 340%).12, 14, 19 Consistent with previous reports, our main finding is the faster decrease in 25OHD serum concentration for D2 supplementation with respect to D3, resulting in a longer elimination half-life for 25OHD3. Such a difference can result from differences in the volume of distribution or in the clearance: both have been described for D2 and D3. The pharmacokinetics of vitamin D is highly complex and method limitation can add further complexity: for instance, RIA detects several 25-hydroxylated derivatives of vitamin D, such as 1,25(OH)2D, which, being relatively low and with a fast elimination, can marginally affect the values we measured. RIA does not distinguish between 25OHD2 and 25OHD3, although the sharp increase after the loading dose can logically be ascribed to the vitamin D (either D2 or D3) used. Moreover, as the time periods involved are long, many regulatory mechanisms can be in function. As to the volume of distribution (which is directly proportional to the elimination half-life) vitamin D Binding Protein depicts higher affinity for 25OHD3 than for 25OHD2.37, 38, 39 In healthy adults, supplementation with 50 000 IU/week of D3 produced 2 to 3-fold greater storage of vitamin D in subcutaneous fat biopsies than did equimolar D2.19 25OHD clearance is essentially determined by a highly complex network of metabolic transformations held in many different tissues. The main component40 is 1α-hydroxylation by CYP27B1, whose expression is upregulated by PTH and downregulated by its product 1,25(OH)2D. This active metabolite is short-lived, in part due to its high ability to induce CYP24A1, which is also detected in many organs. This enzyme can also metabolize 25OHD, although with an affinity that is one order lower. Hypothetically, such a lower affinity can become relevant at higher concentrations of substrate. Thus, differences in the metabolic rate by different enzymes, together with changes in the level of these enzymes, can be involved in our findings. Further studies are required to elucidate the relative contribution of each mechanism in vivo, at different dose levels of vitamins D.

A different AUC among vitamin D-supplemented subjects could be clinically relevant if adequate levels of 25OHD were continuously required. If this were the case, vitamin D3 use could be a better option. The rationale for a need of continuous 25OHD is currently insufficient, although some evidence suggests that such levels are worthwhile, in particular for non-classic vitamin D effects, which seem mediated via localized autocrine or paracrine synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D depending on the adequacy of 25OHD levels.4, 19, 32, 41 A lower tissue exposure to 25OHD after D2 supplementation should result in a proportionally lower synthesis of 1,25(OH)2D, in comparison with a similar dose of D3. However, further determinants can be also relevant; i.e. besides 25OHD level, the concentration of intact vitamin D delivered to tissues is important for 1,25(OH)2D synthesis, either for classic or for non-classic vitamin D effects.42

In summary, under these experimental conditions, loading doses of D2 or D3 were similar with respect to increasing 25OHD. After a maintenance period with the same daily doses, in the D2-supplemented group 25OHD levels declined faster than in the D3 group, reaching similar 25OHD levels than placebo at the final point. In the long term, vitamin D3 seems more appropriate to sustain adequate levels of 25OHD, which could be relevant for classic and non-classic effects of vitamin D.

References

Lips P . Worldwide status of vitamin D nutrition. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2010; 121: 297–300.

Mithal A, Wahl DA, Bonjour JP, Burckardt P, Dawson-Hughes B, Eisman JA et al. Global vitamin D status and determinants of hypovitaminosis D. Osteoporos Int 2009; 20: 1807–1820.

Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Dietrich T, Dawson-Hughes B . Estimation of optimal serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D for multiple health outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr 2006; 84: 18–28.

Bikle D . Nonclassic actions of vitamin D. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94: 26–34.

Trivedi DP, Doll R, Khaw KT . Effect of four monthly oral vitamin D3 (Cholecalciferol) supplementation on fractures and mortality in men and women living in the community: randomized double blind controlled trial. Br Med J 2003; 326: 469.

Mastaglia SR, Mautalen CA, Parisi MP, Oliveri B . 10.000 UI of oral vitamin D2 per day are required to rapidly reach adequate 25OHD levels in osteoporotic women. Eur J Clin Nutr 2006; 60: 1–7.

Pepper KJ, Judd SE, Nanes M, Tangpricha V . Evaluation of vitamin D repletion regimens to correct vitamin D status in adults. Endocr Pract 2009; 15: 95–103.

Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Shao A, Dawson-Hughes B, Hathcock J, Giovannucci E, Willet WC . Benefit - risk assessment of vitamin D supplementation. Osteoporos Int 2010; 7: 1121–1132.

Bikle D, Adams J, Christakos S . Vitamin D: production, metabolism, mechanism of action, and clinical requirements. In: Clifford Rosen (ed). Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism, 7th edn. American Society for Bone and Mineral Research: Washington, DC, USA, pp 141–149, 2008.

Tjellesen L, Hummer L, Christiansen C, Rodbro P . Serum concentrations of vitamin D metabolites during treatment with vitamin D2 and D3 in normal premenopausal women. Bone Miner 1986; 1: 407–413.

Trang HM, Cole DE, Rubin LA, Pierratos A, Siu S, Vieth R . Evidence that vitamin D3 increases 25-hydroxyvitamin D more efficiently than vitamin D2. Am J Clin Nutr 1998; 68: 854–858.

Armas LA, Hollis BW, Heaney RP . Vitamin D2 is much less effective than vitamin D3 in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004; 89: 5387–5391.

Rapuri PB, Gallagher JC, Haynatzki G . Effect of vitamin D2 and D3 supplement use on serum 25(OH)D concentration in elderly women in summer and winter. Calcif Tissue Int 2004; 74: 150–156.

Romagnoli E, Mascia ML, Cipriani C, Fassino V, Mazzei F, D́Erasmo E et al. Short and long term variations in serum calciotropic hormones after a single very large dose of ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) or cholecalciferol (vitamin D3) in the elderly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 3015–3020.

Holick MF, Biancuzzo RM, Chen TC, Klein EK, Young A, Bibuld D et al. Vitamin D2 is as effective as vitamin D3 in mantaining circulating concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 677–681.

Leventis P, Kiely PD . The tolerability and biochemical effects of high dose bolus vitamin D2 and D3 supplementation in patients with vitamin D insufficiency. Scand J Rheumatol 2009; 38: 149–153.

Glendenning P, Chew GT, Seymour HM, Guillet MJ, Goldsain PR, Inderjeeth CA et al. Serum 25 hydroxyvitamin D levels in vitamin D- insufficient hip fracture patients after supplementation with ergocalciferol and cholecalciferol. Bone 2009; 45: 870–875.

Biancuzzo RM, Young A, Bibuld D, Cai MH, Winter MR, Klein EK et al. Fortification of orange juice with vitamin D2 or vitamin D3 is as effective as an oral supplement in maintaining vitamin D status in adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 91: 1621–1626.

Heaney RP, Recker RR, Grote J, Horst RL, Armas LAG . Vitamin D3 is more potent than vitamin D2 in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96: E447–E442.

Binkley N, Gemar D, Engelke J, Gangnon R, Ramamurthy R, Krueger D et al. Evaluation of ergocalciferol or cholecalciferol dosing, 1600UI daily or 50000IU monthly in older adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96: 981–988.

Seijo M, Mastaglia SR, Brito G, Somoza J, Oliveri B . ¿Es equivalente la suplementación diaria con vitamina D2 o vitamina D3 en adultos mayores? Medicina 2012; 72: 195–200.

Vieth R, Chan PCR, Mac Fairline GD . Efficacy and safety of vitamin D3 intake exceeding the lowest observed adverse effect levels. Am J Clin Nutr 2001; 73: 288–294.

Brito GM, Mastaglia SR, Goedelman C, Seijo M, Somoza J, Oliveri B . Estudio exploratorio de la ingesta y prevalencia de vitamina D en mujeres mayores de 65 años que viven en hogar familiar o en residencias para autoválidos de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Nutrición Hospitalaria 2013; 28: 816–822.

IOM Dietary Reference Intake for calcium and vitamin D. The National Academies Press: Washington DC, 2011.

Bouillon R, Van Schoor NM, Gielen E, Boonen S, Mathieu C, Vanderschueren D et al. Optimal vitamin D status: a critical analysis on the basis of evidence-based medicine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98: E1283–E1304.

Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96: 1911–1930.

Hsuan FC . Estimating treatment means in a mixed-effect ANOVA model for bioequivalence studies. Biometrics1993 49: 703–713.

Chow SC, Liu JP . Design and analysis of bioavailability and bioequivalence studies. 2nd edn. Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2000.

Anderson S, Hauck WW . A new procedure for testing equivalence in comparative bioavailability and other clinical trials. Comm Statist Theory Methods 1983; 12: 2663–2692.

Schuirmann DJ . A comparison of the two one-sided tests procedure and the power approach for assessing the equivalence of average bioavailability. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 1987; 15: 657–680.

US Food and Drug Administration Guidance for Industry. Statistical approaches to establishing bioequivalence. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm070244.pdf. Last accessed on 15 October 2013.

Wacker M, Holick FH . Vitamin D. Effects on skeletal and extraskeletal health and the need for supplementation. Nutrients 2013; 5: 111–148.

Tripkovic L, Lambert H, Hart K, Smith CP, Bucca G, Penson S et al. Comparison of vitamin D2 and vitamin D3 supplementation in raising serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D status: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2012; 95: 1357–1364.

Ladizesky M, Oliveri B, Mautalen CA . Niveles séricos de 25-hidroxivitamina D en la población normal de Buenos Aires, su variación estacional. Medicina 1987; 47: 268–272.

Ladizesky M, Lu Z, Oliveri MB, San Román N, Holick M, Mautalen CA . Solar ultraviolet - B radiation and photoproduction of vitamin D in Central and Southern areas of Argentina. J Bone Min Res 1995; 10: 545–549.

Heaney RP, Davies KM, Chen TC, Holick MF, Barger-Lux MJ . Human serum 25-hydroxycholecalciferol response to extended oral dosing with cholecalciferol. Am J Clin Nutr 2003; 77: 204–210.

Hollis BW . Comparison of equilibrium and disequilibrium assay conditions for ergocalciferol, cholecalciferol and their major metabolites. J Steroid Biochem 1984; 12: 81–86.

Nimitphong H, Saetung S, Chanprasertyotin S, Chailurkit LO, Ongphiphadhanakul B . Changes in circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D according to vitamin D binding protein genotypes after vitamin D3 or D2 supplementation. Nutr J 2013; 12: 39.

Nilsson SF, Ostberg L, Peterson PA . Binding of vitamin D to its human carrier plasma protein 1972. Biochem Byophys Res Commun 1972; 46: 1380–1387b.

Schuster I . Cytochromes P450 are essential players in the vitamin D signaling system. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011; 1814: 186–199.

Spedding S, Vanlint S, Morris H, Seragg R . Does vitamin D sufficiency equate to a single serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level or are different levels required for non-skeletal diseases? Nutrients 2013; 5: 5127–5139.

Hollis BW, Wagner C . The role of the parent compound vitamin D with respect to metabolism and function: why clinical dose intervals can affect clinical outcomes. J Clin Endocr Metab 2013; 98: 4619–4628.

Acknowledgements

BO and SRM are members of the research career of CONICET (Argentina's National Research Council); JS is a member of support career of CONICET. We are indebted to the pharmaceutical companies Roemmers, Spedrog Caillon and Gador, which supplied the vials of Vitamin D2, Vitamin D3 and calcium, respectively. This research received financial support from grant PICT # 523 of Argentina's National Agency for the Promotion of Science and Technology (ANPCyT).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oliveri, B., Mastaglia, S., Brito, G. et al. Vitamin D3 seems more appropriate than D2 to sustain adequate levels of 25OHD: a pharmacokinetic approach. Eur J Clin Nutr 69, 697–702 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2015.16

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ejcn.2015.16

- Springer Nature Limited

This article is cited by

-

Maternal plasma vitamin D levels across pregnancy are not associated with neonatal birthweight: findings from an Australian cohort study of low-risk pregnant women

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2023)

-

Assessing the impact of a mushroom-derived food ingredient on vitamin D levels in healthy volunteers

Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition (2020)

-

CYP27A1, CYP24A1, and RXR-α Polymorphisms, Vitamin D, and Multiple Sclerosis: a Pilot Study

Journal of Molecular Neuroscience (2018)

-

Model-based meta-analysis for comparing Vitamin D2 and D3 parent-metabolite pharmacokinetics

Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics (2017)

-

The vitamin D deficiency pandemic: Approaches for diagnosis, treatment and prevention

Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders (2017)