Abstract

Since the 2000s, the number of immigrants has been growing in Brazil, as well as the cases of xenophobia. There are multiple explanations in the literature on the drivers of attitudes towards immigrants, which vary at the individual, regional and national analytical levels. We discuss and situate the argument of societal integration within the debate on whether social trust can reduce negative attitudes towards immigrants. We argue that social trust is key to reducing negative perceptions towards immigrants and a good predictor of attitudes in environments with strong perceived threat and prejudice, as is the case in Brazil. We empirically test whether greater generalized trust and trust in foreigners are related to a more positive attitude towards immigrants. Although this relationship has already been studied in other countries, to the best of our knowledge no study has yet been applied to the Brazilian case. Using data from the World Values Survey wave 7, and applying a logit model, our results corroborate that social trust has a positive impact on perceptions towards immigrants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The history of Brazil is marked by immigration. Colonized by Portugal [1], the country has been characterized as highly mixed, and has been populated by Italians, Japanese, Poles, Germans, Dutch, French, among others [2,3,4]. Although the data shows that immigrants, for the most part, choose the South and Southeast regions of Brazil [5], their presence is increasing in other regions, but with different profiles compared to past decades. In Recife, a city in Northeastern Brazil, it is common to find immigrants asking for money or food at traffic lights, an unlikely scenario in the first decade of 2000s. Up to 2011, the profile of foreigners in the country was mostly from the United States, Philippines, United Kingdom, India and Germany [6], while in 2022 they were from Venezuela, Haiti and Bolivia.

With the increase in the number of immigrants, discrimination became more frequent. One example of violence against immigrants was broadcasted in 2022: Moïse Kabahambe went to Brazil with his family in 2011 trying to escape from the civil war in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and was beaten to death after asking for his late wage [7].

Opinion polls show that Brazilians have little knowledge about the reality of immigration in the country. The latest data available found that Brazilians believe the percentage of immigrants, compared to the total population, is around 30%, when in reality it is 0.4% [8]. Although this percentage is still low compared to the United States, Germany, France (or even neighboring countries such as Argentina, Mexico and Chile), the number of immigrants living in Brazil is approximately 1.5 million, considering the most recent data available—an amount that grows every year [9].

Previous research has found that social trust can ease tensions between natives and immigrants [10, 11]. Nevertheless, most analyses have been conducted in European democracies and the United States [12]; thus, we still know very little about the relationship between trust and attitudes towards immigrants in developing countries. Despite the growing flow of immigrants to Brazil and other immigration flows in the Global South [13], to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study analyzing social trust impacts on attitudes towards immigrants in Brazil.

But why is it important to observe the Brazilian case? Here we consider six main reasons: Firstly, few studies on the topic. As the country is considered more an emissary than a recipient of immigrants, studies on immigration to Brazil have focused on the historical flow, immigrants’ quality of life and housing [14], and the role of social capital in individual labor incomes [15]. Secondly, changes in the flow of immigrants as traditional receptors make immigration more difficult. For instance, the United States and many European countries have increased their barriers to the entry of immigrants, especially since 2016 [16], which may cause them to look for other alternatives and countries [17]. Thirdly, the increase in flows to Brazil. Whether due to the linguistic proximity or less bureaucracy, immigrant flows towards Brazil have been steadily increasing since 2017 (see Fig. 1), and the country has recorded the largest number of Venezuelan immigrants in Latin America [18]. In fourth place, from a substantive point of view, migration has been a more salient topic within the social and political arenas. Since 2017, the crisis in Venezuela has led thousands of immigrants to enter the country, putting pressure on the public health system and worrying Brazilian authorities [19]. In fifth place, for economic reasons. Despite being behind countries like Mexico, Argentina, Chile and Uruguay in GDP per capita [20], the country is among the fifteen largest economies in the world [21] and has big cities, such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, that attract a considerable number of immigrants each year (see supplementary materials, figure S.1). Finally, due to Brazil’s low levels of social trust.

Social trust in Brazil is extremely low, even when compared to European countries with low trust rates or to other developing countries, such as South Africa. [13] has found that at least 51% of respondents believe that South Africans must be prioritized over immigrants when jobs are scarce, and 43% mentioned immigrants as undesirable neighbors. Comparatively, 93% of Brazilians declared they cannot trust most people [21]. Together, these six elements make Brazil an interesting case for migration literature.

Thus, this article aims to analyze if social trust can reduce negative attitudes towards immigrants. We hypothesize that greater generalized trust, as well as trust in foreigners, are related to a more positive attitude towards immigrants. Using the World Values Survey (WVS)Footnote 11 wave 7 (2017–2021), [22] we found a positive relationship, suggesting that social trust has an effect in reducing natives’ negative attitudes towards immigrants. The need to better understand this relationship is also crucial for policymakers, as it suggests that policies that encourage trust between natives and foreigners can reduce xenophobia in the country.

Section 2 frames our theoretical argument. The section also presents our testable hypotheses. Section 3 presents methodological aspects. Section 4 presents our empirical findings and Sect. 5 concludes our paper with our main considerations on the topic.

2 Theoretical framework and hypotheses

2.1 What drives attitudes towards immigrants?

The last decade has seen an increase in xenophobic discourses, especially in Europe and the United States. In 2015, during the presidential campaign, former president Donald Trump linked Mexican immigrants to problems such as drugs and crime [23]. In 2021, the French politician Marine Le Pen informed that, if she had won the presidential election, she would propose a referendum with strict criteria for immigrants who wanted access to French citizenship, social housing, employment, and social security benefits [24].

Such behaviors are not unique to developed countries. In 2018, on the eve of the elections, the governor of Roraima, Brazil, the state through which most Venezuelan immigrants pass, promised to close the border to immigrants. In short, immigrants are generally portrayed as an economic burden, responsible for encumbering the public machine through welfare programs, in addition to increasing local problems such as illegal drug trade and urban crime [25, 26].

There is not a unified theory of the drivers of attitudes toward immigrants. Multiple explanations are found in the literature, varying at individual, regional and national analytical levels. Our intention is not to present the state of the art in this topic, but to discuss and situate the argument presented in this work. [27] has identified at least eight predictors of attitudes towards immigrants: cultural marginality theory, human capital theory, political affiliation, societal integration, neighborhood safety, contact theory, foreign investment, and economic competition.

Starting with the cultural marginality theory, the argument is that greater cultural affinity leads to a more positive attitude towards immigrants. This theory assumes that immigration substantially modifies a country’s cultural structure. Such an impact is seen as a threat, as it would reduce national cultural characteristics in detriment of foreign characteristics [28]. In practical terms, according to this theory, when a citizen feels that his culture is being threatened by the increase in the immigration flow, that person tends to respond negatively in relation to immigrants [29].

The human capital theory states that the level of education is a good predictor of attitudes. Under this perspective, more educated people do not feel that they need to compete with immigrants for jobs, which would lead to a less negative attitude [30]. In a famous study, [31] show that more educated respondents are less racist and believe that immigration has beneficial effects on the economy.

The third theory, political affiliation, suggests that left-wing people have more positive attitudes towards immigrants than those to the right of the political spectrum [32]. [32] analyzed whether the presence of immigrants in Austrian communities affected voting for the far-right party Freedom Party of Austria (Freiheitliche Partei Osterreichs, FPÖ). The authors found that the party’s share of votes increased from 5% in the 1980s to 27% in the late 1990s. This percentage remained constant and the party attracted more than 20% of voters in the 2013 national elections. Furthermore, the authors found that the number of votes for the FPÖ increased in regions with greater immigration flows. In another study, [33] conducted a natural experiment in the Aegean islands, and tested whether exposure to refugees increases support for far-right parties. The authors show that, in municipalities and cities that experienced a sudden increase in the flow of immigrants, electoral support for the far-right parties increased.

The fourth theory, that of neighborhood safety, is linked to the uncertainties brought to society that are attributed to immigrants. The argument is based on the belief that foreigners, being supposedly poorer, tend to look for crime as an alternative to social ascension [34]. Thus, high rates of violence and crime would be associated with immigrants, and would generate a sense of insecurity. This theory is measured by how safe citizens feel walking around their neighborhood at night.

The fifth theory, contact theory, was originally formulated by [35]. It argues that greater contact between natives and immigrants can reduce aversion and negative attitudes. The idea is that, the more we acquire knowledge of “others”, the more we assimilate and empathize with them [36]. According to this perspective, regular contact between different groups could stimulate affective bonds, which could in turn help reduce negative perceptions [37].

The sixth and seventh theories use economic arguments as guiding attitudes. In the case of foreign investment, world-system theories imply that migration is a consequence of the process of resource and human capital exploitation by rich countries. When citizens of rich countries are informed by the media about these countries and the difficult conditions their citizens face, sensitivity increases, and more positive attitudes result. Economic indicators like per capita income and unemployment rate serve as the basis for the theory of economic competition. Lower-skilled workers would tend to express more negative attitudes out of fear that immigrants increase job competition and take their jobs [38].

Finally, our study is supported by the societal integration theory, which uses social trust as a predictor of attitudes. Under this perspective, when citizens have more trust towards each other and/or towards institutions, negative perceptions of immigrants decrease [39]. In the supplementary materials (table S.1) we provide a table with the eight key predictors used in this theory, as well as the level of measurement and references. In the next section we dive deeper into this debate and present our argument.

2.2 Social trust and attitudes towards immigrants

The conceptualization of social trust is a hard task. Studies prefer to approach social trust through its characteristics rather than by presenting a conclusive definition [40]. In general, social trust can be characterized by feelings of security and trust in the good intentions and good will of others [41]. The existence of trust implies the absence of perceived threat [42], where both sides seek out the best interests of each other and aim to achieve similar results [43]. Yet social trust can manifest itself in different ways. One can trust their parents, but not trust politicians, for instance; i.e., trust is not a unified feeling that is applied indistinctly. As it is a multidimensional concept, research identifies at least two types of social trust: particularized and generalized [44]. Particularized trust applies to people close to a person’s social life (e.g., friends and family), while generalized trust is abstract and encompasses people or groups that are not close or are not fully known to each other (for example, acquaintances). Thus, it is expected that trust is higher towards those who are closer [39].

As trust is a central element in human relationships—to the point that [45] claim it is a requirement for a cohesive society—there is a growing amount of studies on the topic. Yet much still needs to be explored regarding social trust as a predictor of attitudes towards immigrants [46]. When constructing our argument we took the advice of [47], who suggest caution when observing that the literature operationalizes social trust both as an effect (dependent variable) and as a cause (independent variable).

Some studies assume that the social heterogeneity brought about by immigration has a negative impact on the levels of social trust [40]. In other words, the greater the physical contact with people of another race or ethnic origin, the more we would become attached to ours and the less we would trust others [48,49,50,51,52,53]. This controversy, as recalled by [54], focuses mainly on the argument that diversity is obstructive to the creation of social trust. A possible explanation for this argument is that, in heterogeneous communities, citizens trust and feel more comfortable interacting with people who are similar in terms of income, race and ethnicity [55, 56]. Thus, trust would thrive in homogeneous communities but fail in heterogeneous ones.

Most of the empirical literature has, in fact, corroborated this [57]. [53], for example, argues that those living in heterogeneous areas exhibit less trust. [58], controlling for age and educational level, concluded that social trust is lower in heterogeneous communities. Similar results have been found by other authors (see, for instance, [40, 55, 59,60,61,62].

These studies suggest that homogeneous societies are more fertile for the development of trust. However, there are few studies dedicated to studying the inverse relationship—social trust impacting attitudes towards immigrants—and there is limited empirical evidence accessing this relationship [63]. [47], for example, using data from the European Social Survey (2002 round), found that citizens with a higher degree of trust have more positive attitudes than the rest of the population. This is confirmed by [64], who used data from European Values Study and found that particularized and generalized trust are linked to lower levels of religious and racial prejudice.

In short, when social trust is used as an effect, the relationship found tends to be negative, whereas when it is analyzed as a cause it tends to present a positive relationship. Nevertheless, there are exceptions. For example, in an experiment in Germany, [65] found not only a strong and negative impact of ethnic diversity on trust, but that a greater stimulus to ethnic and religious heterogeneity led to a lower level of respondents’ trust in their neighbors. On the other hand, analyzing the impact of social trust on attitudes towards immigrants, [63] found that it had a positive impact both in and within European countries, even when controlling for different social factors.

We argue that social trust is central to reducing negative perceptions towards immigrants and a good predictor of attitudes in environments with strong perceived threat and prejudice, as is the case in Brazil. Our argument is also supported by studies such as that of [66]: even after including different contextual variables, these authors found a positive effect of social trust in all models (see also 27). Considering the two levels of social trust detailed above, our first hypothesis is that generalized trust will have a positive relationship on attitudes towards immigrants in Brazil:

Hypothesis 1

The greater the generalized trust, the higher the positive attitudes towards immigrants.

Applying the same argument to the particularized level, we hypothesize that greater trust in people of other nationalities is able to reduce aversion and perceived threat and lead to more receptive behavior:

Hypothesis 2

The greater the trust in foreigners, the higher the positive attitudes towards immigrants.

3 Data and method

3.1 Data source

We used data from the WVS wave 7 (2017–2021), Footnote 2 a high-quality database produced since 1981, which explores topics such as individual values and beliefs and their impact on people’s lives. The database encompasses over 100 countries, covering almost 90% of the world population. Topics explored include support for democracy, religion, globalization, the environment, family, culture and diversity, with multiple analytical possibilities. In the case of this wave, the WVS has a specific immigration question session Footnote 3 In Brazil, 1,762 people participated in wave 7. The sample covered all regions, especially where the immigration flow is greater and the theme is more salient, such as São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais (the three richest Brazilian states). The percentage of men and women was balanced, but only 9 of the 1,762 people were immigrants. The percentage is low, but consistent and representative of the real population.

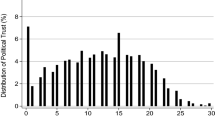

3.2 The dependent variable— attitudes towards immigrants

We measured attitudes towards immigrants using the following question: “From your point of view, what have been the effects of immigration on the development of this country? For each of the following statements about the effects of immigration, please, tell me whether you agree or disagree with it. [Increases unemployment]”. The variable has two alternatives: (1) Agree, and (2) Disagree. The option (3) Hard to say is only checked if the respondent mentions it, but it is not read by the interviewer. The question captures a realistic threat commonly associated with immigrants: the perception that they increase competition for jobs and steal jobs from natives, increasing local unemployment. As mentioned in the supplementary material, the answer 3 was grouped with agreement. The scales recoding, described in supplementary materials, table S.2, indicate the highest value indicating disagreement with the statement.

3.3 The independent variable—social trust

Following [44], we separate social trust into two categories: generalized and particularized. To measure generalized trust, we use the classic question “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or you can’t be too careful?”. The question has two alternatives: (1) most people can be trusted, and (2) need to be very careful. In turn, we chose the category of people of other nationalities to capture particularized trust, which became the variable trust in foreigners. The question asks whether the respondent trusts people of other nationalities, and provides four alternatives: (1) trust completely, (2) trust somewhat, (3) do not trust very much, and (4) do not trust at all. This variable was recoded into a dummy variable, isolating those who trust completely and somewhat, from those who do not trust very much or at all.

3.4 Control variables

We also controlled for widely consolidated variables as predictors for attitudes. We included economic and socio-demographic characteristics, such as Age, Female, Level of education, Unemployed, and Income. Previous studies have shown that younger, more educated, employed and higher-income people have more positive attitudes toward immigrants [67]. We also included Ideology, to verify if left-wing people are more positive about immigrants. Table 1 shows that the number of observations for Ideology was much lower than for the other characteristics, which suggests respondents’ difficulty in placing themselves in the political-ideological spectrum.

3.5 Analytical strategy

Survey data analysis techniques, collected from representative samples, date from the nineteenth century. They have guided the socio-political and economic debate in several dimensions, by providing concrete data on numerous facets of social reality, from the occupancy rates of jobs to public opinion on various topics that support the political process [68]. Despite focusing on complex samples, [68] present a comprehensive approach to the elaboration and analysis of research data and specific statistical methods described that can be applied to different types of survey. Although many surveys are only a descriptive and data collection tool about a population, the proper statistical treatment of observational data makes it possible to explore and expand the understanding of multivariate relationships in the target population to investigate causality between variables of interest.

There are several ways and models for analyzing survey data [68]. Here, our dependent variable was modeled as a dummy, applying a logit model. Logistic regression is used to predict the probability of category membership on a dependent variable based on multiple independent variables. The independent variables can be either dichotomous (i.e., binary) or continuous (i.e., interval or ratio in scale). According to Stock and Watson [69] the logit model is:

Here Yi is the dependent variable defined in categories 0 (agree or hard to say) and 1 (disagree), while ꞵ measures the influence of X covariates on the probability of the occurrence of Y, and k, the total of correlated linearly independent. Three models guide our empirical analysis. Model 1 considers the two variables associated with social trust and ideology. We isolated ideology due to the low percentage of observations in the sample, which could interfere with the other results. Models 2 and 3 exclude ideology and include other control variables. The logit coefficients are best interpreted by computing predicted probabilities [70].

4 Results

Table 2 reports the results of the model, where attitudes towards immigrants are measured by the belief that they increase unemployment. Column 1 presents the first model, including widespread trust and foreigners, controlling for ideology. The results show that greater social trust reduces the chances of the respondent having a negative attitude. With regards to ideology, our results support studies that show great differences of attitudes towards immigrants according to a person’s location on the political-ideological spectrum [32, 33]. Immigration has been one of the main ideological platforms of far-right parties, which commonly include anti-immigration policies in their programs. These parties and their politicians benefit and garner many votes by raising concerns among voters that a greater influx of immigrants could bring about economic and cultural harm [71].

The second model includes two more controls. The results confirm that people with higher income are more likely to have a positive perception of immigrants than those with lower income people. A possible explanation may lie in the perception of risk [54]. People with low incomes are more socially vulnerable, and have a greater sense of uncertainty than those with greater financial stability. Thus, immigration tends to be seen as a risk, or as something that will worsen their situation. The results also suggest that younger people tend to express more positive attitudes towards immigrants. Figure 2 illustrates these results: respondents aged 17–40 tended to disagree with the statement that immigrants increase unemployment, when compared to other age groups. The results align with [72], who analyzed 25 countries.

Finally, our third model includes the other controls. The two variables associated with social trust maintained their significance. Both confirmed our expectations that greater generalized and particularized trust positively impact attitudes towards immigrants, reducing the perception that they increase unemployment. Figure 3 illustrates this relationship. Although education had a positive effect on attitudes towards immigrants, the coefficient was not statistically significant, in line with studies like that of [13]. As mentioned earlier, previous studies have shown that higher levels of formal education are associated with a more positive perception of immigrants [31]. Two possible explanations can be cited. The first is that people with less education fear a risk of growing labor competition more than those that are highly educated. Second, a higher level of education is associated with greater knowledge of the world, diversity and interaction with strangers, which could lead to less fear of the unknown [11].

This model also showed that individuals who identify as left-wing are more unlikely to express negative attitudes toward immigrants. The literature has found ambiguous results regarding this association. Some studies argue that this association occurs both due to a common feeling of social justice, equality and multiculturalism [73] and a lower perception of danger and competition [74]. In other words, people who identify as left-wing tend to fear the unknown less and identify more with others in vulnerable situations. However, this relationship is not unanimous. After analyzing 21 European and Anglo-Saxon countries between 1972 and 2012, [75] concluded that there is no clear association between political orientation and anti-immigration behavior.Footnote 4

Another finding of this model was that individuals with an unfavorable economic situation are more likely to oppose immigration in Brazil. As recalled by [13], it is not the objective competition with immigrants that causes this attitude, but the perceived threat. Subjective feelings can cause the belief that increased immigration leads to greater competition in the labor market, and that immigrants would be able to steal jobs from natives [54]. Thus, this perceived threat is feared more by people who already lack an adequate income. Such aversion to immigrants is understandable in the Brazilian case, where at least 31% of the population lives in poverty [76].

The literature also considers age as a determinant of attitudes towards immigrants, and similar results were found in this study. We found that in Brazil older people tend to express more concern about the possible negative effects of immigration than younger people. At least one study highlights generational differences and the impact of information over time [77], as younger people tend to be more informed and to assimilate changes more quickly. However, [78] state that it is not possible to consider age as an analytical factor isolated from context. In other words, it is not just a matter of stating that past generations are more cautious about immigration, but of the historical times and events that helped shape this perception.

Surprisingly, in contrast to an established literature confirming a relationship between higher education and positive attitudes (see 31), we found no evidence of this relationship. Studies about Europe and the United States attest that the number of years of formal education impacts the perception of immigrants. Our findings, however, agree with similar studies carried out in South Africa, Russia, and some Asian countries, where no effect of education was reported [13, 79].

5 Concluding remarks

How can social trust influence attitudes towards immigrants? After broadly assessing the most important theoretical approaches to attitudes towards immigrants and the main aspects the literature points out regarding the idea of social trust, we analyzed the impact of generalized and particularized social trust on attitudes towards immigrants in Brazil. More specifically, we analyzed whether it reduces the belief that immigrants increase unemployment among natives. We hypothesized that the greater the generalized (H1) and particularized (H2) trust, the more positive the attitude. In the empirical analysis, we applied a logit model. Although this relationship has been widely studied in developed countries, our study contributes to the scarce literature on developing countries, such as [13] and [79], who have analyzed the South African and Russian cases, respectively.

In general, our findings corroborate previous literature on the topic by pointing out that the level of income of a country might not make a difference when it comes to attitudes towards immigrants (although this could be another avenue for a future research agenda). In addition to testing and finding evidence for political and economic hypotheses, which the literature identifies as important factors on attitudes, we also verified the role of age. Nevertheless, in the last case we are aware that context may also matter. For instance, generational differences and the impact of information over time might play a role on attitudes. Younger people may also be more informed and adaptable to changes, and historical events and societal context could shape perceptions. Finally, this study found no evidence of links between higher education and positive attitudes toward immigrants, which came as a surprise and contradicted other studies.

Similar mechanisms that shape attitudes towards immigrants in developed countries and South Africa also seem to apply to Brazil. The country is marked by high social inequality and poverty, which might lead the most vulnerable to have negative attitudes towards immigrants. As in South Africa, recent historical contexts may have had impacts still felt today, as the country faced years of military rule and authoritarian leadership in different moments of the twentieth century. However, the impact of these events on the perception of immigrants still needs to be tested. As in the study by [13], higher social trust seems to be linked to lower levels of anti-immigrant attitudes. As citizens have more trust, whether in general or towards people of other nationalities, the chance of believing that immigrants are bad for their country decreases. As already observed by [53], trust seems to promote environments of greater tolerance and assimilation. Considering this fact, and applied to the Brazilian case, our results give strong support to the work of [47]: if the goal is to reduce ethnic-social tensions, investing in social trust may be a very good idea.

Data availability

The data analyzed is available at https://osf.io/hbsqd/

Notes

The most recent wave of the World Values Survey (7) started in mid-2017 in several countries (cross-section) and followed a 1-year postponement due to the Covid-pandemic. It was finally closed on December 31, 2021. Subsequent WVS waves are planned every five years; WVS-8 is planned for 2024-2026. The 7th wave continued monitoring cultural values, attitudes and beliefs towards gender, family, and religion; attitudes and experience of poverty; education, health, and security; social tolerance and trust; attitudes towards multilateral institutions; and cultural differences and similarities between regions and societies. In addition, the WVS-7 questionnaire included new topics such as the issues of justice, moral principles, corruption, accountability and risk, migration, national security, and global governance. More information can be found at: https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSContents.jsp. Here we used the results for Brazil.

To download the 2017–2021 WVS dataset, please see the link https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV7.jsp.

This is an advantage of WVS compared to other databases that include Brazil, such as AmericasBarometer, which has limited questions on immigration issues.

For a robustness test see the appendix (table S.3).

References

Fausto B. História do Brasil. São Paulo: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo; 2019.

Schwarcz LM, Starling HM. Brasil uma biografia. Companhia das Letras: São Paulo; 2015.

De Holanda SB. Raízes do Brasil. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras; 2015.

Ribeiro D. O Povo Brasileiro A Formação e o Sentido do Brasil. São Paulo: Global Editora; 2015.

Reznik L. História Da Imigração No Brasil. São Paulo: FGV Editora; 2020.

Assad L. Nova onda de estrangeiros chega ao Brasil. Ciência e Cultura. 2012;64(2):11–3.

Veja. 2022. Congolês espancado até a morte será homenageado com memorial no Rio. https://veja.abril.com.br/brasil/congoles-espancado-ate-a-morte-sera-homenageado-com-memorial-no-rio/.

Ipsos. 2018. Perigos da percepção 2018 https://www.ipsos.com/pt-br/perigos-da-percepcao-2018.

UN DESA. 2019. International migrant stock 2019. Available at: http://bit.ly/3pYChA7.

Macdonald D. Political trust and support for immigration in the American mass public. Br J Politic Sci. 2020;4:1–19.

Sipinen J, Söderlund P, Bäck M. The relevance of contextual generalised trust in explaining individual immigration sentiments. Eur Soc. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1762909.

Igarashi A, Laurence J. How does immigration affect anti-immigrant sentiment, and who is affected most? A longitudinal analysis of the UK and Japan cases. Compar Migration Stud. 2021;9(24):1–26.

Ruedin D. Attitudes to immigrants in South Africa: personality and vulnerability. J Ethn Migr Stud. 2019;45(7):1108–26.

Jorgensen NV, Barbieri AF, Guedes GR, Zapata GP. International migration and household living arrangements among transnational families in Brazil. J Ethnic Migration Stud. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1707646.

Barros AR, de Mesquita CS. The role of social capital on individual labor incomes in Brazil. Planejamento e Políticas Públicas. 2009;32:37–56.

Center for Migration Studies. 2020. President Trump’s executive orders on immigration and refugees. https://cmsny.org/trumps-executive-orders-immigration-refugees/.

Bertino Moreira J. Refugee policy in Brazil (1995–2010): achievements and challenges. Refug Surv Q. 2017;36(4):25–44.

UNHCR. 2020. Brasil torna-se o país com maior número de refugiados venezuelanos reconhecidos na América Latina. https://www.acnur.org/portugues/2020/01/31/brasil-torna-se-o-pais-com-maior-numero-de-refugiados-venezuelanos-reconhecidos-na-america-latina/.

Arruda-Barbosa L, Sales AFG, de Souza ILL. Reflexes of Venezuelan immigration on health care at the largest hospital in Roraima, Brazil: qualitative analysis. Saúde e Sociedade. 2020;29(2):1–11.

World Bank. 2020. GDP per capita (current US$) - Latin America and Caribbean. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?end=2020andlocations=ZJandstart=2020andview=chart.

World Bank. 2020a. Gross domestic product 2020. Available at: https://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/GDP.pdf.

World Values Survey. 2021. World Values Survey Wave 7 (2017–2020). https://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV7.jsp

Washington Post. 2015. Donald Trump’s false comments connecting Mexican immigrants and crime. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/fact-checker/wp/2015/07/08/donald-trumps-false-comments-connecting-mexican-immigrants-and-crime/

Reuters. 2021. France’s Le Pen proposes referendum on immigration if elected president. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/frances-le-pen-proposes-referendum-immigration-if-elected-president-2021-09-27/.

Dancygier R. Culture, context, and the political incorporation of immigrant-origin groups in europe. In: Hochschild J, Chattopadhyay J, Gay C, JonesCorrea M, editors. Outsiders No More? Models of Immigrant Political Incorporation. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. p. 119–36.

Green D. The trump hypothesis: testing immigrant populations as a determinant of violent and drug-related crime in the United States. Soc Sci Q. 2016;97(3):506–24.

Rustenbach E. Sources of negative attitudes toward immigrants in Europe: a multi-level analysis. Int Migr Rev. 2010;44(1):53–77.

Zárate MA, Garcia B, Garza AA, Hitlan RT. Cultural threat and perceived realistic group conflict as dual predictors of prejudice. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2004;40:99–105.

Stephan WG, Ybarra O, Martinez CM, Schwarzwald J, Tur-Kaspa M. Prejudice towards immigrants to Spain and Israel: An integrated threat theory analysis. J CrossCultural Psychol. 1998;29:559–76.

Mayda AM. Who is against immigration? a cross-country investigation of individual attitudes toward immigrants. Rev Econ Stat. 2006;88(3):510–30.

Hainmueller J, Hiscox MJ. Educated preferences explaining attitudes toward immigration in Europe. Int Organ. 2007;61:399–442.

Halla M, Wagner AF, Zweimüller J. Immigration and the voter for the far right. J Eur Econ Assoc. 2017;15(6):1341–85.

Dinas E, Matakos K, Xefteris D, Hangartner D. Waking up the golden dawn: does exposure to the refugee crisis increase support for extreme-right parties? Polit Anal. 2019;27(2):244–54.

Reid LW, Weiss HE, Adelman RM, Jaret C. The immigration-crime relationship: evidence across us metropolitan areas. Soc Sci Res. 2005;34(4):757–80.

Allport G. The nature of prejudice. Oxford: Addison-Wesley; 1954.

Pettigrew TF, Tropp LR. When groups meet: dynamics of intergroup contact. New York: Psychology Press; 2011.

Guan Q, Pietsch J. The impact of intergroup contact on attitudes towards immigrants: a case study of Australia. Ethn Racial Stud. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2021.2007277.

Aydemir A, Borjas GJ. A comparative analysis of the labor market impact of international migration: canada, mexico, and the United States. J Eur Econ Assoc. 2007;5(4):663–708.

Freitag M, Bauer PC. Testing for measurement equivalence in surveys. dimensions of social trust across cultural contexts. Pub Opinion Quart. 2013;77:24–44.

Delhey J, Newton K. Predictin cross-national levels of social trust global pattern or Nordic exceptionalism. European Sociol Rev. 2005;21(4):311–27.

Tropp LR, et al. The role of trust in intergroup contact: its significance and implications for improving relations between groups. In: Wagner U, et al., editors. Improving intergroup relations: building on the legacy of thomas F pettigrew. New York: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2008.

Stephan WG, Stephan CW. An integrated threat theory of prejudice. In: Oskamp S, editor. Reducing prejudice and discrimination. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2000. p. 23–45.

Tyler TR. Public trust and confidence in legal authorities: What do majority and minority group members want from the law and legal institutions? Behav Sci Law. 2001;19(2):215–35.

Newton K, Zmerli S. Three forms of trust and their association. Eur Polit Sci Rev. 2011;3(2):169–200.

Schiefer D, van der Noll J. The essentials of social cohesion: a literature review. Soc Indic Res. 2017;132:579–603.

Chang HI, Kang WC. Trust, economic development and attitudes toward immigration. Can J Polit Sci. 2018;51(2):357–78.

Herreros F, Criado H. Social trust, social capital and perceptions of immigration. Political Studies. 2009;57:337–55.

Blumer H. Race prejudice as a sense of group position. Pacific Sociol Rev. 1958;1:3–7.

Giles MW, Evans A. The power approach to intergroup hostility. J Conflict Resolut. 1986;30:469–85.

Brewer MB, Brown RJ. Intergroup Relations. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of Social Psychology, 4th. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998.

Hallberg P, Lund J. The business of apocalypse: robert putnam and diversity. Race and Class. 2005;46(4):53–67.

Bobo LD, Tuan M. Prejudice in politics: group position, public opinion and the wisconsin treaty rights dispute. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2006.

Putnam RD. E pluribus unum: diversity and community in the twenty-first century the 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scand Polit Stud. 2007;30(2):137–74.

Coffé H, Geys B. Community heterogeneity: a burden for the creation of social capital? Soc Sci Q. 2006;87(5):1053–72.

Knack S, Keefer P. Does social capital have an economic payoff? A cross-country investigation. Q J Econ. 1997;112(4):1251–88.

Alesina A, La Ferrara E. Participation in heterogeneous communities. Quart J Econ. 2000;115(3):847–904.

Dinesen PT, Schaeffer M, Sønderskov KM. Ethnic diversity and social trust: a narrative and meta-analytical review. Annu Rev Polit Sci. 2020;23:441–65.

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–24.

Glaeser EL, Laibson DI, Scheinkman JA, Soutter CL, Soutter. Measuring Trust. Quart J Econ. 2000;115:811–46.

Costa DL, Kahn,. Civic engagement and community heterogeneity: an economist’s perspective. Perspect Polit. 2003;1(1):103–11.

McCulloch A. An examination of social capital and social disorganization in neighborhoods in the british household panel study. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:1425–38.

Soroka S, Johnston R, Banting Keith. Ethnicity, trust and the welfare state. In: Kay F, Johnston R, editors. Social Capital, Diversity and the Welfare State. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press; 2006.

Mitchell J. Social trust and anti-immigrant attitudes in Europe: a longitudinal multi-level analysis. Front Sociol. 2021;6: 604884.

Ekici T, Yucel D. What determines religious and racial prejudice in Europe? The effects of religiosity and trust. Soc Indic Res. 2015;122(1):105–33.

Koopmans R, Veit S. Ethnic diversity, trust, and the mediating role of positive and negative interethnic contact: a priming experiment. Soc Sci Res. 2014;47:91–107.

Manevska K, Achterberg P. Immigration and perceived ethnic threat: cultural capital and economic explanations. Eur Sociol Rev. 2013;29(3):437–49.

Facchini G, Mayda AM. Does the welfare state affect individual attitudes toward immigrants? evidence across countries. Rev Econ Stat. 2009;91(2):295–314.

Heeringa, S. G., Brady T. W., and Berglund, P. A. Berglund. 2020. Applied Survey Data Analysis, Second Edition: CRC Press, 2020.

Stock, J. H. and Watson, M. W. 2019. Introduction to Econometrics, Global Edition. Pearson Education Limited.

Long JS, Freese J. Regression models for categorical dependent variables using stata. Texas: Stata Press; 2014.

Mudde C. The war of words. Defining the extreme right party family. West Eur Polit. 1996;19:225–48.

Schotte S, Winkler H. Why are the elderly more averse to immigration when they are more likely to benefit? evidence across countries. Int Migrat Rev. 2018;52(4):1–33.

Joon Han K. When will left-wing governments introduce liberal migration policies? an implication of power resources theory. Int Stud Quart. 2015;59:602–14.

Semyonov M, Raijman R, Yom Tov A, Schmid P. Population size, perceived threat, and exclusion: a multiple-indicators analysis of attitudes toward foreigners in Germany. Soc Sci Res. 2004;33:681–701.

De Haas, H. and Nasser, K. 2015. The determinants of migration policies. Does the political orientation of governments matter? IMI working paper series, 117. https://www.migrationinstitute.org/publications/the-determinants-of-migration-policies-does-the-political-orientation-of-governments-matter.

IBGE. 2023. Pobreza cai para 31,6% da população em 2022, após alcançar 36,7% em 2021. https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-noticias/2012-agencia-de-noticias/noticias/38545-pobreza-cai-para-31-6-da-populacao-em-2022-apos-alcancar-36-7-em-2021#:~:text=O%20percentual%20de%20pessoas%20em%20extrema%20pobreza%2C%20ou%20seja%2C%20que,9%2C0%25%20em%202021.

Wilkes R, Corrigall-Brown C. Explaining time trends in public opinion: attitudes towards immigration and immigrants. Int J Comp Sociol. 2011;52(1–2):79–99.

Munck I, Barber C, Torney-Purta J. Measurement invariance in comparing attitudes toward immigrants among youth across Europe in 1999 and 2009: The alignment method applied to IEA CIVED and ICCS. Sociol Methods Res. 2018;47(4):687–728.

Alexseev M. The asymmetry of nationalist exclusion and inclusion: migration policy preferences in Russia, 2005–2013. Soc Sci Q. 2015;96(3):759–77.

Funding

Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

As corresponding author, WS was responsible for the whole article, since the initial idea, as well as the main argument, theoretical framework, data and method, and discussion of the results. EA helped creating the data and method section, as well as discussing which regression model would fit better to our model. She also analyzed the theoretical framework and discussion of the results sections. AS helped not only with English revisions, but also with the main argument of the manuscript. She also helped with the theoretical framework and discussion of the results. CM helped with the data and method section, as well as regression models and discussion of the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

dos Santos, W.M., Steiner, A.Q., Alves, E.E.C. et al. Assessing the impact of social trust on attitudes towards immigrants: evidence from Brazil. Discov glob soc 2, 63 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s44282-024-00079-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s44282-024-00079-z