Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) decision-making systems are already being extensively used to make decisions in situations where legal rules are applied to establish rights and obligations. In the United States, algorithmic systems are employed to determine the rights of individuals to disability benefits, to evaluate the performance of employees, selecting who will be fired, and to assist judges in granting or denying bail and probation. In this paper I explore some possible implications of H. L. A. Hart’s theory of law as a system of primary and secondary rules to the ongoing debate on the viability and the limits of an adjudicating artificial intelligence. Although much has been recently discussed about the potential practical roles of artificial intelligence in legal practice and assisted decision making, the implication to general jurisprudence still requires further development. I try to map some issues of general jurisprudence that may be consequential to the question of whether a non-human entity (an artificial intelligence) would be theoretically able to perform the kind of legal reasoning made by human judges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) decision-making systems are already being extensively used to make decisions in situations where legal rules are applied to establish rights and obligations. In the United States, algorithmic systems are employed to determine the rights of individuals to disability benefits, to evaluate the performance of employees, selecting who will be fired, and to assist judges in granting or denying bail and probation.Footnote 1 Both noteworthy and controversial, these are only a few examples of a growing trend, but most of them can be fairly reduced to sophisticated systems of selection among sets of predefined options—sets of coordinated rules to solve a given operation, refined by probabilistic models.

In this paper I intend to explore some possible implications of H. L. A. Hart’s theory of law as a system of primary and secondary rules to the ongoing debate on the viability and the limits of an adjudicating artificial intelligence. Although much has recently been discussed about the potential practical roles of artificial intelligence in legal practice and assisted decision making, the implication to general jurisprudence still requires further development. Here, I try to map some issues of general jurisprudence that may be consequential to the question of whether a non-human entity (in this case an artificial intelligence) would be theoretically able to perform the kind of legal reasoning made by human judges, addressing the prospects of how automated judicial decision-making systems could be brought about as progressions from current auxiliary decision-making systems and decision prediction models.Footnote 2

The answer to this question depends on (i) a theory about what the law is, (ii) a correspondent understanding of the cognitive process taking place when judges decide cases applying laws to facts (legal reasoning); and (iii) whether an algorithmic entity is or will ever be able to perform this kind of cognitive process, i.e., to perform legal reasoning.

An affirmative answer, therefore, would require a formal concept of law that can be represented in a way that allows for an algorithmic entity, satisfying certain conditions, to perform cognitive processes indistinguishable from a human judge performing legal reasoning when adjudicating cases presented before him or her. I argue that Hart’s thesis is a good starting point to shed some light on these issues.

2 Hart’s model of rules

The British legal theorist H. L. A. Hart presents in the book The Concept of Law a theory of law as ultimately reducible to a system of rules that remains to this day at the core of orthodox positions in terms of established jurisprudence in legal positivism.Footnote 3 First published in 1961, the seminal work in which Hart aims to “further the understanding of law, coercion, and morality as different but related social phenomena”Footnote 4 persists to this day as “the most important and fundamental” restatement of legal positivism.Footnote 5

Under positivism’s social thesis, the content of a law is identifiable by reference to the social facts that entail its source.Footnote 6 In its strong version, the thesis implies that a test for determining the existence and the content of the law depends exclusively on “facts of human behavior capable of being described in value-neutral terms.”Footnote 7 Supporters of the social thesis as foundational to the positivist thinking about the lawFootnote 8 usually argue, for its justification, with descriptive precision: it correctly reflects the meaning of ‘law’ and cognate terms in ordinary language, it separates the description of the laws from its evaluation, and it eliminates, or minimizes, the investigator’s bias.Footnote 9

In said book, Hart undertakes an essentially descriptive account of the law as a social phenomenon. His goal is to arrive at a definition of law that is general and universally applicable, one that is consistent with the generality of the uses of the word law in different cultures and societies. Hart refines the traditional positivist doctrine of law as essentially a command,Footnote 10 regarded both inadequate and insufficient as a descriptive stance. In his view, the concept of law cannot be reduced to the notion of mere commands backed by threats if it is to function as an accurate description of the whole complexity of the legal system. At least not without a significant loss of meaning and, thus, descriptive power. There is much that is distorted in a legal system, he notes, if described as a commandFootnote 11 as, for instance, leaving no place for the notion of rights.Footnote 12 The attempted translation of all legal phenomena into the language of commands is misleading and distorts instead of illuminating.

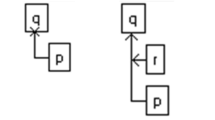

He argues, instead, that to recognize an enactment as law, all that is needed is to establish that “it was made by a legislator who was qualified to legislate under an existing rule”.Footnote 13 From there, Hart postulates the rule of recognition as the first and foremost type of what he calls a secondary rule. Together with rules of change and rules of adjudication, the rule of recognition is, in his view, a crucial element by which a legal system differs from a proto-legal regime of primary rules.

Hart asserts that understanding the legal system as a combination of two types of rules—primary and secondary—is “the key to the science of jurisprudence.”Footnote 14 The union of primary rules of obligation with secondary rules characterizes a legal system, as opposed to pre-legal normative structures.Footnote 15 Primary rules require human beingsFootnote 16 to “do or abstain from certain actions,” while secondary ones provide that, by performing certain acts, they “introduce new rules of the primary type, extinguish or modify old ones, or in various ways determine their incidence or control their operations.”Footnote 17

Hart proposes three different forms of secondary rules, which he calls rules or recognition,Footnote 18 rules of changeFootnote 19 and rules of adjudication.Footnote 20 Each type of secondary rule operates as a remedy for one of three defects—uncertainty, inflexibility, and inefficiency—inherent to a hypothetical regime made of primary rules alone—the rules requiring human beings to do or to abstain from certain conduct.

Rules of recognition, the argument goes, are the institutional devices that allow, within a legal system, for other legal rules to be acknowledged as such (as valid, operative, applicable etc.) in opposition to rules that are not recognized as part of that system: from merely moral rules to rules belonging to a different jurisdiction. As Dworkin synthesizes, “the root idea is that the truth of propositions of law is in some important way dependent upon conventional patterns of recognizing law”.Footnote 21 Once recognized, the rule is apt to be enforced as a legal rule. Arguably a cognitive mechanism by which one recognizes which rule governs each conduct, the rule of recognition furnishes the legal system with the feature of legal certainty. Rules of change—the second type—design the procedures by which new primary rules are created or modified, ensuring the dynamism of the legal system.Footnote 22 The third type of secondary rules—rules of adjudication—empower entities to authoritatively determine “whether, on a particular occasion, a primary rule has been broken.”Footnote 23 The rules of adjudication identify adjudicating entities, like judges, courts, arbiters etc., and define the procedure to be followed.

Although Hart describes the rules of adjudication as “empowering individuals”Footnote 24 and “identifying individuals who are to adjudicate”,Footnote 25 I argue that there is nothing in their nature preventing a non-human entity, like an artificial intelligence, from being assigned as an adjudicating entity, provided that the cognitive requirements to be able to perform legal reasoning are fulfilled. As legal reasoning, I refer to the capability of consistently operating rules of recognition, rules of change and primary rules to produce a result that is not only consistent with what we expect from human judges but is also generated through processes that mirror human judges’ cognitive operationsFootnote 26 when they convey meaning.Footnote 27

If Hart’s theory is true and the structure resulting from the combination of primary rules of obligation with the secondary rules of recognition, change and adjudication” is the “heart of a legal system,”Footnote 28 then the reproduction of this theoretical structure in the form of an algorithmic model should be the goal of the development of adjudicating algorithms. To work properly, an adjudicating AI would have to properly articulate the structural role of primary and secondary rules, i.e., to learn how to use the language of law.

3 Towards a model of rules for AI

Legal rules provide for definite, predictable and officially recognized consequences for a deviation from a required conduct.Footnote 29 Hart states that laws performing roles as different as criminal laws prohibiting certain conducts and testamentary laws conferring powers to individuals constitute, ultimately, standards by which particular actions are measured against and attributed consequences accordingly.”Footnote 30

When courts decide on issues presented before them, they must enunciate (recognize) what is the rule of the case.Footnote 31 Judges and courts employing primary rules and rules of change and adjudication rarely if ever expressly state the rules of recognition governing this cognitive activity. Its existence is rather implied, “shown in the way in which particular rules are identified, either by courts or other officials or private persons or their advisers.”Footnote 32 Judges know the law, after all. Accordingly, for an adjudicating computational system, the rule of recognition means the implementation of an algorithm by which the rule or rules to be applied in a case are consistently identified. Such an algorithm would have to evaluate parameters like the validity of rules, jurisdiction setting, statute of limitations, hierarchy of laws, and factors excepting a rule or modifying the way it applies to a given case. It would have to scan all the rules in the legal system and apply the recognition parameters to conclusively identify the primary rule governing the case. Implemented by an algorithmic model, the rule of recognition is declared in the programming code, as a set of parameters providing for the identification of particular cases as instances of general hypothesis, distinguishing capability, and knowing where to find the law to apply and how to read and interpret it. Supplied with the rules for their treatment and an initial set of values, the system would have to refine and adapt these parameters through learning.

An adjudicating artificial intelligence would also have to articulate the consequences of operative rules of change to properly access the rights and duties that are created or extinguished when the law is reshaped. This means the capability of properly identifying and applying changes to the legal framework: the legal effects of abrogation of laws, new legislation, overruling of precedents etc. These tasks require that at least the rules allowing these operations are previously built into the system. Current AI judicial systems are trained by data mining of previously defined datasets,Footnote 33 typically.

consisting of structured collections of case law, legal codes and statutes.Footnote 34 This technological standard has an inherent static inclination, and a system trained on an outdated dataset progressively becomes inaccurate as referred to the current legal environment. Such a system, untrained or ill-trained on what is now the current valid legal standard, is an inaccurate judge. A more dynamical architecture, however, would probably mean a system more open to data input, raising concerns about system security.

In a chapter of The Concept of Law where he discusses the relation between laws and morals, Hart points out what he calls characteristic judicial virtues, implying that judges who appropriately display these attributes when deciding to exercise an activity qualitatively distinct from legislating.Footnote 35 They are:

[i] impartiality and neutrality in surveying the alternatives; [ii] consideration for the interest of all who will be affected; and [iii] a concern to deploy some acceptable general principle as a reasoned basis for decision.Footnote 36

According to the model, a judicial decision exhibiting such features can be considered “the reasoned product of informed impartial choice.”Footnote 37 The fact that Hart does not dedicate much to the topic of procedure, nor does he further develop a discussion on the theory of adjudication, rather focusing on the relation between rules, institutions and human behaviors, leaves the field open to speculation on the substance of the properties required from an adjudicating entity. When it comes to adjudicating AI, I argue that it can, at least in theory, make decisions that are reasoned, informed and impartial. A reasoned decision is one in which the applicable rule is identified according to consistent parameters in a satisfactory and explainable way.Footnote 38 An informed decision takes into the equation and properly weights all the relevant facts and interests affected. This ability relies on a granular analysis of relevant case law by machine-learning algorithms.Footnote 39 An impartial decision is one in which no subjective interest or preference of the adjudicating entity, either conscious or unconscious, plays any role. Parameters providing for all these characteristics can be embedded into algorithmic models. Whether they can or should choose an outcome when there is no single one available from mere rule application raises particular concerns.Footnote 40

4 Algorithmic decision

In our current digital culture, we tend to associate the concept of an algorithm itself with one particular usage: the incorporation of algorithmic models in programming code that makes a digital computer perform tasks we assign them. But we have been using algorithms for thousands of years to perform various activities, from fishing to baking cakes. When performing standardized tasks, making a diagnosis, applying a method to solve a problem, applying a rule to a fact and checking the outcome, in all these activities we are thinking algorithmically. Generally speaking, an algorithm is nothing more than a finite set of instructions that, applied to a given set of data, produces a predictable result, “a procedure that allows us to solve a problem without having to invent a solution each time.”Footnote 41 In this sense, it is possible to understand a criminal code, with its definitions of specific crimes, aggravating factors and extenuating circumstances, requirements of culpability etc., as an algorithm that, when applied by the magistrate (computer) to a given set of data (the specific case), produces, as result, a valid verdict from a normative point of view. From a conceptual standpoint, therefore, a simple algorithm contemplating the finite set of parameters and variables present in a criminal code, operated by a human intelligence provided with the necessary information, is able in theory to accurately carry on with the judgment of a criminal case.

A computer algorithm consists of a specific class of pre-programmed applications that, fed with a collection of data, offers a precise response. Algorithmic decision-making models are trained to find patterns in data through a process called machine-learning.Footnote 42 Machine-learning algorithms, in particular, are trained, validated and tested with input from training datasets: in the case of an artificial intelligence, sets of data (e.g., cases, laws, precedents) from which the algorithm “learns”. The more a machine-learning algorithm runs the provided data, the more mistakes and successes are referred to as parameters for further refinement. Thus, the algorithm is able to return a progressively more accurate response as additional data is offered.

An especially complex class of algorithms currently going through a period of fast improvement comprises the cognitive models: computational models that approximate human cognitive processes, simulating sophisticated behaviors. Because their architecture emulates the structure of a biological brain, they are also called neural networks.Footnote 43 This structure allows mathematical representations of possibilities and probabilities to mirror human capabilities of reasoning and inference,Footnote 44 thus performing processes that may be described as analogous to the ones of weighting and balancing rules and principles,Footnote 45 at least when we assume Hart’s model of rules as the blueprint of legal reasoning.Footnote 46 For instance, it has been demonstrated that computational models performing probabilistic inferences over certain types of structured data can achieve results that are generative in a way similar to language acquisition.Footnote 47 If it shows effective in articulating legal principles and legal rules, further development of judicial probabilistic models will make the case for Hart’s rejection of a sharp contrast between legal principles and legal rules,Footnote 48 in favor of a distinction as a matter of degrees of certainty and abstraction.

By reducing the law to a system of rules, Hart comes to a description of the legal system that is analogous to an algorithm—a set of coordinated rules to solve a given operation. Moreover, although criticizing Hans Kelsen’s account of law as orders to officials to apply sanctions,Footnote 49 Hart concedes that all types of legal rules can be iterated in the conditional form, so that the general conditions under which courts are to apply rules are essentially ‘if-clauses’ (if x then y).Footnote 50 If true, this proposition, combined with the development of cognitive computer models, is highly consequential to the viability and reach of an adjudicating artificial intelligence.

To be assimilated into an algorithmic model of automated adjudication comparable to adjudication by human judges, law’s structure needs, at least, to be first described in a way that is sufficiently objective and abstract to amount to an algorithm. At a minimum, Hart’s model of rules provides crucial insights to guide the translation of law’s grammar and syntax into the language of the machines.

5 Legal reasoning

Hart acknowledges that there is a lot more to the law then what happens at the courts, and although he is much more concerned with the social role of the law,Footnote 51 the problem at issue here is typically one related to how the law is applied by judges. Hart observes that litigation and prosecutions are ancillary, yet vital provisions that come into place when the legal system fails to assure its observance.Footnote 52 It is intuitive to us that these provisions constitute human entities—judges and courts composed by judges—to solve the inevitable conflicts that arise around the application of the law. There is no discrepancy with the model, however, if a law constitutes a different entity to perform the adjudicating role, at least for some types of cases, even though a non-human one (like an artificial intelligence), provided that it proves able to perform the same kind of reasoning that judges do when they decide cases, as discussed above.

Human language and cognition have been effectively described as the implementation of particularly complex algorithms for assembling hierarchical symbols.Footnote 53 As a linguistic artifact, law is also a symbolic system or mode of communicationFootnote 54 and, as such, also implements algorithms.Footnote 55 Procedural law, for instance, is an algorithm to allow lawyers and judges to adjudicate cases in a standardized, predictable way, as are the tests devised by courts to answer if a fact pattern falls under the scope of a previous ruling. If laws are algorithms, they are independent of the specific language in which they are encodedFootnote 56 and therefore can be translated into a machine readable language.

To perform the same type of reasoning a judge does when applying a rule to a fact, an adjudicating entity must be able to assimilate, with a high degree of accuracy, the particular description of a fact to the abstract and general hypothesis conveyed in the rule, be it a rule requiring or prohibiting a conduct (imposing a duty or obligation) or a rule conferring certain rights on individuals.Footnote 57 The very structure of legal argument is theoretical, i.e., it is abstraction. In this sense, applying a rule to a case is an exercise of abstraction, requiring no particular imaginative or creative skill beyond the cognitive process mentioned above (the implementation of an algorithm to assemble hierarchical symbols).Footnote 58 Even when operating on defeasible arguments and inconsistent information, legal reasoning can still be modeled as a process of deriving and comparing arguments.Footnote 59 Judges learn the algorithm by going to law schools and studying statutes and precedents. Once they know the laws’ algorithm, the abstract standard, they apply it to the particular cases before them.

6 Incompleteness and rule creation

A formal system is said to be consistent when no proposition can be proven true and false at the same time. It is said to be complete when every proposition in it can be proven true or false. Finally, a system is decidable when there is at least one effective method to prove every proposition true or false.Footnote 60 With his incompleteness theorems, Kurt Gödel showed not only that no formal language can be proven simultaneously consistent, complete and decidable, but that these properties exclude one another. I argue that these conclusions hold true when tested against legal systems, though this is not in the scope of this exploration.Footnote 61

As a matter of consequence, existing legal systems can be treated as always incomplete artifacts with an open texture. They never contemplate all the justifiable standards, nor do they necessarily encompass all social rules and conventions, comprising at any given moment of only a subset of those with the proper institutional connection.Footnote 62 Not surprisingly, judges often find that the legal system does not always provide a clear rule to solve a case. In this situation, they typically generate the rule to be applied, using one or more methods of interpretation or justification. If an artificial intelligence is developed and trained to imitate the cognitive process human judges do when performing legal reasoning, it is fair to speculate that, when deciding a case using a set or subset of all the legal rules and standards recognized by a given legal system, an outcome corresponding to the generation of a new rule is a possibility. The emergence of a new rule resulting from an algorithmic process analogous to legal reasoning would not be inconsistent with Hart’s account of legal rules having modes of origin that differ from orders.Footnote 63 In his model, will, or explicit prescription, is not an essential feature of rules’ modes of origin,Footnote 64 as Hart observes regarding rules originating in customs, which also do not owe their legal status to any conscious law-creating act.

In theory, the postulation of a new rule might happen in at least two distinct ways: (i) as the result of an analytical process by means of which the new rule not previously stated is derived, extrapolated and made explicit; or (ii) by an authoritative choice not derived from other rules, but from political, moral, ideological or other standards. In the first case, the process can be fairly described as law discovery or law development. In the second case, as actual law-making. While human judges both apply the law (using legal skills) and develop the law (with external input),Footnote 65 an adjudicating AI based on machine-learning will hardly be able to perform the latter, for the same reason that it is not equipped to propose the overruling of a standard.Footnote 66

Consistent with the model, there is nothing preventing algorithms from being trained to recognize and apply typical methods of legal interpretation. However, when rigorous interpretation achieves its limits, so does the machine. Because algorithms can only solve problems that are computable or decidable,Footnote 67 they can apply rules according to predefined parameters, but they cannot arbitrarily choose nor create them. Undecidable problems, for which the legal system does not provide a rule, are non-computable and therefore undecidable. Any step forward, made by a human judge, would be a choice. Made by a machine, a dice roll.

As long as the answer to a case is available within the domain of legal reasoning, machines could eventually perform all that judges do when deciding cases presented before them. If, however, there are legal questions that are undecidable using only the parameters provided by the law, there is at least a set of cases that demand a choice informed by extralegal factors.

Although they can be designed with an intention in mind, algorithms do not have intention themselves.Footnote 68 As long as we do not expect judges to make use of this faculty, algorithms could also do the job. The moment an intentional choice not reducible to law application becomes inevitable, algorithms may have to step back, although they could be designed to flag these undecidable cases.

7 Conclusion

The debate on whether machines can or should perform the kind of work we usually attribute to judges and courts is often highly mystified, surrounded by misconceptions and prejudices with pinches of sci-fi-driven anxiety. To avoid such distractions, I tried to narrow the focus of this exploration to the question on whether a non-human entity (in particular an artificial intelligence) would theoretically be able to perform the kind of legal reasoning made by human judges, but there is a lot more that can be explored: repercussion of adjudicating AI to the relation between law and moral, in what sense the inclusive legal positivism paradigmFootnote 69 would challenge the theoretical model of an adjudicating AI, the extent to which a probabilistic model can accurately emulate balancing of legal principles, algorithmic bias, algorithmic opacity and the rule of law, system accountability, system safety, fairness, explainable vs. interpretable AI models etc.

To the very large extent of law that consists of “determinate rules which, unlike the applications of variable standards, do not require from them a fresh judgment from case to case”,Footnote 70 increasing adoption of artificial intelligence adjudication may represent social gains of certainty and efficacy. Reducing human discretion favors consistency among decisions, making the adoption of automated decision tools especially invaluable, but not without caveats like overreliance in machine outputs (automation bias).Footnote 71 Adjudicating artificial intelligence can decide complex matters but cannot make free choices. Pervasiveness of decision making by artificial intelligence has the potential to make the judicial landscape more stable (as opposed to uncertain) and effective, but at the price of more becoming more static (as opposed to dynamic). Potentially better than us to remedy the defects of uncertainty and inefficiency in a legal system, an adjudicating AI is, conversely, worse than us to deal with the problem of static.

Notes

See [5].

See [2].

Jeremy WALDRON acknowledges this paradigmatic status of the model of rules when challenging on of its key elements: “The rule of recognition is … a central component of modern positivist jurisprudence.” [18].

See [11].

See [7].

See [15].

Id. at 39–40.

Id. at 41.

Id. at 42.

See [10].

Id. at 602.

Id. at 605.

HART. supra note 3, at 70.

Id. at 81.

Id. at 94.

Even when the addressees of rules are non-human or collective entities, like unions, states, corporations or intelligent machines, rules still ultimately determine acts to be performed or avoided by human beings.

HART. supra note 3, at 81.

Id. at 94.

Id. at 95.

Id. at 97.

DWORKIN. supra note 4, at 35.

HART. supra note 3, at 96.

Id. at 96.

Id.

Id. at 97.

See [3].

See [12].

HART. supra note 3, at 98.

Id. at 10.

Id. at 33.

Id. at 95.

Id. at 101.

See [13].

See [6].

HART. supra note 3, at 205.

Id.

Id.

HILDEBRANDT. supra note 26, at 23.

Id.

See [20].

See [1].

See [16].

Id. at 161.

Id.

See [9].

HILDEBRANDT. supra note 26 at 19.

See [17].

HART. supra note 3, at 261.

Id. at 35–7.

Id. at 36.

Id. at 40.

Id.

See [4].

Id at 53.

Consistent with this picture of legal rules, legal institutions can in turn be described as consisting of “informational processes” organized around exchanges of legal information. See ABITEBOUL & DOWEK. supra note 33, at 82.

ABITEBOUL & DOWEK. supra note 33, at 36.

HART. supra note 3, at 27–8.

BERWICK & CHOMSKY. supra note 52 at 53.

See [14].

Here, I try a parallelism with David Hilbert’s formalist program in mathematics.

HART discusses the essential incompleteness of legal rules when making his case about the problems of the penumbra. See supra note 9, at 612.

RAZ. supra note 5, at 45.

HART. supra note 3, at 79.

Contrary to Hans Kelsen, who insists that norms are always originated from acts of will.

RAZ. supra note 5, at 48.

Assuming that the adjudicating AI in not supplied with, nor it articulates, moral, ideological, political or other standards beyond those assimilated and encoded into the legal corpus.

ABITEBOUL & DOWEK. supra note 33, at 36.

Id. at 2.

See [19].

HART. supra note 3, at 135.

See [8].

References

Abiteboul, S., Dowek, G.: The Age of Algorithms, vol. 6. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2020)

Ash, E.: Judge, Jury, and EXEcute file: the brave new world of legal automation (2018)

Bathaee, Y.: Artificial intelligence opinion liability. Berkeley Technol. Law J. 35, 113–152 (2020)

Berwick, R.C., Chomsky, N.: Why Only Us: Language and Evolution, vol. 132. MIT Press (2016)

Crawford, K., Schultz, J.: AI systems as state actors. Columbia Law Rev. 119, 1941–1943 (2019)

D’Almeida, A.C.: The Future of AI in the Brazilian Judicial System: AI mapping, integration, and governance. SIPA Capstone 12–13 (2021)

Dworkin, R.: The Law’s Empire, vol. 34 (1986)

Engstrom, D.F., Ho, D.E.: Algorithmic accountability in the administrative state. Yale J. Regul. 37, 800–807 (2020)

Garcez, A.S.d'A., Gabbay, D.M., Lamb, L.C.: A neural cognitive model of argumentation with application to legal inference and decision making. J. Appl. Logic. 12, 109–125 (2014)

Hart, H.L.A.: Positivism and the separation of law and morals. Harv. L. Rev. 71, 593–601 (1957)

Hart, H.L.A.: The Concept of Law. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2012)

Hildebrandt, M.: Law as computation in the era of artificial intelligence: speaking law to the power of statistics. Univ. Toronto Law J. 68, 12–26 (2018)

Oswald, M., Grace, J., Urwin, S., Barnes, G.C.: Algorithmic risk assessment policing models: lessons from the Durham HART model and ‘Experimental’ proportionality. Inf. Commun. Technol. Law 27, 223–235 (2018)

Prakken, H.: Logical Tools for Modeling Legal Argument: A Study of Defeasible Reasoning in Law. Springer, Berlin, pp. 275–280 (1997)

Raz, J.: Legal positivism and the sources of law. In: The authority of law: Essays on law and morality, pp. 37–47 (1979)

Reich, R., Sahami, M., Weinstein, J.M.: System Error: Where Big Tech Went Wrong and How We Can Reboot. Hodder and Stoughton, p. 82 (2021)

Tenenbaum, J.B., Kemp, C., Griffiths, T.L., Goodman, N.D.: How to grow a mind: statistics, structure, and abstraction. Science 6022, 1279–1281 (2011)

Waldron, J.: Who needs rules of recognition? In: Adler, M. & Himma, K.E. (eds.) The rule of recognition and the U.S. Constitution, vol. 327 (2009)

Waluchow, W.: Inclusive Legal Positivism. Clarendon Press, Oxford, p. 80 (1994)

Williams, R.: Rethinking Deference for Algorithmic Decision-Making. Oxford Legal Studies Research Paper No. 7/2019 (2018)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Canalli, R.L. Artificial intelligence and the model of rules: better than us?. AI Ethics 3, 879–885 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-022-00210-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43681-022-00210-3