Abstract

Results from panel regressions on a new dataset of government revenue windfalls and shortfalls in EU Member States demonstrate that macroeconomic developments have a significant impact on cyclically adjusted fiscal outcomes and indicators. In particular, the results show that an increase in household debt results in higher government revenue windfalls, while a higher trade balance leads to government revenue shortfalls. These revenue windfalls and shortfalls have distorted the signals from fiscal indicators that are used to measure the ‘underlying’ fiscal position and the governments’ fiscal efforts to improve debt sustainability. The paper also finds that temporary windfall revenues trigger permanent increases in government spending or decreases in tax rates. Taking account macro-economic indicators, such as the trade balance and private debt, provides relevant complementary information for medium-term budgetary planning, budgetary rules and surveillance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The 2008 financial and sovereign debt crisis drew attention to the fact that large fluctuations in government revenues beyond those explained by fluctuations in GDP may have a major impact on fiscal outturns and public finance prospects. Before the 2008 crisis, several EU Member States had experienced a build-up of macroeconomic imbalances, including in trade balances, property prices and private debt. While building up, these imbalances generated large windfall revenues, which governments spent in the absence of national and EU governance instruments detecting their temporary nature. As imbalances and the associated windfall revenues reversed, they amplified the effect of the cyclical downturn itself on fiscal outcomes. Reversing excessive expenditure growth (and tax cuts) that were based on windfall revenues proved difficult in the downturn, leading to large and persistent fiscal imbalances and protracted adverse impacts on growth and employment caused by austerity.

The effects of macroeconomic and financial sector developments on fiscal outcomes are not limited to the financial crisis and its aftermath. Large revenue windfalls and shortfalls occur every year in the Member States, and trigger debates on the appropriate fiscal response.Footnote 1 They result in particular from changes in tax bases and effective tax rates that relate to macro-financial developments. Tax base effects beyond GDP stem from factors such as financial transactions (property), stock variables (wealth, property prices) or capital inflows. In addition, impacts on effective tax rates may result from price developments in the context of nominal tax brackets.Footnote 2

A better understanding of the link between macroeconomic and financial developments (that go beyond the cyclical effects as captured by the output gap) and revenue windfalls and shortfalls can provide insights into their likely permanent or temporary nature. This may better inform fiscal planning and surveillance.Footnote 3 This paper analyses the extent to which fluctuations in budgetary elasticities resulting from those macroeconomic developments can be better captured, to improve the understanding of the underlying fiscal positions and fiscal stance.

Empirical literature on the effects of macroeconomic developments on fiscal indicators and outcomes is scant due to data challenges. This paper elaborates on the literature by introducing a dataset of revenue windfalls and shortfalls, by netting out the impact of discretionary revenue measures. This dataset allows identifying the effects of macroeconomic developments on fiscal indicators. The novelty of focusing on government revenues, while netting out of discretionary policy measures, gives a clean measure of the direct fiscal impact of macroeconomic developments that is not polluted by policy reactions, and reduces estimation challenges due to endogenous effects of fiscal policy on macroeceonomic variables.Footnote 4

We demonstrate how consideration of macroeconomic developments and deviations from estimated equilibriaFootnote 5 can improve the understanding of the fiscal outcomes by capturing their estimated effects in a panel analysis, and illustrate the extent to which it has affected fiscal outcomes in EU Member States since 2000. To that end, we proceed in two steps. A first step is to estimate the sensitivity of fiscal outcomes to macroeconomic developments on top of those linked to the economic cycle. This part of the analysis investigates the extent to which macroeconomic developments that are not reflected in GDP may be drivers of revenue windfalls and shortfalls. In the second step, the estimated elasticities of that empirical analysis are used to illustrate the potential impact over time of macroeconomic developments on fiscal indicators.

The structure is as follows. Section “Literature review” discusses the scant empirical literature and presents the conceptual framework more in detail. Section “Methodology to assess the effects of macroeconomic developments on fiscal indicators” presents the regression analysis and results of the effects of macroeconomic developments on revenue windfalls and shortfalls. Based on those findings of the regression analysis, Sect. “Results of the empirical analysis” shows the extent to which the consideration of macroeconomic developments and deviations from equilibrium values can help improve understanding of the underlying fiscal position.

Literature review

Due to data challenges and challenges related to endogenous effects of fiscal policy on macroeceonomic variables, only a few empirical studies have investigated the link between macroeconomic developments and fiscal indicators. Those studies suggest that the assessment of the fiscal position, fiscal stance and fiscal risks should more explicitly consider budgetary fluctuations linked to macro-economic and financial developments in addition to the output gap. More broadly, the existing literature looks at either the impact of macroeconomic developments that are potentially associated with external imbalances (e.g. current account developments) or that of the financial cycle (often associated with internal imbalances, e.g. housing prices developments) on public finance indicators. No comprehensive analysis exists that covers the impact of a broad range of macroeconomic developments together.Footnote 6

Overall, the relevant literature can be broadly categorised into three groups based on the type of imbalances considered: external, internal and prices. It is presented below, and Table 1 at the end of the section provides a summary of its findings. Figure 1 shows a conceptual framework that illustrates the channels through which macroeconomic variables may affect public revenue and expenditure and helps understanding the scope of the relevant literature. It breaks down (i) cyclical effects, (ii) discretionary fiscal policies (that depend on many factors) and (iii) the cyclically-adjusted expenditure and revenue, net of discretionary policies (our focus). We focus on the effect on public revenue, as for spending it is difficult to disentangle the effects of spending shortfalls from discretionary policies. Windfall or shortfall revenues can be notably linked to macroeconomic developments such as financial transactions (property), stock variables (wealth, property) or imports (since, ceteris paribus, an increase in imports does not affect GDP but raises indirect taxes).Footnote 7

As regards external imbalances variables, imports are a tax base for indirect revenues and the import share of GDP can fluctuate substantially. The effect on cyclically-adjusted government revenues of the fluctuation of this tax base that is not closely linked to GDP is represented by channel (ii) and (iii) if this triggers a policy reaction in Fig. 1. Typically, a deteriorating current account balance improves indirect tax revenues, since net capital inflows finance a higher level of domestic absorption (thus imports). Dobrescu and Salman (2011) and Lendvai et al. (2011) highlight the effects of current account movements and positions that are not captured by conventional (even cyclically adjusted) fiscal indicators.Footnote 8 Lendvai et al. (2011) find that the government revenue ratio increases significantly during boom years (i.e. the tax elasticity to GDP is above 1), and look at the effects on revenue components. They find that the revenue ratio increase is primarily driven by indirect taxes (as imports increase more than GDP). The ratio of direct taxes to GDP follows a similar path, but fluctuations are less pronounced. Social contributions are constant as a share of GDP during the boom phase, and tend to increase in the post-boom phase.Footnote 9 Conversely, an increase in exports would generally lead to shortfalls (as a % of GDP), since such increase is reflected in GDP (denominator of the revenue ratio) and since the tax take on exports is generally lower than on other parts of GDP (diminishing the numerator of the revenue ratio).Footnote 10 In addition, external financial flows may also contribute to asset price fluctuations, with government revenue effects as described below.

Variables relevant for internal imbalances include asset prices and financial stock and transaction variables that affect property, wealth and financial transaction taxes. Those tax bases are not directly associated with real GDP developments and may thus affect cyclically-adjusted revenues, triggering revenue windfalls or shortfalls (channel (ii) and (iii) if this triggers a policy reaction in Fig. 1). Liu et al. (2015) provide an overview of the literature on the effects of variables associated with internal imbalances on taxes, noting that most studies focus on housing and equity prices. In particular, asset price booms may not only (temporarily) raise revenues from asset-related taxes, but also lead to generalised revenue growth, due to the wealth effect of increasing asset values on consumption (Eschenbach and Schuknecht 2002,Footnote 11 Eschenbach and Schuknecht 2004 and Girouard and Price 2004). Looking at revenue components, asset price developments seem to affect transaction taxes and corporate taxes, while their effects on direct household taxes and indirect taxes tend to be smaller. The magnitude and nature (contemporaneous or lagged) of the effects differ across countries due to heterogeneity in the respective tax structures, with differences in the size of the tax base related to housing transactions or housing wealth, as well as in the lag structure of taxation (Morris and Schuknecht 2007). The heterogeneity makes empirical estimates challenging.Footnote 12

Price and wage inflation have various effects on public finance indicators. Ceteris paribus, an increase in inflation might have positive consequences for tax revenues (as a % of GDP),Footnote 13 although with opposite effects across tax components and depending on the design of taxes.Footnote 14 Wage increases trigger rises in SSC and PIT ratios to GDP (ceteris paribus), also due to income earners being pushed into higher tax brackets in a progressive tax system. However, wage increases may also adversely affect CIT as production cost rises put pressure on corporate profits. Depending on the extent to which profit margins—and thereby CIT—are squeezed by higher wage costs, the resulting direct effect on windfall revenues could be positive or negative. Any revenue windfalls effects may well be of temporary nature, depending on the degree to which competitiveness is affected by prolonged wage increases above productivity.

Concerning expenditures, the ratio of total government expenditure to GDP tends to decline significantly during the first years of absorption booms (i.e. phases of buoyant domestic demand) but then stabilises, suggesting a shift to a procyclical policy stance (Lendvai et al. 2011). During the early years of the boom, government spending increases in line with its historical trend, and the boom in nominal GDP brings the expenditure ratio down. In the late phase of the absorption boom, the expenditure ratio raises, as nominal spending growth is adjusted upward to match buoyant government revenue. Jaeger and Schuknecht (2007) also find that boom-bust phases tend to exacerbate already existing procyclical policy biases toward higher spending. During a boom phase, revenue windfalls from large asset price increases tend to result in expansionary expenditure policies that erode the positive effects on the budget, due to perceived larger room for discretionary spending. Political-economy factors can accentuate procyclical policy biases further, especially if booms fall in election periods (Buti and van den Noord 2004). Higher inflation also tends to reduce public expenditure ratios in the short run, with potential adverse effects in the longer run.Footnote 15

Methodology to assess the effects of macroeconomic developments on fiscal indicators

We aim at assessing how macroeconomic developments can affect cyclically adjusted fiscal outcomes, based on panel data for the EU Member States. Subsection “Focusing on short-term direct effects on revenues, net of policy measures, and breaking down revenue components, using a novel dataset” presents the conceptual framework and describe how we will focus on the short-term direct effects on revenues, net of policy measures, and then will break down revenue components. Subsection “Type of model and disentangling the direct effect of macroeconomic developments” describes the type of model chosen. Subsection “Selection of the most explanatory variables and model” explains the selection of the most explanatory variables, among a range of possible variables.

Focusing on short-term direct effects on revenues, net of policy measures, and breaking down revenue components, using a novel dataset

First, we focus on government revenues. Empirical studies generally find the weak significance of macroeconomic imbalances on budget balance measures, whether cyclically adjusted or not. By focusing on effects on revenues, rather than budget balance measures, we can distinguish the countervailing effect of discretionary government expenditures increasing (resp. decreasing) when government revenue windfalls (resp. shortfalls) occur. Contrary to government revenues and budget balances, budgetary outcomes for expenditure are subject to government decisions, including decisions not to correct budget overruns.Footnote 16

We use a novel dataset that better identifies the impact of macroeconomic developments on revenues by correcting for the estimated impact of revenue policy measures. The aim is to create windfall revenues that correspond to the direct effects of macroeconomic developments, netting out fiscal policy reactions (both one-offs and permanent) in addition to the business cycle effects. To do so, we adjust the annual cyclically adjusted revenue data for the impact of revenue measures in each Member State using the Commission services database on discretionary tax measures as well as internal estimates of discretionary revenue measures. Endogeneity concerns stemming from the effects of fiscal policy on macroeconomic variables, as discussed by Bénétrix and Lane (2013), are thereby addressed.Footnote 17 Discretionary measures can be potentially large, and are quite heterogeneous across Member States (Fig. 2).

Discretionary revenue measures in the EU (% of GDP). Note: DRM after 2008 are completed with DTM before 2008. If DRM are indicated as zero, they are replaced by DTM (in particular between 2008 and 2010). Source: Own calculations based on AMECO, discretionary tax measure database and internal estimates for discretionary fiscal measures

In addition, the analysis focuses on the short-term direct effects of macroeconomic developments on cyclically adjusted revenues. The complex longer-term developments of macro-variables and their interactions are not part of this study. For instance, a prolonged rise in unit labour costs may trigger an increase in revenues in the short term but could have negative effects through competitiveness losses in the longer term. While we do not capture those dynamics and interactions in the medium and longer term, we do capture their direct impacts on fiscal outcomes at the time they occur, by incorporating dependent variables reflecting these effects. This will allow us in the following part of the study to estimate likely fiscal/revenue impacts of the unwinding of deviations of macroeconomic variables from their assumed equilibrium, even if the actual dynamics are not modelled.

As the current analysis is based on ex-post cyclically adjusted fiscal data, any measurement ‘errors’ of the potential output in real time are not captured. This can lead to underestimation of the effects of macroeconomic variables/developments on cyclically adjusted revenues compared to an analysis using real time data. Indeed, the measurement of cyclically adjusted revenues depends on the measurement of the output gap. Therefore, for a given change in the revenue ratio triggered by a given macroeconomic development, the measurement of the change in cyclically adjusted revenue may depend on whether a change in real GDP is considered a change in either potential output or the output gap. In the years before the 2008–2009 economic and financial crisis, with buoyant economies triggered by imbalances, part of the fluctuations of real GDP had been considered as changes in potential GDP in real time – but then revised ex post as changes in the output gap. The cyclically-adjusted revenues associated with those imbalances would therefore be lower when measured ex post, compared to when they would have been measured in real time, as part of the revenues are assigned ex post to cyclical fluctuations and netted out from cyclically-adjusted revenues.Footnote 18

After looking at the direct effects of macroeconomic developments on aggregate windfall revenues, we estimate the effects on revenue components (personal income tax, corporate income tax, indirect taxes (VAT),Footnote 19 social security contributions and non-tax revenues), all cyclically adjusted, as % of GDP, and corrected from the impact of policy measures. This disaggregation allows a deeper understanding of the effects on revenues, and may underpin the robustness of the findings. Figure 3 illustrates the breakdown considered for the empirical analysis.

Type of model and disentangling the direct effect of macroeconomic developments

We specify dynamic panel regressions, including both country- and year-fixed effects.Footnote 20 The panel approach is more suitable than separate regressions for individual Member States. Indeed, we use annual data for the EU member states, which is the natural frequency to measure fiscal outcomes. Such time series are too short to consider EU Member States one-by-one in separate regressions. At the same time, the European fiscal framework implies the harmonisation of the measurement of fiscal outcomes (notably for the structural balance). It is also likely that it induces some harmonisation of fiscal behaviours, justifying common coefficients among Member States. All these arguments favor the use of a panel approach. In addition, by taking first differences in macroeconomic variables, we avoid some complex issues linked to the identification of equilibrium values for macroeconomic variables, and address issues of fixed effects and non-stationarity of the series.Footnote 21 By considering the lag of the dependent variable as an explanatory variable, we also aim at considering the possibility that the dependent variable is affected by its past level, and possibly not only by macroeconomic developments but also macroeconomic positions.

where wi,c,t are revenue windfalls (shortfalls if negative), \({\delta }_{c}\) and \({\delta }_{t}\) are, respectively, the country- and time-fixed effects, \(\rho\) measures the inherent persistence of our fiscal variables, \(\beta\) is the effect of the changes in macroeconomic variables \({M}_{t}\) and \(\gamma\) is the effect of other explanatory variables \({X}_{t}\). Revenue windfalls is our main variable of interest (Box 1). We also estimate similar models for components of revenue windfalls (shortfalls) and for changes in structural balances. For the structural balance (SB), this gives:

where all variables are expressed in % of GDP.Footnote 22

To disentangle the direct effect of macroeconomic developments on fiscal outcomes from policy decisions, we subtract for the windfall indicators the effect of new measures decided in each of the Member States. Those are reported in the discretionary tax measure database covering the years 2000–2015, and internal estimates of discretionary fiscal measures over 2009–2018. Unlike the former, the latter covers both revenue and expenditure policy decisions. In their overlapping period, they correlate well in a majority of cases,Footnote 23 despite having been documented through two different workflows. The data for both discretionary tax measure and discretionary fiscal measures may be subject to some misclassifications or omissions, and have not been revised ex post on realised outcomes of measures. Considering AMECO data (available as from 2010, and benefitting from ex-post adjustment to effectively implemented measures) instead of the internal estimates of discretionary fiscal measures, does not change the overall results of the study.Footnote 24 Revenues stemming from EU transfers are also subtracted from aggregate public revenues as well as from non-tax revenues.

Selection of the most explanatory variables and model

Overall, our sample covers 28 EU Member States over more than 15 years. Panels are unbalanced but cover on average 22 years per Member State for the structural and cyclically-adjusted variables, 15 years for revenue windfalls.

We confront our fiscal indicators with the macroeconomic variables used in the context of the macroeconomic imbalances procedure, and for completeness, other macroeconomic variables present in the literature.Footnote 25 The broader selection helps ensure that there is no ‘bias’ when screening the variables (i.e. we do not restrict a priori to MIP-variables). As discussed in Sect. “Literature review”, we consider three types of indicators, respectively, linked to external and internal balances, as well as prices (Table 2). Having identified a large set of macroeconomic variables that may potentially affect tax bases, we aim to select a limited number among those variables in our regressions. They may be mutually correlated especially within these categories. To avoid multi-collinearity in our regression, we constrain the model to include one explanatory variable per category.

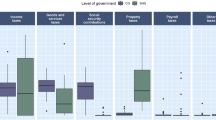

To select variables, we first test the significance of the variables of interest and their combinations, when running a large number of regressions. The results are detailed below and illustrated in Fig. 4.Footnote 26 This analysis also consists of a robustness check for our analysis, showing which variables significance is high and not dependent on model choice.

Visualisation of the estimates and their significance across variables. Note: Keeping the baseline setting (i.e. with Δ.OG and (public debt)t-1 in all regressions) and the variables in two out of the three macroeconomic variable categories unchanged, the various possible explanatory variables of the other category are tested. Coefficients are standardised with the ‘within standard deviation’. The variable indic_housepr represents the growth of housing prices, adjusted by the tax structure: (growth rate of housing price)*(lag of share of property-related taxes in GDP). “d_” indicates first differences of the variable, and “L_” indicates the lag of the variable.

Based on a systematic analysis of all possible regression models with the constraint of having one variable per category, we find that revenue windfalls (shortfalls) are best explained by developments of the following macroeconomic variables as followsFootnote 27:

All external variables considered (trade balance, current account balance, openness, export performance and imports/exports) consistently significantly affect revenue windfalls (shortfalls) (Fig. 4, upper right quadrant). It suggests a robust effect on the tax base and revenues that is not captured by the cyclical adjustment.

Concerning variables related to internal balance, only the household debt and household savings ratios are systematically significant for revenue windfalls (shortfalls), and in some models house prices as well (Fig. 4, lower right quadrant). As discussed in Sect. “Literature review”, less significant effects of financial and asset indicators may be due to heterogeneity in the respective tax structures. When we add an adjusted house price indicator, reflecting the importance of property taxes for the country concerned, we capture effects also on aggregate.Footnote 28

As regards price/competitiveness indicators, the ULC, CPI and terms of trade are sometimes significant for revenue windfalls (shortfalls), and in some cases the GDP deflator as well (Fig. 4, lower left quadrant).

Tests for endogeneity signal no indication of reverse causality between the revenue windfalls (shortfalls) on the left-hand side and explanatory variables. Considering the complex interactions between fiscal variables, fiscal policies and macroeconomic development, studies generally suffer from identification challenges, endogeneity and reverse causality, as for ithe nstance fiscal policy decisions could directly affect trade variables. In particular, fiscal expansion would raise imports directly which in turn would raise taxes and improve fiscal outcomes, leading to biased estimators. Similarly, the output gap and unit labour costs (through public sector wages) could be affected by fiscal policy. This may be less of a concern for our main variable of interest (revenue windfalls/shortfalls) than for the budget balances and expenditure variables, as fiscal policy effects are netted out. The estimation set-up aims to deal with this issue by netting out policy impulses (having revenue windfalls/shortfalls on the left-hand side) and focusing on first differences. The degree to which revenue windfalls (shortfalls) can be expected to affect the considered macroeconomic variables is likely to be minor. This is confirmed by regressions with instrumental variables and adjusting for the Nickell bias as results are not substantially affected.

Based on that analysis, we select the trade balance and household debt as variables for the external and internal categories—in the further analysis. Other variables tested, such as export performance and openness, would also have significant explanatory power. Yet, trade balance and household debt are easier to interpret and are MIP-variables. We also perform some additional statistical tests (multicolinearity and cointegration) to validate this selection.Footnote 29 The results of the regressions are presented in the next section.Footnote 30

Results of the empirical analysis

The resulting estimates for the effects of trade balances and household debt on revenue windfalls (shortfalls) are remarkably robust considering a first differences set-up and important anticipated identification challenges, including differences in national tax systems, the existence of and differences in tax lags (Table 3).

Changes in the trade balance and household debt significantly directly affect revenue windfalls (shortfalls). We find negative effects (significant at the 1% level) on revenues from improvements in the trade balance (Table 3).

Looking also at detailed results for the revenue components (Table 4), we find the following results that are highly significant and consistent with Lendvai et al. (2011):

-

An increasing share of imports to GDP raises indirect taxes. Indeed, higher imports would increase the tax base—while real GDP may not be directly affected. More generally, fluctuations in output composition affect revenue collections by changing the weight of tax-intensive sectors in the economy: a higher reliance on imports leads to higher indirect tax collections, whereas a higher reliance on exports, which are VAT tax exempt, limits tax collections. Developments in trade balance also raise personal income taxes beyond cyclical effects (though to a smaller extent than the effects of indirect taxes). This may be linked to output composition effects: Increasing exports share in GDP may lead to lower direct taxes because the labour share in the export sectors is generally lower than the labour share of production for domestic consumption (with a higher services share) and taxation of capital/corporate profits tends to be lower than labour tax. There may be also specificities of tax systems (some taxes may be recorded as PIT).Footnote 31

-

Similarly, we find positive effects (significant at the 1% level) of household debt on revenues (Table 3), reflecting the mechanisms by which credit growth expands the tax base beyond GDP growth with an increase in asset values, financial transactions and (import) demand, which is consistent with Eschenbach and Schuknecht (2004).

-

Like the trade balance, household debt contributes to revenue windfalls through increases in personal income taxes and indirect taxes (Table 4). First, changes in the valuation of assets and volume of transactions are not directly reflected in real GDP developments but are affecting indirect taxes. Wealth and capital gains taxes can benefit from rising household wealth from e.g. stock and real estate markets that move in line with household debt. Asset price developments (associated with household debt) may also affect direct household taxes in a more indirect manner: if realised capital gains are taxed in corporations they may be taxed again at the household level; small, unlisted companies may pay taxes on their capital gains if the building or stocks owned by the company are sold (revalued) and taxes are then paid on the personal account of the owner.Footnote 32

There are some further interesting findings when we compare the measured effects on the structural balance with those of the revenue windfalls (shortfalls).

Changes in the output gap significantly affect the structural balance, which corroborates the existence of procyclical discretionary policies. The measured effect of the change in output gap on the structural balance is negative and highly significant, consistent with procyclical spending or revenue policy. This procyclical policy effect is, however, much lower when the revenue windfalls (shortfalls) are considered as left-hand side variables, as (procyclical) revenue policy effects are removed. Some effect of the output gap remains at least in the LSDV regression for revenue windfalls (shortfalls). This may be due to the procyclical nature of the potential output measure that affects the calculation of windfall revenues.Footnote 33 In addition, consistent with the findings that the structural balance is much more affected by policy variables than revenue windfalls (shortfalls), the explanatory variables that affect the policy response significantly affect the structural balance but not revenue windfalls (shortfalls) (Table 3). In particular, the dummies for election years and overachievement of the medium-term budgetary objective as well as the level of debt affect the structural balance but not the revenue windfalls (shortfalls).

Offsetting policy measures are the likely reason for the lack of significant direct effects of macroeconomic developments on the structural balance (Table 3). This lack of significance is in line with findings in the literature (Bénétrix and Lane 2013). Revenue windfalls may have been used for discretionary expenditure increases and revenue-reducing measures in boom years. Regressions with cyclically adjusted revenue and expenditure as dependent variables components confirm that there are counteracting effects explaining the aggregate results (not shown). The coefficients for cyclically adjusted revenue and expenditure have the same sign and thus may cancel out the effect on the budget balance, except for the change in the output gap.

Implications for fiscal outcomes

As demonstrated above, fiscal outcomes are affected by fluctuations in macroeconomic and financial indicators beyond GDP and the economic cycle. This means that macroeconomic and financial developments potentially trigger (or mitigate) fiscal risks that are not fully considered in the cyclically-adjusted fiscal indicators. Taking into account the revenue effects of macroeconomic developments could help better assess the underlying budgetary position, fiscal risks and fiscal efforts to improve debt sustainability.

Based on the regressions above, we illustrate, for every country in the panel, the potential impact over time of macroeconomic developments on the measured fiscal efforts (subsection “Effects of macroeconomic and financial developments on fiscal effort”). This helps better understand the underlying fiscal efforts, since the revenue windfalls (shortfalls) triggered by macroeconomic developments affect the fiscal effort, whereas they are not directly linked to fiscal measures undertaken. We also illustrate the potential impact of the deviation of macroeconomic variables from their assumed ‘equilibrium’ on fiscal positions (subsection “Effects of macroeconomic and financial deviations from equilibria on the government budget balance”). This helps better understand the underlying budgetary positions and fiscal risks since reversal of macroeconomic variables to their equilibrium values would trigger revenue windfalls (shortfalls).

It should be noted that the country-specific results shown in this section should be considered indicative. National tax systems have many country-specificities that may not be reflected in a panel analysis since tax bases, rates and lags differ. As a result, the impacts of macroeconomic developments may differ substantially. Yet, this methodology requires panel data, and due to data limitations, we cannot estimate the country-specific impact coefficients. We, therefore, rely on common impact coefficients across EU Member States. Tests for a range of country groupings (not shown in this paper) find that the coefficients reflecting the revenue impacts of macroeconomic developments are relatively similar across the range of different country groupings. Finally, estimating the potential revenue effects of a reversal of macroeconomic variables to their ‘equilibrium’ levels requires assumptions on the latter, which are uncertain.

Effects of macroeconomic and financial developments on fiscal effort

Macroeconomic developments affect Member States’ fiscal effort as measured by the yearly change in the structural balance, through revenue windfalls (shortfalls). According to the EU fiscal rules, Member States target a fiscal effort measured in terms of cyclically-adjusted balance corrected for one-off measures. However, the ex-post attainment of the required fiscal effort may be affected by direct revenue effects of macroeconomic developments that affect tax bases that are not directly reflected in real GDP, such as changes in imports and household debt (also as a proxy for property prices and transactions). For instance, at any given amount of fiscal measures undertaken by governments, if the imports decrease, the resulting revenue shortfalls adversely affect the ex-post measured fiscal effort. In general, any increase in revenue windfalls (shortfalls) related to yearly macroeconomic developments improves (worsens) the ex-post measured fiscal effort, independent of the fiscal measures undertaken.

The effect of macroeconomic developments on the measured fiscal effort is estimated based on the analysis of the previous section. This effect corresponds to the (additional) revenue windfalls (or shortfalls) stemming from yearly macroeconomic developments (compared to the previous year). To estimate it, we consider the macroeconomic variables whose developments have the most significant and consistent effects on windfall revenues (i.e. trade balance and household debt) and the associated coefficients β that reflect those effects (Table 3, column 1, i.e. a coefficient of -0.139 for the trade balance, and 0.0704 for the household debt).Footnote 34 Compared to the previous year, the additional revenue windfalls (shortfalls) estimated to have been triggered by developments in trade balance and households debt write:

where \(\Delta {TB}_{t}\) and \(\Delta {HHDebt}_{t}\) are the yearly differences in trade balance and household debt.

Over the two past decades, this estimated effect has been significant in many EU Member States. The ‘underlying fiscal effort’ (i.e. adjusted for the revenue windfalls/shortfalls related to macroeconomic developments) can be significantly different from the fiscal effort measured in the surveillance process. Figure 5 breaks down the effects of yearly developments in trade balance and household debt on the fiscal effort, over the past two decades. The y-axis is reversed to facilitate the reading in terms of fiscal effort: positive values here signal increasing shortfall (or decreasing windfall) revenues, indicating that the underlying fiscal effort (i.e. adjusted for the revenue effects of revenue windfalls/shortfalls related to macroeconomic developments) is higher than apparent. Results show that effects on fiscal effort come more from developments in trade balance than in household debt and that they can be significant. For instance, for Italy, in 2012–2015, macroeconomic developments consistently contributed to sizable revenue shortfalls. Our estimates suggest that the underlying fiscal effort was substantially higher than the fiscal effort measured in the surveillance process, by more than 0.4 pps. (0.3 pps.) of GDP in 2012 (2013). For Germany, for most years since 2000, the underlying fiscal effort would have been also consistently higher than the fiscal effort measured in the surveillance process, regularly by more than 0.2 pps. of GDP.

Revenue windfalls/shortfalls associated with yearly developments in trade balance and household debt (EU + UK, without Luxemburg and Cyprus, % of GDP, reversed y-axis). Note: In total, positive values indicate increasing shortfall (or decreasing windfall) revenues triggered by macroeconomic developments, that adversely affect the fiscal effort to improve debt sustainability measured in terms of cyclically adjusted balance. The underlying fiscal effort (adjusted for changes in macroeconomic imbalances) is then higher than the fiscal effort measured in terms of cyclically adjusted balance. Conversely, negative values indicate increasing windfall (or decreasing shortfall) revenues: the underlying fiscal effort (adjusted for macroeconomic developments) is then lower than the fiscal effort measured in terms of cyclically adjusted balance. The contributions to changes in windfall/shortfall revenues can be broken down: -contribution to the trade balance developments -contribution of the household debt developments. Luxembourg and Cyprus are not shown due to data issues

Conversely, for most years since 2000, macroeconomic developments in France implied that the underlying fiscal effort to improve debt sustainability was in fact lower than the fiscal effort measured in the surveillance process.Footnote 35

These findings suggest that considering macroeconomic developments such as changes in the trade balance and household debt would contribute to a better understanding of the underlying fiscal effort. When analysing the yearly change in structural budget balance, considering the revenue windfalls and shortfalls associated with macroeconomic developments allows for better assessing fiscal effort ex post. For instance, in a context of an improving trade balance, the actual fiscal effort might be significantly larger than the one measured by the change in the cyclically adjusted or structural balance.

Effects of macroeconomic and financial deviations from equilibria on the government budget balance

To illustrate the relevance of macroeconomic developments for budget balance developments, we estimate revenue windfalls/shortfalls related to deviations of macroeconomic variables from estimated ‘equilibria’ or norms. Similar to the subsection above, we consider the macroeconomic variables whose developments have the most significant and consistent effects on windfall revenues (i.e. trade balance and household debt) and the associated coefficients β that reflect those effects.Footnote 36 In addition, correcting for the fiscal effects of deviations from macroeconomic variables requires defining equilibrium levels for each macroeconomic variable used. To do so, we consider proxies for equilibrium levels of the macroeconomic variables of interest estimated in the context of the EU Macroeconomic Imbalances Procedure, based on the academic literature.Footnote 37 The deviations of macroeconomic variables from their norms can be considered as gaps (thereafter ‘XGAPS’, similar to the output gap that reflects a deviation of GDP from its ‘equilibrium’ level) which, if corrected, trigger fiscal effects. Those potential fiscal effects write:

while the underlying revenue windfalls estimated to have been triggered by deviations of macroeconomic variables from their norms write:

where \({TBGAP}_{t},\) and \({\mathrm{HHDebt}GAP}_{t}\) are the gaps in resp. trade balance and household debt.

For instance, in a Member State with a trade balance below its norm, a reduction in the gap in trade balance (e.g. via lower imports) would be a likely future development. It would ceteris paribus reduce revenue windfalls. The ‘underlying cyclically adjusted fiscal position’ (i.e. the CAB adjusted for the potential revenue effects of a reversal of trade balance and household debt to their norms) is then worse than what the CAB may suggest. Figure 6 illustrates those potential effects by Member State and breaks down the effects of developments in trade balance and household debt.

Revenue windfalls (shortfalls) related to deviations of trade balance and household debt from their equilibria (EU + UK, without Luxembourg and Cyprus, % of GDP). Note: In total, positive values indicate windfall revenues triggered by macroeconomic imbalances: for positive values, the ‘underlying balance’ is worse (lower) than the CAB indicates, as the former nets out these windfalls. Conversely, negative values indicate revenue shortfalls triggered by macroeconomic imbalances. The underlying the fiscal position may in fact be better than the one measured by the CAB, as the former nets outs these shortfalls. The contributions to windfall/shortfall revenues can be broken down as follows: Contribution to windfall/shortfall revenues of the trade balance. Contribution to windfall/shortfall revenues of household debt. These contributions depend on the norms (equilibria) for trade balance and household debt. Coefficients to calculate the revenue windfalls (shortfalls) are based on EU averages and do not take account of an individual country’s tax system. Luxembourg and Cyprus are not included due to data issues

Conclusions

Macroeconomic imbalances and developments substantially and directly affect budgetary indicators and fiscal outcomes. Considering the first-differences set-up and the different tax lags across countries, the empirical findings are remarkably robust. Developments in macroeconomic variables—particularly the trade balance, current account and household debt—significantly affect cyclically adjusted government revenues. A deteriorating trade balance, or rising household debt, for instance, triggers direct windfall revenues, mainly due to increased tax bases beyond GDP. This mechanically improves the budget balance indicators, even if these are adjusted for cyclical effects.

Cyclically-adjusted budget balance indicators are central elements in EU countries’ budgetary frameworks and in the EU fiscal framework. The results in this paper suggest that systematically considering the effects of macroeconomic developments on government revenues would improve understanding of the developments in budget indicators and debt sustainability. The findings also support the emerging consensus on relying more on government expenditure-based measures to assess compliance with fiscal rules rather than budget balance rules. Recently, the European Commission has emphasised the use of expenditure indicators in budgetary surveillance, which helps to identify whether government expenditure developments are in line with underlying economic activity over the longer run.

As the focus on medium-term fiscal plans has increased, these plans should also consider the impact of macroeconomic developments and imbalances on the underlying fiscal position and debt sustainability. They should anticipate a possible reversal of those macroeconomic imbalances to their ‘equilibrium’ levels that can trigger sizable revenue windfalls (shortfalls), events in the wake of the 2008 crisis has shown.

Further work could help to better gauge the underlying budgetary position and inform medium-term budgetary planning and debt sustainability analysis. Measurement of the direct impact of macroeconomic variables on fiscal outcomes may benefit from further work (i) at the country level, assessing in detail country tax structures and lags, to identify how macroeconomic developments are related to tax bases that are not directly linked to GDP; and (ii) on equilibrium levels for the macroeconomic variables relevant for revenue windfalls (shortfalls).

Data availability

The analysis in this article uses a discretionary tax measure database covering the years 2000–2015, as well as estimates of discretionary fiscal measures that are internal to the European Commission over 2009–2018. The latter internal estimates can be provided on an aggregate basis upon request. (In addition, considering AMECO data (available as from 2010) instead of these internal estimates of discretionary fiscal measures, does not change the overall results of the study.)

Notes

Graph A.1. in the Annex shows the occurrence of (unexpected) windfall revenues over time in Member States.

In addition, macroeconomic imbalances may also substantially affect potential output, in terms of both level and composition (through sectoral reallocations, over- or under-investment and hysteresis effects), as well as potential output measurement leading to ex-post potential output revisions. Both indirectly affect cyclically-adjusted fiscal indicators.

While cyclically-adjusted budget balance indicators, such as the cyclically adjusted budget balance (CAB) and the structural balance (SB), are central elements in EU countries’ budgetary frameworks and in the EU fiscal framework, the fiscal effects of macroeconomic developments that go beyond cyclical effects are not explicitly and comprehensively considered.

Morris and Schuknecht (2007) note that the impact of discretionary tax changes makes it extremely difficult to estimate budget elasticities (to changes in asset prices) in a reliable way using econometric estimation. They suggest that ideally, these effects should be netted out, but notes that no such estimates of the revenue impacts of policy changes were available in a consistent data series across countries and time.

The term ‘deviations’ refers to gaps relative from estimated norms or equilibria usually defined. It does not necessarily reflect a situation of ‘macroeconomic imbalance’ in the sense of the MIP procedure, i.e. ‘trends giving rise to macroeconomic developments which are adversely affecting, or have the potential adversely to affect, the proper functioning of the economy of a Member State or of the economic and monetary union, or of the Union as a whole’.

Note that the ‘twin-deficit hypothesis’ literature on external and fiscal imbalances is beyond the scope of this study. As explained by e.g. Corsetti and Mueller (2006) and Afonso et al. (2018), the twin-deficit hypothesis suggests that the government and current account balance move in the same direction. Chinn and Ito (2019) also suggest a causal link going from fiscal tightening to external surpluses, consistent with a ‘twin-surplus hypothesis’. The effect that this paper aims to capture goes in the opposite direction, with revenues improving as the current account balance deteriorates. section “Methodology to assess the effects of macroeconomic developments on fiscal indicators” discusses how endogeneity concerns that may arise from this hypothesis are addressed.

Such as customs duty, excise duty, anti-dumping duty and value added tax.

Lendvai et al. (2011) adjust cyclically adjusted balances for absorption booms and show that standard approaches used to adjust budget balances for the cycle could miss part of the temporary revenues accruing during absorption booms when the current account deteriorates sharply.

Note that a breakdown of trade balances in exports and imports may provide additional information on drivers of tax windfalls, because imports and exports are not equally tax-rich. Therefore, a constant trade balance with different levels of imports and exports can have different fiscal effects via different budgetary elasticities.

An exception is revenues derived from exports of government-owned resources, on which the revenues may be higher than on the other parts of GDP. In this case, exports may lead to windfalls.

Liu et al. (2015) incorporate the impact of asset price cycles in the calculation of structural fiscal balances.

See also Claessens et al. (2011), Bénétrix and Lane (2013). Credit growth and household debt indicators are relatively easily comparable across countries and highly correlated to house prices and equity prices, and so can consist of good proxies for internal imbalances variables. Bénétrix and Lane (2015) show how fiscal variables co-vary with the financial cycle, which they capture by the credit growth and current account balance.

Heinemann (2001), based on an econometric panel analysis on a sample of OECD countries over 1972–1996.

With progressive income tax and an imperfect indexation of brackets, for instance, inflation increases real tax revenues, at policy unchanged (Oates 1988). However, inflation may reduce real tax revenues for taxes with considerable lag between the taxable event and the moment the tax is paid (Olivera 1967, Tanzi 1977). Alesina and Perotti (1995) find that inflation tends to have positive effects on individual income taxes and social security contributions, and negative effects for corporate income taxation. In addition, inflation is expected to be neutral for proportional taxes without a significant collection lag, such as VAT. For social security contributions, two opposite effects are at play: as social security contributions are often paid as a flat rate of income up to a maximum value, inflation may dampen government revenues by reducing the real levels.

With imperfect indexation of eligibility for means-tested benefits (and of their level), inflation automatically decreases expenditure ratios. In addition, government expenditure limits are often set in nominal terms, so higher-than-expected inflation may decrease spending in real terms, absent discretionary measures. However, in the long run, private sector wage increases affect public sector wages with a lag, at least in OECD countries (Fernández-de-Córdoba et al. 2012), possibly triggering increases in public expenditure. During booms, governments expand employment and wages, while in downturns, lack of tax revenues can force the government to cut back the wage bill – the latter occurring with rigidities (Afonso and Gomes 2014).

It is also more difficult to make a distinction between policy and macroeconomic effects for expenditures, partly due to data availability. Discretionary tax measure and discretionary fiscal measure databases cover the years 2000–2015 and 2009–2018, respectively. Unlike the former, the latter covers both revenue and expenditure policy decisions.

Endogeneity concerns should be seen in the context of the ‘twin-deficit hypothesis’ that suggests that a larger fiscal deficit, through its effect on national saving, leads to an expanded current account deficit. If the twin-deficit hypothesis holds, both budget balance and current account balance (or trade balance) would be jointly determined and move in the same direction. The tax elasticity effect that we investigate, on the contrary, suggests that the budget deficit improves as the current account deteriorates. By netting out the effect of government expenditure and of discretionary revenue policy measures from our LHS variable of interest, the potential for endogenous effects is much reduced when compared to studies in the literature. What remains is the disposable income effect of windfall revenues which stem from e.g. the tax take on increased consumption of imports. This effect is of secondary order but may imply minor endogeneity issues. Correcting for Nickel bias and applying instrumental variables estimates confirm that these effects are minor in our setting.

Throughout the text, tables and graphs indirect taxes are referred to as VAT.

Econometric tests show that year-fixed effects are always jointly significantly different from zero. Autocorrelation of the explained variable is not always significantly different from zero but is kept throughout for consistency. Country-fixed effects might be discarded, as our explained variable is a first difference, unless we take account of heterogeneous long-term trends across countries. However, our LSDV estimators control for them, as the LSDV corrects for the Nickell bias, following Kiviet (1995) and Bruno (2005).

Unit root tests suggest that, while independent and explanatory variables are not stationary in levels, their first differences are.

Potential GDP for the change in structural balance.

Correlation is above 60% for more than 80% of the Member States on aggregate and above 64% of the cases by revenue components.

Another source for DRM from 2010 is the AMECO database. To use it, AMECO data from 2010 is merged with the data of the discretionary tax measure database before 2010. When using AMECO data from 2010, the discretionary fiscal measure database shares are used for the revenue breakdowns into components. Using AMECO data does not change the overall results, and the results shown are those using the discretionary tax measure and discretionary fiscal measure databases.

Standard baseline explanatory variables of the fiscal reaction functions indicator are also included in the regression model but a priori not expected to affect windfall revenues. As a baseline, we consider the usual explanatory variables in this literature, including political economy ones (election years), the economic cycle, population structure and ageing, budget constraints (debt level, interest rate, EDP procedure, fiscal objectives achievement). The political economy variables are relevant for fiscal outcomes that can be affected by policy. While these variables would not be expected to affect windfall revenues, they can be expected to affect budget balance variables or expenditures, or possibly revenue variables that have not been adjusted for discretionary policy measures.

In addition to the data shown, we performed less systematic tests for a wider set of macroeconomic variables.

A Bayesian model averaging test including all macroeconomic variables of interest and running all possible regression models also confirms the results.

We add the following adjusted house price indicator: (real house price)*(share of property related taxes in GDP), taken from Taxation Trends in the European Union, 2019 edition, DG TAXUD, European Commission.

In the main analysis below, we exclude unit labour costs and focus the analysis on trade balance and household debt, also because of correlation of unit labour costs and other price variables with nominal GDP which is the denominator of all other variables. However, we show the results of the regressions in the Annex when considering the trade balance, household debt and nominal unit labour costs as the variable for each of the three categories of macroeconomic variables – i.e. those associated with external balance, internal balance and price/competitiveness.

The analysis also shows that for the macroeconomic variables linked to external imbalances, the change in the current account balance is a strong alternative explanatory variable (instead of the trade balance). The full analysis has been performed also with the current balance results. Similar outcomes are obtained as with the trade balance. The results are not shown here.

In addition, there could be some measurement issues (for discretionary measures or output gap).

Morris and Schuknecht (2007).

Note that calculation of the expenditure benchmark in the EU fiscal framework is based on a long-term average of potential output and thus addresses effects of some procyclicality of the potential output measure.

We consider the same \(\beta\) for all countries, based on a panel regression with all EU countries. Tests by country group suggest that, while there are some differences between Member States, the coefficients may be close for most countries.

Here as well, some caveats remain, notably as the coefficients β to estimate the effect of macroeconomic developments on fiscal effort are based on a panel regression, thus do not consider country specificities. Robustness test with estimates for country groups (not shown), however, confirm that findings are robust. The ‘underlying fiscal effort’ (adjusted for the effects of macroeconomic developments) also does not rely on the definition of norms/equilibria for macroeconomic variables that are used in the next subsection to estimate the effects of macroeconomic developments on cyclically adjusted fiscal positions.

We consider the same \(\beta\) for all countries, based on a panel regression with all EU countries. Tests by country group suggest that, while there are some differences between Member States, the coefficients may be close for most countries.

For the trade balance norm, we consider the required trade balance to stabilise the NIIP over 10 years. This norm is consistent with what is used in the Alert Mechanism Report of the European Commission in the context of the MIP surveillance, as well as with the external balance assessment methodology of the IMF. For the household debt norm, we consider fundamentals-based benchmarks that are used by the European Commission when assessing macroeconomic situations of Member States. They are derived from regressions capturing the main determinants of credit growth and taking into account a given initial stock of debt.

References

Afonso A, Gomes P (2014) Interactions between private and public sector wages. J Macroecon 39:97–112

Afonso A, Huart F, Jalles J, Stanek P (2018) Twin deficits revisited: a role for fiscal institutions? REM working paper, 031–2018

Alesina A, Perotti R (1995) The political economy of budget deficits. IMF Staff Pap 42(1):1–31

Bénétrix A, Lane P (2013) Fiscal cyclicality and EMU. J Int Money Financ 34:164–176

Bénétrix A, Lane P (2015) Financial cycles and fiscal cycles. Department of Economics, Trinity College. In this paper, we show that fiscal variables also co-vary with the financial cycle, as captured by fluctuations in the current account balance and credit growth

Borio C, Disyatat P, Juselius M (2014) A Parsimonious approach to incorporating economic information in measures of potential output. BIS Working Paper No. 442

Borio C, Disyatat P, Juselius M (2016) Rethinking potential output: embedding information about the financial cycle. Oxf Econ Pap 69(3):655–677

Bruno G (2005) Approximating the bias of the LSDV estimator for dynamic unbalanced panel data models. Econ Lett 87(3):361–366

Buti M, van den Noord P (2004) Fiscal policy in EMU: rules, discretion and political incentives. European Economy. Economic Papers 206

Chinn M, Ito H (2019) A requiem for ‘blame it on Beijing’: interpreting rotating global current account surpluses. NBER working paper No. 26226

Claessens S, Kose M, Terrones M (2011) Financial cycles: what? how? when? Int Semin Macroecon 7(1):303–344

Corsetti G, Müller G (2006) Twin deficits: Squaring theory, evidence and common sense. Econ Policy 21(48):597–638

De Agostini P, Paulus P, Tasseva I (2016) The effect of changes in tax-benefit policies on the income distribution in 2008–2015. Research note 02/2015, study for European Commission, DG EMPL

Dobrescu M, Salman M (2011) Fiscal policy during absorption cycles. IMF Working Paper No. 11–41

Eschenbach F, Schuknecht L (2004) Budgetary risks from real estate and stock markets. Econ Policy 19(39):314–346

Fernández-de-Córdoba G, Pérez J, Torres J (2012) Public and private sector wages interactions in a general equilibrium model. Public Choice 150(1–2):309–326

Girouard N, Price R (2004) Asset price cycles, ‘one-off’ factors and structural budget balances. OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 391

Heinemann F (2001) After the death of inflation: will fiscal drag survive? Fisc Stud 22(4):527–546

Jaeger A, Schuknecht L (2007) Boom-bust phases in asset prices and fiscal policy behavior. Emerg Mark Financ Trade 43(6):45–66

Kiviet J (1995) On bias, inconsistency, and efficiency of various estimators in dynamic panel data models. J Econ 68(1):53–78

Lendvai J, Moulin L, Turrini A (2011) From CAB to CAAB? Correcting indicators of structural fiscal positions for current account imbalances. European Economy—Economic Paper No. 442. Directorate General Economic and Financial Affairs (DG ECFIN), European Commission

Liu M, Mattina T, Poghosyan T (2015) Correcting ‘beyond the cycle’: accounting for asset prices in structural fiscal balances. No. 15–109. International Monetary Fund

Morris R, Schuknecht L (2007) Structural balances and revenue windfalls: the role of asset prices revisited. ECB Working Paper No. 737

Mourre G, Poissonnier A, Lausegger M (2019) The semi-elasticities underlying the cyclically-adjusted budget balance: an update and further analysis. Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs Discussion Paper 098

Oates W (1988) On the nature and measurement of fiscal illusion: a survey. In: Brennan G, Grewal B, Groenewegen P (eds) Taxation and fiscal federalism: essays in honour of russel mathews. Australien National University Press, Canberra, pp 65–82

Olivera J (1967) Money, prices and fiscal lags: a note on the dynamics of inflation. PSL Quart Rev 20:82

Osbat C, Jochem A, Özyurt S, Tello P, Bragoudakis Z, Micallef B, Sideris D, Papadopoulou N, Ajevskis V, Krekó J, Gaulier G (2012) Competitiveness and external imbalances within the euro area. ECB Occasional Paper Series No. 139

Pierluigi B, Sondermann D (2018) Macroeconomic imbalances in the euro area: where do we stand? ECB Occasional Paper No. 211

Schuknecht L, Eschenbach F (2002) Asset prices and fiscal balances. ECB Working Paper No. 141

Tanzi V (1977) Inflation, lags in collection, and the real value of tax revenue. IMF Staff Pap 24(1):154–167

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. This article has been written when the authors were working at the European Commission (DG ECFIN). No other funding has been received to assist with the preparation of the manuscript.

Research involving Human Participants and/or Animals; informed consent

This research did not involve Human Participants and/or Animals.

Permissions

A previous version of this article has been included in a non-academic publication: European Commission, 2020. Public finances in EMU, Report on Public Finances in EMU 2019, Institutional Paper 133, July, 105–132. It is permitted to include figures, tables and text passages already published, for both the print and online formats. The contribution, including figures, tables, or text passages is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Additional information

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily represent the views of the European Commission, the University of Paris Nanterre, or the INSEE. We would like to thank A. Cepparulo, K. Leib, P. Lescrauwaet, P. Mohl, G. Mourre, L. Pench, L. Piana, V. Reitano, and A. Turrini for their precious comments and suggestions.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Langedijk, S., Poissonnier, A. & Turkisch, E. The impact of macroeconomic developments and imbalances on fiscal outcomes. SN Bus Econ 3, 105 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-023-00466-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-023-00466-9