Abstract

Morocco is a multilingual nation where language policy debates have been going on since independence. In recent years, the Tamazight language (TM) has been the subject of one of the most contentious debates in this country. To understand the dynamics of this debate, the present study scrutinises the discursive construction of the TM in news media discourse. Specifically, it maps the language ideologies (LIs) circulated in meta-linguistic discourse(s) about TM and shows how they are discursively constructed and disseminated in news media. The paper argues that LIs effectively shape and orient language policy debates. Benefiting from the methodological synergy that the combination of corpus linguistics (CL) and critical discourse analysis (CDA) offers, the study analyses a corpus of 658 newspaper articles (803.444 tokens). Statistical measures such as absolute and relative frequency, collocates analysis and concordance analysis are the major CL tools used for the quantitative analysis of the data. On the other hand, the study uses CDA analytic tools developed within CDA variety Discourse-Historical Analysis (DHA), namely discursive strategies, the analysis of argumentation schemes and topoi. The analysis revealed that discourses of historicity, homogeneity, modernity, ‘scientificity’ and victimhood are some of the major discourses disseminated in the ideological debate about the situation of Tamazight in Morocco. The study offers some methodological implications for the marriage between CL and CDA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Morocco is a multicultural and multilingual nation. Throughout its history, different cultures, ethnicities and languages came into contact on its land, resulting in a complex sociolinguistic situation. A good number of languages and local dialects make up the linguistic landscape of the country, namely Standard Arabic (SA), Moroccan Arabic (Darija) (90.9%),Footnote 1 Hassania (0.8%), Standard Tamazight (ST) along with locally spoken Berber varieties such as Tashelhit (14.1%), TamazightFootnote 2 (7.9%) and Tarifit (4%) (HCP 2014), colonial languages particularly French and Spanish, and lastly English considered a ‘neutral’ global language that is gradually gaining ground. The intense interaction of all these language varieties for years has created a very rich and yet complex sociolinguistic landscape in the country. SA and ST are the only two constitutionally official languages, however, French, as a de facto official language, is also widely used in public administration and some key sectors like health, economy, military and education.

Amid this wide and diverse linguistic market, the relationship between languages is by no means symmetrical. While some varieties enjoy a higher status thanks to the social functions they serve (e.g. SA and French), other varieties are either marginalized (e.g. MA and Berber varieties) (Boukous 2005) or still struggling to gain true recognition (e.g., ST). Tamazight (henceforth TM), the focus of this study, was officialised in 2011 after a new constitution was adopted following what was then called the ‘Arab Spring’. Nonetheless, the debate about the officiality of TM was instigated well before 2011. In 1991, becoming aware of TM as a ‘crucible’ that can unify the then-fragmented Amazigh Cultural Movement,Footnote 3 several Amazigh associations drafted the ‘Agadir Charter for Linguistic and Cultural Rights’, in which they made demands for the promotion of Amazigh culture and language. Specifically, they called for the standardisation and integration of TM into the Moroccan educational system. This Charter marked the real beginning of an Amazigh movement and the emergence of a new discourse around TM based on historicity claims and human rights philosophy, particularly linguistic rights.

These demands for the promotion of the Amazigh language and culture gained greater momentum after King Hassan II encouraged the teaching of local dialects in public schools in his 1994 speech.Footnote 4 This speech was “the real turning point in the official attitude toward Amazigh” (Sadiqi 2011, p. 35). It was, however, the ascension of Mohammed VI to the throne in 1999 that paved the way for the concretization of what was a few years ago only an Amazigh dream. The King’s throne speech in 2001 and his catalytic Ajdir speech in the same year accentuated the extreme necessity to promote the Amazigh language and culture. To achieve this goal, the King declared the establishment of the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture (IRCAM) and in 2003, TM was introduced into the educational system. Eight years later and amid the turbulent situation several Arab countries were undergoing following the 2011 revolutions, TM became an official language alongside Arabic in Morocco’s new Constitution.

For more than three decades now, TM has been the subject of an ongoing contentious debate between opponents and proponents (e.g. Islamists and secular Amazigh activists), amidst Amazigh activists themselves, politicians, and linguists. More often than not, the debate transformed into a bitter ideological debate between parties each marshalling a set of language ideologies to advance its case. Discourses of historicity, human rights, secularization, national identity, dissent, etc., shaped the way the Tamazight language is debated and discursively represented.

Integrating corpus linguistics and critical discourse analysis methodologies, this paper investigates the language ideologies circulated about TM in media discourse. In particular, it looks at how this ‘variety’ is discursively constructed in the ongoing language policy debate disseminated in an electronic newspaper. Accordingly, the study seeks to answer two closely interrelated questions:

-

How is the Tamazight language discursively constructed in media discourse(s)? and

-

What language ideologies are circulated about it in the language policy debate in Morocco?

Theoretical and conceptual background

The present paper is a sociolinguistic study that looks at the debate instigated by language policy decisions concerning the Tamazight language in Morocco and seeks to reveal the discursive representations of this variety in the media. To that end, the paper draws on two theoretically ‘distinct’ and ‘relatively new’ traditions within linguistics (Baker et al. 2008, p. 274), namely CL and CDA. The trend of combining a set of synergetic analytical tools offered by both approaches has proven to be methodologically powerful and qualitatively fruitful (Baker and McEnery 2015). Both CL And CDA have been used in sociolinguistic research. For instance, CL has been used to study diachronic and synchronic linguistic variation and change (Baker 2010), while CDA has been widely used, inter alia, to analyse linguistic practices and the associated language ideologies and discourses.

Corpus linguistics

Corpus linguistics (CL) is a branch of linguistics that studies and analyses linguistic corpora (pl. of corpus). A corpus is “a ‘body’ of language, or more specifically, a (usually) very large collection of naturally occurring language, stored as computer files” (Baker 2010, p. 6). So, a corpus analyst normally needs first to amass a huge sample of linguistic data according to some specific criteria and, second needs to use computer programs to aid the exploration and analysis of the data. CL has been defined as “the study of language based on examples of real-life language use’ (McEnery and Wilson 1996: 1, cited in Baker 2006, 2010). Alternatively, it is defined as “a collection of tools and techniques for linguistic analysis” (Partington et al. 2013, p. 7).

There is a lively controversy in the literature over how best to characterize CL. On the one hand, according to Taylor (2008), some researchers such as Leech (1992), Stubbs (1993) and Teubert (2005) prefer to construe CL as a new paradigm or a theoretical or even a philosophical approach to the study of language. On the other hand, other practitioners (Baker and McEnery 2015; Thompson and Hunston 2006; McEnery and Hardie 2012; Partington et al. 2013) prefer to see CL as a methodology (For a full account of the different characterizations of CL in the literature, the reader is referred to Taylor 2008). For this paper, CL is viewed and used as a methodology for linguistic and textual analysis. It is used in combination with CDA tools to help, especially with the quantitative dimension of the critical analysis of the corpus.

The most distinctive feature of CL is the use of several frequency-based techniques to analyse a large amount of linguistic data with the aid of software specifically designed for this purpose. It has never been so easy to undertake such a task, and this is exactly what makes CL a very “powerful methodology” (Baker and McEnery 2015, p. 1). One of the most used techniques in CL is the analysis of ‘keyness’. To find ‘keywords’, a comparison is drawn between two corpora, the corpus of interest and another ‘reference’ corpus. Functionally, Keywords help “identify salient themes” in corpora and “serve as indicators of expression and style as well as content (Hunt and Harvey 2015, p. 139). More importantly, especially for discourse-oriented analysts, keyness analysis can “help reveal the presence of discourse” (Baker 2006, p. 121).

Collocates analysis is another powerful technique in CL. The focus of this type of linguistic analysis is on the most frequent collocations. Collocates are words that exhibit a statistically significant tendency to co-occur in close proximity usually within a span of five tokens on each side of the search term. Thus, according to Baker (2006, p. 96), “the phenomena of certain words frequently occurring next to or near each other is collocation”. In addition to their role in “understanding meanings” (Baker 2006, p. 96), the analysis of collocates can uncover ideological constructions and representations in texts by interrogating the relationship between collocating words. This relationship usually becomes “reified and unquestioned” due to the high frequency of use of a particular collocation (Stubbs 1996: 195, cited in Baker and McEnery 2015, p. 2).

Another yet extremely useful tool in CL is concordance analysis (KWIC). The technique entails a close look at concordance lines to see how a query term is used in context (context size is usually 10 tokens). According to McEnery and Hardie (2012, p. 1), concordancing is a “well-established” procedure and it is “central” to CL. The scrutiny of concordances permits an insightful qualitative analysis of the discourse(s) present in a corpus. Other tools and techniques that a corpus analyst can find helpful in conducting a linguistic analysis of a dataset are dispersion, clusters and N-grams.

Critical discourse analysis and discourse-historical approach

Critical discourse analysis (CDA) is the critical study of language. It is the development of what has formerly been known as Critical Linguistics. One major feature of CDA is that it is an interdisciplinary field of study. According to Wodak and Meyer (2001), CDA has its roots in a variety of disciplines: rhetoric, text linguistics, anthropology, philosophy, socio-psychology, cognitive science, literary studies, sociolinguistics, applied linguistics and pragmatics.

The general objective of CDA is to analyse “opaque as well as transparent structural relationships of dominance, discrimination, power and control as manifested in language” (Wodak and Meyer 2001, p. 2). In other words, through the critical analysis of discourse, CDA aims at revealing the connections between discursive practices and social structures. It sheds light on the social inequalities and structural hierarchies as reflected in language and discourse. Most importantly, CDA presupposes a dialectical relationship between social/institutional structures and discursive practices. ‘Discourse’, simply put, “constitutes social practice and is at the same time constituted by it” (Wodak et al. 2009, p. 8). One of the major concerns to CDA, according to Fairclough (2003, p. 9), is the ‘ideological effects’ that texts can have “in inculcating and sustaining or changing ideologies”. Fairclough (2003) views ideology as a ‘modality of power’ that seeks to change power relations between groups. Discursive ideological ‘representations’ are one way to subvert social inequalities.

CDA, however, is not a monolithic enterprise, seeing that its paradigm “is not homogeneous” (Wodak et al. 2009, p. 7). Three major varieties are delineable (Wodak et al. 2009). First, the British school draws on the work of Foucault and M.A.K Halliday. Second, the Dutch school suggests a ‘triadic model’ labelled ‘socio-cognitive’ discourse analysis (Wodak and Meyer 2001). Third, there is the German variety, which is deeply influenced by a Foucauldian conceptualization of discourse. There is, however, another variety of CDA that is known as the Vienna School of Discourse Analysis. This school has its roots in Bernstein’s sociolinguistics approach and it is largely informed by the socio-philosophical insights of Critical Theory (Wodak and Meyer 2001; Wodak et al. 2009). The practice and analysis of discourse within this school is known as the Discourse-Historical Approach (DHA).

According to Reisigl (2018, p. 47), DHA “has strong roots in linguistics”, whereas, its theoretical roots are found in Critical Theory (Wodak 2001; Wodak et al. 2009). Developed as a trend of social critique, DHA emphasizes three aspects or forms of critique: text or discourse immanent critique; socio-diagnostic critique and prognostic critique (Wodak 2001). One distinctive feature of DHA is its recommendation to incorporate historical background information about “the social and political fields in which discursive ‘events’ are embedded” (Wodak 2001, p. 65). Another major feature of DHA is that it is ‘problem-oriented’, seeing that the social problems it tackles are multidimensional (Reisigl 2018; Wodak 2001). DHA is also ‘politically-engaged’ (Reisigl 2018, p. 49) since, as a field of critical study, “critical discourse analysis does not pretend to be able to assume an objective, socially neutral analytical stance” (Wodak et al. 2009, p. 8). In connection with this, DHA is ‘application-oriented’ (Reisigl 2018, p. 49). Its critique always tends to disturb the status quo and to highlight social inequalities.

Among the strengths of DHA is the principle of triangulation. In DHA, triangulation is achieved, first, through the use of different approaches and methods. Second, it investigates a large selection of empirical data. Third, it integrates considerable historical information to serve as a background for linguistic analysis (Wodak 2001). In this way, DHA maximizes the validity of its conclusions and minimizes the risk of bias.

Language ideologies

Language ideologies (LIs) is a field of study that branched off North American linguistic anthropology (Piller 2015). After the publication of Silverstein’s article “Language Structure and Linguistic Ideology” in 1979, LIs gained greater momentum as an independent field of enquiry. However, its boundaries were only clearly delineated after the publication of Schieffelin’s et al. (1998) edited volume “Language Ideologies: Practice and Theory” (Vessey 2015, p. 277). The field’s main concern is to highlight the way LIs function as a “mediating link between social forms and forms of talk” (Woolard 1998, p. 3). Put differently, LIs research studies the manifestations of ideology in linguistic forms and how these are related to social organization.

As a concept, LIs have been defined in different ways. For the purposes of this paper, we adopt Woolard’s (1998) definition. According to Woolard (1998, p. 3), LIs are “Representations, whether explicit or implicit, that construe the intersection of language and human beings in a social world”. These representations or ‘constructions’ usually materialize in particular linguistic forms reflecting the underpinning ideological beliefs users hold about language and its structure (grammar, spelling, morphology…). At other times, they surface in debates about language. The present paper is particularly interested in debates about language policy. Debates are a rich source where language ideologies can be discovered, especially debates “in which language is central as a topic, a motif, a target, and in which language ideologies are being articulated, formed, amended, enforced” (Blommaert 1999, p. 1).

Debates are a form of “metalinguistic discourse” as they involve “explicit talk about language” (Woolard 1998, p. 9). In this study a debate is taken to mean the dialogue and exchange of ideas and opinions about language and language policy in articles published in an electronic newspaper. The primary objective is to look at the discourse strategies used in this body of articles and to see how language ideologies are embedded in this discourse about official language policy concerning TM. In this regard, following Spolsky’s (2004) three-dimensional model, language ideologies are intertwined with language policy in a two-way relationship as they usually inform language policy and management which, in turn, often seek to confirm or modify language ideologies.

Methodology

Data collection

The corpus analysed in this study is of the type do-it-yourself corpora (DIY) (McEnery et al. 2006: 71, cited in Mautner 2016, p. 164). Mautner (2016, p. 164) states that DIY-corpora are “purpose-built by individual researchers or small teams to investigate specific research questions”. The corpus constructed is relatively small in size. Guided by the general purpose of the study, which is to investigate language ideologies in media discourse about Tamazight language policy, a total of 658 articles were manually collected from the electronic newspaper Hespress website, resulting in a corpus of 803.444 tokens. The time span stretches from September 2007 up to August 2022, which means that the corpus is synchronic in nature as it includes only “a “snapshot” sample of language from a given limited period of time (Partington et al. 2013, p. 6).

The relevant articles were identified using search terms such as اللغة الأمازيغية /The Tamazight language, الأمازيغية/Tamazight = noun (can also be an Adj. = Amazigh), تفيناغ /Tifinagh (Tamazight script). The articles were further scanned to ensure their pertinence to the research questions before a final decision on inclusion/exclusion was made. The articles were cleaned and spelling mistakes (e.g. the writing of Hamza: glottal stop [ʔ]) which may affect search results were corrected. The titles of the articles and their writers’ names along with publication dates were preserved as a heading of every included article. Anthony’s (2022) concordance program AntConc (vers. 4.1.1) software program was used to construct and explore the corpus.

Data analysis

CL and CDA: a synergy

As abovementioned, this study combines CL and DA methodologies to uncover language ideologies in the discursive construction of TM in media discourse. The combination of CL and DA is now a well-established practice in discourse studies (Ancarno 2020, p. 165; Mautner 2016: 155; Taylor and Marchi 2018, p. 1). Commenting on the relationship between CL and discourse analysis, Sinclair and Carter (2004, p. 10) asserted that “they are the twin pillars of language research”. This trend in language research has been approached differently depending on how practitioners understand the concept of ‘discourse’. For instance, Lancaster researchers draw on critical discourse analysis in their corpus-assisted studies, therefore, their research is more critically-oriented. Other researchers such as Partington et al. (2013) call their approach corpus-assisted discourse studies or CADS with an absence of a ‘critical’ perspective (Baker and McEnery 2015, p. 7). The present paper claims, as aforementioned, to look at language ideologies through a critical lens informed by CDA theory and methods, especially DHA.

In addition to being contiguous disciplines, CL and CDA combination is usually motivated by a number of considerations. Baker (2006, p. 10) notes that the integration of corpus linguistic tools in CDA methodology helps reduce researcher bias. Seeing that total elimination of bias is impossible, CL enables the researcher, at least, to minimize it, especially biases related to the issue of “selectivity” (Baker 2006, p. 12) in that the researcher studies a corpus (body of texts) and not a single text. Similarly, Mautner (2016, p. 156) observes that CL gives CDA analysts the chance to work on large volumes of data which they cannot analyse manually. More interestingly, frequency-based CL tools help CDA analysts offset the subjective interpretation of findings by adding a quantitative dimension to the analysis (Baker 2006, p. 2; Mautner 2016, p. 156). Furthermore, the integration of CL in CDA study designs ensures methodological triangulation (Baker 2006, p. 6; Mautner 2016, p. 156).

In the present study, a host of CL and CDA tools and techniques are used to trace discursively constructed language ideologies in the ongoing language policy debate about TM. Statistical measures such as absolute and relative frequency, collocates analysis and concordance analysis (Brezina 2018) are the major tools used repetitively to aid qualitative analysis of the findings. On the other hand, the study uses CDA technique developed within DHA, namely discursive strategies (Wodak et al. 2009) which, in turn, draw on argumentation theory, especially the analysis of argumentation schemes and topoi (Walton et al. 2008).

Generally, the line of analysis in this paper follows Marchi’s funnelling-down approach (Marchi 2010, cited in Ancarno 2020, p. 177). Ancarno (2020, p. 177) summarizes the protocol used in this approach in three main steps:

-

1.

Word lists/keyword lists to identify key semantic domains, that is, to establish central themes;

-

2.

collocation lists to explore the textual behaviour of key terms, that is, to identify patterns or start classifying terms from the corpus outputs (keyword and collocate lists);

-

3.

Concordance lists to explore further dominant patterns in context.

Procedures

As mentioned earlier, 658 articles were collected manually from the online Moroccan newspaper Hespress. Then, the AntConc software (version 4.1.1) was used to build the corpus with the specifications shown in Table 1. All collocate queries conducted within the corpus used the following settings (Table 2):

It should be noted, however, that AntConc program offers only the likelihood measure for collocation analysis. The search for collocations within the corpus used the following parameters for all queries reported in this paper (Here we use Brezina et al. (2015) collocation parameters notation (CPN) which captures most reported parameters for collocate identification). Nevertheless, the notation is modified to suit the parameters that AntConc offers as follows (Table 3):

Collocate analysis was corroborated with a further analysis of the corresponding concordance lines (KWIC) to provide more contextualized textual evidence for the claims advanced. The analysis of corpus data went hand in hand with a qualitative analysis of the emerging textual data, using an interpretive approach that draws heavily on discourse studies theory, namely the discourse-historical approach.

Findings and discussion

A homogeneous language

Tamazight is generally represented in the corpus as one homogeneous language. However, TM actually may be used to refer to at least four things. First, used as a generic term, it may refer to the different varieties of Berber spoken dialects (Maddy-Weitzman 2012, p. 112) used in Amazigh-populated areas in Morocco such as the Atlas or the Rif regions, namely Tamazight, Tarifit and Tashelhit. Second, it may be used to refer to a historical TM that is now lost. It is also used to designate the recently standardised version. TM is also the name of one of the Berber dialects. In the corpus, TM is predominantly used to refer to a homogeneous and unified language, obscuring the fact that such a variety does not exist in reality. This is because TM is discursively constructed as a unifying bond to bring Amazigh people together.

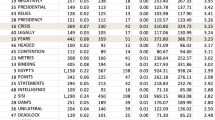

The type “the language/اللغة” was identified as the second top collocate of the word ‘Tamazight/أمازيغية’ (MI (all values), L5-R5, C5, (R)(1); no filter applied), whereas the type “the standardised” and ‘the standard’ are ranked 103 and129 respectively as shown in Table 4 with all the other parameters. The log-likelihood of the collocation “Tamazight Language” (LL = 2408.97; p < 0.05 (3.84 with Bonferroni) is statistically very significant compared to the collocations “Standardised Tamazight/الأمازيغية المعيارية” (LL = 62,763; p < 0.05 (3.84 with Bonferroni) and “Standard Tamazight”/الأمازيغية المعيار” (LL = 59,044; p < 0.05 (3.84 with Bonferroni). The log-likelihood measures clearly indicate a systematic tendency to represent TM. The omission of the term “Standard/ised” even when referring to “Standard Tamazight Language” reveals the commentators’ desire to do away with the negative connotations that the term may conjure up. For instance, the use of the collocate would, apparently, certify the non-existence of a historically homogeneous and monolithic TM prior to its standardisation. Moreover, it would make TM appear as a patchwork of mutually unintelligible varieties.

Tamazight: an urgent case

To give a sense of urgency to the case of the Tamazight language in Morocco, a number of time-related items were used in the corpus. For instance, the item “now/الان” (AF = 131; MI (all values), L5-R5, C5, (R)(1); no filter applied) is a frequent collocate of the search term “أمازيغية*/Tamazight”Footnote 5 with a log-likelihood of (LL = 16,739, p < 0.05 (3.84 with Bonferroni). The examination of the corresponding concordances reveals that this urgency mainly relates to TM officialization, its integration into the educational system and its use in media outlets. The use of the topos of time vitalizes TM: it is not something of the past or that which belongs to the margin, it exists here and now. This temporal relocation /recasting of TM in the discourse about languages in Morocco lends it ‘attractiveness’ as an extremely momentous and very urgent subject for debate. The overall argument boils down to the idea of the “right moment” or what is termed “Kairos” in classic rhetoric. ‘Now’ is the right moment to rectify the situation of TM.

Looking closely at the list of collocates, there emerge other collocations that accentuate the sense of urgency with which TM is spoken about. The term “Speeding up/تسريع” (LL = 23,954, p < 0.05 (3.84 with Bonferroni) relates to the topics (processes) of TM integration in education, officialization and the use of Tifinagh script for writing. On the other hand, the term “تأجيل /delaying, postponing” relates to the same set of topics, but it also relates to its use in the parliament. This collocate is used in most occurrences to blame the State for the “intentional delay” in enabling TM to assume its role as an official language. It is claimed that this dilatory tactic is part of a premeditated plan to curb and render TM dysfunctional as a language.

A timeless language

Appeal to history is a well-established argumentative tactic, especially when arguing questions that relate to existence. In the corpus under analysis, the type “Tamazight, Amazigh/ الأمازيغية” emerges as the first top collocate (MI (all values), L5-R5, C5, (R)(1); no filter applied) of the lemma “history/تاريخ*” with a log-likelihood of (LL = 28,907). Concordances (see Table 5) show that the topos of history is mainly invoked as a witness to the timelessness of the TM language and Amazigh culture as a whole. Besides, this appeal to historical origins seeks the legitimation of the present agendas of TM advocates, namely its officialization and use in public domains.

This appeal to history as a source of legitimation for the “Amazigh Cause” is further sought by the use of collocates such as the collocate الماضي/(the) Past. The collocation is mainly used to represent TM as a long-living language that has gone through natural stages of development. The gist of the argument is that TM, as a language, has been the subject of academic and scientific study and it has developed its own dictionaries. Moreover, the concordances show that the appeal to a “remote past” is used to justify the current debate about TM: TM officialization has always been the subject of a continuing debate in the country and, therefore, it is totally legitimate to raise issues related to TM once again. More interestingly, the “past” is represented as a “burden” (a moral one) that weighs heavily on the State being the sole culprit for the historical marginalization of TM. Thus, the promotion of TM is what would absolve the state of this historical ‘sin’. This scheme of argument which is an argument from consequences (Walton et al. 2008) can be exemplified as follows:

سيساهم النهوض بالأمازيغية في التخلص من مخلفات الماضي وفي نشر ثقافة الديمقراطية والتعددية الثقافية والمواطنة والمساواة والتواصل مع كافة المغاربة.

The promotion of the Tamazight language would help get rid of the legacy of the past and spread the culture of democracy, multiculturalism, citizenship, equality and dialogue between all Moroccans.

Notwithstanding the essentiality of the past in any debate about origins, the argument for originality would be incomplete if it does not anticipate the future. The item “Future/مستقبل” collocates quite often with the query term “أمازيغية*/Tamazight” (LL = 20,931) and the examination of its concordances reveals interesting results. The collocation indexes the theme of uncertainty about the future of TM. Doubting the future of TM is clearly used as a scapegoating strategy (Wodak et al. 2009) to make the “moral burden” even heavier on the state. Doubt here functions as a defence tactic (through pressuring) that seeks to put more pressure on the state to act against what it is constructed as a possible “bleak future” awaiting TM. The use of the topos of threat, that is, if the state does not act now in favour of TM, TM will have a very bad future, not only strengthens the argument for TM promotion but it also seeks its protection and valorisation.

On the whole, the use of these terms that have a temporal reference spanning the past, present and future, attests to the endeavour to construct continuity through time. This is what is called the presupposition of/emphasis on continuity (Wodak et al. 2009: 39). TM in the corpus is constructed as a timeless language which has always existed, still exists and will always exist. This not only adds more value to the revitalization efforts sought by TM advocates, but it also strategically distances TM from any possibility of decay.

A modern ‘scientific’ language

Formal education is one of the most important gateways to strengthening a language and elevating its status and one way to ensure its maintenance and development. It offers ample language dissemination possibilities to a large section of the population, namely the young generation. In the corpus under analysis, TM is constructed as a full-fledged modern language that is capable of assuming all possible roles expected from a language in a modern society, chiefly roles in the domain of education. Throughout the corpus, TM advocates insist on teaching TM as a school subject and on its use as a medium of instruction to teach content subjects at school, especially science. Table 6 shows the top four collocates of the search term “أمازيغية*/Tamazight” ranked by frequency:

Concordances analysis of the most frequent collocate “تدريس /teaching” reveals that the focus is on four main points. First, the teaching of TM should not be limited only to the primary level, it should be expanded to the secondary and tertiary levels, too. Second, Latin script is the most suitable choice to promote and make TM gain new speakers easily and quickly. Third, TM should be a compulsory school subject. Lastly, TM should be used as a medium for teaching science at school.

One can easily notice that these four points revolve around the idea of prestige. For instance, given the prestige associated with the secondary level being a critical stage at which students sit for high-stakes national exams (e.g., Baccalaureate) and the tertiary level which is associated with refined scholarly knowledge, the teaching of TM or its use as a medium of instruction at these levels would offer TM a more prestigious status along with other languages. More importantly, such a step would help TM do away with its association with the primary level, an ‘infantile’ stage associated with immaturity. Similarly, the use of the Latin script would confer more prestige on TM, building on the symbolic power of the most widely used Western languages (e.g. French and English). Moreover, the call for using TM to teach science in schools clearly capitalizes on the stereotypic representation of science as a prestigious discipline.

In connection with its integration into the educational system, the collocates “قادرة/able” and “عاجزة/unable” are used as qualifiers of TM, and they are mostly used with the verb ‘allege’ (the opponents of TM allege it is unable to teach school subjects, especially science). For instance, the concordances of the collocate “قادرة/able” show that it is more often associated with the claim that TM is ready to fulfil its roles in key domains: science education, literature, translation, media, medicine and administration. Talking about science, in particular, one text uses this analogical argument scheme: Arabic has been unjustly accused of failing to accommodate modern scientific terminology, therefore, we should not commit the same error in the case of TM.

An ‘original’ language in need of legal protection

According to Spolsky (2021, p. 172), “the status of language is set by laws and acts of the parliament”. Collocation analysis shows that the legal protection of TM is a recurrent topic in the corpus. Generally, TM is represented as a language that urgently needs legal protection. This comes as no surprise as TM has been only recently standardised and officialised in Morocco (2011 Constitution). The call for the protection of the status of TM through legal legislation is motivated by several aspirations. First, there is the hope to protect the language from decay and to strengthen its status as an official language vis-a-vis other powerful languages, mainly Arabic and French. Also, having a legal status not only guarantees the dissemination of TM across different domains of use but also protects and consolidates the linguistic rights of its speakers. Concordance analysis of the lemma (official/ رسمي*), which collocates with the search word “Tamazight/أمازيغية*” (LL = 498,406), reveals that there is a prevailing doubt cast on the utility of enacting laws and regulations to maintain and elevate the status of TM. One recurrent justification for this stance is that laws are of no avail if they are not effectively put into action. For instance, much criticism is levelled at the Organic Law 26.16 issued in 2019 and which determines the procedural steps that should be taken to officially integrate TM in education and in the "public domains of priority”. The following sample quotations show how the law was talked about in the corpus:

(1) ولأن مشروع القانون التنظيمي يحصر الترسيم فيما هو شفوي ورمزي وديكوري، كما سبق شرح ذلك، مع غياب مطلق لأية خطة للاستعمال الكتابي الرسمي للأمازيغية الموحّدة في المستقبل، فإن تحديد أقصى مدة لتفعيل الطابع الرسمي للأمازيغية في 15 سنة، هو مجرد كذبة...

Given the fact that the Organic Law restricts the officialization (of TM) to what is oral, symbolic and ‘decorative’, as explained before, in a total absence of any plan to officially use the written form of the ‘unified’ Tamazight in the future, setting 15 years as the limit before which the official character of TM should be implemented is a mere lie...

(2)‘bonus’ خزعبلة “القانون التنظيمي” تلقفها المدافعون عن الأمازيغية كنوع من أي كعلاوة أو جائزة إضافية ربحتها الأمازيغية في حين أن “القانون التنظيمي” هدية مسمومة هدفها دك الترسيم أو تمييعه وتأجيله وتقييده بعوامل الزمن والبيروقراطية

The nonsensical Organic Law was received by the proponents of TM as a ‘bonus’ or another prize gained by TM. While, in fact, the Organic Law is a poisonous gift that aims at nullifying the officialization and postponing and restricting it through continuous delay and bureaucracy.

What this analysis shows is an expressed mistrust in the official texts which regulate the officialization of TM. It even extends to a mistrust in the original intentions of the state. The Constitution is itself subjected to harsh criticism for the way the officialization of TM was formulated in its 5th article.

Tamazight as a “cause”

The officialization and the real implementation of the official character of TM in public domains were and remain core demands of the Amazigh Movement. The MovementFootnote 6 represents its struggle for more rights, be it cultural, political, economic or linguistic, as the “Amazigh Cause”. The corpus under analysis offers evidence for this claim. The query term “أمازيغية*/Amazigh (adj.)” significantly collocates with the word “the Cause /القضية” (LL = 130.94) and with its different forms as shown below in Table 7:

Seeing the fact that TM language is placed centre-stage in the political struggle for the ‘Amazigh Cause’, it is discursively constructed as the most cherished symbol of the Amazigh identity. The term “identity/ الهوية” interestingly collocates with the query term “أمازيغية*/Amazigh (adj.)”. The collocation has a log-likelihood of (LL = 77,277). Thus, it is quite natural for a politicized discourse to utilize the language of sympathy and antipathy. TM, and the ‘Amazigh’ Cause in general, are represented as having “proponents/ أنصار” (LL = 135,524) and also "enemies/ خصوم” (LL = 41,509). This division of the world into US/Them is just another discourse strategy that the Amazigh Movement makes use of to construct strong in-group solidarity.

As is the case with any political movement defending a ‘cause’, Amazigh Movement does have ‘demands’. Among these is the officialization of TM, which emerges as a predominant theme in the corpus, especially in texts written before the 2011 referendum on the new Constitution. The following is a sample of relevant concordances (Table 8):

A ‘victim’ language

Based on the results that emerged from the search for collocates of the query term “Tamazight/أمازيغية*” and which clearly demonstrate the use of the human rights lexicon, further research was conducted to explore how human rights discourse was used to make a case for TM in the corpus. It turned out that human rights terminology is used systematically in the corpus. For instance, the collocation “human rights/ *حقوق ال*نسان” occurs 208 times (RF = 2.5 per 10.000). Given the small size of the corpus (803.444 tokens), this is a telling result. Moreover, there is a relatively good distribution of terms such as “equality /المساواة” (R% = 10%) and “discrimination / الميز” (R% = 5%) (the range2 reported here is that of the most frequent term in the wordlist). Table 9 shows statistics for the lemma “equality / *مساوا*”.

As these statistics are not sufficient as evidence, a search for the collocates of the term “equality /*مساوا*” was conducted. A concordance analysis of the collocations, namely “equality between /المساواة بين” and “equality with /المساواة مع” reveals that TM advocates' main concern is the equal treatment of TM and SA. This insistence on language equality is in line with the representation of TM as an “underprivileged” language which is, despite being constitutionalized, still inferior to Arabic and French. The collocates “deprivation/حرمان” (LL = 30,345), “marginalization/إقصاء” (LL = 52,297) and “denial (or prohibition)/منع” (LL = 34,627) point to the discursive strategy of victimization. TM is represented as a “victim” of the unjust management by the State. The State is generally blamed for the intentional and continuous 'marginalization' of TM (along with its speakers). For example, the lemma “marginalize/*هم*ش*” is a frequent collocate of “Tamazight”. The following is a sample of the concordances that make strong claims about the marginalization of TM (Table 10):

In the same vein, TM is anthropomorphized as a language that “suffers” from the plight of marginalization and, therefore “needs” some kind of special treatment. The verb “needs/تحتاج” (R% = more than 4%) is a significant collocate of “Tamazigh/أمازيغية*” and the two-gram “Tamazight needs/الأمازيغية تحتاج” occurs 17 times. This appeal to pity is part of a more general argumentation scheme (running throughout the corpus) and can be defined as argumentation from distress (Walton et al. 2008). The argument scheme has the following structure:

Premise I: Individual x is in distress (is suffering).

Premise 2: If y brings about A, it will relieve or help to relieve this distress.

Conclusion: Therefore, y ought to bring about A.

In the case of TM, the scheme can be rendered as follows:

Premise I: TM is in distress (is suffering).

Premise 2: If the State brings about TM promotion, it will relieve this distress.

Conclusion: Therefore, the State ought to bring about TM promotion.

Supporting this claim is the fact that the term “the promotion/ النهوض” (AF = 82, rank = 95) is among the first 100 words that collocate with the search term “Tamazight/أمازيغية*”. An example of the argumentation from the distress scheme used in one of the texts can be illustrated as follows (Fig. 1):

Based on what has been presented so far, three related topoi can be identified in the argumentation for a better situation of TM in the Moroccan linguistic market, namely the topos of humanitarianism, the topos of justice and the topos of responsibility (Wodak and Meyer 2001). The promotion of TM is seen as a basic linguistic human right that should be protected by the State (topos of humanitarianism). One way to achieve this is to ensure that the state's management policy of TM and Arabic is based on the principle of equality (topos of justice). And, it is the state that should assume full responsibility for the long-lasting marginalization of TM (topos of responsibility).

Conclusion

Benefiting from the synergy that the combination of CL and CDA offers, this paper attempted to uncover some of the language ideologies circulated in media discourse about the Tamazight language in Morocco. Since 1991, Tamazight has been one of the major contentious topics in a much-heated debate about language policy in the country. This debate about the status and value of Tamazight is still going on up to the present moment. Different policy agents steer the debate based on their respective cultural and political ideologies. These ideologies most often transfigure into language ideologies which, in turn, come to the surface in the circulating meta-linguistic discourses about the different varieties that make up the linguistic market in Morocco.

This paper demonstrates that language ideologies effectively orient and shape language policy debates. Through continuous strategic discursive representation in media discourse, TM is reinstated as a vital language and a core constitutive element of the Moroccan cultural identity. Based on historical, political and linguistic grounds, several discursive strategies were employed in building a normative discourse about TM. And, as the analysis of the corpus showed, discourses of historicity, homogeneity, modernity, ‘scientificity’ and victimhood are some of the major discourses disseminated in the debate about the situation of TM in Morocco. Compared to the fate of most minority languages, TM is construed as a ‘timeless’ variety that resisted decay throughout its long history and, therefore, is capable of resisting the oblivion it is subjected to today. The revitalization of a language through officialization is by no means enough to guarantee its use and maintenance. Hence, in order for a historical language which has been chiefly used orally for generations like Tamazight to find a place in the modern world, it has to be able to flawlessly function in the central domains of modern society. It is for this particular reason that TM is constructed in the corpus as a vital, modern and scientific language capable of being used as a medium of instruction in school just as any other language.

That said, the marriage between CL and CDA is not without methodological problems. One of the issues faced in this fruitful combination is ‘researcher bias’. In this study, to a great extent, the process of text selection was objective in that the inclusion of texts was based solely on their relevance regardless of the ethnic or political affiliation of their authors. Texts written by advocates and proponents were indiscriminately included as long as they tackled some aspect of the Tamazight language in Morocco. Nonetheless, the choice and focus on a particular set of linguistic data may be unconsciously or rather cognitively biased. In this regard, Baker and McEnery (2015, p. 9) comment on the problematic issue of bias in CL by observing that “it is more helpful to accept that there is no such thing as unbiased human research”. On the other hand, CDA practitioners respond to the much-stated criticism levelled at CDA concerning the selection and interpretation of texts by stating that “CDA, unlike most other approaches, is always explicit about its own position and commitment” (Fairclough 1996, cited in Meyer 2001a, b, p. 17).

Additionally, concerning corpus construction, ‘author bias’ may affect statistical results if too many texts by the same author are included. For instance, in our corpus, the texts of one ‘prolific’ writer were cautiously approached to prevent his ‘authorial biases’ from colouring the results of the analysis. Accordingly, results such as word frequency were further scrutinized for their source files to ensure that they are evenly spread in the corpus and not originating in the writings of one writer. The representativeness of the corpus is another issue at stake. The corpus analysed in this study is only a small sample of language used in Moroccan media discourse as its focus is exclusively on one electronic newspaper. So, given its relatively small size, the corpus faces issues of representativeness and any conclusions may not be conclusive and remain debatable on the ground of linguistic counter-evidence.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

General Population and Habitat Census, 2014.

Tamazight is used as a generic name for the three main Berber varieties one of which is also called Tamazight. All references in this paper but this one is to Tamazight (TM) as a hypernym.

Agadir Charter for Linguistic and Cultural Rights,1991.

Royal speech made on August 20th to commemorate the 41st anniversary of the Revolution of the King and the People, 1994.

The asterisk is a search setting that indicates zero or more characters.

The Amazigh Movement is a constellation of several associations and individuals whose aim is to better the situation of Amazigh people in Morocco.

References

Ancarno C (2020) Corpus-assisted discourse studies. In: Georgakopoulou A, De Fina A (eds) The Cambridge handbook of discourse studies. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 165–185

Anthony L (2022) AntConc (version 4.1.1) [Computer Program]. Waseda University, Tokyo. https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software. Accessed 7 Jan 2023

Baker P (2006) Using corpora in discourse analysis. Continuum, London

Baker P (2010) Sociolinguistics and corpus linguistics. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh

Baker P, McEnery T (2015) Corpora and discourse studies: integrating discourse and corpora. Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire

Baker P, Gabrielatos C, Krzyzanowski M et al (2008) A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press. Discourse Soc 19(3):273–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926508088962

Blommaert J (1999) The debate is open. In: Blommaert J (ed) Language ideological debates, vol 2. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, pp 1–38

Boukous A (2005) Dynamique d’une situation linguistique: le marché linguistique au Maroc. In: Tozy M (Reporter) Dimensions culturelles, artistiques et spirituelles. Contributions à 50 ans de développement humain et perspectives 2025. Rabat, pp 17–20

Brezina V (2018) Statistics in corpus linguistics: a practical guide. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Brezina V, McEnery T, Wattam S (2015) Collocations in context: a new perspective on collocation networks. Int J Corpus Linguistics 20(2):139–173. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.20.2.01bre

Fairclough N (2003) Analysing discourse: textual analysis for social research. Routledge, London

High Commission of Planning (HCP) (2014) General population and habitat census. http://rgphentableaux.hcp.ma

Hunt D, Harvey K (2015) Health communication and corpus linguistics: Using corpus tools to analyse eating disorder discourse online. In: Baker P, McEnery T (eds) Corpora and discourse studies: integrating discourse and Corpora. Palgrave Macmillan, Hampshire, pp 134–154

Leech G (1992) Corpora and theories of linguistic performance. In: Svartvik J (ed) Directions in corpus linguistics. De Gruyter, Berlin, pp 105–122

Maddy-Weitzman B (2012) Arabization and its discontents: the rise of the Amazigh movement in North Africa. J Middle East Afr 3(2):109–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520844.2012.738549

Mautner G (2016) Checks and balances: How corpus linguistics can contribute to CDA. In: Wodak R, Meyer M (eds) Methods of critical discourse studies, 3rd edn. Sage, London, pp 154–179

McEnery T, Hardie A (2012) Corpus linguistics: method, theory and practice. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

McEnery A, Xiao Z, Tono Y (2006) Corpus-based language studies: an advanced resource book. London: Routledge.

Meyer M (2001a) Between theory, method, and politics: positioning of the approaches to CDA. In: Wodak R, Meyer M (eds) Methods of critical discourse analysis. Sage, London, pp 14–31

Meyer M (2001b) The discourse-historical approach. In: Wodak R, Meyer M (eds) Methods of critical discourse analysis. Sage, London, pp 63–64

Partington A, Duguid A, Taylor C (2013) Patterns and meanings in discourse: theory and practice in corpus-assisted discourse studies (CADS), vol 55. John Benjamins Publishing, Amsterdam

Piller I (2015) Language ideologies. In: Tracy K, Sandel T, Ilie C (eds) The international encyclopedia of language and social interaction. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, USA, pp 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118611463.wbielsi140

Reisigl M (2018) The discourse-historical approach. In: Flowerdew J, Richardson JE (eds) The Routledge handbook of critical discourse studies. Routledge, London, pp 44–59

Sadiqi F (2011) The teaching of Amazigh (Berber) in Morocco. In: Fishman JA, Ofelia G (eds) Handbook of language and ethnic identity. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 33–44

Silverstein M (1979) Language structure and linguistic ideology. In: Clyne PR, Hanks WF, Hofbauer CL (eds) The elements: a para-session on linguistic units and levels. Chicago Linguistic Society, Chicago, pp 193–247

Sinclair J, Carter R (2004) Trust the text: language, corpus and discourse. Routledge, London

Spolsky B (2004) Language policy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Spolsky B (2021) Rethinking language policy. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh

Stubbs M (1993) British traditions in text analysis: from Firth to Sinclair. In: Baker M, Francis G, Tognini-Bonelli E et al (eds) Text and technology: in honour of John Sinclair. John Benjamins Publishing, Philadelphia, pp 1–36

Taylor C (2008) What is corpus linguistics? What the data says. ICAME J 32:179–200

Taylor C, Marchi A (eds) (2018) Corpus approaches to discourse: a critical review. Routledge, London

Teubert W (2005) My version of corpus linguistics. Int J Corpus Linguistics 10(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1075/ijcl.10.1.01teu

Thompson G, Hunston S (2006) System and corpus: Exploring connections. Equinox, London

Vessey R (2015) Corpus approaches to language ideology. Appl Linguis 38(3):277–296. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amv023

Walton D, Reed C, Macagno F (2008) Argumentation schemes. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Wodak R (2001) The discourse-historical approach. In: Wodak R, Meyer M (eds) Methods of critical discourse analysis. Sage, London, pp 63–64

Wodak R, Meyer M (2001) Methods of critical discourse analysis. Sage, London

Wodak R et al (2009) The discursive construction of national identity. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh

Woolard KA (1998) Introduction: language ideology as a field of inquiry. In: Schieffelin BB, Woolard KA, Kroskrity PV (eds) Language ideologies: practice and theory. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 3–50

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the librarians and ICT technicians in the FLHS-Mohammedia for their help.

Funding

This study did not receive any specific financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

We hereby state that both authors invested equal efforts in writing this paper. For the first main author, he collected the data and built the corpus and he also took up the task of writing the first draft under the continuing guidance of the second author. Both authors contributed equally to the analysis, discussion of the results and conclusions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Khalid, L., Said, F. Language policy debate and the discursive construction of Tamazight in Moroccan news media: a corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis. SN Soc Sci 3, 172 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-023-00725-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-023-00725-4