Abstract

Few experimental attempts have been reported comparing the sentencing decisions of professional judges and that of laypeople using the same criminal case. This study examined the sentencing justifications (retribution, incapacitation, general deterrence, and rehabilitation) and the resulting imprisonment sentencing differences between Japanese judges and laypeople. The online quasi-experiment comprised 48 judges and 199 laypeople. Participants read a fictional murder case, and they were asked to respond on two types of justification scales and enter the number of years of imprisonment for the offender. Both the judges and laypeople placed the highest importance on retribution in the numerical input scale, which failed to detect the difference. The Likert scale revealed that judges add less weight to rehabilitation, incapacitation, or general deterrence, than laypeople. As predicted, the number of imprisonment years chosen by judges was significantly shorter than that of laypeople. The differences in justification can cause disagreements between judges and laypeople. This study suggests that judges do not give much consideration to justifications and decide on sentencing based on different criteria than laypeople. Differences from previous studies related to the judges’ emphasis on justification and the disparity of sentences are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although judges have been demonstrated to be better decision makers than laypeople, even professionals rely heavily on intuitive reasoning in their decisions (Englich et al. 2006; Guthrie et al. 2007; Rachlinski and Wistrich 2017). Previous studies have consistently demonstrated that laypeople’s intuitive reasoning is based on retributive justification (Carlsmith 2006; Carlsmith et al. 2002; Keller et al. 2010; Oswald et al. 2002; Rucker et al. 2004; Watamura et al. 2011; Weiner et al. 1997). However, few attempts have been made to examine the intuitive reasoning of judges compared to that of laypeople, such as jurors or lay judges. Therefore, it is unclear if judge’s intuitive justification for determining punishment differs from that of laypeople and if justification differences also cause differences in sentence severity. Although stated justifications may not predict actual judgments (Carlsmith 2008), justification is a fundamental decision strategy in intuitive reasoning. It influences the selection of information and its evaluation systematically (Carlsmith 2006; McFatter 1978) and determines the severity of punishment (Brubacher 2018). Therefore, a comparison of judges and laypeople in intuitive reasoning, using justification as a cutoff point, is a useful approach to comprehensively explain the differences between them.

Of course, professional judges do not base their decisions on intuition alone. According to the “sentencing frame theory” (Harada 2006), the sentencing decisions of Japanese judges in court are made within the upper and lower limits of a “frame” for each crime. The law that defines the frame is based on laypeople’s sense of justice (Mastumoto 2006). Therefore, “relative retributivism,” with retribution as the default, balances against utilitarian justification, such as incapacitation. This idea is like the Penal Code in the U.S.Footnote 1 and the idea of merging “the offender’s blameworthiness” and “protection of the community” in focal concerns theory (Crow and Bales 2006; Crow and Gertz 2008; Steffensmeier and Demuth 2001). The first parameter that determines sentencing within this frame is the average sentence, formed by accumulating data on similar cases. Due to this constraint, judges’ decisions in Japan are relatively homogenous, and disparity is small, even without sentencing guidelines (Harada 2006). The second parameter, discretion, considers a myriad of information without clear rules, leaving room for intuitive reasoning.

If judges and laypeople discuss sentencing based on different justifications, they are likely to disagree sharply with each other (Eisenberg et al. 2005; Hastie 2000). For example, if judges do not value retribution as much as laypeople, disputes may arise through laypeople arguing that the sentences should be heavier for serious crimes. If judges place more emphasis on rehabilitation, their sentencing of a defendant without a prior conviction (i.e., little need for rehabilitation) will be lenient, and a dispute will arise from laypeople who try to punish the defendant severely. There are many possible patterns, but the differences in justification would be barriers to sentencing discussions between judges and laypeople. As the rate of guilty verdicts in Japan exceeds 99% (Ramseyer and Rasmusen 2001), whereas 68% of defendants charged with felonies in the US are reported as guilty, the issue in most cases in Japan is not that of the judgment of guilt or innocence but the severity of the sentence and its justification. Under Japan’s jury system, three judges and six lay judges confer to decide the sentence for serious crimes such as murder, robbery, arson, and rape. If there is no consensus, a majority vote is taken. In particularly heinous cases, the death penalty may be the ultimate option. It is quite possible for both sides to come to different conclusions, even if their decisions are based on the same information. For this reason, it is essential to examine whether there is a discrepancy in the fundamental decision strategy (justification), and sentence severity between judges and laypeople. This information would make it easier for judges and laypeople to agree on deliberations while also revealing the reality of what judges consider to be justice in their professional capacity.

Justification classification

How does justification of sentencing differ between judges and laypeople? Before examining this question, the concept of “justification” in the current study should be defined and classified. According to Carlsmith (2006) and Spohn (2009), justification of sentencing decisions has been the central area of conflict between Kant’s (1790, 1952) retributive theory and Bentham’s (1843) utilitarian theory (Vidmar and Miller 1980). Based on these two theories, there are two main types of sentencing justifications: retributive (or desert based) and utilitarian. The retribution approach can be considered a past-oriented view of justification, in which the offender is given a punishment that is commensurate with the severity of the crime, thereby reversing the moral imbalance. Therefore, according to the retribution approach, punishment is proportional to the severity of the crime. Utilitarian justification is a future-oriented, pragmatic perspective in which the aim is to deter future crimes by influencing criminals or society in general (e.g., Carlsmith 2006; Spohn 2009; Vidmar and Miller 1980; Weiner et al. 1997). Utilitarian justification can be categorized into incapacitation, general deterrence, rehabilitation (or education), and others. Most social psychological research on sentencing has focused on these four types of justification—retribution, incapacitation, general deterrence, and rehabilitation—and has examined the type that is most likely to be important in sentencing judgments by laypeople.

Differences in justification between judges and laypeople

As mentioned earlier, few studies have compared judge’s intuitive justifications with those of laypeople, perhaps because of the rarity of the profession. However, Warner et al. (2019) conducted unique research in which 987 Australian jurors were asked to choose one of the most important post-conviction justifications for a serious crime and compare it to the judge’s sentence. The results showed that by far the most common justification by the jurors corresponded to retribution. However, judges ranked general deterrence as the most important justification, followed by incapacitation and retribution. Although the rankings varied slightly by crime type, the differences in justification between judges and laypeople were more pronounced in the Australian samples.

Thus, what difference does such a difference in justification make in the resulting sentencing? Theoretically, judges who are experienced and familiar with two parameters (i.e., the average sentences and discretion), by balancing various justifications, should provide lighter sentences with less variation than laypeople who are most concerned with retribution. In Japan, a study was conducted in which the participants were asked to read short vignettes (about 200 words) of some murder cases and then make judgments about each defendant’s sentence (Training and Research Institute for Court Officials 2007). The results demonstrated that the judges sentenced the accused to lighter sentences than the laypeople, and the variation among the sentences was less. For example, if a defendant had a prior conviction for avarice- or resentment-type murder, laypeople who sentenced the defendant to prison gave an average sentence length of 12.6 years (SDFootnote 2 = 4.3), whereas the average sentence from the judges was 11.9 years (SD = 2.4). The difference is slight regarding imprisonment alone, but the other options of “life imprisonment” and “death penalty” were chosen by 18.9% and 7.3% of laypeople, respectively, compared to 0.9% and 0% of judges. These responses cannot be translated into imprisonment, but it does suggest that judges impose lighter and less dispersed penalties than laypeople. When other murders with a motive other than the examples above were also examined, such as lover’s suicides, resistance to persistent violence, and gang warfare types, judge’s sentences were lighter than those made by the laypeople for all of them, and the SD of the sentences was about half that of laypeople. The tendency for judges to impose lighter and more consistent sentences (i.e., with less variation) than laypeople has also been found in Germany (Sporer and Goodman-Delahunty 2009) and the US (punitive damage decision making) (Eisenberg and Heise 2011; Eisenberg et al. 2006). However, this Japanese study (Training and Research Institute for Court Officials 2007) was based on short vignettes that did not include detailed information such as the background of the crime, the attitudes of the accused, or the prosecutor’s sentencing request. In other words, this study lacked the necessary judgmental material and demonstrated sentencing decisions based on the participant’s own perceptions regarding the types of murder cases. While judges deal with numerous cases, laypeople are more likely to imagine only serious cases that would be reported in the news (i.e., availability heuristic). This perception would naturally result in more severe sentences by laypeople; in the absence of a reference numerical anchor for sentencing, such as a prosecutor’s sentencing request, the variation would be greater. Therefore, it is impossible to reveal the differences in justification between judges and laypeople without comparing them under conditions that leave the least room for self-interpretation by providing more material and information about the plea as if it was an actual trial. In this study, the experimental material was prepared by modifying real sentences for research purposes. This practice allowed us to compare the justifications and resulting sentences of judges and laypeople under the condition that they had almost all the information necessary to make a sentencing decision. The case we chose was a murder caused by financial troubles. Although it is necessary to examine other cases as well, in Japan, only serious cases are subject to jury trials. Murders due to financial trouble are a relatively common type of homicide (Ministry of Justice 2018). By using a typical case in Japan as a subject, we tried to clarify the differences between judges and laypeople as a baseline.

Methods

Overview

We attempted to recruit judges through the courts. However, it was difficult to obtain their cooperation due to their unwelcoming climate of psychological research (Fukushima et al. 2021) and legal restrictions (e.g., confidentiality). Therefore, we decided to solicit anonymous, voluntary participation through an internet research company, Rakuten Insight, Inc.Footnote 3 The list of this internet company has about 2.2 million participants (as of April 2019) from various occupations throughout Japan and has a long track record of providing data for various surveys conducted by universities and government agencies. Moreover, recent studies (e.g., Gottlieb 2017; Twardawski et al. 2020; Vardsveen and Wiener 2021) have conducted criminal trial experiments with participants obtained through such an Internet company. We recruited 50 judges for the current study by screening participants whose occupation was registered as active judges from this company’s list. At the same time, 200 members of laypeople were randomly recruited from other occupations. In 2020, there were 2798 people registered as active judges (Japan Federation of Bar Associations 2020), and about 76 million Japanese adults in their 20s to 60s nationwide, who were the subjects of the current study (Statistics Bureau of Japan 2020). Participants sampled from these populations read the text displayed on the invitation screen that guided them through the screening phase of the “Questionnaire on Criminal Cases,” which explained that they were to answer the questionnaire as judge or as lay judge, respectively. They clicked on the “Agree and Start Questionnaire” button and submitted their informed consent. Shopping points worth about 30 cents were paid for gratuities after participation. Forty-eight judges (Mage = 49.6, SD = 8.5, 6 females) and 199 laypeople (Mage = 44.3, SD = 13.7, 100 females) were included in the analysis, excluding two judges and one layperson who responded to the dummy questionFootnote 4 incorrectly because we could not ensure that they were answering honestly. Questions, data, and experimental material are available in the Open Science Framework. At the beginning of the study, we measured moral values as a personal characteristic that might be involved in the sentencing decision. We asked judges and laypeople to respond to the Japanese version of the Moral Foundation Questionnaire (Graham et al. 2011; Kanai 2012). However, we excluded it from the subsequent discussion, owing to the low alpha coefficients of the questionnaire items and because it was explorative outside the main focus of the discussion. This study was conducted with the approval of the ethical review committee of the university to which the researcher belongs (Approval Number: HB020-023).

Procedure

Presentation of experimental materials

Along with the following instructions, we then asked the participants to read a text describing a fictional murder consisting of approximately 1900 characters in Japanese (see the English version of the full text in Supplementary Materials).

The following sentences relate to one murder case (The descriptions of the concurrent crimes, such as the confiscation of the murder weapon have been omitted). At the time of the crime, the accused man was 45 years old and an office worker. The facts of the case are not in dispute. The prosecutor asked for 16 years imprisonment, but the defense attorney petitioned for a reduced sentence, arguing that the victim was also at fault to a certain degree. Please read the following text and answer the questions with the intention of judging the defendant in this case.

To summarize the text, the defendant had made a real estate investment of ¥85,000,000 (approximately $81,000) after being solicited by the male victim but fell into a large debt after the investment failed. The defendant became angry with the victim, who was soliciting further investments and stabbed him more than a dozen times with a kitchen knife, killing him. Along with our purpose of comparison under conditions with enough organized material and information like an actual trial and where the room for self-interpretation was minimized, participants could freely refer to this text as many times as they wanted while answering the questions.

This hypothetical case was created by us using a real murder case as a model and the sentence was handed down to the accused in that trial as a reference. Thus, the text included sufficiently detailed information about the circumstances and background of the crime, the time of the murder, the defendant’s attitude after the crime, and other details that would help participants decide the sentence. Finally, information about the prosecutor’s request for a 16-year prison sentence was presented.

Justification

Four types of justification were presented to the participants—retribution, incapacitation, general deterrence, and rehabilitation—to determine which justification was important in their sentencing of the defendant. The descriptions of these justifications were taken from Berryessa’s (2018) study. The participants were asked to enter a numerical value from 0 to 100 next to each of these justifications to achieve a total of 100%. The order of the presentation was randomized for each participant.

How much weight do you give to each in determining the punishment for the defendant in this case? Please answer, so the total is equal to 100%.

Retribution relies on the idea that for justice to be served, an offender deserves to be punished in a manner that is proportionate to the severity and moral heinousness of the committed crime.

Incapacitation aims to remove offenders from society to protect the general public from future unlawful behavior.

General deterrence attempts to prevent the future committal of crimes through the threat of future punishments that outweigh an individual’s motivation to commit future criminal acts.

Rehabilitation seeks ways to actively reform and address the underlying reasons for an offender’s criminal behavior so that an individual will not reoffend.

The numerical input response method was both original to this study and a challenge. Most previous studies have adopted the approach of asking people to rate how much importance they place on each of the justifications (e.g., Carlsmith 2008; Carlsmith et al. 2002; Orth 2003; Twardawski et al. 2020). However, the respondents tended to provide importance to all the justifications, which made it difficult to distinguish which of the justifications formed their level of punishment (Spiranovic et al. 2012; Warner et al. 2019). Further, Warner et al. (2019) demonstrated that choosing a single justification was difficult for respondents; in their study, many laypeople chose more than one justification, even though they were instructed to choose just one. The same occurred with the judge’s sentencing statements. On average, three to four justifications were mentioned, and only in one-third of the cases could the most important justification be singled out. According to Robinson (1987), sentencing justification is normally a hybrid of retribution, incapacitation, general deterrence, and rehabilitation. To avoid these problems, the participants in our study were asked to indicate the relative ratio of the importance of each type of justification when the total was 100%.

In addition, we measured justification on a conventional Likert scale. Six justifications were directly extracted from Orth’s (2003) scale: retribution, incapacitation, general deterrence, rehabilitation, deterrence of the offender, and positive general prevention. It is to be noted that it constituted six justifications, and not the original four given by Berryessa (2018). The two additional justifications (deterrence of the offender and positive general prevention) were conceptually related to the original four, so it was essential that they were included. The participants responded to how important each of the following items were in punishing the defendant using a six-point scale (0 = very unimportant, 1 = unimportant, 2 = somewhat unimportant, 3 = somewhat important, 4 = important, and 5 = very important). A total of 12 items were measured, with two itemsFootnote 5 for each justification.

How important is the following justification in determining the penalty for the defendant in this case?

To even out the wrong that the offender had done (retribution)

To atone for the perpetrator’s guilt (retribution)

So that the offender cannot be dangerous to others (incapacitation)

So that the population does not have to fear the perpetrator for the time being (incapacitation)

To demonstrate to the population that crime does not pay (general deterrence)

To deter others from committing similar offenses (general deterrence)

To allow the rehabilitation of the offender (rehabilitation)

To allow the offender to be educated according to our legal system (rehabilitation)

To deter the offender from further offenses (deterrence of the offender)

So that the offender knows that crime does not remain unpunished (deterrence of the offender)

To confirm the values that are important in society (positive general prevention)

So that people’s trust in the legal system is not reduced (positive general prevention)

The order of presentation of the 12 items was randomized for each participant.

Sentencing decisions

After the participants responded to the two justification scales (four justifications on the numerical input, six justifications on Likert), they were asked about the sentence and entered the number of years of imprisonment. The upper limit was 30 years, as it is the maximum prison term in Japan.

The prosecutor asked for a prison sentence of 16 years for the defendant in this case. Do you think the sentence should be longer than that? Do you think it should be shorter? Write down the number of years that you intuitively think are appropriate; please answer in the range of 1 to 30 years.

Results

Differences in justification

We compared judges with laypeople in terms of the numerical input scale of justification, in which the total of the four justifications (retribution, incapacitation, general deterrence, and rehabilitation) was equal to 100%. This scale was originally developed to measure the relative importance of justification based on previous research that theorized that sentencing justification is a hybrid of the four types of justification (Robinson 1987). The results of analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated little difference in the relative proportion of importance of each justification between judges and the laypeople (F (3,735) = 0.33, p = 0.79; partial ηp2 = 0.00; Table 1). Both judges and laypeople placed higher importance on retribution than others (ps = 0.00). The other three justifications were given about the same proportion (ps > 0.15) and were almost equally divided.

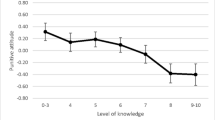

In addition to the numerical input method, we also measured justification using a Likert scale (Orth 2003) to measure the “absolute” importance of each item. In this scale, two justifications (deterrence of the offender and positive general prevention) were added because they were used along with the original four in the previous study and were conceptually relevant to the original four. The mean value of the total score (0 to 10) for each justification is illustrated in Fig. 1. In marked contrast to the measurement of relative importance, the results indicate that judges gave less importance to all the justifications than the laypeople. In particular, for incapacitation (t(245) = 4.15, p < 0.001, Hedge’s g = 0.67), general deterrence (t(245) = 3.07, p = 0.002, Hedge’s g = 0.49), and rehabilitation (t(245) = 3.51, p < 0.001, Hedge’s g = 0.56), the differences were striking. Judges also tended to place slightly less importance on retribution (t(245) = 1.65, p = 0.010, Hedge’s g = 0.26). Regarding deterrence of the offender and positive general prevention, which were included only in the Likert scale, judges placed less importance on them, and the differences were marginally significant (p = 0.13 and p = 0.07, respectively).

Differences in sentencing decisions

At this juncture, the following question becomes relevant: Was there a difference in sentencing decisions? The last part of the questionnaire asked the participants what prison sentence should be given to the defendant (they were not given the choices of the death penalty or life imprisonment). The mean number of years deemed appropriate by judges and laypeople is illustrated in Fig. 2. Despite the prosecutor-suggested sentence of 16 years for both groups, the number of years chosen by judges was significantly shorter than that by laypeople (14.4 vs. 16.9 years, t(245) = 2.50, p = 0.013, Hedge’s g = 0.40).

However, there were differences in gender and age composition between the judges and laypeople in this study. Regarding gender, the laypeople sample was almost evenly divided between men and women, whereas the number of female judges was very low (six out of 48). The judges were also about 5 years older than the laypeople on average. To control for these minor effects of gender and age, we performed a covariance analysis with the objective variable being prison term and the explanatory variables being occupation, gender, and age and confirmed that the adjusted prison term was significantly shorter for judges than for laypeople (Table 2).

To test the possibility that differences in sentencing decisions by occupation were mediated by justification, we conducted a path analysis using justification scores as measured by the Likert scale (Orth 2003). First, we drew a path that represents the assumption of this study: the emphasis on justifications differs depending on the occupation. Second, based on the theoretical framework of a previous study (Carlsmith 2006), we drew a path to indicate the effect of justification on the severity of the sentence. Findings indicated that the three justifications (incapacitation, general deterrence, and rehabilitation) that judges did not place less importance on compared to the laypeople, had an indirect effect on sentence length. Moreover, the profession of the judge reduced the importance of these three justifications, resulting in sentencing differences (Fig. 3).

Discussion

We conducted a quasi-experiment on a murder case to compare the justification and results of sentencing decisions between judges and laypeople. Few attempts have been made to examine the justifications and sentencing decisions of judges in comparison to those of laypeople using the same case as the experimental material. The case in the current study was one type of murder that often occurs in Japan, wherein the judge and the lay judge discuss and decide the sentence. The material was prepared by referring to real sentences, so it contained almost all the information necessary to make a sentencing decision. Thus, by giving equal and sufficient information about a typical case, we explored the baseline differences between judges and laypeople.

Justification

The scale—in which the participants were asked to enter a numerical value for retribution, incapacitation, general deterrence, and rehabilitation so that they totaled 100%—was developed to measure the relative importance of justifications, based on previous research that posits four hybrids (Robinson 1987). In the comparisons using this scale, there was little difference between judges and laypeople in the relative importance of each justification. It might be a matter of problems with the new scale, such as difficulty in addition. When asked to evaluate each justification’s importance on the same Likert scale of the previous study (Orth 2003), judges did not place as much importance on rehabilitation, incapacitation, or general deterrence as laypeople. These differences suggest that judges are more dispassionate in their view that the punishment itself has no significant utilitarian effect. The results of the path analysis suggested that differences in justification were reflected in sentencing decisions. Laypeople emphasized all utilitarian justifications, which means that when judges and laypeople discuss sentencing, the latter may argue that sentencing should be justified to deter crime for all reasons, whereas the former are not too keen on their argument. As previous studies (Eisenberg et al. 2005; Hastie 2000) have suggested, such differences in justification can lead to disagreements in sentencing decisions between judges and laypeople. Moreover, the present study reveals that the differences are quite extensive. Therefore, for judges and laypeople to reach an agreement, they need to examine each other’s arguments from various angles.

Another interesting difference is with previous studies. Judges in our study placed less importance on both general deterrence and incapacitation. However, Warner et al. (2019) found that general deterrence and incapacitation were the most important justifications given by judges for serious crimes, with general deterrence and incapacitation ranking first and second, respectively, and retribution ranking third. What are the reasons for the differences between their results and the current study? Some procedural differences may have led to the discrepancy. Warner et al. (2019) collected data on judge’s justification by coding the sentences of various serious crimes. By contrast, the present study asked judges to read the sentences of a single murder case with detail descriptions that would help them decide the sentence, including the circumstances and background of the crime, the time of the murder, and the defendant’s attitude after the crime, and then respond directly to the questionnaire. It would have influenced the judge’s thinking, and their responses would have been specific. Moreover, the current study was conducted online anonymously. Warner et al. (2019) collected non-anonymous judge’s opinions on serious crimes in general. According to the idealistic punishment theory of serious crimes (Corlett 2010; Harada 2008), judge’s judgment should be balanced, considering the possibility of the defendant’s rehabilitation and the impact of the punishment on society whether judges personally believe that the punishment has a utilitarian effect. In our study, by contrast, their anonymity may have made it easier for judges to answer in a way that emphasized their personal opinions rather than in an exemplary manner. The difference from the previous study is most likely due to these procedural differences, but it could also be due to variations among countries and judicial systems.

Sentencing decisions

In this study, the judges gave the defendant a sentence they deemed appropriate that was more than 2 years shorter than that of laypeople (14.4 vs. 16.9 years, respectively). This result was consistent with the theoretical prediction of the sentencing frame theory (Harada 2006), which states that judges familiar with two parameters of sentencing, impose lighter sentences. These results are almost identical to those of the previous study (Training and Research Institute for Court Officials 2007), in which the judges sentenced the accused to lighter sentences than the laypeople. However, while our study was consistent with the previous study on length of prison sentence, it yielded different results on SD. In the previous study, the SD of the sentences of judges was about half that of the laypeople; however, in this study, there was little difference between the two (6.0 years vs. 6.3 years, Fig. 2). In the previous study, no sentences were requested and only a short vignette was used, so the decisions were all left to the participant’s own perception of the murder case. Naturally, judges who could rely on the precedents had shorter sentences and smaller SDs than laypeople. In the present study, however, the sentence was indicated as 16 years imprisonment, and all the information necessary to decide the sentence was detailed. Both the judges and laypeople may have used 16 years as a cue (i.e., the anchoring effect; Watamura et al. 2014) and considered the detailed information equally, so the SD was similar.

Implications and limitations

The present study suggests that judges are more skeptical of the utilitarian effects of punishment than laypeople. As discussed earlier, this difference can lead to major disagreements between judges and laypeople. Furthermore, it may have a social impact beyond the courtroom. Laypeople tend to trust judges only when they feel that the latter makes reasonable judgments and impose appropriate penalties; they then recognize the judiciary’s fairness and effectiveness (Tyler and Boeckmann 1997). The less emphasis on justifications on the part of judges could give laypeople the impression that they envisage crimes in a different way than laypeople do, thereby possibly undermining laypeople’s will to follow the law. However, it is more likely that judges do not give much consideration to justification and use different standards than the average person in determining sentences. Conforming to past decisions and precedents may be one such criterion. The prison sentences that the judges considered appropriate was 14.4 years, while in the murder case that served as the model for this study, the defendant was sentenced to 14 years in prison. It means that (even though the SD was large,) the judge’s’ answer, on average, was close to the “correct” answer. It was suggested that judges could arrive at the “correct” answer by these criteria even under the condition that they were given the same information as laypeople.

This study, which identified differences between judges and laypeople for a single case, had several limitations. First, this study was a quasi-experiment in which participants were not randomly grouped. In addition to the occupational difference of being a judge or not, various other factors, such as sense of justice and critical thinking, could have influenced the results. Second, the experimental material for this study was a murder case caused by a financial dispute and was not a case in which opinions were easily divided. The result might have been different if the case had involved a sex crime or abusive death, both of which are abhorrent for laypeople who would be more likely to be more punitive. On the contrary, laypeople may be sympathetic to the accused in the case of a caregiver’s murder. As judges must be impartial in such cases, the differences between them and the laypeople may be more pronounced. Third, the numerical input scale was not effective in “common” cases where any justification is not extremely endorsed. In fact, both judges and lay people rated the retribution as 33.0%, and no difference could be detected. However, we expect that the differences between the groups will be more pronounced for the cases where some justification is more likely to be emphasized, such as sex crimes and abusive deaths. However, since the Likert scale (Orth 2003) provides an absolute rating, it is likely that judges scored lower and, as a result, differed from lay people. Fourth, we recruited judges from samples registered with an internet survey company, but the sample was small and difficult to collect. The sample that we managed to recruit was skewed in terms of age and the proportion of gender. An analysis of covariance showed that even controlling for the effects of age and gender, there were differences from the laypeople sample, but a larger sample size would have made the findings more compelling. Lastly, there is a need to reexamine justifications other than the four used in this study. Although retribution, incapacitation, general deterrence, and rehabilitation have been commonly used in most previous studies, differences may occur for justifications other than these four aspects, as the results demonstrate that laypeople place more emphasis on denunciation (Warner et al. 2019). Restoration is very a different kind of justice than “justice achieved by punishing criminals” (Gromet and Darley 2009), which makes it an interesting element to compare between judges and laypeople. Finally, some cultural characteristics might have influenced the results. While Japan’s judicial system is almost identical to the lay judge system of European countries, its religious belief, view of life and death, and attitudes toward norms may also influence sentencing decisions. A global discussion of the differences between judges and laypeople would require an international comparison based on a method that removes the influence of these characteristics.

Data availability

Questions, data, and experimental material (text on the case) are available in the Open Science Framework or as supplementary material.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

The new Model Penal Code “purposes” section is significantly different. It now sets the primary distributive principle for criminal liability and punishment to desert that is, the blameworthiness of the offender. Alternative distributive principles such as deterrence, incapacitation, or rehabilitation may be pursued only to the extent that they remain within the bounds of desert (Robinson et al. 2010, p. 1944).

Standard Deviation.

Although two items each may not be enough, we decided to use the same items as in the previous study (Orth 2003).

References

Bentham J (1843) The works of Jeremy Bentham (Vol 1). William Tait, Edinburgh

Berryessa CM (2018) The effects of psychiatric and “biological” labels on lay sentencing and punishment decisions. J Exp Criminol 14:241–256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-018-9322-x

Brubacher MR (2018) Third-party support for retribution, rehabilitation, and giving an offender a clean slate. Psychol Public Policy Law 24:503–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000179

Carlsmith KM (2006) The roles of retribution and utility in determining punishment. J Exp Soc Psychol 42:437–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.06.007

Carlsmith KM (2008) On justifying punishment: the discrepancy between words and actions. Soc Justice Res 21:119–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-008-0068-x

Carlsmith KM, Darley JM, Robinson PH (2002) Why do we punish? Deterrence and just deserts as motives for punishment. J Pers Soc Psychol 83:284–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.2.284

Corlett JA (2010) Punishment and ethics: new perspectives. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke

Crow MS, Bales W (2006) Sentencing Guidelines and focal concerns: the effect of sentencing policy as a practical constraint on sentencing decisions. Am J Crim Justice 30:285–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02885896

Crow MS, Gertz M (2008) Sentencing policy and disparity: guidelines and the influence of legal and democratic subcultures. J Crim Justice 36:362–371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2008.06.004

Eisenberg T, Heise M (2011) Judge-jury difference in punitive damages awards: who listens to the Supreme Court? J Empir Leg Stud 8:325–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-1461.2011.01211.x

Eisenberg T, Hannaford-Agor PL, Hans VP, Waters NL, Munsterman GT, Schwab SJ, Wells MT (2005) Judge-jury agreement in criminal cases: a partial replication of Kalven and Zeisel’s The American Jury. J Empir Leg Stud 2:171–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-1461.2005.00035.x

Eisenberg T, Hannaford-Agor PL, Heise M, LaFountain N, Munsterman GT, Ostrom B, Wells MT (2006) Juries, judges, and punitive damages: empirical analyses using the Civil Justice Survey of State Courts 1992, 1996, and 2001 data. J Empir Leg Stud 3:263–295. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-1461.2006.00070.x

Englich B, Mussweiler T, Strack F (2006) Playing dice with criminal sentences: the influence of irrelevant anchors on expert’s judicial decision-making. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 32:188–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205282152

Fukushima Y, Mukai T, Aizawa I, Iriama S (2021) Judges’ evaluation of psychological FINDINGS: EMPIRICAL research on criminal judgment. Jpn J Psychol 92:278–286. https://doi.org/10.4992/jjpsy.92.20212

Gottlieb A (2017) The effect of message frames on public attitudes toward criminal justice reform for nonviolent offenses. Crime Delinq 63:636–656. https://doi.org/10.1177/F0011128716687758

Graham J, Nosek BA, Haidt J, Iyer R, Koleva S, Ditto PH (2011) Mapping the moral domain. J Pers Soc Psychol 101:366–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021847

Gromet DM, Darley JM (2009) Punishment and beyond: achieving justice through the satisfaction of multiple goals. Law Soc Rev 43:1–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5893.2009.00365.x

Guthrie C, Rachlinski JJ, Wistrich AJ (2007) Blinking on the bench: How judges decide cases. Cornell Law Rev 93:1

Harada K (2006) Hoteikei-no-henkou-to-ryoukeinituite. Changes in statutory penalties and sentencing. Keihouzasshi 46:32–42

Harada K (2008) The practice of sentencing, 3rd edn. Tachibana Syobo, Tokyo

Hastie R (2000) Emotions in juror’s decisions. Brooklyn Law Rev 66:991

Japan Federation of Bar Associations (2020) White Paper on Attorneys 2020. https://www.nichibenren.or.jp/library/en/about/data/WhitePaper2020.pdf. Accessed 19 Dec 2021

Kanai R (2012) Dotoku Kiban Shakudo [Moral Foundations Questionnaire]. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1UflzHkc8g5ohW_MIKGzbrGH5bIPiJoWcSvfuq7OsoYc/edit#gid=39. Accessed 20 Feb 2021

Kant I (1952) The science of right. (Hastie W, Trans). In Hutchins R (ed) Great books of the Western world. T & T Clark (original work published 1790), pp 397–446

Keller LB, Oswald ME, Stucki I, Gollwitzer M (2010) A closer look at an eye for an eye: Layperson’s punishment decisions are primarily driven by retributive motives. Soc Justice Res 23:99–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-010-0113-4

Mastumoto T (2006) Keijisaibankan-ra-no-ryoukeikankaku-to-ryoukeikijyun-no-keisei [Criminal judges’ sense of sentencing and the formation of sentencing standards]. Keihouzasshi 46:1–17

McFatter RM (1978) Sentencing strategies and justice: effects of punishment philosophy on sentencing decisions. J Pers Soc Psychol 36:1490–1500. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.36.12.1490

Ministry of Justice (2018) White paper on crime 2018. https://hakusyo1.moj.go.jp/jp/65/nfm/mokuji.html. Accessed 19 Dec 2021

Orth U (2003) Punishment goals of crime victims. Law Hum Behav 27:173–186. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022547213760

Oswald ME, Hupfeld J, Klug SC, Gabriel U (2002) Lay-perspectives on criminal deviance, goals of punishment, and punitivity. Soc Justice Res 15:85–98. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1019928721720

Rachlinski JJ, Wistrich AJ (2017) Judging the judiciary by the numbers: empirical research on judges. Annu Rev Law Soc Sci 13:203–229. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110615-085032

Ramseyer JM, Rasmusen EB (2001) Why is the Japanese conviction rate so high? J Leg Stud 30:53–88. https://doi.org/10.1086/468111

Robinson PH (1987) Hybrid principles for the distribution of criminal sanctions. Univ Pennsylvania Carey Law Sch 82:19. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/621

Robinson PH, Goodwin GP, Reisig MD (2010) The disutility of injustice. N Y Univ Law Rev 85:1940–2033

Rucker DD, Polifroni M, Tetlock PE, Scott AL (2004) On the assignment of punishment: the impact of general-societal threat and the moderating role of severity. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 30:673–684. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203262849

Spiranovic CA, Roberts LD, Indermaur D, Warner K, Gelb K, Mackenzie G (2012) Public preferences for sentencing purposes: what difference does offender age, criminal history, and offence type make? Criminol Crim Justice 12:289–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895811431847

Spohn C (2009) How do judges decide? The search for fairness and justice in punishment. SAGE, London. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452275048.n3

Sporer SL, Goodman-Delahunty J (2009) Disparities in sentencing decisions. In: Oswald ME, Bieneck S, Hupfeld-Heinemann J (eds) Social psychology of punishment of crime. Wiley, New York, pp 379–401

Statistics Bureau of Japan (2020) Population Census. https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/kokusei/2020/summary.html. Accessed 19 Dec 2021

Steffensmeier D, Demuth S (2001) Ethnicity and judges’ sentencing decisions: Hispanic–Black–White comparisons. Criminology 39:145–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2001.tb00919.x

Training and Research Institute for Court Officials (2007) A study on public and judge’s attitudes toward sentencing—a case of murder. Training and Research Institute for Court Officials, Hosokai

Twardawski M, Tang KT, Hilbig BE (2020) Is it all about retribution? The flexibility of punishment goals. Soc Justice Res 33:195–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-020-00352-x

Tyler TR, Boeckmann RJ (1997) Three strikes and you are out, but why? The psychology of public support for punishing rule breakers. Law Soc Rev 31:237–265. https://doi.org/10.2307/3053926

Vardsveen TC, Wiener RL (2021) Public support for sentencing reform: a policy-capturing experiment. J Exp Psychol Appl 27:430–446. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000339

Vidmar N, Miller DT (1980) Social psychological processes underlying attitudes toward legal punishment. Law Soc Rev 14:565–602. https://doi.org/10.2307/3053193

Warner K, Davis J, Spiranovic C, Cockburn H, Freiberg A (2019) Why sentence? Comparing the views of jurors, judges, and the legislature on the purposes of sentencing in Victoria, Australia. Criminol Crim Justice 19:26–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895817738557

Watamura E, Wakebe T, Maeda T (2011) Can jurors free themselves from retributive objectives? Psychol Stud 56:232–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-011-0079-9

Watamura E, Wakebe T, Saeki M (2014) Experimental verification of the anchoring effect of a punishment reference histogram. Jpn J Soc Psychol 30:11–20. https://doi.org/10.14966/jssp.30.1_11

Weiner B, Graham S, Reyna C (1997) An attributional examination of retributive versus utilitarian philosophies of punishment. Soc Justice Res 10:431–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02683293

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mr. Ryu Ishii, chief public prosecutor, for his helpful discussions and suggestions on the manuscript.

Funding

This research was facilitated by grants from JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number 19K14358).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

WE led the study and conducted the experiments. WT reviewed the research plan and participated in writing the paper. IT analyzed the data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare relevant to the content of this article.

Ethical approval

The questionnaire and methodology for this study were approved by the Ethical Review Committee for Behavioral Sciences, Graduate School of Human Sciences, Osaka University (Ethics approval number: HB020-023).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

The participants consented to the submission of this report to the journal.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Watamura, E., Wakebe, T. & Ioku, T. A comparison of sentencing decisions and their justification between professional judges and laypeople in Japan. SN Soc Sci 2, 48 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00353-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-022-00353-4