Abstract

Despite prevailing scientific evidence to the contrary, gender stereotypes of emotion maintain that females are more emotional than males. Although inaccurate gender stereotypes of emotions abound, the extent to which young women are influenced by emotion stereotypes is unknown. The current study examines if exposure to stereotype messages about expressing emotions, and the consequences of expressing such emotions, affects young women’s experience and expression of emotions. Using an experimental design, young women were randomly assigned to hear (and read) one of four messages directly or indirectly describing females’ emotional experiences and expressions relative to males’, and the negative or positive consequences of such experiences and expressions. Participants then reported their willingness to express emotions via the 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Watson et al. in J Personal Soc Psychol 54(6):1063–1070, 1988. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063) and engaged in an “Emotion-Recollection Task” (Hess et al. in Cognit Emot 14(5):609–642, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930050117648; Weinstein and Hodgins in Personal Soc Psychol Bull 35(3):351–364, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208328165) where they described, in writing, a recent emotional life event. Results revealed that participants were more comfortable expressing negative emotions, and demonstrated a greater willingness to actually express their emotions, when exposed to direct rather than indirect stereotyped messages. Although the young women did not report feeling more comfortable expressing their emotions following emotion-related stereotypes with positive or negative consequences, they did in fact use more emotion words when a stereotype message reflected positive rather than negative consequences. The study demonstrates how emotion-related stereotypes may affect the lived experience of young women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The pervasive belief that females are more emotional than males,Footnote 1 despite scientific evidence that gender differences in emotional experiences and expressions are exaggerated (Barrett and Bliss-Moreau 2009; Else-Quest et al. 2012; Plant et al. 2000; Shields 2013), is curious and concerning. Consistent with social role theory of emotions (Eagly et al. 2000; Fiske et al. 2002), beliefs about the differences between males’ and females’ emotional experiences and expressions appear to “tell us more about [American] cultural stereotypes than about actual sex [or gender] differences in emotions” (Fischer 1993, p. 312). Regardless of the accuracy of perceived gender differences in emotional experiences and expressions, exposure to emotion-related stereotypes is, particularly for young women, quite pernicious (Shields 2013).

Young women’s exposure to emotion-related stereotypes leads to many non-trivial negative outcomes, such as social and economic penalties (Salerno et al. 2019; Smith et al. 2016), internal attributions of failure (Barrett and Bliss-Moreau 2009), and altered identities or career paths (Brescoll 2016). Despite the well-documented negative effects of emotion-related stereotypes, research on the extent to which young women’s emotional experiences and expressions are influenced by exposure to emotion stereotypes has yet to be examined. Because young women experience heightened awareness of and tendency to conform to prescriptive norms for gender stereotypes during adolescence and young adulthood (Hill and Lynch 1983; Klaczynski et al. 2020), while also increasing their expression of emotions during these developmental periods (Chaplin 2015; Chaplin and Aldao 2013; Hill and Lynch 1983), it is likely that young women’s exposure to gender stereotypes about emotions (and the positive or negative social consequences associated with the emotions) affects their experiences and expressions of emotions. Such a concern is warranted, because individuals are motivated to regulate their feelings in response to situations that present a threat, such as exposure to negative emotion-related stereotypes (see literature on stereotype threat and appraisal-based theories of stress; Avero et al. 2003); therefore, it is important to examine if young women’s emotional experiences and expressions are affected by these stereotypes. The current study examines the effects that exposure to (direct or indirect) stereotype messages about emotions, and the consequences of expressing emotions, have on young women’s perceived comfort in expressing and actual willingness to express their emotions.

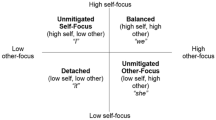

Social role theory and the promotion of emotion-related stereotypes

Gender stereotypes reflect a set of shared beliefs and expectations about the perceived and prescribed characteristics of men and women (Fiske and Stevens 1993). Gender stereotypes about emotion specifically, then, reflect shared beliefs about and expectations for how men and women should experience and express emotions (Fischer 1993). Social role theory of emotion (Brescoll 2016; Eagly et al. 2000; Fiske et al. 2002) describes that gender differences in emotional experiences and expressions are largely culturally constructed and used to reinforce social role expectations which, unfortunately, in American culture, are used to “justify the disadvantaged position of women in society” relative to men (de Lemus et al. 2013, p. 109).

Scientific knowledge of widely held gender stereotypes for men’s and women’s emotional experiences and expressions is derived from studies asking adults (and children) about their expectations for the emotional experiences and expressions of men and women (Chaplin and Aldao 2013; Robinson et al. 1998; Shields 2002) and, to some extent, studies asking individuals about their own emotional experiences and expressions (e.g., Cox et al. 2000; Grossman and Wood 1993). Results predominantly reveal that women are generally perceived as, and expected to be, more emotional than men (Heesacker et al. 1999; Hess et al. 2000; Plant et al. 2000), leading one researcher to assert that beliefs about women’s heightened emotionality compared to men’s comprise a “master stereotype”—the notion that overgeneralizations about women’s emotionality are so deeply engrained in dominant American culture that their inaccuracy goes unrecognized and unchallenged (Shields 2002, p. 11). Consequently, consistent with social role theory of emotion, the master stereotype describing women as more emotional than men contributes to structural barriers that sustain and perpetuate women’s marginalized position in American society (e.g., women are too emotional to be good leaders), making it challenging for them to navigate if, when, and how much to experience and express emotions in their daily lives (Dolan 2014).

Despite robust evidence clearly and repeatedly documenting the stereotypic expectations for female’s emotional experiences and expressions relative to male’s, research on women’s emotional experiences and expressions without comparison to men’s emotional experiences and expressions are “few and far between” (Shields et al. 2018, p. 190). Additionally, research (particularly experimental research) has yet to examine the influence of emotion-related stereotypes on women’s perceived comfort in expressing and actual willingness to express their emotions. Consequently, it is important to examine how gender stereotypes about women’s emotional experiences and expressions uniquely affect their perceived comfort in expressing and actual willingness to express their emotions. One highly relevant literature for informing how gender stereotypes about emotion likely affect women’s emotional experiences and expressions is stereotype activation (Wheeler and Petty 2001).

Effects of stereotype activation on women

Men and women are highly aware of stereotypes for their gender (Shields et al. 2018; Zammuner 2000) and, when exposed to the stereotypes, tend to report beliefs and exhibit behaviors that are stereotype consistent (Wheeler and Petty 2001). That is, regardless of whether individuals’ exposure to stereotype content is positive or negative, activated subtly (e.g., implicitly or indirectly) or blatantly (e.g., explicitly or directly), individuals’ beliefs and behaviors tend to align with the stereotype content (Steele and Ambady 2006). For example, among previous research that has demonstrated how activation of gender stereotypes elicits stereotype-consistent beliefs and behaviors, women’s exposure to stereotyped information promoted their adoption of a submissive body posture (de Lemus et al. 2012), requests for greater dependency-oriented help (Shnabel et al. 2015), and beliefs about their adequacy for female dominated but inadequacy for male-dominated academic fields (Steele and Ambady 2006). Such results powerfully demonstrate how women’s exposure to gender stereotypes promotes their stereotype-consistent beliefs and behaviors. In addition, because numerous studies document the particularly pernicious (and oftentimes long-lasting) consequences for women’s deviations from emotion-related stereotypes (see three-study example by Brescoll and Uhlmann 2008), it is reasonable to predict (in the current study) that women’s exposure to gender stereotypes for their emotional experiences and expressions will result in stereotype-consistent beliefs and behaviors.

Despite a robust literature documenting that exposure to gender stereotypes tends to elicit stereotype-consistent beliefs and behaviors, there are reasons to believe that members of stereotyped groups may resist (or react against) stereotype content and express beliefs and behaviors that are stereotype inconsistent (de Lemus et al. 2013). For example, across three unique studies, Hopkins et al. (2007) demonstrated that individuals made aware of a negative group stereotype were motivated to refute the stereotype by engaging in counter-stereotypic behaviors. Such counter-stereotypic behaviors are thought to emerge because members of stereotyped groups are particularly aware that stereotypes over-emphasize the homogeneity and under-emphasize the heterogeneity of their group (Lee and Ottati 1995). Because members of stereotyped groups (i.e., women in the current study) are particularly cognizant of differences that exist within their group (see ideas reflecting ingroup heterogeneity in social identity theory; Lee and Ottati 1995; Mullen and Hu 1989), they may reject the overgeneralizations of their group and engage in stereotype-inconsistent behaviors. Such stereotype-inconsistent behaviors can serve as “acts of communication intended to ameliorate the [negative] position of the [stereotyped] group in an intergroup context” (Hopkins et al. 2007, p. 787). Given this literature, and in contrast to the prediction described previously, women’s exposure to gender stereotypes for their emotional experiences and expressions might result in stereotype-inconsistent attitudes and behaviors—with women reporting a reduced willingness to express, and actually expressing less, emotions.

Current study

Despite prevailing scientific evidence to the contrary, gender stereotypes of emotion maintain that females are more emotional than males (Barrett and Bliss-Moreau 2009; Else-Quest et al. 2012; Heesacker et al. 1999; Hess et al. 2000; Plant et al. 2000; Shields 2013). Although inaccurate gender stereotypes of emotions are ubiquitous, the extent to which young women are influenced by emotion stereotypes is unknown. Given opposing scientific explanations for how women might respond to stereotype messages about their emotional expressions, in the current study, it is possible that women’s exposure to gender stereotypes for their emotional experiences and expressions may result in stereotype-consistent beliefs and behaviors (i.e., express more emotion) or may result in stereotype-inconsistent beliefs and behaviors (i.e., express less emotions). The current study adds to the existing literature on women’s exposure to gender stereotypes by examining if exposure to stereotype messages about expressing emotions, and the consequences of expressing such emotions, affects women’s experience and expression of emotions.

Method

Participants

A priori power analysis, using G*Power (Faul et al. 2007), for a two-way between-subjects factorial design indicated that to find a medium effect size (f = 0.25),Footnote 2 alpha (α = 0.05), at power (0.80), a sample of N = 90 was needed. Consequently, 92 young women, ranging in age from 18 to 25 (Mage = 19.83, SD = 1.31 years), from a midsized private university in the Midwest region of the United States, participated in the study.

Materials and procedure

University IRB approval was obtained prior to conducting the present study. One female experimenter conducted the data collection sessions in English. To be included in the study, participants had to be 18 years of age or older and identify as female. At the beginning of each session, participants completed an informed consent document and were randomly assigned to hear one of four messages directly or indirectly (i.e., message directness) describing females’ emotional experiences and expressions relative to males’, and the negative or positive consequences (i.e., consequence of message) of such experiences and expressions (see Appendix). In the direct stereotype conditions, the young women learned that females are more or less emotional than males, leading to negative or positive consequences for females, respectively. In the indirect stereotype conditions, the young women learned that males are more or less emotional than females, leading to positive or negative consequences for females, respectively. To be consistent with American societal stereotypes about expressing emotion, the stereotyped messages always described that expressing more emotions leads to negative outcomes, regardless of whether the messages were direct or indirect. The participating women then reported their willingness to express emotions via the well validated and highly used 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al. 1988), by indicating the extent to which, using a scale ranging from 1 (Very Slightly or Not at All) to 5 (Extremely), they currently felt comfortable expressing each of the 10 positive (α = 0.89) and 10 negative (α = 0.87) emotions publicly. Subsequently, participants engaged in an “Emotion-Recollection Task,” where they described, in writing, a recent emotional life event. The Emotion-Recollection Task was modeled after commonly used writing paradigms whereby individuals describe their thoughts and feelings in response to some stimulus (Hess et al. 2000; Weinstein and Hodgins 2009). Participants were instructed to describe the timeline of events leading up to and following the emotional event but were not told that the nature of their recollection had to reflect a positive or negative experience. Two coders, blind to condition, independently read the essays and counted the number of emotion words used (κ = 0.93) and coded whether the essays reflected positive or negative experiences (κ = 0.89). At the end of the study, participants completed a demographic questionnaire, which included a manipulation check question, and were then fully debriefed, asked if they had any questions, and thanked for their participation. Ninety-two percent (n = 85) of participants passed the manipulation check question. Analyses reported below were conducted with and without data from participants who failed the manipulation check and results were consistent, so all data were included. Participants were compensated with “research participation credit” required in their psychology classes.

Results

Effects of the emotion-related stereotype messages on young women’s perceived comfort in expressing and actual willingness to express emotions were analyzed using 2 (Message Type) × 2 (Message Valence) between-subjects factorial analyses of variance.

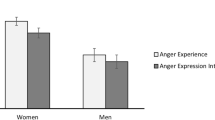

Perceived comfort in expressing emotions

The consequence of the message did not affect young women’s willingness to express positive, F(1, 88) = 1.00, p = 0.76, η2 = 0.00, or negative, F(1, 88) = 0.45, p = 0.50, η2 = 0.01, emotions. However, the young women believed they would be more comfortable expressing their negative emotions, F(1, 88) = 5.03, p = 0.03, η2 = 0.05, when the messages were direct (M = 1.94, SD = 0.68) compared to indirect (M = 1.65, SD = 0.61). No effect of message directness emerged for positive emotions, F(1, 88) = 1.13, p = 0.29, η2 = 0.01. The interactions between message directness and consequence of message on the young women’s comfort in expressing positive or negative emotions were not significant, F(1, 88) = 3.56, p = 0.06,Footnote 3η2 = 0.04 and F(1, 88) = 2.29, p = 0.13, η2 = 0.03, respectively.

Actual willingness to express emotion

The effect of message directness on young women’s actual expression of emotion approached significance, F(1, 88) = 3.30, p = 0.07, η2 = 04. The women tended to use more emotion words when the stereotype messages were direct (M = 9.04, SD = 3.77) compared to indirect (M = 8.19, SD = 2.70). Further, the young women used more emotion words when the stereotype messages yielded positive (M = 9.96, SD = 3.61) compared to negative (M = 7.44, SD = 2.52) outcomes, F(1, 88) = 16.52, p < 0.001, η2 = 16. The interaction between message directness and consequence of message was significant, F(1, 88) = 13.07, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.13, revealing no difference in the number of emotion words used in response to indirect stereotype messages, t(41) = − 0.33, p = 0.75; however, for direct stereotype messages, the young women used more emotion words when the valence of the stereotype message was positive (M = 11.59, SD = 3.72) than negative (M = 6.96, SD = 2.24), t(47) = − 5.38, p < 0.001. Because so few participants’ essays reflected positive emotional experiences (18 of 92; 19.6%), analyses examining differences in the pattern of positive versus negative emotions words used in the essays could not be conducted.

However, to examine if the stereotype messages affected whether the young women described a positive or negative emotional life experience, a three-way Chi-square analysis was conducted. No relationships emerged between message consequence and the positive or negative nature of the women’s essays for either the indirect, χ2(1) = 0.28, p = 0.60, or direct, χ2(1) = 0.30, p = 0.59, messages. The young women’s essays generally reflected negative emotional experiences (see Table 1).

Discussion

The present study examined whether exposure to stereotyped messages concerning females’ experience of emotion relative to males’ affect young women’s perceived comfort in expressing and actual willingness to express emotions. Because exposure to stereotypes can negatively affect the experiences of those stereotyped (Davies et al. 2002; Pinel and Paulin 2010) and may be particularly impactful during adolescence and young adulthood (Chaplin 2015), examining if young women are influenced by, emotion stereotypes is important. Overall, the present findings yield valuable information about the role of emotion-related stereotypes on females’ experience and expression of emotion, as well as questions that provide important directions for future research on the topic.

The young women in the current study reported they could comfortably express negative affect after exposure to direct (compared to indirect) stereotype messages about females’ emotional expressions relative to males’. In addition, the young women tended to demonstrate a greater willingness to actually express their emotions when exposed to direct rather than indirect stereotype messages. Because the direct stereotype messages described that females should not express emotion (i.e., there are negative [positive] outcomes for females who are more [less] emotional than males so females should not express emotion), the messages likely functioned to suppress the young women’s perceived freedom to experience and express emotions, thereby eliciting stereotype reactance (Mühlberger and Jonas 2019). The reactance, or fight against their thwarted freedom to express emotion, likely contributed to the young women’s greater comfort in expressing their (negative) emotions and actual willingness to express their emotions. Unfortunately, however, these results suggest that women’s potential reactance to direct stereotyped messages may be contributing to the persistence of the stereotype (see similar idea offered by Fischer and LaFrance 2015).

The current study also examined if the presumed consequences of a stereotype message about emotions affects young women’s experience and expression of emotions. Although the participants did not report feeling more comfortable expressing their emotions following emotion-related stereotypes with positive or negative consequences, they did use more emotion words when a message reflected positive rather than negative consequences, particularly for the direct stereotype message. Such results suggest that when an emotion-related stereotype about females yields direct positive consequences, the need to control one’s emotional expressions may be reduced, possibly because expressing emotion in such a situation is not appraised as threating (Avero et al. 2003; Delelis and Christophe 2016). This suggestion is warranted given previous research demonstrates that when threat of poor performance on a task is removed, females’ performance on the task is restored (Johns et al. 2008). Because the young women in the current study who read a direct stereotype message with positive consequences did not have to worry about confirming a negative stereotype, the pressure to suppress their emotional experiences was likely attenuated. Future research could specifically examine if experiences of threat—and the perceived nature of the threat—mediate the relationship between emotion-related stereotypes and women’s experience and expression of emotion.

Prior research offered competing explanations for how women might respond to stereotype messages about their emotional experiences and expressions relative to men. Some research suggested that women’s exposure to gender stereotypes for their emotional experiences and expressions may result in stereotype-consistent beliefs and behaviors (i.e., express more emotion; Wheeler and Petty 2001), whereas other research suggested women’s exposure to the gender stereotypes may result in stereotype-inconsistent beliefs and behaviors (i.e., express less emotions; de Lemus et al. 2013; Hopkins et al. 2007). Results from the current study are generally consistent with the idea that women’s exposure to gender stereotypes for their emotional experiences and expressions tends to elicit behaviors that are stereotype consistent (Steele and Ambady 2006; Wheeler and Petty 2001). That is, women in the current study reported they could comfortably express (negative) affect after exposure to direct stereotype messages, and were more likely to actually express their emotions when exposed to direct stereotype messages. Considering the master stereotype for females’ emotional experiences and expressions reflects they are perceived as, and expected to be, more emotional than males (Heesacker et al. 1999 Hess et al. 2000; Plant et al. 2000), when women in the current study expressed heightened negative affect in response to the direct stereotype, they demonstrated stereotype-consistent behaviors (i.e., expressed more emotion). Interestingly, however, it is worth noting that women’s heightened expression of negative affect is inconsistent with or counter to prevailing gender norms for females’ emotional experiences and expressions. That is, females are expected to be warm, affiliative, and nurturing (Becker et al. 2007; Fiske et al. 2007)—all positive emotion-related characteristics—and, therefore, future research could examine how the expected valence for women’s emotional experiences and expressions affects their response to gender stereotype messages about emotion.

Limitations and future directions

The present findings contribute meaningfully to the scarce literature on women’s reactions to gender stereotypes about emotions. Despite the value of studying emotion-related stereotypes on females’ experience and expression of emotions, the current study only involved young-adult women exposed to a single emotion-related stereotype. Given exposure to stereotypes in the real world is more frequent than a single incident described in a laboratory setting, future research should examine the effects of emotion-related stereotypes on women’s (and, potentially men’s) actual experience and expression of emotions across time. Because exposure to stereotypes regarding emotional expressions accumulate over time, such research may find that as individuals age, the extent to which they internalize the stereotypes (or the stereotypes become an important self-relevant evaluative domain) may affect how rigidly they abide by gender expectations for emotional experiences and expressions. Although additional research is needed on the role of emotion-related stereotypes on females’ experience and expression of emotions—particularly research utilizing control conditions whereby the consequences for emotional expressions are absent or described as equivalent for men and women—the research reported here demonstrates the importance of examining the impact of emotion-related stereotypes on the lived experiences of women.

Despite the importance of studying the impact of emotion-related stereotypes on the lived experiences of women, the current study relied on a cross-sectional sample of participants from a single private midsized university in the Midwest. Because the college students in the current study attended a private university, where the mission of the university espouses Jesuit core values—discernment, reflection, and solidarity and kinship—the student participants may not possess beliefs or characteristics reflective of the broader population, therefore, limiting the generalizability of the current findings. Because individuals educated in the Jesuit tradition are taught to ask questions that serve to dismantle systems and institutions that maintain or sustain inequality, it may be valuable for future research to examine how individuals’ core values affect their perceptions of and experiences with gender stereotypes for emotions.

Although the results of the current study are limited by its recruitment of a cross section of only female participants from a private university, the study addresses a gap in the existing literature on women’s exposure to emotion-related stereotypes and has meaningful and practical implications. Specifically, because messages about females’ heightened emotional experiences and expressions are pervasive in American society, it is important to begin identifying and challenging the deeply engrained emotion-related stereotypes that contribute to gender inequality in society. The identification and challenging of emotion stereotypes may begin to mitigate the many non-trivial negative outcomes—social and economic penalties (Salerno et al. 2019; Smith et al. 2016), internal attributions of failure (Barrett and Bliss-Moreau 2009), and altered identities or career paths (Brescoll 2016)—that have been routinely linked to young women’s exposure to emotion-related stereotypes.

Availability of data

The data generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

Consistent with American Psychological Association recommendations for bias-free language (American Psychological Association, 2021), we refer to “males” and “females” when findings describe a broad age range of individuals, whereas we refer to “women” when describing a specific group of individuals, such as the young women aged 18–25 years of age in our study.

Although the interaction between message directness and consequence of message on the young women’s comfort in expressing positive emotions approached significance, simple effects tests yielded no statistically significant differences to report or interpret. Specifically, for direct stereotype messages, no significant difference emerged for the young women’s comfort in expressing positive emotions when the consequence of the stereotype message was positive (M = 3.55, SD = 0.73) compared to negative (M = 3.19, SD = 0.81), t(47) = − 1.67, p = 0.10. In addition, for indirect stereotype messages, no significant difference emerged for the young women’s comfort in expressing positive (M = 3.06, SD = 0.86) compared to negative (M = 3.32, SD = 0.81), t(41) = 1.04, p = 0.31.

References

American Psychological Association (2021) Gender. https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/bias-free-language/gender

Avero P, Corace KM, Endler NS, Calvo MG (2003) Coping styles and threat processing. Personal Individ Differ 35(4):843–861. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00287-8

Barrett LF, Bliss-Moreau E (2009) She’s emotional. He’s having a bad day: attributional explanations for emotion stereotypes. Emotion 9(4):649–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999398379565

Becker DV, Kenrick DT, Neuberg SL, Blackwell KC, Smith DM (2007) The confounded nature of angry men and happy women. J Personal Soc Psychol 92(2):179–190. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.2.179

Brescoll VL (2016) Leading with their hearts? How gender stereotypes of emotion lead to biased evaluations of female leaders. Leadersh Q 27(3):415–428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2016.02.005

Brescoll VL, Uhlmann EL (2008) Can an angry woman get ahead? Status conferral, gender, and expression of emotion in the workplace. Psychol Sci 19(3):268–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02079.x

Brysbaert M (2019) How many participants do we have to include in properly powered experiments? A tutorial of power analysis with reference tables. J Cognit 2(1):1–38. https://doi.org/10.5334/joc.72

Chaplin TM (2015) Gender and emotion expression: a developmental contextual perspective. Emot Rev 7(1):14–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914544408

Chaplin TM, Aldao A (2013) Gender differences in emotion expression in children: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull 139(4):735–765. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030737

Cox DL, Stabb SD, Hulgus JF (2000) Anger and depression in girls and boys: a study of gender differences. Psychol Women Q 24(1):110–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb01027.x

Davies PG, Spencer SJ, Quinn DM, Gerhardstein R (2002) Consuming images: how television commercials that elicit stereotype threat can restrain women academically and professionally. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 28(12):1615–1628. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616702237644

de Lemus S, Spears R, Moya M (2012) The power of a smile to move you: complementary submissiveness in women’s posture as a function of gender salience and facial expression. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 38(11):1480–1494. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212454178

de Lemus S, Spears R, Bukowski M, Moya M, Lupiáñez J (2013) Reversing implicit gender stereotype activation as a function of exposure to traditional gender roles. Soc Psychol 44(2):109–116. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000140

Delelis G, Christophe V (2016) Motives for the acceptance of the social sharing of positive and negative emotions and perceived motives of the narrator for sharing the emotional episode. Int Rev Soc Psychol 29(1):99–104. https://doi.org/10.5334/irsp.4

Dolan K (2014) Gender stereotypes, candidate evaluations, and voting for women candidates: what really matters? Polit Res Q 67(1):96–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912913487949

Eagly AH, Wood W, Diekman AH (2000) Social role theory of sex differences and similarities: a current appraisal. In: Eckes T, Trautner HM (eds) The developmental social psychology of gender. Erlbaum, Mahwah, pp 123–174

Else-Quest NM, Higgins A, Allison C, Morton LC (2012) Gender differences in self-conscious emotional experience: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 138(5):947–981. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027930

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A (2007) G* Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39(2):175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Fischer AH (1993) Sex differences in emotionality: fact or stereotype? Fem Psychol 3(3):303–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1997.tb02448.x

Fischer A, LaFrance M (2015) What drives the smile and the tear: why women are more emotionally expressive than men. Emot Rev 7(1):22–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914544406

Fiske ST, Stevens LE (1993) What’s so special about sex? Gender stereotyping and discrimination. In: Oskamp S, Constanzo M (eds) Claremont symposium on applied social psychology. Vol 6: gender issues in contemporary society, vol 6. SAGE, Newbury Park, pp 173–196

Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Glick P, Xu J (2002) A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J Personal Soc Psychol 82:878–902. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.6.878

Fiske ST, Cuddy AJ, Glick P (2007) Universal dimensions of social cognition: warmth and competence. Trends Cogn Sci 11(2):77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005

Grossman M, Wood W (1993) Sex differences in intensity of emotional experience: a social role interpretation. J Personal Soc Psychol 65(5):1010–1022. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.5.1010

Heesacker M, Wester SR, Vogel DL, Wentzel JT, Mejia-Millan CM, Goodholm CR Jr (1999) Gender-based emotional stereotyping. J Couns Psychol 46(4):483–495. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.46.4.483

Hess U, Senécal S, Kirouac G, Herrera P, Philippot P, Kleck RE (2000) Emotional expressivity in men and women: stereotypes and self-perceptions. Cogn Emot 14(5):609–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930050117648

Hill JP, Lynch ME (1983) The intensification of gender-related role expectations during early adolescence. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Petersen AC (eds) Girls at puberty. Springer, Boston, pp 201–228

Hopkins N, Reicher S, Harrison K, Cassidy C, Bull R, Levine M (2007) Helping to improve the group stereotype: on the strategic dimension of prosocial behavior. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 33(6):776–788. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207301023

Johns M, Inzlicht M, Schmader T (2008) Stereotype threat and executive resource depletion: examining the influence of emotion regulation. J Exp Psychol Gen 137(4):691–705. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013834

Klaczynski PA, Felmban WS, Kole J (2020) Gender intensification and gender generalization biases in pre-adolescents, adolescents, and emerging adults. Br J Dev Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjdp.12326

Lee YT, Ottati V (1995) Perceived in-group homogeneity as a function of group membership salience and stereotype threat. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 21(6):610–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295216007

Mühlberger C, Jonas E (2019) Reactance theory. In: Sassenberg K, Vliek M (eds) Social psychology in action. Springer, Berlin, pp 79–94

Mullen B, Hu LT (1989) Perceptions of ingroup and outgroup variability: a meta-analytic integration. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 10(3):233–252. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp1003_3

Perugini M, Gallucci M, Costantini G (2018) A practical primer to power analysis for simple experimental designs. Int Rev Soc Psychol 31(1):20–35

Pinel EC, Paulin N (2010) Stigma consciousness at work. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 27(4):345–352. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp2704_7

Plant EA, Hyde JS, Keltner D, Devine PG (2000) The gender stereotyping of emotions. Psychol Women Q 24(1):81–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb01024.x

Robinson MD, Johnson JT, Shields SA (1998) The gender heuristic and the database: factors affecting the perception of gender related differences in the experience and display of emotions. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 20(3):206–219. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp2003_3

Salerno JM, Peter-Hagene LC, Jay AC (2019) Women and African Americans are less influential when they express anger during group decision making. Group Process Intergroup Relat 22(1):57–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430217702967

Shields S (2002) Speaking from the heart: gender and the social meaning. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Shields SA (2013) Gender and emotion: what we think we know, what we need to know, and why it matters. Psychol Women Q 37(4):423–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684313502312

Shields SA, MacArthur HJ, McCormick KT (2018) The gendering of emotion and the psychology of women. In: Travis CB, White JW, Rutherford A, Williams WS, Cook SL, Wyche KF (eds) APA handbook of the psychology of women: history, theory, and battlegrounds, vol 1. American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, pp 189–206

Shnabel N, Bar-Anan Y, Kende A, Bareket O, Lazar Y (2015) Help to perpetuate traditional gender roles: benevolent sexism increases engagement in dependency oriented cross-gender helping. J Personal Soc Psychol 110(1):55–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000037

Smith JS, Brescoll VL, Thomas EL (2016) Constrained by emotion: women, leadership, and expressing emotion in the workplace. In: Connerley M, Wu J (eds) Handbook on well-being of working women. International handbooks of quality-of-life. Springer, Berlin, pp 209–224

Steele JR, Ambady N (2006) “Math is Hard!” the effect of gender priming on women’s attitudes. J Exp Soc Psychol 42(4):428–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2005.06.003

Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A (1988) Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Personal Soc Psychol 54(6):1063–1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

Weinstein N, Hodgins HS (2009) The moderating role of autonomy and control on the benefits of written emotion expression. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 35(3):351–364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208328165

Wheeler SC, Petty RE (2001) The effects of stereotype activation on behavior: a review of possible mechanisms. Psychol Bull 127(6):797–826. https://doi.org/10.1037//QO33-2909.127.6.797

Zammuner VL (2000) Men’s and women’s lay theory of emotion. In: Fischer AH (ed) Gender and emotion: social psychological perspectives. Cambridge University Press, London, pp 48–70

Funding

No funding was received from any organization to support the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Consistent with the journal’s guidelines, all authors have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data; or the creation of new software used in the work; drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content; approved the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approval

Xavier University Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to data collection. All participants were required to provide informed consent.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

DePretis, R., Sonnentag, T.L., Wadian, T.W. et al. Effects of emotion-related stereotype messages on young women’s experience and expression of emotion. SN Soc Sci 1, 162 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-021-00174-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-021-00174-x