Abstract

Background

Knee arthroplasty (KA) aims to restore normal gait, correct joint alignment, improve the quality of life and activities of daily living, and provide pain relief. Hence, the main purpose of this overview was to summarise data from published reviews exploring gait changes during unaided level walking post-KA, thereby providing for recommendations for future practice and research.

Method

A systematic review of review (RoR) for articles published in English and since 2010, was conducted online using PubMed and Google Scholar, as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Metaanalyses guidelines. Predefined eligibility criteria were applied, and the data thus compiled were analysed. Study quality was assessed using AMSTAR-2 checklist.

Result

A total of 5 systematic reviews and meta-analysis consisting of 58 primary studies were included in the review. Based on the very limited evidence, it appears that though gait does not normalize post-KA, there seems to be an improvement in spatiotemporal gait parameters over mid to long term with some decline in gains over long term. Further reviews also suggest no benefits with unicompartmental KA in comparison to healthy controls or total KA patients. Further quality of the study was found to be of critically low confidence based on the AMSTAR-2 scale, suggesting that the results should be interpreted with great caution.

Conclusion

The overview highlights the knowledge gap and limitations in gait assessment research post-KA with existing heterogeneity in methods and reporting amidst other factors within primary studies, establishing the need for further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Knee arthroplasty (KA) is a popular and effective treatment for osteoarthritic knee, especially in the elderly population. KA aims to restore normal gait, correct joint alignment, improve the quality of life and activities of daily living, and provide pain relief [1, 2]. Though KA leads to improvement in functional scores it does not imply movement quality. Knowledge of joint mechanics is essential, as it has been reported that abnormal joint mechanics postoperatively may lead to wearing of implant [3, 4] and osteoarthritis progression in other joints [5]. While total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is deemed durable, unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) is associated with reduced postoperative complications and faster recovery [6, 7]. Furthermore, UKA is entrusted to restore normal gait patterns owing to the very nature of its approach to ligament preservation [8, 9]. Hence, the main purpose of this overview was to summarise data from published reviews exploring gait changes during unaided level walking post-KA, thereby providing for recommendations for future practice and research. A systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analysis [RoR] approach was opted to comprehensively synthesize and summarize the gait changes from the biomechanical perspective post-KA.

Methodology

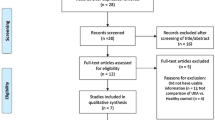

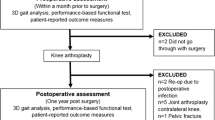

Computerized literature searches, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Fig. 1) [10], were performed for review and meta-analysis articles published in English using PubMed, and Google Scholar, over last decade (since 2010—thereby to avoid reviews involving duplication of primary studies and to synthesize current evidence). A PICO search strategy was employed.

-

Population: All reviews that investigated gait parameters while level walking in individuals who underwent KA

-

Intervention: The study group included KA patients

-

Comparison: All comparisons were considered.

-

Outcome: Gait parameter assessment or changes while level walking post KA.

Search terms used in the title, abstract, MeSH, and keywords fields included (‘gait’ [MeSH] OR ‘walking’ [MeSH] OR ‘knee’ [MeSH] OR ‘arthroplasty, knee’ [MeSH] OR ‘replacement, knee’ [MeSH] OR spatiotemporal’ [MeSH]) OR ‘review’ [MesH] OR ‘meta-analysis’ [MeSH] AND ‘gait’ [tiab] OR ‘arthroplasty’ [tiab] OR ‘walking’ [tiab] OR ‘stride’ [tiab] OR ‘cadence’ [tiab] OR ‘step’ [tiab] OR ‘ground reaction force’ [tiab] OR ‘spatiotemporal’ [tiab] ‘kinetics’ [tiab] OR ‘kinematics’ [tiab] OR ‘ambulation’ [tiab] OR ‘biomechanics’ [tiab] OR ‘review’ [tiab] OR ‘meta-analysis’ [tiab].

The bibliographies of all located articles and a forward citation search were also performed. The search was completed by 20 July 2020. Search results from each database were exported to Mendeley® (reference management software) and duplicates were removed. Further, duplicates were removed manually. Once de-duplicated, the list of available studies were screened and assessed by a single-reviewer. Ethical approval was not obtained as the study essentially was a review of previously published works. Priori defined but unpublished protocol was followed.

Scientific Merit Assessment—Methodological Quality

The scientific merit assessment was applied as an analytical instrument and was not a criterion for study exclusion. Study quality was assessed, by a single reviewer, using the A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews-2 (AMSTAR-2) tool [11], a 16 item checklist with 4 possible responses: yes, partial yes, no, or not applicable. Of the 16 items, 7 are considered “critical” domains. The reviews were rated to be of high, moderate, low, or critically low overall confidence as suggested by the tool guideline [11].

Study Eligibility

Studies were considered eligible if they fulfilled the following criteria: were systematic reviews and/or meta-analysis published in English and with full-text availability, were systematic reviews reporting gait changes post-KA reporting on kinetic, kinematic, and/or spatiotemporal aspects, and were reviews published in or after 2010.

Studies were excluded if they adhered to any of the following exclusion criteria: reviews reporting on biomechanical methodology or other than gait parameters (clinical or radiological) post-KA, reviews focussing on cadaveric studies, studies other than systematic reviews (narrative/general reviews, abstracts, case reports/series, thesis, letters, conference papers, book chapters, unpublished works, and commentaries), and duplicate publications.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Screening of all eligible publications was carried out by a single reviewer for titles, abstracts, full text, and bibliographies, utilizing predetermined criteria. In the case of multiple versions of reviews, the most current version was included, and in the case of multiple publications of identical reviews, the most detailed publication was included. Data extracted from the included reviews were entered into an Excel 2013 spreadsheet under the following headings: author(s), year of publication, review or meta-analysis, number of primary studies included, number of databases searched, search period executed, review objective, language restrictions, methodological quality assessment tool used to assess primary studies included within reviews, reporting guidelines adhered to, sample characteristics (size, demography), prosthetic used, surgery to gait analysis duration, gait measures (kinetic, kinematic and spatiotemporal), and review findings.

Data were extracted by a single reviewer from the reports and are summarised descriptively with the help of tables and graphs. In case of any missing data, no attempt was made to contact the corresponding author.

Results

Of the ten eligible studies, five reviews [12,13,14,15,16] were included in the present overview. The characteristics and findings of the included reviews are summarised in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4. Reviews that were excluded are summarised in supplemental Table 1. The included reviews included 58 primary studies, with 3.45% of primary studies included in 3 reviews, and 15.52% in 2 reviews.

A meta-analysis of RoR is a challenging task owing to the review heterogeneity, methodological variability, and overlap of primary studies within the systematic review included. Hence a narrative approach was used in the current review.

Age of the sample was reported in almost all of the studies within the reviews included, while gender distribution was inconsistently reported across studies within reviews (Table 2) with few reviews including studies done exclusively on females [12, 15]. Based on the available data, the study population was predominantly elderly and female (Table 2).

Anthropometric measures like height [12, 13], weight [12, 13] and BMI [14, 16] were scarcely and inconsistently reported across primary studies within reviews.

The number of assessments done over time varied across reviews ranged from one to four times [12,13,14,15,16], with lost to follow-up data being provided only in one review [14]. Only one review [15] reported the number of test attempts used that ranged to a maximum of eight attempts.

Patients mostly walked unaided and at their self-selected pace on a treadmill or a platform [12,13,14,15], with few studies reporting a pre-specified or varied speed [14, 15], while few failed to mention speed [14]. Further, very few studies reported the use of footwear within reviews [14, 15]. The distance walked was mentioned in two reviews [15, 16] which ranged from 4.6 to 10 m [15] in one, and 3.8 to 10 m in other [16]. Varied methods were reported across primary studies including 3D motion analysis, optoelectronic, force plate, and inertial measurement unit [12, 14]. But none of the reviews explored the effect of these factors on gait measures, due to limited study and data.

Scientific Merit Assessment of Included Reviews

All the reviews [12, 13, 15, 16], except one [14], in the present overview, received critically low confidence appraisals based on AMSTAR2 assessment, exhibiting more than one critical flaw (Fig. 2). Only one review [14] receives moderate confidence appraisal exhibiting more than one non-critical flaw. None of the reviews provided the list of excluded studies with reasoning.

Scientific Merit Assessment Within Reviews

Limitations

Various limitations were reported across the reviews which include a small number of primary studies [15, 16], observational studies [12, 13, 16], lack of healthy control group [16], lack of appropriate statistical analysis [14, 15], and studies limited to the English language [12, 14,15,16].

Further limitations included heterogeneity in regards to study design, sample characteristics, gait analysis methodology and systems, and prosthesis or implant designs [12,13,14,15]. The studies also lacked information on patient co-morbidities, and rehabilitation protocols used [16].

Discussion

The current overview was undertaken with the main objective of summarising data from published reviews exploring gait changes while unaided level walking post-KA, thereby providing for recommendations for future practice and research. Five reviews were identified with a total of 58 primary studies. Based on the very limited evidence, it appears that though gait does not normalize post-KA, there seems to be an improvement in spatiotemporal gait parameters (walking speed, cadence, and stride time) over mid to long term with some decline in gains over long term [15, 16], and also in kinematics [14]. Further reviews also suggest no benefits with UKA in comparison to healthy controls [13] or TKA patients [12].

The result of this overview highlights the knowledge gap and limitations in gait assessment research post-KA with existing heterogeneity in methods and reporting amidst other factors within primary studies, making the establishment of gait changes post-KA difficult. Further quality of the study was found to be of critically low confidence based on the AMSTAR-2 scale, suggesting that the results should be interpreted with great caution.

Though sagittal knee flexion during stance and swing phase is associated with an increased walking speed with uniform force dispersal over tibiofemoral cartilage in healthy adults [17], no significant difference [12] was found in this overview in KA patients. Further reduced muscle power, reduced quadriceps function, retained quadriceps avoidance gait, and muscular compensations postoperatively, and residual flexion deformity post arthroplasty may influence knee flexion [4, 18,19,20,21,22].

Though the research is very limited, there is some indication that KA influences joint kinematics [14]. This is important, as it has been reported that abnormal kinematics may lead to inappropriate joint loading leading to persistent symptoms and implant wear-off [3]. While no added advantage was reported for UKA in comparison to TKA [12], joint mechanics have been reported to vary based on the nature of tasks (like stair climbing) [23] and needs to be explored.

Improvement in spatiotemporal gait parameters like walking speed, cadence, and stride time was observed in the present overview [15, 16]. This is significant as walking speed is considered an indicator of good functional outcome. Even minimal improvement in walking speed to the range of 0.1 m/s has been associated with better outcomes [24, 25]. While a small decline in gains post-KA in the long term was observed in the current review, literature remains largely divided in this regards with reports of progressive functional decline [26] on one end to reports of retained functional benefits up to 15 years post-KA [27]. Aging has been associated with impaired walking speed [28], but no such finding was reported in one review comparing the effect of UKA with healthy controls [13].

The results about UKA of no benefit or advantage may be attributed to poor patient selection (degenerated or highly lax ACL) [29], and asymmetries in joint loading postoperatively in both operated and non-operated lower limb [30].

The present overview highlights gross limitation in research on the effect of various factors like implant design, surgical approach, surgical techniques, rehabilitation protocols, and patient characteristics (age gender, anthropometrics, comorbidities) [14, 15, 31] on gait. Further, there was a lack of information on KA laterality (unilateral vs. bilateral) and the effect of the operated knee on the non-operated knee and vice-versa, and also on the other joints in lower kinetic chain. This is significant as any deficiency in the operated side may lead to compensatory mechanisms in other joints of the lower kinetic chain, with reports of progression of arthritic changes in the non-operated contralateral knee in patients undergoing unilateral KA [32]. Additionally, few other factors were not considered within the reviews which may also affect the outcomes, like details of assessor/surgeon, and country of study, which may add to approach and protocol variability.

Finally, though fluoroscopy has been largely used to study the joint dynamics post-KA, various other gait assessment techniques have emerged—effects of these need to be explored from clinical and research perspective [31].

The present RoR is not without limitations. The reviews included were subjected to heterogeneity per se and due to the primary studies involved, owing to varied study objectives, diverse methodology, heterogeneous study population and setting, varied study designs, varied approaches to gait analysis, varied implant designs, and inconsistent reporting. The current RoR was a single reviewer based and involved two databases, thereby raising the possibility of reviews being missed despite a comprehensive search. Additionally, a meta-analysis could not be performed owing to study and data heterogeneity across the reviews. This RoR might be subjected to publication bias as it was limited to reviews published and in the English language. Due to the above limitations and also those outlined by individual reviews, great caution is needed to be exercised while interpreting results published across various reviews.

The result of this RoR highlights the existing gap and limitations in gait research post-KA with existing heterogeneity in methods and reporting amidst other factors. However, the review finding does signify the need for focussed rehabilitation post-KA for better outcomes achieving healthy if not normalized gait pattern limiting further damage to the operated and also other joints in the lower kinetic chain.

Way Forward

Further, appropriately powered research employing randomized control or longitudinal study design with an appropriate follow-up period, with adherence to standard reporting guidelines, and with rigorous statistical analysis exploring post-KA gait changes is required. The research needs to take in to account various factors like.

-

Assessment characteristics (assessment timing—pre and postoperatively, assessor characteristics, gait analysis—methodology, technique, and equipment),

-

Patient characteristics (age, sex, height, weight, BMI and comorbidities),

-

Surgical characteristics (type and approach of arthroplasty, prosthesis or implant type, surgical approach, laterality, surgeon characteristics),

-

Geographical characteristics (country of study—as protocols and approaches may differ),

-

Rehabilitation/gait training protocols

There is a need for consensus in regards to gait analysis, and standardization in testing methodology ensuring comparability.

Conclusions

This overview highlights the existing gap and limitations in research on the effect of KA on gait, with existing heterogeneity in methods and reporting amidst other factors. Further, there remain under-explored and unexplored research avenues, demanding the need for further high-quality research.

References

Jones, C. A., Beaupre, L. A., Johnston, D. W. C., & Suarez-Almazor, M. E. (2007). Total joint arthroplasty: Current concepts of patient outcomes after surgery. Rheumatic Diseases Clinics of North America, 33, 71–86.

Yoshida, Y., Mizner, R. L., Pamsey, D. K., & Snyder-Mackler, L. (2008). Examining outcomes from total knee arthroplasty and the relationship between quadriceps strength and knee function over time. Clinical Biomechanics, 23, 320–328.

Collier, M. B., Engh, C. A., Jr., McAuley, J. P., & Engh, G. A. (2007). Factors associated with the loss of thickness of polyethylene tibial bearings after knee arthroplasty. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume, 89, 1306–1314.

Smith, A. J., Lloyd, D. G., & Wood, D. J. (2004). Pre-surgery knee joint loading patterns during walking predict the presence and severity of anterior knee pain after total knee arthroplasty. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 22, 260–266.

Mills, K., Hunt, M. A., & Ferber, R. (2013). Biomechanical deviations during level walking associated with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken), 65, 1643–1665.

Migliorini, F., Tingart, M., Niewiera, M., Rath, B., & Eschweiler, J. (2019). Unicompartmental versus total knee arthroplasty for knee osteoarthritis. European Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery & Traumatology, 29(4), 947–955.

Hansen, E. N., Ong, K. L., Lau, E., Kurtz, S. M., & Lonner, J. H. (2019). Unicondylar knee arthroplasty has fewer complications but higher revision rates than total knee arthroplasty in a study of large United States databases. Journal of Arthroplasty, 34(8), 1617–1625.

Mir, S. M., Talebian, S., Naseri, N., & Hadian, M. R. (2014). Assessment of knee proprioception in the anterior cruciate ligament injury risk position in healthy subjects: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 26(10), 1515–1518.

Wiik, A. V., Manning, V., Strachan, R. K., Amis, A. A., & Cobb, J. P. (2013). Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty enables near normal gait at higher speeds, unlike total knee arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty, 28(9), 176–178.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., et al. (2010). PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and metaanalyses: The PRISMA statement. International Journal of Surgery, 8, 336–341.

Shea, B. J., Reeves, B. C., Wells, G., et al. (2017). AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. British Medical Journal, 358, j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008.

Nha, K. W., Shon, O. J., Kong, B. S., & Shin, Y. S. (2018). Gait comparison of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty during level walking. PLoS ONE, 13(8), e0203310. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203310.

Kim, M. K., Yoon, J. R., Yang, S. H., & Shin, Y. S. (2018). Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty fails to completely restore normal gait patterns during level walking. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 26(11), 3280–3289.

Sosdian, L., Dobson, F., Wrigley, T. V., et al. (2014). Longitudinal changes in knee kinematics and moments following knee arthroplasty: A systematic review. The Knee, 21(6), 994–1008.

Fiorentini, R., Maggioni, S., Restelli, M., Ferrante, S., & Monticone, M. (2013). Modifications of spatial-temporal parameters during gait after total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review. Italian Journal of Physiotherapy., 3(2), 55–63.

Abbasi-Bafghi, H., Fallah-Yakhdani, H. R., Meijer, O. G., et al. (2012). The effects of knee arthroplasty on walking speed: A meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 13, 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-13-66.

Hanlon, M., & Anderson, R. (2006). Prediction methods to account for the effect of gait speed on lower limb angular kinematics. Gait Posture, 24(3), 280–287.

Choy, W. S., Kim, H. Y., Kim, K. J., & Kam, B. S. (2007). A comparison of gait analysis after total knee arthroplasty and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in the same patient. Journal of Korean Orthopaedic Association, 42(4), 505–514.

Benedetti, M. G., Catani, F., Bilotta, T. W., Marcacci, M., Mariani, E., & Giannini, S. (2003). Muscle activation pattern and gait biomechanics after total knee replacement. Clinical Biomechanics, 18, 871–876.

Chassin, E. P., Mikosz, R. P., Andriacchi, T. P., & Rosenberg, A. G. (1996). Functional analysis of cemented medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty, 11(5), 553–559.

Bade, M. J., Kohrt, W. M., & Stevens-Lapsley, J. E. (2010). Outcomes before and after total knee arthroplasty compared to healthy adults. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 40(9), 559–567.

Barker, K. L., Jenkins, C., Pandit, H., & Murray, D. (2012). Muscle power and function two years after unicompartmental knee replacement. The Knee, 19(4), 360–364.

Mundermann, A., Dyrby, C. O., Hurwitz, D. E., Sharma, L., & Andriacchi, T. P. (2004). Potential strategies to reduce medial compartment loading in patients with knee osteoarthritis of varying severity: Reduced walking speed. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 50(4), 1172–1178.

Studenski, S., Perera, S., Patel, K., et al. (2011). Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA, 305(1), 50–58.

White, D. K., Felson, D. T., Niu, J., Nevitt, M. C., Lewis, C. E., Torner, J. C., & Neogi, T. (2011). Reasons for functional decline despite reductions in knee pain: The multicenter osteoarthritis study. Physical Therapy, 91(12), 1849–1856.

Gandhi, R., Dhotar, H., Razak, F., Tso, P., Davey, J. R., & Mahomed, N. N. (2010). Predicting the longer term outcomes of total knee arthroplasty. The Knee, 17(1), 15–18.

Newman, J., Pydisetty, R. V., & Ackroyd, C. (2009). Unicompartmental or total knee replacement: The 15-year results of a prospective randomised controlled trial. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British Volume, 91(1), 52–57.

Heiden, T. L., Lloyd, D. G., & Ackland, T. R. (2009). Knee joint kinematics, kinetics and muscle co-contraction in knee osteoarthritis patient gait. Clinical Biomechanics (Bristol Avon), 24(10), 833–841.

Argenson, J. N., Komistek, R. D., Aubaniac, J. M., Dennis, D. A., Northcut, E. J., Anderson, D. T., & Agostini, S. (2002). In vivo determination of knee kinematics for subjects implanted with a unicompartmental arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty, 17(8), 1049–1054.

Metcalfe, A., Stewart, C., Postans, N., Barlow, D., Dodds, A., Holt, C., et al. (2013). Abnormal loading of the major joints in knee osteoarthritis and the response to knee replacement. Gait Posture, 37(1), 32–36.

Angerame, M. R., Holst, D. C., Jennings, J. M., Komistek, R. D., & Dennis, D. A. (2019). Total knee arthroplasty kinematics. Journal of Arthroplasty, 34(10), 2502–2510.

Shakoor, N., Block, J. A., Shott, S., & Case, J. P. (2002). Nonrandom evolution of end-stage osteoarthritis of the lower limbs. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 46, 3185–3189.

Funding

This review did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sector.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare in the preparation and submission of this manuscript.

Ethical standard statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by the any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study informed consent is not required.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anand Prakash, A. Knee Arthroplasty and Gait: Effect on Level Walking—An Overview. JOIO 55, 815–822 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43465-020-00342-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43465-020-00342-w