Abstract

After three unsuccessful attempts to implement an energy tax, Taiwan introduced a carbon fee system through an amendment to the Greenhouse Gas Reduction and Management Act at the end of 2020, opening a fourth window of opportunity for carbon pricing. However, this limited carbon fee illustrates that Taiwan has taken only a tiny step forward in climate governance and highlights its lock-in, high-carbon economic path. This seems infeasible without the exogenous pressure of the European Union’s Carbon Boundary Adjustment Mechanism. Compared with East Asia’s carbon-intensive industries in Korea, China, and Japan, Taiwan lags significantly in promoting carbon pricing. This study focuses on Taiwan’s carbon fee decision-making mechanisms, democratic processes, and structural constraints within a high-carbon economy as viewed through developmental environmentalism in the East Asian climate governance literature. This study further explores how the predicament of green transformation in high-carbon-emitting developing countries takes shape, including their climate policies, value, and industrial path dependence, and especially their authoritarian and recentralized bureaucratic decision-making mode, to explain the delay in the transformation. By examining Taiwan’s initial carbon fee decision-making, this study attempts to reinterpret developmental environmentalism, shedding light on the structural predicament arising from the internationally compulsory green transformation faced by all high-carbon-emitting manufacturing countries in Asia and globally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In response to the global climate crisis, more than 132 countries have pledged or enacted laws to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 (UNFCC 2023). On Earth Day 2021, US President Joe Biden convened the leaders of 40 countries to discuss global warming and climate change. An important consensus was reached that the international carbon tax must reach US$100 to curb carbon dioxide emissions (IMF 2023). In 2020, the European Union (EU) drafted a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) with the expectation that a carbon border tax would be imposed by 2023. The draft government of the USA’s Clean Competition Act draft government also formulated carbon border taxes (Chao 2023). Countries with carbon-intensive manufacturing industries in East Asia, such as South Korea, China, and Japan, announced carbon neutrality schedules from mid-to-late 2020 (Park et al. 2022). These three countries have already implemented carbon pricing mechanisms; however, only Taiwan was excluded.

The Taiwan Environmental Protection Administration (EPA) started to revise the “Greenhouse Gas Reduction and Management Act” (GRMA) in May 2020. It renamed it the ‘‘Climate Change Response Act” (CCRA) to engage more in carbon reduction and even carbon neutrality, but the climate policies remained conservative and sluggish. According to the second phase of the national greenhouse gas (GHG) reduction schedule approved by the Executive Yuan, the industrial sector only needs to reduce its GHG emissions by 0.22% by 2025, even though it accounts for 52% of the total national GHG emissions in 2019 (MOEA 2022). Despite criticism from various circles, including environmental groups and scholars (Shaw et al. 2020; Chou 2020), the Executive Yuan did not begin to convene ministries and committees to assess net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 until the end of 2020 (EPA 2020a, b). Comparing the announcement of carbon neutrality in 2050 by South Korea, China, and Japan, Taiwan’s president, Tsai Ing-Wen, did not declare net zero emissions in 2050 until Earth Day on April 22, 2021. However, the most crucial carbon pricing mechanism remains unclear.

The new Climate Change Response Act draft at the end of 2020, prompted the EPA to take a step and propose a “carbon fee” institution. This cannot be considered a breakthrough, even though carbon pricing failed in 2006, 2009, and 2015. This loss of three opportunity windows of the proposed “Energy Tax” is considered a crucial climate undone policy (Chou and Liou 2023). Eventually, the carbon fee was proposed but was finite rather than a carbon/energy tax, which was expected mainly by the civil society. However, it can be treated as Taiwan’s fourth opportunity window of carbon pricing. This limited progress was difficult because the economy was still locked in a high-carbon path. Even though the CCRA was passed on January 10, 2023, and the carbon fee policy is still contested until 2024, the initial stage of the fourth opportunity window of carbon pricing from 2020 to the end of 2021 is worth investigating to explore how and why the carbon limit was formed and sluggish. Therefore, this study aims to analyze how Taiwan has succumbed to climate governance delays based on the government’s decision-making process regarding carbon fees in the initial stage. It is necessary to explore the reasons behind the government’s sluggish climate policy and failure to act aggressively on carbon pricing.

2 Literature review and analytical framework

2.1 Climate governance regarding developmental environmentalism

According to the TWI 2050a, b (2018) report, for a country to successfully undergo a sustainable transition, solid political institutions must be established to maintain and strengthen the state authority, capacity, and legitimacy of the transition; otherwise, governance operations will be ineffective, which, in the long term, could lead to constellations of state fragility and transitional governance deficiencies. In addition, concerning the relationship between sustainable transition and carbon tax, research using agent-based simulation suggests that carbon tax alone may not decouple the economy from carbon emission. This involves agents’ strategies of carbon reduction or renewable energy development (Nieddu et al. 2022).

Numerous scholars and institutions, such as Martinez and Garza (2017); Sulich and Zema (2018); Droste et al. (2016); Adom et al. (2021); Larissa et al. (2020); Barbier (2020); Shulla et al. (2021); EASAC (2020); Asj’ari et al. (2018); and Friedmann et al. (2018), have defined a brown economy as a model of economic growth driven primarily by fossil fuels. This carbon-based economy is inefficient and lacks social equality. Carbon-intensive activities are the core features of brown economies; such economies emphasize economic growth and ignore negative environmental impacts and social equity. Thus, the UNDP (2015) emphasized that a brown economic model could not address social marginalization and resource depletion. It is worth noticing that a brown economy usually operates under a complex series of markets, technologies, policies, institutions, and values. It is essential to explore how the government supports a brown economy through its industrial policy, developmental ideology, carbon pricing regulations, and policymaking institutions. For the study, these viewpoints can be stretched significantly to inspect what conflicts and risks arise in transitioning from a brown economy to a green economy and how they create a structural condition to slow down or hinder climate reform and carbon pricing.

According to the IEA (2021a), carbon dioxide emissions in China, Japan, and South Korea were 10.2 billion metric tons, 1.2 billion metric tons, and 620 million metric tons, respectively, ranking first, fifth, and seventh in the world. Taiwan’s carbon dioxide emission level is 270 million metric tons, and its carbon emission per capita is 11 tons, ranking eighth among countries with a population of more than 10 million worldwide. These conditions have led to three major concerns. First, how do countries with carbon-intensive economies face the transition to green? Second, how do conflicts arise over the governance of related carbon taxes? Third, what governance characteristics should be used to alleviate sustainable transition conflicts?

Taking Singapore and South Korea as examples, Dent (2012, 2017) noted that East Asian countries face challenges related to global climate change. Despite introducing low-carbon industrial and social policies, industrial upgrades and economic development remain the primary concerns of these countries, and sustainable transition is a secondary goal. Dent continued to analyze East Asian countries from the perspective of developmental states and claimed that such countries are experiencing a form of new developmentalism. Similarly, Kawakatsu et al. (2017) surmised that the primary reason for the limitations of carbon pricing mechanisms in Japan, China, South Korea, and Taiwan was the lack of understanding of nuclear energy and fossil fuel risks in the context of climate change. In East Asian countries, strategies for implementing low-carbon policies have primarily focused on industrial development, and carbon reduction has generally been regarded as an additional benefit.

In an analysis of political and economic lobbying related to carbon taxes in China, Japan, and South Korea, Liu et al. (2011) noted that opponents have proposed that carbon taxes would weaken economic development and cause social unemployment and inequality. Taking Japan as an example, Liu et al. (2011) and Kameyama (2016) suggested that Keidanren (the Japan Business Federation), a representative of carbon-intensive industries, plays a crucial role in preventing Japan from implementing a carbon tax. During the governance period of South Korean President Lee Myung-bak, the government cooperated with chaebols to vigorously promote green energy and green industries as part of a Korean-style green growth strategy. Nonetheless, the decision-making process excludes environmental organizations and ignores the maintenance of environmental and social well-being; this process is a form of environmental developmentalism (Kim 2015). Kim and Thurbon (2015) stated that the green growth strategy promoted by Lee Myung-bak’s government claimed to be one of carbon reduction but focused on the competitiveness of green and low-carbon industries; according to these authors, the strategy lacked a core climate governance framework and could be considered to constitute developmental environmentalism. These two research viewpoints, linking sustainable transition to the proposition of a developmental state, were echoed in Chang (2012) and Heo (2015). These researchers revealed that the South Korean government’s manipulation of neoliberal policies to promote its green growth policy centered on national economic competitiveness had deleterious effects on South Korea’s social welfare and labor safety systems. This type of green economy, which responds to global climate change, remains the economic prototype of a developmental state. It emphasizes the priority of green technology supporting economic development but does not truly achieve social equity and environmental sustainability. This policy is called neoliberal developmentalism.

Chou (2015, 2016) analyzed Taiwan’s sustainable development predicament and noted that the government inherited the framework of a developmental state. Although policy planning responded quickly to the United Nations Climate Summit Convention, the government continues to promote energy-intensive industries. Chou and Liou (2020) analyzed Taiwan’s brown economic model. They noted that the government instigated rent-seeking and formed damaging path dependencies, locking economic and social development at the expense of carbon reductions, environmental protection, and social equity development, severely hindering the country’s low-carbon transition. Although the government has partially planned a carbon-reduction path, shunning carbon-reduction targets and regulatory policy implementation have highlighted strong path dependence. Chou and Liou (2023) revealed that carbon-intensive industries strongly influence government decision-making. In addition to investing in fossil fuel power generation, claiming that it can provide low electricity prices to establish a techno-institutional complex, industry leaders have encouraged the Chinese National Federation of Industries (CNFI) under their control to conduct extensive political lobbying, blocking Taiwan’s three main opportunities to implement an energy tax. This carbon-intensive economic structure has formed a cognitive, institutional, and techno-institutional lock-in. Furthermore, unlike the manufacturing industries of Japan and South Korea, Taiwan’s manufacturing industry employs low-cost production (e.g., low electricity prices, water prices, and labor wages) to support a brown economy, resulting in a more robust and reinforced lock-in effect.

2.2 Recentralized bureaucracy

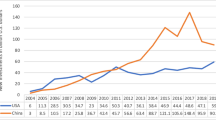

Scholars have explained that the legacy of authoritarianism in the Cold War era hindered societal transition in East Asian countries. This study mainly concerned what and how authoritarian governance by the developmental state continued to influence green transition and create structural predicaments, and thus tried to explore the characteristics of climate environmental governance. Dent (2012, 2017) proposed the concept of “new developmentalism”; in addition to highlighting that East Asian countries are committed to developing green industries and renewable energy as a new form of economic competition, he stated that developmental statism and state capacity are core factors in government decision-making and policy implementation. Dent indicated that although civil society is more politically active in East Asian countries than in other countries and is gradually gaining the ability to monitor its government, major low-carbon developmental strategies and policies are still decided in a top-down manner. Han (2015) and Kim (2015) examined the waves of democracy that began in South Korea in 1987. Environmental nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and trade unions have become the major stakeholders in climate policy. South Korea’s active democratization has allowed NGOs to participate in political decision-making, leading to the greening of society. Nevertheless, these NGOs are excluded or marginalized when making significant decisions. Han (2015) highlighted that while authoritarian environmentalism is not entirely applicable to South Korea, limited participation by NGOs and opaque decision-making caused South Korea’s greenhouse gas emissions to double from 1990 to 2007; South Korea’s emissions ranked tenth worldwide in 2012.

Taiwan’s development path is very similar to that of South Korea. Since the lifting of martial law in 1987, various democratic movements have emerged. However, Taiwan’s GHG emissions increased 1.3 times from 1990 to 2007. Chou and Liou (2012) and Chou (2015, 2016) indicated that the government made a top-down decision in 1986 to open the upstream sector of the petrochemical industry to the private sector, which accelerated the growth of carbon emissions in Taiwan from 1998, peaking in 2007. Although environmental NGOs blocked two major steel and petrochemical development projects in 1996 and 2011, these solid social movements have not changed the government’s top-down decision-making. On the contrary, the current government still prioritizes economic development by ignoring the balance between social and environmental equality and industrial growth. Kim and Thurbon (2015) used the term “developmental environmentalism” to explain the policymaking process involved in South Korea’s transition from “brown growth” to “green growth,” noting that bureaucratic elites restored the authoritarian way with superficial democracy to recentralize the decision-making of environmental governance. This study noted that the pattern, associated regulatory schema, and even culture are highly similar in South Korea and Taiwan.

Jasanoff (2005) stated that a state’s governance actions shape its regulatory culture and influence the government’s performance; in democratic nations, the patterns of policy dialogue and debate are various but at least transparent to shape their regulatory culture of policymaking. Alternative findings that address this issue can be found in East Asia. In the past two decades, scholars have conducted abundant research on the issues of rapid industrialization called “compressed modernity” in South Korea (Chang 1999, 2010) or “delayed hidden risk society” in Taiwan (Chou 2000, 2002, 2018), comparison on the governance of genetically modified organisms and stem cell research scandals in South Korea and Taiwan (Chou 2009), the Fukushima nuclear disaster in called “man-made calamities” (Funabashi 2012) even “structural disasters” (Matsumoto 2013) in Japan, and recent energy transitions in these three countries (Chou ed. 2018). They revealed that bureaucratic technocracy became the dominant policymaking model to be the legacy of developmental states in the East Asian region; that is to say, political elites with technological and economic expertise mostly dominated the development path and deliberately ignored risks, even damaging the environment, health, and social equity. This regulatory culture was firmly embedded in the decision-making processes of government agencies. Although these countries have undergone democratization, societies cannot reverse this policymaking, which involves concealment, laissez-faire risks, and even lags in risk and environmental governance. These studies pointed out that with their respective cultural and social backgrounds, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan created similar but different legacies for their developmental states.

The effects of institutional concealment can lead to environmental and technological injustices and risks. The EEA (2002) indicates that institutional ignorance eventually influences societal ignorance of risks and inequality. This study proposes that the policymaking model and the regulatory culture of hidden and delayed risks are highly embedded in models of economic developmentalism and brown economies. These models are deeply rooted in cognitive, institutional, and techno-institutional lock-ins. Furthermore, over the past two decades, brown economies with delayed hidden risks have been linked to deregulation, laissez-faire approaches, and market-oriented governance models in the past two decades (Chang 2012; Heo 2015; Kim 2007; Yao 2013).

2.3 Analytical framework

The literature summarizes the central thesis of developmental environmentalism as follows: First, even governments in this decade have to engage more in the environment, particularly climate governance, under global pressure, but they still prioritize industrial economic niches rather than focusing on decarbonization. Second, in some East Asian countries, governments’ mentality further entwined developmentalism with neoliberalism, by which policies and institutions ignored social and climate injustice. Third, to maintain neoliberal developmentalism, it is a recentralized bureaucracy rather than a formalistic democratic process that excludes civil society from core policymaking. Fourth, the carbon pricing policies met strong objections, even though the Japanese government launched a carbon tax in 2012, and South Korea began carbon trading in 2015.

This study explored how a recently recentralized bureaucracy, a carbon-intensive economy, and a high-carbon lock-in can meet international net-zero goals, mainly through carbon pricing. By identifying the systemic risks that Schweizer (2019) proposed, involving an examination of institutional and societal ignorance of climate and lags in policy and regulation implementation, this study aimed to analyze the effect of sluggish climate governance on carbon pricing in Taiwan. It is essential to respond to the reflective discussion of UNEP (2011) on whether the systemic risks of such a transition are critical factors behind governments’ failure of governments to adopt mainstream national climate policies UNEP (2011).

Taiwan has initiated a CCRA revision since 2020; this creates a fourth opportunity window for implementing carbon prices. Nevertheless, due to systemic transitional barriers, the government proposed a limited carbon fee instead of a comprehensive carbon tax. Therefore, using the analytical framework shown in Fig. 1, this study explains the transitional prediction of delayed climate governance on carbon pricing. The figure shows several structural conditions entangled by each other: First, the international advocacy of 2050 Net Zero Emission by COP26 and CBAM directly exerts pressure on a high carbon regime, which is locked in a brown economic body (UN 2021). Second, under the framework of developmental environmentalism, the government likely mastered climate policymaking by recentralized bureaucracy. Third, while the industry sector appreciated more communication with policymakers (with solid arrow lines), civil society was limited to communicating on carbon pricing policy (dashed line). Fourth, entangled climate policymaking eventually resulted in a hampered carbon fee rather than a comprehensive carbon tax. This study proposes an analytical framework to address sluggish climate governance.

3 Policy background and high carbon emission burden

3.1 Policy background

The Taiwanese government had three opportunities to implement an energy tax before explicitly proposing a carbon fee for the CCRA in 2021. Appendix see Table 5 indicates that in response to the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, the first National Energy Conference 1998 discussed energy taxation. In 2000, as part of Taiwan’s Agenda 21–Sustainable Development Strategy, the National Council for Sustainable Development proposed using energy policy tools and reviewing energy taxation measures. The Environmental Consensus Conference organized by the Executive Yuan in 2004 discussed changing the oil and gas excise duty to an energy tax or carbon tax. In 2006, when the Ministry of Finance and members of the Legislative Yuan proposed different versions of an energy tax bill, the Taiwan Economic Sustainable Development Conference held by the Executive Yuan actively discussed schedules and packages for implementing an energy tax.

In this context, during the 2008 election, the presidential candidates of the Democratic Progressive Party and Kuomintang (also known as the Chinese Nationalist Party, a significant party in Taiwan) expressed their support for introducing an energy tax. At the 3rd National Energy Conference in 2009, the Energy Tax Bill Act was listed together with the Energy Administration Act, Renewable Energy Development Act, and GRMA as the four GHG reduction acts in Taiwan (Liou 2011), which were discussed as green taxation by the Tax Reform Commission. With the 4th National Energy Conference in 2015 and the recently passed GRMA, the government planned to promote a tax system for imported fossil fuels; however, this system has not yet been implemented. All three opportunities were passed.

In 2017, the National Climate Change Action Guidelines promulgated by the Executive Yuan proposed implementing a GHG cap-and-trade scheme. Additionally, the Energy Transition White Paper, which involved the extensive participation of civil society and the Bureau of Energy in 2018, and the Taiwan Sustainable Development Goals promulgated by the Executive Yuan in 2019, indicated that Taiwan should implement related strategies and support plans in 2020 to levy energy and carbon taxes. Through these policies, a fourth opportunity for implementation is imminent. In May 2020, the EPA proposed the revision of the GRMA in response to the upcoming COP26 and CBAM. The government first clarified that it would impose a carbon fee. The name of the revised GRMA was officially changed to CCRA on December 30, 2020. Although the government has promised to implement a carbon pricing mechanism in 2022 formally, the government only discussed an administrative carbon fee rather than a complete carbon pricing mechanism. Currently, the EPA only plans to apply a carbon fee to manufacturers with high carbon emissions, and the control scale is limited, which differs from the carbon tax control approach of various regulatory departments.

3.2 High carbon emission structure

When the energy sector apportioned electricity consumption to various sectors, the GHG emissions in 2021 were dominated by the manufacturing sector (52.29%), followed by the residential (19.52%), transportation (11.94%), and energy sectors (12.62%) in Taiwan (EPA 2023a). Furthermore, in 2021, the top 30 and 10 GHG-emitting manufacturers accounted for approximately 79.32% and 68% of the total emissions of the manufacturing sector, respectively (Figs. 2 and 3 and Table 1). A mathematical conversion revealed that the top 10 manufacturers in terms of GHG emissions in 2021 accounted for approximately 35.95% of the country’s total GHG emissions. This shows a fatal flaw in Taiwan’s carbon emissions structure.

Source: Open Government Data Platform (EPA 2023a)

Proportion of GHG emissions by sector in 2021 in Taiwan

Among the top ten manufacturers by emissions in 2021, the Formosa Plastics Group in the petrochemical industry (including Formosa Petrochemical, Formosa Plastics, Formosa Chemicals and Fibre, and Nan Ya Plastics) accounted for approximately 31.24% of the GHG emissions of the entire manufacturing sector and 16.53% of the national GHG emissions. In addition, the chairperson of the group is currently the chairperson of the CNFI, which has considerable influence. The top three manufacturers in terms of GHG emissions, namely Formosa Petrochemical, China Steel, and Dragon Steel, accounted for approximately 32.12% of the emissions of the entire manufacturing sector and 19.9% of the national GHG emissions. Statistics on GHG emissions revealed clear control targets for Taiwan to reduce GHG emissions, achieve net-zero emissions, and implement a carbon pricing mechanism. For policymakers, Taiwan’s high carbon emissions structure is undoubtedly a systemic challenge in promoting carbon pricing.

4 Method

This study analyzes the perspectives of various stakeholders regarding the carbon fee policy in the CCRA and highlights the challenges Taiwan faces, which is lagging in its sustainable transition. The Appendix provides data on the focus groups and in-depth interviews.

4.1 Data collection

Interviews and data collection were conducted between May 2020 and April 2022. Five focus groups with 29 participants and semi-structured interviews with 23 respondents were conducted. Five focus group interviews involving critical stakeholders from governmental agencies (EPA, Bureau of Energy, Industrial Development Bureau, and National Development Council), high-carbon industries (petrochemistry industry, steel industry, and the Chinese Federation of Labor), scholars, parliament (members of the Legislative Yuan who have proposed bills from different parties), and NGOs were invited (Table 2). The participants of every focus group were mixed with different stakeholders, and the interview outline focused on carbon fee decision-making models. The effectiveness of a carbon fee in response to the CBAM, the sufficiency of a carbon fee as a climate policy, the opinions of industry personnel, and the adequacy of participation and communication were designed and sent to every participant in advance. Further, the study conducted semi-structured interviews with five types of key stakeholders involving governmental agencies, high-carbon industries, scholars, parliament members, and NGOs (see Table 3) according to the fundamental results of the focus groups. The analytical framework of the interviews was used to deepen and clarify relevant issues in carbon pricing policymaking, concerns by industries, critical viewpoints by experts, communicative transparency, and participation with NGOs. An outline was sent to each participant in advance. The topics were discussed in depth, recorded, and transcribed (see the summaries in Appendix see Table 6).

Additionally, the authors participated in 12 symposiums related to net-zero emissions and carbon taxes (including a poll analysis, a forum on risk society, seminars, energy reduction conferences, and the Academia Sinica Sustainability Platform Report on the Net Zero Consensus). The collected data included official documents from businesses and Taiwan’s Chinese National Federation of Industries (e.g., annual reports and company press releases) and gray literature (e.g., media articles, policy documents, research reports, and presentation materials) from third parties, such as think tanks, government agencies, universities, and NGOs).

4.2 Identification of climate governance delayism

The Taiwanese government has had three opportunities to impose an energy tax since 2006, but they have all failed (Chou and Liou 2023). The most recent CCRA revision proposed a carbon fee as a carbon pricing mechanism in response to pressure for further climate transition at home and abroad; this approach can be considered to represent governance delays in Taiwan. To analyze the government’s proposed carbon fee as an essential step in climate governance, this study focuses on large carbon emission manufacturers and policymakers’ efforts toward economic growth, participation, and communication. Based on these structural factors, this study further examines why the government is accelerating carbon fee proposals but has previously delayed and ignored carbon reduction policies.

This study analyzed the proportion of GHG emissions in 2021 of the top 30 and 10 large carbon emission manufacturers to highlight their influence. For policymaking toward economic growth, this study investigates the decision-making process of the government’s carbon fee, focusing on economic development and competitiveness. To participate and communicate, this study examined whether those involved in carbon-fee policymaking communicated entirely with civil society or solely with industry personnel through a recentralized bureaucracy.

5 Results

After five focus groups, 23 in-depth interviews, and detailed data collation (historical and policy context), the study had significant findings that reflected the given thesis of developmental environmentalism. The discussions in the focus groups and the in-depth interviews clearly distinguished the mentality, policies, institutions, and strategies of national development toward economic growth priority or sustainability, which were clearly distinguished and explored. Besides the interviewees from governmental agencies and industry, the interviewees from academia, NGOs, and congresses mostly positively responded to carbon pricing in the way of global green transition; they criticized the lag and limit policy of carbon fees and non-transparent policymaking. Even the industry had different views from the government and addressed competitive adaptation through the impact of carbon pricing. Overall, there are three crucial findings. First, Taiwan’s green transition is relatively slow, which can be attributed to the contradictions and conflicts within developmental environmentalism. This result has two significant consequences: Taiwan’s carbon pricing regulation lags behind Japan, South Korea, and many major countries worldwide, and the Taiwanese government can only set low carbon pricing with the most negligible impact on the industry. This finding is discussed in Sects. 5.1, 5.2, 5.3. Second, the study found that the government lacks a core green transition mentality and governance framework, manifested in the unclear government coordination and operational mechanisms of inter-ministerial committees. This is explained in Sect. 5.4. Third, the policymaking of carbon fees is still a bureaucratic redetermination by governmental elites with formalistic public participation. This is analyzed in Sect. 5.5.

5.1 Lag green transition under the developmental environmentalism

Various countries have focused on sustainable transition in response to the demand for a low-carbon society and implementing net-zero carbon emission policies (TWI 2050a, b 2019; EC 2019; IEA 2021a, b). Before COP26, the United Nations organized the 2050 net-zero coalition, and net-zero carbon emissions became a new focus in climate governance. Additionally, the EU announced that it would initiate the CBAM in 2023 (EC 2021), meaning that various countries reemphasized or formulated carbon tax policies or trading mechanisms.

As a nation with high carbon emissions, Taiwan faces pressure from the Net Zero Coalition and the CBAM to alleviate air pollution (WHO 2021) and obtain 100% of its energy from renewable sources. These sources of pressure could be key factors behind the sudden formulation of a carbon fee mechanism in Taiwan, which has lagged in climate governance. Taiwanese society opposed eight high-carbon-emission petrochemical construction projects that caused high PM2.5 levels in 2010 and expressed their opinion about removing coal from the energy mix in 2015. However, they cannot change decision-making and governmentalism in developing countries (Chou 2017; Walther 2018). Although the global demand for 100% renewable energy has attracted the industry’s attention, Taiwan’s internal energy transition is resisted by nuclear proponents rejecting the transition to renewable energy, and global demand is not the main factor driving related transitions (Chou 2018).

In October 2018, US President Donald Trump launched the China–USA trade war, which began to transform Taiwan’s global production chain and geopolitical relations, mainly through the inflow of substantial domestic and foreign capital, which reignited Taiwan’s economy (Xie 2019). However, in the face of enormous investment inflows, the Taiwanese government has not proposed a systematic review mechanism to strictly control carbon emissions and energy consumption of new investors in the manufacturing industry (RSPRC 2019). Additionally, carbon tax represents a low-carbon transition risk, and investors must assess this type of transition risk within firms to understand its impact on the investment decision-making process (Monasterolo et al. 2022). Manufacturing-oriented countries with high carbon emissions, such as South Korea, China, and Japan, announced their carbon neutrality plans in June and September 2020. However, Taiwan was slow to respond, and scientific assessments of basic carbon reduction policies and vision formulations have yet to begin (Chou 2020). Under pressure from external forces, the Executive Yuan did not officially set up the 2050 Net-Zero Carbon Emissions Task Force until April 8, 2021. In the same year, on April 22, President Tsai Ing-wen announced for the first time that net zero carbon emissions would be achieved, which is the goal that Taiwan would pursue (see Fig. 4).

Japan and South Korea, also affected by carbon lock-ins generated by the dominance of energy-intensive industries, began energy price-increase mechanisms after the 1973 oil crisis. Japan implemented a carbon tax in 2012 in response to global pressure to reduce carbon emissions, and South Korea implemented a carbon trading system in 2015. Taiwan’s electricity and water prices are much lower than the other two countries. Although Taiwan has had three opportunities to implement energy taxation since 2006, all have passed. Chou and Liou (2023) claimed that Taiwan is subject to a reinforced carbon lock-in, an unfavorable scenario for a sustainable transition.

When many countries announced their goal of carbon neutrality by 2050 or net-zero carbon emissions in 2020, Taiwan, accustomed to its brown economy system, did not respond immediately. The CBAM compelled the government to begin formulating carbon fees. Although the above sources of pressure created a transitional atmosphere, what forced this developmental country, with a reinforced carbon lock-in scenario, to take action was the CBAM’s carbon border tax, which directly affected Taiwan’s export competitiveness. In early 2020, the EPA revised the GRMA passed in 2015 and suggested imposing a carbon fee. Objections were made within industry circles, and the government’s lack of initiative did not change until July 2021, when the EU announced that it would be launched in 2023.

In the five focus group sessions and in-depth interviews, numerous government representatives, legislators, and scholars stated that Taiwan must implement carbon fees to boost its export competitiveness (Table 3). Any rationale that blocks the three previous opportunities for energy tax implementation—rising operating costs, reduced competitiveness, and increased unemployment—is no longer valid.

In the past, financial officials and the industry have voiced the strongest opposition. This time, however, it is direct global pressure on the economy and trade (Participant Number 24 in Focus Group 5thcalled F5#24; also, to all the other interviewee references in the brackets).

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Assessment Report and the United Nations Climate Change Conference exert slight pressure on governments. Taiwan is economically driven, and there must be a mechanism to activate the carbon border tax to apply direct economic pressure and force the government to change its decision (The 10th semi-structured interviewee called #10; also, to all the other interviewee references in the brackets).

The Taiwan government’s decision-making is almost constrained by pressure from industry leaders. The government had to respond because the CBAM would impose a carbon border tax; it would not react if it were not necessary (#7).

Therefore, Taiwan’s shift from a reinforced carbon lock-in scenario to one involving the traditional formulation of a carbon pricing mechanism was mainly due to pressure from the CBAM. However, it is still unclear whether the proposed carbon fee policy of the EPA can move Taiwan from a carbon lock-in path to a new low-carbon one.

5.2 Slow progress on carbon pricing but with a limited carbon fee

In August 2021, the CNFI voiced support for Taiwan’s establishing a carbon pricing mechanism in line with international carbon border tax policies for the first time in its 2021 White Paper of the CNFI (CNFI 2021). Nevertheless, the payers, price, use of carbon tax, and payers’ relationship with the carbon tax remain controversial. At the end of 2020, the EPA commissioned the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) to evaluate Taiwan’s carbon pricing mechanism (GRICCE 2020). Although the report suggested that Taiwan should implement carbon pricing as soon as possible under global pressure, based on Taiwan’s political and economic conditions, the government decided first to implement a carbon fee and then establish an emissions trading system subsequently.

Under the EPA plan, the carbon fee is equivalent to the air pollution fee and can only be levied by industrial firms. The carbon fee is an administrative control levy with limited scale and purpose. Thus, it differs from an energy/carbon tax, which should be the responsibility of the Ministry of Finance. According to Shaw et al. (2009), the carbon tax benefits income and wealth redistribution. The EPA began communicating with industry personnel about carbon fees in mid-2020. By the end of the year, it encountered specific difficulties in dealing with carbon-intensive industries, particularly the petrochemical industry (#1). Moreover, the chairman of the CNFI is also the chairman of the Formosa Plastics Group, which includes four of the top ten carbon-emitting manufacturers in the industrial sector and accounts for 20% of Taiwan’s total carbon emissions in 2020.

Although Article 5 of the revised bill of the CCRA (formerly the GRMA revision) announced by EPA in September 2021 still maintains the wording of “levying taxes on GHG consumption,” in Article 26, only a carbon fee is explicitly mentioned; this avoids the issue of an energy tax, which has been a controversial topic for more than a decade. For a long-term high-carbon lock-in economy, the imposition of green tax reforms is problematic in the context of cognitive, institutional, administrative, and market dimensions.

In a focus group session, a representative of the Taxation Administration of the Ministry of Finance emphasized that “there currently needed to be a timetable for implementing an energy tax. Energy tax must be executed when the economy is stable. Priority is given to implementing carbon trading or levies by the EPA” (F4#17). “Representatives of the Industrial Development Bureau and the Bureau of Energy will start collecting a carbon fee” (F4#18,19). Representatives of the CNFI and the Petrochemical Industry Association of Taiwan shared the same opinion and asserted that a more straightforward carbon fee should be imposed first. Moreover, fair collection principles, global competition, and international standards must be considered (F3#15). A representative of the Chinese Petroleum Corporation claimed that a carbon tax and levy should be implemented to avoid reducing its competitiveness(F4#21). A representative of the China Steel Corporation took air pollution control as an example and stated that the effect of tightening emission controls was more significant than air pollution fees and that a carbon fee was unnecessary (F4#20).

The Taiwan Climate Association, which consists of personnel from eight significant electronics manufacturers, including Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company and Delta Electronics, noted in a 2021 conference report that a carbon tax would negatively affect manufacturers within ten years (Chen 2021) and criticized the government for not being determined to implement carbon pricing, indicating that reforms were slow in response to an EU carbon border tax (F4#22). The Green Citizens’ Action Alliance, Citizens of the Earth, and Greenpeace emphasized that Taiwan should move from implementing carbon fees to imposing carbon taxes (F5#27, 28, 29). The Taiwan People’s Party legislators stated that the government has been slow to react to revising the legislation, so the carbon tax plan has been included in their party’s climate proposal (F3#13; #5). The former president of the Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research emphasized that carbon taxation is a green taxation system that involves carbon reduction, energy efficiency, and social equity and indicated that such a system is unavoidable (F5#24)—at a press conference for COP26, a spokesperson for the RSPRC (2021) suggested that the government should review the limited control of carbon fees and design an energy/carbon taxation policy. Chou et al. (2022) stated that the government should include sunrise provisions for carbon taxation in the CCRA in line with carbon fee implementation and accelerate its green transition in the era of net-zero carbon emission goals.

5.3 Low carbon fee and industry commitments

The LSE report commissioned by the EPA suggests that a carbon fee can start at US$10 and increase year by year. However, the outcomes of the intensive communication between the EPA and industrial groups were that the carbon fee would start from US$3 (NT$100) and would mainly be given back to the industry as a subsidy or special fund for energy efficiency improvement or carbon reduction equipment or technology. According to the CNFI (2021) questionnaire involving its members, 47% of manufacturers agreed that NT$100 is the most reasonable carbon fee (Zeng 2021). Additionally, the Deputy Minister of Economic Affairs stated that if the carbon fee were set at NT$300 per ton, the cost burden on the industry would be considerably high (Sun 2021). This development trend reveals that Taiwan’s carbon lock-in society is beginning to implement an industry-focused transition.

Although low-carbon pricing is welcomed by carbon-intensive industries (Huong et al. 2021), it divides them into other sectors, such as the electronics industry. For example, Delta Electronics’ internal carbon pricing was US$300 per ton (DELTA 2021). The Taiwan People’s Party representative stated that “if the carbon fee is only set at US$3 per ton, the international community will think that the government has no determination to implement a carbon fee and only wishes to deal with the concerns of the CBAM.” Therefore, the party’s legal draft set a starting price of US$10 per ton of carbon (#5). In addition, Greenpeace held a press conference on October 28, 2021, to announce the carbon pricing intentions of major carbon-emitting manufacturers in Taiwan. According to its survey, 69% of major carbon-emitting manufacturers claimed that a reasonable carbon fee would be NT$300 per ton, rejecting the suggestion that the EPA set a carbon fee of NT$100 per ton. The chairman of the Taiwan Institute for Sustainable Energy also agreed in a press conference that a meagre carbon fee would not align with international standards. Scholars have also stated that carbon pricing should not be excessively low. Some have indicated that to reflect global carbon pricing, the levy should be NT$300 per ton (F5#24, 25, 26; Chou et al. 2022).

Regarding carbon fees as a special fund for subsidizing carbon reductions in industries, the EPA has identified such levies as an incentive to achieve industrial carbon emission reductions (#1). However, different NGO representatives in the focus group emphasized that a carbon fee should be returned to disadvantaged groups (F5#28, 29). At the EPA law revision hearing at the end of 2021, the Green Citizens’ Action Alliance stated that using special funds would allow manufacturers to recoup taxes. The former president of the Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research noted that “the polluter pays a carbon fee, so it should no longer be used to subsidize these polluting manufacturers” (Sun 2021).

5.4 Lack of a core green transition mentality and governance framework

After several years of delay, Taiwan began to formulate a carbon pricing mechanism. It is not simply a carbon fee or carbon trading mechanism of the EPA; rather, it depends on several aspects, namely, whether the government proposes and establishes a comprehensive green transition mentality, whether an inter-ministerial operating mechanism is established, and whether a complete carbon pricing mechanism is established that transitions carbon fees to carbon taxes.

Although the Executive Yuan officially established a task force for net-zero carbon emissions, carbon pricing was not a core topic of discussion in 2021. In addition, after President Tsai declared 2050 net-zero carbon emissions as Taiwan’s sustainability-related goal on Earth Day, the government did not propose a comprehensive development plan and lacked a precise roadmap to achieve net-zero goals. Compared with the EU, South Korea, and the USA, which have proposed different green bills, the Taiwanese government lacks the above policy frameworks to instigate a core green transition (#8, 9, 10, 11).

Government representatives, legislators, and scholars have stated that Taiwan must impose carbon fees to boost its export competitiveness. Any rationale that blocked the three previous opportunities for energy tax implementation—rising operating costs, reduced competitiveness, and increased unemployment—is no longer valid. In other words, owing to a paradigm shift in the global low-carbon economy, the developmental value of green transition should be constructed without hesitation. Even in the face of CBAM, the government lacks the whole mindset to implement comprehensive carbon pricing, and the change is slow. Moreover, NGO representatives emphasized that carbon pricing should be given back to disadvantaged groups and urged a carbon tax instead of a limited carbon fee (#18, 19). They also rejected that using special funds would allow manufacturers to recoup their taxes; meanwhile, polluters pay a “carbon fee, so it should no longer be used to subsidize these polluting manufacturers” (Hsieh 2021). It meant that the mentality of developmental environmentalism had to be denied.

Furthermore, the coordination and operation mechanisms of inter-ministerial committees are underdeveloped; even if the levy of carbon fees follows the policy path of net-zero carbon emissions, various departments, including those covering energy, industry, construction, transportation, and housing, should implement carbon pricing to support Taiwan’s carbon reduction goals. Government agencies with primary responsibility appear to push the Energy Bureau and the EPA heavily; no inter-ministerial operation framework guides cooperation between relevant agencies such as the National Development Council, the Ministry of Finance, the Industrial Development Bureau, the Ministry of Transportation and Communications, the Construction and Planning Agency, and the Council of Agriculture (#8).

The EPA and the Ministry of Finance, which are directly responsible for carbon pricing, lack a dialogue framework. When civil society doubted the need to impose a carbon fee transitioning to a carbon tax, the EPA directly passed responsibility to the Ministry of Finance (Sun 2021). The director of the Climate Change Office responsible for the revision of the CCRA stated that the carbon tax levy was the responsibility of the Ministry of Finance and that the EPA could not intervene (#1). “Take air and water pollution fees as an example. The carbon fee imposed by the EPA cannot be high; once the tax rate is proposed, it will be discounted due to backlash from manufacturers, and the low carbon fee will not put pressure on the industry in promoting transition” (#8). Scholars have indicated the need for a precise inter-ministerial governance mechanism to bring clarity to carbon tax issues (F5#24, 25; Chou et al. 2022), and the media criticized the irresponsibility of the Ministry of Finance, stating that the CCRA revision was “a pseudo work” (Hsieh 2021).

Another vital reason for policy delay is the lack of an inter-ministerial operation framework (#8) due to the underdevelopment of clear green transition values, policies, and industrial strategies by the entire government and its agencies.

5.5 Bureaucratic re-centralization on the carbon fee policymaking

Over the past two decades, various major environmental movements have influenced Taiwan in the past 2 decades, and NGOs have been actively involved in confronting various societal issues (Ho 2018; Tu 2019). In such a democratic mechanism, when the government makes a significant decision, it is subject to verification and competition from civil society. However, decision-making with regime dominance has long caused distrust and conflict between the government and civil society (Chou 2017). Although the EPA has held several fora and public hearings and established an online participation platform (EPA 2021) focusing on CCRA revision and carbon fee issues, fundamental democratic participation and transparency are insufficient.

Although the EPA commissioned the LSE to conduct an evaluation study on carbon pricing in Taiwan and used this study as a professional basis for decision-making, there is no review mechanism for domestic experts, no process for extensive consultation with experts, and most scholars who care about climate issues are rarely considered and consulted (F5#24, 25, 26). In the revised CCRA, some of the opinions of NGO personnel were adopted (#7) or NGOs were invited to participate in panel discussions in a limited manner (F4#23). Essentially, the scope of NGO participation is limited. NGOs could only approximately guess the amount of a carbon fee (F5#27, 28, 29; #9) or hold a press conference to request that the EPA publicly explain the basis for setting the carbon fee to NT$300 per ton by LSE recommendations.

In other words, the government maintained a centralized, bureaucratic decision-making process regarding policy. Most importantly, although various public hearings have been held and an online participation platform has been established to include certain voices partially, the government holds its exclusive autonomy. From mid-2020 to 2021, the EPA held several communication sessions with industry personnel (#12); however, these sessions were not disclosed to the public, raising doubts about transparency. Civil society and scholars have criticized such communication for focusing only on the industry’s voice and lacking comprehensive inter-ministerial discussions (F5, #24, 25, 26; #5, 6, 8, 9).

Centralized policymaking by bureaucrats cannot respond directly to society’s demands, causing distrust among the government, industry, and society. To a certain degree, Taiwanese civil society already possesses socially robust knowledge sufficient to challenge and examine governmental policymaking procedures and assist with and expand the legitimacy of the decisions made (Chou 2017). Although a fourth opportunity was provided for carbon tax implementation, the policymaking process did not progress.

6 Discussion

Even after several East Asian countries announced the goal of carbon neutrality by 2050, Taiwan delayed its response; the real driving force behind implementing a carbon fee was the CBAM. Developmental countries locked into brown economies must change because they must be embedded in the global low-carbon market. However, the question must be: Can such a change help Taiwan break away from its original path and move toward a sustainable transition?

Taiwan’s carbon lock-in remains strong due to delayed legislation, limited carbon fees, low carbon pricing, special subsidies for industrial carbon reduction, and the lack of an appropriate mentality for establishing a comprehensive green transition framework. The government was conservative in launching a carbon fee mechanism with limited function and lacked extensive and transparent communication with society. It still adhered to the policymaking model of the developmental state, mainly focusing on communication with industry personnel. In particular, the government lacked a policymaking mechanism to form inter-ministerial committees (Table 3). Industry personnel do not favor this bureaucratic recentralized policymaking because, even after communication, the industry must still make appeals through various channels (CNA 2022).

Kim and Thurbon (2015) critically analyzed South Korea’s green growth policy. Although the South Korean government proposed a comprehensive and strategic green development strategy and introduced a carbon trading system under the development plan, the authors criticized it for supporting the competitiveness of the green technology industry, and environmental protection was considered complementary to economic goals. The authors claimed that the government typically follows the way of developmental environmentalism. Its economic priorities and industrial influences constrain South Korea’s green transition. The government is still transparent about the value of the green transition, policy framework, and industrial strategy. In 2020, President Moon Jae-in proposed the Green New Deal and attempted to lead South Korea toward net-zero emissions. In contrast, Taiwan is conservative and slow in formulating a carbon fee (see Table 4). The government has failed to propose clear green transition policies, values, or industrial strategies. Even if the carbon fee was associated with the national net-zero pathway, frameworks such as clear policy discussions and inter-ministerial policy coordination were unavailable. Even though Taiwan’s governance mechanism is developmental environmentalism, its delayed and unsystematic climate governance and transition confirmed the continued effect of the reinforced lock-in, as in Chou and Liou (2023), which hybridizes high-carbon structures, developmentalism, and governance delays.

Schweizer (2019) noted that if a country or society lags in regulation and perception, systemic risks are imposed, and the speed and outcome of societal transitions are hindered. Complex, nonlinear, and stochastic effects characterize societal transition. Any hidden risk gradually increases the risk to a tipping point, which leads to a domino effect and causes institutional breakdown. One interviewee was concerned about Taiwan’s carbon fee institution and worried that if related policymaking were delayed, unclear, or hasty, the nation’s climate transition would reach a critical point (#9). Furthermore, carbon fee or carbon tax constitutes a form of legal transition risk. Delays in a country’s carbon regulation can hinder societal responses to such transition risks, which are associated to the low-carbon transition risk as previously mentioned (Monasterolo et al. 2022). Instead, investors rely on the internal carbon pricing mechanism within firms to assess the legal transition risk of the firm and proactively respond to the requirements of the carbon management from political sectors or other agents.

7 Conclusion

In 2006, 2009, and 2015, Taiwan had three opportunity windows to open up energy tax. However, they all failed because the government was under pressure from industry (Chou and Liou 2023) and claimed that Taiwan is subject to a reinforced carbon lock-in, an unfavorable scenario for a sustainable transition, even if the fourth opportunity to implement carbon pricing is imminent. In May 2020, the EPA proposed revising the GRMA in response to the CBAM and clarified that it would impose carbon pricing for the first time. Nevertheless, until 2022, the government would only discuss limited administrative carbon fees rather than a complete carbon pricing mechanism.

The driving force that caused Taiwan to take action on carbon pricing was the “carbon border tax” of the CBAM, which directly affected Taiwan’s export competitiveness. Analyzing the carbon pricing policymaking, this study indicated that for a long time, objections were made within industry circles in the context of a brown economy. The government’s lack of initiative did not change until July 2021, when the EU announced it would launch in 2023. Nevertheless, the government has proposed a low price for a limited carbon fee and potential. Thus, a low carbon fee is insufficient to drive a low-carbon or sustainable transition. As previously mentioned (Nieddu et al. 2022), a primary reason for this is the carbon fee policy for sustainable transformation actors is not stringent enough.

This study shows that a country systemically embedded in a brown economy faces significant obstacles in constructing its climate governance. This heavily restricts policies, regulations, and institutions for national carbon reduction, particularly under a high-carbon manufacturing structure. As observed, even with exogenous solid pressure from the CBAM, Taiwan’s carbon pricing policy reform still lagged and shrunk. It reflected that the evolving policy formation of carbon pricing fits in the thesis of the given developmental environmentalism literature, not only the limited carbon fee institution but also the policymaking by the recentralized bureaucracy. Furthermore, it also showed the hybrid neoliberal developmental state, primarily inclined to prioritize industrial adaption for competition through slower, even more extensive regulation. The restricted carbon fee was temporarily regarded as a response to CBAM and global climate pressure without genuine concerns about decarbonization.

Consequently, the empirical findings highlight the application of the given thesis and explore novel theoretical visions of developmental environmentalism, particularly for high-carbon manufactured countries compelling green transition. First, brown economic agencies deeply embedded in the technical-institutional complex will powerfully shape the formation and creation of climate policy. Given the mentality of developmentalism, bureaucratic and industrial elites robustly resist green transition in different ways. Second, there is no doubt that the green economic paradigm shift has been ignored because of apparent industrial competition. Ignoring the risks of transition requires further delays in climate policy and formation.

Third, the hidden, delayed regulatory culture became the best partner of governmental bureaucratic elites, who likely recentralized policymaking without genuine democratic communication with civil society. Fourth, it generates systemic risks of green transition through institutional or societal ignorance. On the one hand, the lag climate policy seems hardly overturned due to undemocratic domination by the government and its fair policy discourse of industrial adaptation; on the other hand, the whole society will be diverted in those apparent policy reasonings and loss of awareness of an urgent global green transition. This causes fragments to boil frog in slowly heating water. An empirical study of carbon pricing in Taiwan provides evidence supporting these novel theoretical findings.

In summary, once the theory of developmental environmentalism meets the green transition, its nuclear thesis can be stretched to examine the lock-in effect of a high-carbon manufacturing path, even by a brown economy. Observing the laissez-faire doctrine of a hybrid neoliberal development state on how the government deregulates and re-regulates polluters or carbon emitters and further generates delayed, insufficient climate policies and carbon pricing without robust public scrutiny is significant. This implies a democratic deficiency through formalistic communication with civil society and the governance deficit of climate, which puts society into a transitional predicament. These synthesized theses demonstrate that the complex challenges of green transition can be applied to high-carbon societies, particularly emerging/manufactured industrial Asian Countries.

Data Availability

Data available on request.

Abbreviations

- CBAM:

-

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism

- CCRA:

-

The Climate Change Response Act

- EU:

-

European Union

- EPA:

-

Environmental Protection Administration of the Executive Yuan (Taiwan)

- GHG:

-

Greenhouse gas

- GRMA:

-

Greenhouse Gas Reduction and Management Act (Taiwan)

- MOEA:

-

Ministry of Economic Affairs (Taiwan)

References

Adom PK, Amuakwa MF, Agradi MP, Nsabimana A (2021) Energy poverty, development outcomes, and transition to green energy. Renew Energ 178:1337–1352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2021.06.120

As’jari F, Subandowo M, Bagus MD (2018) The application of green economy to enhance performance of creative industries through the implementation of blue ocean strategy: a case study on the creative industries. RJOAS 83(11):361–368. https://doi.org/10.18551/rjoas.2018-11.43

Barbier EB (2020) Greening the post-pandemic recovery in the G20. Environ Resour Econ 76(4):685–703. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-020-00437-w

Chang KS (1999) Compressed modernity and its discontents: South Korean society in transition. Econ Soc 28(1):30–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085149900000023

Chang KS (2010) The second modern condition? Compressed modernity as internalized reflexive cosmopolitization. Br J Sociol 61(3):444–464 (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20840427/)

Chang KS (2012) Predicaments of neoliberalism in the post-developmental liberal context. In: Chang KS, Ben F, Linda W (eds) Developmental politics in transition: the neoliberal era and beyond. Palgrave Macmillan, London, UK, pp 70–91

Chao J (2023). Carbon tariff: U.S. rules of the game. Infolink consulting. Available at https://www.infolink-group.com/energy-article/carbon-boarder-tax-how-the-us-plays-the-game. Accessed 24 May 2024

Chen E (2021) Peng CM: Taiwan climate partnership promoted supply chain management to net-zero. Smart City & IOT. Available at http://smartcity.org.tw/auto_detail.php?id=144&PHPSESSID=sbik4vugembf5almi19imbdsr0. Accessed 24 May 2024

Chou KT (2000) Bio-industry and social risk – delayed high-tech risk society. Taiwan: a Rad Quart Soc Stud 39:239–283 (https://www.airitilibrary.com/Publication/alDetailedMesh?docid=10219528-200009-x-39-239-283-a)

Chou KT (2002) The theoretical and practical gap of glocalization risk delayed high-tech risk society. Taiwan: A Radical Q in Soc Stud 45:69–122 (https://www.airitilibrary.com/Publication/alDetailedMesh?docid=10219528-200203-x-45-69-122-a)

Chou KT (2009) Issues of governance in scientific professionalism-SARS, H1N1, dioxin, BSE, melamine’s regulatory science and culture. Seminar on Medical Care and Society, Institute for Social Studies, Academia Sinica

Chou KT (2015) Predicament of sustainable development in Taiwan: inactive transformation of high-power consumption and high carbon emission industries and policies. Clean Energy 2:44–68 (https://scholars.lib.ntu.edu.tw/handle/123456789/392396)

Chou KT (2016) Beyond high carbon society. AIMS. Energy 4(2):313–30 (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297741138_Beyond_high_carbon_society)

Chou KT (2017) Sociology of climate change: high carbon society and its transformation challenge. National Taiwan University Press Taipei, Taiwan

Chou KT (2018) Tri-helix energy transition in Taiwan. In: Chou KT (ed) Energy Transition in East Asia. Routledge Press, London, UK, pp 45–73

Chou KT, Liou HM (2012) Analysis on energy intensive industries under Taiwan’s climate change policy. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev 16(5):2631–2642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2012.01.057

Chou KT, Liou HM (2020) Climate change governance in Taiwan: the transitional gridlock by a high-carbon regime. In: Koichi H, Dowan K, Shu K (eds) Chou KT. Climate Change Governance in Asia. Routledge Press, London, UK, pp 27–57

Chou KT, Liou HM (2023) Carbon tax in Taiwan: path dependence and the high carbon regime. Energies 16(1):513. https://doi.org/10.3390/en16010513

Chou KT, Shaw D, Hsu HH, Lin MX (2022) No time to wait: legislative climate act in Taiwan and carbon emission transformative strategy. Liberty Times. https://talk.ltn.com.tw/article/paper/1493483. Accessed 24 May 2024

Chou KT (2020) Taiwan declared the four fact of carbon neutrality. Economic Daily News. Available at https://rsprc.ntu.edu.tw/zh-tw/media-exposure/reports/1515-1209-tw-carbon-neutral.html. Accessed 24 May 2024

CNA (2022) Chinese National Federation of Industries’ seven recommendations call for 2050 net-zero emissions target not to be introduced into law in a hurry. Central News Agency (CNA). Available at https://ctee.com.tw/news/industry/575616.html. Accessed 24 May 2024

CNFI (2021) 2021 Annual chinese national federation of industries white paper. Chinese National Federation of Industries (CNFI). Available at https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rY83vR9K1C-o6EzAIvbp2QrYHf1W8-c3/view. Accessed 24 May 2024

DELTA (2021) Delta electronics joins RE100 – 100% renewable electricity and carbon neutrality targets for its global operations by 2030. Delta Electronics Inc. https://www.deltaww.com/en-us/news/14986. Accessed 24 May 2024

Dent CM (2012) Renewable energy in East Asia: towards a new developmentalism. Routledge Press, London, UK

Dent CM (2017) East Asia’s new developmentalism: state capacity, climate change and low-carbon development. Third World Q 39(6):1191–1210. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1388740

Droste N, Hansjürgens B, Kuikman P, Otter N, Antikainen R, Leskinen P, Pitkänen K, Saikku L, Loiseau E, Thomsen M (2016) Steering innovations towards a green economy: understanding government intervention. J Clean Prod 135:426–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.123

EASAC (2020) Towards a sustainable future: transformative change and post-COVID-19 priorities, A perspective by EASAC’s Environment Programme. European Academies Science Advisory Council (EASAC). https://easac.eu/publications/details/towards-a-sustainable-future-transformative-change-and-post-covid-19-priorities/. Accessed 29 October 2020

EC (2019) The European Green Deal. European Commission (EC). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:b828d165-1c22-11ea-8c1f-01aa75ed71a1.0002.02/DOC_1&format=PDF. Accessed 11 November 2019

EC (2021) Carbon border adjustment mechanism. European Commission (EC). Available at https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism_en. Accessed 24 May 2024

EEA (2002) Late lessons from early warnings: the precautionary principle 1896–2000. European Environmental Agency (EEA). https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/environmental_issue_report_2001_22 Accessed 09 January 2002

EPA (2020a) The mitigating of manufacturing industry CO2 emissions. Climate talks. Environmental protection administration (EPA). Available at https://www.climatetalks.tw/%E6%B0%A3%E5%80%99%E8%AE%8A%E9%81%B7%E5%9B%A0%E6%87%89%E6%B3%95. Accessed 24 May 2024

EPA (2020b) The GHG reduction action plan report in Taiwan. OECR, Environmental Protection Administration. https://www.ey.gov.tw/File/FA4B4A35EE23E674?A=C Accessed 19 November 2020

EPA (2021) Draft greenhouse gas reduction and management act amendment general info. Environmental protection administration. Available at https://enews.moenv.gov.tw/page/3b3c62c78849f32f/de5ace9a-814a-47cb-8273-342ec0664511. Accessed 24 May 2024

EPA (2023a) Annual GHG emissions. Opening government data. Environmental Protection Administration (EPA). Available at https://data.gov.tw/dataset/16059. Acessed 24 May 2024

EPA (2023b) The GHG inventory of carbon footprint registry. Environmental Protection Administration (EPA). Available at https://ghgregistry.moenv.gov.tw/epa_ghg/. Accessed 24 May 2024

Friedmann J, Fan J, Tang K (2018) Low-carbon heat solutions for heavy industry: sources, options, and costs today. Center on Global Energy Policy (CGEP). Available at https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/research/report/low-carbon-heat-solutions-heavy-industry-sources-options-and-costs-today. Accessed 24 May 2024

Funabashi H (2012) Why the Fukushima nuclear disaster is a man-made calamity. International. J Japanese Sociol 21:6576. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6781.2012.01161.x

GRICCE (2020) Carbon pricing options for Taiwan. Grantham Research Institute On Climate Change and the Environment (GRICCE). https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/publication/carbon-pricing-options-for-taiwan/. Accessed 24 May 2024

Han H (2015) Authoritarian environmentalism under democracy: Korea’s river restoration project. Env Polit 24(5):810–829. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2015.1051324

Heo I (2015) Neoliberal developmentalism in South Korea: evidence from the green growth policy-making process. Asia Pac Viewp 56(3):351–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12093

Ho MS (2018) The historical breakthroughs of Taiwan’s anti-nuclear movement: the making of a militant citizen movement. J Contemp Asia 48(3):445–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2017.1421251

Hsieh CF (2021) Why ministry of finance becoming an invisible man. The storm media. https://www.storm.mg/article/3946080. Accessed 24 May 2024

Huong K, Wu J, Cuei CT (2021) Carbon fee to be levied in 2023, first wave to target major carbon emitters. China times. Available at https://www.chinatimes.com/newspapers/20211014000450-260102?chdtv. Accessed 24 May 2024

IEA (2021a) World energy outlook 2021. International Energy Agency (IEA). Available at https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2021. Accessed 24 May 2024

IEA (2021b) Net Zero by 2050 A roadmap for global energy sector. International Energy Agency (IEA). https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/deebef5d-0c34-4539-9d0c-10b13d840027/NetZeroby2050-ARoadmapfortheGlobalEnergySector_CORR.pdf. Accessed May 2021

IMF (2023) Is the Paris agreement working? A stocktake of global climate mitigation. Available at https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/Staff-Climate-Notes/2023/English/CLNEA2023002.ashx. Accessed 24 May 2024

Jasanoff S (2005) Designs on nature science and democracy in Europe and the United States. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

Kameyama Y (2016) Climate change policy in Japan: From the 1980s to 2015. Routledge, London, UK

Kawakatsu T, Lee S, Rudolph S (2017) The Japanese carbon tax and the challenges to low-carbon policy cooperation in East Asia, Discussion papers e-17–009. Graduate School of Economics. Kyoto University. http://www.econ.kyoto-u.ac.jp/dp/papers/e-17-009.pdf . Accessed December 2017

Kim YT (2007) The transformation of the East Asian state: from the developmental state to the market-oriented state. Korean Soc Sci J 34:49–78

Kim ES (2015) The politics of climate change policy design in Korea. Env Polit 25(3):454–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2015.1104804

Kim SY, Thurbon E (2015) Developmental environmentalism: explaining South Korea’s ambitious pursuit of green growth. Polit Soc 43(2):213–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329215571287

Larissa B, Maran RM, Ioan B, Anca N, Mircea-Iosif R, Horia T, Gheorghe F, Speranta ME, Dan ML (2020) Adjusted net savings of CEE and Baltic nations in the context of sustainable economic growth: a panel data analysis. J Risk Financ Manag 13(10):234. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm13100234

Liou HM (2011) A comparison of the legislative framework and policies in Taiwan’s four GHG reduction acts. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev 15(4):1723–1747 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364032110004442)

Liu X, Ogisu K, Matsuo Y, Shishime T (2011) Opportunities and barriers of implementing carbon tax policy in Northeast Asia: a comparative analysis. Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES). Available at https://www.iges.or.jp/en/publication_documents/pub/discussionpaper/en/2174/full+paper_gcet11_liu.pdf . Accessed 24 May 2024.

Martinez CJ, Garza RA (2017) Establishing the framework: sustainable transition towards a low carbon economy. In: Baranova P, Conway E, Lynch N, Paterson F (eds) The Low carbon economy: understanding and supporting a sustainable transition. Palgrave MacMillan, London, UK, pp 15–31

Matsumoto M (2013) Structural disaster long before Fukushima: a hidden accident. Dev. Soc 42(2):165–190 (https://www.jstor.org/stable/deveandsoci.42.2.165)

MOEA (2022) Ministry of economic affairs manufacturing sector 2030 net zero transition pathway. https://www.go-moea.tw/carbonReduceZeroPath/manufacture. Accessed 24 May 2024

Monasterolo I, Dunz N, Mazzocchetti A et al (2022) Derisking the low-carbon transition: investors’ reaction to climate policies, decarbonization and distributive effects. Rev Evol Polit Econ 3:31–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43253-021-00062-3

Nieddu M, Bertani F, Ponta L (2022) The sustainability transition and the digital transformation: two challenges for agent-based macroeconomic models. Rev Evol Polit Econ 3:193–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43253-021-00060-5

Park DU, Kim J, Ou X, Wang C, Pham TN, Azuma M, Okayama J, Park C, Lee M, Song J (2022) Carbon neutrality in China, Japan and Korea. Science Portal Asia Pacific. https://spap.jst.go.jp/investigation/downloads/2022_c_01.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2024

RSPRC (2019) Taiwan in transformation: initiating a long-term energy transition. Risk Society and Policy Research Center (RSPRC), Taipei, Taiwan

RC (2021) [The Center’s Statement] The timing for climate change legislation is fleeting. Taiwan should fully respond to the net zero transition. Risk Society and Policy Research Center (RSPRC). Available at https://rsprc.ntu.edu.tw/zh-tw/m01-3/climate-change/1635-1115-tw-net-zero.html. Accessed 24 May 2024

Schweizer PJ (2019) Systemic risks – concepts and challenges for risk governance. J Risk Res 24(1):78–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2019.1687574

Shaw DY, Fu YH, Lin SM, Huang WH (2020) Carbon mitigation policy in Taiwan: subsidies or taxes? Green Economy 6:1–23 (https://lawdata.com.tw/tw/detail.aspx?no=393648)

Shaw DY, Huang YH, Chen MC, Chen PI, Hung CM, Yeh IH, Wang TI, Yang FC (2009) The analysis of green taxation, Chung-Hua Institution for Economic Research (CIER) http://www.cier.edu.tw/public/Attachment/910221126871.pdf. Accessed 24 May 2024

Shulla K, Voigt BF, Cibian S, Scandone G, Martinez E, Nelkovski F, Salehi P (2021) Effects of COVID-19 on the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Dis Sustain 2:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-021-00026-x

Sulich A, Zema T (2018) Green jobs, a new measure of public management and sustainable development. Eur J Environ Sci 8:69–75. https://doi.org/10.14712/23361964.2018.10

Sun WL (2021) How waiting much and use for the carbon fee? Environmental Information Center (EIC). Available at https://e-info.org.tw/node/233096. Accessed 24 May 2024

Tu WL (2019) Combating air pollution through data generation and reinterpretation: community air monitoring in Taiwan. EASTS 13:235–255. https://doi.org/10.1215/18752160-7267447

TWI 2050 (2018) Transformations to achieve the sustainable development goals. Report prepared by the world in 2050 initiative. International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA). http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/15347. Accessed 24 May 2024

TWI 2050 (2019) The digital revolution and sustainable development: opportunities and challenges. Report prepared by the world in 2050 initiative. International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA). https://pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/15913/. Accessed 24 May 2024

UN (2021) For a livable climate: net-zero commitments must be backed by credible action. United Nations (UN). Available at https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/net-zero-coalition. Accessed 24 May 2024

UNDP (2015) Mainstreaming climate change in national development processes and UN country programming: a guide to assist UN country teams in integrating climate change risks and opportunities. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). http://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/UNDP-Guide-Mainstreaming-Climate-Change.pdf Accessed 26 November 2015

UNEP (2011) Towards a green economy: pathways to sustainable development and poverty eradication - a synthesis for policy makers. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/126GER_synthesis_en.pdf Accessed 26 June 2011

UNFCC (2023) Report of the global environment facility to the conference of the parties. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cp2023_06_adv.pdf Accessed 22 September 2023

Walther D (2018) Insufficient trans-boundary risk knowledge and governance stalemate in Taiwan’s PM2.5 Policy-making. Dissertation, National Taiwan University

Xie JH (2019) The effects of reshoring are accelerating with Taishang. Wealth Magazine. Available at https://www.wealth.com.tw/articles/7acf9d05-ee69-4464-8808-96506f349f03

Yao SF (2013) Neoliberal globalization and Samsung’s new rise. National Taiwan University, Thesis

Zeng JY (2021) Chinese National Federation of Industries releases survey on carbon neutrality in the industrial sector is 70 % support a carbon fee and half think $100 per ton is the most reasonable. Apple Daily. Available at https://tw.appledaily.com/property/20211119/KVM46LLDKZH73POLYAGHMTZVYQ/