Abstract

This study investigates how brand experience, satisfaction, trust, and commitment influence brand loyalty. The results show that when these drivers separately affect brand loyalty, brand satisfaction and brand trust have a stronger effect on attitudinal loyalty than on behavioral loyalty, while brand experience and brand commitment have a stronger effect on behavioral loyalty than on attitudinal loyalty. When they are combined, however, their effects on brand loyalty are at least partially mediated. Moreover, brand satisfaction has the strongest effect on attitudinal loyalty, and brand commitment has the strongest effect on brand loyalty, whether they separately or jointly affect brand loyalty. Finally, research and managerial implications and limitations are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Brand loyalty is the core component of brand equity (Aaker, 1991). Scholars argue that building brand loyalty should be the top priority of marketing efforts and relationship marketing for many firms (Evanschitzky et al., 2012; Khamitov et al., 2019; Palmatier et al., 2006), because brand loyalty provides many benefits such as creating barriers to competitors, generating higher revenue streams, offering brand-extension opportunities, offering significant cost savings, and generating word of mouth (WOM) (Aaker, 1991; Keller, 2005). Ever since the brand loyalty concept was first introduced in the 1940’s (Schultz & Block, 2012), it has been studied extensively, especially during the last three decades, and numerous drivers of brand loyalty have been identified. Scholars have argued that brand experience, satisfaction (e.g., Kuikka & Laukkanen, 2012; Voss et al., 2010), trust (e.g., Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001; Garbarino & Johnson, 1999; Menidjel et al., 2017), and commitment (e.g., Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001; Dick & Basu, 1994; Garbarino & Johnson, 1999; Watson et al., 2015) are the most important drivers of brand loyalty.

However, brand loyalty results from a combination of many factors and cannot be explained by any single factor (Foroudi et al., 2018; Russo et al., 2016). Unfortunately, it is still not clear how these four major antecedents (brand experience, satisfaction, trust, and commitment) jointly affect brand loyalty. The ambiguous and sometimes conflicting findings regarding this question can be attributed to certain limitations in the literature. First, only a few studies have included all the above-mentioned antecedents, and most research has mentioned only a few of these drivers. Second, the studies have been carried out in different research contexts (Pan et al., 2012), such as in different countries or industries. Therefore, the findings are often conflicting and may not be generalizable across industries. Third, most studies have used a one-dimension scale to measure brand loyalty, although most scholars agree that loyalty is a two-dimension construct and using a one-dimension scale is highly problematic (Dick & Basu, 1994) Moreover, these studies have barely investigated whether the antecedents have different effects on attitudinal and behavioral loyalty. Fourth, some studies have investigated only the direct effects of antecedents on brand loyalty and have ignored the interrelationships of antecedents and possible mediation effects (e.g., Evanschitzky et al., 2012; Pan et al., 2012; Rather & Sharma, 2016; Rialti et al., 2017). However, the effects of certain variables on brand loyalty may change when other variables are included (Russo et al., 2016), or when their interrelationships and mediation effects are taken into account. Therefore, Russo et al. (2016) suggested that scholars should investigate the combined effects of predictors on brand loyalty, and Watson et al. (2015) suggested that scholars should examine how different antecedents affect brand loyalty differently.

Responding to their calls, this paper investigates how brand experience, satisfaction, trust, and commitment together affect brand loyalty. Specifically, this paper examines the interrelationship among these variables and whether their effects on brand loyalty are fully or partially mediated. Understanding the combined effects of antecedents on brand loyalty can help managers and practitioners to find a better strategy to build brand loyalty. Moreover, this paper will examine the combined effects of antecedents on brand loyalty across numerous industries using a two-dimension scale to measure brand loyalty.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. I first review the theoretical background on major determinants of brand loyalty. Second, I develop hypotheses based on the theoretical background and literature. Third, I describe the methodology and study design and report on tests of the hypotheses using AMOS 26 Graphics. Finally, I discuss the results, offer managerial implications, and discuss limitations and future research directions.

1 Theoretical background

1.1 Brand loyalty

Brand loyalty is defined as “a deeply held commitment to rebuy or re-patronize a preferred product/service consistently in the future, thereby causing repetitive same-brand or same brand-set purchasing, despite situational influences and marketing efforts having the potential to cause switching behavior” (Oliver, 1999, p. 34). Loyalty is positively related to higher performance outcomes such as higher sales and profits (Evanschitzky et al., 2012; Liu-Thompkins & Tam, 2013), positive word of mouth (Eelen et al., 2017; Muniz & O’Guinn, 2001), and brand equity (Aaker, 1991; Muniz et al., 2019). Initially (in the early literature in the 1950’s and 1960’s), brand loyalty was conceptualized and measured using repeat purchase behavior (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001; Day, 1969; McConnell, 1968; Tucker, 1964). Later, scholars argued that brand loyalty should be conceptualized as attitudes toward a brand (Day, 1969; Jacoby & Chestnut, 1978; Reichheld, 1996). Now, most scholars agree that brand loyalty is a two-dimensional construct that includes both attitudinal and behavioral loyalty (Baldinger & Rubinson, 1996; Chaudhuri, 1995; Fournier & Yao, 1997) because purchase behavior alone may correspond to spurious brand loyalty, but attitudinal loyalty alone may correspond to latent brand loyalty (Dick & Basu, 1994).

1.2 Brand experience

Providing brand experience is the first step in creating brand loyalty (Foroudi et al., 2018). Therefore, managing brand experience is one of the major concerns for any brand (Brakus et al., 2009; Iglesias et al., 2019; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016; Schmitt, 1999). Brand experience is defined as “subjective, internal consumer responses (sensations, feelings, and cognitions), as well as behavioral responses evoked by brand-related stimuli that are part of a brand’s design and identity, packaging, communications, and environments” (Brakus et al., 2009, p. 53). Brand experience consists of five dimensions: sensory, affective, behavioral, intellectual, and social experience (Brakus et al., 2009; Das et al., 2019; Schmitt, 1999). Brand experience is gained when consumers interact with brands directly or indirectly via numerous touch points through a variety of sources, channels, and media (Brakus et al., 2009; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). It can also be co-created with consumers (at the micro-level), communities, social groups, and sub-cultural groups (at the meso-level), or institutions, class systems, societies, and inter-societal systems (at the macro-level) (Andreini et al., 2018). Brand experience varies in valence, strength, and duration (Brakus et al., 2009). Consumers may have positive, neutral, or negative experience, and they may have stronger or more intense experience with a certain brand than others. After consumers have had multiple interactions or have accumulated experience with a brand, they will be more familiar and knowledgeable about it. Then they can determine whether they are satisfied with the quality of its product and trust its ability to deliver its promises (Anderson et al., 1994; Garbarino & Johnson, 1999), and they may become loyal to it (Ramaseshan & Stein, 2014).

1.3 Satisfaction

Brand satisfaction is the perceived difference between a consumer’s expectation and the actual performance of a product or service (Tse & Wilton, 1988), and it is a major driver of brand loyalty (Dick & Basu, 1994; Kuikka & Laukkanen, 2012; Voss et al., 2010). Consumers must have experience with a product or service to determine how satisfied they are with it (Anderson et al., 1994). There are two types of brand satisfaction: transaction-specific satisfaction and cumulative satisfaction (Boulding et al., 1993; Homburg et al., 2005). Transaction-specific satisfaction is based on a consumer’s evaluation of his or her experience with a particular product or service (Oliver, 1993; Olsen & Johnson, 2003). Cumulative satisfaction is a consumer’s overall evaluation of a product or service over time (Anderson et al., 1994; Johnson et al., 1995). Therefore, cumulative satisfaction has a stronger effect on behavioral and intentional outcomes (Anderson et al., 1997; Homburg et al., 2005; Olsen & Johnson, 2003). Moreover, brand satisfaction can also vary in strength (Chandrashekaran et al., 2007), and strongly-held brand satisfaction is a prerequisite for brand loyalty (Chandrashekaran et al., 2007; Reichheld, 2003). Many scholars have found that brand satisfaction has a positive impact on brand loyalty or on behavioral or intentional outcomes (e.g., Elsäßer & Wirtz, 2017; Trivedi & Yadav, 2020).

1.4 Trust

Trust is an essential part of any positive human interaction or exchange (Moorman et al., 1993; Morgan & Hunt, 1994). It is also the central construct in relationship marketing (Palmatier et al., 2006; Sirdeshmukh et al., 2002) and a major determinant of brand loyalty (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001; Garbarino & Johnson, 1999; Menidjel et al., 2017). Pan et al. (2012) argue that brand trust is the most important driver of brand loyalty because it explains about 33% of variance of brand loyalty. Brand trust is defined as “the willingness of the average consumer to rely on the ability of the brand to perform its stated function” (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001, p. 82). Brand trust, which is based on direct or indirect experience and cumulative satisfaction (Ganesan, 1994; Keller, 1993), is composed of a cognitive dimension and an affective and emotional dimension (Delgado-Ballester et al., 2003). First, brand trust involves confidence in the quality and reliability of the products and services offered. Second, it involves confidence in the honesty and integrity of the company and its employees (Delgado-Ballester et al., 2003; Garbarino & Johnson, 1999; Sirdeshmukh et al., 2002). Specifically, the company and its associates are believed to act in the consumers’ best interest and to not take opportunistic advantage of consumers’ vulnerability (Delgado-Ballester & Munuera-Alemán, 2001; Michell et al., 1998). Trust reduces the perceived risk and information costs associated with purchasing a product or brand (Delgado-Ballester & Munuera-Alemán, 2001; Ganesan, 1994; Paulssen et al., 2014).

1.5 Commitment

Brand commitment is defined as consumers’ emotional attachment to a brand, which drives their desire to maintain their relationship with it and patronize it over time, as well as counteracting efforts to make them change their preference (Germann et al., 2014; Hsiao et al., 2015). Therefore, brand commitment has two dimensions: affective and continuance commitment (Fullerton, 2003; Gruen et al., 2000; Gustafsson et al., 2005). Consumers are reluctant to commit to a company or brand if they do not trust it (Aurier & N’Goala, 2010).

Emotional attachment is driven by two major factors. First, it depends on the degree to which a brand’s personality matches the consumers’ self-concept (Albert et al., 2008; Huang, 2017; Kleine et al., 1993; Park et al., 2010) because people have a strong desire to incorporate others (e.g., other people or brands and products) into their self-concept (Park et al., 2010). The more a brand is consistent with the self-concept of its consumers, the more strongly the consumers will be attached to the brand (Malär et al., 2011; Matzler et al., 2011). Second, consumers can build an emotional bond with a brand if it can become a physical and emotional haven for them, offering support and comfort (Bowlby, 1969). Specifically, a product should be available when desired, perform its basic functions, and deliver expected value to its consumers (Paulssen, 2009; Pedeliento et al., 2016). Attachment varies in strength, and higher levels of attachment involve feelings such as affection, connection, passion, and even love (Albert et al., 2008; Aron & Westbay, 1996; Thomson et al., 2005). A strong attachment is developed over time through interactions between consumers and a brand (Baldwin et al., 1996).

Consumers not only want to build an emotional bond with a brand but also believe that “an ongoing relationship with another is so important as to warrant maximum efforts at maintaining it” (Morgan & Hunt, 1994, p. 23). They actively invest their financial, time, and social resources to maintain the brand relationship because they do not want to be merely recipients of the resources of a brand (Park et al., 2010). Consumers are highly committed to a brand because they do not want to lose something they trust and value (Fullerton, 2003), and they try to avoid the high risks and uncertainties they may associate with purchasing other brands (Belaid & Behi, 2011). Consumers who are committed to a brand are “less likely to patronize other firms and to become ‘always a share’ client” (Aurier & N’Goala, 2010, p. 308) and are less likely to accept competitors’ offers and maintain multiple business relationships (Ahluwalia et al., 2000, 2001; Swaminathan et al., 2007).

2 Hypothesis development

2.1 Direct effect

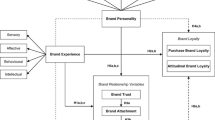

The proposed model is shown in Fig. 1. Building a brand experience is the first step in creating brand loyalty (Foroudi et al., 2018). After consumers have gained experience with a brand, they will be more familiar with and knowledgeable about it, then they can determine whether they are satisfied with and trust that brand (Anderson et al., 1994; Garbarino & Johnson, 1999), and they may become loyal to it (Ramaseshan & Stein, 2014), as consumers tend to repeat satisfied and pleasurable purchasing experiences (Brakus et al., 2009). Scholars have demonstrated that brand experience is positively related to brand satisfaction (e.g., Brakus et al., 2009; Iglesias et al., 2019; Pansari & Kumar, 2017). Moreover, scholars have also found that it is also significantly related to brand loyalty (e.g., Brakus et al., 2009; Ramaseshan & Stein, 2014; Sahin et al., 2011; van der Westhuizen, 2018).

However, brand experience may have different effects on attitudinal loyalty and behavioral loyalty. Since brand experience is the first step in building brand loyalty, it may have stronger effects at early phases, such as the cognitive and affective phases of brand loyalty, than in later phases, such as the conative and action phases. Moreover, Brakus et al. (2009) and Liu-Thompkins and Tam (2013) also argue that attitudinal loyalty is driven mainly by evaluations of previous shopping experience with a brand. Therefore, I hypothesize the following:

H1: Brand experience will have a stronger effect on attitudinal loyalty than on behavioral loyalty.

Consumers are satisfied when the performance of the products or services of a brand meets their expectations (Tse & Wilton, 1988), and they may not trust a brand until they are satisfied with it (Ganesan, 1994; Keller, 1993; Ravald & Grönroos, 1996). As a result, satisfied consumers may want to continue or maintain their behavior, vis-a-vis a brand in the future and are less interested in alternative brands (Menidjel et al., 2017).

Numerous studies have found that there is a strong and positive relationship between brand satisfaction and brand trust (e.g., Atulkar, 2020; Giovanis, 2016; Horppu et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2015; Paulssen et al., 2014). Moreover, scholars also have found that brand satisfaction affects brand loyalty intentions or behaviors directly (e.g., Brakus et al., 2009; Chandrashekaran et al., 2007; Elsäßer & Wirtz, 2017; Sahin et al., 2011; Szymanski & Henard, 2001; Trivedi & Yadav, 2020). However, brand satisfaction may have different effects on attitudinal loyalty and behavioral loyalty. Since attitudinal loyalty is driven mainly by evaluations of previous shopping experiences with a brand (Brakus et al., 2009; Liu-Thompkins & Tam, 2013), and brand satisfaction is based on positive shopping experience, satisfaction may have a stronger effect on attitudinal loyalty than on behavioral loyalty. Therefore, I expect that:

H2: Brand satisfaction will have a stronger effect on attitudinal loyalty than on behavioral loyalty.

Brand trust is defined as “the willingness of the average consumer to rely on the ability of the brand to perform its stated function” (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001, p. 82). As the central construct of relationship-marketing, brand trust is the key driver of not only brand commitment (Morgan & Hunt, 1994; Palmatier et al., 2006; Sirdeshmukh et al., 2002), but also brand loyalty (Chaudhuri & Holbrook, 2001; Garbarino & Johnson, 1999). Brand commitment is based on the consumer’s satisfied interaction and experience with a brand that develops over time (Baldwin et al., 1996) Consumers are reluctant to commit to a company or brand if they do not trust it (Aurier & N’Goala, 2010; Morgan & Hunt, 1994). Numerous studies have found that brand trust has a positive impact on brand commitment (e.g., Aurier & N’Goala, 2010; Delgado-Ballester & Luis Munuera-Alemán, 2001; Giovanis, 2016; Morgan & Hunt, 1994; Nadeem et al., 2020). Moreover, many scholars have also demonstrated that brand trust is positively related to loyalty intentions or behaviors (e.g., Aurier & N’Goala, 2010; Belaid & Behi, 2011; Menidjel et al., 2017; Nguyen et al., 2018; Sirdeshmukh et al., 2002; Trivedi & Yadav, 2020). Since brand trust is based on direct or indirect experience and cumulative satisfaction (Ganesan, 1994; Keller, 1993), it may have a stronger effect on attitudinal loyalty than on behavioral loyalty. Therefore, I hypothesize that:

H3: Trust will have a stronger effect on attitudinal loyalty than on behavioral loyalty.

Consumers not only want to build an emotional bond with a brand but also maintain an ongoing relationship with it (Morgan & Hunt, 1994). Consumers who are committed to a brand are “less likely to patronize other firms and to become ‘always a share’ client” (Aurier & N’Goala, 2010, p. 308) because they do not want to lose something they trust and value (Fullerton, 2003), and they try to avoid the high risks and uncertainties associated with purchasing other brands (Belaid & Behi, 2011). Moreover, they are less likely to accept competitors’ offers and maintain multiple business relationships (Ahluwalia et al., 2000, 2001; Swaminathan et al., 2007).

Many scholars have demonstrated that brand commitment is positively related to loyalty intentions and behaviors (e.g., Li et al., 2020; Nyadzayo et al., 2018; Park et al., 2010; Thomson et al., 2005). Consumers who have built a strong emotional attachment with a brand are more likely to incorporate it into their self-concept (Malär et al., 2011; Matzler et al., 2011; Park et al., 2010). They are motivated to express their self-concept through the purchase and consumption of a brand (Sirgy, 1982). Moreover, consumers also believe that “an ongoing relationship with another is so important as to warrant maximum efforts at maintaining it” (Morgan & Hunt, 1994, p. 23) and do not want to lose something they trust and value (Fullerton, 2003). They actively invest their financial, time, and social resources to maintain the brand relationship because they do not want to be merely recipients of a brand’s resources (Park et al., 2010). Therefore, although brand commitment can also drive attitudinal loyalty, it may have a stronger effect on behavioral loyalty. Therefore, I expect the following:

H4: Commitment will have a stronger effect on behavioral loyalty than on attitudinal loyalty.

According to previous discussions, brand experience is positively related to brand satisfaction; brand satisfaction can affect brand trust, which drives brand commitment. Therefore, I expect that:

H5: There will be a chain effect from brand experience to brand satisfaction to brand trust to brand commitment.

2.2 Mediation effect

Although the effects of brand experience, satisfaction, trust, and commitment on brand loyalty have been widely studied, how they jointly affect brand loyalty is still ambiguous, and sometimes the findings are conflicting. For example, it is unknown whether the effect of experience is fully or partially mediated by brand satisfaction, trust, and commitment, whether the effect of brand satisfaction is fully or partially mediated by brand trust and commitment, and whether the effect of brand trust is fully or partially mediated by brand commitment.

These unclear and inconsistent findings can be attributed to a few factors. First, only a few studies have investigated the joint effects of these antecedents on brand loyalty, and most research has included only a few of these drivers. Second, these studies were carried out in different research contexts (Pan et al., 2012). They were based on different industries (e.g., banking, retailing, wireless services, restaurants, mobile phones, cars, sportswear, disposable nappies, etc.) and in different countries (e.g., France, Spain, Saudi Arab, Korea, India, etc. See Table 1 for summary). Third, these studies used different measurements of brand loyalty (Pan et al., 2012). While some studies used a two-dimension or four-dimension scale, most were based on a one-dimension scale (about 70%; see Table 1). Fourth, some studies have investigated only the direct effects of antecedents on brand loyalty while ignoring their interrelationships and possible mediation effects (e.g., Evanschitzky et al., 2012; Li et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2012; Rather & Sharma, 2016; Rialti et al., 2017; Trivedi & Yadav, 2020). However, the effects of variables on brand loyalty may be expected to change when other variables are included (Russo et al., 2016) or when their interrelationships and mediation effects are considered. Even the studies that have investigated the possible mediation effects have also found mixed results. Some scholars have found that the effect of brand experience on brand loyalty is fully mediated by affective commitment (e.g., Iglesias et al., 2011) or by both brand trust and commitment (Khan et al., 2020), while others have found that the effect of brand experience was partially mediated by brand satisfaction (e.g., Brakus et al., 2009; Sahin et al., 2011), brand trust (Sahin et al., 2011), or both brand attachment and commitment (e.g., Ramaseshan & Stein, 2014). In a study of the mediation effects of brand love and brand trust on the relationship between brand experience and attitudinal and behavioral loyalty, Huang (2017) found mixed results.

Scholars have found that the effects of brand satisfaction on brand-loyalty intentions or behaviors are fully mediated by brand trust (e.g., He et al., 2012) or brand commitment (e.g., Aurier & N’Goala, 2010; Davis-Sramek et al., 2009), while others have found that the effects of brand satisfaction are partially mediated by brand trust (e.g., Atulkar, 2020; Aurier & N’Goala, 2010; Javed & Wu, 2020; Lee et al., 2015; Menidjel et al., 2017; Paulssen et al., 2014), brand commitment (e.g., Han et al., 2018), or both brand trust and brand commitment (e.g., Bove & Mitzifiris, 2007; Miquel-Romero et al., 2014).

Other scholars have found that the effects of brand-trust on brand-loyalty intentions or behaviors are partially mediated by brand satisfaction (e.g., Chiou & Droge, 2006; Harris & Goode, 2004; Jin et al., 2016; Park et al., 2017) or brand commitment (e.g., Aurier & N’Goala, 2010; Bove & Mitzifiris, 2007), while others have found that the effects of brand trust on brand loyalty are fully mediated by brand commitment (e.g., Miquel-Romero et al., 2014; Nadeem et al., 2020). Since the empirical studies for these mediation effects have conflicting results, I expect:

H6: The effect of brand experience on (a) attitudinal loyalty and (b) behavioral loyalty will be at least partially mediated.

H7: The effect of brand satisfaction on (a) attitudinal loyalty and (b) behavioral loyalty will be at least partially mediated.

H8: The effect of brand trust on (a) attitudinal loyalty and (b) behavioral loyalty will be at least partially mediated.

3 Methodology

3.1 Sample and data collection

This study employed an online survey, which was hosted on Google Forms and posted on Amazon MTurk to recruit participants, who were told they had to be loyal to a brand to be eligible for the study. After they agreed to participate in the study, they were asked to recall a brand to which they were loyal. A similar method has been used by many scholars (e.g., Das et al., 2019; Karjaluoto et al., 2016; Thomson et al., 2005). In all, 501 participants took the survey. Please see the participants’ profile and demographic information in Table 2. The most represented brands were Apple (12.2%), Nike (11.2%), Samsung (8.8%), Sony (2.6%), Adidas (2.2%%), and Coca Cola (1.2%), with 13.6% of the participants had used the brand for less than three years, 34.9% had used the brand between three and five years, 19% had used the brand between six and ten years, and 32.5% had used the brand for more than ten years. Females and males represented 49.1% and 50.9% of the participants, respectively (see participants’ demographics in Table 2). In all, 1.3% of the participants were between 18 and 20 years old, 36.4% were between 21 and 30 years old, 38.7% were between 31 and 40 years old, 11.8% were between 41 and 50 years old, 9.6% were between 51 and 60 years old, and 2.3% were over 60 years old. Income demographics include: 17.1% of the participants made less than $25,000 annually, 38.4% made between $25,000 and $49,999, 25.1% made between $50,000 and $74,999, 13.3% made between $75,000 and $99,999, and 2.3% made more than $100,000. The data shows that the sample was highly diversified and represented the population well.

3.2 The construct measurement

Brand experience included five dimensions: sensory, affective, behavior, intellectual, and social experience dimensions. Every sub-experience measure contained three questions adapted from those used by Brakus et al. (2009) and Schmitt (1999). The brand satisfaction measure included eight items adapted from those used by Dodds et al. (1991), and Kuikka and Laukkanen (2012). The brand trust index included five items adapted from those used by Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001) and Delgado-Ballester et al. (2003). The brand commitment index consisted of two parts: emotional attachment and continuance commitment. The measurement of emotional attachment included seven items adapted from those used by Garbarino and Johnson (1999), Matzler et al. (2011), and Swaminathan et al. (2008). Similarly, the continuance commitment index included three questions adapted from those used by De Wulf et al. (2001) and Palmatier et al. (2009). The attitudinal loyalty index included eight items adapted from those used by Chaudhuri and Holbrook (2001), Picón et al. (2014), and Watson et al. (2015). Finally, the behavioral loyalty index included seven items adapted from those used by Algesheimer et al. (2005) and Watson et al. (2015). All items were based on a seven-point Likert scale anchored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

3.3 Reliabilities and validities of measurement scales

An exploratory factor analysis with principal factor analysis and Promax rotation was first conducted on SPSS. For brand experience, all three sensory-experience items were loaded on one factor, and two behavioral-experience items and three intellectual-experience items were loaded on another factor. Four items from brand satisfaction were retained for the brand satisfaction index, while five items from brand trust were loaded on the brand trust scale. All seven emotional attachment items and two continuance commitment items were loaded on one factor. Five items of attitudinal loyalty and three items of behavioral loyalty were loaded on the attitudinal loyalty scale. Four items for behavioral loyalty were kept. All factor loadings were greater than 0.5, and no cross-loading factor difference was smaller than 0.2.

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed on AMOS 26. One item from each of the brand experience, brand trust, attitudinal loyalty, and behavioral loyalty scales was dropped. Another CFA was performed. The model fit was good (χ2(482) = 1042.972, p < 0.01; χ2/df = 2.164; GFI = 0.894, AGFI = 0.869, NFI = 0.911, TLI = 0.941, CFI = 0.950, RMSEA = 0.048). All factor loadings were significant (p < 0.01), supporting convergent validity. The factor loadings ranged from 0.713 to 0.888 for experience, from 0.754 to 0.802 for brand satisfaction, from 0.699 to 0.806 for brand trust, from 0.706 to 0.850 for brand commitment, from 0.710 to 0.795 attitudinal loyalty, and from 0.637 to 0.848 for behavioral loyalty. Moreover, the AVE and Composite Reliability (C.R.) of all measures exceeded the recommended minimums of 0.5 and 0.7, respectively (Bagozzi & Yi, 1998; Fornell & Lacker, 1981). Cronbach’s alpha exceeded 0.7 for all measures. Moreover, discriminant validity was supported because the estimated pairwise correlations between factors did not exceed 0.85 and were significantly less than one (Bagozzi & Yi, 1998), and the square root of the AVE for each construct was higher than the correlations between them (except for the correlation between brand satisfaction and attitudinal loyalty) (Fornell & Larcker, 1981) (see Tables 3 and 4). A common latent factor with a marker variable was performed using SPSS AMOS, and common variance was about 46.2%. Therefore, Common Method Bias was not a major issue in this study.

3.4 Results

I first investigated the effects of these four antecedents on brand loyalty separately. AMOS was used to check the effect of brand experience, satisfaction, trust, and commitment on attitudinal loyalty and behavioral loyalty (see Table 5). The model fit of four models was good (χ2/df < 3.00; GFI, AGFI, NFI, TLI & CFI > 0.9; RMSEA < 0.06). Brand experience has a stronger effect on behavioral loyalty than on attitudinal loyalty (βattitudinal loyalty = 0.497, p < 0.01; βbehavioral loyalty = 0.713, p < 0.01). H1 was reversed. Brand satisfaction has a stronger effect on attitudinal loyalty than on behavioral loyalty (βattitudinal loyalty = 0.883, p < 0.01; βbehavioral loyalty = 0.373, p < 0.01). H2 was supported. Brand trust has a stronger effect on attitudinal loyalty than on behavioral loyalty (βattitudinal loyalty = 0.356, p < 0.01; βbehavioral loyalty = 0.532, p < 0.01). H3 was supported. Brand commitment has a stronger effect on behavioral loyalty than on attitudinal loyalty (βattitudinal loyalty = 0.497, p < 0.01; βbehavioral loyalty = 0.713, p < 0.01). H4 was supported. Next, I investigated how these antecedents together affected brand loyalty. The model fit was good (χ2(485) = 950.344, p < 0.01; χ2/df = 1.959; GFI = 0.902, AGFI = 0.879, NFI = 0.919, TLI = 0.952, CFI = 0.958, RMSEA = 0.0044; see Table 6 and Fig. 2).

As expected, brand experience had a significant effect on brand satisfaction (β = 0.392, p < 0.01), brand satisfaction had a significant effect on brand trust (β = 0.886, p < 0.01), and brand trust was positively related to brand commitment (β = 0.258, p < 0.01). Moreover, attitudinal loyalty is positively related to behavioral loyalty (β = 0.495, p < 0.01). Therefore, hypotheses 5 was supported. Brand experience had a significant, direct effect on behavioral loyalty (β = 0.143, p < 0.01), but its direct effect on attitudinal loyalty was insignificant (β = -0.032, p > 0.1). The bootstrapping method showed that the indirect effects from brand experience to attitudinal loyalty [95% CI (0.075, 0.354), p < 0.01] and behavioral loyalty [CI (0.028, 0.177), p < 0.01] were significant. Therefore, the effect of brand experience on attitudinal loyalty was fully mediated but its effect on behavioral loyalty was partially mediated. H6 was supported.

Brand satisfaction had a significant, direct effect on both attitudinal loyalty (β = 0.27, p < 0.01) and behavioral loyalty (β = 0.444, p < 0.5). The bootstrapping method showed that the indirect effect from brand satisfaction to attitudinal loyalty is not significant [CI (−0.155, 0.208), p > 0.1], but the indirect effect from brand satisfaction to behavioral loyalty is significant [CI (0.319, 1.422), p < 0.01]. Therefore, the effect of brand satisfaction on attitudinal loyalty was not mediated. Brand satisfaction still had a strong, direct effect on attitudinal loyalty. However, the effect of brand satisfaction on behavioral loyalty was partially mediated. H7b was supported, but H7a was not supported. The direct effects of brand trust on both attitudinal loyalty (β = 0.065, p > 0.1) and behavioral loyalty (β = 0.174, p > 0.1) were insignificant. Moreover, brand commitment was positively related to behavioral loyalty (β = 0.392, p < 0.01), but its effect on attitudinal loyalty was not significant (β = 0.002, p > 0.1). Moreover, the indirect effect from brand trust to attitudinal loyalty is not significant [CI (-0.014, 0.014), p > 0.1], but the indirect effect from brand trust to behavioral loyalty (BL) is marginally significant [CI (−0.049, 0.3738), p < 0.01]. Therefore, the effect of brand trust on attitudinal loyalty is not mediated by brand commitment, but the effect of brand trust on behavioral loyalty was fully mediated. H8b was supported but H8a was not supported.

4 General discussion

4.1 Research implications

Loyalty has been studied for many decades, and many antecedents of brand loyalty have been identified. Scholars have argued that brand experience, satisfaction, trust, and commitment are the most important drivers of brand loyalty. However, scholars have rarely investigated how these four antecedents affect brand loyalty jointly, even though it is understood that brand loyalty is not the result of any single factor but comes from the combined effect of many factors (Foroudi et al., 2018; Russo et al., 2016). Moreover, findings on how these antecedents jointly affect brand loyalty are still ambiguous and sometimes conflicting. Therefore, the current paper investigates how brand experience, satisfaction, trust, and commitment jointly influence both attitudinal loyalty and behavioral loyalty. The results show that when these drivers separately affect attitudinal loyalty and behavioral loyalty, brand satisfaction and trust have stronger effects on attitudinal loyalty than on behavioral loyalty, but brand experience and commitment have a stronger effect on behavioral loyalty than on attitudinal loyalty.

In contrast to my hypothesis, my findings show that brand experience has stronger effect on behavioral loyalty than on attitudinal loyalty. This finding is not very surprising because purchasing behavior is largely based on the consumption experience of consumers, who are more likely to repeat a satisfied experience and less likely to repeat an unsatisfied experience. When these antecedents are combined, however, the drivers have different effects on attitudinal loyalty and behavioral loyalty. The effects of brand experience on attitudinal loyalty and the effects of brand trust on behavioral loyalty are fully mediated. The effects of brand experience on behavioral loyalty and the effects of brand satisfaction on behavioral loyalty are only partially mediated. The effects of brand satisfaction and trust on attitudinal loyalty are not mediated. Moreover, brand satisfaction has the strongest positive effect on attitudinal loyalty but has the strongest negative effect on behavioral loyalty, and brand commitment has the strongest positive effect on behavioral loyalty.

This study sheds light on brand loyalty literature by investigating the joint effects of brand experience, satisfaction, trust, and commitment on attitudinal loyalty and behavioral loyalty. This study also shows that brand experience, satisfaction, trust, and commitment have different effects on attitudinal and behavioral loyalty when they affect brand loyalty jointly versus when they affect brand loyalty separately. Moreover, this study contributes to the literature by covering a wide range of industries, such as consumer electronics, apparel and accessories, beverages and drinks, autos, cosmetics, musical instruments, home appliances, foods, and tools, as well as looking at 200 brands, while most studies researching the effects of these antecedents have been based on only one or two industries or even a few brands. Therefore, the findings in the current study are more generalizable than those of previous works. Finally, this study reconciles the ambiguous findings in the literature by adapting the two-dimension measurement of brand loyalty developed by Watson et al. (2015), while most studies have used only a one-dimension scale, which is highly problematic.

Russo et al. (2016) found that the effects of variables on brand loyalty may change when other variables are included. Moreover, the effects of variables on brand loyalty may also change when their interrelationships and mediation effects are considered. Findings from my study confirm these arguments. Although brand experience, satisfaction, trust, and commitment can affect loyalty separately, their effects on brand loyalty change when the chain effect from brand experience to brand satisfaction to brand trust to brand commitment is considered. Therefore, scholars investigating the effects of variables on brand loyalty should explore not only the effects of variables on brand loyalty but also the interrelationships among variables and mediation effects. Moreover, most studies have only investigated the effects of antecedents on brand loyalty but have ignored the effects on attitudinal and behavioral loyalty. Since my findings suggest that drivers of brand loyalty may have different effects on attitudinal and behavioral loyalty, scholars should investigate the effects of the drivers of brand loyalty on different components of brand loyalty.

4.2 Managerial implications

Providing a brand experience is the first step in creating brand loyalty (Foroudi et al., 2018), and managing brand experience is a major concern for any brand (Brakus et al., 2009; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016; Schmitt, 1999). Some scholars have found that the effect of brand experience on brand loyalty was partially mediated by brand satisfaction, brand trust, brand love, or brand commitment (Huang, 2017; Ramaseshan & Stein, 2014; Sahin et al., 2011). However, my findings show that the effects of brand experience on attitudinal loyalty are fully mediated by brand satisfaction, trust, and commitment, while its effects on behavioral loyalty are only partially mediated.

Moreover, consistent with the literature, my findings also show that brand experience is strongly related to brand satisfaction. Therefore, brand experience is still a strong driver of behavioral loyalty. Although providing a satisfactory experience (directly or indirectly) is the first step in building brand loyalty, consumers are still highly likely to base their repurchasing decisions on their positive purchasing experience, even though they trust and are highly committed to a brand. This means that a bad purchasing experience may hurt consumers’ relationships with a brand or even turn them away. Companies and managers need to carefully review the entire experience or consumption chain from need recognition, information searches, evaluating alternatives, purchasing decisions, payments, delivery of products, the storage of products, use or consumption of the products, returns and exchanges, repairs and services, and finally disposal of the products, in order to determine whether the brand can provide a satisfactory and unique brand experience. Moreover, since a brand experience’s effect on attitudinal loyalty is fully mediated by brand satisfaction, trust, and commitment, managers must understand that brand experience is more likely to affect attitudinal loyalty through brand satisfaction and commitment.

Kumar et al. (2013) found that brand satisfaction explains approximately 8% of the variance in brand loyalty; therefore, they argue that “satisfaction is often times a necessary but not a sufficient condition to predict loyalty” (p. 258). Oliver (1999, p. 33) also argues that “satisfaction is a necessary step in loyalty formation but becomes less significant as loyalty begins to set through other mechanisms.” However, my findings show that the effect of brand satisfaction on attitudinal loyalty is not mediated by brand trust and commitment, and brand satisfaction has a stronger effect on attitudinal loyalty than other antecedents of brand loyalty, whether it affects brand loyalty separately or together with other variables. Therefore, brand satisfaction may still be a strong and the most essential predictor of attitudinal loyalty, which drives behavioral loyalty.

However, a very surprising finding revealed in this study is that brand satisfaction has a strong, negative, direct effect on behavioral loyalty when the four antecedents affect brand loyalty jointly. This surprising finding may be the result of combined effects of four drivers of brand loyalty. Although brand satisfaction has a strong, negative, direct effect on behavioral loyalty, it also has a strong, positive, indirect effect on behavioral loyalty. Therefore, the effect of brand satisfaction on behavioral loyalty may be mediated by brand commitment and attitudinal loyalty. When consumers are highly committed to a brand, emotional attachment and the desire to maintain a relationship with a brand matter more than does brand satisfaction. Even though consumers may not be very satisfied with the brand, their emotional attachment and continuance commitment can still cement their relationship with the brand. Therefore, they may by highly tolerant of dissatisfaction. Moreover, consumers may have a higher level of expectations and the degree of brand satisfaction may decline as time goes on. This does not mean that managers should pay more attention to brand commitment instead of brand satisfaction. Satisfying consumers is still the top priority of managers and key driver of attitudinal loyalty, which is positively related to behavioral loyalty.

Consumers will not trust and commit to a brand if they are not satisfied with it. Moreover, even loyal consumers may leave a company, avoid it, and even try to punish it when they are not satisfied with its products and customer services (Grégoire et al., 2009; Kucuk, 2021; Zhang & Laroche, 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). As a result, companies must try to satisfy their customers, especially those who have not built a committed relationship with a company or brand, because brand satisfaction is a critical predictor of brand loyalty for them (Garbarino & Johnson, 1999). First, companies or managers need to understand what the drivers of brand satisfaction are for their brands or products. These drivers may be product (perceived) quality, product value, brand image/equity, design, etc., depending on the market positioning of the brand and characteristics of the product.

Next, companies and managers need to evaluate brand satisfaction regularly by using internet, telephone, or social media. They also need to encourage consumers to complain via different sources, such as telephone, e-mail, or social media. Without proper complaint methods, many unhappy consumers may not communicate with the company but instead share their opinions and experiences on social media, damaging the brand’s image and reputation. Moreover, companies should pay more attention to cumulative satisfaction, which is defined as consumers’ overall evaluation of a product or service over time (Anderson et al., 1994; Johnson et al., 1995) instead of transaction-specific satisfaction, which is based on a consumer’s evaluation of his or her experience with a particular product or service (Olsen & Johnson, 2003), because cumulative satisfaction has a stronger effect on behavioral and intentional outcomes (Anderson et al., 1997; Homburg et al., 2005; Olsen & Johnson, 2003). Therefore, companies and managers should try to keep consumers satisfied long-term.

In accordance with the literature, my findings show that brand trust is positively related to both brand commitment and loyalty. In contrast to the study of Pan et al. (2012), which found brand trust to be the most important driver of brand loyalty, my findings show that brand trust is not the most important driver of brand loyalty when compared to brand experience, satisfaction, and commitment, regardless of whether it separately affects brand loyalty or if it has an effect in combination with other variables.

Moreover, since its direct effect on attitudinal loyalty is not significant and its direct effect on behavioral loyalty is fully mediated by commitment, companies and managers should pay more attention to brand commitment. By no means does my study suggest that brand trust is not important; brand trust is still an essential ingredient in relationship marketing (Palmatier et al., 2006; Sirdeshmukh et al., 2002) and may serve as a link between brand satisfaction and commitment. Without a satisfied experience, especially cumulative satisfaction, customers may not trust a brand, as customers are reluctant to commit to a company or brand if they do not trust it (Aurier & N’Goala, 2010). Companies and managers not only need to offer products with good quality and/or good value, but they also to demonstrate the company’s benevolence, integrity, and honesty (Aurier & N’Goala, 2010). In today’s digital age, e-commerce is growing rapidly, and it accounted for about 10% of total retail trade in 2018 (The U.S. Bureau of Census, 2020). Therefore, customers may trust a brand without having had any direct experience with it because they can see ratings and reviews about a brand online.

Consistent with the literature finding that consumers who are committed to a brand are more loyal to it (Aurier & N’Goala, 2010; Belaid & Behi, 2011; Huang, 2014; Thomson et al., 2005; Nyadzayo et al., 2018; Pedeliento et al., 2016; Ramaseshan & Stein, 2014), my findings also show that brand commitment has a strong effect on behavioral loyalty but not on attitudinal loyalty. The surprisingly insignificant effect on attitudinal loyalty may be the combined effect of these four antecedents, especially brand satisfaction, which has the strongest effect on attitudinal loyalty.

My findings also show that brand commitment can mediate, at least partially, the effects of brand experience, satisfaction, and trust on attitudinal loyalty and behavioral loyalty. However, since brand commitment does not fully mediate the effects of brand experience, satisfaction, and trust, brand loyalty is not the only result of brand commitment but rather the combined effects of these four major antecedents (in this paper).

Moreover, scholars have also found that highly-committed customers are less likely to accept offers from competitors (Ahluwalia et al., 2000, 2001; Swaminathan et al., 2007). Zhang et al. (2020) found that although brand love can exacerbate negative emotions following product or service failure, it can also alleviate the effect of negative emotions on retaliation intention. Therefore, developing a strong brand commitment on the part of customers should be a top priority for a business firm. First, the company should personalize and individualize the brand to attract consumers with similar self-concepts, because consumers prefer to incorporate a brand into their self-concept and express their own self through the purchase and use of a brand (Sirgy, 1982).

To enhance self-congruency, companies and managers can co-create values with consumers. For example, they can increase consumers’ involvement by introducing a new product with consumers. They can also use social media websites or apps to encourage consumers to share their opinions and comments. Second, the company should offer comfort, empathy (e.g., by offering caring and individualized attention to customers), and responsiveness (e.g., willingness to help customers) to consumers. Third, companies can also use brand loyalty programs to build both emotional attachment and continuing commitment, because those can serve as reminders of repurchase opportunities that can reduce the purchasing effort, encourage habitual purchases, or reward repurchasing behavior (Henderson et al., 2011) and show consumers that the company values and rewards their long-term patronage and loyalty. However, since brand commitment is not the only driver of brand loyalty, managers also need to pay attention to brand experience, trust, and satisfaction.

4.3 Limitations and future studies

This study has some limitations. First, it focuses on physical goods only and does not investigate how antecedents affect brand loyalty in service contexts. This study did not include services in its scope because brand experiences with physical goods differ from those with services. The brand experiences are more complicated for services than for physical goods, since services have certain unique characteristics (e.g., intangibility, variability, inseparability, and perishability) and require more interpersonal interaction and communication (Mosley, 2007). Nysveen et al. (2013) found that the brand experience scale differs between physical goods and services, and that relational experience is very important for services. Moreover, the brand satisfaction formation processes for physical goods are also different from those for services (Halstead et al., 1994; Szymanski & Henard, 2001). Future studies should investigate how antecedents influence brand loyalty in service contexts. Second, although the current study is based on a wide range of industries, consumer electronics and appliances are the most represented industry (37%), and Apple is the most represented brand (12.2%). Future studies should test the effects of these antecedents in less-represented industries (e.g., home furniture, tools, shampoos, and laundry detergents, etc.). Moreover, since some companies such Apple and Sony also offer many services, this study also is partially based on services. Third, this study is based on data from U.S. consumers; future studies should investigate the effects of those antecedents in different countries and cultures, especially in rarely studied countries in Latin America, the Middle East, and Africa. Fourth, only four major antecedents are included in this study. Therefore, future studies should investigate the effects of more antecedents, since combinations of different predictors may have different effects on brand loyalty (Russo et al., 2016). Lastly, although the chain effect from brand experience to satisfaction to trust to commitment may be applied to different industries because it has received ample evidence in the literature, the mediation effects found in the study may not be applied to specific industries.

5 Conclusion

This study shows that brand experience, satisfaction, trust, and commitment can affect brand loyalty jointly, and that brand loyalty is not the result of any single variable. However, these four antecedents have different effects on brand loyalty when they affect brand loyalty, either jointly or separately. Specifically, when they affect brand loyalty jointly, their effects on brand loyalty can be mediated, at least partially. Brand satisfaction is the most important driver of attitudinal loyalty, and brand commitment is the most important driver of behavioral loyalty, regardless of whether these four antecedents affect brand loyalty jointly or separately.

References

Aaker, D. A. (1991). Managing brand equity. The Free Press.

Ahluwalia, R., Burnkrant, R. E., & Unnava, H. R. (2000). Consumer response to negative publicity: The moderating role of commitment. Journal of Marketing Research, 37(2), 203–214.

Ahluwalia, R., Unnava, H. R., & Burnkrant, R. E. (2001). The moderating role of commitment on the spillover effect of marketing communications. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(4), 458–470.

Albert, N., Merunka, D., & Valette-Florence, P. (2008). When consumers love their brands: Exploring the concept and its dimensions. Journal of Business Research, 61(10), 1062–1075.

Algesheimer, R., Dholakia, U. M., & Herrmann, A. (2005). The social influence of brand community: Evidence from European car clubs. Journal of Marketing, 69(3), 19–34.

Anderson, E. W., Fornell, C., & Lehmann, D. R. (1994). Customer satisfaction, market share, and profitability: Findings from Sweden. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 53–66.

Anderson, E. W., Fornell, C., & Rust, R. T. (1997). Customer satisfaction, productivity, and profitability: Differences between goods and services. Marketing Science, 16(2), 129–145.

Andreini, D., Pedeliento, G., Zarantonello, L., & Solerio, C. (2018). A renaissance of brand experience: Advancing the concept through a multi-perspective analysis. Journal of Business Research, 91, 123–133.

Aron, A., & Westbay, L. (1996). Dimensions of the prototype of love. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 535.

Atulkar, S. (2020). Brand trust and brand loyalty in mall shoppers. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 38(3), 559–572.

Aurier, P., & N’Goala, G. (2010). The differing and mediating roles of trust and relationship commitment in service relationship maintenance and development. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 38(3), 303–325.

Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1998). On the evaluation of structure equation models. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 16(1), 74–94.

Baldinger, A. L., & Rubinson, J. (1996). Brand loyalty: The link between attitude and behavior. Journal of Advertising Research, 36(6), 22–35.

Baldwin, M. W., Keelan, J. P. R., Fehr, B., Enns, V., & Koh-Rangarajoo, E. (1996). Social-cognitive conceptualization of attachment working models: Availability and accessibility effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 94–109.

Belaid, S., & Behi, A. T. (2011). The role of attachment in building consumer-brand relationships: An empirical investigation in the utilitarian consumption context. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 20(1), 37–47.

Boulding, W., Kalra, A., Staelin, R., & Zeithaml, V. A. (1993). A dynamic process model of service quality: From expectations to behavioral intentions. Journal of Marketing Research, 30(1), 7–27.

Bove, L., & Mitzifiris, B. (2007). Personality traits and the process of store loyalty in a transactional prone context. Journal of Services Marketing, 21(7), 507–519.

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss (Vol. 1). Basic Books.

Brakus, J. J., Schmitt, B. H., & Zarantonello, L. (2009). Brand experience: What is it? How is it measured? Does it affect loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 73(3), 52–68.

Chandrashekaran, M., Rotte, K., Tax, S. S., & Grewal, R. (2007). Satisfaction strength and customer loyalty. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(1), 153–163.

Chaudhuri, A. (1995). Brand equity or double jeopardy? Journal of Product and Brand Management, 4(1), 26–32.

Chaudhuri, A., & Holbrook, M. B. (2001). The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 81–93.

Chiou, J. S., & Droge, C. (2006). Service quality, trust, specific asset investment, and expertise: Direct and indirect effects in a satisfaction-loyalty framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(4), 613–627.

Davis-Sramek, B., Droge, C., Mentzer, J. T., & Myers, M. B. (2009). Creating commitment and loyalty behavior among retailers: What are the roles of service quality and satisfaction? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 37(4), 440.

Das, G., Agarwal, J., Malhotra, N. K., & Varshneya, G. (2019). Does brand experience translate into brand commitment? A mediated-moderation model of brand passion and perceived brand ethicality. Journal of Business Research, 95, 479–490.

Day, G. S. (1969). A two-dimensional concept of brand loyalty. Journal of Advertising Research, 9(3), 67–76.

De Wulf, K., Odekerken-Schröder, G., & Iacobucci, D. (2001). Investments in consumer relationships: A cross-country and cross-industry exploration. Journal of Marketing, 65(4), 33–50.

Delgado-Ballester, E., & Munuera-Alemán, J. L. (2001). Brand trust in the context of consumer loyalty. European Journal of Marketing, 35(11/12), 1238–1258.

Delgado-Ballester, E., Munuera-Aleman, J. L., & Yague-Guillen, M. J. (2003). Development and validation of a brand trust scale. International Journal of Market Research, 45(1), 35–54.

Dick, A. S., & Basu, K. (1994). Customer loyalty: Toward an integrated conceptual framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22(2), 99–113.

Dodds, W. B., Monroe, K. B., & Grewal, D. (1991). Effects of price, brand, and store information on buyers’ product evaluations. Journal of Marketing Research, 28(3), 307–319.

Eelen, J., Özturan, P., & Verlegh, P. W. (2017). The differential impact of brand loyalty on traditional and online word of mouth: The moderating roles of self-brand connection and the desire to help the brand. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 34(4), 872–891.

Elsäßer, M., & Wirtz, B. W. (2017). Rational and emotional factors of customer satisfaction and brand loyalty in a business-to-business setting. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 32(1), 138–152.

Evanschitzky, H., Ramaseshan, B., Woisetschläger, D. M., Richelsen, V., Blut, M., & Backhaus, C. (2012). Consequences of customer loyalty to the loyalty program and to the company. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(5), 625–638.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388.

Foroudi, P., Jin, Z., Gupta, S., Foroudi, M. M., & Kitchen, P. J. (2018). Perceptional components of brand equity: Configuring the symmetrical and asymmetrical paths to brand loyalty and brand purchase intention. Journal of Business Research, 89, 462–474.

Fournier, S., & Yao, J. L. (1997). Reviving brand loyalty: A reconceptualization within the framework of consumer-brand relationships. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 14(5), 451–472.

Fullerton, G. (2003). When does commitment lead to loyalty? Journal of Service Research, 5(4), 333–344.

Ganesan, S. (1994). Determinants of long-term orientation in buyer–seller relationships. Journal of Marketing, 58(2), 1–19.

Garbarino, E., & Johnson, M. S. (1999). The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. Journal of Marketing, 63(2), 70–87.

Germann, F., Grewal, R., Ross, W. T., & Srivastava, R. K. (2014). Product recalls and the moderating role of brand commitment. Marketing Letters, 25(2), 179–191.

Giovanis, A. (2016). Consumer-brand relationships’ development in the mobile internet market: Evidence from an extended relationship commitment paradigm. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 25(6), 568–585.

Grégoire, Y., Tripp, T. M., & Legoux, R. (2009). When customer love turns into lasting hate: The effects of relationship strength and time on customer revenge and avoidance. Journal of Marketing, 73(6), 18–32.

Gruen, T. W., Summers, J. O., & Acito, F. (2000). Relationship marketing activities, commitment, and membership behaviors in professional associations. Journal of Marketing, 64(3), 34–49.

Gustafsson, A., Johnson, M. D., & Roos, I. (2005). The effects of customer satisfaction, relationship commitment dimensions, and triggers on customer retention. Journal of Marketing, 69(4), 210–218.

Han, H., Nguyen, H. N., Song, H., Chua, B. L., Lee, S., & Kim, W. (2018). Drivers of brand loyalty in the chain coffee shop industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 72, 86–97.

Halstead, D., Hartman, D., & Schmidt, S. L. (1994). Multisource effects on the satisfaction formation process. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22(2), 114–129.

Harris, L. C., & Goode, M. M. (2004). The four levels of loyalty and the pivotal role of trust: A study of online service dynamics. Journal of Retailing, 80(2), 139–158.

He, H., Li, Y., & Harris, L. (2012). Social identity perspective on brand loyalty. Journal of Business Research, 65(5), 648–657.

Henderson, C. M., Beck, J. T., & Palmatier, R. W. (2011). Review of the theoretical underpinnings of loyalty programs. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21(3), 256–276.

Homburg, C., Koschate, N., & Hoyer, W. D. (2005). Do satisfied customers really pay more? A study of the relationship between customer satisfaction and willingness to pay. Journal of Marketing, 69(2), 84–96.

Horppu, M., Kuivalainen, O., Tarkiainen, A., & Ellonen, H. K. (2008). Online satisfaction, trust and loyalty, and the impact of the offline parent brand. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 17(6), 403–413.

Hsiao, C. H., Shen, G. C., & Chao, P. J. (2015). How does brand misconduct affect the brand–customer relationship? Journal of Business Research, 68(4), 862–866.

Huang, C. C. (2017). The impacts of brand experiences on brand loyalty: Mediators of brand love and trust. Management Decision, 55(5), 915–934.

Iglesias, O., Markovic, S., & Rialp, J. (2019). How does sensory brand experience influence brand equity? Considering the roles of customer satisfaction, customer affective commitment, and employee empathy. Journal of Business Research, 96, 343–354.

Iglesias, O., Singh, J. J., & Batista-Foguet, J. M. (2011). The role of brand experience and affective commitment in determining brand loyalty. Journal of Brand Management, 18(8), 570–582.

Jacoby, J., & Chesnut, R. W. (1978). Brand loyalty: Measurement and management. New York: Wiley.

Javed, M. K., & Wu, M. (2020). Effects of online retailer after delivery services on repurchase intention: An empirical analysis of customers’ past experience and future confidence with the retailer. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 54, 101942.

Jin, N., Line, N. D., & Merkebu, J. (2016). The impact of brand prestige on trust, perceived risk, satisfaction, and loyalty in upscale restaurants. Journal of Hospitality Marketing and Management, 25(5), 523–546.

Johnson, M. D., Anderson, E. W., & Fornell, C. (1995). Rational and adaptive performance expectations in a customer satisfaction framework. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(4), 695–707.

Karjaluoto, H., Munnukka, J., & Kiuru, K. (2016). Brand love and positive word of mouth: The moderating effects of experience and price. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 25(6), 527–537.

Keller, K. L. (2005). Branding shortcuts: Choosing the right brand elements and leveraging secondary associations will help marketers build brand equity. Marketing Management, 14(5), 18.

Khamitov, M., Wang, X., & Thomson, M. (2019). How well do consumer-brand relationships drive customer brand loyalty? Generalizations from a meta-analysis of brand relationship elasticities. Journal of Consumer Research, 46(3), 435–459.

Khan, I., Hollebeek, L. D., Fatma, M., Islam, J. U., & Rahman, Z. (2020). Brand engagement and experience in online services. Journal of Services Marketing, 34(2), 163–175.

Kleine, R. E., III., Kleine, S. S., & Kernan, J. B. (1993). Mundane consumption and the self: A social-identity perspective. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2(3), 209–235.

Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22.

Kucuk, S. U. (2021). Developing a theory of brand hate: Where are we now? Strategic Change, 30(1), 29–33.

Kuikka, A., & Laukkanen, T. (2012). Brand loyalty and the role of hedonic value. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 21(7), 529–537.

Kumar, V., Dalla Pozza, I., & Ganesh, J. (2013). Revisiting the satisfaction–loyalty relationship: Empirical generalizations and directions for future research. Journal of Retailing, 89(3), 246–262.

Lee, D., Moon, J., Kim, Y. J., & Mun, Y. Y. (2015). Antecedents and consequences of mobile phone usability: Linking simplicity and interactivity to satisfaction, trust, and brand loyalty. Information and Management, 52(3), 295–304.

Lemon, K. N., & Verhoef, P. C. (2016). Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. Journal of Marketing, 80(6), 69–96.

Li, M. W., Teng, H. Y., & Chen, C. Y. (2020). Unlocking the customer engagement-brand loyalty relationship in tourism social media: The roles of brand attachment and customer trust. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 44, 184–192.

Liu-Thompkins, Y., & Tam, L. (2013). Not all repeat customers are the same: Designing effective cross-selling promotion on the basis of attitudinal loyalty and habit. Journal of Marketing, 77(5), 21–36.

Malär, L., Krohmer, H., Hoyer, W. D., & Nyffenegger, B. (2011). Emotional brand attachment and brand personality: The relative importance of the actual and the ideal self. Journal of Marketing, 75(4), 35–52.

Matzler, K., Pichler, E., Füller, J., & Mooradian, T. A. (2011). Personality, person–brand fit, and brand community: An investigation of individuals, brands, and brand communities. Journal of Marketing Management, 27(9–10), 874–890.

McConnell, J. D. (1968). The development of brand loyalty: An experimental study. Journal of Marketing Research, 5(1), 13–19.

Menidjel, C., Benhabib, A., & Bilgihan, A. (2017). Examining the moderating role of personality traits in the relationship between brand trust and brand loyalty. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 26(6), 631–649.

Miquel-Romero, M. J., Caplliure-Giner, E. M., & Adame-Sánchez, C. (2014). Relationship marketing management: Its importance in private label extension. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 667–672.

Michell, P., Reast, J., & Lynch, J. (1998). Exploring the foundations of trust. Journal of Marketing Management, 14(1–3), 159–172.

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38.

Moorman, C., Deshpande, R., & Zaltman, G. (1993). Factors affecting trust in market research relationships. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 81–101.

Mosley, R. W. (2007). Customer experience, organisational culture and the employer brand. Journal of Brand Management, 15(2), 123–134.

Muniz, A. M., & Oguinn, T. C. (2001). Brand community. Journal of Consumer Research, 27(4), 412–432.

Muniz, F., Guzmán, F., Paswan, A. K., & Crawford, H. J. (2019). The immediate effect of corporate social responsibility on consumer-based brand equity. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 28(7), 864–879.

Nadeem, W., Khani, A. H., Schultz, C. D., Adam, N. A., Attar, R. W., & Hajli, N. (2020). How social presence drives commitment and loyalty with online brand communities? the role of social commerce trust. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, 102136.

Nguyen, H. T., Zhang, Y., & Calantone, R. J. (2018). Brand portfolio coherence: Scale development and empirical demonstration. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 35(1), 60–80.

Nyadzayo, M. W., Matanda, M. J., & Rajaguru, R. (2018). The determinants of franchise brand loyalty in B2B markets: An emerging market perspective. Journal of Business Research, 86, 435–445.

Nysveen, H., Pedersen, P. E., & Skard, S. (2013). Brand experiences in service organizations: Exploring the individual effects of brand experience dimensions. Journal of Brand Management, 20(5), 404–423.

Oliver, R. L. (1993). Cognitive, affective, and attribute bases of the satisfaction response. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(3), 418–430.

Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63(4_suppl1), 33–44.

Olsen, L. L., & Johnson, M. D. (2003). Service equity, satisfaction, and loyalty: From transaction-specific to cumulative evaluations. Journal of Service Research, 5(3), 184–195.

Palmatier, R. W., Dant, R. P., Grewal, D., & Evans, K. R. (2006). Factors influencing the effectiveness of relationship marketing: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marketing, 70(4), 136–153.

Palmatier, R. W., Jarvis, C. B., Bechkoff, J. R., & Kardes, F. R. (2009). The role of customer gratitude in relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 73(5), 1–18.

Pan, Y., Sheng, S., & Xie, F. T. (2012). Antecedents of customer loyalty: An empirical synthesis and reexamination. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 19(1), 150–158.

Pansari, A., & Kumar, V. (2017). Customer engagement: The construct, antecedents, and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(3), 294–311.

Park, C. W., MacInnis, D. J., Priester, J., Eisingerich, A. B., & Iacobucci, D. (2010). Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: Conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. Journal of Marketing, 74(6), 1–17.

Park, E., Kim, K. J., & Kwon, S. J. (2017). Corporate social responsibility as a determinant of consumer loyalty: An examination of ethical standard, satisfaction, and trust. Journal of Business Research, 76, 8–13.

Paulssen, M. (2009). Attachment orientations in business-to-business relationships. Psychology & Marketing, 26(6), 507–533.

Paulssen, M., Roulet, R., & Wilke, S. (2014). Risk as moderator of the trust-loyalty relationship. European Journal of Marketing, 48(5/6), 964–981.

Pedeliento, G., Andreini, D., Bergamaschi, M., & Salo, J. (2016). Brand and product attachment in an industrial context: The effects on brand loyalty. Industrial Marketing Management, 53, 194–206.

Picón, A., Castro, I., & Roldán, J. L. (2014). The relationship between satisfaction and loyalty: A mediator analysis. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 746–751.

Ramaseshan, B., & Stein, A. (2014). Connecting the dots between brand experience and brand loyalty: The mediating role of brand personality and brand relationships. Journal of Brand Management, 21(7–8), 664–683.

Rather, R., & Sharma, J. (2016). Brand loyalty with hospitality brands: The role of customer brand identification, brand satisfaction and brand commitment. Pacific Business Review International, 1(3), 76–86.

Ravald, A., & Grönroos, C. (1996). The value concept and relationship marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 30(2), 19–30.

Reichheld, F. F. (1996). The loyalty effect. Harvard Business School Press.

Reichheld, F. F. (2003). The one number you need to grow. Harvard Business Review, 81(12), 46–55.

Rialti, R., Zollo, L., Pellegrini, M. M., & Ciappei, C. (2017). Exploring the antecedents of brand loyalty and electronic word of mouth in social-media-based brand communities: Do gender differences matter? Journal of Global Marketing, 30(3), 147–160.

Russo, I., Confente, I., Gligor, D. M., & Autry, C. W. (2016). To be or not to be (loyal): Is there a recipe for customer loyalty in the B2B context? Journal of Business Research, 69(2), 888–896.

Sahin, A., Zehir, C., & Kitapçı, H. (2011). The effects of brand experiences, trust and satisfaction on building brand loyalty; an empirical research on global brands. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 24, 1288–1301.

Schmitt, B. (1999). Experiential marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 15(1–3), 53–67.

Schultz, D. E., & Block, M. P. (2012). Rethinking brand loyalty in an age of interactivity. IUP Journal of Brand Management, 9(3), 21.

Sirgy, M. J. (1982). Self-concept in consumer behavior: A critical review. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(3), 287–300.

Sirdeshmukh, D., Singh, J., & Sabol, B. (2002). Consumer trust, value, and loyalty in relational exchanges. Journal of Marketing, 66(1), 15–37.

Szymanski, D. M., & Henard, D. H. (2001). Customer satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29(1), 16.

Swaminathan, V., Page, K. L., & Gürhan-Canli, Z. (2007). “My” brand or “our” brand: The effects of brand relationship dimensions and self-construal on brand evaluations. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(2), 248–259.

Swaminathan, V., Stilley, K. M., & Ahluwalia, R. (2008). When brand personality matters: The moderating role of attachment styles. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(6), 985–1002.

The U.S. Bureau of Census. (2020). E-Stats 2018: Measuring the Electronic Economy, May 21, 2020, Accessed on Feb 20, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/econ/2018-e-stats.html

Thomson, M., MacInnis, D. J., & Park, C. W. (2005). The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 15(1), 77–91.

Trivedi, S. K., & Yadav, M. (2020). Repurchase intentions in Y generation: Mediation of trust and e-satisfaction. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 38(4), 401–415.

Tse, D. K., & Wilton, P. C. (1988). Models of consumer satisfaction formation: An extension. Journal of Marketing Research, 25, 204–212.

Tucker, W. T. (1964). The development of brand loyalty. Journal of Marketing Research, 1(3), 32–35.

van der Westhuizen, L. M. (2018). Brand loyalty: Exploring self-brand connection and brand experience. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 27(2), 172–184.

Voss, G. B., Godfrey, A., & Seiders, K. (2010). How complementarity and substitution alter the customer satisfaction–repurchase link. Journal of Marketing, 74(6), 111–127.

Watson, G. F., Beck, J. T., Henderson, C. M., & Palmatier, R. W. (2015). Building, measuring, and profiting from customer loyalty. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(6), 790–825.

Zhang, C., & Laroche, M. (2020). Brand hate: A multidimensional construct. Journal of Product and Brand Management, Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-11-2018-2103

Zhang, Y., Zhang, J., & Sakulsinlapakorn, K. (2020). Love becomes hate? or love is blind? Moderating effects of brand love upon consumers’ retaliation towards brand failure. Journal of Product and Brand Management, 30(3), 415–432.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, B. How brand experience, satisfaction, trust, and commitment affect loyalty: a reexamination and reconciliation. Ital. J. Mark. 2022, 203–231 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43039-021-00042-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43039-021-00042-9