Abstract

Resilience is a process that involves positive adaptation to trauma through protective factors. How resilience differs based on race and ethnicity is less known for youths in residential treatment programs. This study collected views from culturally diverse youths in a residential program on ways they have overcome adversity. The findings were used to develop a culturally informed screen of activities related to resilience for youths in residential programs. This study included 32 youths ages 12–18 residing in a residential program; 66% were male, 34.5% White, 25% African American, 21.9% Latinx, 15.6% more than one race, and 3.1% American Indian. Youths completed resilience measures and participated in focus groups that were conducted according to race and ethnicity. Youths answered two questions: (1) What has helped you overcome some of the difficult challenges you have faced in life? (2) When you think about hard times that you have gone through, what family and community traditions have helped you? Racial and ethnic similarities and differences in the themes and activities are reported. Preliminary scale design of the resilience screen is also included. Convergence of the findings with the existing literature on youth resilience, limitations, and future directions are discussed. The study has implications for further development of a culturally informed measure of resilience for youths.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Youths in residential programs have high rates of exposure to adversity such as trauma (Bettman et al., 2011; Briggs et al., 2012; Seifert et al., 2015), and approximately one-third have posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Boyer et al., 2009; Mueser & Taub, 2008). Yet, resilience—a process that involves positive adaptation to trauma through protective factors (Kim-Cohen, 2007)—lacks supporting research for youths in residential programs. Resilience involves two components: (1) exposure to risk factors and (2) subsequent positive adaptation through protective factors that mitigate risks (Kim-Cohen, 2007). Ungar (2013) argues resilience differs based on the amount of risk exposure, context, and culture, and the environment is more critical in child development than the child’s traits with regard to resilience. Therefore, understanding protective factors from within a cultural context is critical to inform clinical interventions and promote resilience in youths receiving residential services.

To better serve youths across the United States, trauma-informed services (United States Health and Human Services (USDHHS), 2014) are recommended to reduce vulnerability in youths while they are in care. Building resilience through protective factors is an important aspect of trauma-informed care. Protective factors can mitigate the impact risk factors, such as childhood maltreatment, have on developmental outcomes (Cohen, 2007). Additionally, combining trauma-informed care with cultural humility—which involves “a deeper understanding of cultural differences to improve the way vulnerable groups are treated and researched” (p.252) (Yeager & Bauer-Wu, 2013)—can improve the quality of services for youths (Ranjbar et al., 2020), especially youths from underrepresented cultures.

Determining adverse childhood experiences (ACEs; Felitti et al., 1998) and trauma symptoms in youths in residential programs from a cultural perspective is challenging. While many residential programs traditionally use ACEs to assess for exposure to traumatic events, this checklist does not include stressors such as racism and discrimination that minority youths may encounter. Inconsistency in reporting trauma exposure can also be as high as 30 to 40% (MacDonald et al., 2016) due to the sensitivity of the topic (McKinney et al., 2009). Additionally, youths from some cultures may be reluctant to share intimate hardships with others outside of their family (Summerfield, 2000). Endorsement of symptoms associated with trauma can also differ based on race and ethnicity. A cross-cultural review of PTSD (Hinton & Lewis-Fernandez, 2011) indicated diagnostic criteria for PTSD may not be calibrated to specific cultural groups. These findings indicated that although overall prevalence rates of PTSD in the United States across cultures do not differ, endorsement of PTSD symptoms may. For example, reported symptoms may be higher for Latinx, African Americans, and American Indians because of the effects of racism and discrimination (Hinton & Lewis-Fernandez, 2011). Therefore, it is important to recognize that youths placed in residential programs could report symptoms associated with trauma differently based on their race and ethnicity.

Although many studies demonstrate that youths exposed to adversity will experience increased risk for later negative outcomes (e.g., traumatic stress, suicidality) (Mueser & Taub, 2008), resilience—or positive adaptation after adversity (Kim-Cohen, 2007)—is possible. Resilient functioning can include factors such as intelligence, supportive relationships, safe communities, planning, and self-regulation (Masten, 2001; Williams et al., 2001). For example, problem-solving skills have been found to contribute to resilience (Williams et al., 2001). Further, resilience, self-efficacy, and social support mediate stressful situations and problem-solving (Li et al., 2018). In a study of adults exposed to childhood maltreatment, resilience was related to peer relationships in adolescence and the quality of adult friendships (Collishaw et al., 2007). Improving the screening of resilience via a culturally informed lens could further protect minority youths from the harmful effects of trauma.

From a cultural perspective, racial identity is a protective factor against discrimination for marginalized minorities (Zimmerman et al., 2013). Heid et al. (2022) found strategies that improved resilience for youths from Indigenous cultures were future orientation, cultural pride, and interacting with community members. The Indigenous traditional knowledge and continuity of their culture were all resilience pathways to reducing stressors, while stressors that had the most negative effects were family instability, loss of cultural identity, and substance use. Similar themes of social support, prayer, or respective cultural faith practices were also identified as resilience factors in a study by Killgore et al. (2020). The relationship between trauma and resilience from a cultural standpoint is not straightforward, however. For example, circumstances such as discrimination can drive a youth to adopt a “striving persistent behavioral style (SPBS),” a resilience factor that can push a youth to succeed in one domain such as academics but also create a detrimental hindrance in another such as physical and mental wellbeing (Doan et al., 2022).

Gaining a better understanding of factors that mitigate adversities such as trauma exposure and symptoms in youths placed in residential programs, from a cultural standpoint, can aid in the development of instruments that can inform strength-based services. Unfortunately, few resilience instruments have been developed with input from cultural minorities (Ungar, 2013). To address this gap in the field, we used participatory action research (PAR) which is a research approach designed to promote social change (Institute of Development Studies, 2024). PAR includes persons, who are most affected by the problem, in the research process to identify solutions that are beneficial for them (Cargo & Mercer, 2008; Institute of Development Studies, 2024; Minkler et al., 2003). The purpose of this qualitative study was to provide a better understanding from youths in residential programs on ways they have overcome adversity, cultural customs and traditions that helped them, and how these approaches were similar and different based on youths’ race/ethnicity. This information was then used to inform the development of a screening instrument on resilience that could be coupled with trauma screening to better inform treatment planning for youths entering residential programs. This consisted of activities that helped youths transform their lives from risks to resilience (Rutter, 2007) from a cultural perspective. The aims of this study were (1) to collect views from youths in a residential program on ways they have overcome adversity in their lives, (2) to examine how these views compared based on factors related to race and ethnicity, and (3) to develop a brief culturally informed screen of resilience that could be used for youths in residential programs.

Method

Participants

Participants were from a large residential program in the Midwest United States. The study was approved by the Boys Town National Research Hospital Institutional Review Board, and parent permissions and youth assents were obtained prior to the study. The study included 32 youths, ages 12.2 to 18.2 years with a mean of 15.8 (SD = 1.56); 65.6% were male, with 34.5% White, 25% African American, 21.9% Latinx, 15.6% more than one race, and 3.1% American Indian. Prior exposure rates to childhood adversity were as follows: 38.7% emotional abuse, 16.1% physical abuse, 3.2% sexual abuse, 16.1% exposure to domestic violence, 45.2% substance use in the family, 16.1% mental illness in the family, 45.2% witnessing parent marital discord, 9.7% criminal parent, 19.4% neglect, 37.5% had been adopted, and 31.3% were living below the poverty level. At the time of admission into the program, 46.7% of the youths had endorsed items of posttraumatic stress on the Brief Trauma Symptom Screen for Youth (Tyler et al., 2019). Youths also completed the 14-Item Resilience Scale-14 (RS-14; Wagnild, 2009) that included items such as “I can get through difficult times because I’ve experienced difficulty before” rated on a seven-point scale from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 7 = Strongly Agree. The internal consistency was α = 0.90. The mean on the RS-14 was 73.26 (SD = 13.9, range 30–92, skew = 1.34, kurtosis = 2.4) with 6.5% of youths reporting very low resilience, 38.7% low, 19.4% moderate, 32.3% moderately high, and 3.2% very high. Ratings on the RS-14 did not differ based on sex (p = 0.749) or race/ethnicity (p = 0.460) (see Table 1). All of the participants in the study were residing in a trauma-informed (see USDHHS, 2014) residential program (see Father Flanagan’s Boys’ Home, 2015) that implements a modified version (Thompson & Daly, 2015) of the evidence-based Teaching-Family Model (TFM; Wolf et al., 1995) in family-style group homes.

Participatory Action Research

Participatory action research (PAR) was used to target resilience for youths in this residential program. Key concepts of PAR (see Institute of Development Studies, 2024) were included in the design of the study: (a) emphasis on having direct benefits for the youths, (b) facilitating a process that empowered the youths to determine the solutions, (c) including youths in the analysis and evaluation of the research results, and (d) translating the results into change that improves services for youths in residential programs. To emphasize the benefits for youths in the residential program, three homogenous groups of both boys and girls of the same races/ethnicities and one group of youths from combined races/ethnicities were assembled. Groups were comprised of the following: Group One = eight White youths, Group Two = nine African American youths, Group Three = seven Latinx youths, Group Four = eight youths of different races/ethnicities. To empower youths, “resilience” was explained to them and then they were asked to respond to two questions. Question One was aimed at helping them identify individual factors related to resilience: (1) “What has helped you overcome some of the difficult challenges you have faced in life?” Question Two was aimed at helping them identify cultural, family, and community factors related to resilience (2) “When you think about hard times you have gone through, what family and community traditions have helped you?” To facilitate an empowering process, focus groups, using a modified Nominal Group Technique (NGT; see Trout & Epstein, 2010), provided an opportunity for youths to gain an understanding of how they overcame difficult challenges/adversity in their lives.

Focus groups were facilitated by the principal investigator (PI) with prior experience conducting focus groups using NGT (Tyler et al., 2014, 2018) and a Research Scientist who received training on the NGT. NGT is a structured focus group procedure that combines both qualitative and quantitative methods to collect client feedback in an efficient manner (Tuffrey-Wijne et al., 2007). NGT provides a replicable process to gather information for developing client-oriented interventions (Nelson et al., 2002; Tuffrey-Wijne et al., 2007). The same procedure was used for all 90-min sessions. First, a script was developed to assure consistency among each focus group session. Second, the purpose and expectations of the focus group were explained to participants. Third, participants were given a brief explanation of resilience to provide them with the purpose of the study. Fourth, participants were provided an overview of the process of the focus group and allowed to ask questions.

A modified six-step NGT process was used for data collection and preliminary analyses. In step one, youths were asked Question One, “1) What has helped you overcome some of the difficult challenges you have faced in life?” Participants were instructed to take 10 min to write down as many ideas as possible on index cards to Question One, writing one idea on each card. In step two, the cards were collected. The four groups of participants generated a total of 181 ideas for Question One. Ideas were randomly read out loud and written on a display screen for participants. Step three included a discussion with participants to clarify the meaning of the ideas, to combine similar or duplicate ideas, or to add new ones. In step four, participants were included in the analyses of the results by voting on the most important ideas from the list. Each participant was given five new index cards and asked to choose the five ideas they thought were the most important and place the idea number in the upper left-hand corner of the index card, along with the identifying phrase from the list. Step five involved each participant ranking the five ideas they found most important by assigning 1 to 5 points to each of the five selected ideas based on highest priority. Each participant scored the idea of highest priority with a score of 5 points, the second highest idea received 4 points, third highest idea 3 points, fourth highest idea 2 points, and fifth highest idea 1 point. Finally, in step six, the note cards were recollected and aggregated, so the most important themes could be identified. The same six-step process was then repeated with Question Two, (2) “When you think about hard times you have gone through, what family and community traditions have helped you?” The four groups of participants generated a total of 148 ideas for Question 2. These results were then further analyzed to determine themes that could be used for the development of a brief resilience screen.

Data Analysis

A six-step process was used to determine themes for both questions. First, the ideas generated by the four focus groups were combined into two lists of the rated items for Question One and the rated items for Question Two based on the votes assigned by the focus group participants. Second, the lists were presented to research staff familiar with the study to independently group the ideas into the themes for each question. The coded themes for each item were then discussed by the group to check the agreement. Disagreements were reconciled by discussion between the project staff to make a final determination. Both lists were coded using MAXQDA 2022 (VERBI Software, 2021). Third, to check reliability, the original list of ideas was coded by two new researchers, who were blinded to the original coding. Both researchers were asked to independently assign the themes that were identified by the research team in step two to the list of participant ideas. Fourth, the values for the themes were calculated by summing the points assigned by the participants for all the ideas included in each theme. Fifth, the themes were ranked according to the point values to determine the order of priority. Finally, comparisons of cases and groups (see MAXQDA; VERBI Software, 2021) were used to compare the ranking of themes for both questions between the four groups to examine similarities and differences based on race and ethnicity.

Descriptive statistics, means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis were calculated for the sample. Pearson R correlations and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to determine the relationships between the resilience measures and to compare group differences. Internal consistency using Cronbach’s alpha and principal component analysis was conducted using SPSS version 25 (IBM, 2017). The survey data on the resilience measures were used to establish convergent validity for the newly developed resilience measure.

Results

There were seven themes for Question One that was aimed at identifying individual factors related to resilience (see Table 2). The interrater reliability for Question One was k = 0.95, p < 0.001. Physical activity included “exercise,” “working out,” and playing sports such as “wrestling,” “basketball,” “football,” and “volleyball.” Social support ideas were “talking to a trusted person” such as a friend, staff person, teacher, and therapist. Hobbies included activities such as “cooking,” “building things,” “art,” and “music.” Youth identified “solving problems,” “staying present,” “thinking about the positive,” “taking a shower,” and “sleeping” as coping strategies. Relationships with “Mom,” “grandparents,” and “siblings” were identified as important sources of family support. Faith included “prayer” and “having a relationship with God.” Finally, for self-care, youth shared different ways to treat themselves such as “getting my hair done,” “going shopping,” and buying things they like such as “shoes.”

Comparison of themes based on the race/ethnic groups (see Table 2) showed all four groups ranked hobbies as one of the top five themes. The White group ranked social support the most important, and the only group that did not rate any items for family. The African American group also ranked social support the highest, and ranked physical activity the lowest. The Latinx group ranked faith the highest, and the only group that did not rate items related to self-care. The Combined group of different races/ethnicities ranked physical activity the highest, and the only group that did not rate any items related to faith.

There were 14 themes for Question Two that was aimed at identifying cultural, family, and community factors (see Table 3). The interrater reliability for Question Two was k = 0.91, p < 0.001. Several themes emerged that involved spending time with family during different events and activities such as holidays and memorials (e.g., Christmas, Day of the Dead), vacations, going for car rides, cookouts, family reunions, and family time at home “playing games” and “watching movies.” Playing and watching team sports and doing outdoor activities such as “going fishing” or to the “community pool” were some of the physical activities shared by youth. Youths identified faith-based activities such as “going to church,” “youth groups,” and “sweat lodge,” helping others, and attending larger community events such as “community fairs” and “car shows” as important activities. Youth also shared ideas related to different types of entertainment such as listening to music, “going to concerts,” movies, and watching social media with friends and family. Finally, youths shared specific events where they received social support from friends and family due to an “injury,” “illness,” or “family emergency.”

Comparisons of themes based on race/ethnicity showed the White group ranked holiday festivities/memorials as the highest, and the only group to rank sports and sporting events and getting outdoors as a theme in the top five. The African American group also ranked holidays the highest along with faith, and the only group that ranked helping others in the top five. The Latinx group ranked vacations the highest, and the only group to rank community events (e.g., car shows) in the top five. The combined group ranked car rides (e.g., fast food runs) the highest, and the only group to rank movies and media in the top five.

Resilience Scale Development

For the next phase of the study, the results of the focus groups were used to create a screening questionnaire of the most common healthy activities shared by youth. The questionnaire was constructed with 51 unique participant ideas that made up the 21 themes from the two focus group questions. To pilot the screening instrument, a subset of focus group participants (n = 25) completed the questionnaire. Demographics for the subsample were as follows: 78.3% male, 30.4% White, 26.1% African American, 13.0% Latinx, and 30.4% more than one race, with a mean age of 16.3 (SD = 2.10). Youth were asked to respond to the statement “When I am dealing with bad things in my life, I find it helpful to…” and then rate each item 0 = Not Like Me, 1 = Somewhat Like Me, and 2 = A Lot Like Me. After youths filled out the prototype of the resilience screen, it was discussed in a large group to get their opinions and suggestions on the measure. Youths provided input on the clarity of the items and how useful it would be for new youths coming into the residential program. Some of the items were unclear (e.g., fun runs) and were later omitted. The youths were also asked how many of them believed the resilience screen would be beneficial for new youths who were coming into the residential program. A show of hands indicated that almost 90% (22) of the youths agreed it would be helpful for new youths. Suggestions from the youths were used to refine the resilience measure and determine its usefulness for future youths in the residential program.

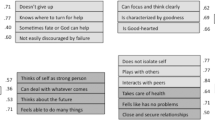

Principal component analysis was used to determine the initial scale structure of the questionnaire. This resulted in the deletion of 10 items from the 51 original to get to a total scale and subscales internal consistencies of α > 0.70. Internal consistency of the 41-item screening questionnaire was α= 0.95 with an overall mean of 46.12, (SD = 18.00, range 11–82, skew = − 0.14, kurtosis = − 0.26, and item mean = 1.12 (SD = 0.44). Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was used to determine the proportion of variance in the variables caused by underlying factors based on a value > 0.50, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was used to determine if factor analysis would be useful based on a p value < 0.05 (IBM, 2021). The results highlighted the overlap in ideas within the themes and sub-themes for Questions One and Two which reduced the number of subscales to eight: (1) physical activity & outdoor recreation, (2) social support, (3) coping strategies, (4) hobbies, (5) family time, (6) faith, (7) self-care and community, and (8) helping others. Items within the themes of social support, faith, coping strategy, and helping others remained unchanged. Family items within themes such as holiday festivities, vacations, family gatherings, car rides, and family time were combined into a family-time subscale. Hobbies, music, and media were combined into hobbies. Physical activity, sports, and outdoor recreation were combined into physical activity and outdoor recreation. Self-care and community were also combined into one subscale. Internal consistencies, means, and standard deviations for the eight subscales are found in Table 4. Total scores on the scale, referred to as the Healthy Activities for Raising Resilient Youth (HARRY), demonstrated good convergent validity with the RS-14 with a significant moderate positive correlation of r = 0.58, p = 0.003. There was not a significant difference for total ratings on the HARRY or subscales based on race/ethnicity F(3, 21) = 0.404, p = 0.751. However, it should be noted that this sample size was small.

Discussion

This study was conducted to seek a better understanding of activities related to resilience according to youths from diverse cultural backgrounds in a residential program. Results to the first question provided overarching themes of individual activities related to overcoming difficult challenges, while the second question provided examples of family and cultural activities that youths found helpful to get through hard times. The results from both questions were used to develop a screen of healthy activities related to resilience (i.e., HARRY). Each of the themes will be discussed to demonstrate convergence with the literature on residential programs, along with cultural implications more generally.

Physical Activity and Outdoor Recreation

Physical activity and outdoor recreation were the highest-rated theme overall and included ideas such as “playing a team sport,” “exercising,” “working out,” and “spending time outdoors” (e.g., camping, hiking). The importance of this theme is further supported by previous research demonstrating that general working out, exercise, and increased physical activity are related to emotional resilience and happiness (Dogan, 2015; Richards et al., 2015). Sports training can increase mental toughness and self-efficacy while reducing negative emotions such as anxiety and depression (Cui and Zhang, 2022). Williams and Bryan (2012) reported involvement in extracurricular activities contributed to youths’ resilience and academic success. For youths in residential programs, an intervention that educated youths on healthier eating and physical activity showed promising results with increased involvement in sports, healthy meal preparation, self-esteem, and independent living skills (Green et al., 2022).

The results from our study also parallel previous literature demonstrating the benefits of physical activity across diverse cultures. For example, links between physical activity and cognitive and psychological well-being have been demonstrated in both African American and Latinx youths (Crews et al., 2004; Perrino et al., 2019; Reed et al., 2013). In American Indian youths in the Midwest U.S., involvement in sports and activities was related to prosocial outcomes (LaFromboise et al., 2006), and participation in sports and activities has been encouraged by American Indian Elders in the Southwest US to promote resilience in youths (Kahn et al., 2016). Spending time outdoors and “learning from the natural world” can also improve resilience by fostering a sense of peace and connection and help youths observe cycles of change and regrowth (Heid et al. (2022).

In our study, there were differences noted between groups based on the type of physical activities and settings. African American youths did not identify physical activity as an important individual activity, but they did rank it as a family or community activity that has helped them. Conversely, Latinx youths in our study ranked physical activity as an important individual activity, but not as a family or community activity, although several Latinx youths talked about fun memories of watching their family members play on their softball teams. Engaging in outdoor recreational activities such as going to the swimming pool and lakes was ranked higher by White youths. Youths talked about annual fishing trips that they took with their family. Further exploration is needed to see if interest in physical activity and the relationship to resilience differs culturally for youths based on the type of physical activity, setting, etc.

Social Support

Focus group participants discussed the importance of social support that included “talking to good friends,” “spending one on one time with family members,” and “talking to someone you trust.” This converged with other studies finding that social support such as friends and adults at school (e.g., teachers, coaches) positively predicted resilience, while the inverse of social support through bullying negatively predicted resilience (Zheng et al., 2021). Social support helped youths who experienced adversity (e.g., postwar environments) reappraise their circumstances and see stressful situations as opportunities for growth so they could confront them more confidently (Pejičić et al., 2017). Extreme environmental factors were not the only circumstances where social support was effective. Strong school connections mitigate neighborhood risks such as exposure to community violence (Ernestus & Pelow, 2015). For example, in a small study of African American students from low-income single-parent families, supportive school-based relationships with teachers, counselors, and coaches contributed to their resilience (Williams & Bryan, 2012). For youths in residential programs, helping them identify social support through supportive relationships from adults in school, programs, and community settings is critically important for promoting resilience and reducing traumatic stress (Hagan & Spinazzola, 2013). For example, a study of 213 youths in a residential program found mentoring was related to increased sense of belonging, which in turn mediated resilience (Sulimani-Aidan & Schwartz-Tayri, 2021). Additionally, our prior research has found positive peer relationships are a protective factor against suicide ideation for youths in residential programs with trauma symptoms (Tyler et al., 2022).

Coping

Coping strategies included ideas such as “thinking of something positive,” “trying to problem solve,” “staying in the moment,” “doing something that makes you laugh,” and “changing your body temperature to calm down.” These strategies were ranked as highly beneficial by all three major ethnic/racial groups explored. Problem-solving contributes to the development of resiliency (Williams et al., 2001) and has been an identified protective factor in adolescents exposed to mass traumatic events like war, civil conflicts, and terrorist attacks (Braun-Lewensohn et al., 2009; Dawson et al., 2018; Fayyad et al., 2017). Improving coping skills and self-regulation are important skills to help children in residential programs increase safe behavior and reduce traumatic stress (Hagan & Spinazzola, 2013). In our prior research, problem-solving skills were related to greater decreases in emotional distress from intake to discharge in youth with high trauma symptoms receiving services in a residential program (Tyler et al., 2021). In studies of youths in other cultures, finding solutions and hope for the future (e.g., as described by Aboriginal youth in Australia, Gale & Bolzan, 2013); reframing, normalizing stressors, and focusing on goals (e.g., as described by undocumented Mexican youth in the US, Kam et al., 2018); and thinking positively about challenges (e.g., as described by Middle East refugee youth in Canada, Smith et al., 2021) were all related to resilience. Focus groups conducted with 39 African American youths exposed to community violence identified the ability to persevere, self-regulate, and change to adapt/improve as keys to resilience (Woods-Jaeger et al., 2020). Youths in our study also shared Tip the Temperature (TIP) strategies from dialectical behavior therapy (Linehan, 2020) such as changing body temperature to calm down fast and self-regulate (DBT Tools, 2023).

Hobbies

Hobbies were a theme described by youths that included ideas such as “cooking,” “baking,” “building something,” “listening to music,” and “going to concerts.” Youths in our study were unanimous about music listening as an activity to overcome adversity. Music provides a way for youths to define and express themselves, get through difficult times, and think critically about the world around them (Hess, 2019; Travis, 2013). These benefits are evident across many cultures. For example, a study of Mayan youths in Guatemala found hip-hop music provided cultural resilience by narrating their experience in a way they could identify with, supporting their Mayan language and history (Bell, 2017). Hip-hop and rap can also provide an avenue for Black youths to express personal and societal concerns—particularly when this music is used to promote positive self-esteem and ethnic identity (Payne & Gibson, 2008; Travis & Bowman, 2012). Music can however pose both benefits and challenges. A mixed-method study that used music with youths in a juvenile justice setting found it provided them the opportunity to recognize their abilities, engage in creative group activities, and allowed them to express themselves; however, it also created conflicts, feelings of exclusion, and triggered difficult memories and feelings (Daykin et al., 2017). Therefore, it is important to help youths find healthy, constructive, and prosocial hobbies that can provide them opportunities for self-expression and enjoyment.

Family Time

The family-time domain included ideas such as “playing games,” “watching movies,” “going shopping,” “family vacations,” “road trips,” “family gatherings,” and “cookouts.” Several youths in our study shared how the holidays and traditions were important times to reconnect with family and their cultural identity, which highlighted the value of holidays for quality family time. Youths shared family traditions based on their heritage such as “hiding the pickle” in the Christmas tree. Several of the girls talked about going shopping the day after Thanksgiving with the mothers, grandmothers, etc. Other youths talked about celebrating “not holidays,” by celebrating a holiday on a different day because their parents had to work. Youths were also excited to share traditions about being involved with their family by helping with the BBQ (e.g., smoking meat) or making special dishes during family get-togethers and reunions.

Quality time with family can aid in parental monitoring, bonding, and family cohesion (Willoughby & Hamza, 2011). Support from parents positively predicts resilience, while family conflict negatively predicts resilience in youths (Zheng et al., 2021). The positive impact that spending time together as a family has across cultures is consistent in the literature. A study of Latino youths by Castro et al. (2007) found family bonding was a strong protective factor and associated with youths’ social responsibility (e.g., citizenship) and traditional family values (e.g., maintaining family traditions). For African American youths, family support can buffer the detrimental effects of community violence and lower youths’ risk for general psychological distress (DiClemente et al., 2018; Trask-Tate et al., 2010). Additionally, reduced parental conflict can buffer the effects of neighborhood disadvantage and influence on delinquent behavior (Lei & Beach, 2020). In White youths in a rural community, nurturant and involved parenting reduced the risk for externalizing and internalizing problems during economic hardships (Conger & Conger, 2002). In general, youths from families that are more cohesive (higher parental involvement and higher interparental affection) report more perseverance and connectedness (Xia, 2022). For youths in residential programs, family involvement and empowerment are related to success during and after treatment (Coll et al., 2022; Trout et al., 2013, 2020). Providing youths and families with family activities related to resilience could improve youth transition from residential care and long-term outcomes.

Faith

Faith items included “prayer,” going to “church” or “synagogue,” “sweat lodge,” and “youth group.” Youths in the study discussed individual practices around faith, along with religious involvement with their family, church, and community. Religion has been shown to have many benefits on youth development such as commitment to academics, healthy lifestyle, positive social relationships, coping with stress, and promoting family activities (Pinckney et al., 2020). African American and Latinx youths in our study ranked faith and religion as highly beneficial which is consistent with previous literature. Several studies demonstrated how prayer and cultural faith practices are related to resilience—particularly among African American and Latinx youths (Killgore et al., 2020). For instance, in a study of African American and Latinx inner-city youths, youths who were involved in church were less stressed, less likely to have psychological problems, and more likely to have a job compared to adolescents not involved in church (Cook, 2000). In a study of youths with elevated levels of ACEs, spirituality was a significant protective factor against depression (Freeny et al., 2021). Another study of low-income African American youths in Chicago found religious involvement was a protective factor against delinquency, drug use, and risky sexual behavior, and related to higher rates of school engagement (Kim et al., 2018). Studies across other cultures and religions (e.g., in Muslim youth in Iran and Australia) found religiosity was positively correlated with emotional and behavioral health including problem-solving, self-regulation, and family support (Rafi, 2020) and promoted resilience by providing a sense of belonging, social support, empowerment through service, and a sense of meaning and hope (Mitha & Adatia, 2016). American Indian youths in our study shared the importance of attending the sweat lodge located on the campus of the residential program. This aligned with guidelines for residential programs based on First Nations teaching that use sweat lodges to help youths heal (Chalmers and Dell, 2011).

We also found African American and Latinx youths ranked faith and religion high as both an individual and community factor, but White youths only ranked it high as an individual factor. This could suggest there are special considerations needed to maximize faith and religion as a protective factor. The impact religion has on moral outcomes in youths is mediated through relationships with peers, adults, and family members (King & Furrow, 2004). For instance, Ngyuen-Gillham et al. (2008) argue the collective resiliency and social capital of religious communities can be overlooked when faith is used as an individual intervention from a Western perspective. To maximize the individual and community benefits of faith and religion, Van Dyke and Elias (2007) suggest collaboration between community and religious settings to reach youths in natural environments that can encourage prosocial values such as empowerment, social change, forgiveness, and purpose. The gender identity or sexual orientation of youths should also be considered. For example, Longo et al. (2013) found religion can pose a potential risk factor for youths whose sexual orientation may conflict with their religious beliefs, resulting in feelings of shame, immorality, and or even manifesting in self-injurious behaviors. The authors recommend youths find ways to reduce the internal conflict by finding religious leaders who are affirming, belonging to the religious community without believing all of the religious teachings, or finding meaning and purpose in other ways. Considerations for the role faith plays in promoting positive outcomes for youths in residential programs warrant further exploration.

Self-Care and Community

Ideas related to self-care and community connectedness included “going for a car ride,” treating yourself to something you like such as getting a “haircut” or “nails done,” and going to cultural events such as “fairs,” “car shows,” and “festivals.” These were ranked high particularly among our African American and Latinx youths. Family ethnic socialization is the process of exposing children to culturally relevant events or places that represent one’s ethnic-background or ethnic pride (Martinez-Fuentes et al., 2021). In African American youths, self-care can be related to identity and linked to cultural pride (Wilcox et al., 2021). For example, youths in our study stated “getting hair done” and going to the salon or “barbershop” were related to resilience. Barbershops and beauty salons can create a family environment for Black youth, providing them with a place to share their views and get feedback, in addition to expressing themselves through their hairstyles (Dawson, 2020; National Museum of African American History and Culture, (n.d.)).

Participation in community events can also be a source of resilience through cultural connectedness (Hodgson et al., 2022). Youths in rural areas can gain community identity from participation in traditional activities such as rodeos and fairs (Larson & Dearmont, 2002). In our study, Latinx youths stated how going to community events and car shows were meaningful activities. For Indigenous youths, Elders in one study have suggested youth participate in traditional activities such as music making, dancing, and hearing stories about survival to gain a sense of community identity (Kahn et al., 2016). It is strongly recommended that residential programs use a culture-based model of resilience for First Nations and Aboriginal youths to help them reconnect with their culture, family, and the community (Chalmers & Dell, 2011; Hill et al., 2022).

Helping Others

Helping others included ideas such as “doing something nice for someone else,” “helping others in need,” and “volunteering time” which was ranked high by African American youths in our study. Youths shared ideas about the importance of helping those less fortunate through charitable giving and volunteer work, and some referred to this as an important value in their family. Volunteer work can improve communication and interpersonal skills and increase social capital, confidence, and self-esteem in youths (Webb et al., 2017). The value of helping others also transcends cultural differences. In Indigenous cultures, both within the US and Australia, being of value to others, generosity (Brokenleg, 2012), and civic connectedness are keys to social resilience (Gale & Bolzan, 2013). For youths in rural communities, helping others can involve participation in traditional activities such as harvests and branding times that connect them to their neighbors and community (Larson & Dearmont, 2002). Other studies have shown how volunteering can protect youths against academic failures, antisocial behavior, and substance use (Post, 2017). For youths requiring residential services, volunteering gets them involved in the community in a positive way, while teaching them skills such as respecting others, learning to be helpful to others, and building civic responsibility (Mueller, 2005).

Implications for Practice

Many of the ideas shared by youths during the focus groups converged with healthy activities related to resilience found in the residential literature, as well as research conducted with other youths of diverse cultures in the United States and around the world. Our study showed there was good alignment across different races and ethnicities in the themes identified, and differences in the unique activities that were shared based on the race, ethnicity, and cultures of different youths. The results will be used to further develop the HARRY so that it can be administered to youths as they enter residential programs. Conducting this screen at intake in conjunction with trauma screening will provide residential staff with insight into youths’ interests in different activities that may promote resilience to protect against trauma. This information in turn can be incorporated into the treatment planning for the youths and their families. For example, the specific resilience activities could be suggested for the youths to strengthen protective factors, to cope with difficult situations, and to provide recommendations for activities during time spent with their families during visits, and when they transition back home. These recommendations are consistent with strength-based approaches for trauma-informed residential programs (Association for Children’s Residential Centers, 2014).

Limitations and Future Directions

Our study included a diverse sample of youths from across the United States, and the results converged with the broader literature on resilience. The sample size was adequate for the focus groups based on typical saturation of ideas obtained with four focus groups (Hennink and Kaiser, 2022) with 20 to 30 participants total (Creswell, 2015). However, there were limitations. This study included youths who were placed in the same residential program for mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders and may not generalize to youths in other residential programs or mental health service settings. A larger sample size of youths in residential programs is needed for confirmatory factor analysis to further develop and refine the HARRY for clinical use. The sample also lacked adequate representation from American Indian, Asian American, and Middle Eastern American youths. The consideration of other culture-relevant characteristics, such as immigrant status, may also provide further insights. The family and community environment that youths came from prior to being placed in the residential programs was also not examined in this study. Exploring how neighborhood and community resilience (see Noelke et al., 2020), such as education, health/environment, and social/economic factors, are related to risks and resilience of youths placed in residential programs is suggested. Residential and mental health practitioners’ opinions about the developed instrument (i.e., HARRY) are also needed to see how useful the results from the screen are in informing strength-based treatment planning.

Conclusion

This study identified healthy activities related to resilience from a culturally diverse group of youths in a residential program. It shows the benefits of using a participatory action research approach that had benefits for the participants and was generalizable to aid in addressing a complex need in the community (Institute of Development Studies, 2024). In this clinical context, it involved learning from the clients through an empowering and respectful partnership (Yeager & Bauer-Wu, 2013) where youth provided solutions to a collective problem and were able to use the results of the research immediately. Additionally, the study incorporated cultural humility by learning from the youths about their resilience to create cultural awareness and identify potential imbalances based on race and ethnicity (Mosher et al., 2017). In our study, the youths shared similar themes related to resilience and specific activities that were influenced by their race and ethnicity. For us, this demonstrated that the underlying constructs of what youths used to overcome adversity may be universal, but how they did this was unique to their culture, family, and community. As a result, these youths helped develop an early version of a resilience screen that can be used with other culturally diverse youths placed in residential programs going forward.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Association for Children’s Residential Centers. (2014). Trauma-informed care in residential treatment. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 31, 97–104.

Bell, E. R. (2017). “This isn’t underground; This is highlands”: Mayan-language hip hop, cultural resilience, and youth education in Guatemala. Journal of Folklore Research, 54(3), 167–197. https://doi.org/10.2979/jfolkrese.54.3.02

Bettman, J. E., Lundahl, B. W., Wright, R., Jasperson, R. A., & McRoberts, C. H. (2011). Who are they? A descriptive study of adolescents in wilderness and residential programs. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 28(3), 192–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2011.596735

Boyer, S. N., Hallion, L. S., Hammell, C. L., & Button, S. (2009). Trauma as a predictiveindicator of clinical outcome in residential treatment. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 26, 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865710902872978

Braun-Lewensohn, O., Celestin-Westreich, S., Celestin, L.-P., Verleye, G., Verté, D., & Ponjaert-Kristoffersen, I. (2009). Coping styles as moderating the relationships between terrorist attacks and well-being outcomes. Journal of Adolescence, 32(3), 585–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.06.003

Briggs, E. C., Greeson, J. K., Layne, C. M., Fairbank, J. A., Knoverek, A. M., & Pynoos, R. S. (2012). Trauma exposure, psychosocial functioning, and treatment needs of youth in residential care: Preliminary findings from the NCTSN Core Data Set. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 5, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361521.2012.646413

Brokenleg, M. (2012). Transforming cultural trauma into resilience. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 21(3), 9–13.

Cargo, M., & Mercer, S. L. (2008). The value and challenges of participatory research: Its practice. Annual Review of Public Health, 29, 325–350. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.091307.083824

Castro, F. G., Garfinkle, J., Naranjo, D., Rollins, M., Brook, J. S., & Brook, D. W. (2007). Cultural traditions as “protective factors” among Latino children of illicit drug users. Substance Use & Misuse, 42, 621–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080701202247

Chalmers, D., & Dell, C. A. (2011). Equine-assisted therapy with First Nations youth in residential treatment for volatile substance misuse: Building an empirical knowledge base. Native Studies Review, 20(1), 59–87.

Cohen, J. (2007). Resilience and developmental psychology. Child Adolescent Clinics of North America, 16, 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2006.11.003

Coll, K. M., Stewart, R. A., Scholl, S., & Hauser, N. (2022). Interpersonal strengths and family involvement for adolescents transitioning from therapeutic residential care: An exploratory study. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 39, 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2021.1985684

Collishaw, S., Pickles, A., Messer, J., Rutter, M., Shearer, C., & Maughan, B. (2007). Resilience to adult psychopathology following childhood maltreatment: Evidence from a community sample. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.02.004

Conger, R. D., & Conger, K. J. (2002). Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 361–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00361.x

Cook, K. V. (2000). You have to have somebody watching your back, and if that’s God, then that’s mighty big: The church’s role in the resilience of inner-city youth. Adolescence, 35(140), 717–730.

Creswell, J. W. (2015). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. Sage Publications.

Crews, D. J., Lochbaum, M. R., & Landers, D. M. (2004). Aerobic physical activity effects on psychological well-being in low-income Hispanic children. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 98(1), 319–324.

Cui, G., & Zhang, L. (2022). The influence of physical exercise on college students’ negative emotions: The mediating and regulating role of psychological resilience. Journal of Sports Psychology, 31(2), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1037518

Dawson, K., Joscelyne, A., Meijer, C., Steel, Z., Silove, D., & Bryant, R. A. (2018). A controlled trial of trauma-focused therapy versus problem-solving in Islamic children affected by civil conflict and disaster in Aceh, Indonesia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52, 253–261. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867417714333

Dawson, M. (2020). Why the culture of black barbershops is so important. New York Post. Retrieved June 16, 2023 from https://nypost.com/2020/09/05/why-the-culture-of-black-barbershops-is-so-important/

Daykin, N., Viggiani, N., Moriarty, Y., & Pilkington, P. (2017). Music-making for health and wellbeing in youth justice settings” Mediated affordances and the impact of context and social relations. Sociology of Health and Illness, 39(6), 941–958. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12549

DBT Tools. (2023). TIP skill. Retrieved June 17, 2023, from https://dbt.tools/distress_tolerance/tip.php

DiClemente, C. M., Rice, C. M., Quimby, D., Richards, M. H., Grimes, C. T., Morency, M. M., White, C. M., Miller, K. M., & Pica, J. A. (2018). Resilience in urban African American adolescents: The protective enhancing effects of neighborhood, family, and school cohesion following violence exposure. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 38(9), 1286–1321.

Doan, S. N., Yu, S. H., Wright, B., Fung, J., Saleem, F., & Lau, A. S. (2022). Resilience and family socializatio processes in ethnic minority youth: Illuminating the achievement-health paradox. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 25(1), 75–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-022-00389-1

Dogan, C. (2015). Training at the gym, training for life: Creating better versions of self through exercise. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 11(3), 442–458. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v11i3.951

Ernestus, S. M., & Pelow, H. M. (2015). Patterns of risk and resilience in African American and Latino youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 43, 954–972. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21725

Father Flanagan’s Boys’ Home. (2015). Family Home Program: Program manual. Father Flanagan’s Boys’ Home.

Fayyad, J., Cordahi-Tabet, C., Yeretzian, J., Salamoun, M., Najm, C., & Karam, E. G. (2017). Resilience-promoting factors in war-exposed adolescents: An epidemiologic study. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 26, 191–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0871-0

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8

Freeny, J., Peskin, M., Schick, V., Cuccaro, P., Addy, R., Morgan, R., Lopez, K. K., & Johnson-Bake, K. (2021). Adverse childhood experiences, depression, resilience, & spirituality in African American adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 14, 209–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-020-00335-9

Gale, F., & Bolzan, N. (2013). Social resilience: Challenging new-colonial thinking and practices around risk. Journal of Youth Studies, 16(2), 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2012.704985

Green, R., Hatzikiriakidis, K., Tate, R., Bruce, L., Smale, M., Crawford-Parker, A., Carmody, S., & Skouteris, H. (2022). Implementing a healthy lifestyle program in residential out-of-home care: What matters, what works and what translates. Health and Social Care, 30, 2392–2403. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13773

Hagan, R., & Spinazzola, J. (2013). Real Life Heroes in residential treatment: Implementation of an integrated model of trauma and resiliency-focused treatment for children and adolescents with complex PTSD. Journal of Family Violence, 28, 705–715. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-013-9537-6

Heid, O., Khalid, M., Smith, H., Kim, K., Smith, S., Wekerle, C., Bomberry, T., Hill, L. D., General, D. A., Green, T. k. t. J., Harris, C., Jacobs, B., Jacobs, N., Kim, K., Horse, M. L., Martin-Hill, D., McQueen, K. C. D., Miller, T. F., Noronha, N., . . . The Six Nations Youth Mental Wellness, C. (2022). Indigenous youth and resilience in Canada and the USA: A scoping review. Adversity and Resilience Science, 3(2), 113-147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-022-00060-2

Hennink, M., & Kaiser, B. N. (2022). Samples sizes for saturation in qualitative research: A systematic review of empirical tests. Social Science and Medicine, 292, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114523

Hess, J. (2019). Moving beyond resilience: Musical counterstorytelling. Music Education Research, 21(5), 488–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/14613808.2019.1647153

Hill, B., Williams, M., Woolfenden, S., Martin, B., Palmer, K., & Nathan, S. (2022). Healing journeys: Experiences of young Aboriginal people in an urban Australian therapeutic community drug and alcohol program. Health Sociology Review, 31(2), 193–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2022.2091948

Hinton, D. E., & Lewis-Fernandez, R. (2011). The cross-cultural validity of posttraumatic stress disorder: Implications for DSM-5. Depression & Anxiety, 28, 783–801.

Hodgson, C. R., DeCoteau, R. N., Allison-Burbank, J. D., & Godfrey, T. M. (2022). An updated systematic review of risk and protective factors related to the resilience and well-being of indigenous youth in the United States and Canada. American Indian & Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal of the National Center, 29(3), 136–195. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.2903.2022.136

Huscroft-D’Angelo, Trout, A., J., Hennignsen, C., Synhorst, L., Lambert, M., Patwardhan, I., & Tyler, P. (2019). Legal professional perspectives on barriers and supports for youth and families during reunification from foster care. Child and Youth Services Review, 107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104525

IBM. (2017). Corp. Released. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

IBM. (2021). KMO and Bartlett’s test. Retrieved May 15, 2023, from https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/spssstatistics/26.0.0?topic=detection-kmo-bartletts-test

Institute of Development Studies. (2024). Participatory methods. People working together around the world to generate ideas and action for social change. Retrieved February 21, 2024 from https://www.participatorymethods.org/glossary/participatory-action-research

Kahn, C. B., Reinschmidt, K., Teufel-Shone, N., Oré, C. E., Henson, M., & Attakai. (2016). American Indian elder’s resilience: Sources of strength building a healthy future for youth. Indian & Alaska Native Mental Health Research: The Journal of the National Center, 23(3), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.5820/aian.2303.2016.117

Kam, J. A., Torres, D. P., & Fazio, K. S. (2018). Identifying individual- and family-level coping strategies as sources of resilience and thriving for undocumented youth of Mexican origin. Journal of Applied Communication Resarch, 46(5), 641–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2018.1528373

Killgore, W. D. S., Taylor, E. C., Cloonan, S. A., & Dailey, N. S. (2020). Psychological resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown. Psychiatry Research, 291, 113216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113216

Kim, D. H., Harty, J., Takahashi, L., & Voisin, D. R. (2018). The protective effects of religious beliefs on behavioral health factors among low-income African American adolescents in Chicago. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27, 355–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0891-5

Kim-Cohen, J. (2007). Resilience and developmental psychopathology. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 16(2), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2006.11.003

King, P. E., & Furrow, J. L. (2004). Religion as a resource for positive youth development: Religion, social capital, and moral outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 40(5), 703–713. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.703

LaFromboise, T. D., Hoyt, D. R., Oliver, L., & Whitbeck, L. B. (2006). Family, community, and school influences on resilience among American Indian adolescents in the upper Midwest. Journal of Community Psychology, 34(2), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20090

Larson, N. C., & Dearmont, M. (2002). Strengths of farming communities in fostering resilience in chidlren. Child Welfare, 81(5), 821–835.

Lei, M., & Beach, S. R. H. (2020). Can we uncouple neighborhood disadvantage and delinquent behaviors? An experimental test of family resilience guided by social disorganization theory of delinquent behaviors. Family Process, 59(4), 1801–1817. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12527

Li, M., Eschenauer, R., & Persaud, V. (2018). Between avoidance and problem solving: Resilience, self-efficacy, and social support seeking. Journal of Counseling & Development, 96, 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12187

Linehan, M. (2020). Dialectical behavior therapy in clinical practice. Guildford Publications.

Longo, J., Wals, E., & Wisneski, H. (2013). Religion and religiosity: Protective or harmful factors for sexuality minority youth. Mental Health, Religion, & Culture, 16(3), 273–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2012.659240

MacDonald, K., Thomas, M. L., Sciolla, A. F., Schneider, B., Pappas, K., Bleijenber, G., ... & Wingfeld, K. (2016). Minimization of childhood maltreatment is common and consequential: Results from a large, multinational sample using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. PLoS ONE, 11, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0146058

Martinez-Fuentes, S., Jager, J., & Umana-Taylor, A. J. (2021). The mediation proccess between Latino youths’ family ethnic socialization, ethnic-racial identity, and academic engagement: Moderation by ethnic-racial discrimination. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 27(2), 296–306. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000349

Masten, A. S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.56.3.227

McKinney, C. M., Harris, T. R., & Caetano, R. (2009). Reliability of self-reported childhood physical abuse by adults and factors predictive of inconsistent reporting. Violence and Victims, 24, 653–668. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.24.5.653

Minkler, M., Glover Blackwell, A., Thompson, M., & Tamir, H. (2003). Community-based participatory research: Implications for public health funding. Public Health Advocacy Forum, 93(8), 1210–1213. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.8.1210

Mitha, K., & Adatia, S. (2016). The faith community and mental health resilience amongst Australian Ismali Muslim youth. Mental Health, Religion, & Culture, 19(2), 192–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2016.1144732

Mosher, D. K., Hook, J. N., Captari, L. E., Davis, D. E., & DeBlaere, C. (2017). Cultural humility: A therapeutic framework for engaging diverse clients. Practice Innovation, 2(4), 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/pri0000055

Mueller, A. (2005). Antidote to learned helplessness: Empowering youth through service. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 14(1), 16–19.

Mueser, K. T., & Taub, J. (2008). Trauma and PTSD among adolescents with severe emotional disorders involved in multiple service systems. Psychiatric Services, 59, 627–634. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2008.59.6.627

National Museum of African American History and Culture. (n.d.) The community roles of the barbershop and beauty salon. Retrieved June 16, 2023 from https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/community-roles-barbershop-and-beauty-salon

Nelson, J. S., Jayanthi, M., Brittian, C. S., Epstein, M. H., & Bursuck, W. D. (2002). Using the nominal group technique for homework communication decisions. Remedial and Special Education, 23, 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/07419325020230060801

Nguyen-Gillham, V., Giacaman, R., Naser, G., & Boyce, W. (2008). Normalising the abnormal: Palestinian youth and the contradictions of resilience in protracted conflict. Health and Social Care in the Community, 16(3), 291–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2008.00767.x

Noelke, C., McArdle, N., Baek, M., Huntington, N., Huber, R., Hardy, E., & Acevedo-Garcia, D. (2020). Child opportunity index 2.0 technical documentation. Retrieved from diversitydatakids.org/researchlibrary/research-brief/how-we-built-it

Payne, Y. A., & Gibson, L. R. (2008). Hip hop music and culture: A site of resiliency for the streets of young black America. In H. A. Nelville, B. M. Tynes, & S. O. Utsey (Eds.), The handbook of African-Americanpsychology (pp. 127–141). Sage.

Pejičić, M., Ristić, M., & Andelković, V. (2017). The mediating effect of cognitive emotion regulation strategies in the relationship between perceived social support and resilience in postwar youth. Journal of Community Psychology, 46, 457–472. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21951.10.1002/JCOP.21951

Perrino, T., Brincks, A., Lee, T. K., Quintana, K., & Prado, G. (2019). Screen-based sedentary behaviors and internalizing symptoms across time among US Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 72, 91–100.

Pinckney, H. P., Clanton, T., Garst, B., & Powell, G. (2020). Faith-based organizations: Oft overlooked youth development zones. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 38(1), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.18666/JPRA-2019-8232

Post, S. G. (2017). Prescribing volunteerism for health, happiness, resilience, and longevity. American Journal of Health Promotion, 31(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890117117691705

Rafi, M. (2020). The influence of religiosity on the emotional-behavioral health of adolescents. Journal of Religion and Health, 59, 1870–1888. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-00747-w

Ranjbar, N., Erb, M., Mohammad, O., & Moreno, F. A. (2020). Trauma-informed care and cultural humility in the mental health care of people from minoritized communities. Focus, 18(1), 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20190027

Reed, J. A., Maslow, A. L., Long, S., & Hughey, M. (2013). Examining the impact of 45 minutes of daily physical education on cognitive ability, fitness performance, and body composition of African American youth. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 10(2), 185–197.

Richards, J., Jiang, X., Kelly, P., Chau, J., Bauman, A., & Ding, D. (2015). Don’t worry, be happy: Cross-sectional associations between physical activity and happiness in 15 European countries. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1391-4

Rutter, M. (2007). Resilience, competence, and coping. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(3), 205–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.02.001

Seifert, H. T. P., Farmer, E. M. Z., Wagner, H. R., Maultsby, L. T., & Burns, B. J. (2015). Patterns of maltreatment and diagnosis across levels of care in group homes. Child Abuse & Neglect, 42, 72–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.12.008

Smith, A. C. G., Crooks, C. V., & Baker, L. (2021). “You have to be resilient”: A qualitative study exploring advice newcomer youth have for other newcomer youth. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-021-00807-3

Sulimani-Aidan, Y. & Schwartz-Tayri, T. (2021). The role of natural mentoring and sense of belonging in enhancing resilience among youth in care. Children and Youth Services Review, 120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105773

Summerfield, D. (2000). Childhood, war, refugeedom and “Trauma”: Three core questions for mental health professionals. Transcultural Psychiatry, 37(3), 417–433. https://doi.org/10.1177/136346150003700308

Thompson, R. W., & Daly, D. L. (2015). The Family Home Program: An adaptation of the Teaching Family Model at Boys Town. In J. K. Whittaker, J. F. Del Valle, & L. Holmes (Eds.), Therapeutic Residential Care with Children and Youth: Developing Evidence-Based International Practice (pp. 113–123). Kingsley Publishers.

Trask-Tate, A., Cunningham, M., & Lang-DeGrange, L. (2010). The importance of family: The impact of social support on symptoms of psychological distress in African American girls. Research in Human Development, 7(3), 164–182.

Travis, R. (2013). Rap music and the empowerment of today’s youth: Evidence in everyday music listening, music therapy, and commercial rap music. Child Adolescent Social Work, 30, 139–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-012-0285-x

Travis, R., & Bowman, S. (2012). Ethnic identity, self-esteem, and variability in perceptions of rap music’s empowering and risky influences. Journal of Youth Studies, 15(4), 455–478. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2012.663898

Trout, A. L., & Epstein, M. H. (2010). Developing aftercare, Phase I: Consumer feedback. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(3), 445–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.10.024

Trout, A. L., Lambert, M., Epstein, M., Tyler, P., Stewart, M., Thompson, R. W., & Daly, D. (2013). Comparison of On the Way Home Aftercare supports to usual care following discharge from a residential setting: An exploratory pilot randomized controlled trial. Child Welfare, 92(3), 27–45.

Trout, A. L., Lambert, M. C., Thompson, R., Duppong Hurley, K., & Tyler, P. M. (2020). On the way home: Promoting caregiver empowerment, self-efficacy, and adolescent stability during family reunification following placements in residential care. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 37(4), 269–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2019.1681047

Tuffrey-Wijne, I., Bernal, J., Butler, G., Hollins, S., & Curfs, L. (2007). Using nominal group technique to investigate the views of people with intellectual disabilities on end-of- life care provision. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 58, 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04227.x

Tyler, P. M., Trout, A. L., Epstein, M. H., & Thompson, R. W. (2014). Provider perspectives on aftercare services for youth in residential care. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 31, 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2014.943571

Tyler, P. M., Trout, A. L., Huscroft-D’Angelo, J., Synhorst, L. L., & Lambert, M. (2018). Promoting stability for youth returning from residential care: Attorney perspectives. Juvenile and Family Court Journal, 69, 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfcj.12113

Tyler, P. M., Mason, W. A., Chmelka, M. B., Patwardan, I., Dobbertin, M., Pope, K., Shah, N., Rahim, H. A., Johnson, K., & Blair, R. J. (2019). Psychometrics of a brief trauma symptom screen for youth in residential care. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(5), 753–763. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22442

Tyler, P. M., Aitken, A. A., Ringle, J. L., Stephenson, J. L., & Mason, Q. A. (2021). Evaluating social skills training for youth with trauma symptoms in residential programs. Psychological Trauma: Theory Research Practice and Policy, 13(1), 104–113. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000589

Tyler, P. M., Hillman, D. S., & Ringle, J. L. (2022). Peer relations training moderates trauma symptoms and suicide ideation for youth in a residential program. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 31, 447–458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02193-x

Ungar, M. (2013). Resilience, trauma, context, and culture. 14(3), https://doi.org.leo.lib.unomaha.edu/https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838013487805

United States Department of Health and Human Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration for Substance Abuse Treatment. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (2014). Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services (SMA Publication No. 14–4816).

Van Dyke, C. J., & Elias, M. J. (2007). How forgiveness, purpose, religiosity are related to the mental health and wellbeing of youth: A review of the literature. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 10(4), 395–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674670600841793

VERBI Software. (2021). MAXQDA 2022 [computer software]. VERBI Software. Available from maxqda.com.

Wagnild, G. M. (2009). A review of the resilience scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 17, 105–113. https://doi.org/10.1891/1061-3749.17.2.105

Webb, L., Cos, N., Cumbers, H., Martikke, S., Gedzielewski, E., & Duale, M. (2017). Personal resilience and identity capital among young people leaving care: Enhancing identify formation and life choices through involvement in volunteering and social action. Journal of Youth Studies, 20(7), 889–903. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2016.1273519

Wilcox, L., Larson, K., & Barlett, R. (2021). The role of resilience in ethnic minority adolescent navigation of ecological adversity. Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, 14, 507–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-020-00337-7

Williams, J. M., & Bryan, J. (2012). Overcoming adversity: High-achieving African American youth’s perspective on educational resilience. Journal of Counseling & Development, 91, 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2013.00097.x

Williams, N. R., Lindsey, E. W., Kurtz, P. D., & Jarvis, S. (2001). From trauma to resiliency: Lessons from former runaway and homeless youth. Journal of Youth Studies, 4, 233–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260123589

Willoughby, T., & Hamza, C. A. (2011). A longitudinal examination of the bidirectional associations among perceived parenting behaviors, adolescent disclosure, and problem behavior across the high school years. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 40, 463–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9567-9

Wolf, M. M., Kirigin, K. A., Fixsen, D. L., Blasé, K. A., & Braukmann, C. J. (1995). The Teaching-Family Model: A case study in data-based program development and refinement (and dragon wrestling). Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 15, 11–68. https://doi.org/10.1300/J075v15n01_04

Woods-Jaeger, B., Sielik, E., Adams, A., Piper, K., O’Coonor, P., & Berkley-Patton, J. (2020). Builidng a contexually-relevant understanding of resilience among African American exposed to community violence. Behavioral Medicine, 46(3–4), 330–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2020.1725865

Xia, M. (2022). Different families, diverse strengths: Long-term implications of early childhood family processes on adolescent positive functioning. Developmental Psychology, 58(10), 1863–1874. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001401

Yeager, K. A., & Bauer-Wu, S. (2013). Cultural humility: Essential foundation for clinical researchers. Applied Nursing Research, 26(4), 251–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2013.06.008

Zheng, Y., Cai, D., Zhao, J., Yang, C., Xia, C., & Xu, Z. (2021). Bidirectional relationships between emotional intelligence and perceptions of resilience in young adolescents: A twenty-month longitudinal study. Child and Youth Care Forum, 50, 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-020-09578-x

Zimmerman, M. A., Stoddard, S. A., Eisman, A. B., Caldwell, C. H., Aiyer, S. M., & Miller, A. (2013). Adolescent resilience: Promotive factors that inform prevention. Child Developmental Perspectives, 7(4), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12042

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible by the Boys Town Nebraska Biomedical Research Development Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Patrick M. Tyler, Ph.D.; Josh Day, M. Sc.; Mary B. Chmelka, B. S.; and Jada Loro, M. A., are employed by the Child and Family Translational Research Center, Boys Town National Research Hospital, Boys Town, Nebraska, USA. Chanelle T. Gordon, Ph.D., was affiliated with the Boys Town National Research Hospital at the time of this study and is now employed by the Omaha VA Medical Center. There are no conflicts of interest to report for any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tyler, P.M., Day, J., Chmelka, M.B. et al. Developing a Culturally Informed Resilience Screen for Youths in Residential Programs. ADV RES SCI (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-024-00142-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-024-00142-3