Abstract

Research in Indigenous communities continues to lead innovations in the adversity and resilience sciences. These innovations highlight the strengths of Indigenous communities and are an act of resistance against prevailing stereotypes that Indigenous communities are vulnerable and wholly restrained by health deficits. The aim of this Supplemental Issue on Substance Misuse and Disorder and American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian Children’s Development: Understanding Root Causes and Lifting up Solutions Grounded in Indigenous Community Strengths is to highlight the promising new approaches and perspectives implemented by a group of engaged researchers and their community partners, as they seek to move resilience science research forward. Case studies presented in this issue are from projects led by teams connected to the Native Children’s Research Exchange (NCRE) conference, all of whom conduct health promotion and disease prevention research among American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians. Sparked by several major exogenous shocks to the current landscape of the American milieu, namely, the COVID-19 pandemic, the murder of George Floyd (increased visibility of overt racism in the USA), and climate change, this article presents a model for conducting research with Indigenous Communities that acknowledges these forces while highlighting community strengths.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In 2020, a confluence of national and global events highlighted longstanding forces that have exacerbated substance misuse and disorder in Indigenous communities. The COVID-19 pandemic disproportionately impacted Indigenous communities which experienced the highest rates of infection, severe disease, and death compared to other population groups (Yellow Horse et al., 2021). Surges in opioid use and overdose deaths around the country during the pandemic’s peak (and beyond) were also particularly concentrated in Indigenous communities (Case & Deaton, 2020). Attempts to understand the causes of these disparities in both susceptibility to COVID-19 infection and substance misuse highlighted a host of inequities that have long put Indigenous communities in the USA at greater risk for poor public health outcomes (Sarche & Spicer, 2008; Sequist, 2017). Three specific sources of inequity were illuminated during this time. First, the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer catalyzed a movement to acknowledge and address systemic racism and its profound impacts on minoritized communities (Dreyer et al., 2020). Second, resulting attention to systemic racism in Indigenous communities called attention to its roots in structures created and maintained through centuries of colonial oppression (Ivanich et al., 2022a, 2022b). And third, climate change has increased threats to many Indigenous communities. Climate change has affected entire Alaska Native villages, which have been consumed by rising rivers, and has threatened subsistence lifestyles across all Indigenous communities, directly impacting ceremonial and sacred lands, harvesting of sacred medicines, and land-based traditions (Flavelle et al., 2021). These intersecting forces resulted in multilayered trauma for generations of Indigenous families, leading to profound and complex impacts on their health and well-being, including, but not limited to, substance use (Krieger, 2020; Whitbeck et al., 2014).

These significant societal inequalities have had direct impacts on individual-level outcomes for American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian (Indigenous) communities. Disproportionate rates of substance use disorder have disrupted Indigenous communities for many years, with repercussions on the health and welfare of individuals, families, communities, and children in particular (Beals et al., 2005a; Beals et al., 2005b; Grant et al., 2015; Mokuau et al., 2016; Whitbeck et al., 2014). The disproportionate rates of substance use disorder we see today stem directly from the history of racialized trauma and systemic assaults on Indigenous families, creating risk for substance misuse and disorder and perpetuating substance misuse-driven family dysfunction. Indigenous children today thus bear an unjust exposure to substance use disorder and its effects on their families and communities. The harmful impacts of substance use on children can occur through direct and indirect pathways. For instance, prenatal exposure to harmful substances has direct pathways to harm development, while equally problematic indirect pathways, such as the effect of substance use on parenting practices, mental health, and maltreatment, compromise children’s socio-emotional, cognitive, and physical development from early childhood through adolescence and beyond (Carta et al., 2001; Glantz & Chambers, 2006; Mancuso, 2018). Indigenous youth have higher rates of early initiation of substance use, which is related to trauma exposure (Whitbeck & Armenta, 2015; Whitesell et al., 2009). Trauma exposure and early use, in turn, predict later substance use disorder (Eiden et al., 2016; Fitzgerald & Puttler, 2018; Whitbeck et al., 2014; Whitesell et al., 2014), which further perpetuates the cycles of intergenerational despair.

An Organizing Framework to Inform Research on the Impacts of Substance Use on Indigenous Children

In the midst of the global pandemic and aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, the Native Children’s Research Exchange (NCRE), an Indigenous serving mentorship program as well the host of an annual conference, focused on Indigenous child development (Ivanich et al., 2022a) and brought together leading researchers to reflect on the state of research on the intersection of substance misuse and Indigenous children’s development. The goal was to highlight significant research questions and to provide a framework for moving the field of substance use and Indigenous child development forward. This work, jointly sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R13DA051122, Whitesell & Sarche, PIs) and the Tribal Early Childhood Research Center (90PH0030, Sarche, PI), occurred throughout 2021, while the country (and the world) navigated the ongoing pandemic, an epidemic of opioid overdoses, and increased threats due to climate change. The author’s goal for the framework described in this paper was to understand and illustrate the structural changes needed to achieve health equity in this context. It became clear that to move toward solutions, the framework the group set out to develop must acknowledge the impacts of all three forces (structural racism, colonial oppression, and climate change) on substance misuse and disorder in Indigenous families, children, and communities while highlighting opportunities for prevention and healing. This paper describes the process used to create this framework, shares the framework, introduces the papers in this special issue about this framework, and sets the stage for future contributions that address substance use disorder, Indigenous children’s development, or other aspects of the framework in service to Indigenous children’s health and wellbeing.

Culturally Informed Approach

We began this work in consultation with the NCRE Conference Planning Committee (CPC), with early conversations about what a conceptual framework might look like. Those broader group conversations then moved to identifying a subcommittee of six individuals (AB, HF, SO, JS, MS, NRW, the final six authors of this paper). All researchers have years of experience studying substance misuse and disorder, Native children’s development, or both. All have been working for years in community-based participatory research with Indigenous communities. However, only one of these senior researchers is themselves Indigenous (MS); all but one of the others (SO) are white. As we began to talk with this group about the state of the science on substance use and its impacts on Indigenous children, we recognized the need to bring the voices of Indigenous researchers into the conversation. We invited six additional partners (JI, JSU, TKKM, MM, KS, and EW—the first six authors on this paper) to join this work, all of whom have been participants in the NCRE Scholars program (R25DA050645, Whitesell & Sarche, PIs), which provides mentorship to early career Indigenous researchers (Ivanich et al., 2022b). Though early in their careers, each of these individuals has already distinguished themselves by making significant contributions to Indigenous theory, research, and/or methodology. We named this expanded group the Conceptual Framework Development Team (CFDT) and began collaborating to create the framework. With the formation of the CFDT, one of these scholars (JI) took on leadership for facilitating the group and is the first author of this paper.

As described below, while the CFDT did the most intensive work to create this framework, we also engaged a larger group of researchers to review and provide input on the framework. This larger group included other members of the NCRE CPC (N = 15, 4 of them Indigenous) along with a larger group of NCRE Scholars (N = 10, 9 of them Indigenous).

Steps in the Process

Since the work to develop this conceptual model took place in 2021, travel was still widely restricted, including by university policies for many partners. Therefore, we worked together through a series of virtual meetings.

Foundational Phase: NCRE Conference Planning Committee

We began meeting with the NCRE CPC in May of 2021. At that first meeting, we discussed elements that should be included in a conceptual framework. With the guidance provided, the last author sketched out an initial framework visual that went through four iterations of revisions with the CPC and was informed by discussion at two additional CPC meetings and extensive email communication. At that point, the decision was made to form a subcommittee to work more intensely on refining the framework, and the smaller CFDT workgroup began meeting separately. Progress made during this foundational phase included the identification of the Indigenous Connectedness Framework (Ullrich, 2019) as particularly relevant to the conceptual framework we were building.

Developmental Phase: Conceptual Framework Development Team

As noted above, in forming the CFDT, we recognized the need to ensure Indigenous perspectives in creating a framework for understanding Indigenous experiences, so we invited six NCRE scholars to join this group, including the author of the Indigenous Connectedness Framework (JSU). The CFDT began meeting in September 2021 and continued through early December of that year. As with the foundational phase, work in the developmental phase involved both virtual meetings and email feedback to inform framework revisions. Five iterations of the framework were created during this phase to create a draft conceptual framework that could be shared with a larger group for refinement.

Broader Input Phase: NCRE Working Meeting

On December 9, 2021, we held a virtual meeting with a larger contingent of researchers affiliated with NCRE, including (1) 18 academic researchers with expertise in substance use and misuse and/or child development in Indigenous communities, (2) 12 NCRE scholars (graduate students, post docs, and early career academic or community-based researchers), (3) five community research partners, and (4) five research partners from federal funding agencies. We shared the draft framework prepared by the CFDT ahead of this meeting. At the meeting, we provided an overview of the framework before working in smaller breakout groups to discuss the framework. Breakout groups were organized to obtain diverse feedback and elevate the voices of groups within the larger meeting (i.e., two groups of academic researchers, one group of community researchers, one group of early career researchers in the NCRE Scholars program, and one group of research partners from federal funding agencies). After allowing 45 min for these intensive discussions, we returned to the larger meeting and spent another 45 min where each group shared critical reflections—including concrete suggestions for improving the framework. The meeting concluded with a full-group discussion and identification of action items for the next iteration of the framework.

Refinement Phase: CFDT

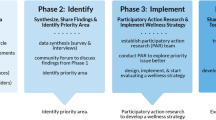

With the input from the larger working group, we reconvened the CFDT in December 2021 and worked with that group through February 2022 to make additional refinements. This work included two virtual meetings and extensive email exchanges among group members. The final product, shown in Fig. 1, is an application of the Indigenous Connectedness Framework (ICF) to Address Substance Misuse in Indigenous Children’s Development and understand causes, consequences, and solutions.

Key Principles Incorporated into the Framework

In explaining the Framework, it is essential to share the key principles that emerged in discussions with the CPC, CFDT, and NCRE Working Group across all phases of framework development. These principles are translated as key elements in the final framework.

Disconnecting Forces

First, the idea of disconnecting forces was seen as an important way to frame the forces that disrupt Indigenous communities and children’s development. The three key disconnecting forces highlighted in the framework are colonial oppression, systemic racism, and climate change. There are undoubtedly other disconnecting forces that could be named. However, these three have become particularly salient in recent years, highlighted by inequities brought to light by the COVID-19 pandemic and parallel societal events. The pandemic did not create these forces; instead, it exposed them to a broader audience, laying bare forces many people in the USA have not seen or acknowledged before. Second, the direct impact of these disconnecting forces is seen as multilayered historical, generational, and cultural trauma. The history of colonial oppression has disrupted communities and cultures for generations, and the impacts are felt across generations, including to this day. Systematic efforts to strip Indigenous communities of their cultures, languages, community integrity, and lands are profound and ongoing. Third, the impact of disconnecting forces on multilayered trauma drives up substance use and misuse, eventuating in disparate rates of substance addiction, overdose, and death within Indigenous communities—that, in turn, becomes a further disconnecting and disruptive force impacting children and families.

Potential for Healing through Reconnecting

Disconnecting forces and their chains of influence leave Indigenous communities facing significant challenges in maintaining health and well-being among children and families. However, significant countervailing protective forces push back against these disconnecting forces, supporting the potential for healing through connection/reconnection. Our framework relies directly on the Indigenous Connectedness Framework (ICF) created by Jessica Saniġaq Ullrich along with Alaska Native community knowledge keepers (Ullrich, 2019). The ICF emphasizes the critical importance of spiritual and cultural connectedness in fostering relational well-being. In our application of ICF, reciprocal external relationships with others (e.g., with family, community, environment, and ancestors) are connecting forces that support a healthy internal relationship with self (e.g., sense of belonging, self-worth, trust). Together, these external and internal relationships support substance misuse and disorder healing, resilience, and prevention.

Value of the Framework for Guiding Research Related to Solutions for Substance Misuse and Disorder

NCRE brought this group of researchers together to take stock of the research on the relationship between substance misuse and disorder and Indigenous children’s development. The Framework was designed to provide guidance for research moving forward to more effectively address the root causes of substance misuse and disorder and to support solutions that address persistent inequities. The framework offers a way forward different from what has been tried and mainly found inadequate. Our framework suggests that solutions residing within Indigenous cultures and communities themselves are the most promising levers for change. Rather than continuing to try solutions imported from outside (which have the potential to be colonizing in themselves (Oppong, 2023)), we would do well to support the decolonization of these efforts, turning to Indigenous theories and methods. With this eye toward the future, we issued a call for papers for this special issue, asking researchers to submit work connected in some way to this Framework.

Papers in this Special Issue

The papers in this special issue connect to different elements of the framework shown in Fig. 1. Some cut across multiple elements, while others shine light more narrowly on one element. Here, we provide brief introductions and situate each paper within the framework. We encourage readers to delve deeply into each paper for their insights and examples on the disconnecting forces that drive substance misuse and disorder and the connecting forces that support healing.

The first paper we highlight clearly illustrates one type of disconnecting force: the systematic disruption of culture and connection through family separation. Waubanascum (this issue) examined colonization’s legacy and current impacts through the child welfare system. This study used the Conversational Method in Indigenous Research (Kovach, 2010) to engage 10 Indigenous individuals who served as relative caregivers in the child welfare system in Minnesota and Wisconsin. Findings point to important ways in which the child welfare system continues to extend policies to assimilate Indigenous people and perpetuate colonial violence, fostering ongoing traumatization of Indigenous children and families. This paper also explores how decolonizing child welfare by honoring kinship practices grounded in Indigenous knowledge (connecting forces) will support healthy, thriving (as defined by Indigenous communities) children, families (as defined by Indigenous communities), and communities.

The second paper reinforces the power of disconnecting forces. In a sexual assault prevention study, Armstrong et al. (this issue) surveyed 401 Indigenous college students in Oklahoma and North Dakota and interviewed a subsample of 14 survey participants. In the quantitative data, 72% of the sample screened positive for current PTSD symptoms, reflecting high levels of exposure to trauma. Qualitative data highlighted how systemic inequities place Indigenous peoples at higher risk for sexual violence and that substance use is often a means to cope with colonization, historical trauma, and contemporary trauma, including sexual trauma; a second theme was that some Indigenous communities are deeply affected by systemic inequities that act as barriers to care. These findings highlight how disconnecting forces put young adults at risk for substance use and, critically, that cultural and community engagement can be protective of connecting forces for healing.

Themes evident in both Waubanascum (this issue) and Armstrong et al. (this issue) reverberate in the third paper, Geary et al. (this issue). This study utilized an environmental scan to examine efforts in tribal communities to prevent prenatal alcohol and other drug exposure. Analyses concluded that the root causes of substance use in most tribal communities are linked to historical oppression and trauma and perpetuated by structural inequities in services and supports. This study also identified promising practices for prevention to integrate cultural practices and traditions into prevention approaches, highlighting, again, the potential power of connecting forces.

In the fourth paper, Tuitt et al. (2023) directly address how research itself is a disconnecting force: “Well-intentioned studies seeking to guide health promotion interventions, programs, and policies for [Native American] young people have been constrained by pervasive settler colonialism ingrained in the fabric of their research methodologies.” These authors provide a conceptual framework for understanding the role settler colonialism plays in research and that identifies opportunities to “unsettle” structures and systems that maintain inequitable and unproductive approaches.

Komro et al. (this issue; fifth paper) provide an example of utilizing research methods aligned with Indigenous communities to help find solutions to substance use and misuse among youth. This study highlights the power of a partnership that leverages the expertise of behavioral health specialists within the Cherokee Nation and university-based researchers focused on preventing substance misuse among youth. Partnerships such as this—research with Indigenous communities rather than about them—are essential to unsettling the colonialist research practices articulated by Tuitt et al. (2023). Komro et al. (this issue) examine the psychometric properties of an array of standard measures utilized in the larger study (drawn from the PhenX Toolkit and the Monitoring the Future study), testing them for reliability and validity with samples of AI and White youth living in the Cherokee Nation; such work is fundamental to getting accurate measurement for Indigenous youth and communities, so research findings can be trusted, meaningful, and impactful for addressing substance use and misuse among youth.

While Komro et al. (this issue) provide an example of research with an Indigenous community, the sixth paper, Willer et al. (this issue), is an example of research by an Indigenous community. This paper describes the work of the Cook Inlet Tribal Council (CITC) in Alaska to identify key outcomes for their work with families across multiple services (including education and youth services, family wellness, and addiction recovery) and to develop a measure of these outcomes. Two of the five key factors they identified—Healthy Relationships and Cultural and Spiritual Wellness—directly echo the connecting forces in the Fig. 1 framework. The processes shared in this paper guide other community organizations seeking to explore the outcomes that matter most to them.

The seventh paper, Reed et al. (this issue), is an example of engaging the community at a very different level. Rather than engaging a specific cultural and geographic community, the study described here created a virtual Indigenist community of urban young women. It implemented an online alcohol-exposed pregnancy prevention program. This project is an example of connecting forces, bringing young women across the country into a relationship with one another, and disseminating and testing an intervention through this network to prevent substance exposure in the prenatal period.

The final paper in this issue, Martin et al. (this issue), provides the strongest example of the power of connecting forces to promote healing. This paper does not focus directly on substance use and misuse outcomes but instead on how connections experienced by Indigenous and allied researchers better prepare them to do their work via an Indigenous Writing Retreat (IWR) and, thus, support solutions grounded in Indigenous wisdom. While the process for supporting researchers described in this paper is conceptualized from a Native Hawaiian perspective, we believe that it has broader applicability to future IWRs for researchers and also resonates with the recommendations in Tuitt et al. (2023) toward unsettling colonialist research structures and systems. It points to the value of supporting Indigenous researchers to carry their Indigeneity with them as they engage deeply in research rather than asking them to step away from who they are to adopt colonialist research paradigms and practices.

Conclusions

The year 2020 is among those that have been deeply transformative. We endured the COVID-19 pandemic, witnessed an awakening of awareness of systemic racism and the enduring impact of colonialism, and increasingly experienced the impacts of climate change. These experiences have highlighted the need to rethink how we interact with the world. For NCRE, they provided an opportunity to step back and critically evaluate the limited progress we and other researchers have made in stemming the impacts of substance misuse on the lives of Indigenous children. Together, we have created a framework that can serve as a guide to point the way forward for researchers and communities across the country, toward supporting solutions that arise from the strengths of Indigenous communities, building on connectedness within communities to overcome the disconnecting forces that have long put children and families at risk. The articles in this special issue—particularly the large number that highlights approaches grounded in culture and community—show the promise of activating solutions from within Indigenous communities and ways of life.

Change history

08 February 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-024-00128-1

References

Beals, J., Manson, S. M., Whitesell, N. R., Mitchell, C. M., Novins, D. K., Simpson, S., & Spicer, P. (2005a). Prevalence of major depressive episode in two American Indian reservation populations: Unexpected findings with a structured interview. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(9), 1713–1722. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1713

Beals, J., Novins, D. K., Whitesell, N. R., Spicer, P., Mitchell, C. M., & Manson, S. M. (2005b). Prevalence of mental disorders and utilization of mental health services in two American Indian reservation populations: Mental health disparities in a national context. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(9), 1723–1732. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1723

Carta, J. J., Atwater, J. B., Greenwood, C. R., McConnell, S. R., McEvoy, M. A., & Williams, R. (2001). Effects of cumulative prenatal substance exposure and environmental risks on children’s developmental trajectories. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30(3), 327–337.

Case, A., & Deaton, A. (2020). Deaths of despair and the future of capitalism. Princeton University Press.

Dreyer, B. P., Trent, M., Anderson, A. T., Askew, G. L., Boyd, R., Coker, T. R., Coyne-Beasley, T., Fuentes-Afflick, E., Johnson, T., Mendoza, F., Montoya-Williams, D., Oyeku, S. O., Poitevien, P., Spinks-Franklin, A. A. I., Thomas, O. W., Walker-Harding, L., Willis, E., Wright, J. L., Berman, S., … Stein, F. (2020). The Death of George Floyd: Bending the Arc of History Toward Justice for Generations of Children. Pediatrics, 146(3), e2020009639. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-009639

Eiden, R. D., Lessard, J., Colder, C. R., Livingston, J., Casey, M., & Leonard, K. E. (2016). Developmental cascade model for adolescent substance use from infancy to late adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 52(10), 1619.

Fitzgerald, H. E., & Puttler, L. I. (Eds.). (2018). Alcohol use disorders: A developmental science approach to etiology. Oxford University Press.

Flavelle, C., & Goodluck, K. (2021). Dispossessed, again: Climate change hits Native Americans especially hard. New York Times, 27,

Glantz, M. D., & Chambers, J. C. (2006). Prenatal drug exposure effects on subsequent vulnerability to drug abuse. Development and Psychopathology, 18(3), 893–922.

Grant, B. F., Goldstein, R. B., Saha, T. D., Chou, S. P., Jung, J., Zhang, H., Pickering, R. P., Ruan, W. J., Smith, S. M., & Huang, B. (2015). Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(8), 757–766.

Ivanich, J. D., Clifford, C., & Sarche, M. (2022a). Native American and Māori Youth: How culture and community provide the foundation of resilience in the face of systemic adversity. Adversity and Resilience Science, 3(3), 225–232.

Ivanich, J. D., Sarche, M., White, E. J., Marshall, S. M., Russette, H., Ullrich, J. S., & Whitesell, N. R. (2022b). Increasing native research leadership through an early career development program. Frontiers in Public Health, 10.

Kovach, M. (2010). Conversation method in Indigenous research. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 5(1), 40–48.

Krieger, N. (2020). ENOUGH: COVID-19, structural racism, police brutality, plutocracy, climate change—and time for health justice, democratic governance, and an equitable, sustainable future. In American Journal of Public Health., 110(11), 1620–1623.

Mancuso, T. (2018). Native Indian youth with substance-abusing parents: Implications of history. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 18(2), 222–229.

Mokuau, N., DeLeon P. H., Keawe’aimoku Kaholokula J., Soares S., Tsark J. U., & Haia C. (2016). Challenges and Promises of Health Equity for Native Hawaiians. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper, National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.31478/201610d

Oppong, S. (2023). Promoting global ECD top-down and bottom-up. Ethos, 51, 321–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/etho.12393

Sarche, M., & Spicer, P. (2008). Poverty and health disparities for American Indian and Alaska Native children. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1136(1), 126–136. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1425.017

Sequist, T. D. (2017). Urgent action needed on health inequities among American Indians and Alaska Natives. The Lancet, 389(10077), 1378–1379.

Tuitt, N. R., Wexler, L. M., Kaufman, C. E., et al. (2023). Unsettling settler colonialism in research: strategies centering native american experience and expertise in responding to substance misuse and co-occurring sexual risk-taking, alcohol-exposed pregnancy, and suicide prevention among young people. Adversity and Resilience Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-023-00100-5

Ullrich, J. S. (2019). For the love of our children: An Indigenous connectedness framework. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 15(2), 121–130.

Whitbeck, L. B., & Armenta, B. E. (2015). Patterns of substance use initiation among Indigenous adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 45, 172–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.01.006

Whitbeck, L. B., Walls, M., & Hartshorn, K. (2014). Indigenous adolescent development: Psychological, social and historical contexts. Psychology Press.

Whitesell, N. R., Beals, J., Mitchell, C. M., Manson, S. M., & Turner, R. J. (2009). Childhood exposure to adversity and risk of substance-use disorder in two American Indian populations: The meditational role of early substance-use initiation. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 70(6), 971–981. https://doi.org/10.15288/jsad.2009.70.971

Whitesell, N. R., Asdigian, N. L., Kaufman, C. E., Crow, C. B., Shangreau, C., Keane, E. M., Mousseau, A. C., & Mitchell, C. M. (2014). Trajectories of substance use among young American Indian adolescents: Patterns and predictors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(3), 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-0026-2

Yellow Horse, A. J., Yang, T. C., & Huyser, K. R. (2022). Structural inequalities established the architecture for covid-19 pandemic among native americans in Arizona: A geographically weighted regression perspective. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 9, 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00940-2

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (5R13DA051122 and 5R25DA050645) and the Administration for Children and Families (90PH0030), which funded this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

The original online version of this article was revised to update the acknowledgment statement.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ivanich, J.D., Ullrich, J.S., Martin, T.K.K. et al. The Indigenous Connectedness Framework for Understanding the Causes, Consequences, and Solutions to Substance Misuse in Indigenous Children’s Development. ADV RES SCI 4, 335–341 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-023-00119-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42844-023-00119-8