Abstract

All descriptions of infectious diseases affecting otters were published in the Northern Hemisphere, with no occurrence identified in neotropical otters (Lontra longicaudis). Consequently, a retrospective histopathological study using archival tissue samples from six free-living neotropical otters was done to investigate the possible occurrence of disease patterns associated with common viral infectious disease agents of the domestic dogs. Immunohistochemical (IHC) assays were designed to identify intralesional tissue antigens of canine distemper virus (CDV), and canine adenovirus-1 (CAdV-1) and canine adenovirus-2 (CAdV-2). The most frequent histopathological patterns diagnosed were interstitial pneumonia (83.33%; 6/5) and hepatocellular vacuolar degeneration (50%; 3/6). IHC identified intralesional intracytoplasmic immunoreactivity to CDV antigens in all otters evaluated, with positive immunolabeling occurring within epithelial cells of the lungs, stomach, kidneys, and liver, and skin. Intracytoplasmic CAdV-2 antigens were identified within epithelial cells of the peribronchial glands in four otters with interstitial pneumonia. These findings resulted in singular and simultaneous infections in these neotropical otters, represented the first report of concomitant infections by CDV and CAdV-2 in free-living neotropical otters from the Southern Hemisphere, and suggested that this mammalian species is susceptible to infections by viral disease agents common to the domestic dogs and may develop similar histopathologic disease patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis) is a carnivore from the family Mustelidae, subfamily Lutrinae, that inhabits several countries within the Southern Hemisphere, extending from Mexico to Uruguay [1]. Otters are semi-aquatic animals that inhabits regions with rivers, lagoons, small aquatic channels, wetlands [1], streams, swamps, and marshes [2]. Since the otter is a top-of-the-range predator in the regions it inhabits, this species is used as a biological indicator of environmental degradation [3]. Otters may compete for prey or be predated by the domestic dogs, and other wild predators, including jaguars, that inhabit the same area [1]. Moreover, otters can be infected by a wide variety of parasitic, bacterial, and viral diseases [2]. Viral diseases of the domestic dog known to occur in otters include canine distemper, CD [4, 5], infectious canine hepatitis, ICH [6], and canine parvoviral enteritis [7]. However, most of these conventional dog diseases affecting otters were previously described in North America [5, 8, 9], with findings in Europe [4], and Asia [6], and restricted information from the Southern Hemisphere [7].

Diseases caused by morbilliviruses have been studied for centuries in both humans and animals [10, 11]. CD is an infectious disease caused by canine morbillivirus (canine distemper virus, CDV) that infects a wide range of mammalian species [11,12,13]. The wide range of mammalian hosts infected, the elevated capacity for infection, and the mortality associated with infection by CDV make this infectious disease pathogen one of the most infectious viruses [10, 14]. CD is endemic in most urban cities of Brazil probably due to the presence of roaming dogs and the low vaccination coverage [15]. Descriptions of CDV-induced infections in wildlife from Brazil have been confirmed in several non-domestic dog species including the crab-eating fox, Cerdocyon thous [16], the maned wolf, Chrysocyon brachyurus [17, 18], hoary fox, Lycalopex vetulus [19], the bush dog, Cerdocyon thous [18, 20], and the country fox; Lycalopex vetulus [19]. More recently, CDV infections were identified in the southern tamandua, Tamandua tetradactyla [21], coatis, Nasua nasua [22], and neotropical felids [23], from several geographical regions of Brazil. This surge of diagnosis of CDV infections in a wide variety of species infected in Brazil may suggest that the virus is looking for additional hosts due to circulating wild-type strains of CDV [24], or that detection in mammalians other than the domestic dog from this country and the Americas is underdiagnosed or underreported [12]. Moreover, seroepidemiological studies have confirmed that several wildlife mammalian species from Brazil were in contact with CDV antibodies [18, 25].

Canine adenovirus (CAdV) belongs to the family Adenoviridae, genus Mastadenovirus [26] and contains two subtypes: CAdV-1 and -2 (CAdV-2), which are distinguished from each other by genetic, antigenic, and pathogenic characteristics [26, 27]. CAdV-1 is the etiologic agent of IHC with resulting necrotizing hemorrhagic hepatitis [26, 28]. CAdV-2 is one of the agents associated with canine infectious tracheobronchitis (kennel cough) and causes acute respiratory disease [29]. This paper presents the pathologic and immunohistochemical findings of singular and concomitant infections due to CDV and CAdV-2 in neotropical otters (Lontra longicaudis) from Southern Brazil and contributes to the documentation of infectious disease in otters worldwide.

Materials and methods

Study location and sample collection

This study analyzed tissues of neotropical otters (Lontra longicaudis) originating from the Bela Vista Biological Sanctuary (BVS), located at the banks of the lake Itaipu, Foz do Iguaçu, Paraná, Southern Brazil. The city of Foz do Iguaçu suffered major social, structural, and demographic changes due to the construction of the Itaipu Dam in 1980, resulting in an increased population density from 38.69 inhabitants per km2 to 216.38 inhabitants/km2 and the construction of veterinary hospital for the maintenance and rehabilitation of native animals [30].

Organ fragments from six neotropical otters immersed in formalin solution and maintained at the Veterinary Hospital of BVS (VH-BVS) were received for pathological investigation. The samples collected were derived from post-mortem evaluations done at the BVS by the local staff without training in diagnostic pathology. All animals were reportedly of free life, were rescued in poor health for supportive therapy at the BVS veterinary hospital, and died while hospitalized.

Histopathologic and immunohistochemical evaluations

The tissues collected at post-mortem were fixed by immersion in 10% buffered formalin solution and routinely processed for histopathological evaluation using the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain. These histological sections were examined to identify possible disease patterns associated with the occurrence of infectious disease agents of the domestic dog.

Subsequently, selected formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections were prepared to identify common intralesional viral antigens known to cause disease in dogs by immunohistochemistry (IHC) as described [22]. The list of the antibodies and the organs targeted in each otter is outlined in Table 1. The choice of the primary antibody to detect tissue antigens was defined due to the pattern of disease identified in each organ and its relationship with viral disease pathogens [22, 31]. Blocking of unspecific protein was done by hydrogen peroxide (6%; 70 ml) and distilled water (80 ml) for CDV; methyl alcohol was used for CAdV-1 and CAdV-2. After washing in distilled water, the sections were covered with protein block (Abcam, Cambridge, USA) for 30 min. Positive controls consisted of FFPE tissue sections known to contain antigens of CDV, CAdV-1, and CAdV-2 from a previous study [31]. Two negative controls were used: The first consisted of substituting the primary antibodies with their respective diluents and the second was the utilization of FFPE tissue sections with known negative immunoreactivity for CDV, CAdV-1, and 2 [31]; these included the brainstem (CDV), liver (CAdV-1), and lung (CAdV-2) from dogs that were investigated for simultaneous infections and did not contain the associated disease pathogen by IHC and molecular testing. Positive and negative controls were included in each IHC assay.

Results

Clinical history and gross findings

Clinical data and gross descriptions were only available for two otters (#3 and #6). Otter # 3 was a young female, submitted to the VH-BVS in early May 2011 by the Federal University of Paraná, Southern Brazil, for therapy and in-captivity breeding. The animal reportedly arrived weak, with uncoordinated gait and received emergency care that included food, heating, and fluid therapy, but died 2 days after arrival. The recorded gross findings included pneumonia, hyperemia of cerebral vessels, hepatomegaly, and cutaneous ulceration of the right anterior limb.

Animal (#6) was an adult male rescued in poor health at the Itaipu hydroelectric plant and was taken to the VH-BVS for emergency care in late January 2016. However, the otter died 1 day after arrival at the HV-BVS. The body condition of this otter was classified as cachectic, with dehydration estimated at 10%, a cutaneous laceration (10 × 8 cm) at the cervical region that was severely contaminated by myiasis, and severe perineal edema with multifocal areas of hemorrhage. The principal gross observations were pulmonary congestion and emphysema and an enlarged, pale liver.

Histopathologic disease patterns observed in neotropical otters

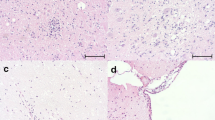

The main histopathologic patterns are summarized in Table 2 and are based on the tissues available for each neotropical otter. The most frequent histopathological pattern diagnosed was interstitial pneumonia (83.33%; 6/5), characterized by moderate to severe thickening of the alveolar septa due to the proliferation of type-2 pneumocytes and the influx of lymphocytic and histiocytic inflammatory cells (Fig. 1A). Additional pulmonary findings included severe congestion of alveolar capillaries, alveolar and interstitial edema, bronchiectasis, and hyperplasia of the bronchi-associated lymphoid tissue; moderate lymphocytic bronchitis was identified in otter #3. Syncytial cells and viral inclusion bodies were not observed.

Histopathological and immunohistochemical findings observed in neotropical otters infected by canine distemper virus (CDV) and canine adenovirus-2. There is interstitial pneumonia (A) and positive intracytoplasmic immunoreactivity to CDV within chondrocytes (red arrows) and bronchial epithelial cells (black arrows) of the lung (B); insert showing degenerated bronchial epithelial cells with positive immunoreactivity for CDV antigens. Closer view of positive intracytoplasmic immunoreactivity to CDV antigens within chondrocytes (C) and leukocytes (D) of the lung. Observed intracytoplasmic immunoreactivity to CDV antigens within tubular epithelial cells of the kidney (E) and to canine adenovirus-2 antigens (F) within epithelial cells of the peribronchial glands. A Hematoxylin and eosin stain. B-F Immunoperoxidase counterstained with hematoxylin. Bars: A, 20 µm; B, 50 µm; C-F, 10 µm; insert 10 µm

Hepatic fragments were only available for four otters (#1, #2, #3, and #5). Histopathologic evaluation of the liver of otter #1 revealed severe, random necrotizing hepatitis, affecting more than 80% of the hepatic lobule. Additional histopathological findings observed were severe hepatocellular vacuolar degeneration (#1, #2, and #3) and moderate periportal hepatitis (otter #5).

Fragments of the stomach were available for three otters (animal #1, #5, and #6). Histopathologic evaluation revealed moderate to severe submucosal edema, moderate dilation of lymphatic vessels, and moderate lymphocytic and histiocytic inflammatory infiltrations. In addition, there was mild to moderate perivascular lymphocytic accumulations at the connective tissue of the stomach wall, increase cellularity of the Auerbach plexuses, with mild neuronal degeneration in otter #1. Additional histopathologic findings include interstitial lymphocytic nephritis (animal #6) and parakeratotic hyperkeratosis with formation of multifocal keratin horns and vacuolar degeneration of keratinocytes in otter #3.

Immunohistochemical demonstration of viral antigens within tissues of neotropical otters

The distribution of the positive immunoreactivity for each antibody evaluated is given at Table 3, with the identification of intralesional antigens of CDV (n = 6) and CAdV-2 (n = 4) in multiple tissues of these otters. Intracytoplasmic intralesional immunoreactivity for CDV antigens was observed primarily within bronchiolar epithelium (#1-5; Fig. 1B), epithelial cells of the stomach (#1, 5, and 6), pulmonary lymphocytes and histiocytes (#1, 2, and 3), and tubular and endothelial cells of the kidney (#3 and 5; Fig. 1C). Additionally, CDV antigens were identified within lymphocytes, macrophages, and degenerated keratinocytes of the skin of otter #3. Positive intracytoplasmic immunoreactivity to CAdV-2 antigens was observed within the epithelial cells of the peribronchial glands of otters (#1, 2, 3, and 5; Fig. 1D) with interstitial pneumonia. Positive immunoreactivity to CAdV-1 antigens was not identified in any of the tissues identified, even in otter #1 with necrotizing hepatitis.

Additionally, the concomitant findings of several disease patterns associated with the intralesional IHC detection of viral disease antigens suggest that these otters were infected by several disease pathogens, resulting in singular (#4 and 6) and concomitant (#1, 2, 3, and 5) infections.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrated the occurrence of singular and concomitant viral infections in neotropical otters from Southern Brazil. The IHC identification of antigens of CDV and CAdV-2 recovered from tissues maintained for extensive periods in formalin solution confirmed these infections; similar findings were previously described by our group from tissues immersed in formalin solution for up to 23 years [22, 23, 28]. Consequently, IHC can be used to efficiently recuperate tissue antigens of disease pathogens from FFPE archival blocks and/or tissue, is the recommended strategy to diagnose infections by CAdV-2 [32], and is a well-established diagnostic method for CDV [13, 31, 33]. This in situ diagnostic strategy is superior to molecular characterization since it can effectively identify tissue antigens within histologic lesions, thereby confirming infection. Although antigenic retrieval was possible with subsequent demonstration of positive immunoreactivity for these viral disease pathogens, distinct immunolabeling was hindered due to improper and prolonged tissue fixation and tissue integrity. Additionally, molecular amplification of viral nucleic acids would have contributed towards the diagnosis and the possible identification of the linage of CDV, but prolonged formalin fixation resulted in frustrated attempts to successfully amplify viral material from the FFPE tissue blocks.

The infectious disease pathogens identified in these otters were associated with disease pattern similar to those described in the domestic dog with interstitial pneumonia due to CDV [29, 31, 34, 35] and necrotizing hepatitis associated with CAdV-1 [26]. Moreover, interstitial pneumonia was diagnosed in wildlife species infected by CDV [8, 22, 36, 37], suggesting that this disease pattern may be similar between mammalian species infected with CDV. However, syncytial cells and viral inclusion bodies described in interstitial pneumonia of otters [8, 37] were not observed during this study.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, these findings represent the first documentation of infections by CDV and CAdV-2 in otters from the Southern Hemisphere, confirming that otters are susceptible to a wide range of infectious diseases [2]. Infections resulting in CDV-associated encephalitis occurred in sea otters (Enhydra lutris) from several locations within the USA, due to a combination of histopathologic and IHC findings, and molecular characterization [5]. Moreover, diagnostic IHC associated with molecular characterization confirmed CDV-induced interstitial pneumonia in river otters (Lontra canadensis) from British Columbia [8]. Additionally, a morbillivirus-associated encephalitis was described in northern sea otters (Enhydra lutris kenyoni) salvaged from the Washington coastline, USA [38], and there is serological evidence of several viral infections, including CDV, in the North American river otter, Lontra canadensis [9]. Similar cases of CDV-associated diseases were identified in otters from Europe [4, 37]. Alternatively, there seems to be few documented cases of adenoviral infections in otters, as herein presented. There is the confirmation of CAdV-1-induced necrotizing hepatitis in a Eurasian river otter (Lutra lutra) with the identification of viral particles by transmission electron microscopy and molecular characterization [6] and serological evidence of CAdV-1 detection in the North American river otter [9]. In one otter from this study, there was the typical pattern of histologic lesion suggestive of CAdV-1 infection [26], but viral antigens were not identified by IHC.

Notwithstanding the above, these results herein presented will contribute towards the documentation and understanding of infectious diseases in otters and suggest that otters are highly susceptible to infections by common viral disease pathogens of the domestic dog. Nevertheless, it must be highlighted that clinical manifestations of disease were only available for two otters (#3 and 6); otter #3 described as having uncoordinated gait and hyperemia of cerebral vessels. Although incoordination is a frequent clinical manifestation of neurological distemper [15, 34], brain fragments were not available to confirm CDV-induced encephalitis in this animal with disseminated IHC evidence of CDV antigens in multiple organs. Nonetheless, since we have previously identified CDV-induced infections in coatis [22] and neotropical felids [23] from this conservational area, prophylactic measures should be implemented to prevent mass mortality associated with CD in susceptible wildlife populations due to the close proximity of the domestic dog and the possibility of contamination by the spill-over effect [39]. Furthermore, the negative effect of viral disease in conservational areas [12], such as the BVS, cannot be overlooked.

How these otters became infected by multiple viral disease pathogens is currently unknown. Neotropical otters, due to their semi-aquatic habit [1, 40], can coinhabit areas containing large felids [1], as is the case at the BVS. As indicated above, we have diagnosed viral [22, 23] and bacterial [28] diseases in several populations of wildlife maintained within the BVS, and have theorized that the close proximity of the BVS to the adjacent urban district that has a significant population of roaming dogs could have contributed to infections in susceptible animal populations maintained within this sanctuary [22]. Infection would probably be due to the spill-over effect [39], considering that CD is probably maintained in urban regions of Brazil due to unvaccinated roaming dogs [15, 35], and is one of the main sources of infection to susceptible hosts [11]. Furthermore, roaming domestic dogs were also incriminated with CPV-2 infection from Brazil [7], and were associated with seropositivity to CDV in several wildlife species form Brazil [18, 25]. Alternatively, infection could have occurred through contact with other wild animals that inhabit the same space and compete for food or act as prey [1], considering that CDV was identified in coatis [22] and neotropical felids [23] from this protected region.

In conclusion, histopathologic evaluation identified disease patterns consistent with those described in the domestic dogs infected with CDV within the lungs of all neotropical otters. Immunohistochemistry identified intralesional tissue antigens of CDV and CAdV-2 in multiple tissues of these otters, confirming singular and dual infections. These findings suggest that neotropical otters can serve as a possible host for CDV and CAdV, and that prophylactic measures should be implemented within the BVS to reduce CDV-associated mortality to susceptible wildlife species.

References

Rheingantz ML, Santiago-Plata VM, Trinca CS (2017) The Neotropical otter Lontra longicaudis: a comprehensive update on the current knowledge and conservation status of this semiaquatic carnivore. Mammal Rev 47(4):291–305

Kimber KR, Kollias G (2000) Infectious and parasitic diseases and contaminant-related problems of North American river otters (Lontra canadensis): a review. J Zoo Wildl Med 31(4):452–472

Latorre-Cardenas MC, Gutiérrez-Rodríguez C, Lance SL (2020) Isolation and characterization of 13 microsatellite loci for the Neotropical otter, Lontra longicaudis, by next generation sequencing. Mol Biol Rep 47(1):731–736

Madsen AB, Dietz HH, Henriksen P, Clausen B (1999) Survey of Danish free living otters Lutra lutra – a consecutive collection and necropsy of dead bodies. IUCN Otter Spec Group Bull 163(2):65–76

Thomas N, White CL, Saliki J et al (2020) Canine distemper virus in the Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris) population in Washington State, USA. J Wildf Dis 56(4):873–883

Park NY, Lee MC, Kurkure NV, Cho HS (2007) Canine adenovirus type 1 infection of a Eurasian River Otter (Lutra lutra). Vet Pathol 44(4):536–539

Echenique JVZ, Soares MP, Mascarenhas CS et al (2018) Lontra longicaudis infected with canine parvovirus and parasitized by Dioctophyma renale. Pesquisa Veterinária Brasileira 38:1844–1848

Mos L, Ross P, McIntosh D, Raverty S (2003) Canine distemper virus in river otters in British Columbia as an emergent risk for coastal pinnipeds. Veterinary Record 152(8):237–239

Kimber KR, Kollias GV, Dubovi EJ (2000) Serologic survey of selected viral agents in recently captured wild North American river otters (Lontra canadensis). J Zoo Wildl Med 31(2):168–175

Uhl EW, Kelderhouse C, Buikstra J et al (2019) New world origin of canine distemper: interdisciplinary insights. Int J Paleopathol 24:266–278

Beineke A, Baumgartner W, Wohlsein P (2015) Cross-species transmission of canine distemper virus-an update. One health (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 1:49–59

Rendon-Marin S, Martinez-Gutierrez M, Suarez JA, Ruiz-Saenz J (2020) Canine Distemper virus (CDV) transit through the Americas: need to assess the impact of CDV infection on species conservation. Front Microbiol. 11(810)

Deem SL, Spelman LH, Yates RA, Montali RJ (2000) Canine distemper in terrestrial carnivores: a review. J Zoo Wildl Med 31(4):441–451

Cosby SL (2012) Morbillivirus cross-species infection: is there a risk for humans? Futur Virol 7(11):1103–1113

Headley SA, Amude AM, Alfieri AF, Bracarense APF, Alfieri AA (2012) Epidemiological features and the neuropathological manifestations of canine distemper virus-induced infections in Brazil: a review. Semina: Ciências Agrárias 33(5):1945–1978

Rego AAMS, Matushima ER, Pinto CM, Biasia I (1997) Distemper in Brazilian wild canidae and mustelidae: case report. Braz J Vet Res Anim Sci 34:256–258

Deem SL, Emmons LH (2005) Exposure of free-ranging maned wolves (Chrysocyon brachyurus) to infectious and parasitic disease agents in the Noel Kempff Mercado National Park. Bolivia J Zoo Wildl Med 36(2):192–197

Furtado MM, Hayashi EM, Allendorf SD et al (2016) Exposure of free-ranging wild carnivores and domestic dogs to canine distemper virus and parvovirus in the Cerrado of Central Brazil. EcoHealth 13(3):549–557

Megid J, Teixeira CR, Amorin RL et al (2010) First identification of canine distemper virus in hoary fox (Lycalopex vetulus): pathologic aspects and virus phylogeny. J Wildf Dis 46(1):303–305

Megid J, de Souza VA, Teixeira CR et al (2009) Canine distemper virus in a crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous) in Brazil: case report and phylogenetic analyses. J Wildlife Dis 45(2):527–530

Lunardi M, Darold GM, Amude AM et al (2018) Canine distemper virus active infection in order Pilosa, family Myrmecophagidae, species Tamandua tetradactyla. Vet Microbiol 220:7–11

Michelazzo MMZ, Oliveira TES, Viana NE et al (2020) Immunohistochemical evidence of canine morbillivirus (canine distemper) infection in coatis (Nasua nasua) from Southern Brazil. Transbound Emerg Dis 67(S2):178–184

Viana NE, Michelazzo MMZ, Oliveira TES et al (2020) Immunohistochemical identification of antigens of canine distemper virus in neotropical felids from Southern Brazil. Transbound Emerg Dis 67:149–153

Harder TC, Osterhaus ADME (1997) Canine distemper virus — a morbillivirus in search of new hosts? Trends Microbiol 5(3):120–124

Nava AF, Cullen L Jr, Sana DA et al (2008) First evidence of canine distemper in Brazilian free-ranging felids. EcoHealth 5(4):513–518

Greene CE (2012) Infectious canine hepatitis and canine acidophil cell hepatitis. In: Greene, C.E. (ed). Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. St. Louis, Missouri, Elsevier: 42-47

Balboni A, Verin R, Morandi F et al (2013) Molecular epidemiology of canine adenovirus type 1 and type 2 in free-ranging red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) in Italy. Vet Microbiol 162(2):551–557

Headley SA, Oliveira TES, Zanim MMM et al (2018) Immunohistochemical and molecular evidence of putative Neorickettsia infection in coatis (Nasua nasua) from Southern Brazil. J Zoo Wildl Med 49(3):535–541

Caswell JL, Williams KJ (2016). Viral respiratory diseases of dogs. In: Maxie, M.G. (ed). Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s pathology of domestic animals. St. Louis, Missouri, Elsevier.Vol. 2: 574-577

Conte CH (2013) Do milagre econômico á construção de Itaipu: configurando a cidade de Foz do Iguaçu/PR. Revista Economia e Desenvolvimento. 12(2):166–192

Headley SA, Oliveira TES, Pereira AHT et al (2018) Canine morbillivirus (canine distemper virus) with concomitant canine adenovirus, canine parvovirus-2, and Neospora caninum in puppies: a retrospective immunohistochemical study. Sci Rep 8(1):13477

Yoon SS, Byun JW, Park YI et al (2010) Comparison of the diagnostic methods on the canine adenovirus type 2 infection. Basic Appl Pathol. 3(2):52–56

Haines DM, Martin KM, Chelack BJ et al (1999) Immunohistochemical detection of canine distemper virus in haired skin, nasal mucosa, and footpad epithelium: a method for antemortem diagnosis of infection. J Vet Diagn Invest 11(5):396–399

Greene CE, Vandevelde M (2012) Canine distemper. In: Greene CE (ed) Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. Elsevier, St Louis, pp 25–42

Headley SA, Graça DL (2000) Canine distemper: epidemiological findings of 250 cases. Braz J Vet Res Anim Sci 37:136–140

Alexander KA, Appel MJ (1994) African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) endangered by a canine distemper epizootic among domestic dogs near the Masai Mara National Reserve Kenya. J Wildf Dis 30(4):481–485

De Bosschere H, Roels S, Lemmens N, Vanopdenbosch E (2005) Canine distemper virus in Asian clawless otter (Aonyx cinereus) littermates in captivity. Vlaams Diergeneeskundig Tijdschrift 74:299–302

White CL, Lankau EW, Lynch D et al (2018) Mortality trends in northern sea otters (Enhydra lutris kenyoni) collected from the coasts of Washington and Oregon, USA (2002–15). J Wildf Dis 54(2):238–247

Daszak P, Cunningham AA, Hyatt AD (2000) Emerging infectious diseases of wildlife-threats to biodiversity and human health. Science 287(5452):443–449

Trinca CS, de Thoisy B, Rosas FC et al (2012) Phylogeography and demographic history of the Neotropical otter (Lontra longicaudis). J Hered 103(4):479–492

Acknowledgements

Permission to use tissues from coatis maintained at the Bela Vista Biological Sanctuary for scientific purposes was obtained from ITAIPU Binacional (Agreement E/CD 037256/16) due to an understanding established between the Department of Preventive Medicine, Universidade Estadual de Londrina and ITAIPU Binacional. All methods used during this investigation were approved by and carried out in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the Universidade Estadual de Londrina relative to the usage of animals submitted for autopsy, biopsy, and/or clinical evaluation.

Funding

SA Headley is a recipient of the National Counsel of Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq; Brazil) fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Mello Zanim Michelazzo, M., Martinelli, T.M., de Amorim, V.R.G. et al. Canine distemper virus and canine adenovirus type-2 infections in neotropical otters (Lontra longicaudis) from Southern Brazil. Braz J Microbiol 53, 369–375 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42770-021-00636-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42770-021-00636-7