Abstract

In recent years, a lack of relevant contemporary Canadian data sources has led to a gap in our understanding of the experience of parental separation or divorce among children. Using the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth, we aim to update our understanding of this topic. Through cross-sectional analysis, we estimate the prevalence of the experience of parental breakup among children and describe the characteristics that correlate with this experience. Among children who have experienced parental breakup, we detail the prevalence of various types of parenting time arrangements as measured through the type of contact with the other parent not living in the surveyed household (equal, regular, irregular, remote only, none). Finally, a series of logistic regressions are employed to estimate the differential probability of children exhibiting mental health or functional difficulties according to (a) having experienced parental separation or divorce and (b) their subsequent type of contact with the other parent. Findings indicate that 18% of children aged 1–17 in Canada in 2019 had experienced the separation or divorce of their parents. The most common subsequent parenting time arrangement was to have regular visits with the other parent. Children who had experienced parental breakup were found to have significantly higher odds of exhibiting mental health or functional difficulties. Following parental breakup, the relative odds of having mental health or functional difficulties was highest among children who had irregular contact with the other parent.

Dans les dernières années, le manque de données canadiennes contemporaines et pertinentes a nui à notre compréhension de l’expérience de la séparation ou du divorce des parents chez les enfants. En utilisant l’Enquête canadienne sur la santé des enfants et des jeunes de 2019, notre objectif est de mettre à jour notre compréhension de ce sujet. Grâce à des analyses transversales, nous estimons la prévalence de l’expérience de la rupture parentale chez les enfants et décrivons les caractéristiques qui sont corrélées avec cette expérience. Parmi les enfants qui ont vécu une rupture parentale, nous détaillons la prévalence de divers types d’arrangements du temps parental, mesurés par le type de contact avec l’autre parent ne vivant pas dans le ménage enquêté (égal, régulier, irrégulier, à distance seulement, aucun). Enfin, une série de régressions logistiques est utilisée pour estimer la probabilité différentielle que les enfants présentent des problèmes de santé mentale ou des difficultés fonctionnelles selon (a) qu’ils ont vécu la séparation ou le divorce de leurs parents et (b) le type de contact qu’ils ont eu avec l’autre parent par la suite. Les résultats indiquent que 18% des enfants âgés de 1 à 17 ans au Canada en 2019 avaient vécu la séparation ou le divorce de leurs parents. L’arrangement de temps parental le plus courant par la suite était d’avoir des visites régulières avec l’autre parent. On a constaté que les enfants qui avaient vécu une rupture parentale avaient significativement plus de chances de présenter des difficultés de santé mentale ou fonctionnelles. Après une rupture parentale, les enfants qui avaient des contacts irréguliers avec l’autre parent étaient les plus susceptibles d’avoir des problèmes de santé mentale ou des difficultés fonctionnelles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

As many nations move through the second demographic transition, societal changes such as the assertion of individual autonomy, the increasing popularity of cohabitation in lieu of marriage, the de-stigmatisation of divorce, and greater gender equality have contributed in part to an increasing prevalence of union dissolution (Lesthaeghe, 2020; Lopez Narbona et al., 2021). This phenomenon has led to growing interest in children who have experienced the separation or divorce of their parents. Yet in the Canadian context, there has been little empirical research on this phenomenon in recent years. A lack of contemporary nationally representative data has hampered efforts to monitor the prevalence of the experience of parental separation or divorce among children, the types of parenting arrangements in place for children following this experience, and associations with children’s well-being.

There is a general consensus in the literature that as a result of increasing family instability, households are now more likely to be linked through the shared parenting of children (Coulter et al., 2016). In turn, the term ‘multi-parenthood’—in which a child often has several parents, each performing different roles—may more accurately represent the complexity of some children’s family situation (Letablier & Wall, 2018). However, there is an absence of empirical data about these ‘hidden’ living arrangements, limiting our ability to address questions regarding the emotional, cognitive, and financial wellbeing of children and parents who experience them (Coulter et al., 2016; Letablier & Wall, 2018; Strohschein, 2017). Currently, social policies and programs directed at certain populations such as one-parent families are often made on the basis of household composition, omitting the possibility of children dividing their time across multiple households. This ‘address-based’ approach (Strohschein, 2017) to determining program eligibility and policy needs masks the considerable heterogeneity in the financial security, social resources, and day-to-day realities and complexities of families who engage in shared (or co-) parenting versus solo parenting (Letablier & Wall, 2018; Palmer, 2002; Strohschein, 2017).

In this article, we first review the state of knowledge of the experience of parental breakup among children, with a focus on the Canadian context. Taking into consideration what the literature has revealed with respect to general associations and information gaps, we profit from the release of the 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth (CHSCY) which permits us to improve our understanding of children in Canada who have experienced parental separation or divorce. Specifically, we first estimate the prevalence of this experience among children aged 1 to 17, and describe the characteristics of those children and their families. We secondly estimate, among children who experienced parental separation or divorce, the distribution of the type of contact with their other parentFootnote 1, again describing the characteristics associated with each type of contact. Lastly, we conduct a series of binary logistic regression models to whether the odds that children have poor general mental health, symptoms of depression, symptoms of anxiety, or behavioural difficulties differ for (a) those who have experienced parental separation and divorce, compared with those that have not, and (b) those who have regular contact, irregular contact, remote contact only, or no contact with the other parent following parental breakup, compared to those children who have equal contact with both parents following parental breakup.

1 Literature Review

1.1 Prevalence of Parental Separation or Divorce Among Children in Canada and Parenting Time Arrangements

In Canada, there has been relatively little information made available on the prevalence of union dissolution in recent years, much less for those separations or divorces involving children (Pelletier, 2017). The last year for which Statistics Canada published information on the annual number of new divorces registered was 2008Footnote 2, and there is currently no national data source which permits the calculation of annual rates of common-law relationship dissolution.

The National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth (NLSCY), conducted between 1994 and 2009, collected information on children’s family history and living arrangements. Using the NLSCY, Juby et al. (2004) estimated that by age 15, close to 30% of children born to a couple family during the early 1980s had experienced their parents’ separation; the authors also document a rapid rise in separation during the 1980s followed by a levelling off in the early 1990s. The NLSCY also revealed that despite the fact that common-law unions have been steadily gaining popularity in CanadaFootnote 3, those involving children were more likely to dissolve than married unions with children (Marcil-Gratton & Le Bourdais, 1999). However, the stability of the two union types has somewhat converged over time (Pelletier, 2016). Following the end of the NLSCY over a decade ago, a gap has re-emerged in Canada with respect to the empirical measurement of parental separation or divorce among children.

Two key Canadian data sources on the topic of family—the Canadian Census of Population and the General Social Survey (GSS) — Family cycles—provide insight on general trends in family diversity and living arrangements. Census data indicates that close to 2 in 10 children aged 14 and under in 2016 lived in a one-parent family, with an additional 1 in 10 living in a stepfamily (Statistics Canada, 2017a). The census has also revealed considerable regional diversity in children’s family structure: among the provinces and territories, the incidence of children living in one-parent families is highest in Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nunavut, and Yukon, while stepfamily arrangements are more prevalent among children living in Quebec and New Brunswick (Statistics Canada, 2017a). However, the census lacks the content necessary to measure the prevalence of the experience of parental divorce or separation among children. While one may assume that most one-parent families and stepfamilies were formed after the divorce or separation of a child’s parents, this may not necessarily be the case: a growing share of children in one-parent families live with a parent who has never previously marriedFootnote 4 (Bohnert et al., 2014) and the majority of multiple-partner fertility trajectories in Canada start with a first birth outside of union (Fostik & Le Bourdais, 2020).

The GSS provides rich information on the relationship history of adult respondents (Statistics Canada, 2019a; b) including parenting arrangements after separation or divorce (Sinha, 2014; Statistics Canada, 2021a). However, this information is obtained with the parent as the unit of analysis, precluding the estimation of the number of children who have experienced parental divorce or separation.

Administrative data sources such as tax data have been used in the past to identify and follow the conjugal trajectories of adolescents whose parents divorced (Corak, 2001). More recently, however, Margolis et al (2019) conclude that over time, the rates of divorce are increasingly underestimated in the (T1FF) tax data, particularly among younger adults—a finding echoed in a recent Statistics Canada internal study examining concordance in the divorced population between the T1FF and the 2016 Census (Bérard-Chagnon et al., n.d.). In theory, administrative court records, such as those pertaining to court-ordered custody arrangements, could be used to estimate how many children have experienced parental divorce if not separation from a cohabiting union. However, current sources have incomplete coverage and this limitation is likely to only increase further with time.Footnote 5

Given the scarcity of information about the prevalence of the experience of parental separation or divorce among children in Canada, there are considerable gaps in our understanding of the subsequent parenting plansFootnote 6 in place for the country’s children, and specifically the occurrence and distribution of shared parenting time arrangementsFootnote 7—defined in this study as a situation where the child splits his or her time between each parent’s place of residence to some extent (de Torres Perea, 2021; Pelletier, 2017).

More recent studies have focused on different types of information with respect to shared parenting time arrangements, as well as different populations and geographical regions rather than a comprehensive national portrait (Bala et al., 2017). Categorization of the various levels of shared parenting is not standardized within the literature generally nor within Canadian data sources specifically.Footnote 8 This situation may partly reflect Canada’s status as a federation with a complex interaction of federal and provincial parenting laws and statutes (Bala et al., 2017). In the absence of consensus on the operationalization of this basic measure, it is difficult to attempt international comparisons of the proportion of children who split their time living in two different parental homes.

Despite the limited data from which to establish the precise magnitude of trends, there is nonetheless general agreement that the prevalence of more equally shared parenting time has grown in Canada, with significant interprovincial variation in this regard (Sinha, 2014; Bala et al., 2017, Pelletier, 2017; Statistics Canada, 2021a; Steinbach, 2019; Vezzetti, 2021; de Torres Perea, 2021). As with the proximate determinants of parental divorce and separation, the growth of shared parenting time is theorized to reflect in large part growing gender equality in Canada and other countries, particularly mothers’ increased labour force participation and fathers’ greater involvement in their child’s upbringing (Steinbach, 2019). As these trends develop and new policies like dedicated second-parent leaveFootnote 9 become more widely utilized, it is anticipated that shared parenting time is likely to continue growing in prevalence in the years to come (Kitterod & Lyngstad, 2012; Letablier & Wall, 2018).

1.2 Correlations Between Parental Separation or Divorce, Subsequent Parenting Time Arrangements and Child Well-Being

The breakup of parents’ couple relationship represents a major transition in the life of the child, the parents, and the family (Palmer, 2002). On average, children who have experienced parental separation or divorce have been found to be at increased risk for social, educational, mental health and functional difficulties (Braver & Votruba, 2021; Ferrer & Pan, 2020; Ram & Hou, 2003; Strohschein, 2005, 2012), financial insecurity, interparental conflict, and feelings of loss and guilt (Palmer, 2002). The dissolution of the parents’ couple relationship may also have long-lasting consequences; past studies have linked the experience of parental divorce to a subsequent greater risk of divorce, i.e., the intergenerational transmission of divorce (Corak, 2001) and to relatively lower contact between adult children and their male parents (Statistics Canada, 2020a).

However, the probability of union breakup is itself highly selective on socioeconomic status, being more likely to occur among couples with lower socioeconomic status in recent decades (McLanahan, 2004; McLanahan & Jacobsen, 2015). As a result, causal determinations with respect to subsequent child well-being must be approached carefully, particularly in analyses based on cross-sectional data which cannot account for the characteristics of the child and family prior to the breakup event. The possibility of negative outcomes for children following parental separation or divorce also depends on the context of the family breakup including the ethnocultural and surrounding societal milieu, the subsequent complexity of the child’s family structure, and the child’s age, gender, and ability to cope with stress (Fomby et al, 2021; Kline Pruett & DiFonzo, 2014; Kline Pruett et al., 2014; Mandemakers & Kalmijn, 2014; Palmer, 2002; Thomson & McLanahan, 2012). In some cases, family breakup can be beneficial when it represents an opportunity to reduce previously-adverse conditions on family members such as regular conflict or an abusive home environment (Thomson & McLanahan, 2012).

There is a general consensus in the literature that following parental separation or divorce, shared parenting time—in comparison with sole parenting—is associated with comparatively better well-being of children (Baude et al., 2016; Bjarnason & Arnarsson, 2011; Nielsen, 2014, 2018, 2021; Steinbach, 2019; Vezzetti, 2021). It has been found that shared parenting time arrangements bring numerous social and psychological benefits to parents in the form of more help, financial resources, free time, and a more equitable sharing of childcare responsibilities. In turn, children tend to have better communication with parents under shared parenting circumstances compared to sole parenting situations. Somewhat counter-intuitively, children may even experience higher quality and greater quantity of time with each individual parent (particularly in the case of fathers) under shared parenting circumstances compared with those in an ‘intact’ family (Bjarnason & Arnarsson, 2011; Koster & Castro-Martin, 2021).That said, it is also apparent that there is no ‘one size fits all” parenting time arrangement that is considered best for all families and children; the most effective parenting arrangement after separation is ‘inescapably case-specific” and needs to take into account the child’s current developmental needs, the protection of family members from conflict and violence, and the preservation of family preferences (Kline Pruett & DiFonzo, 2014).

As when examining the impacts of parental breakup on children, the influence of selection effects impedes empirical efforts to isolate the impacts of shared parenting time arrangements on children. Because the underlying factors that lead ex-spouses and partners to arrive at certain post-breakup arrangements may also affect parental resources and child wellbeing, it is difficult to disentangle the precise causal mechanisms at work in cross-sectional data (Braver & Votruba, 2021; Thomson & McLanahan, 2012). Even pre-separation measures of well-being may pick up the effects of a pending separation or divorce (Strohschein, 2005, 2012; Thomson & McLanahan, 2012). Previous studies have found that the likelihood of shared parenting time arrangements is increased when the parents have higher socioeconomic status (Juby et al., 2005; Pelletier et al., 2017; Steinbach, 2019; Strohschein, 2017), when the mother engages in paid work (Pelletier et al., 2017), when parental conflict is lower and children are younger (Bala et al., 2017; Palmer, 2002; Steinbach, 2019), and following informally negotiated arrangements rather than court-ordered ones (Juby et al., 2004). That said, more recent studies by Nielsen (2021) and Braver and Votruba (2021) challenge the notion that selection effects drive the relatively better outcomes of children in shared parenting time arrangements compared to sole parenting arrangements. For instance, Nielsen (2021) posits that contrary to popular belief, parental conflict is not significantly lower between parents who engage in shared parenting time.

In addition to the potential spurious influence of selection effects, various moderating factors have been found to play a role in the well-being of children who split their time between two parental households. Factors that are conducive to beneficial shared parenting time include geographic proximity of the two parental residences, family-friendly parental work schedules, and a willingness on the part of parents towards flexibility (Nielsen, 2014; Steinbach, 2019). As with the child’s experience of the preceding parental breakup event, age has been found to moderate the child’s experience of shared parenting time. Adolescent children tend to express more dissatisfaction with living in two homes than younger children (Nielsen, 2014). Despite some debate in the literature, more recent analyses seem to agree that shared parenting time appears to be relatively beneficial to the well-being of young children, even those of the very youngest ages (Steinbach, 2019). Gender may also play a moderating role; in a meta-analysis, Nielsen (2014) found evidence that girls tend to have worsened emotional outcomes than boys under shared parenting time arrangements.

Lastly, dynamic changes in the family structure and living arrangements of the child are likely to influence his or her experience of shared parenting. For example, when a parent acquires new family responsibilities in the form of a new partner, child or stepchild, they may exhibit lower parental engagement (Koster et al., 2021) and/or have lower financial resources available (Manning & Smock, 2000).

2 Research Questions

In the present study, we aim to improve our understanding of children in Canada who have experienced parental separation or divorce through the examination of three interrelated questions:

-

1.

How prevalent is the experience of parental separation or divorce among children, and what are the characteristics of children and families who have experienced parental breakup?

-

2.

Following the breakup of their parents, what types of parenting time arrangements are most common for children?

-

3.

How does the child’s experience of parental separation or divorce, and subsequent parenting time arrangement, associate with the odds that a child is reported to have mental health or behavioural difficulties, after controlling for the characteristics of the child and their family?

3 Method

3.1 Data Source

Data were drawn from Statistics Canada’s 2019 Canadian Health Survey on Children and Youth (CHSCY), a national cross-sectional sample survey focused on the physical and mental health of children in Canada. The sampling frame for the CHSCY is the Canada Child Benefit file. The target population includes persons aged 1 to 17 as of 31 January 2019, living in the ten provinces and the three territories. Excluded from the survey’s coverage are children and youth living on First Nation reserves and other Indigenous settlements in the provinces, children and youth living in foster homes, and the institutionalized population. The survey has a probabilistic sampling design and is representative of the population of Canadian youth aged 1 to 17 living in private households. The overall response rate was 52%, resulting in a total sample size of N = 47,871. Survey sample weights were applied so that the analyses would be representative of the Canadian population.Footnote 10 Data were collected from February to August 2019 via electronic questionnaire or telephone.

The person most knowledgeable about the child—referred to in this article as the parent or responding parent—was selected to answer questions about the child. In 96.2% of cases, the person most knowledgeable was a birth parent; other relationships included adoptive parent, step parent, foster parent, or ‘other’. There is only one selected child per responding parent.

The full analytical sample was restricted to children with a non-missing response for the key outcome variable parental separation or divorce (described in the following section). This resulted in an unweighted N of 47,764 children.

For the analyses focused on type of contact with the other parent—i.e., for those children who had experienced parental separation or divorce—some additional restrictions were made to the analytical subsample. Firstly, a small percentage of parents indicated that their child had experienced the separation or divorce of his or her parents but was nonetheless currently living with both biological parents; these cases were excluded from analyses focused on type of contact with the other parent. Also excluded from this analytical subsample were adoptees, children in foster homes, and those who had experienced the death of a parent or sibling.Footnote 11 Together these exclusions reduced the size of the weighted analytical subsample from 1,186,455 to 997,500 (− 16%).

3.2 Measures

3.2.1 Parental Separation or Divorce and Contact Following Separation or Divorce

Parental separation or divorce was assessed using the question ‘has this child experienced the separation or divorce of a parent?’ (yes/no).

Type of contact with the other parent was assessed through a combination of survey questions. Parents completed a roster of all household members, specifying the relationship of each household member to the target child. Parents who indicated that the child did not live with two biological or adoptive parents were asked whether there was another parent or guardian outside the home with whom the child has contact. Those who answered ‘no’ to the former question were considered to have no contact. Those who answered ‘yes’ were asked ‘What type of contact does the child now have with his other parent or guardian?’ with response options ‘lives equally with both parents or guardians’; ‘regular visits, e.g., every week, every two weeks’; ‘irregular visits’; ‘video call or chat, telephone, letter or email contact only’; ‘other’. After examining the characteristics of the small number of participants for whom the option ‘other’ was recorded, it was decided to include this category with the ‘video call or chat, telephone, letter or email contact only’.

3.2.2 Child and Family Characteristics

The child’s sex at birth (male, female) and age (grouped as: 1–4 years, 5–11 years, and 12–17 years) were reported by the parent. We also assess the significance of the responding parent’s sex at birth (male, female) and responding parent’s age (grouped as 15–24 years, 25–34 years, 35–44 years, 45–54 years, and 55 years or older). In the logistic models, age group of parent was removed as a covariate due to its high collinearity with age group of child.

Place of residence is examined by the province or territory of residence and residence in a rural area, derived based on participants’ postal code.Footnote 12 The logistic models did not include covariates indicating residence in the individual provinces and territories due to sample size limitations. The exception was the province of Quebec; given the relatively high prevalence of the experience of parental separation or divorce among children in this province, its relatively large population size, and its unique sociocultural identity within CanadaFootnote 13 (Laplante, 2016), we opted to include a dichotomous variable indicating residence in Quebec versus the rest of Canada.

We measure Indigenous identity of children using the (parent-reported) question: ‘Is this person an Aboriginal person, that is, First Nations (North American Indian), Metis, or Inuk (Inuit)?’ (‘yes’/ ‘no’).

Parent’s immigrant status was assessed using the question: ‘Where was this person born?’ (with responses: ‘born in Canada’; ‘born outside Canada’). For children who did not have Indigenous identity, children’s membership in a racialized group was derived from parents’ reporting of the population groups to which the child belongs (White; South Asian; Chinese; Black; Filipino; Arab; Latin American; Southeast Asian; West Asian; Korean; Japanese; Other). Children were considered to be members of a racialized group if their parent reported a population group other than ‘White’.

The responding parent’s employment status was assessed by the questions: ‘Last week, did this person work at a job or business?’ and ‘Last week, did this person have a job from which they were absent?’ Parents were considered employed if they answered ‘yes’ to either question. Parents’ educational attainment was self-reported, and categorized as follows: ‘high school diploma or below’; ‘CEGEPFootnote 14, trade certificate, or other certificate below the bachelor’s level’; or ‘Bachelor’s degree or above’.

Household low income status was based on the annual household income in dollars, before taxes and deductions, reported by parents and dichotomised using the household low-income measure (LIM). These after-tax low-income thresholds were $50,306 for a four-person household, $43,566 for a three-person household, and $35,572 for a two-person household, respectively, in 2019 constant dollars (Statistics Canada, 2021b).

Parents reported the number of times the target child had moved homes since birthFootnote 15; for the present study, this variable was categorized as follows: fewer than 2 moves or 2 or more moves. The presence of a step parent, step sibling, or half sibling in the responding parents’ household was assessed using the household roster. Additionally, parents reported the existence of any siblingsFootnote 16 of the child that were not living in the surveyed household via the question ‘Does this person have any brothers or sisters not already listed and living elsewhere?’ (‘yes’/’no’). Parents also reported if the child had experienced the death of a parent or sibling (‘yes’/’no’).

3.2.3 Child Mental Health and Functional Difficulty Indicators

We examine four indicators of children’s mental health and functional difficulties: general mental health, behaviour problems, anxiety, and depression.

Parents of children aged 1–17 reported on their child’s general mental health (‘In general, how is this child’s mental health?’ with responses: ‘excellent’, ‘very good’, ‘good’, ‘fair’, ‘poor’). The majority of parents (55%) indicated their child had ‘excellent’ mental health; very few parents indicated their child had ‘poor’ (< 1%) or ‘fair’ (3%) mental health. For the present study, this variable was dichotomized (excellent/very good vs. good/fair/poor).Footnote 17

Indicators for behaviour problems, anxiety, and depression were assessed using questions from the Washington Group/UNICEF Child Functioning Module. This module was designed to assess child functioning and disability and has been validated for use in many languages and countries (Loeb et al., 2017).

Parents reported on child behaviour problems for children age 2–4 (‘Compared with children of the same age, how much does this child kick, bite, or hit other children or adults?’ with responses: ‘not at all’, ‘the same or less’, ‘more’, ‘a lot more’) and children age 5–17 (‘Compared with children of the same age, does this child have difficulty controlling their behaviour?’, with responses: ‘no difficulty’, ‘some difficulty’, ‘a lot of difficulty’, ‘cannot do at all’). Younger children who used physical violence ‘a lot more’ than peers were considered to have a functional difficulty controlling behaviour. Older children whose parents reported their child had a lot of difficulty controlling behaviour or that they could not control behaviour at all were considered to have a functional difficulty in this domain.

Parents of children ages 5–17 additionally reported on children’s symptoms of anxiety (‘How often does this child appear anxious, nervous, or worried?’) and depression (‘How often does this child seem very sad or depressed?’), with response options ‘never’, ‘a few times a year’, ‘monthly’, ‘weekly’, and ‘daily’. Children who experienced a symptom ‘daily’ were considered to have a functional difficulty in this domain.

3.3 Method of Analysis

Frequency tables were used to describe the proportion of children aged 1–17 in 2019 who had experienced parental separation or divorce. Among those who had experienced a separation or divorce, proportions having each type of contact arrangement (equal; regular; irregular; remote only; none) were tabulated in a second set of frequency tables.

For the full analytical sample of children, logistic regression models were used to predict children’s mental health and functional difficulties from the experience of parental breakup. For the subsample of children who had experienced parental separation or divorce, additional logistic regression models were used to predict mental health difficulties from the type of contact with the other parent. A second set of regressions included all sociodemographic and socioeconomic covariates of interest. Cases with missing data on predictors, outcomes, or covariates were deleted from the regression sample. To account for the complex survey design, all analyses were weighted using survey weights and replicate weights with 1000 bootstrap resamples were used for variance estimation, as per Statistics Canada guidelines (Statistics Canada, 2015). Analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4.

4 Results

4.1 Prevalence and Correlates of Parental Separation or Divorce

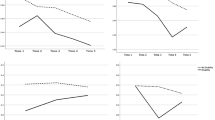

Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1 according to the child’s experience of parental separation or divorce. Overall, 18% of children in Canada (approximately 1,185,700 children) aged 1–17 in 2019 had experienced parental separation or divorce. Figure 1 plots the proportion of children who had experienced parental breakup in their lifetime by age of child. Given the additional years of exposure to the risk of experiencing the event, there is a strong positive correlation between age of children and the proportion who had experienced the breakup of their parents. While 4% of 1 year-olds have experienced parental separation or divorce since birth, this was the case for more than a quarter (26%) of 17 year-olds.

Within Canada, children who had experienced parental separation or divorce were more likely to be living in Nova Scotia, New Brunswick or Quebec, and less likely to be living in Ontario, Manitoba, or Alberta, compared to their counterparts who had not experienced parental breakup. Children with Indigenous identity were found to represent 9% of all children who had experienced parental breakup compared to 4% of children who had not.

Substantial differences in the prevalence of parental separation or divorce were also found according to children’s ethnocultural characteristics. Children belonging to a racialized group or those with an immigrant responding parent were underrepresented in this experience. For example, children with an immigrant responding parent accounted for 38% of children who had not experienced parental breakup, but 21% of children who had experienced the separation or divorce of their parents.

Lower socioeconomic status, as indicated by the responding parent’s low educational attainment and household low-income status, was correlated with the experience of parental separation or divorce. Close to half (46%) of children who had experienced parental breakup were living in a low-income household, compared to 26% of other children.

Clear differences emerged in the level of family complexity according to the child’s experience of parental separation of divorce. One in five children who had experienced parental breakup were currently living with a step parent in the responding household (20%), while this was the case for 1% of other children; presumably, the latter group includes situations where the child’s other biological parent was never part of the child’s life. Half siblings were found to be a common feature in the homes of children who had experienced parental separation or divorce (1 in 6 had at least one half sibling) while step siblings were rarer (5%). Children who had experienced parental breakup were more than three times as likely to have one or more siblings living elsewhere (37% compared to 12% of other children) and were more than twice as likely to have moved households at least twice since birth (61% compared to 28% of other children). Lastly, while 3% of children in Canada had experienced the death of a parent or sibling, this experience was slightly more prevalent among children who had experienced parental separation or divorce (5%).

The proportion of children who had mental health and functional difficulties was significantly higher among the group children who had experienced parental separation or divorce compared to their counterparts who had not. Among children that had experienced parental breakup, 31% had poorer parent-rated mental health, more than twice the rate among other children (14%). The proportions of children with functional difficulties related to anxiety, depression, and behaviour were also approximately twice as high for the population of children who had experienced parental separation or divorce.

4.2 Parenting Time Arrangements

Table 2 further describes the subsample of children who had experienced parental separation or divorce according to the type of contact they had with their other parent. In 2019, the majority (73%) of these children spent some time at the home of the other parent: 21% lived equally with both parents, 36% had regular visits with the other parent, and 17% had irregular visits. An additional 19% of children had no contact with the other parent, while 8% had remote contact only.

As compared with children who lived equally with both parents, children who had regular contact with the other parent were comparatively younger; in contrast, those who had irregular contact, remote contact only or no contact with the other parent were comparatively older. Generally, children who had parenting time arrangements other than equal contact were relatively more likely to be living in a low-income household, less likely to have a responding parent with a Bachelor’s degree or higher, and less likely to have an employed responding parent. Girls were found to be slightly overrepresented in the remote-contact only group (56%). Indigenous children were significantly overrepresented among the irregular contact (12%) and no contact (9%) groups compared to the equal-contact reference group (5%). Equal parenting time arrangements appear to be more prominent in Quebec and less so in Ontario.

Significant ethnocultural differences were found according to the various types of contact children had with the other parent. Children belonging to a racialized group were substantially overrepresented among ‘no contact’ (33%) and ‘remote contact only’ (28%) groups compared to the ‘equal contact’ group (7%). Similar patterns occurred for children with an immigrant responding parent, who represented 40% of all children who had remote contact only with their other parent and 11% of children who lived equally with both parents.

Children with a half sibling—regardless of whether that half sibling lived in the surveyed household or elsewhere—were generally overrepresented among other parenting time arrangements in comparison with the equal contact reference group. Children who had moved households at least twice since birth were significantly overrepresented among irregular contact and remote contact only groups.

We encountered some sample size limitations in the estimation of depression, anxiety, and behavioural difficulties according to type of contact. Nonetheless, the broad pattern of results suggests that children who had equal parenting time arrangements were less likely to have parent-reported mental health or functional difficulties than children who had irregular visits, remote contact only or no contact with the other parent. For instance, 24% of children with equal contact had relatively poor parent-reported general mental health (i.e., poor, fair or good compared to very good or excellent) while this was the case for 40% of children who had irregular visits and 30% of children who had remote contact only or no contact with the other parent. Across all mental health and functional difficulty indicators, children who had irregular contact with the other parent recorded the highest incidence of difficulty.

4.3 Parenting Time Arrangements, General Mental Health, and Functional Difficulties

The results of logistic regression models (unadjusted and adjusted) predicting child mental health and functional difficulties according to the child’s experience of parental separation or divorce are presented in Table 3. The experience of parental breakup was associated with relatively higher odds of having poorer general mental health or functional difficulties.

Odds ratios are substantially lower in the fully adjusted models, indicating that the differences observed in the frequency analysis (Tables 1 and 2) between children who had experienced parental separation or divorce and those that had not are in no small part a result of observed compositional differences between the two groups. Nonetheless, even after accounting for numerous family and child characteristics, there remains a significant association between the experience of parental separation or divorce and poorer mental health or functional difficulties. Given the cross-sectional nature of the measures, this association may reflect a spurious link between parental breakup and other unobserved characteristics, a real effect of the event of parental breakup, or a mixture of these factors.

In fully adjusted models, children who had experienced parental separation or divorce had 1.8 times the odds of poorer general mental health, 1.3 times the odds of having symptoms of anxiety, and 1.4 times the odds of having difficulty controlling behaviour compared to children who had not experienced a separation or divorce. Due to the relatively low incidence of symptoms of depression in the child population generally, fewer significant estimates were found with respect to this outcome. However, the magnitude and direction of estimates generally follow those of the other three mental health and functional difficulties.

In line with previous research (see Merikangas et al., 2009 for a review), older children were more likely than their younger counterparts to experience anxiety, depression, and poorer general mental health than younger children, while females were significantly more likely to experience anxiety and significantly less likely to experience behavioural difficulty. Residence in the province of Quebec also proved to be a consistently significant predictor, associated with lower odds of children experiencing poorer general mental health, depression and anxiety, but increased odds of experiencing behaviour difficulties.

Indigenous children had 1.4 times higher odds of poorer general mental health, a finding consistent with previous research (Lopez-Carmen et al., 2019). As noted by Hwang et al. (2008) and Gopalkrishnan (2018), cultural differences may influence the way people view and assess mental health.

Parental immigrant status was associated with lower likelihood of children experiencing any of the four indicators of mental health and behavioural difficulty by approximately half. Racialized group status was associated with lower likelihood of the child experiencing anxiety or behavioural difficulties.

Higher socioeconomic status—whether measured through the responding parent’s educational attainment, employment status or household low-income status—was associated with lower odds of the child having poorer reported general mental health.

By default, indicators of children’s family complexity and stability of living arrangements are highly correlated with the experience of parental breakup. Nevertheless, even after controlling for the child’s experience of parental separation or divorce these indicators were linked with child well-being. Contrasting effects emerged with respect to the presence of stepfamily members in the household: having a step parent present in the household was associated with reduced odds of poorer general mental health among children, while the presence of step siblings or half siblings was associated with higher relative odds of this outcome. The existence of one or more siblings who lived elsewhere was associated with significantly higher odds of a child experiencing poorer mental health (1.2), depression (1.4), and anxiety (1.3). Children who had moved households at least twice since birth had significantly higher odds of exhibiting poorer general mental health, anxiety and behavioural difficulties. Lastly, children who had experienced the death of a parent or sibling had 1.5 times higher odds of exhibiting poorer general mental health and 2.4 times greater odds of exhibiting depression compared to those that had not.

Results of a second set of logistic regressions are presented in Table 4. In this second series, we limit our subsample to the children who had experienced parental separation or divorce. Once again, we predict poorer general mental health and functional difficulties in depression, anxiety and behaviour, but now according to the parenting time arrangements in place for the child as measured through the type of contact with the other parent.

In comparison with the reference group of children with equal parenting time arrangements, children who had regular visits with the other parent did not have significantly different odds of having poorer general mental health or functional difficulties. In contrast, irregular contact with the other parent was associated with 1.7 times the odds of poorer general mental health, 2.1 times the odds of anxiety, and 2.4 times the odds of behavioural difficulties. Having remote contact only with the other parent was associated with 1.6 times the odds of poorer general mental health and 2.3 times higher odds of anxiety. No significant differences were found between children who had equal contact with both parents versus those who had no contact with their other parent with respect to mental health and functional difficulties, with one exception: children who had no contact with the other parent had 1.9 times higher odds of exhibiting anxiety than children who lived equally with both parents.

Other covariates in the adjusted model (i.e., after controlling for the characteristics of the child and their family) performed similarly to the previous regressions which assessed the significance of the experience of parental breakup during childhood. However, estimates were generally less robust for the model based on the subsample of children who had experienced separation or divorce. This may reflect in part the smaller sample size of the subsample, and/or a truly weaker association between parenting time arrangements and child well-being in comparison with the event of parental breakup itself.

5 Discussion

The goal of this study was to update and improve our understanding of children in Canada who have experienced parental divorce or separation through three interrelated research questions. We first asked: What is the prevalence of the experience of parental separation or divorce in Canada, and what characteristics are associated with this experience? According to the CHSCY, 18% of children aged 1–17 in Canada in 2019 had experienced the breakup of their parents at some point in their childhood to date. The prevalence of this experience generally increased according to the age of the child, reflecting their longer exposure to the risk of this event. Within Canada, considerable diversity was found in the prevalence of this experience depending on the child’s characteristics and those of their family. In line with previous findings, associations were found between the child’s demographic characteristics, the socioeconomic status of the family and the experience of parental breakup. As might be expected, children who had experienced parental breakup had considerably higher levels of family complexity than other children—as indicated by the presence of step parents, step siblings, and half siblings—and less stable living arrangements throughout their childhoods, as measured through the number of residential moves since birth.

Our secondary research question was: What types of parenting time arrangements are most common for children following the breakup of their parents, and is there an association between the type of contact with the other parent and the characteristics of the child and their family? We utilize a relatively nuanced measure which delineates the mode of contact with the other parent (in-person versus remote contact only) as well as its consistency (equal, regular or irregular), as recommended by Baude et al. (2016) and Steinbach and Augustijn (2021). As previous Canadian studies from the perspective of parents have indicated recently (Sinha, 2014; Statistics Canada, 2021a), we find that following parental breakup, the majority of children split their time living at two parental households to some degree. The most common parenting time arrangement was to have regular visits with the other parent (36%). There was, however, considerable heterogeneity in children’s experiences of post-parental breakup living arrangements: children were nearly equally likely to split their time equally with both parents (21%) as to have no contact whatsoever with their other parent (19%).

Echoing the general findings in other countries and those recently made in the Canadian context by Pelletier et al. (2017), we find that children who had equal contact with the other parent were more likely to have higher socioeconomic status as measured through the responding parent’s employment status, educational attainment, or household low-income status. The child’s sociodemographic characteristics also proved to be significantly linked to the parenting time arrangement in place.

Thirdly, we asked: How does the experience of parental separation or divorce, and subsequent parenting time arrangement, impact the likelihood that a child is reported to have poorer general mental health or functional difficulties? In line with previous research (Reiss, 2013; Strohschein, 2005, 2012), we find that children who had previously experienced the breakup of their parents had significantly higher odds of poorer general mental health, anxiety, and behavioural difficulties, even after controlling for numerous characteristics linked to selection and moderation effects in previous literature.

As with studies of other countries (Baude et al., 2016; Bjarnason & Arnarsson, 2011; Nielsen, 2014, 2018, 2021; Steinbach, 2019; Vezzetti, 2021), we find significant differences in the association between type of contact with the other parent and the odds of the child experiencing mental health and functional difficulties. Our study nuances this, however, by distinguishing between the regularity (regular visits, irregular visits, no contact) and the mode (remote only) of contact with the other parent. In comparison with children who lived equally with both parents, those who had irregular visits with the other parent had significantly higher odds of poorer general mental health, anxiety, and behavioural difficulties. Similarly, those children who had remote contact with the other parent had significantly higher odds of poorer general health and anxiety. In contrast, children who had regular visits with the other parent did not experience significantly different odds of poorer general mental health or functional difficulties in comparison with their counterparts who lived equally with both parents. Moreover, in comparison with children who lived equally with both parents, those who had no contact at all with their other parent by and large did not have significantly different odds of experiencing poorer general mental health or functional difficulties (with the exception of anxiety). Taken together these findings indicate that following parental breakup there is not necessarily a straightforward positive correlation between the amount of contact with the other parent and child well-being. Instead, patterns by type of contact support previous assertions in the literature regarding the importance of stability in a child’s living arrangements (Fomby & Cherlin, 2007; Lee & McLanahan, 2015; Waldfogel et al., 2010), as children who had no contact at all with their other parent generally had similar well-being characteristics to those who lived equally with both parents. This notion is further bolstered by the findings that more numerous residential moves, as well the experience of the death of a parent or sibling, were both associated with greater odds of poorer general mental health in children.

In addition to investigating our three principal research questions, this study uncovered several other findings of note. Given the multicultural nature of Canadian society, the diverse interaction of ethnocultural characteristics and the child’s experience of parental breakup is instructive. Children of immigrants and those belonging to a racialized group were decidedly less likely to have experienced parental separation or divorce, but those that did were disproportionately more likely to have either no contact at all or remote contact only with the other parent. To what extent these patterns relate to practical barriers of geographic distance and/or international travel versus cultural mores remains to be studied. After controlling for the experience of parental breakup and other characteristics, children of immigrants had significantly lower odds of experiencing poorer mental health or functional difficulties than other children. This finding echoes those of Beiser et al. (2002) who find that paradoxically, though immigrant children in Canada are more likely than non-immigrant children to be living in poverty, they have also been found to have lower levels of emotional and behavioural difficulties.

In contrast, Indigenous children were significantly overrepresented among the population of children that had experienced the breakup of their parents. Following parental breakup, Indigenous children were more likely than non-Indigenous children to have irregular contact or no contact with the other parent. Compared to non-Indigenous children, Indigenous children also had significantly higher odds of experiencing poorer general mental health and behavioural difficulties. Indigenous children in Canada and worldwide bear a disproportionate burden of mental illness (Young et al., 2017), and have been reported to experience more emotional and behavioural symptoms compared with non-Indigenous peers (Lopez-Carmen et al., 2019).

Children residing in the province of Quebec also appeared to have a distinct experience of the outcomes of interest. Children in Quebec were more likely to experience parental separation or divorce, yet residence in this province was also associated with lower odds of experiencing poorer mental health, depression and anxiety compared to children living in the rest of Canada. Given Quebec’s relatively generous social and family policies and programs (Beaujot et al., 2013), are Quebec children and families less susceptible to the negative socioeconomic associations of the experience of family breakup compared to children in other parts of Canada? Further examination of these patterns, including the possibility of a significant interaction effect between residence in Quebec and parenting time arrangement, is needed.

As suggested by Steinbach (2019), by widening our analytical lens to the larger family ‘constellation’ and household living arrangements, we were able to gain further insights into children’s experience of parental separation or divorce. The specific nature of a child’s family complexity was found to have diverse, multifaceted associations with child well-being, even after controlling for the experience of parental breakup. While the presence of a step parent in the home was associated with lower odds of the child exhibiting poorer general mental health, the presence of a step or half sibling in the household, or the existence of a sibling living elsewhere, were associated with significantly higher odds of this outcome. However, these patterns were largely rendered non-significant after narrowing our analysis to children who had experienced parental breakup, with the exception of the association related to half siblings. The introduction of new family members into the household was also linked to the type of contact with the other parent: among children who had experienced parental breakup, those with a half sibling living in the surveyed household were overrepresented in the ‘no contact’ group. More research is needed to better understand the interaction between the child’s experience of parental separation or divorce, the introduction of new family members into a child’s life, and child well-being. In particular, these findings suggest that the nature of sibling dynamics within stepfamilies may be of particularly salient influence, as has been previously suggested by Thomson and McLanahan (2012).

If updated in future years, the findings of this study could be used support the ‘diverging destinies’ thesis of McLanahan (2004), who argues that various trends associated with the second demographic transition—assortative mating, parental divorce and separation, and non-marital childbearing—have led to growing disparities in children’s resources, including financial resources and access to time with the other parent (primarily fathers) according to the mother’s socioeconomic status. This study found that children in low-income households were significantly overrepresented in the experience of parental separation or divorce; following parental breakup, these children were significantly overrepresented among the groups having no contact, remote contact only, irregular contact, or regular contact with the other parent, as opposed to equal contact. Children in low-income households also had significantly higher odds of poorer general mental health. Patterns were similar with respect to children with lower-educated parents and those with parents who did not engage in paid work. Whether these disparities will widen in the future remains to be seen.

5.1 Limitations

Our study examined parenting time arrangements following parental breakup, but the reality of shared parenting arrangements goes beyond the type of contact with the other parent captured in this study. We were not able to measure the existence and nature of parental agreements with respect to decision-making about various aspects of the child’s life. de Torres Perea (2021) notes that shared parenting ‘involves the provision of ongoing contact by a child with both parents, so that both remain involved in his or her life. It does not necessarily imply a sharing of the child’s overnight stays between the parents.’ The well-being of the parent also appears to be an important factor in children’s experience of shared parenting time (Bjarnason & Arnarsson, 2011; Steinbach, 2019), but we were not able to assess this possibility in our study.

In the analytical sample, the responding parent was female in the vast majority of cases, particularly among the subsample of children that had experienced parental separation or divorce (91%). As noted by Juby et al. (2005), this could create some degree of unmeasured bias in response patterns.

While we were able to capture some key aspects of the complexity of the child’s main residential family (i.e., the presence of step parents, step siblings and half siblings in the home), ideally, we would also incorporate information about the family situation of the other, non-responding parent. Many of the children in our study may in reality have had not one but two or more sets of step parents, step siblings, and/or half siblings, some living in the home of the other parent on a permanent or part-time basis. The ability to identify and measure these complex living arrangements would facilitate the assessment of whether and how to redefine ‘parenthood’ and ‘family’ when children live in multiple familial settings simultaneously and parenthood is in many cases ‘de-coupled’from living arrangements (Strohschein, 2017).

Our measures of the child’s type of contact with the other parent may have held some unmeasured degree of bias related to the imprecision of the source question ‘What type of contact does the child now have with his other parent or guardian?’; the response categories ‘Lives equally with both parents’, ‘regular visits’, and ‘irregular visits’ are not necessarily mutually exclusive; no specific time criteria is attached to the terms (e.g., duration of visit, overnight visits, interval between visits). For those children who had ‘video call or chat, telephone, letter or email contact only’ with the other parent, we do not know the frequency of this remote contact; the impacts of daily video chats versus one phone call per year on the child’s birthday are presumably very different, but not discernible here.

Lastly, our study is limited by the cross-sectional nature of the data source. As noted by the Canadian Paediatric Society (2013), ‘Divorce is a process, not a single event, and so the child’s adjustment occurs in stages’. In order to improve our understanding of the casual mechanisms at work in the relationship between shared parenting time and child well-being, there is a strong need for relevant longitudinal data and analyses. Neither parenting time arrangements nor child well-being are static characteristics; both are likely to evolve as the child ages, among other developments (Steinbach & Augustijn, 2021). Other factors, such as parental conflict and cooperation, are also likely to change as further time passes since the beginning of the separation or divorce (Palmer, 2002). Furthermore, longitudinal studies are necessary in order to capture the situation of children both before and after parental breakup in order to assess the possibility of fixed effects and reverse causality; i.e., that children’s previously existing behavioural issues may lead to a greater risk of parental breakup (Fomby et al., 2021; Strohschein, 2005, 2012).

Indeed, time since separation in and of itself is likely to play an important mediating role in child well-being (Baude et al., 2016). The survey content used in this analysis was limited in this regard by its lack of specificity. The question ‘has this child experienced the separation or divorce of a parent?’ provides no indication of the timing of that event. Furthermore, since this question was used as a filtering criteria for the question regarding type of contact with the other parent, we were unable to assess the parenting arrangements and well-being of children whose parents never lived together (and therefore never separated or divorced); this remains a key gap in the literature (Steinbach, 2019).

Overall, our study found that children who had experienced parental separation or divorce in childhood exhibited higher odds of having mental health or functional difficulties. However, we also found that the experience of parental separation or divorce and subsequent parenting time arrangements is highly heterogeneous among children in Canada. Policies and programs directed at children with separated or divorced parents should take into account the potential diversity of experiences depending on children’s sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics.

Data Availability

The data are available in Statistics Canada Research Data Centres and accessible to those with approved projects. See https://crdcn.org/research to make an application.

The SAS programs used to compute estimates are available from the authors upon request.

Notes

In this article, the “other parent” refers to the child’s other parent or guardian who is not a member of the surveyed household.

Status as of the time of submission of this article. Statistics Canada has recently undertaken a pilot project to produce key indicators of annual divorce flows for Canada, provinces and territories.

The share of couples that were common law in Canada increased from 5.6% in 1981 (Statistics Canada, 2012) to 21.3% in 2016 (Statistics Canada, 2017b).

The census does not collect information on whether an individual has separated from a common-law union.

In addition to the fact that divorces represent only a fraction of all parental breakups, an increasing share of ex-spouses utilize informal parenting arrangements (Sinha, 2014). The Department of Justice Canada’s Survey of Family Courts collects partial data on custodial outcomes, only from Divorce files, and only from a limited number of courts. Statistics Canada’s Civil Court Survey collects information on the nature of judgments in civil court related to legal custody decisions and physical custody decisions; the survey does not yet have full coverage of all jurisdictions.

As described by Sinha (2014): ‘Generally speaking, parenting plans identify the living arrangements of the child, the time each parent spends with the child, and the decision-making responsibilities of parents on matters such as schooling, religion and medical care. It may be an informal arrangement, or one that is formalized in writing in an arrangement or court order, either by the parents themselves or through a lawyer, family justice service or a judge’.

This arrangement is often referred to in the literature as ‘shared custody’ or ‘joint custody’. Canada is currently in a period of substantial transition with respect to legal terminology related to this topic. Following amendments in 2021 to the Divorce Act, terms such as ‘joint physical custody’ and ‘access’ are no longer used by the Department of Justice Canada (Department of Justice Canada, 2021a). Instead, the term ‘shared parenting time’ is suggested (Department of Justice Canada, 2021b); thus, we use this term in the present article. That said, this term does not always lend itself well to studies such as this one in which the unit of analysis is the child. Pelletier (2017) utilizes the term ‘dual residence’, which clearly indicates the unit of the analysis is the child and that the outcome of interest is the child’s residential situation; however, there is a risk that this term could be mistaken by a general audience as referring to the holding of residence permits in two countries.

The most recent 2017 GSS Family cycle collected information on parenting time among separated or divorced persons with at least one dependent child according to various measures with respect to the reference period, the experience being asked about, and the frequency of that experience (Statistics Canada, n.d.). For the purposes of determining eligibility for the Canada Child Benefit, the Canada Revenue Agency asks tax-filers to indicate whether a child lives ‘about equally between both parents’, ‘mostly with you’, or ‘mostly with the other parent’, with no further specification (Canada Revenue Agency, n.d). The demarcation of what cut point, in terms of the proportion of the child’s time spent living with each parent, should be used to demarcate shared parenting appears to be undecided in the international literature, ranging anywhere from 25% (Steinbach, 2019), 30% (Baude et al., 2016) or 30 to 35% (Kline Pruett & DiFonzo, 2014), while in Canada, 40% is the criterion utilized in federal courts when establishing child support payments (Department of Justice Canada, 2021b).

As announced in Finance Canada’s 2018 Budget (Department of Finance Canada, 2018). The province of Quebec has had dedicated second parent leave since 2006.

From the initial frame of the Canada Child Benefit, initial weights are calculated for each sampled child. These weights undergo several adjustments, including for non-response and calibration to known population totals, to create the final weights. For more information on the collection process, response rate evaluation, and processing procedures of the CHSCY, see https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=5233#a3

Foster children are in theory excluded from the sample because the sampling frame is the Canada Child Benefit (CC) file; foster families do not receive the CCB. However, relationship possibilities within the household nonetheless include ‘foster parent’ in cases that the selected child is residing in a foster home at the time the survey is sent (and the foster family was forwarded the survey invitation). Given that the filtering criteria (i.e., the survey question ‘has this child experienced the separation or divorce of a parent?’) do not specify the adoptive/biological nature of the parent–child relationship, it was decided to remove adopted children from the analysis of type of contact with the other parent. Since it was not possible to distinguish children who had experienced the death of a parent (which would influence type of contact with said parent) versus the death of a sibling (which would not), these children were removed from the analytical subsample examining type of contact.

Rural areas were defined based on population concentration and density per square kilometre, and proximity to core areas (Statistics Canada, 2020b).

On November 27, 2006, the House of Commons in Ottawa adopted a motion on recognition of the Quebec nation ‘That this House recognize that the Québécois form a nation within a united Canada’. In 2014, the Supreme Court of Canada referred to the existence of ‘Quebec’s distinct legal traditions and social values’. Reference re Supreme Court Act, ss. 5 and 6, 2014 SCC 21, para. 49. https://www.sqrc.gouv.qc.ca/relations-canadiennes/institutions-constitution/statut-qc/reconnaisance-nation-en.asp

Collège d’enseignement général et professionnel (Quebec only).

The responding parent was instructed to exclude visits to the other parents’ household in the context of shared parenting time.

No distinction is specified with respect to whether the siblings are biological, adopted, half of step.

Sensitivity analyses tested an alternative dichotomization of ‘excellent/very good/good’ vs. ‘fair/poor’. Regression coefficients were similar to the ultimate derived variable but were less robust likely owing to the significantly smaller number of cases.

References

Bala, N., Birnbaum, R., Poitras, K., Sain, M., Cyr, F., & LeClair, S. (2017). Shared parenting in Canada: Increasing use but continued controversy. Family Court Review, 55(4), 513–530.

Baude, A., Pearson, J., & Drapeau, S. (2016). Child adjustment in joint physical custody versus sole custody: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 57(5), 338–360.

Beaujot, R., Du Jiangqin, C., & Ravanera, Z. (2013). Family policies in Quebec and the rest of Canada: Implications for fertility, child-care, women’s paid work, and child development indicators. Canadian Public Policy, 39(2), 221–239.

Beiser, M., Hou, F., Hyman, I., & Tousignant, M. (2002). Poverty, family process, and the mental health of immigrant children in Canada. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 220–227.

Bérard-Chagnon, J., Laflamme, N., & Ménard, F-P. (n.d.). (external publication forthcoming). Examining the consistency of de facto marital status between tax data and the 2016 Census. Statistics Canada internal report (unpublished)

Bjarnason, T., & Arnarsson, A. M. (2011). Joint physical custody and communication with parents: A cross-national study of children in 36 western countries. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 42(6), 871–890.

Bohnert, N., Milan, A., & Lathe, H. (2014). Enduring diversity: Living arrangements of children in Canada over 100 years of the census. Demographic Documents, Statistics Canada catalogue no. 91F0015M–No. 11.

Braver, S.K., & Votruba, A.M. (2021). Does joint physical custody “cause” children’s better outcomes? In J.M. de Torres Perea, E. Kruk & M. Ortiz-Tallo (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of shared parenting and best interest of the child (pp. 63–77). Imprint Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003140566

Canadian Paediatric Society (2013). Position statement: Supporting the mental health of children and youth of separating parents https://cps.ca/en/documents/position/%20mental-health-children-and-youth-of-separating-parents

Canada Revenue Agency (no date). Canada child benefit: Who can apply.https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/child-family-benefits/canada-child-benefit-overview/canada-child-benefit-before-you-apply.html#primary

Corak, M. (2001). Death and divorce: The long-term consequences of parental loss on adolescents. Journal of Labor Economics, 19(3), 682–715.

Coulter, R., van Ham, M., & Findlay, A. M. (2016). Re-thinking residential mobility: Linking lives through time and space. Progress in Human Geography, 40(3), 352–374.

Department of Finance Canada (2018). Budget plan: Equality + growth: A strong middle class. February 27, 2018. https://www.budget.gc.ca/2018/docs/plan/toc-tdm-en.html

Department of Justice Canada (2021a). The Divorce Act changes explained http://bit.ly/3nG5Up0

Department of Justice Canada (2021b). “Section 4: What is the best parenting arrangement for my child?” Making plans: A guide to parenting arrangements after separation or divorce. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/fl-df/parent/mp-fdp/p5.html

de Torres Perea, J.M. (2021). Recent developments in shared parenting in western countries. In J.M. de Torres Perea, E. Kruk & M. Ortiz-Tallo (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of shared parenting and best interest of the child (pp. 355–369). Imprint Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003140566

Ferrer, A., & Pan, Y. (2020). Divorce, remarriage and child cognitive outcomes: Evidence from Canadian longitudinal data of children. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 61(8), 636–662.

Fomby, P., & Cherlin, A. J. (2007). Family instability and child well-being. American Sociological Review, 72(2), 181–204.

Fomby, P., Ophir, A., & Carlson, M. J. (2021). Family complexity and children’s behavior problems over two U.S. cohorts. Journal of Marriage and Family, 83, 340–357.

Fostik, A., & Le Bourdais, C. (2020). Regional variations in multiple-partner fertility in Canada. Canadian Studies in Population, 47(1), 73–95.

Gopalkrishnan, N. (2018). Cultural diversity and mental health: Considerations for policy and practice. Frontiers in Public Health, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00179

Hwang, W.-C., Myers, H. F., Abe-Kim, J., & Ting, J. Y. (2008). A conceptual paradigm for understanding culture’s impact on mental health: The cultural influences on mental health (CIMH) model. Clinical Psychology Review, 28(2), 211–227.

Juby, H., Marcil-Gratton, N., & Le Bourdais, C. (2004). When parents separate: Further findings from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth. Department of Justice Canada Research Report 2004-FCY-6E 2004.

Juby, H., Le Bourdais, C., & Marcil-Gratton, N. (2005). Sharing roles, sharing custody? Couples’ characteristics and children’s living arrangements at separation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 157–172.

Kitterod, R., & Lyngstad, J. (2012). Untraditional caring arrangements among parents living apart: the case of Norway. Demographic Research, 27(5), 121–152.

Kline Pruett, M., & DiFonzo, J. H. (2014). Closing the gap: Research, policy, practice and shared parenting. Family Court Review, 52(152), 152–174.

Kline Pruett, M., McIntosh, J. E., & Kelly, J. B. (2014). Parental separation and overnight care of young children, part 1: Consensus through theoretical and empirical integration. Family Court Review, 52(2), 241–256.

Koster, T., & Castro-Martin, T. (2021). Are separated fathers less or more involved in childrearing than partnered fathers? European Journal of Population, 37, 933–957.

Koster, T., Poortman, A.-R., van der Lippe, T., & Kleingeld, P. (2021). Parenting in postdivorce families: the influence of residence, repartnering, and gender. Journal of Marriage and Family, 83(2), 498–515.

Laplante, B. (2016). A matter of norms: Family background, religion, and generational change in the diffusion of first union breakdown among French-speaking Quebeckers. Demographic Research, 35(27), 785–812.

Lee, D., & McLanahan, S. (2015). Family structure transitions and child development: Instability, selection and population heterogeneity. American Sociological Review, 80(4), 738–763.

Lesthaeghe, R. (2020). The second demographic transition, 1986–2020: Sub-replacement fertility and rising cohabitation – a global update. Journal of Population Sciences 76(10). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41118-020-00077-4

Letablier, M.T., & Wall, K. (2018). Changing lone parenthood patterns: New challenges for policy and research. In L. Bernardi & D. Mortelmans (Eds.), Lone parenthood in the life course. Life Course Research and Social Policise, vol 8. Spring, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-63295-7_2

Loeb, M., Cappa, C., Crialesi, R., & de Palma, E. (2017). Measuring child functioning: the Unicef/Washington Group Module. Salud Publica de México, 59(4). https://doi.org/10.21149/8962

Lopez-Carmen, V., McCalman, J., Benveniste, T., Askew, D., Spurling, G., Langham, E., & Bainbridge, R. (2019). Working together to improve the mental health of Indigenous children: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review, 104, 104408.

Lopez Narbona, A.M., Moreno Minguez, A., & Ortega Gaspar, M. (2021). Family structure, parental practices and child wellbeing in postdivorce situations. In J.M. de Torres Perea, E. Kruk & M. Ortiz-Tallo (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of shared parenting and best interest of the child (pp 170–182). Imprint Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003140566

Mandemakers, J. J., & Kalmijn, M. (2014). Do mother’s and father’s education condition the impact of parental divorce on child well-being? Social Science Research, 44, 187–199.

Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2000). ‘Swapping’ families: Serial parenting and economic support for children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(1), 111–122.

Marcil-Gratton, N., & Le Bourdais, C. (1999). Custody, access and child support: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Children and Youth. Department of Justice Canada.

Margolis, R., Choi, Y., Hou, F., & Haan, M. (2019). Capturing trends in Canadian divorce in an era without vital statistics. Demographic Research, 41(52), 1453–1478.

McLanahan, S. (2004). Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41, 607–627.

McLanahan, S., & Jacobsen, W. (2015). Diverging destinies revisited. In P.R. Amato et al. (eds.), Families in an era of increasing inequality (pp 3–23), National Symposium on Family Issues 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08308-7_1

Merikangas, K. R., Nakamura, E. F., & Kessler, R. C. (2009). Epidemiology of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 11, 7–20.

Nielsen, L. (2014). Shared physical custody: Summary of 40 studies on outcomes for children. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 55, 614–636.

Nielsen, L. (2018). Joint versus sole physical custody: Children’s outcomes independent of parent-child relationships, income and conflict in 60 studies. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 59(4), 247–281.

Nielsen, L. (2021). Joint versus sole physical custody: Which is best for children? In J.M. de Torres Perea, E. Kruk & M. Ortiz-Tallo (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of shared parenting and best interest of the child (pp 40–50). Imprint Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003140566

Palmer, S. E. (2002). Custody and access issues with children whose parents are separated or divorced. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 4(Suppl), 25–38.

Pelletier, D. (2016). The diffusion of cohabitation and children’s risks of family dissolution in Canada. Demographic Research, 35(45), 1317–1342.