Abstract

The Mediterranean basin harbours a vast number of plant species, many of which are endemic and hold various traditional uses for food purposes. Calabria is one of the Italian regions partially studied from an ethnobotanical point of view. The objective of this work is to provide an overview of the food uses of plants known up to now in Calabria. We considered 9 published papers and 11 unpublished sources from field interviews. The data collected were entered into a Microsoft Access® database. The RFC and CI indices were then calculated for quantitative analysis. We collected a total of 1727 records related to 296 taxa, of which 39 subspecies, from 70 botanical families. The most frequently cited families were Asteraceae with 60 taxa (20.2%, 402 records), followed by Rosaceae (27, 9.1%, 203 records). The taxa with the higher RFC are Borago officinalis (RFC: 0.80), Cichorium intybus (0.70), and Portulaca oleracea (0.65); regarding the CI the highest values were found for Borago officinalis (CI: 3), Rubus ulmifolius (2.20) and Asparagus acutifolius (2.10).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The ongoing climate change and its consequences on agro-ecosystems require greater attention on the plant species useful for food purposes (Semeraro et al. 2023): these species can represent an important genetic resource strategically utilized also to draw upon ancient knowledge for the development of new agriculture and to envision the future of the next generations (Jensen and Pliscoff 2023; Perrino and Perrino 2020). This involves the creation of a new economic strategy at the local level (Lovrić et al. 2023). For this reason, the recovery of ethnobotanical knowledge in territories all over the world still plays an important role in building a sustainable future with a decreasing impact on the planet (Estrada-Castillón et al. 2022; Zocchi et al. 2022; Mongalo and Raletsena 2023). This becomes particularly relevant considering the continuous increase in the world population (Hadush et al. 2019).

The Mediterranean basin harbours a remarkable richness of plant species (Comes 2004; Musarella et al. 2020), many of which are endemic (Caruso 2022), and hold various traditional uses for food purposes (Camarda et al. 2017; Baydoun et al. 2023; Laface et al. 2023). Italian regions boast an enormous number of ethnobotanically important species, the knowledge of which has been highlighted by various ethnobotanical studies in recent years (Pasta et al. 2020; Monari et al. 2022; Motti et al. 2022; Lombardi et al. 2023). Calabria is one of the Italian regions richest in species, including many endemism (Bernardo 2000; Spampinato 2014): however, it has only been partially studied from an ethnobotanical point of view, considering several aspects of food and medical purposes (i.e.Nebel et al. 2006; Passalacqua et al. 2006; Mattalia et al. 2020a, b).

The objective of this work is to provide an overview of the food uses of plants known up to now in Calabria. This study is aimed to determine whether the studies conducted so far are sufficient or if there is a need to initiate new ones. Additionally, it aims to uncover the potential implications for the development of a new, local, and more sustainable economy.

Materials and methods

Study area

Calabria is a region in southern Italy known for its rich biodiversity and unique cultural history (Marziliano et al. 2016; Mattalia et al. 2020a; Cantasano et al. 2021).

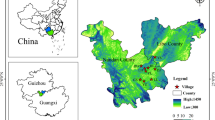

The Calabria region, with an area of 15,080 km2, is located in the central Mediterranean Sea and stretches approximately 250 kilometres from north to south (Fig. 1). It is bordered by the Ionian Sea to the south and east, the Tyrrhenian Sea to the west and Basilicata region to the north. Most of Calabrian territory is mountainous, with two parts of the Apennine chain occupying almost all of its land mass (Barbaro et al. 2022).

According to the classification of Rivas-Martínez et al. (2002), also taken up by other authors (Spampinato 2014), the climate of the Calabria region is classified as Mediterranean, with considerable mesoclimatic variations influenced by altitude, topography and position in relation to the sea.

This region is a fascinating place to conduct research that is related to ancient local cultures and involves the study of traditional knowledge of plants, their names and uses by local communities (Spampinato et al. 2017, 2022).

Ethnobotanical surveys and data analysis

We considered and analysed 9 published works and 11 unpublished sources from field interviews. The published data were obtained from online platforms such as Google Scholar and Scopus and cover the period 2006 to 2022. The unpublished data were collected through semi-structured interviews that follow the model of Musarella et al. (2019) conducted between 2012 and 2020. These sources are related to the ethnobotanical knowledge of the Calabria region, focusing on wild and cultivated plants used for food based on local traditions across different parts of the region. The collected data was entered into a Microsoft Access® database having the same structure as the paper interview sheet. All the recorded information encompassed, among others: type of use, purpose, plant organs, origin, chorology, life form, method of preparation, and method of conservation. The life forms of the taxa follow the classification of Raunkiaer (1934), instead, the chorological type is according to Pignatti (1982). Scientific nomenclature follows the second edition of “Flora d’Italia” (Pignatti et al. 2017a, 2017b, 2018, 2019). For all the taxa, we calculated quantitative indices to highlight their ethnobotanical value: the Frequency of Citation (FC), a basic value in according to Tardío and Pardo-de-Santayana (2008), that indicates the number of informants mentioning a species, Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC), in according to Tardío and Pardo-de-Santayana (2008), which is used to calculate the frequency with which a taxon is cited by informants in relation to the total number of informants and has a value between 0 and 1, and Citation Index (CI) in according to Monari et al. (2022) that indicate the value of the taxa based by the number of citations.

Results and discussion

We collected a total of 1726 records related to 296 taxa, of which 39 subspecies, from 70 botanical families (Table 1 in Online Resource 1). The list of the botanical families with the number of citations and the taxa of each family are given in Online Resource 2 (Table 2).

The most frequently cited families were Asteraceae (60 taxa, 20.2%, 402 records), followed by Rosaceae (27 taxa, 9.1%, 203 records), Brassicaceae (25 taxa, 8.4%, 133 records), and Asparagaceae (7 taxa, 2.4%, 101 records). Not surprisingly, the Asteraceae is the family with the highest number of taxa recorded in Calabria: in fact, this family is the most abundant in the region in terms of number of taxa, like in the whole Italy (Bartolucci et al. 2024; Galasso et al. 2024) and in the world (Cano et al. 2019).

In total, we recorded 296 taxa of food interest. The list of all taxa is shown in Online Resource 1 (Table 1) together with the quantitative indices. The taxa with the higher RFC are Borago officinalis L. (RFC: 0.80), Cichorium intybus L. (0.70), Portulaca oleracea L. (0.70), Asparagus acutifolius L. (0.60), Sambucus nigra L. (0.60), Ficus carica L. (0.50), Hypochaeris radicata L. (0.50) and Rubus ulmifolius Schott (0.50). Regarding the CI, the highest values were found for Borago officinalis (CI: 3), Rubus ulmifolius (2.20), Asparagus acutifolius (2.10), Cichorium intybus (2.10), Ficus carica (2.05), Taraxacum sp.pl. (2), Clematis vitalba L. (1.80) and Muscari comosum (L.) Mill. (1.60). With the most citations (60), the highest RFC and CI values and the largest number of food uses (12), B. officinalis is the most relevant taxon.

The most common life forms of the recorded taxa are Hemicryptophytes (37%), followed by Therophytes (27%) and Phanerophytes (27%) (Fig. 2).

Regarding the chorological types (Fig. 3), the most relevant are Stenomediterranean (24%), Cosmopolitan (24%) and Eurasiatic (23%).

Another interesting information from this study was the part of the plant consumed by the informants. Figure 4 shows that the parts of the plant most commonly used as a food are the leaves (with 519 citations) followed by fruits (422) and aerial parts (226).

Within the food purposes, subcategories have been established to clearly distinguish the intended use of each plant species. Figure 5 presents the most prevalent purposes.

In general, the taxa with the highest number of reported uses belongs to the "side dishes" subcategory (encompassing 134 taxa mentioned in 436 interviews), followed by “snacks” (with 74 taxa mentioned in 248 interviews) and “salads” (with 107 taxa mentioned in 209 interviews).

Side dishes

The category of side dishes includes all those preparations in which the plants, mostly the leaves, basal rosettes and aerial parts, are cooked in a pan with the addition of salt, oil, garlic and sometimes even breadcrumbs. It is a poor and ancient dish, typical of the Mediterranean area, which has remained constant despite globalization (Helstosky 2009; Kremezi 2000; Renna et al. 2015). The most commonly used taxon for this type of use was Borago officinalis with 26 citations (Fig. 6).

There are several data available worldwide regarding B. officinalis for this purpose, especially in Italy (Nebel et al 2006; Passalacqua et al. 2006; Bellusci 2017; Mattalia et al. 2020b; Gentile et al. 2022 (Calabria); Pieroni and Cattero 2019 (Puglia); Guarrera et al. 2006 (Basilicata); Menale et al. 2006 (Molise); Ardenghi et al. 2017 (Piemonte and Lombardia); Cornara et al. 2009 (Liguria); Lentini and Venza 2007; Licata et al. 2016 (Sicily); Lucchetti et al. 2019 (Marche); Uncini Manganelli et al. 2002; Signorini et al. 2008 (Toscana)) and in Spain (Tardío et al. 2006; Aceituno Mata 2010).

The second most recurrent taxon is Cichorium intybus (25 citations) (Fig. 6); its use as a side dish is very common in Calabria: in fact, many scientific works confirm its use in different parts of Calabria (Bernardo 2000; Nebel et al. 2006; Bellusci 2017; Mattalia 2020b; Gentile et al. 2022). In the regions bordering Calabria, such as Basilicata, this species is also commonly used for side dish (Pieroni and Quave 2005; Sansanelli et al. 2017). This species is also used in other Italian regions: Liguria (Cornara et al. 2009), Puglia (Pieroni and Cattero 2019), Sardegna (Signorini et al. 2009), Sicilia (Licata et al. 2016), Toscana (Signorini et al. 2008) and Umbria (Uncini Manganelli et al. 2002; Ranfa and Bodesmo 2017). Regarding other countries, the same use was recorded in Spain (Tardío et al. 2006, Aceituno Mata 2010; Morales et al. 2011) and Lebanon (Baydoun et al. 2017).

Anethum piperitum Ucria (17 citations) is also used for side dishes purpose. This use is commonly known in Italy: Calabria (Nebel et al. 2006; Patti et al. 2024), Sicilia (Licata et al. 2016), Sardegna (Signorini et al. 2009) and Toscana (Signorini et al. 2008). Further data regarding its use was found in Spain (Aceituno Mata 2010).

Snacks

The "snacks" category encompasses all species that are consumed raw without any prior preparation. Typically, these consist of fruits which are often plucked straight from the plant and directly consumed. The taxon most frequently found in this category is Ficus carica with 22 citations (Fig. 7).

The use of F. carica fruits as snacks is well-known both in Italy and abroad. Within the Graecanic area (Southern Italy), F. carica fruits are used as snacks both fresh and dried: the fruits are dried and then eaten in winter and are called ‘còzsula’ in dialect (Nebel et al. 2006). In Italy, its fruits are also consumed in Liguria (Cornara et al. 2009), Basilicata (Sansanelli et al. 2017), Marche (Lucchetti et al. 2019) and Toscana (Uncini Manganelli et al. 2002). The same use has also been found in Spain (Aceituno Mata 2010), Lebanon (Baydoun et al. 2017) and Pakistan (Khan et al. 2021).

The second taxon commonly used as a snacks is Juglans regia L., whose kernels, or nuts, are eaten. In Calabria, there are numerous reported uses (Passalacqua et al. 2006; Siviglia 2011; Lupia and Lupia 2013; Mattalia et al. 2020a); in addition, some studies have reported the specific use of nuts together with F. carica to produce a snack called 'stuffed figs' (Nebel et al. 2006; Mattalia 2020b).

Juglans regia is consumed as a snack in Marche (Lucchetti et al. 2019) and Lombardia (Vitalini et al. 2015). Moreover, Vitalini et al. (2015) describe it as an energizing snack. This species is consumed as a snack also in Spain (Aceituno Mata 2010; Rigat et al. 2016).

Rubus ulmifolius (13 citations) (Fig. 7) is known in Calabria for producing exceptionally sweet fruits that are picked and consumed directly from the tree, a characteristic that has been well documented in the scientific literature (Nebel et al. 2006; Mattalia et al. 2020b; Gentile et al. 2022). Furthermore, R. ulmifolius is also utilized in other regions of Italy such as Basilicata (Sansanelli et al. 2017), Sicilia (Tavilla et al. 2022), Sardegna (Signorini et al. 2009) and Marche (Lucchetti et al. 2019). In Toscana, Signorini et al. (2008) reported that the young shoots of R. ulmifolius can be peeled and consumed raw, like the way liquorice sticks are eaten; the same use is recorded in Spain (Tardío et al. 2006). Other results have been recorded in Spain regarding the fresh use of the fruit (Aceituno Mata 2010; Morales et al. 2011). The use of this species as a snack is however confirmed for the entire Mediterranean area (Luczaj et al. 2012).

Salads

The subcategories of 'salads' include all plants eaten raw, seasoned with oil, salt or vinegar. They can be eaten alone or mixed to make them taste bitter, sweet, or whatever else you like.

The species frequently used for this purpose are grouped in Fig. 8.

The most commonly used species in the 'salads' category is Portulaca oleracea, which has been mentioned 20 times (Fig. 8). This species is widely used for this purpose both in Italy and abroad. Numerous works have been made across different regions of Italy—Calabria (Nebel et al. 2006; Passalacqua et al. 2006; Lupia and Lupia 2013; Siviglia 2011; Bellusci 2017; Musarella et al. 2019; Mattalia et al. 2020b), Sicilia (Licata et al. 2016; Tavilla et al. 2022), Basilicata (Sansanelli et al. 2017), Puglia (Pieroni and Cattero 2019), Umbria (Ranfa and Bodesmo 2017), and Toscana (Uncini Manganelli et al. 2002; Signorini et al. 2008).

In other parts of Europe, P. oleracea has been used in the same way: in Spain, its taste is highly appreciated (Tardío et al. 2006; Aceituno Mata 2010; Rigat et al. 2016).

Clematis vitalba was mentioned six times for its use in salads. The plant's shoots are consumed in salads but must first be boiled due to their toxicity when eaten raw. This toxicity is common among all plants in the Ranunculaceae family. Boiling the shoots reduces or eliminates the presence of protoanemonin, a compound that can cause skin and gastrointestinal irritation, as well as reducing the bitter taste of young shoots (Corsi and Pagni 1978; Corsi et al. 1981; Bellomaria 1982; Pieroni 1999; Guarrera et al. 2006; Lentini and Venza 2007; Guarrera and Savo 2016). The same use was recorded in Calabria (Mattalia et al. 2020a, b), Campania (Guarino et al. 2008; Savo 2009; Savo et al. 2019), Sicilia (Arcidiacono et al. 2007; Licata et al. 2016), Toscana (Uncini Manganelli et al. 2002), Marche (Lucchetti et al. 2019), Molise (di Tizio et al. 2012) and Sicilia (Biscotti et al. 2018) regions, and the state of Spain (Tardío et al. 2006). In other ethnobotanical research, however, the species is used for other food uses, such as the preparation of omelettes (Corsi et al. 1981; Pieroni 1999; Cornara et al. 2009; Signorini et al. 2008; Ranfa & Bodesmo 2017; Sansanelli et al. 2017), soups (Passalacqua et al. 2006) or as snacks (Scherrer et al. 2005).

Another popular taxon used widely in the food category is Borago officinalis. During this research, it emerged that it is widely used for the preparation of salads (5 citations). Typically, the entire aerial part of the plant is used, but both the leaves and the flowers are also used for decoration. When the leaves are eaten raw, it is advisable to add lemon juice, which softens the stiff, prickly bristles that make the plant shaggy. The plant is often used to alleviate gastrointestinal distress, with edible use associated with therapeutic effects on the digestive system (Arcidiacono et al. 2007). The same use has been found in Calabria (Passalacqua et al. 2006; Bellusci 2017; Mattalia et al. 2020a, b), Campania (Guarino et al. 2008; Savo et al. 2019), Puglia (Leporatti and Guarrera 2007), Sardegna (Lancioni et al. 2007), Toscana (Corsi et al. 1981; Uncini Manganelli et al. 2002), Lombardia (Peroni 2010), Marche (Lucchetti et al. 2019), Liguria (Maccioni et al. 2004), Abruzzo (Tammaro 1984; Manzi 1999) and, in general, throughout the Mediterranean basin (Hadjichambis et al. 2008; Motti et al. 2022). Borago officinalis is, in fact, one of the most widely used species in both northern and southern Italy (Ghirardini et al. 2007).

Omelettes

The use of plants in omelette preparation is widespread in Calabria, with 209 citations and 104 taxa reported in this survey (Fig. 5). The shoots of Asparagus acutifolius make this species the most significant used for this purpose (23 citations) (Fig. 9).

In a study carried out in Spain, shoots of wild A. acutifolius was found to have a more palatable taste than the cultivated Asparagus officinalis L. (Aceituno-Mata 2010).

The use of A. acutifolius turions to prepare omelettes has been found in several Italian regions (Basilicata—Pieroni et al. 2005, Sansanelli et al. 2017, Guarrera et al. 2006; Calabria—Nebel et al. 2006, Musarella et al. 2019; Campania—Savo 2009, Scherrer et al. 2005, Salerno and Guarrera 2008, Savo et al. 2019; Liguria—Cornara et al. 2009; Marche—Taffetani 2005, Lucchetti et al. 2019; Molise—di Tizio et al. 2012; Puglia—Pieroni and Cattero 2019, Biscotti et al. 2018; Sardegna—Lancioni et al. 2007, Signorini et al. 2009; Sicilia—Lentini 2000, Napoli and Giglio 2002, Arcidiacono et al. 2007, 2010, Lentini and Venza 2007, Licata et al. 2016; Toscana—Corsi et al. 1981, Pieroni 1999, Uncini Manganelli et al. 2002, Signorini et al. 2008; Umbria—Ranfa and Bodesmo 2017) but also in Spain (Tardío et al. 2006; Aceituno Mata 2010; Rigat et al. 2016) and the Mediterranean basin (Hadjichambis et al. 2008; Idolo et al. 2010).

Ruscus aculeatus L. is a commonly cited taxon in the preparation of 'omelettes', with 14 references (Fig. 9). Its shoots are utilized similarly to wild asparagus; additionally, researchers have reported that the shoots of R. aculeatus are more bitter and preferred compared to those of A. acutifolius (Arcidiacono et al. 2007).

The use of this taxon has been documented in various regions in southern Italy (Basilicata—Pieroni et al. 2005, Sansanelli et al. 2017; Calabria—Musarella et al. 2019, Mattalia et al. 2020a, b; Campania—Scherrer et al. 2005, Guarino et al. 2008, Savo et al. 2019; Molise—di Tizio et al. 2012; Puglia—Biscotti et al. 2018; Sicilia—Arcidiacono et al. 2007, Lentini and Venza 2007, Licata et al. 2016), slightly less in central and northern Italy (Lombardia—Peroni 2010; Marche—Guarrera 1990, Lucchetti et al. 2019; Toscana—Uncini Manganelli et al. 2002, Signorini et al. 2008; Umbria—Ranfa & Bodesmo 2017). The same traditional use of this plant has been found in Spain (Tardío et al. 2006).

Sambucus nigra L., commonly called elderberry, is a plant utilized for various ethnobotanical purposes: it is considered a medicinal plant for its healing, expectorant and antispasmodic properties (Camangi et al. 2003; Guarrera et al. 2005; Cornara et al. 2014).

The plant is also known in Calabria for the aromatic use of its flowers: these are added to a flatbread to flavour it, called 'pitta china' in Calabrian dialect (Mattalia et al. 2020b; Gentile et al. 2022). This species is globally utilized, and specifically, for this purpose, the use of inflorescences of S. nigra has been recorded in Italy (Italy, in general—Idolo et al. 2010; Basilicata—Sansanelli et al. 2017; Calabria—Passalacqua et al. 2006, Bellusci et al. 2017, Musarella et al 2019, Mattalia et al. 2020a; Campania - Scherrer et al. 2005, Savo 2009, Savo et al. 2019, Motti et al. 2020; Marche—Lucchetti et al. 2019; Liguria—Cornara et al. 2009, 2014; Lombardia—Peroni 2010, Vitalini et al. 2015; Piemonte—Mattalia et al. 2013, Bellia et al. 2015; Sardegna—Lancioni et al. 2007; Toscana—Pieroni 1999, Uncini Manganelli et al. 2002) and internationally (Alarcon et al. 2015; Rigat et al. 2016; Motti et al. 2022).

Conclusions

The results highlight the importance that plants have played and currently play in the ethnobotanical field in Calabria, which, although it is now a globalised territory, still maintains and preserves ancient food traditions. This study is an important contribution to the ethnobotanical knowledge of many plant species: it reports numerous food uses of native and allochthonous plants. Some species native to the study area may be allochthonous in other countries. These data can therefore be a valuable indication of their possible food use, which is currently neglected or underestimated.

Based on the results of this survey, many species could benefit from re-evaluation and further investigation from a phytochemical point of view. In fact, among the information collected, there are numerous confirmations of the presence of nutraceutical compounds in plants used as food, as confirmed by various phytochemical studies. For this reason, studies of this type are becoming increasingly desirable on a global scale to discover the nutraceutical potential of many other plants that have so far only been used as food.

Even in present times, the utilization of wild and cultivated plants remains prevalent among the populations living in Calabria. This practice was observed across groups with different historical origins such as Arbëreshë, Occitans, Graecanic, and the autochthonous Calabrians. The multifaceted Calabrian people demonstrate to have a large and diversified knowledge about the use of plants for food purposes. While some species appear to be favoured over others, this preference likely arises from their greater prevalence and wider distribution not only within Calabria but also throughout Italy and the broader Mediterranean region.

Among the various strategies that could serve to revalue and enhance ethnobotanical information is the domestication of wild species that are still widely used. This idea can facilitate the possibility of making the use of these plants more accessible and, above all, through the study of specific cultivation protocols, make these plants more resistant to climate change and all anthropic and other threats. Additionally, these species could be considered for commercialization, thereby expanding the range of options available to local consumers. Such an approach holds the promise of fostering a more localized and equitable economy, while concurrently mitigating production costs in agriculture. Plants that are discovered as food can be used by local farms and agrotourism establishments to promote the domestication of the species or to create new dishes that would have typical local characteristics. This strategy would have the added advantage of reducing water consumption, positively impacting the reduction of CO2 emissions. By leveraging the innate attributes of these species, which are already well-adapted to the local climate, this initiative can maximize their potential. Despite the evident effects of climate change, this agricultural model based on ethnobotany studies could be adapted to other regions worldwide with positive outcomes on a planetary scale, according to the urgent directive of “thinking globally, acting locally”.

Unfortunately, this work is not enough to fill the gap in knowledge regarding the food use of plants in the Calabria region, however, new studies are already being conducted to implement this knowledge.

Data availability

All the data are available in the Supplementary files.

References

Aceituno Mata L (2010) Estudio etnobotánico y agroecológico de la Sierra Norte de Madrid.

Alarcόn R, Pardo-de-Santayana M, Priestley C, Morales R, Heinrich M (2015) Medicinal and local food plants in the south of Alava (Basque Country, Spain). J Ethnopharmacol 176:207–224

Arcidiacono S, Napoli M, Oddo G, Pavone P (2007) Piante selvatiche d’uso popolare nei territori di Alcara Li Fusi e Militello Rosmarino (Messina, NE Sicilia). Quad Bot Amb Appl 18:103–144

Arcidiacono S, Costa R, Marletta G, Pavone P, Napoli M (2010) Usi popolari delle piante selvatiche nel territorio di Villarosa (EN–Sicilia Centrale). Quad Bot Amb Appl 1:95–118

Ardenghi NMG, Ballerini C, Bodino S, Cauzzi P, Guzzon F (2017) “Lándar”, “Lándra”, “Barlánd” (Bunias erucago L.): a Neglected crop from the Po Plain (Northern Italy). Econ Bot 71:288–295

Barbaro G, Bombino G, Foti G, Barillà GC, Puntorieri P, Mancuso P (2022) Possible increases in floodable areas due to climate change: the case study of Calabria (Italy). Water 14(14):2240

Bartolucci F, Peruzzi L, Galasso G, Alessandrini A, Ardenghi NMG, Bacchetta G, Conti F (2024) A second update to the checklist of the vascular flora native to Italy. Plant Biosyst 158(2):219–296. https://doi.org/10.1080/11263504.2024.2320126

Baydoun SA, Kanj D, Raafat K, Aboul Ela M, Chalak L, Arnold-Apostolides N (2017) Ethnobotanical and economic importance of wild plant species of Jabal Moussa Bioreserve. Lebanon J Ecosyst Ecography 7(3):1–10

Baydoun S, Hani N, Nasser H, Ulian T, Arnold-Apostolides N (2023) Wild leafy vegetables: A potential source for a traditional Mediterranean food from Lebanon. Front Sustain Food Syst 6:991979

Bellia G, Pieroni A (2015) Isolated, but transnational: the glocal nature of Waldensian ethnobotany, Western Alps, NW Italy. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 11:1–20

Bellomaria B (1982) Le piante di uso popolare nel territorio di Camerino (Marche). Archivio Botanico e Biogeografico Italiano 58(3/4):1–27

Bellusci F (2017) Le piante officinali del Parco Nazionale del Pollino. Università di Pisa, Tesi di laurea

Bernardo L (2000) Fiori e piante del Parco del Pollino, 2nd edn. Prometeo, Castrovillari (Cosenza)

Biscotti N, Del Viscio G, Bonsanto D (2018) Indagine etnobotanica sull’uso alimentare tradizionale di piante selvatiche in un comprensorio montano della regione Puglia (Subappennino Dauno, Provincia di Foggia). Atti Soc. Tosc Sci Nat Mem Ser B 125:17–29

Camangi F, Stefani A, Tomei PE (2003) Il Casentino: tradizioni etnofarmacobotaniche nei comuni di Poppi e Bibbiena (Arezzo-Toscana). Atti Soc Tosc Sci Nat Mem Ser B 110:55–69

Camarda I, Carta L, Vacca G, Brunu A (2017) Les plantes alimentaires de la Sardaigne: Un patrimoine ethnobotanique et culturel d’ancienne origine. Flora Mediterr 27:77–90

Cano E, Cano-Ortiz A, Musarella CM, Piñar Fuentes JC, Quinto-Canas R, Spampinato G, Pinto Gomes CJ (2019) Endemic and Rare Species of Asteraceae from the Southern Iberian Peninsula: Ecology, Distribution and Syntaxonomy. In AA.VV. Asteraceae: Characteristics, Distribution and Ecology; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA; pp. 147–175. ISBN 9781536166323.

Cantasano N, Caloiero T, Pellicone G, Aristodemo F, De Marco A, Tagarelli G (2021) Can ICZM contribute to the mitigation of erosion and of human activities threatening the natural and cultural heritage of the coastal landscape of Calabria? Sustainability 13(3):1122

Caruso G (2022) Anthyllis hermanniae L. subsp. brutia Brullo & Giusso (Fabaceae) population survey and conservation tasks. Res J Ecol Environ Sci. 2(4):92–102. https://doi.org/10.31586/rjees.2022.339

Comes HP (2004) The Mediterranean region: a hotspot for plant biogeographic research. New Phytol 164:11–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01194.x

Cornara L, La Rocca A, Marsili S, Mariotti MG (2009) Traditional uses of plants in the Eastern Riviera (Liguria, Italy). J Ethnopharmacol 125(1):16–30

Cornara L, La Rocca A, Terrizzano L, Dente F, Mariotti MG (2014) Ethnobotanical and phytomedical knowledge in the North-Western Ligurian Alps. J Ethnopharmacol 155(1):463–484

Corsi G, Pagni AM (1978) Studi sulla flora e vegetazione del Monte Pisano (Toscana nord-occidentale). 1. Le piante della medicina popolare nel versante pisano. Webbia 33(1):159–204

Corsi G, Gaspari G, Pagni AM (1981) L’uso delle piante nell’economia domestica della Versilia collinare e montana. Atti Soc Tosc Sci Nat Mem Ser B 87:309–386

di Tizio A, Łuczaj ŁJ, Quave CL, Redžić S, Pieroni A (2012) Traditional food and herbal uses of wild plants in the ancient South-Slavic diaspora of Mundimitar/Montemitro (Southern Italy). J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 8(1):1–10

Estrada-Castillón E, Villarreal-Quintanilla JÁ, Cuéllar-Rodríguez LG, March-Salas M, Encina-Domínguez JA, Himmeslbach W, Salinas-Rodríguez MM, Guerra J, Cotera-Correa M, Scott-Morales LM et al (2022) Ethnobotany in Iturbide, Nuevo León: the traditional knowledge on plants used in the semiarid mountains of Northeastern Mexico. Sustainability 14(19):12751

Galasso G, Conti F, Peruzzi L, Alessandrini A, Ardenghi NMG, Bacchetta G, Bartolucci F (2024) A second update to the checklist of the vascular flora alien to Italy. Plant Biosyst. 158(2):297–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/11263504.2024.2320129

Gentile C, Spampinato G, Patti M, Laface VLA, Musarella CM (2022) Contribution to the ethnobotanical knowledge of Serre Calabre (Southern Italy). Res J Ecol Environ Sci 2(3):35–55. https://doi.org/10.31586/rjees.2022.389

Ghirardini MP, Carli M, Del Vecchio N, Rovati A, Cova O, Valigi F, Pieroni A (2007) The importance of a taste. A comparative study on wild food plant consumption in twenty-one local communities in Italy. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 3(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-3-22

Guarino C, De Simone L, Santoro S (2008) Ethnobotanical study of the Sannio area, Campania, S Italy

Guarrera PM (1990) Usi tradizionali delle piante in alcune aree marchigiane. Inf Bot Ital 22(3):155–167

Guarrera PM, Savo V (2016) Wild food plants used in traditional vegetable mixtures in Italy. J Ethnopharmacol 185:202–234

Guarrera PM, Forti G, Marignoli S (2005) Ethnobotanical and ethnomedicinal uses of plants in the district of Acquapendente (Latium, Central Italy). J Ethnopharmacol 96(3):429–444

Guarrera PM, Salerno G, Caneva G (2006) Food, flavouring and feed plant traditions in the Tyrrhenian sector of Basilicata, Italy. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 2:1–6

Hadjichambis AC, Paraskeva-Hadjichambi D, Della A, Pieroni A (2008) Wild and semi-domesticated food plant consumption in seven circum-Mediterranean areas. Int J Food Sci Nutr 59(5):383–414

Hadush M, Holden ST, Tilahun M (2019) Does population pressure induce farm intensification? Empirical evidence from Tigrai Region. Ethiopia Agric Econ 50:259–277

Helstosky C (2009) Food culture in the Mediterranean. Bloomsbury Publishing, USA

Idolo M, Motti R, Mazzoleni S (2010) Ethnobotanical and phytomedicinal knowledge in a long-history protected area, the Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park (Italian Apennines). J Ethnopharmacol 127(2):379–395

Jensen M, Pliscoff P (2023) Endemic crop wild relatives in Chile towards the end of the 21st century: protected areas and agricultural expansion. Crop Sci 63:2241–2254

Khan N, Badshah L, Shah SM, Khan S, Shah AA, Muhammad M, Ali K (2021) Ecological, ethnobotanical and phytochemical evaluation of plant resources of Takht Bhai, district Mardan, KPK Pakistan. Turk J Physiother Rehabil. 32(3):15970–15985

Kremezi A (2000) The Foods of the Greek Islands: Cooking and culture at the crossroads of the Mediterranean. HMH

Laface VLA, Musarella CM, Tavilla G, Cambria S, Maruca G, Giusso del Galdo G, Spampinato G (2023) Carpological analysis of two endemic Italian species: Pimpinella anisoides and Pimpinella gussonei (Apiaceae). Plants 12(5):1083. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12051083

Lancioni MC, Ballero M, Mura L, Maxia A (2007) Usi alimentari e terapeutici nella tradizione popolare del Goceano (Sardegna Centrale). Atti Soc Tosc Sci Nat Mem Ser B 114:45–56

Lentini F (2000) The role of ethnobotanics in scientific research. State of ethnobotanical knowledge in Sicily. Fitoterapia 71:S83–S88

Lentini F, Venza F (2007) Wild food plants of popular use in Sicily. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 3:1–12

Leporatti ML, Guarrera PM (2007) Ethnobotanical remarks in Capitanata and Salento areas (Puglia, southern Italy). Etnobiología 5(1):51–64

Licata M, Tuttolomondo T, Leto C, Virga G, Bonsangue G, Cammalleri I, La Bella S (2016) A survey of wild plant species for food use in Sicily (Italy)–results of a 3-year study in four regional parks. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 12:1–24

Lombardi T, Ventura I, Bertacchi A (2023) Floristic inventory of ethnobotanically important halophytes of North-Western Mediterranean coastal Brackish Areas, Tuscany. Italy Agronomy 13(3):615

Lovrić N, Fraccaroli C, Bozzano M (2023) A future EU overall strategy for agriculture and forest genetic resources management: finding consensus through policymakers’ participation. Futures 151:103179

Lucchetti L, Zitti S, Taffetani F (2019) Ethnobotanical uses in the Ancona district (Marche region, Central Italy). J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 15(1):1–33

Luczaj L, Pieroni A, Tardío J, Pardo-de-Santayana M, Sõukand R, Svanberg I, Kalle R (2012) Wild food plant use in 21st century Europe, the disappearance of old traditions and the search for new ciusines involving wild edibles. Acta Soc Bot Pol Pol 81(4):359–370. https://doi.org/10.5586/asbp.2012.031

Lupia C, Lupia R (2013) Etnobotanica: piante e tradizioni popolari di Calabria. Viaggio alla scoperta di antichi saperi intorno al mondo delle piante. Crotone: Grafi.Co.

Maccioni S, Monti G, Flamini G, Cioni PL, Morelli I, Guazzi E (2004) Ricerche etnobotaniche in Liguria. La val Lerrone e la bassa valle Arroscia. Atti Soc Toscana Sci Nat Mem Ser B 111:129–134

Manzi A (1999) Le piante alimentari in Abruzzo. Chieti: Casa Editrice Tinari.

Marziliano P, Lombardi F, Menguzzato G, Scuderi A, Altieri V, Coletta V, Marcianò C (2016) Biodiversity Conservation in Calabria Region (Southern Italy): Perspectives of Management in the Sites of the ‘Natura 2000’Network. In: Proceedings of the international conference on research for sustainable development in mountain regions; Instituto Politécnico: Bragança, Portugal

Mattalia G, Quave CL, Pieroni A (2013) Traditional uses of wild food and medicinal plants among Brigasc, Kyé and Provençal communities on the West Italian Alps. Genet Resour Crop Evol 60:587–603

Mattalia G, Sõukand R, Corvo P, Pieroni A (2020a) Blended divergences: Local food and medicinal plant uses among Arbëreshë, Occitans, and autochthonous Calabrians living in Calabria, Southern Italy. Plant Biosyst 154(5):615–626

Mattalia G, Paolo C, Pieroni A (2020b) The virtues of being peripheral, recreational, and transnational: local wild food and medicinal plant knowledge in selected remote municipalities of Calabria, Southern Italy. Ethnobot Res Appl 19:1–9. https://doi.org/10.32859/era.19.38.1-20

Menale B, Amato G, Di Prisco C, Muoio R (2006) Traditional uses of plants in north-western Molise (Central Italy). Delpinoa 48:29–36

Monari S, Ferri M, Salinitro M, Tassoni A (2022) Ethnobotanical review and dataset compiling on wild and cultivated plants traditionally used as medicinal remedies in Italy. Plants 11(15):2041

Mongalo NI, Raletsena MV (2023) Fabaceae: South African medicinal plant species used in the treatment and management of sexually transmitted and related opportunistic infections associated with HIV-AIDS. Data 8(11):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/data8110160

Morales Valverde R, Tardío J, Pardo de Santayana M, Molina M, Aceituno-Mata L (2011). Biodiversidad y Etnobotánica en España

Motti R, Bonanomi G, Lanzotti V, Sacchi R (2020) The contribution of wild edible plants to the Mediterranean diet: an ethnobotanical case study along the coast of Campania (Southern Italy). Econ Bot 74:249–272

Motti R, Bonanomi G, de Falco B (2022) Wild and cultivated plants used in traditional alcoholic beverages in Italy: an ethnobotanical review. Eur Food Res Technol 248(4):1089–1106

Musarella CM, Paglianiti I, Cano-Ortiz A, Spampinato G (2019) Indagine etnobotanica nel territorio del Poro e delle Preserre calabresi (Vibo Valentia, S-Italia). Atti Soc. Tosc Sci Nat Mem Ser B 126:13–28. https://doi.org/10.2424/ASTSN.M.2018.17

Musarella CM, Brullo S, del Galdo GG (2020) Contribution to the orophilous cushion-like Vegetation of Central-Southern and insular Greece. Plants 9(12):1678. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9121678

Napoli M, Giglio T (2002) Usi popolari di piante spontanee nel territorio di Monterosso Almo (Ragusa). Boll Accad Gioenia Sci Nat 35(361):361–401

Nebel S, Pieroni A, Heinrich M (2006) Ta chòrta: wild edible greens used in the Graecanic area in Calabria, Southern Italy. Appetite 47(3):333–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2006.05.010

Passalacqua NG, De Fine G, Guarrera PM (2006) Contribution to the knowledge of the veterinary science and of the ethnobotany in Calabria region (Southern Italy). J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 2:1–14

Pasta S, La Rosa A, Garfì G, Marcenò C, Silvestre Gristina A, Carimi F, Guarino R (2020) An updated checklist of the Sicilian native edible plants: preserving the traditional ecological knowledge of century-old agro-pastoral landscapes. Front Plant Sci 11:388

Patti M, Musarella CM, Postiglione SM, Falcone MC, Mammone G, Papalia F, Zappalà MA, Laface VLA, Spampinato G (2024) Ethnobotanical studies on the Tyrrhenian side of Aspromonte Massif (Southern Italy). Plant Biosyst 158(3):545–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/11263504.2024.2336601

Peroni G (2010) Usi alimentari delle piante selvatiche (regione Insubrica: Lombardia nord-occidentale e Canton Ticino): profilo storico e situazione attuale con note di etnofarmacologia ed etnobotanica. Università Politecnica delle Marche

Perrino EV, Perrino P (2020) Crop wild relatives: know how past and present to improve future research, conservation and utilization strategies, especially in Italy: a review. Genet Resour Crop Evol 67:1067–1105

Pieroni A (1999) Gathered wild food plants in the upper valley of the Serchio river (Garfagnana), central Italy. Econom Bot 53:327–341

Pieroni A, Cattero V (2019) Wild vegetables do not lie: Comparative gastronomic ethnobotany and ethnolinguistics on the Greek traces of the Mediterranean diet of southeastern Italy. Acta Bot Brasilica 33:198–211

Pieroni A, Quave CL (2005) Traditional pharmacopoeias and medicines among Albanians and Italians in southern Italy: a comparison. J Ethnopharmacol 101(1–3):258–270

Pieroni A, Nebel S, Santoro RF, Heinrich M (2005) Food for two seasons: culinary uses of non-cultivated local vegetables and mushrooms in a south Italian village. Int J Food Sci Nutr 56(4):245–272

Pignatti S (1982) Flora d’Italia (Ed. Agricole, Bologna, Italy), 1 vol

Pignatti S, Guarino R, La Rosa M, editors (2017a) Flora d’Italia. Ed.2. Vol. 1. Edagricole. Bologna, Italy

Pignatti S, Guarino R, La Rosa M, editors (2017b) Flora d’Italia. Ed.2. Vol. 2. Edagricole. Bologna, Italy

Pignatti S, Guarino R, La Rosa M, editors (2018) Flora d’Italia. Ed.2. Vol. 3. Edagricole. Bologna, Italy

Pignatti S, Guarino R, La Rosa M, editors (2019) Flora d’Italia. Ed.2. Vol. 4. Edagricole. Bologna, Italy

Ranfa A, Bodesmo M (2017) An ethnobotanical investigation of traditional knowledge and uses of edible wild plants in the Umbria Region, Central Italy. J Appl Bot Food Qual 90:246–258

Raunkiaer C (1934) The life forms of plants and statistical plant geography; being the collected papers of C. Raunkiær. The life forms of plants and statistical plant geography.

Renna M, Rinaldi VA, Gonnella M (2015) The Mediterranean diet between traditional foods and human health: the culinary example of Puglia (Southern Italy). Int J Gastron Food Sci 2(2):63–71

Rigat M, Gras A, D’Ambrosio U, Garnatje T, Parada M, Vallès J (2016) Wild food plants and minor crops in the Ripollès district (Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula): potentialities for developing a local production, consumption and exchange program. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 12(1):1–16

Rivas-Martínez S, Rivas-Saenz S, Penas A (2002) Worldwide bioclimatic classification system. Kerkwerve, The Netherlands: Backhuys Pub

Salerno G, Guarrera PM (2008) Ricerche etnobotaniche nel Parco Nazionale del Cilento e Vallo di Diano: il territorio di Castel San Lorenzo (Campania, Salerno). Inf Bot It 40(2):165–181

Sansanelli S, Ferri M, Salinitro M, Tassoni A (2017) Ethnobotanical survey of wild food plants traditionally collected and consumed in the Middle Agri Valley (Basilicata region, southern Italy). J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 13(1):1–11

Savo V (2009) Ethnobotanical analysis in the Amalfi Coast and evaluation of results on a scientific and economic point of view (Doctoral dissertation, University of Roma Tre)

Savo V, Salomone F, Mattoni E, Tofani D, Caneva G (2019) Traditional salads and soups with wild plants as a source of antioxidants: a comparative chemical analysis of five species growing in central Italy. Evid Based Complement Altern Med 2019:6782472. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/6782472

Scherrer AM, Motti R, Weckerle CS (2005) Traditional plant use in the areas of Monte Vesole and Ascea, Cilento national park (Campania, Southern Italy). J Ethnopharmacol 97(1):129–143

Semeraro T, Scarano A, Leggieri A, Calisi A, De Caroli M (2023) Impact of Climate change on agroecosystems and potential adaptation strategies. Land 12(6):1117

Signorini MA, Lombardini C, Bruschi P, Vivona L (2008) Conoscenze etnobotaniche e saperi tradizionali nel territorio di San Miniato (Pisa). Atti Soc Tosc Sci Nat Mem Ser B 114:65–83

Signorini MA, Piredda M, Bruschi P (2009) Plants and traditional knowledge: an ethnobotanical investigation on Monte Ortobene (Nuoro, Sardinia). J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 5(1):1–14

Siviglia M (2011) Piante selvatiche di interesse alimentare nelle Serre Calabre – Riconoscerle e raccoglierle, New Bit Print, Serra San Bruno (VV), 140 pp

Spampinato G (2014) Guida alla flora dell'Aspromonte. Reggio Calabria: Italy. Laruffa Editore.

Spampinato G, Crisarà R, Cannavò S, Musarella CM (2017) Phytotoponims of southern Calabria: a tool for the analysis of the landscape and its transformations. Atti Soc Tosc Sc Nat Mem Ser B 124:61–72. https://doi.org/10.2424/ASTSN.M.2017.06

Spampinato G, Crisarà R, Cameriere P, Cano-Ortiz A, Musarella CM (2022) Analysis of the forest landscape and its transformations through phytotoponyms: a case study in Calabria (S-Italy). Land 11(4):518. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11040518

Taffetani F (2005) Rugni, speragne crispigne. Piante spontanee negli usi e nelle tradizioni del territorio maceratese

Tammaro, F (1984). Flora officinale d'Abruzzo. A cura del Centro servizi culturali

Tardío J, Pardo-de-Santayana M (2008) Cultural importance indices: a comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of Southern Cantabria (Northern Spain). Econom Bot 62:24–39

Tardío J, Pardo-de-Santayana M, Morales R (2006) Ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants in Spain. Bot J Linn 152(1):27–71

Tavilla G, Crisafulli A, Ranno V, Picone RM, Redouan FZ, Giusso del Galdo G (2022) First contribution to the ethnobotanical knowledge in the Peloritani Mounts (NE Sicily). Res J Ecol Environ Sci 2(3):1–34. https://doi.org/10.31586/rjees.2022.201

Uncini Manganelli RE, Camangi F, Tomei PE, Oggiano N (2002) L’uso delle erbe nella tradizione rurale della Toscana. ARSIA, Firenze

Vitalini S, Puricelli C, Mikerezi I, Iriti M (2015) Plants, people and traditions: Ethnobotanical survey in the Lombard Stelvio National Park and neighbouring areas (Central Alps, Italy). J Ethnopharmacol 173:435–458

Zocchi DM, Bondioli C, Hamzeh Hosseini S, Miara MD, Musarella CM et al (2022) Food security beyond cereals: a cross-geographical comparative study on acorn bread heritage in the Mediterranean and the Middle East. Foods 11(23):3898. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11233898

Funding

This work was carried out with the support of the National Operational Program (PON) "Research and Innovation" 2014–2020 n. CCI2014IT16M2OP005, Thematic Area Action IV.5 "Additional PhD scholarships on green topics".

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CMM: had the idea for the article, performed the literature search, drafted the original manuscript, provided resources and supervised the project; MP: performed the literature search and data analysis, wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript; VLAL: provided resources and drafted the original manuscript; GS: supervised, provided resources and performed formal analysis. All authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not applicable in this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Musarella, C.M., Patti, M., Laface, V.L.A. et al. An overview of ethnobotanical knowledge for the enhancement of typical plant food and the development of a local economy: the case of Calabria region (Southern Italy). Vegetos (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42535-024-00975-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42535-024-00975-4