Abstract

The emergence of linked socio-ecological systems as an organizing concept over the last two decades casts the legacy of Aldo Leopold in a new light, allowing us to view him as a key forerunner in this interdisciplinary field. Leopold regarded “land” as the nexus of human and natural systems and framed his “land ethic” as a guide to appropriate human thought and action within them. Our understanding of Leopold’s legacy, and of the land ethic itself, continues to evolve in response to rapidly changing social and ecological conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 A forerunner in defining socio-ecological systems

Seventy years after the posthumous publication of his classic work A Sand County Almanac (Leopold 1949), Aldo Leopold remains a key figure in the evolution of environmental thought and practice. Although Leopold was grounded professionally in older approaches of utilitarian conservation and nature protection, he strove across his lifetime to reconcile these contrasting approaches, based on his awareness of complex social, economic, and ecological change. Leopold was born in 1887 in the Midwestern USA, in an emerging economic landscape dominated by railroads, river transport, horsepower, and the telegraph. He died in 1948, living just long enough to see the post-World War II world being rapidly transformed by automobiles, air travel, fossil fuels, nuclear power, and instantaneous communications. He matured in his thinking as the science of ecology matured and as environmental pressures mounted (Flader 1994; Warren 2016). He asked himself, with as much resolve as anyone of his generation, what this new science of relationship and connectivity meant for the never-ending human search for “a durable scale of values” in a time of rapid change (Leopold 1949, p. 200).

He asked, moreover, what these ethical insights and ecological knowledge meant for the land—his preferred term for the community of life that embraced “soil, water, plants, animals, and people” (Leopold 1942, p. 265). Arthur Tansley had coined the term ecosystem in 1935. Leopold apparently never used the neologism. In the Almanac and his other writings, he deployed his own suite of metaphors for ecosystems (some negative and some positive): community, mechanism, organism, symphony, clock, fountain, factory, etc. One reason Leopold still seems so strikingly current to us is that he acknowledged the deeply intertwined reality of social and ecological systems:

There are two things that interest me: the relation of people to each other, and the relation of people to land (Meine 2010, p. 51).

Conservation, viewed in its entirety, is the slow and laborious unfolding of a new relationship between people and land (Leopold 1940, p. 2).

Land ecology is putting the sciences and arts together for the purposes of understanding our environment. …Land ecology discards at the outset the fallacious notion that the wild community is one thing, the human community another. What are the sciences? Only categories for thinking. Sciences can be taught separately, but they can’t be used separately, either for seeing land or for doing anything with it (Leopold [1942] 1991), pp. 302–303).

At a time when he and his contemporaries were still laboring to unify plant and animal ecology, Leopold was also endeavoring to conjoin the social and natural sciences, as well as history, philosophy, literature, and the arts. Since the advent of the industrial age (if not the agricultural revolution), humanity’s alienation from nature had advanced to the point where it threatened society’s “own future continuity” (Leopold [1935] 1991, p. 220). By the mid-twentieth century, modernity had defined itself in terms of humanity’s physical, psychological, and spiritual distance from the more-than-human world. Centuries of colonization, commodification, and exploitation of land and people had brought the world to a dangerous brink. As one well familiar with rimrock and cliff edges, Leopold saw that progress consisted not in moving blindly ahead in the same direction, but in questioning the standard notion of progress itself. This required, in turn, a more comprehensive concept of community.

At the Seventh North American Wildlife Conference, held in Toronto, Canada, in April 1942, Leopold delivered a short paper entitled “The Role of Wildlife in a Liberal Education.” His presentation included a figure labeled “Lines of dependency (food chains) in a community.” [See Figure 1 in Van Auken (2020).] Three-quarters of a century later, that figure remains transformative, even revolutionary. It depicts a typical (if simplified) set of ecological relationships in the agricultural landscape of Wisconsin, USA, where Leopold spent the latter half of his career and taught at the University of Wisconsin. The figure shows links connecting rock—soil—ragweed—quail—horned owl, and rock—soil—alfalfa—rabbit—red-tailed hawk. The study of such “lines of dependency” had become increasingly important in Leopold’s work, especially after British ecologist Charles Elton, Leopold’s friend and colleague, published his landmark book Animal Ecology (1927). Elton’s volume defined such basic ecological concepts as the niche, food webs, and the pyramid of numbers.

In his writing, teaching, and research, Leopold often depicted such ecological relationships. On this occasion, however, he pushed into conceptual territory where few other ecologists ventured. The ecological chain that led from rock to soil to alfalfa to cow Leopold extended to connect cow to farmer to grocer to lawyer to student. Another line linked farmer to implement maker to mechanic to union secretary. In his diagram, Leopold also highlighted the various academic fields required to understand the workings of the entire land community. He included, as would be expected, geology, soils, botany, mammalogy, and ornithology. But Leopold also included animal husbandry, sociology, and economics. For Leopold, human and natural communities were intimately intermingled. Our social, economic, and political realities did not, and could not, exist in an ecological vacuum. Our conservation challenges, it followed, could not be addressed apart from the social sphere.

Over the last two decades, in the effort to comprehend the full complexity and dynamism of interconnected human–nature relationships, researchers in the social and natural sciences have come to define and study linked (or coupled) socio-ecological systems. Socio-Ecological Practice Research (SEPR) itself is a product of the expansion of this perspective and approach (Xiang 2019). Over the decades, readers and critics have defined many different “Leopolds”: Leopold the wilderness defender and the pioneer in land restoration, Leopold the deep ecologist and the eco-pragmatist, Leopold the agrarian conservative and the progressive reformer (Meine 2004). Now we can highlight another Leopold, one who understood “the land” as a place where human and natural systems interpenetrate, and so helped importantly to forge this interdisciplinary field (Meine 2020).

2 Leopold and systems thinking in a time of rapid change

It is timely that we do so. Recognition of pervasive human environmental impacts obliges us to regard all ecosystems as, in some manner and to some degree, socio-ecological systems (Reyers et al. 2018). Such systems exist at all spatial scales, from the backyard and watershed to the continent and the Earth. Such systems comprise varied subsystems and are nested within yet larger systems. Such systems are constantly changing over all temporal scales, from the momentary to the millennial and beyond (Norton 2015). Such dynamic socio-ecological systems are not deterministic in their rates and types of change, but reflect human agency at work in the systems in which humans are embedded. It was Leopold’s conviction, based on his understanding of changes in the land and in human ethical frameworks, that our agency could be damaging or ameliorative depending on the values we recognize and the choices we make. Hence, his call for a land ethic “as a mode of guidance for meeting ecological situations so new or intricate, or involving such deferred reactions, that the path of social expediency is not discernible to the average individual” (Leopold 1949, p. 203; emphasis by the author).

Leopold composed his essay “The Land Ethic” in July 1947 as he was preparing what would turn out to be the final version of the manuscript of A Sand County Almanac (Meine 1987, p. 174). The date of composition is relevant. On a personal level, Leopold, along with so many of his contemporaries, was trying to make sense of the great disruptions of economic depression, widespread environmental damage, and global conflict that rocked the world in the 1930s and 1940s. More broadly, Leopold was synthesizing his statement of conservation philosophy at the outset of what contemporary observers now look back on as the “Great Acceleration”—the dramatic and synchronous increase in human economic activity and environmental impacts since 1950, involving multiple socioeconomic and ecological trends (Steffen et al. 2015). This concurrence offers us a useful historical benchmark against which to measure not only trends in our socio-ecological systems, but in our ethical response to those trends.

Three generations later, the consequences of the Great Acceleration are well recognized and reiterated with every new summary report and news headline highlighting the climate crisis, biodiversity loss, the state of the oceans, emerging diseases, and other aspects of global change. Three decades of concerted effort to adopt sustainability as a guiding principle have influenced discourse on social, economic, and environmental goals, but have had limited effects on the trends themselves. The result is the precarious moment in human history in which we find ourselves. One way to understand the current state of public life and of the institutions of government is as a response to the unprecedented, rapid, synergistic, and still accelerating forms of change we are experiencing. This premise can be broken down into several propositions:

Our times are marked by a complex interaction of social, economic, technological, demographic, political, and environmental changes.

Attitudes toward these changes do not follow a simple or predictable pattern. In fact, our times are also marked by divergent and conflicting views on the kinds of change that we are experiencing and the kinds of changes we ought to seek.

These diverse views fall along a complex set of cultural fault lines. On the one hand, some forms of socio-ecological change invite resistance, denial, anger, desperation, and fear. Other kinds of change inspire excitement and a desire for positive and progressive change.

Political forces are aligned to both exploit and drive those divergent viewpoints.

There are, no doubt, other features that characterize personal, public, and political responses to the contemporary socio-ecological landscape. All underscore the basic point. We find ourselves anxious and divided amid the intensifying maelstrom of change. Many—professionals and the general public alike—find themselves coping with despair and grief (Robbins and Moore 2013; Cunsolo and Ellis 2018). Political systems and institutions that evolved in more stable times are ill-suited to respond to the magnitude and complexity of changes now at hand. Simon Lewis, Professor of Global Change Science at the University College London, UK, has observed “This century will be marked by rapid social and environmental change; that is certain. What is less clear is if societies can make wise political choices to avoid disaster in the future” (Harrabin 2019).

The need for science to inform “wise political choices” helps to explain the remarkable ascendance of socio-ecological systems as an organizing concept over the last two decades. Schoon and Van der Leeuw (2015, p. 166) show how, in this period, “a growing community of social and natural scientists have united to utilize a social-ecological systems framework to take a more holistic and transdisciplinary approach to science.” Why this emergence, and why now? What accounts for the heightened attention to linked socio-ecological systems?

Perhaps those are simply other ways of asking what value, in general, systems thinking offers. Albert Einstein provided an answer: “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” The journalist H. L. Mencken offered another: “There is always a well-known solution to every human problem—neat, plausible, and wrong.” That both these oft-quoted maxims are, in fact, suspect in their provenance only proves the point: There is a widespread hunger for effective solutions to complex problems. Although we always need more data, we need more than data points. We need to make sense of that data. For “data is not information, information is not knowledge, knowledge is not understanding, understanding is not wisdom.” (Another vaguely sourced aphorism, attributed variously to Einstein, astronomer Clifford Stoll, and genre-bending musician Frank Zappa!)

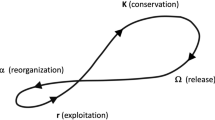

Systems thinking, we might say more prosaically, is necessary to critical thinking. It is necessary to comprehend reality and understand complexity. It is necessary to sustainability at every scale. It is necessary to problem-solving. And it is especially necessary to resolve “wicked” problems (Rittel and Webber 1973). In these times of rapid change, we cannot solve separate problems in isolation; systemic problems require systemic solutions. Solutions to each problem must also contribute to the solution of other, related problems. Solutions must avoid the problems and “pathologies” that reductionism and over-specialization can invite (Holling and Meffe 1996). Ensuring the resilience of our socio-ecological systems may be the ultimate wicked problem—or, as Leopold phrased it, “the oldest task in human history” (Leopold [1938] 1991), p. 254).

Back in that summer of 1947, at the dawn of the Great Acceleration, as systems theory was coalescing, Aldo Leopold was organizing his thoughts on paper. Having worked his way to hard-won wisdom, sometimes through his own mistakes, he communicated these views and needs in his inimitable way. In the foreword to A Sand County Almanac, he wrote: “Our bigger-and-better society is now like a hypochondriac, so obsessed with its own economic health as to have lost the capacity to remain healthy. The whole world is so greedy for more bathtubs that it has lost the stability necessary to build them, or even to turn off the tap” (Leopold 1949, p. ix). At a time wracked by social, economic, and environmental instability, Leopold did not by “stability” imply a desire to return to some static state. Rather, he was concerned with what he called land health: the capacity of the land (or socio-ecological system) for self-regulation and self-renewal (Berkes et al. 2012). Conservation was “our effort to understand and preserve this capacity” (Leopold 1949, p. 221).

Progress in conservation required “a shift of values” that demonstrated an awareness of ecological connections and respect for “fellow-members [of the land community], and also respect for the community as such” (Leopold 1949, pp. ix, 204). Leopold held no illusions about “the magnitude of the task…. It has required nineteen centuries to define decent man-to-man conduct and the process is only half done; it may take as long to evolve a code of decency for man-to-land conduct” (Leopold [1947] 1991, pp. 343, 345–346). Leopold was a realist, his “outlook” reflecting his pragmatism and his grasp of history and the human condition. Such perspective is also instructive for understanding both the development of socio-ecological systems thinking as well as Leopold’s special contributions to it.

3 Socio-ecological systems in historical perspective

In times of unprecedented change, that historical perspective may seem less relevant. The past may seem a wholly inadequate guide in facing rapid change. The historian, of course, argues the opposite: that it is more important than ever to know how and why society has arrived at this point. And the better we know the past, the more effectively we can calibrate the changes we are experiencing and seek common ground for positive progress. Part of that work involves striving for a more informed and inclusive narrative of the concept of socio-ecological systems and related ideas of sustainability and resilience. That history is vital, not simply because it is “nice to know,” but because it shapes fundamentally how we frame our own approaches and applications.

Recent histories of sustainability demonstrate that, however new specific terms and phrases may be, the underlying ideas have a rich lineage (Djalali and Vollaard 2008; Grober 2012; Caradonna 2014). The threads of sustainability thinking have come together from varied geographical and cultural sources. These sources importantly include indigenous and non-Western knowledge systems. It seems no accident that the manifestation of sustainability, resilience, and socio-ecological systems as organizing ideas over the last several decades has coincided with the recognition of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and ecological wisdom in the scientific community (Berkes et al. 2000; Kimmerer 2011; Wang et al. 2016; Wang 2019; Xiang 2014). Behind the convergence of these systems of thought is a shared need to find meaning and coherence amid the myriad data points.

Within the dominant scientific tradition, we find deep roots of socio-ecological systems thinking among early natural scientists with an appreciation of human cultural contexts and implications, and among early social scientists with an appreciation of society’s evolutionary and ecological context. To cite only a sample of such forerunners:

Cleric and economist Thomas Robert Malthus (1766–1834) famously framed the conversation about human population growth, the carrying capacity of natural systems, and social well-being. The terms of that debate have changed, but its essential tensions have endured (Mann 2018).

Geographer and naturalist Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) drew upon his epic exploration of South and Central America (1799–1804) in a lifelong effort to unify fields of knowledge and to comprehend “the chain of connection by which all natural forces are linked together, and made mutually dependent upon each other” (Von Humboldt 1858, p. 23).

Linguist and diplomat George Perkins Marsh (1801–1882) laid foundations for the future conservation movement by detailing the extent of human environmental impacts in his landmark volume Man and Nature: Or, Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action (Marsh 1865).

Geologist and educator Thomas Chrowder Chamberlin (1843–1928) anticipated the Anthropocene in 1883, recognizing “that man is the most important organic agency yet introduced into geological history. …The entire land life is being revolutionized through man’s agency. … A new and profoundly marked era was inaugurated when he became the dominant organic being” (Chamberlin 1883, pp. 299–300).

Returning to these and other precursors to contemporary socio-ecological systems analysis allows us to follow history’s braided stream across two centuries of sustainability thinking. One primary channel, Malthusianism, flows from Malthus himself through Marsh to William Vogt, Fairfield Osborn, Paul Ehrlich, Garrett Hardin, and others (Robertson 2012). It posits a bounded Earth with ultimate limits to its resilience. By contrast, the Cornucopian channel issuing (let us say) from Adam Smith and leading on to Friedrich Hayek, Ayn Rand, and Julian Simon sees an Earth of unbounded abundance, endlessly resilient and productive due to human technological prowess (Jonsson 2014). At issue across time and across ideological divides is the nature of human agency and the assumption of human responsibility.

This is a simple dualism, one that is easy to construct, to read back into the history, and to fall into. But there are also neglected integrators navigating the stream. This third way we can also trace from, say, von Humboldt to Lewis Mumford to Elinor Ostrom and Wendell Berry, marked by their work at the interface of people and nature, where socio-ecological systems thinking finds its own intellectual grounding place. It in this context is that we can appreciate the emergence of resilience as a vital theme in ecology over the last two decades (Olsson et al. 2004; Walker et al. 2004). As resilience theory advanced over this period, others have worked to put its principles into practice on the land through such varied frameworks as ecosystem management, community-based conservation, adaptive management, and ecosystem services (among others) (Meffe et al. 2012). This striving for constructive interdisciplinary approaches has also yielded a bounty of hybrid academic fields, from ecological economics and environmental history to conservation biology and environmental ethics. In these and other bridging fields, scholars and scientists seek systemic solutions to wicked problems.

The same motivation to highlight connections within socio-ecological systems has found expression in the larger culture and in popular political movements. It echoes in the words of Martin Luther King, speaking in 1967:

…All life is inter-related. …We’re caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. …This is the inter-related structure of reality (King 1967).

It resonated in US Senator Gaylord Nelson’s speeches on the first Earth Day in 1970:

Our goal is not just an environment of clean air and water and scenic beauty. The objective is an environment of decency, quality and mutual respect for all human beings and all living creatures (Nelson 1970).

More recently, it finds voice in concepts and sources as varied as Ostrom’s principles for governing common-pool resources (1990), the Earth Charter (2000), and Pope Francis’ integral ecology (2015). The reign of atomism and reductionism within social and ecological systems is tenacious. However, it is not unchallenged.

4 Aldo Leopold and the land ethic in historical context

This brief foray into history allows us to see Aldo Leopold in context, as a transitional figure in the development of the socio-ecological perspective. He was not the first to grasp the “inescapable network of mutuality” in socio-ecological systems nor, obviously, would he be the last. There are aspects of his language, thought, and science that show signs of age after 70 years (Callicott 2002). However, there are reasons we return to Leopold (and other key historical figures). New insights into history constantly emerge in response to new realities. These figures also remind us not to accept uncritically the narrative that sustainability, resilience, and linked socio-ecological systems are entirely new concepts. Because these roots predate the modern environmental movement, they are not freighted with the political weight that the movement (and its detractors) carries. Generations of creative thinkers have sought to integrate social and ecological knowledge, albeit with the blind spots and prejudices that have marked their own times.

Now, however, with a firmer framework of socio-ecological systems to work with, we can read with fresh eyes Leopold’s striving over three decades to define the idea for himself and for his generation of conservation scientists and practitioners. Sampling from his large body of writing, we find Leopold, for example, providing in 1921 the most tangible kind of insight into linked systems:

…[T]he destruction of soil is the most fundamental kind of economic loss which the human race can suffer. …With infinitely expensive works, a ruined watershed may again fill our ditches or turn our mills—if the soil is still there. But if the soil is gone, the loss is absolute and irrevocable” (Meine 2010, p. 188).

By 1933, with the national and global economy collapsed, his view is more expansive:

A harmonious relation to land is more intricate, and of more consequence to civilization, than the historians of its progress seem to realize. Civilization is not, as they often assume, the enslavement of a stable and constant earth. It is a state of mutual and interdependent cooperation between human animals, other animals, plants, and soils, which may be disrupted at any moment by the failure of any of them” (Leopold [1933] 1991, p. 183).

That the new science of ecology was centrally relevant to understanding this “failure” would be underscored through the 1930s. Leopold traveled to Germany in 1935 to study continental approaches to forestry and wildlife management. Disturbed by the political and ecological circumstances he found there, he was compelled to address both the practical and epistemological dilemma:

One of the anomalies of modern ecology is that it is the creation of two groups, each of which seems barely aware of the existence of each other. The one studies the human community, almost as if it were a separate entity, and calls its findings sociology, economics, and history. The other studies the plant and animal community [and] comfortably relegates the hodgepodge of politics to “the liberal arts.” The inevitable fusion of these two lines of thought will perhaps constitute the outstanding advance of the present century (Meine 2010, pp 359–360).

At the end of the decade, he returned to that prediction and also to its practical application:

It seems possible… that [the] prevailing failure of economic self-interest as a motive for better private land use has some connection with the failure of the social and natural sciences to agree with each other, and with the landholder, on a common concept of land….Ecology, as the fusion point of sciences and all the land uses, seems to me the place to look” (Leopold [1939] 1991, pp. 272–273).

Leopold regularly revisited these themes over the last decade of his life, exploring the significance of the “fusion” that he anticipated while absorbing new insights into social and ecological change. In so many cases, he was remarkably prescient, with a rare ability to distill his concern: “Our power to disorganize the land is growing faster than our understanding of it, or our affection for it” (Leopold 1946, p. 216). In other cases, he was of his time and failed to address in any sustained way the social challenges of his own generation, much less to anticipate the ecological and social challenges that we face now. Leopold had little to say directly about climate change, or matters of race, gender, and class disparity. He was not unaware of these issues, and his views were more nuanced than some contemporary critics have assumed (Powell 2015). He did not live long enough to see how the next generation of conservationists would—and would not—confront these questions of intersectionality.

He did, however, leave his readers with statements that read almost as instructions to his own pragmatic self, but that now serve as suggestions to those who would follow his path toward fusion. He cautioned that “We shall never achieve harmony with land, any more than we shall achieve absolute justice or liberty for people. In these higher aspirations, the important thing is not to achieve, but to strive” (Leopold 1953, p. 155). In modern environmental ethics terms, he would thus seem to fall into the deontological camp. Yet, it could be said that he built into the land ethic something of a consequentialist “out,” a call for tangible and ongoing progress in the task. He invited others to follow the path of ethical progress. In “The Land Ethic” he writes, “I have purposely presented the land ethic as a product of social evolution because nothing so important as an ethic is ever ‘written.’ …[It] evolve[s] in the minds of a thinking community” (Leopold 1949, p. 225).

And so, the land ethic has evolved and is evolving beyond Leopold’s own framing, in response to changing social and environmental conditions. Without losing its connections to intimate, particular, and local places, the land ethic has provided the foundation for an expanded Earth ethic that addresses global-scale issues (e.g., Callicott 2013; Moore and Nelson 2011). A movement to define and develop a coherent water ethic has taken hold as the world faces increasingly pressing challenges to freshwater and marine systems (e.g., Auster et al. 2009; Brown 2010; Groenfeldt 2019). Food and agriculture, as the key link between social and ecological systems, has experienced its own new wave of ethical theory and practice (e.g., DeVore 2018; Thompson 2017). In an increasingly urbanized world, it is no longer paradoxical to consider the need for an urban land ethic (e.g., Berry 2013; Kirsch 2013). The environmental justice movement has brought forward essential ethical perspectives from diverse backgrounds and sources (e.g., Driver et al. 1996; Loew 2014; Van Horn and Hausdoerffer 2017).

In all of these directions, and others, the land ethic continues to grow and expand outward to embrace the complexity of the contemporary and future socio-ecological landscape. That process includes the field of socio-ecological practice research. As Berkes et al. (2012) noted, “The connections that Leopold saw between ecosystems and biodiversity on the one hand and human social and political processes on the other, as well as their meeting points in management and policy, are increasingly becoming the foundation of a contemporary science of sustainability….” The articles collected in the special section on “A Sand County Almanac at 70” in this journal are a testament to the vitality of the “social evolution” in which Leopold placed his faith for the continued elaboration of a land ethic.

References

Auster PJ, Fujita R, Kellert SR, Avise J, Campagna C, Cuker B, Dayton P, Heneman B, Kenchington R, Stone G, Notarbartolo di Sciara G (2009) Developing an ocean ethic: science, utility, aesthetics, self-Interest, and different ways of knowing. Conserv Biol 23:233–235

Berkes F, Colding J, Folke C (2000) Rediscovery of traditional ecological knowledge as adaptive management. Ecol Appl 10(5):1251–1262

Berkes F, Doubleday NC, Cumming GS (2012) Aldo Leopold’s land health from a resilience point of view: self-renewal capacity of social–ecological systems. EcoHealth 9(3):278–287

Berry MM (2013) Thinking like a city: grounding social-ecological resilience in an urban land ethic. Idaho Law Rev 50(2):117–152

Brown PG (2010) Water ethics: foundational readings for students and professionals. Island Press, Washington

Callicott JB (2002) From the balance of nature to the flux of nature: the land ethic in a time of change. In: Knight RL, Riedel S (eds) Aldo Leopold and the ecological conscience. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 91–105

Callicott JB (2013) Thinking like a planet: the land ethic and the earth ethic. Oxford University Press, New York

Caradonna JL (2014) Sustainability: a history. Oxford University Press, New York

Chamberlin TC (1883) Geology of Wisconsin, vol 1. Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey, Madison

Cunsolo A, Ellis NR (2018) Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat Clim Change 8:275–281

DeVore B (2018) Wildly successful farming: sustainability and the new agricultural land ethic. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison

Djalali A, Vollaard P (2008) The complex history of sustainability: an index of trends, authors, projects and fiction. https://issuu.com/archis/docs/thecomplexhistoryofsustainability. Accessed 13 Feb 2020

Driver BL, Dustin D, Baltic T, Elsner G, Peterson G (1996) Nature and the human spirit: toward an expanded land management ethic. Venture, State College

Earth Charter Commission (2000) The Earth Charter. https://earthcharter.org/discover/the-earth-charter/. Accessed 15 Feb 2020

Flader SL (1994) Thinking like a mountain: Aldo Leopold and the evolution of an ecological attitude toward deer, wolves, and forests, 1994th edn. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison

Grober U (2012) Sustainability: a cultural history. Green Books, Cambridge

Groenfeldt D (2019) Water ethics: a values approach to solving the water crisis. Routledge, London

Harrabin R (2019) Environment in multiple crises—report. BBC News. 12 Feb 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-47203344. Accessed 13 Feb 2020

Holling CS, Meffe GK (1996) Command and control and the pathology of natural resource management. Conserv Biol 10(2):328–337

Jonsson FA (2014) The origins of Cornucopianism: a preliminary genealogy. Crit Hist Stud 1(1):151–168

Kimmerer R (2011) Restoration and reciprocity: the contributions of traditional ecological knowledge. In: Egan D, Hjerpe EE, Abrams J (eds) Human dimensions of ecological restoration. Island Press, Washington, pp 257–276

King Jr. ML (1967) A Christmas sermon on peace. http://mseffie.com/assignments/invisible_man/Christmas%20Sermon%20on%20Peace.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2020

Kirsch GE (2013) A land ethic for urban dwellers. In: Goggin PN (ed) Environmental rhetoric and ecologies of place. Routledge, London, pp 85–99

Leopold A (1940) Wisconsin wildlife chronology. Wisc Conserv Bull 5(11):8–20

Leopold A (1946) Review of AG Tansley, Our Heritage of Wild Nature. J For 44(3):215–216

Leopold A (1949) A Sand County Almanac and sketches here and there. Oxford University Press, New York

Leopold A (1953) Round River: form the journals of Aldo leopold. Oxford University Press, New York

Leopold A ([1933] 1991) The conservation ethic. In: Flader SL, Callicott JB (eds) The river of the mother of god and other essays. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, pp 181–192

Leopold A ([1935] 1991) Coon valley: an adventure in cooperative conservation. In: Flader SL, Callicott JB (eds) The river of the mother of god and other essays. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, pp 218–223

Leopold A ([1938] 1991) Engineering and conservation. In: Flader SL, Callicott JB (eds) The river of the mother of god and other essays. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, pp 249–254

Leopold A ([1939] 1991) A biotic view of land. In: Flader SL, Callicott JB (eds) The river of the mother of god and other essays. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, pp 266–273

Leopold A ([1942] 1991) The role of wildlife in a liberal education. In: Flader SL, Callicott JB (eds) The river of the mother of god and other essays. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, pp 301–305

Leopold A ([1947] 1991) The ecological conscience. In: Flader SL, Callicott JB (eds) The river of the mother of god and other essays. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, pp 338–346

Loew P (2014) Seventh generation earth ethics: native voices of Wisconsin. Wisconsin Historical Society, Madison

Mann CC (2018) The wizard and the prophet: two remarkable scientists and their dueling visions to shape tomorrow’s world. Knopf, New York

Marsh GP (1865) Man and nature: or, physical geography as modified by human action. Charles Scribner, New York

Meffe G, Nielsen L, Knight RL, Schenborn D (2012) Ecosystem management: adaptive, community-based conservation. Island Press, Washington DC

Meine C (1987) Building “The Land Ethic”. In: Callicott B (ed) Companion to A Sand County Almanac. University of Wisconsin press, Madison

Meine C (2004) The secret Leopold. In: Meine C (ed) Correction lines: essays on land, Leopold, and conservation. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, pp 161–183

Meine C (2010) Aldo Leopold: his life and work, 2010th edn. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison

Meine C (2020) The crucible of conservation: land, science, community, and the Wisconsin idea. In Goldberg C (ed) Renewing the Wisconsin idea. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison

Moore KD, Nelson MP (eds) (2011) Moral ground: ethical action for a planet in peril. Trinity University Press, San Antonio

Nelson G (1970) Partial text for Senator Gaylord Nelson, Denver, Colo, April 22. http://www.nelsonearthday.net/docs/nelson_26-18_ED_denver_speech_notes.pdf. Accessed 15 Feb 2020

Norton BG (2015) Sustainable values, sustainable change: a guide to environmental decision making. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Olsson P, Folke C, Berkes F (2004) Adaptive comanagement for building resilience in social-ecological systems. Environ Manag 34(1):75–90

Ostrom E (1990) Governing the commons: the evolution of institutions for collective action. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Francis P (2015) Laudato Si’: on care for our common home. http://w2.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/encyclicals/documents/papa-francesco_20150524_enciclica-laudato-si.html. Accessed 6 Mar 2020

Powell MA (2015) Pestered with inhabitants: aldo Leopold, William Vogt, and more trouble with wilderness. Pac Hist Rev 84(2):195–226

Reyers B, Folke C, Moore ML, Biggs R, Galaz V (2018) Social-ecological systems insights for navigating the dynamics of the anthropocene. Annu Rev Env Resour 43:267–289

Rittel HW, Webber MM (1973) Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci 4(2):155–169

Robbins P, Moore SA (2013) Ecological anxiety disorder: diagnosing the politics of the Anthropocene. Cult Geogr 20(1):3–19

Robertson T (2012) Total war and the total environment: Fairfield Osborn, William Vogt, and the birth of global ecology. Environ Hist 17(2):336–364

Schoon M, Van der Leeuw S (2015) The shift toward social-ecological systems perspectives: insights into the human-nature relationship. Nat Sci Soc 23(2):166–174

Steffen W, Broadgate W, Deutsch L, Gaffney O, Ludwig C (2015) The trajectory of the anthropocene: the great acceleration. Anthr Rev 2(1):81–98

Thompson PB (2017) The spirit of the soil: agriculture and environmental ethics. Routledge, London

Van Auken P (2020) Towards a fusion of two lines of thought: creating convergence between Aldo Leopold and sociology through the community concept. Socio-Ecol Pract Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-020-00042-7

Van Horn G, Hausdoerffer J (eds) (2017) Wildness: relations of people and place. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Von Humboldt A (1858) Cosmos: a sketch of the physical description of the universe, vol 1. Harper and Brothers, New York

Walker B, Holling CS, Carpenter S, Kinzig A (2004) Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social-ecological systems. Ecol Soc 9(2):5

Wang X (2019) Ecological wisdom as a guide for implementing the precautionary principle. Socio Ecol Pract Res 1(1):25–32

Wang X, Palazzo D, Carper M (2016) Ecological wisdom as an emerging field of scholarly inquiry in urban planning and design. Landsc Urban Plan 155:100–107

Warren JL (2016) Aldo Leopold’s odyssey: rediscovering the author of A Sand County Almanac. Island Press, Washington

Xiang W-N (2014) Doing real and permanent good in landscape and urban planning: ecological wisdom for urban sustainability. Landsc Urban Plan 121:65–69

Xiang W-N (2019) Socio-ecological practice research (SEPR): what does the journal have to offer? Socio Ecol Pract Res 1(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-018-0001-y

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meine, C. From the land to socio-ecological systems: the continuing influence of Aldo Leopold. Socio Ecol Pract Res 2, 31–38 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-020-00044-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-020-00044-5