Abstract

Microwave-assisted solid-state reactions (MSSR) are investigated for their ability to synthesize nanocrystalline BaTiO3 powders at low temperatures. Ba(OH)2·H2O and TiO2·xH2O are, respectively, initial precursors for Ba and Ti. In this study, these precursors were mixed according to their chemical stoichiometry and heated in a temperature range of 100–1000 °C by MSSR. Nanocrystalline BaTiO3 powders having an average size of 26 nm were produced by MSSR, even at 100 °C. The crystallization-related activation energy for the formation of BaTiO3 with the precursors by MSSR was ~ 9.6 kJ/mol, which is less than 1/10 of the value (120 kJ/mol) when the conventional solid-state reaction was applied. The nanostructural and physical features of the MSSR-based powders are compared with those prepared using the conventional solid-state reaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Barium titanate (BaTiO3) is one of the most attractive ferroelectric materials having a ABO3-type perovskite structure. It is extensively used in electronic applications, including as multilayer ceramic capacitors, piezoelectric devices, thermistors with positive temperature coefficients, and semiconducting memory devices [1,2,3]. Various aspects of this material have been widely examined, including its synthesis, sintering, and nanostructural characteristics, to improve the dielectric properties of materials [3,4,5]. In particular, with the advent of nanotechnology, many researchers have investigated advanced synthesis methods to fabricate nano-sized BaTiO3 powders having fine features and high crystallinity. These methods include solid-state reactions, sol–gel processes, and hydrothermal methods [6,7,8].

Solid-state reactions comprise the most common powder manufacturing process, owing to the simplicity of the preparation process and the low cost of source materials. However, the process often requires high temperatures and long reaction times to achieve a complete reaction, and the powders exhibit a large size of more than 500 nm [6, 9]. In contrast, the sol–gel process is usually carried out at low temperatures, which can be used to synthesize nano-sized powders. However, it requires a rather complicated process to produce the sol-type precursors, and the cost of some of its source materials are high. Additionally, the hydrothermal method can be used to synthesize nano-sized powders having good crystallinity. However, this method has some drawbacks, including slow kinetics and a limited reaction temperature below 300 °C because of the limits of the apparatus (e.g., Teflon vessels) [10,11,12].

It has been shown that the application of microwaves has the potential to enhance crystallization and densification kinetics in materials-engineering processes [13,14,15]. Microwave-assisted processes have various advantages, such as high power density, controllable penetration depth, rapid heating, and uniform heating of processed materials [16, 17]. In particular, no thermal conductivity mechanism has been associated with microwave heating, because microwave energy is transferred directly via electromagnetic fields into the materials [18]. Owing to these advantages, hybrid-type sol–gel processes and hydrothermal methods, including microwave irradiation, have been studied to control the crystallization of ceramic powders under various conditions.

Guo et al. [19] reported that 150-nm-sized BaTiO3 powders had been synthesized at a reaction temperature of 80 °C using the microwave-assisted hydrothermal method, which is considered preferable to the conventional hydrothermal method, owing to its time savings, low temperature, and easy application. Sun et al. [20] confirmed that the application of microwaves via the hydrothermal method can control the structural features of synthesized BaTiO3 powders with a short synthesis time. Malghe et al. [21] performed studies on the effects of microwaves when cubic-BaTiO3 powders were synthesized at 500 °C via the sol–gel method, reporting that it contributed to transformation to the tetragonal phase in a microwave field above 700 °C.

There have only been a few studies on the application of microwaves in the formation of ceramic powders via solid-state reactions. Precursors having polar-type bonds provide potential for future application in microwave-assisted solid-state reactions [22, 23]. There has been little investigation on the detailed kinetics relevant to the microwave contribution.

In this study, we investigated how microwave-assisted solid-state reaction (MSSR) can be applied to fabricate nanoscale BaTiO3 powders. The influence of the microwaves on the crystallization and growth of BaTiO3 powders was studied in terms of initial precursors bearing hydroxides and water. The conventional heating-related activation energy was estimated to examine kinetics for the formation of the crystalline BaTiO3 phase when the powders were prepared by MSSR. These results were compared with the values for BaTiO3 powders prepared by conventional solid-state reactions (CSSR).

2 Experimental details

In this study, two types of Ba and Ti precursors were used. Initial precursors for Ba-source included Ba(OH)2·H2O (BH, JUNSEI, Japan) and BaCO3 (BC, JUNSEI, Japan). The initial sources for Ti were TiO2·H2O (TH) and rutile-TiO2 (TO, JUNSEI, Japan). Source TH was an amorphous titania synthesized by adding NH4OH solution in a hydrolyzed TiOCl2 solution. The solution was produced by reacting it with titanium tetrachloride (TiCl4) and ice-cold de-ionized water at 60 °C for 1 h. The initial sources were made by mixing respective Ba and Ti precursors with a Ba/Ti mole ratio of 1:1. These mixed powders are BHTH (BH + TH), BHTO (BH + TO), BCTH (BC + TH), and BCTO (BC + TO). The four types of mixed powders were heat-treated at temperatures ranging from 100 to 1000 °C for 0–60 min via MSSR and CSSR. On the other hand, BaTiO3 powders were also prepared by hydrothermal synthesis to compare structural features with those of the powders prepared by MSSR method. Barium hydroxide octahydrate (Ba(OH)2·8H2O) and TH were used as source materials for Ba and Ti, respectively. Details of the hydrothermal process are listed in Ref. [24].

MSSR and CSSR processes were carried out at heating rates of 100 °C/min and 5 °C/min, respectively, and the samples were cooled naturally. The processing temperature was measured using a thermocouple placed near the sample within the hot zone in the furnace. The microwave heating furnace (Unicera Co., UMF-04), having a monomode reactor, was operated at a microwave frequency of 2.45 GHz and a power of 2 kW. The temperature was controlled using a micro-time slicing method of the microwave power. Conventional heating, however, was carried out with a power of 4 kW in an electrical furnace.

The crystallization and nanostructural features of BaTiO3 powders were examined using X-ray diffraction (XRD; Rigaku, Multiflex 3 kW) using a Cu Kα line (λ = 1.5406 Å). A scan step size and scan speed were set to be 0.02° and 2°/min, respectively. The variation in nanocrystallite size (D) of the powders was measured by examining the XRD results using Scherrer’s equation [25]:

where λ is the wavelength of the X-ray, B is the full width at half maximum (FWHM), and θ is the angle of the diffracted peak. To estimate the conventional heating-related activation energy for the formation of crystalline BaTiO3, isothermal heat-treatments were carried out for 0+, 10, and 60 min at 100–400 °C for MSSR and 600–900 °C for CSSR. Here 0+ stands for the heat-treatment in which the sample was cooled immediately after the holding temperature was reached. The kinetics of the isothermal reaction for the formation of BaTiO3 phase was estimated based on the Arrhenius method. Fourier transform Raman (FT-Raman; Bruker, RFS-100/S) was used to estimate the relative tetragonal fraction of the BaTiO3 powders. The 1064-nm line of a Nd-YAG laser was used, and the applied power was set to be 20 mW. The morphological features were investigated using high-resolution scanning electron microscopy (HR-SEM; Hitachi, SU-8010). All images were obtained in the secondary electron mode, and the accelerating voltage was 15 kV.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Synthesis of BaTiO3 powders

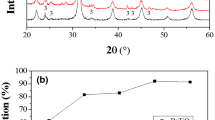

In Fig. 1, the XRD patterns of the powders prepared using BHTH by the MSSR (Fig. 1a) and CSSR (Fig. 1b) methods for 60 min are illustrated. The presence and variation in nanocrystallite size of the BaTiO3 phase were measured from the powders in terms of preparation temperature. Figure 1a shows that the BaTiO3 phase was formed even at 100 °C by MSSR, and the intensity of the peaks related to the BaTiO3 structure increased steadily to ~ 600 °C with increasing reaction temperatures. A small fraction of BaCO3 was noticed under the preparation conditions. It was also noticed that the BaTiO3 and Ba2TiO4 phases co-existed when the temperature reached 600 °C.

XRD patterns of powders prepared with BHTH, synthesized at (1) 100 °C, (2) 200 °C, (3) 300 °C, (4) 400 °C, (5) 500 °C, and (6) 600 °C for 60 min by a MSSR and (1) 600 °C, (2) 700 °C, (3) 800 °C, (4) 900 °C, and (5) 1000 °C for 60 min by b CSSR. Variation in the FWHM of the (101) peaks and nanocrystallite sizes of the BaTiO3 powders prepared with BHTH by c MSSR and d CSSR

In contrast, for powders prepared via CSSR, as shown in Fig. 1b, BaTiO3 phases started to form at ~ 600 °C. BaCO3 phases were dominantly present at this temperature. The BaTiO3 phase was produced at temperatures higher than 600 °C. As a result, in the temperature range of 700–1000 °C, BaTiO3 phase existed dominantly. Figure 1c, d show the variation in the nanocrystallite size of the BaTiO3 powders prepared using BHTH by MSSR and CSSR methods. The FWHM of diffracted peaks (101) is also illustrated in the figure. The nanocrystallite size of the powders synthesized at 100 °C by MSSR was 16 nm, and the size gradually increased to 27 nm with increasing synthesis temperature up to 600 °C. The value of FWHM gradually varied between 0.415 and 0.307 with temperature. On the other hand, in case of the powders prepared by the CSSR method, the nanocrystallite size increased from 42 to 58 nm at the reaction temperature ranging from 700 to 1000 °C. The value of FWHM gradually varied from 0.205 to 0.141 with temperature. To see the difference in how the precursors (e.g., BHTH) with hydroxide and/or water behave compared with those without polar-type bonds, BHTH, BHTO, BCTH, and BCTO were reacted at 400 °C for 60 min via MSSR.

Figure 2 shows the XRD results of the powders having the four different precursors. The BaTiO3 phase was only produced in powders prepared with BHTH, and a small fraction of the BaCO3 phase was observed in the products. The nanocrystallite size of the BaTiO3 structure was approximately 20 nm. In contrast, the powders prepared with BHTO exhibited BaCO3 and rutile-TiO2 phases with a little Ba2TiO4 phase. The powders synthesized using BCTH and BCTO showed only BaCO3 and TiO2 structures, indicating that no reaction took place between the Ba and Ti sources. The TiO2 included anatase and rutile phases.

When BH reacted with TH or TO, new compounds such as BaTiO3 and Ba2TiO4 phases were produced by the reaction between Ba and Ti ions, while a BaCO3 phase was also produced as a by-product. The presence of BaCO3 is likely to be attributed to the reaction of Ba ions with CO2 in air. On the other hand, when the Ba source material was of BaCO3 (BC), Ba and Ti ions reacted to a little degree at this temperature regardless of the type of Ti precursors. Instead, the phase transition related to the TiO2 structure occurred so that some of the source rutile-type phases became an anatase phase [26].

In our experiments, for BH, Ba ions were bonded with hydroxide and/or the water was placed on the surface of Ba ions. For TH, Ti–O was chemically bonded with di-hydrate placed on the surface of Ti ions. Zhao et al. [27] reported that the initial sources having water and/or hydroxide had high surface energies, resulting in high reactivity. As shown in Fig. 3, the initial sources with water and/or hydroxide molecules had higher free energy at 100 °C (state I) than that at room temperature (state II). The initial sources without any water and/or hydroxide (e.g., BaCO3 and TiO2) were expected to have the lowest free energy at room temperature (state III) among the source materials. Comparisons were made with respect to the transition states for the formation of BaTiO3 in the figure. Therefore, the initial sources having water and/or hydroxide were expected to require a smaller energy for the formation of BaTiO3.

Free energy states of initial sources with or without water and hydroxides. Schematic of the effective energy barrier for the formation of BaTiO3. The barrier can be overcome via the application of microwave and thermal energy. States I and II represent free energies of reactants with water/hydroxide with the additional thermal energies of 100 °C and room temperature, respectively. State III indicates free energy of reactants without water/hydroxide at room temperature

Initial sources having additional polar dipoles (e.g., water (H2O) and hydroxide (OH-)) were expected to have molecular oscillations under microwave irradiation [22, 28, 29]. Consequently, microwave-related energy is absorbed effectively in the materials, and it can decrease the conventional heating-related thermal energy barrier for the formation of a BaTiO3 structure. In Fig. 3, the activated state was set for the formation of BaTiO3, and, as a result, the initial source materials having water and/or hydroxide could overcome the energy barrier (ΔEa,1), even at 100 °C with the assistance of microwave (in Fig. 1a) energy. Here, the conventional heating-related energy at this temperature is represented by ΔE100 °C, and the energy, which was conceived from the electromagnetic field, is regarded to be approximately ΔEa,1. These approximated values were made based on the lowest temperature at which the formation of BaTiO3 was observed in Fig. 1a. On the contrary, in case of initial sources without water and hydroxide, the energy barrier of ΔEa,3 was higher than that of ΔEa,1, Therefore, the contribution from the microwave was negligible for overcoming ΔEa,3.

Similarly, TO had a lower reactivity than did TH by ΔEwater/hydroxide. Owing to the low reactivity and the lack of additional polar dipoles of TO, BHTO had insufficient energy to overcome the activation energy for the formation of BaTiO3, even at a reaction temperature of 400 °C (in Fig. 2).

3.2 Estimation of the crystallization activation energy for the formation of BaTiO3 phase

The microwave effect on the crystallization of the BaTiO3 structure was quantitatively investigated by calculating the conventional heating-related activation energy for the formation of the BaTiO3 phase. The crystallization kinetics can be estimated in terms of nanocrystallite size by the following equation [30]:

where G is the crystallite size of the BaTiO3 structure, depending on the reaction time (t). G0 is the initial size of crystallite for a reaction time of 0 + min (t0), n is the crystallite growth exponent related to crystallization mechanism, and k is the reaction rate constant. The exponent (n) can be measured using a best-fit method from the logarithm of Eq. (2), as shown in the inset of Fig. 4a, b [31]. The values of n were determined to be 3.8 and 2.4 for the formation of BaTiO3 phase using MSSR and CSSR methods, respectively. It was reported that the n value was significantly associated with the crystallization mechanism [32, 33]. The significant difference in the n values indicates that the growth of BaTiO3 crystal in the MSSR method was dominantly dependent on the diffusion process of the constituents, whereas an interface movement was the determining process when CSSR was applied. More experimental investigation is under way to support the respective crystal-growth processes.

Variations in crystallite size (Dn) of BaTiO3 powders prepared by a MSSR and b CSSR methods are plotted in terms of holding time (t). The powders were synthesized at 100 °C by MSSR and at 700 °C by CSSR, respectively. Crystal growth exponent (n) was evaluated based on the best-fit method, as shown in the insets. Plots of ln k versus 103/T were used to calculate the crystallization activation energy of sample BHTH prepared by c MSSR and d CSSR methods

The conventional heating-related activation energy can be calculated by the Arrhenius equation, as follows:

where k is the reaction rate, k0 is the pre-exponential constant, Q is the activation energy, R is the gas constant, and T is the absolute reaction temperature.

Based on the nanocrystallite size of the BaTiO3 structure, the conventional heating-related activation energy (Q) for the phase formation can be calculated from the slope of the straight line fitted to a plot of ln k versus 1/T, as shown in Fig. 4c, d [34]. Table 1 shows that the value of ln k and the activation energies of BHTH heat-treated by MSSR at temperatures ranging from 100 to 400 °C and by CSSR at temperatures ranging from 700 to 1100 °C were calculated in terms of the reaction times 0+–10 and 10–60 min, respectively. The respective ranges of the temperatures were confirmed to be the temperatures at which the BaTiO3 phase was actively produced from BHTH by MSSR and CSSR (in Fig. 1).

The activation energy for a reaction time of 0+–10 min was ~ 9.6 kJ/mol for BHTH prepared by MSSR, which is far less than that of BHTH prepared by CSSR (120 kJ/mol). The activation energies for BHTH samples prepared by MSSR and CSSR for 10–60 min slightly decreased to 8.3 and 115 kJ/mol, respectively.

There have been few reports about the estimation of the crystallization energy of BaTiO3 based on Ba- and Ti- source materials having hydroxide or water. Therefore, it is not possible to make a direct comparison of our results with other research group’s work. According to Osman [35], the activation energy for the formation of the BaTiO3 phase based on the reaction between BaCO3 and TiO2 at temperatures of 970–1075 °C ranged from 183 to 197 kJ/mol. Additionally, Balaz et al. [36] reported that the activation energy for the formation of the BaTiO3 phase by the reaction between BaCO3 and TiO2 at a temperature of 620 °C was approximately 270 kJ/mol. The values (183 and 270 kJ/mol) for the formation of the crystalline BaTiO3 phase were much higher than 120 kJ/mol obtained in this study by CSSR for 0–10 min.

As in the case of BHTH, the energy barrier (ΔEa,2) was smaller than those (ΔEa,3) of initial sources without water and hydroxide. Thus, the activation energy for the formation of BaTiO3 from BHTH by CSSR in this study was lower than that for the reaction between BaCO3 and TiO2 at a temperature of 620 °C [36]. Additionally, under microwave irradiation, BHTH prepared by MSSR had a significantly lower conventional heating-related activation energy value (9.6 kJ/mol) compared with BHTH prepared by CSSR. This difference indicated that the additional water molecules of the initial sources seemed to bring an excitation energy of ~ 110 kJ/mol to BHTH under microwave irradiation. Consequently, owing to the contribution of the microwave effect on the reaction, BHTH underwent an efficient synthesis process by MSSR resulting in the rapid synthesis of the BaTiO3 phase, even at a low temperature of 100 °C and a short reaction time of less than 1 min.

3.3 Microstructural and physical features of the BaTiO3 powders prepared by various synthesis methods

Figure 5 shows the XRD results obtained from the powders prepared at 100 °C for less than 1 min with BHTH by MSSR and at 180 °C for 6 h by the hydrothermal method. These powders had the same crystal phases of BaTiO3 and BaCO3. These results indicate that the powders prepared by MSSR and hydrothermal methods had a similar crystallinity as that of the BaTiO3 structure, and the powders prepared by MSSR had a lower fraction of the BaCO3 phase than did the powders prepared by the hydrothermal method.

In Fig. 6, SEM images of the BaTiO3 powders prepared with BHTH at 100 °C by MSSR, at 180 °C by the hydrothermal method, and at 600 °C by CSSR were measured to examine the size and shape of the powders. The powders prepared at 100 °C by MSSR have a spherical shape, appearing similar to that of the powders synthesized by the hydrothermal method. The size of the powders prepared by MSSR is ~ 26 nm, whereas that of powders prepared by hydrothermal method is ~ 54 nm. However, in Fig. 6c, the powders prepared by CSSR had an average size of ~ 320 nm, and the surface seemed to be faceted because of the crystal growth at a considerably high temperature (600 °C).

Figure 7 shows the FT-Raman spectra measured from the BaTiO3 powders prepared at 100 °C by MSSR, at 600 °C by CSSR, and at 180 °C by the hydrothermal method. The intensity of the peak obtained from the powders near at 305 cm−1 was compared with the standard tetragonal-phased BaTiO3 powders to estimate the relative tetragonal fraction of the powders [37]. The intensity of the peak was estimated by measuring the area under the peak after setting the baseline. The intensity ratios of the powders prepared by MSSR, CSSR, and the hydrothermal method were approximately 19%, 17%, and 12%, respectively.

4 Conclusions

BaTiO3 powders having an average size of ~ 26 nm were formed at even 100 °C via MSSR. Ba(OH)2·H2O and TiO2·xH2O were used as Ba and Ti source materials, respectively. The crystallization kinetics of the BaTiO3 phase were examined by estimating the conventional heating-related activation energies. The values for the synthesis of BaTiO3 powders from Ba(OH)2·H2O and TiO2·xH2O by MSSR and CSSR were 9.6 and 120 kJ/mol, respectively. This result clearly shows that MSSR was an efficient synthesis process when initial source materials having water and/or hydroxide are used. Their additional polar molecules brought high reactivity under microwave irradiation.

References

Kishi H, Mizuno Y, Chazono H (2003) Base-metal electrode-multilayer ceramic capacitors: past, present and future perspectives. Jpn J Appl Phys 42:1–15

Yang WC, Hu CT, Lin IN (2004) Effect of Y2O3/MgO Co-doping on the electrical properties of base-metal-electroded BaTiO3 materials. J Eur Ceram Soc 24:1479–1483

Kwei GH, Lawson AC, Billinge SJL, Cheong SW (1993) Structures of the ferroelectric phases of barium titanate. J Phys Chem 97:2368–2377

Hu D, Ma H, Tanaka Y, Zhao L, Feng Q (2015) Ferroelectric mesocrystalline BaTiO3/SrTiO3 nanocomposites with enhanced dielectric and piezoelectric responses. Chem Mater 27:4983–4994

Pena MA, Fierro JLG (2001) Chemical structures and performance of perovskite oxides. Chem Rev 101:1981–2017

Manzoor U, Kim DK (2007) Synthesis of nano-sized barium titanate powder by solid-state reaction between barium carbonate and titania. J Mater Sci Technol 23:655–658

Lemoine C, Gilbert B, Michaux B, Pirard JP, Lecloux A (1994) Synthesis of barium titanate by the sol–gel process. J Non-Cryst Solids 175:1–13

Lu SW, Lee BI, Wang ZL, Samuels WD (2000) Hydrothermal synthesis and structural characterization of BaTiO3 nanocrystals. J Cryst Growth 219:269–276

Buscaglia MT, Bassoli M, Buscaglia V, Alessio R (2005) Solid-state synthesis of ultrafine BaTiO3 powders from nanocrystalline BaCO3 and TiO2. J Am Ceram Soc 88:2374–2379

Boulos M, Guillemet-Fritsch S, Mathieu F, Durand B, Lebey T, Bley V (2005) Hydrothermal synthesis of nanosized BaTiO3 powders and dielectric properties of corresponding ceramics. Solid State Ion 176:1301–1309

Shandilya M, Rai R, Singh J (2016) Review: hydrothermal technology for smart materials. Adv Appl Ceram 115:354–376

Komarneni S (2003) Nanophase materials by hydrothermal, microwave-hydrothermal and microwave-solvothermal methods. Curr Sci 85:1730–1734

Brosnan KH, Messing GL, Agrawal DK (2003) Microwave sintering of alumina at 2.45 GHz. J Am Ceram Soc 86:1307–1312

Srilakshmi C, Saraf R, Prashanth V, Rao GM, Shivakumara C (2016) Structure and catalytic activity of Cr-doped BaTiO3 nanocatalysts synthesized by conventional oxalate and microwave assisted hydrothermal methods. Inorg Chem 55:4795–4805

Clark DE, Folz DC, West JK (2000) Processing materials with microwave energy. Mater Sci Eng 287:153–158

Stein DF (1994) Microwave processing of materials. National Academies Press, Washington

Booske JH, Cooper RF, Freeman SA (1997) Microwave enhanced reaction kinetics in ceramics. Mater Res Innov 1:77–84

Katz JD (1992) Microwave sintering of ceramics. Annu Rev Mater Sci 22:153–170

Guo L, Luo H, Gao J, Guo L, Yang J (2006) Microwave hydrothermal synthesis of barium titanate powders. Mater Lett 60:3011–3014

Sun W, Li C, Li J, Liu W (2006) Microwave-hydrothermal synthesis of teteragonal BaTiO3 under various conditions. Mater Chem Phys 97:481–487

Malghe YS, Gurjar AV, Dharwadkar SR (2004) Synthesis of BaTiO3 powder from barium titanyl oxalate (BTO) precursor employing microwave heating technique. Bull Mater Sci 27:217–220

Tsakalakos T, Ovid`ko IA, Vasudevan AK (2012) Nanostructures: synthesis, functional properties and applications. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht

Gabriel C, Gabriel S, Grant EH, Halstead BSJ, Mingos DMP (1998) Dielectric parameters relevant to microwave dielectric heating. Chem Soc Rev 27:213–223

Moon SM, Lee CM, Cho NH (2006) Structural features of nanoscale BaTiO3 powders prepared by hydro-thermal synthesis. J Electroceram 17:841–845

Patterson A (1939) The Scherrer formular for X-ray particle size determination. Phys Rev 56:978–982

Lee SI, Randall CA (2007) Modified phase diagram for the barium oxide-titanium dioxide system for the ferroelectric barium titanate. J Am Ceram Soc 90:2589–2594

Zhao G, Schwartz Z, Wieland M, Rupp F, Geis-Gerstorfer J, Cochran DL, Boyan BD (2005) High surface energy enhances cell response to titanium substrate microstructure. J Biomed Mater Res A 74:49–58

Bilecka I, Niederberger M (2010) Microwave chemistry for inorganic nanomaterials synthesis. Nanoscale 2:1358–1374

Kappe CO (2004) Controlled microwave heating in modern organic synthesis. Angew Chem Int Ed 43:6250–6284

Avrami M (1939) Kinetics of phase change I. J Chem Phys 7:1103–1112

Muthuramalingam M, Jain Ruth DE, Veera Gajendra Babu M, Ponpandian N, Mangalaraj D, Sundarakannan B (2016) Isothermal grain growth and effect of grain size on piezoelectric constant of Na 0.5 Bi 0.5 TiO 3 ceramics. Scr Mater 112:58–61

Coble RL (1961) Sintering crystalline solids. II. Experimental test of diffusion models in powder compacts. J Appl Phys 32:793–799

Iverson RB, Reif R (1987) Recrystallization of amorphized polycrystalline silicon films on SiO2: temperature dependence of the crystallization parameters. J Appl Phys 62:1675–1681

Chen CS, Chen PY, Chou CC, Chen CS (2012) Microwave sintering and grain growth behavior of nano-grained BaTiO3 materials. Ceram Int 38:S117–S120

Osman KI (2011) Synthesis and Characterization of BaTiO3 Ferroelectric Material. PhD Thesis, Cairo University, Egypt

Balaz P, Plesingerova B (2000) Thermal properties of mechanochemically pretreated precursors of BaTiO3 synthesis. J Therm Anal Calorim 59:1017–1021

Preda L, Courselle L, Despax B, Bandet J, Ianculescu A (2001) Structural characteristics of RF-sputtered BaTiO3 thin films. Thin Solid Film 389:43–50

Funding

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2016R1D1A1B03934622).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yun, HS., Yun, BG., Lee, HM. et al. Low-temperature synthesis of nanoscale BaTiO3 powders via microwave-assisted solid-state reaction. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1366 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1398-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1398-z