Abstract

This research continues the advances in applied positive psychology by measuring and exploring the factors which contribute to the happiness among people living in Prince Edward Island (PEI), Canada. This research provides a province-wide account of subjective well-being (SWB), which is defined as a person’s cognitive and affective evaluation of his or her life, by answering the questions: What is the measurable level of well-being of individuals in PEI? What are the relationships between community factors and components of well-being in PEI? Which quality of life factors most influence individual’s emotions and life satisfaction in PEI? Participation was voluntary, anonymous, and included just over 1% of the adult population of residents (n = 1381). Data was collected online between October and November 2020. Demographic variables were collected and analyzed using variance of mean scores from three self-reported well-being measures, Satisfaction with Life Scale, Positive and Negative Effect Schedule, and the World Health Organization’s (brief) Quality of Life Scale. Regression analysis was used to investigate contributions to well-being. Findings uncovered inequity in well-being among minority populations including, LGBT, gender diverse, Indigenous, disabled, and those living under the poverty line. This study provides a deeper understanding that Islanders view psychological health and healthy environment as important aspects of quality of life influencing their well-being. Results build on existing theories on the influence of income, age, and education have on well-being. Finally, the research provides a starting point and methodology for the continuous measurement and tracking of both the affective and cognitive accounts of well-being on PEI, or in other communities, provinces, or islands. This research provides insight into happiness as an indicator of how our society is performing and adds momentum towards the adoption of sustainable development goals, such as national happiness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

This research article is laid out in six sections. "Introduction" section provides an introduction with definitions of subjective well-being and how it is understood in this study. It includes a rational for why this research is relevant and provides a background of advances in current research. "Methods" section reviews the process and methods by which the research followed, this includes the recruitment of participants, data collection, analysis, and ethical considerations. "Results" section provides statistically significant findings of results, including only those with medium and high effect sizes. "Discussion" section discusses why these findings are important and provides recommendations for future research. "Conclusion" section summarizes the research. This article refers to many of its appendixes, which include recruitment material, participant consent forms, measurement surveys, and ethical approvals. Refer to these appendixes throughout the article.

Introduction

Definitions, Aims & Rationale for Research

Individuals determine whether their own lives are worthwhile and meaningful, making the concept of well-being inherently subjective. As a result, researchers commonly use the terms happiness and subjective well-being synonymously (Armenta et al., 2015). Subjective well-being (SWB) is defined as the evaluation of the quality of one’s life and includes an affective and a cognitive component (Diener et al., 1999). The affective component refers to the frequency of experienced emotions, either positive or negative. Research shows that an individual with high levels of subjective well-being reports heightened levels of positive emotions and low levels of negative emotions (Diener et al., 1999). The cognitive component of SWB is comprised of overall life satisfaction, as well as one’s evaluation of multiple quality of life domains, such as physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and the environment in which they live (Armenta et al., 2015). There is no guideline for how life should be experienced. When individuals reflect on their lives, they compare them with the standards they have for a ‘good life’ (Diener, 2009). As research in well-being progresses, scholars suggest that types of SWB are separable and distinct. This research will explore if distinct aspects of perceived quality of life have different associations with components of subjective well-being (Lucas et al., 1996). As governments attempt to improve quality of life, based on both enhancing well-being and fulfilling societal needs, it is possible that the fulfillment of certain needs are more strongly associated with some types of ‘happiness’ than with others. This research explores the suggestion that ‘identifying which societal factors most strongly influence SWB will help to inform programs and policies that influence the subjective quality of life’ (Tay et al., 2015, p. 849). Well-being measures, such as satisfaction with life have been included in Statistics Canada’s General Societal Survey (GSS) over the past 25 years. Cognitive aspects of well-being, such as satisfaction with life, provide important data. It can be argued that the GSS does not accurately measure happiness in a fulsome way, as it excludes the affective components of subjective well-being, which are societal levels of pleasant and negative emotions. Life evaluation, positive feelings, and negative feelings form clearly separable factors when collected in self-reported sampling (Lucas et al., 1996). The World Happiness Report recommends countries and communities should ‘begin the systematic measurement of happiness itself, in both its affective and evaluative dimensions’ (Sachs et al., 2018, p. 8). In Canada, there appear to be research opportunities in collecting and analyzing data that scientifically measures the affective components, in addition to cognitive components, of well-being. Tay et al. (2015 p. 849) recommend, through this ‘systematic measuring of SWB at both a provincial and community level, continued research can offer a way for policymakers to track the effectiveness of government initiatives and investments regarding the happiness of citizens.’

This research focuses on Canada’s smallest province, Prince Edward Island (PEI), which has a 2020 population of 156,947 (PEI Statistics Bureau, 2021). The aim of this research is to evaluate the happiness of PEI at the community level and as a whole. The research aims to identify groups and regions where citizens are flourishing and struggling. This research also reviews the casual effect and associations of the four quality of life domains; physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and healthy environment, have on both cognitive and affective well-being. The rationale for this research is to continue the advances in applied positive psychology by creating new and replicable opportunities for researchers to provide useful information to policy makers through accounts of well-being (Diener et al., 2015). By measuring and tracking the subjective sense of happiness and life satisfaction on PEI, we can improve societal conditions and maximize the fulfilment and human potential of its residents (Diener et al., 2018). The 2019 World Happiness Report put forward that strong data collection on well-being can help policymakers move towards sustainable development goals, such as national happiness (Helliwell et al., 2019).

Review of Literature

This section explores the context and background of subjective well-being research. In addition, it provides hypotheses based on current literature. In recent years, the study of happiness and subjective well-being (SWB) has gained popularity by both psychologists, social scientists, and more recently, economists. Research by Diener and Seligman (2004) explores how the subjective experience of happiness is an intrinsically valuable personal goal pursued by all individuals. More basic and fundamental than money. A survey of 41 counties revealed that individuals on average rated life satisfaction and happiness close to ‘extraordinarily important and valuable’ (Diener et al., 1998). There is evidence that ‘happiness is a top priority for societies and individuals, making SWB a highly valuable social indicator when predicting quality of life’ (Tay et al., 2015 p. 849). SWB measures are now being applied and advocated for in multiple contexts for tracking society’s quality of life over time (Tay et al., 2015). For example, research on the benefits of SWB shows a wide range of valued outcomes, such as health and longevity (Diener & Chan, 2011), strong social relationships (Moore et al., 2018), success (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005), work productivity (Tenney et al., 2016), and resilience (Fredrickson et al., 2003). Globally, studies by Diener and Diener (2009) and Oishi et al. (2009), reported that self-esteem, income, financial satisfaction, family satisfaction and job satisfaction are positively associated with SWB in most countries, making it a valuable pursuit around the world.

Psychological research proposes that there are universal needs that create a feeling of well-being (Ryff & Keyes, 1995)are tolerated and embraced. Those universal needs are physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and healthy environments, although it is still unclear to what extent these needs will influence an individual’s well-being. It is plausible that the needs might have different associations with distinct types of SWB (Diener et al., 2010), something this research will explore. Furthermore, it is suggested that ‘attempts to improve quality of life should be based on both fulfilling needs and enhancing SWB’ (Tay & Diener, 2011 p. 363).

Theories as to how well-being is created paired with methods of measurement have enabled researchers with the capabilities to scientifically explore well-being. Given its subjective nature, measuring happiness gives privilege to one’s personal evaluation and experiences. Worldwide, self-reported rating scales have become the leading method to measure SWB (Diener et al., 2018). Much research has been done to show the validity and reliability of self-reported measures of happiness. For instance, Larsen et al. (1985) demonstrate the strong correlation of self-reported measures with theoretical constructs, and Diener et al. (1985) has shown the reliability over time. Research has demonstrated that individual results from the self-reported surveys show substantial convergence with non-self-reported measures, such as reports of family and friends (Schneider & Schimmack, 2009).

As the ability to measure and enhance levels of well-being develops, theories conflict about whether levels of well-being can be altered in the long term. Headey and Wearing (1992) stated that life events, both positive and negative, may influence an individual’s short-term level of SWB, but people soon adapt to these new circumstances and their level of well-being returns to a similar level reported prior to their change in circumstances. This adaptation is known as set-point theory, in which individuals have their own biologically determined level of well-being to which they return over time. This raises the question, if we adapt back to our original set-point, is it possible to change an individual’s level of well-being in the long term? Research on pairs of identical twins suggests that happiness can be changed within ‘wide limits’ despite a genetic component of underlying stability (Lykken, 1999). A recent analysis by Bartels (2015 p. 154), indicates genetic factors contributing to set-point theory does contribute significantly but explain only about 35% of the variance in subjective well-being. Studies on immigrants support the ability to change our levels of well-being in the long term (Helliwell et al., 2016). For instance, a study found that new immigrants to Canada change from their original levels of satisfaction with life from the previous nation to a higher level of satisfaction in the long term, in Canada (Frank et al., 2016). This gives evidence that set-point theory cannot explain substantial societal differences in SWB. Although there may be individual propensities towards levels of happiness, the environment and circumstances can influence SWB so that there is not a firm set-point for everyone (Helliwell et al., 2016). Although individuals do tend to return to their original levels of well-being, there is convincing evidence to suggest that individuals and societies have much larger control over levels of well-being than once believed. There is sufficient evidence that SWB is a valued pursuit that is measurable, malleable and can have lasting changes over time (Tay & Kuykendall, 2013). This gives encouragement to policymakers, who, through societal changes, want to increase the public’s well-being. As global interest in subjective well-being continues to grow, research has moved from smaller studies toward larger, national samples, from around the world (Diener et al., 2018). This allows for a wide scope of generalized findings. SWB data has become adopted by several countries and international organizations to assess and inform public policy. In 2000, and again in 2015, it is suggested that national accounts of SWB be created to help inform policy decisions beyond the economic indicators (Diener et al., 2015).

This current research gives three applications of SWB measures. First, by enhancing clarity of the links between subjective quality of life and specific economic and social indicators. Secondly, it supports the suggestion that ‘economic policies can enhance society SWB via several different pathways’ (Tay et al., 2015 p. 847). Thirdly, economic researchers propose using the data from collections of self-reports of SWB as an indicator of how society is performing (Dolan & Metcalfe, 2012).

Measurements of happiness have valuable potential, however, there are shortcomings and limitations. Firstly, Deaton and Stone (2016) challenge the accuracy of the self-reported surveys and speculate that the context in which the questions are asked can influence responses to subsequent questions, affecting the overall results of the survey. Individuals who experience negative emotions prior to answering survey questions can lower their own self-reported well-being. Secondly, when creating a national account of well-being there are limitations to reaching a wholesome population of participants, which can influence results. Research shows that there are differences in well-being responses from easy-to-reach respondents to hard-to-reach respondents (Heffetz & Rabin, 2013). This suggests putting greater weight on data collection from hard-to-reach respondents will create a more fulsome picture of overall well-being.

Based on recent happiness research, below are factors hypothesized to show a similar effect in this current study of well-being on Prince Edward Island:

-

Age: Recent research has found that age as compared to life satisfaction is typically U-shaped (Graham & Pozuelo, 2017). Their finding showed that people in their 20’s and in their 70’s are more satisfied with their lives in general than those in their late 40’s and early 50’s.

-

Immigration: A recent study conducted in PEI, found that the same proportion of immigrants and Canadian-born viewed their quality of life as being excellent/very good, suggesting only subtle differences in well-being between the two groups (Randall et al., 2014). Additionally, national research shows many immigrant groups do not differ significantly from the Canadian-born in average life satisfaction (Frank et al., 2016).

-

Life Circumstances: Life circumstances, such as having mental or psychical disabilities are often shown to be associated with lasting lower levels of well-being (Lucas, 2007), and individuals with disabilities often report feeling isolated from the communities in which they reside (Hedberg & Skärsäter, 2009).

-

Sexual Orientation & Gender Identity: Research in Ireland found members of the LGBT community report lower levels of happiness and mental health through difficulties around self-acceptance, and social and peer support (de Vries et al., 2020). Additionally, research in the UK found that transgendered individuals experienced significantly higher psychopathology, and lower quality of life and life satisfaction when compared to a control group (Davey et al., 2014). The Gallop World Poll provides evidence from global research that women are either happier than men or that there is no significant difference between women and men (Zweig, 2015).

-

Indigenous Communities: Researchers remind us how Indigenous peoples in Canada (such as Mi’kmaq and Abegweit in PEI) often experience a greater burden of poor health and wellness relative to non-Indigenous Canadians due to a legacy of colonialism and racism (Schill et al., 2019).

-

Income: Research has shown that although income is positively related to SWB, to a point, it depends on what aspects of well-being are being measured. It appears income more strongly influences an individual’s cognitive components of life evaluation but has less effect on the affective components of an individual’s positive/negative feelings (Kahneman & Deaton, 2010). Current research reveals that, globally, income serves to fulfil well-being needs to a point, but ceilings for both individual’s evaluation of life and emotional well-being (Jebb et al., 2018).

-

Levels of Education: Research showed people with higher education are more likely to report higher levels of cognitive and affective SWB (Nikolaev, 2018).

-

Regional Differences: When assessing how residents in PEI evaluate well-being, local research shows rural PEI communities tend to be close-knit with high social capital and that at least some Islanders place a high degree of importance on community social well-being as a contributor to quality of life (LeVangie et al., 2011). Research, with appropriate data, on PEI community well-being, is encouraged. Similar research in a north shore PEI community suggests that many residents are engaged citizens, with an acute sense of place, that highly value beaches, riverbanks, and coastal properties (Novaczek et al., 2011). Evidence also suggests that many (north shore) residents care passionately about the social, cultural, economic, and environmental well-being of the Island (LeVangie et al., 2011). Global research into islands and ‘islandness’ gives insight into island well-being and states that “islands create a sense of a place closer to the natural world and to neighbours, who are tolerated and embraced” (Conkling, 2007 p.200).

Though well-being measurements on PEI should follow these same trends, this study will shed more light on how local groups and the community evaluate their happiness. The 2018 World Happiness Report (Sachs et al., 2018) put forward that asking people whether they are happy or satisfied with their lives offers valuable information about society.

This research conceptualizes happiness as people’s evaluations of their own lives. It is believed to be an important phenomenon and considered an aspect of a good life (Diener et al., 1999). The ontological belief of this study is that there is a single perceived reality that individuals have of their well-being and of their quality of life. Advances in the study of well-being have ‘turned the attention and focused not on defining what a good life ought to be, but rather on the factors that lead people to subjectively experience their lives as worthwhile and rewarding’ (Diener et al., 2018 p. 253). This research on well-being takes an objective approach with the belief that there is a single reality where the elements contributing to life satisfaction are determined by respondents rather than by the researcher (Diener, 2009). This research will not prejudge what people will consider a good life for themselves, but instead, will ‘rely on the judgement of respondents themselves to provide, based on whatever criteria the research participants deem to be most important’ (Diener et al., 2018 p. 253). The epistemology of this research takes an empirical view that we can gain knowledge of people’s own experiences. By collecting data on how individuals and communities experience well-being, we can observe the factors that lead people to perceive their lives in positive versus negative ways.

This research attempts to fill a knowledge gap and gain a deeper understanding of true nature of the human experience and societal well-being on PEI by using positivist exploration and quantitative measurement reasoning. Further, this research takes a post-positivist perspective, in that, although the aim of this study is to measure subjective well-being, it is recognized that it is only an approximation and that how we define and measure happiness is imperfect. Through these paradigms, this research will attempt to answer the following questions: What is the measurable level of well-being of individuals in PEI? What is the relationship between community factors and components of well-being in PEI? Which quality of life factors most influence an individual’s emotions and life satisfaction in PEI? Exploring these questions can signal underlying crises or hidden strengths. The findings of the study may suggest a need for change.

Methods

Design

This mixed-methods, positivist, cross-sectional study was designed using four subjective well-being components (Diener et al., 1999), as dependent variables, which include i) overall life satisfaction, measured using Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) ii) perceived quality of life, measured using the World Health Organization’s (brief) Quality of Life Scale (WHOQOL-BREF), which captures four life domains: physical, psychological, social, and environmental, iii) frequency of positive emotions, and iv) frequency of negative emotions, both measured using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) subscales. A qualitative question gave an extra layer of data collection. Detailed demographic information of participants was collected, including age, gender identity and sexual orientation, immigration status, life circumstances, income, ethnicity, education, and region of the province lived in, which provided focused and segmented independent variable to analyze. All data was collected online during October and November 2020, with participation time of approximately 10 minutes. The analysis allowed for generalizations of communities that experience significantly different levels of well-being and explored local characteristics and contributions to well-being on PEI.

Participants

Participants were English-speaking residents of PEI, over the age of 18, who had access to the internet. Participation was completely voluntary and anonymous. Participants (n = 1381) made up over 1.12% of the total adult population of 119,055 (PEI Statistics Bureau, 2021), from the three regions of the province: Kings (n = 156), Queens (n = 898), and Prince County (n = 328), with females making up 83%. Strong participation satisfied conditions to detect large effect sizes in data analysis.

Materials

The measurement of subjective well-being is based on the broad construct that the evaluation of one’s happiness includes both affective and cognitive components (Diener et al., 1999). In 2018, Diener et al. (p.253), put forward that because ‘SWB is not a unitary phenomenon, scientists must study each of the components separately’. In this study, the primary quantitative outcome measured is subjective well-being, which is split into cognitive and affective components, using the following three self-reported scales: Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), World Health Organization’s (brief) quality of life scale (WHOQOL), and the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). All three scales are validated, reliable, and widely used internationally to collect data on well-being. With well-being being experienced differently by everyone, evaluation is extremely subjective in nature. The measures chosen take self-reported surveys and generate large quantitative data. Below are more details of the three self-reported scales used in this quantitative research:

The satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) was used to measure the cognitive judgments of satisfaction individuals have with their life. The inventory consists of 5 Likert scale questions. The participants indicated their level of agreement with statements on a 7-point scale ranging from 1, “strongly disagree” to 5, “strongly agree.” An example item is “In most ways my life is close to my ideal.” Developed by Diener et al. (1985), it has been validated and shows strong reliability with a high Cronbach’s alpha (.87). Scoring is done by finding the sum of the five questions, where scores range from the lowest of 5–9, being extremely dissatisfied, to the highest scores of 31–35 being extremely satisfied. The scale takes approximately 1 minute for participants to compete. (See 25.)

World Health Organization’s (brief) quality of life scale (WHO-QOL) was used to measure a more focused, yet brief, cognitive evaluation of an individual’s quality of life (WHOQOL Groups, 1998). WHO-QOL is a 26-item, (an abbreviated version of the WHO’s more comprehensive 100-item scale), with four domain subscales for physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment. Brevity and ease of surveys were considered when selecting the WHO-QOL (brief) for this study. The multi-dimensional inventory shows strong validity and reliability when compared to standard unidimensional approaches that measure each quality of life domain separately (Wang et al., 2006). The inventory consists of 26 Likert scale questions. The participants indicated their level of agreement with statements on a 5-point scale ranging from 1, “not at all” or “very dissatisfied” to 5, “extremely” or “very satisfied.” Example questions include “how safe do you feel in your daily life?” or “how satisfied are you with your personal relationships?” Domain scores are calculated by finding the sum of the questions pertaining to each domain. The WHO-QOL takes approximately 5 minutes for participance to compete. (See 26.)

Positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS) was used to measure the affective components of well-being, which involve the frequency of emotions, both pleasant and unpleasant, that individuals experience. The inventory consists of 20 questions, divided into two equal subscales for positive and negative emotions, each with 10 items. The participants indicated the frequency they experience certain emotions, such as enthusiastic or ashamed, on a 5-point scale ranging from 1, “very slightly or not at all” to 5, “extremely”. The PANAS has been validated and demonstrates reliability, with an alpha coefficient range of .86 to .90 for positive affect and .84 to .87 for negative affect (Watson et al., 1988). The total scores are calculated by finding the sum of the 10 positive items and the sum of the 10 negative items. Scores for both positive and negative affect range from 10 to 50. A higher positive score (PANAS+) indicated a more positive affect. For the total negative score (PANAS-), a lower score indicates less negative affect. The measure takes approximately 2 minutes for participants to compete. (See 27.)

Qualitative data was collected through one open-ended question participants were invited to answer, “What makes you happy or proud about life on Prince Edward Island?” This gave participants the opportunity to write freely about specific aspects of life on PEI that contribute to well-being that may not have been captured in the quantitative data collection.

Demographic information was collected through a 17-question demographic survey, where participants identify community factors such as age, income, education, geography, gender, sexual orientation, immigration, and ethnicity. The demographic survey takes approximately 2 minutes for participants to complete. (See 28.)

Procedures

Striving for an equal probability of recruiting a representative sample of the population, efforts were made to maximize accessibility and recruit hard-to-reach participants from smaller communities. Participants were recruited through local newspapers and radio advertisements, community notice boards, and community social networks. Recruitment messaging focused on the aims of the research and driving traffic to the project central website, www.PEIwellbeingProject.ca. (See 29.) Total recruitment costs were $1200CAD. Once on the website, visitors can view the participation invitation letter (see 22), and consent letter (see 23), after which they can then choose to continue. Once consented, participants can access the online survey, administered using Qualtrics (www.quatrics.com). This design allowed for high accessibility and safety while producing robust data collection from across the province.

Data collection was open for 2 months, between October and November 2020. Participants began by answering the demographic survey, with the first two questions, “Do you live in PEI?” and “Are you 18 years old or older?” confirming their eligibility. Participants then completed the SWLS, PANAS, and WHO-QOL, followed by the open-ended qualitative question. Total participation time was approximately 10 to 15 minutes to complete, with participants having the choice to stop participation at any time. Upon completion, participants were directed to an online debrief letter (see 24).

Data Analysis began with transferring data from Qualtrics to SPSS software, where data was cleaned, and outliers removed. (See 30.) Appropriate assumptions such as normal distributions and common variance were checked prior to analysis. Using SPSS software, inferential statistics, using independent-sample T-tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA), compared mean scores of independent variables groups from demographic information with the dependent variables being well-being measures: SWLS, PANAS+, PANAS-, and WHO-QOL. Only results with statistical significance (p < .01) and a medium to large effect size (d > .4) were included when reporting results. In addition, multiple linear regression analysis was used to examine causal effects using the four WHO-QOL domain subscales as predictive variables of outcomes for SWLS and PANAS scores.

Qualitative data from the opened ended survey question was transferred from Qualtrics to NVivo™ software. Data was analyzed using a content analysis process (Elo & Kyngäs, 2008), which allowed for a quantitative treatment of the qualitative data. Frequency count identified words (including stemmed words) used in responses, with a 1% cut-off. The four quality of life subscale domains, psychical health, psychological, social relationships, and environment were used as grouping codes.

Although this is a mixed-method approach, focus and priority were given to the robust quantitative data. Data will be retained for five years after the research is completed.

Ethics and Risk Assessment

In designing this study, ethical considerations were assessed against the four principles of the British Psychological Society’s Code of Ethics (BPS, 2009), which include respect, competence, responsibility, and integrity. The BPS’s principle of respect provided the foundation for the design and reach of this research, as issues such as informed consent, confidentiality, comprehension, and inclusion were paramount. The nature of research this size involved collecting data from a large population and therefore had potential risks and ethical implications affecting a large group of participants. To increase safety and accessibility, and to adhere to public safety guidelines during the Covid-19 pandemic, all data was collected online. Although the online method allowed for greater reach and increase public safety measures, it raised considerations when obtaining informed consent. To address this, a detailed letter of invitation (22) and consent form (23) were created and clearly displayed on the research website. The letter of invitation includes the purpose of the research and all relevant information, such as assuring privacy and confidentiality, stating that participation is voluntary, anonymous, and with no identifiable data being collected. It also informs participants they have the right to stop their participation at any time throughout the survey. Obtaining anonymous signed consent forms online posed a challenge. To mitigate this, the consent form could be viewed online prior to participants choosing to click through to the survey link, with participants understanding that by continuing to the surveys they consent to the research.

The age of participants was limited to those 18 years or over for two reasons. First, to keep research focused on adults and secondly, to avoid any ethical issues pertaining to research involving youth. To maximize accessibility and increase participants’ full understanding and comprehension of research, the invitation letter, consent form, and debrief letters were written with a maximum grade 8 readability level. In the spirit of respect, additional considerations using an ethical framework of community-engaged research were used, which noted that when findings of the research are reported about a particular group, there are risks to the engaged groups (Ross et al., 2010). To mitigate this, all aggregated and generalized data was reported with no sense of judgement towards those groups, so to not present any group in a negative light. Potential risks or harm to participants have been acknowledged and although minimal risk, it is recognized that there is potential for emotional distress to participants from completing the online survey. To mitigate any psychological discomfort and demonstrate support and mutual respect, the debrief letter (24) includes contact information for the Canadian Mental Health Association as well as the PEI Help Line, if needed by participants. Furthermore, it has been acknowledged that there is a minor risk to the researcher. The researcher has access to support from research supervisors, peers, and local mental health services, if necessary. To ensure the research methods satisfy local ethics standards, approval was granted from PEI Research Ethics Board, in addition to the University of East London’s Ethics Board. (See 20 & 21.)

Results

With research taking place in the mists of the global COVID-19 pandemic, this study is reluctant to compare the total pollution means of well-being measures to data collected prior to the pandemic in 2020. Instead, this study will focus on statistically significant (p < .1) differences in well-being measures between groups, that show a medium or high effect sore (d > .4) and hopes to act as a new starting point for the continued measuring, tracking, and evaluating of happiness on Prince Edward Island.

Of the 1548 participants who took part in the online survey, after data cleaning, eligibility check, and removal of outliers, total participation was brought to n = 1381 for quantitative analysis and n = 1116 for those also answering the open-ended qualitative question.

Quantitative Results

When measuring the well-being of residents of PEI, results were evaluated using continuous scores of four dependent variables: satisfaction with life scale (SWLS), positive emotions sub-scale (PANAS+), negative emotions sub-scale (PANAS-), and the World Health Organization’s (brief) quality of life scale (WHO-QOL). Independent categorical variables included: age, immigration history, gender identity, sexual orientation, ethnicity (including Indigenous and Acadian), income, level of education, and region of PEI which participants lived in. These were assessed using means scores of the respective dependent variable scales.

Internal validity was satisfied for all scales and subscales with Cronbach’s alpha value between .70 to 1: SWLS (α = .99), PANAS+ (α = .90), PANAS- (α = .91), WHO-QOL total (α = .95), WHO-QOL Domain 1 (α = .89), Domain 2 (α = .88), Domain 3 (α = .73), Domain 4 (α = .86). Normal distributions of all dependent and independent variables are assumed as assessed by Q-Q plots. Homogeneity and equal sample sizes could not be assumed and Scheffé post-hoc tests were used to determine whether significant differences in means exist within each independent variable.

Descriptive findings of SWLS scores showed a total population mean of 22.5 (SD = 7.5) out of a potential 35, falling into a rage score of ‘slightly satisfied’. Findings from the PANAS+ scores showed total population means of 31.3 (SD = 7.5) out of a potential 50, with higher scores representing higher levels of positive affect. Findings from the PANAS- scores showed total population means of 21.0 (SD = 8.3) out of a potential 50, with lower scores representing lower levels of negative affect. Findings from the WHO-QOL scale showed total population means of 92.1 (SD = 18.5) out of a potential 130, with scores for separate domain subscales for, Physical health (M = 25.6 SD = 5.8) out of a maximum 35, Psychological (M = 19.7 SD = 4.9) out of a maximum 30, Social Relationships (M = 10.0 SD = 2.7) out of a maximum of 15 and Environment (M = 29.5 SD = 6.2) out of a maximum 40.

Further inferential results are reported below, following the order of the hypothesis listed earlier.

Age

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess differences in well-being scores according to participants age groups, 18–14 (n = 68), 25–34 (n = 208), 35–44 (n = 271), 45–54 (n = 277), 55–64 (n = 308), 65–74 (n = 209), 75–84 (n = 39) and above 85 years old (n = 2). SWLS, PANAS+, PANAS-, and WHO-QOL scores were all significantly different, p < .01, based on age, F(7,1384) = 11.43, F(7,1373) = 6.67, F(7,1373) = 32.78, F(7,1373) = 11.43. Post-Hoc tests revealed age brackets, that show statistically significant results from other age brackets are 75–84 and 64–74 years of age, found with large effect size.

Participants in age bracket 75–84 showed significantly higher effect scores of SWLS (M = 27.1, SD = 5.3) than all age groups 45–54 (M = 21.7, SD = 7.7, p = .01, 95% CI [.6, 10.2], d = 0.81) and below with effect and significant increasing as age groups decrees. Participants in age bracket 75–84 showed significantly higher effect scores of PANAS+ (M = 33.5, SD = 6.9) than all age groups 45–54 (M = 30.6, SD = 7.6, p = .04, 95% CI [.2, 9.8], d = 0.69) and below with effect and significance increasing as age groups decrees. Participants in age bracket 75–84 showed significantly lower effect scores of PANAS- (M = 13.8, SD = 4.1) than all age groups 55–64 (M = 19.0, SD = 7.3, p = .03, 95% CI [−10.2, −.3], d = 0.87) and below with effect and significance increasing as age groups decrees. Participants in age bracket 75–84 showed significantly higher effect scores of WHO-QOL (M = 105.8, SD = 12.8) than all age groups 55–64 (M = 92.2, SD = 20.2, p = .02, 95% CI [1.1, 26.0], d = 0.81) and below with effect and significance increasing as age groups decrees.

Participants in age bracket 65–74 showed significantly higher effect scores of SWLS (M = 25.5, SD = 6.4) than age all groups 45–54 (M = 21.7, SD = 7.7, p < .01, 95% CI [1.2, 6.4], d = 0.53) and below. Participants in age bracket 65–74 showed significantly lower effect scores of PANAS- (M = 16.7, SD = 6.8) than all age groups 45–54 (M = 21.7, SD = 8.2, p < .01, 95% CI [−7.6, −2.3], d = 0.66) and below. Participants in age bracket 65–74 also showed significantly higher effect scores of WHO-QOL (M = 99.1, SD = 16.1) than all age groups 45–54 (M = 88.3, SD = 20.5, p < .01, 95% CI [4.1, 17.5], d = 0.57) and below. No significant difference in the effect of PANAS+ scores was found between 65 and 74 and other age brackets.

Immigration

Two-tailed independent-sample t-tests were conducted to assess the difference in well-being scores between immigrants to Canada (n = 88) and those who were born in Canada (n = 1284). PANAS+ score was significantly higher [t(1370) = 3.72, p < .01, CI [1.45, 4.69], d = 0.4] for immigrant participants (M = 34.1, SD = 7.5) than participants born in Canada (M = 31.1, SD = 7.5). No significant difference in PANAS- scores was found between immigrants and participants born in Canada. WHO-QOL score was significantly higher [t(1370) = −2.05, p = .04, CI [0.17, 8.14], d = 0.23] for immigrant participants (M = 95.8, SD = 14.7) than those born in Canada (M = 1.7, SD = 18.5). No significant difference in SWLS scores was found between the two groups.

Disabilities

Two-tailed independent-sample t-tests were conducted to assess difference in well-being scores between disabled participants (n = 234) and able participants (n = 1146). SWLS score was significantly lower [t(1378) = −9.50, p = <.01, CI [−6.0, −4.0], d = 0.66] for disabled (M = 18.4, SD = 8.0) than able participants (M = 23.4, SD = 7.2). PANAS+ scores were significantly lower [t(1378) = −7.27, p = <.01, CI [−4.9, −2.8], d = 0.5] for disabled (M = 28.1, SD = 8.2) than able participants (M = 32.0, SD = 7.3). PANAS- scores were significantly higher [t(1378) = 7.00, p = <.01, CI [2.9, 5.2], d = 0.48] for disabled (M = 24.3, SD = 8.9) than able participants (M = 20.3, SD = 8.0). WHOQOL scores were significantly lower [t(1378) = −15.42, p = <.01, CI [−21.3, −16.5], d = 1.06] for disabled (M = 76.4, SD = 18.3) than able participants (M = 95.3, SD = 16.8).

LGBT

Two-tailed independent-sample t-tests were conducted to assess difference in well-being scores between LGBT participants (n = 149) and non-LGBT (n = 1216) participants. SWLS effect was significantly lower [t(1340) = −5.00, p = <.01, CI [−4.78, −2.12], d = 0.46] for LGBT participants (M = 19.4, SD = 7.9) than non-LGBT participants (M = 22.9, SD = 7.4). PANAS+ score was significantly lower [t(1340) = −2.48, p = <.01, CI [−3.12, −0.37], d = 0.23] for LGBT participants (M = 29.8, SD = 7.9) than non-LGBT participants (M = 31.5, SD = 7.4). Effect of PANAS- score was significantly higher [t(1340) = 5.81, p = <.01, CI [2.94, 5.93], d = 0.52] for LGBT participants (M = 24.9, SD = 8.9) than non-LGBT participants (M = 20.5, SD = 8.1). WHO-QOL effect was significantly lower [t(1340) = −6.94, p = <.01, CI [−14.07, −7.87], d = 0.59] for LGBT participants (M = 82.0, SD = 19.5) than non-LGBT participants (M = 93.2, SD = 18.1).

Gender Identity

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess difference in well-being scores according to participants gender identity, male (n = 219), female (n = 1138), or gender-diverse (n = 16). SWLS scores were significantly different based on gender identity F(2,1370) = 7.31, p < .01. Post-hoc tests found that effect was significantly lower for gender-diverse participants (M = 15.6, SD = 9.0) than both male (M = 22.2, SD = 8.0, p < .01, 95% CI [−11.4, −1.9], d = 0.7) and female participants (M = 22.7, SD = 7.4, p < .01, 95% CI [−11.7, −2.5], d = 0.86). No significant difference in PANAS+ scores were found between gender identities. PANAS- scores were significantly different based on gender identity F(2,1370) = 4.34, p = .01. Post-hoc tests found that effect was significantly higher for gender diverse participants (M = 26.4, SD = 9.4) than both male (M = 20.3, SD = 8.0, p = .02, 95% CI [0.9, 11.4], d = 0.71) and female participants (M = 21.0, SD = 8.3, p < .01, 95% CI [0.3, 10.5], d = 0.61). WHO-QOL scores were also significantly different based on gender identity F(2,1370) = 7.48, p = <.01. Post-hoc tests found that effect was significantly lower for gender diverse participants (M = 74.4 SD = 22.6) than both male (M = 92.6, SD = 20.0, p < .01, 95% CI [−29.9, −6.53], d = 0.85) and female participants (M = 92.2, SD = 18.1, p < .01, 95% CI [−29.16, −6.42], d = 0.87.

Indigenous

Two-tailed independent-sample t-tests were conducted to assess difference in well-being scores between indigenous participants (n = 40) and those non-indigenous (n = 1221). SWLS scores were significantly lower [t(1259) = 4.37, p = .01, CI [−7.64, −2.9], d = 0.66] for indigenous participants (M = 17.4, SD = 8.6) than non-indigenous participants (M = 22.7, SD = 7.5). PANAS+ scores were significantly lower [t(1259) = −3.34, p = <.01, CI [−6.4, 1.7], d = 0.5] for indigenous (M = 27.4, SD = 8.3) than non-indigenous participants (M = 31.5, SD = 7.4). PANAS- scores were significantly higher [t(1259) = 4.50, p = <.01, CI [3.3, 8.5], d = 0.70] for indigenous (M = 26.8, SD = 8.8) than non-indigenous participants (M = 20.8, SD = 8.2). WHO-QOL score were significantly lower [t(1259) = −4.80, p = <.01, CI [−19.8, −8.3], d = 0.76] for indigenous (M = 78.3, SD = 18.42) than non-indigenous participants (M = 92.4, SD = 18.2).

Acadian

No significant difference in SWLS, PANAS or WHO-QOL scores were found between the Acadian participants (n = 143) and the rest of the sample population (n = 1164).

Other Ethnicities

No statistically significant results were found among other ethnicities included in this study: Middles Eastern (n = 4), Black (n = 7), East Asian (n = 6), Hispanic (n = 8), Pacific Islanders (n = 4), South Asian (n = 6), Southeast Asian (n = 3).

Education Level

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess difference in well-being scores according to education levels: some high school (n = 39), high school graduate (n = 242), vocational certificate (n = 198), university degree (n = 696), master’s degree (n = 163), doctorate degree (n = 39). SWLS, PANAS+, PANAS-, and WHO-QOL scores were all significantly different, p < .01, based on education level, F(5,1372) = 11.72, F(5,1372) = 13.28, F(5,1372) = 7.25, F(5,1372) = 16.91. Post-Hoc tests revealed participants with master’s levels education reporting higher well-being than participants with university, trade, and lower levels of education. Master’s educated participants showed significantly higher effect scores of SWLS (M = 26.1, SD = 6.2) than those with university degrees (M = 22.2, SD = 7.5, p < .01, 95% CI [1.8, 6.0], d = 0.56), vocational certificates (M = 22.3, SD = 7.0, p < .01, 95% CI [1.1, 6.3], d = 0.56) and high school diploma (M = 21.12, SD = 8.0, p < .01, 95% CI [.82, 9.3], d = 0.69. Master’s educated participants showed significantly higher effect scores of PANAS+ (M = 34.7, SD = 5.7) than those with university degrees (M = 31.3, SD = 7.3, p < .01, 95% CI [1.3, 5.6], d = .51), vocational certificates (M = 30.5, SD = 7.7, p < .01, 95% CI [1.6, 6.8], d = .61) and high school diploma (M = 29.9, SD = 7.8, p < .01, 95% CI [2.4, 7.3], d = .70. Master’s educated participants showed significantly lower effect scores of PANAS- (M = 17.7, SD = 5.9) than those with university degrees (M = 21.3, SD = 8.1, p < .01, 95% CI [−6.0, −1.2], d = .51), vocational certificates (M = 21.0, SD = 8.5, p = .01, 95% CI [−6.2, −.5], d = .45) and high school diploma (M = 22.2, SD = 8.8, p < .01, 95% CI [−7.2, −1.8], d = .60. Master’s educated participants showed significantly higher effect scores of WHO-QOL (M = 102.3, SD = 13.0) than those with university degrees (M = 91.5, SD = 18.5, p < .01, 95% CI [5.6, 16.0], d = 68), vocational certificates (M = 91.6, SD = 17.8, p < .01, 95% CI [4.3, 17.0], d = 68) and high school diploma (M = 87.2, SD = 19.7, p < .01, 95% CI [9.0, 21.12], d = 90.

Income

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess differences in well-being scores according to participants annual household income: less than $15,000 (n = 90), $15,000–$30,000 (n = 210), $30,000–$45,000 (n = 183), $45,000–$60,000 (n = 154), $60,000–$75,000 (n = 160), $75,000–$100,000 (n = 190), $100,000–$150,000 (n = 169), and $150,000 or above (n = 91). SWLS, PANAS+, PANAS-, and WHO-QOL scores were all significantly different, p < .01, based on income, F(8,1371) = 34.11, F(8,1371) = 11.29, F(8,1371) = 10.97, F(8,1371) = 32.42.

Post-Hoc tests revealed participants who earn less than $15,000 a year have significantly lower SWLS scores (M = 14.5, SD = 7.0) than those who earn $15,000–$30,000 (M = 19.5, SD = 7.6, p < .01, 95% CI [−8.5, −1.6], d = 0.68) or above, with effect and significance increasing when compared with higher incomes brackets. Those who earn less than $15,000 showed to have significantly lower PANAS+ scores (M = 27.3, SD = 7.5) than those who earn $60,000–$75,000 (M = 31.9, SD = 6.6, p < .01, 95% CI [−8.3, −.7], d = .65). Those who earn less than $15,000 showed to have significantly higher PANAS- scores (M = 27.1, SD = 9.3) compared to those who earn $15,000–$30,000 (M = 22.5, SD = 9.2, p < .01, 95% CI [.6, 8.6], d = .60), or above, with effect and significance increasing when compared to higher income brackets. Additionally, those who earn less than $15,000 showed to have significantly lower WHO-QOL scores (M = 73.2, SD = 19.0) compared to those who earn $30,000–45,000 (M = 88.3, SD = 20.7, p < .01, 95% CI [−15.6, −1.6], d = .76), or above, with effect and significance increasing when compared to higher income brackets.

Post-Hoc tests revealed participants who earn $15,000–$30,000 annual have significantly lower SWLS (M = 19.5, SD = 7.7) and WHO-QOL (M = 82.0, SD = 20.9) scores compared to those who earn $60,000–$75,000 a year [(M = 23.1, SD = 7.2, p < .01, 95% CI [−6.5, −.7], d = .48), (M = 92.8, SD = 20.0, p < .01, 95% CI [−18.3, −3.2], d = .53)]. Those who earn $15,000–$30,000 a year reported, significantly lower PANAS+ scores (M = 29.1, SD = 8.1) than $75,000–$100,00 earners (M = 32.7, SD = 6.4, p < .01, 95% CI [−6.5, −.71], d = .49) and higher PANAS- scores (M = 22.5, SD = 9.1) than those who earn $150,000 or more (M = 18.1, SD = 7.2, p = .02, 95% CI [.4, 8.4], d = .53).

Post-Hoc tests revealed participants who earn $30,000–$45,000 a year have significantly lower SWLS (M = 21.0, SD = 7.8) and WHO-QOL (M = 89.6, SD = 17.5) scores compared to those who earn $75,000–$100,000 a year [(M = 25.2, SD = 5.7, p < .01, 95% CI [−7.1, −1.4], d = .66), (M = 98.5, SD = 14.5, p < .01, 95% CI [−17.7, −2.7], d = .75)] or above, with effect and significance increasing when compared to higher income brackets. No significant effect in PANAS+ or PANAS- was found between higher income brackets.

Post-Hoc tests revealed participants who earn $45,000–$60,000 a year have significantly lower SWLS (M = 21.7, SD = 7.5) and WHO-QOL (M = 89.6, SD = 17.5) scores when compared to those who earn $75,000–$100,000 a year [(M = 25.2, SD = 5.7, p < .01, 95% CI [−6.5, −.6], d = .62), (98.5, SD = 14.5, p < .01, 95% CI [−16,7, −1.1], d = .56)] or above, with effect and significance increasing when compared to higher income brackets. No significant effect in PANAS+ or PANAS- was found between higher income brackets.

No significant effect in SWLS, PANAS+, PANAS-, or WHO-QOL scores was found between participants who earn $60,000–$75,000 a year, $75,000–$100,000 and above.

Regional PEI

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess differences in well-being scores between the three regions in the province, Prince County (n = 328), Queens County (n = 898), and Kings County (n = 165). Please note the regional findings, though showing statistically significant differences (p < .1) in well-being measures, have an effect size below the sufficiency cut of d > .4, though as they approach the edge of significance, it seemed appropriate to mention them in this report.

PANAS positive (PANAS+) scores were significantly different based on region F(2,1379) = 6.23, p < .01. Post-hoc tests found that effect was significantly higher for Queens County (M = 31.6, SD = 7.3) than Prince County (M = 30.3, SD = 8.2, p = .02, 95% CI [0.14, 2.52]), found with low effect size (d = 0.16). PANAS negative (PANAS-) scores were significantly different based on region F(2,1379) = 5.30, p < .01. Post-hoc tests showed that effect was significantly lower for Kings County (M = 19.1, SD = 7.4) than Queens County (M = 21.0, SD = 8.2, p = .03, 95% CI [−3.69, −0.18]), found with low effect size (d = 0.24). PANAS- effect was also significantly lower for Kings County than Prince County (M = 21.7, SD = 8.8, p < .01, 95% CI [−4.56, −0.63]), found with a low effect size (d = 0.33). WHO-QOL scores were significantly different based on region F(2,1379) = 3.22, p = .04. Post-hoc tests found that effect was significantly higher for Queens (M = 92.8, SD = 18.1) than Prince County (M = 89.8, SD = 19.6, 95% CI [.07,5.91]), found with low effect size (d = 0.16). There was no significant effect between SWLS and regions participants lived in.

Two multiple regressions were performed to estimate the relationship between both the SWLS and PANAS scores as the outcome variables and the four WHO-QOL domains (physical health (D1), psychological health (D2), social relationships (D3), and environment (D4)) as independent variables; each of which did not violate normality assumptions, as assessed by Q-Q Plots. PANAS scores were calculated using the combined subscale scores of PANAS+ and inverted PANAS- scores. The assumption of collinearity was satisfied for both SWLS and PANAS, with values in the ranges .45–.68 and .46–.69, respectively. None of the predictors is colinear. There were no outliers among the residuals ± 3 standard deviations from the means and no Cook’s distance above 1.

Results of the first multiple linear regression, using SWLS as the outcome, indicated there was a collective significant effect between WHO-QOL domains and SWLS (F(4, 1376) = 684.5, p < .001, R2 = .66). The individual predictors, D1, D2, D3, D4 were examined further and indicated that domain 2, psychological health (t(4, 1376) = 14.45, β = .37, p < .001) and domain 4, environment (t(4, 1376) = 15.19, β = .37, p < .001) were significant predictors in the SWLS model, F2 = 1.99.

Results of the second multiple linear regression, using the PANAS scale as the outcome, indicated that there was a collective significant effect between WHO-QOL domains and PANAS (F(4, 1376)=, p < .001, R2 = .74). The individual predictors, D1, D2, D3, D4 were examined further and indicated that domain 2, psychological health (t(4, 1376) = 33.91, β = .76, p < .001) was a significant predictor in the PANAS model, F2 = 2.86.

Qualitative Results

A content analysis was conducted on the qualitative data collected from the open-ended question, ‘What makes you happy or proud about your life in PEI?’ A word frequency count identified words, including stemmed words, most used throughout the participant’s responses (n = 1116), using a cut-off of weighted word percentage of >1.0%. Results indicated the word ‘people’ was used most frequently, with a weighted percentage of 2.28%, followed by; ‘beauty’ (1.87%), ‘safe’ (1.46%), ‘love‘ (1.34%), ‘community’ (1.28%), ‘family’ (1.15%), and ‘friends’ (1.12%). Below are some examples, selected manually, of participant responses:

“Beautiful landscape and beaches, kind and generous people who look out for each other. Strong sense of community.”

“It feels like a reasonably safe place to be, but l would rather be in Charlottetown [Queens County] area as opposed to a more rural area.”

“Safe beautiful environment, people are friendly and helpful. We have a comfortable lifestyle.”

“It is beautiful with friendly and community-minded people.”

“How safe it is, how beautiful it is, my child has an excellent quality of life, calm pace, not violent.”

“Natural beauty all around, trees, beaches, water views. Great food! Family and community”

Coding units were assigned to words according to the (WHO-QOL’s) four life domains, physical health (D1), psychological health (D2), social relationships (D3) and environment (D4). Analysis revealed words coded as social relationships (D3) and environment (D4) appeared most frequently in participants’ responses to, what makes them happy or proud about life in PEI. Although this analysis was able to quantify substantial amounts of qualitative data collected by providing descriptive word frequencies of responses, it is limited to no further extraction of any deeper meaning or explanation. It was included to complement the quantitative data.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to gain a better understanding of the subjective well-being of residents of Prince Edward Island, Canada, through a scientific exploration of happiness. There are six key findings of the present research:

-

Finding 1: Psychological health and a healthy environment were demonstrated as important contributors to the well-being of residents of PEI.

-

Finding 2: This study showed lower levels of cognitive and affective well-being among diverse populations including, LGBT, gender diverse, Indigenous, disabled, and those living under the poverty line.

-

Finding 3: The elderly populations in PEI experience higher levels of both cognitive and affective well-being than the rest of the younger population.

-

Finding 4: Findings indicate immigrants to Canada, living in PEI, tend to experience higher positive emotions than Canadian-born.

-

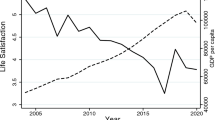

Finding 5: The research supports current theories that a) income contributes to limited cognitive well-being, and b) income has an insignificant effect on affective well-being.

-

Finding 6: This study showed that a master’s level of education had a positive effect on both cognitive and affective well-being.

The present study lends insight to the following hypotheses, discussed earlier, of subjective well-being:

-

Age: Results showed no meaningful change in well-being scores as age increased until participants reached age 45–55, at which point well-being increased as age went up. These findings support the latter half of Graham and Pozuelo’s (2017) U-shaped findings, that people in their 60’s and 70’s have higher well-being than those in their 40’s & 50’s, but did not support their findings of people in their 20’s being happier than those in their 40’s or 50’s.

-

Immigration: Although these results are consistent with suggestions that only subtle differences exist in perceived quality of life between immigrants and Canadian-born (Randall et al., 2014; Frank et al., 2016) this study found that immigrants to Canada experience a higher measurable level of positive emotions than those born in Canada, shown with a medium effect size.

-

Life Circumstances: Findings are consistent with the literature (Lucas, 2007), showing that disabled participants experience lower well-being than able participants, with lower measurable levels of life satisfaction and quality of life, shown through large effect size, and experience lower levels of positive emotions and higher levels of negative emotions, shown through medium effect size. Higher negative emotions could be contributed by feelings of isolation from communities (Hedberg & Skärsäter, 2009).

-

Income: Findings indicate a distinct income threshold with those who make less than $15,000 annually, reporting significantly lower satisfaction with life and higher negative emotions than those who earn $15,000 or above, and report lower quality of life than those who earn less than $30,000 and above, shown with large effect size. Notable changes in positive emotions were reported once income exceeded $60,000, also shown with a large effect size. These results lend support to Kahneman and Deaton’s (2010) findings that income has a greater effect on how individuals evaluate their lives and a lesser effect on the positive or negative emotions they feel. Supported further by no significant difference found in positive or negative emotions after income had reached $30,000. Results also found those who make between $15,000–$30,000 did not see a significant difference in reported satisfaction with life or quality of life until income reached $60,000, with no significant differences found between incomes above $60,000. This threshold supports research, revealing that income serves to fulfil well-being needs to a point but has a ceiling (Jebb et al., 2018). These findings suggest a minimum income threshold exists that has a significant effect on both cognitive and affective well-being.

-

Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity: Consistent with reports by de Vries et al. (2020), this research found that LGBT participants experience a lower level of reported well-being than non-LGBT participants, with lower satisfaction with life, higher negative emotions, and a lower quality of life, shown through medium effect size. Findings also support Davey et al.’s (2014) research with gender diverse participants reporting lower levels of satisfaction with life, higher negative emotions, and lower quality of life, shown through large effect size.

-

Indigenous Communities: Results found, according to the western measurement of well-being being used in the research, that Indigenous participants on PEI have lower self-reported well-being than non-indigenous, with lower satisfaction with, lower positive emotions, higher negative emotions, and lower quality of life, shown through large effect size. The results lend support to work by Schill et al. (2019), stating that Indigenous people experience a greater burden of poor health and wellness relative to non-Indigenous Canadians.

-

Levels of Education: Exploratory analysis found levels of education effects well-being. For instance, the masters-educated participant reported higher levels of well-being than those with university or lower levels of education, with higher satisfaction with life, higher positive emotions, lower negative emotions, and a higher quality of life, shown through medium effect size. These results support claims by Nikolaev (2018) that levels of education effects both perceived quality of life and emotions. In this study, the differences are only seen once a master’s level is reached.

-

Regional: Exploring results from the multiple linear regression found two strong quality of life predictors influencing satisfaction with life in PEI. The first predictor is a healthy environment, such as a sense of safety, accessibility, and natural environment, which lends support to Novaczek et al.’s (2011) research, suggesting residents have an acute sense of place, that highly value beaches, rivers, and coastal properties. Secondly, psychological health, such as enjoyment of life, sense of meaning and self-acceptance is a strong predictor of satisfaction with life on the Island. Results from the second regression analysis found psychological health to also be a strong predictor of the positive and negative emotions people in the province feel. These findings can contribute to PEI’s community accounts, as suggested by LeVangie et al. (2011).

Qualitative findings revealed aspects of social relationships and a healthy environment were frequently used when Islanders reflected on what makes them happy about life in PEI. Comments such as “Beautiful landscape and beaches, kind and generous people who look out for each other. Strong sense of community,” and “It is beautiful with friendly and community-minded people.” These comments reflect aspects of ‘islandness,’ where islands create a sense of place close to nature, where neighbours are embraced (Conkling, 2007).

Exploratory quantitative analysis revealed subtle differences, with low effect size, in well-being amongst different regions of PEI in which participants lived in. Findings suggest that those living in Kings County experience fewer negative emotions than those in both Queens and Prince County. Although the effect size is too small to report with confidence, it is worth mentioning as further research could explore, with larger effect size, if the lower level of a particular negative emotion is a unique characteristic of the region, which positively impacts the well-being of those who live there.

Limitations

Although the present study clearly identifies differences in well-being within the province, it is appropriate to recognize several limitations. First, due to the public safety measures of Covid-19, the methodology choice was limited to online. Despite efforts to have participation from a full representative of the population, this study fell slightly short. For instance, there was an under-representation of male participants in the study, which could introduce a gender bias into the results. Future research needs to put focus on recruiting male participants, in addition to the Asian population and people of colour, whose participation in this study seemed proportionately low. This would include more identifiable groups who may be underrepresented in this research. Secondly, though this study was limited to English participation, all three self-ported surveys used are translated and validated in multiple languages. To honour Canada’s second official language and to increase participation of both Francophone and Asian residents, further research could include surveys translated into French and Mandarin. Thirdly, this research on well-being recognizes that Indigenous communities in Canada and in PEI, have different holistic views of happiness than the western tools being used in this study. The researcher acknowledges these differences and assures that despite their limited knowledge of the indigenous culture, the spirit of this research is to bring greater well-being to all and gives thanks for their participation. Finally, with research showing that religion influences subjective well-being (Hackney & Sanders, 2003), this study is limited as the tools selected do not include spirituality in their measures. Lastly, an error in the demographic survey design (of option to ‘select all that apply’) forced the exclusion of two independent variables, occupation, and relationship status, from being analyzed, limiting the scope of the investigation.

Implications

Despite these limitations, this study has contributed to the knowledge of community well-being research in the following ways. Firstly, by shining a light on the need to address the inequity in well-being among minority populations including, LGBT, gender diverse, Indigenous, disabled, and those living under the poverty line. Secondly, the study provided a deeper understanding of what Islanders view as important aspects of their well-being. Thirdly, these results build on the existing theories of the relationships between well-being and income, age, and education. Finally, this research provides an outset and methodology for the continuous measurement and tracking of both the affective and cognitive accounts of well-being on Prince Edward Island and can be replicated in other populations or in island studies around the world.

Recommendations

Based on the discussion of these results practical implementation has been acknowledged. In terms of further research, it would be useful to add an additional level of analysis, whereby using each of the four WHO-QOL subscales as unique dependent variables. This deeper level of analysis was beyond the scope of this study but could give deeper insight into individuals’ perception of each quality-of-life domain separately, allowing for a richer investigation. Further research into the inequities of well-being in identified groups could include another layer of analysis using PANAS scores to investigate emotions on a more granular level. Identifying any significant difference in an isolated emotion could give insight into possible community-based interventions. This type of granular investigation could also give more insight into the specific positive emotions identified to be felt more frequently by immigrants to Canada. In addition, future research could explore the question of an inter-sectional and possible causal relationship between the different variables. Moreover, when considering environmental factors that influence SWB, there is the possibility of confirmation bias. That it, those people who value certain environmental factors are more likely to have remained in the community, while those who do not value them may have migrated out of the community. Future research with different populations would be required to understand the contribution of such factors to populations overall, as the results of this study are unique to Prince Edward Island.

This report highlights that Islanders consider psychological well-being, such as enjoyment of life, self-acceptance, positive emotions, and a healthy environment in which they live, as important influencers towards their subjective well-being. Policymakers should prioritize appropriately when taking actions toward enhancing well-being across the province.

This research intends to act as encouragement and momentum for research bodies and policymakers to support the continued measurement and tracking of subjective well-being over time. Demonstrated from this report, it allows us to identify those groups who are falling behind and those progressing towards their pursuit of a good life.

Conclusion

This research answers the call of the World Happiness Report (Sachs et al., 2018) to begin the systematic measurements of happiness, in both affective and evaluative dimensions and applied it at a local and provincial level through an account of well-being in Prince Edward Island, Canada. These findings are relevant because they allow for a scientific evaluation of happiness to expose the inequities of well-being among marginalized groups, such as Indigenous, those who identify as LGBT or gender diverse, those with disabilities, or those who earn under the poverty line. Attention should be given to community-based well-being interventions targeting these groups. A potential way of increasing the well-being of all PEI residents would be through prioritizing the psychological needs of citizens in addition to strengthening the health of the environment in which they live. Furthermore, this report offers insight and tools that allow for replicated studies to take place, allowing policymakers to prioritize and track the effectiveness of initiatives regarding the happiness of their citizens. This research provides insight into happiness as an indicator of how society is performing and was intended to give momentum towards the adoption of sustainable development goals, such as national happiness (Helliwell et al., 2019). It is the hope of the author that research into happiness, such as this, can be encouraged and replicated in more communities and provinces across Canada or in island studies around the world.

Data Availability

The author is prepared to send relevant data in order to verify the validity of the results presented. This would be in the form of raw anonymous data in SPSS format. All software’s used (Qualtrics, SPSS, and Nvivo) comply with field standards.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Armenta, C. N., Ruberton, P. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2015). Psychology of subjective well-being. International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, 2(23), 648–653.

Bartels, M. (2015). Genetics of well-being and its components satisfaction with life, happiness, and quality of life: A review and meta-analysis of heritability studies. Behavior Genetics, 45(2), 137–156.

BPS. (2009). Code of ethics and conduct. The British Psychological Society.

Conkling, P. (2007). On islanders and islandness. Geographical Review, 97(2), 191–201.

Davey, A., Bouman, W. P., Arcelus, J., & Meyer, C. (2014). Social support and psychological well-being in gender dysphoria: A comparison of patients with matched controls. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11(12), 2976–2985.

Deaton, A., & Stone, A. A. (2016). Understanding context effects for a measure of life evaluation: How responses matter. Oxford Economic Papers, 68(4), 861–870.

Diener, E. (2009). Subjective well-being. In: E. Diener (Eds.), The science of well-being. Social Indicators Research Series (Vol. 37, pp. 11–58). Springer, Dordrecht.

Diener, E., & Chan, M. Y. (2011). Happy people live longer: Subjective well-being contributes to health and longevity. Applied Psychology. Health and Well-Being, 3(1), 1–43.

Diener, E., & Diener, M. (2009). Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. In Culture and Well-being (pp. 71–91). Springer.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. (2004). Beyond money: Toward an economy of well-being. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 5(1), 1–31.

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Diener, E., Sapyta, J. J., & Suh, E. (1998). Subjective well-being is essential to well-being. Psychological Inquiry, 9(1), 33–37.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302.

Diener, E., Ng, W., Harter, J., & Arora, R. (2010). Wealth and happiness across the world: Material prosperity predicts life evaluation, whereas psychosocial prosperity predicts positive feeling. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(1), 52.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2015). National accounts of subjective well-being. American Psychologist, 70(3), 234–242.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Tay, L. (2018). Advances in subjective well-being research. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(4), 253–260.

Dolan, P., & Metcalfe, R. (2012). Measuring subjective well-being: Recommendations on measures for use by national governments. Journal of Social Policy, 41(2), 409–427.

Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115.

Frank, K., Hou, F., & Schellenberg, G. (2016). Life satisfaction among recent immigrants in Canada: Comparisons to source-country and host-country populations. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(4), 1659–1680.

Fredrickson, B. L., Tugade, M. M., Waugh, C. E., & Larkin, G. R. (2003). What good are positive emotions in crisis? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 365–376.

Graham, C., & Pozuelo, J. R. (2017). Happiness, stress, and age: How the U curve varies across people and places. Journal of Population Economics, 30(1), 225–264.

Hackney, C. H., & Sanders, G. S. (2003). Religiosity and mental health: A meta–analysis of recent studies. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42(1), 43–55.

Headey, B., & Wearing, A. J. (1992). Understanding happiness: A theory of subjective well-being. Longman Cheshire.

Hedberg, L., & Skärsäter, I. (2009). The importance of health for persons with psychiatric disabilities. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 16(5), 455–461.

Heffetz, O., & Rabin, M. (2013). Conclusions regarding cross-group differences in happiness depend on the difficulty of reaching respondents. American Economic Review, 103(7), 3001–3021.

Helliwell, J. F., Bonikowska, A., & Shiplett, H. (2016). Migration as a test of the happiness set point hypothesis: Evidence from immigration to Canada (Vol. No. w22601). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Helliwell, J., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (2019). World happiness report 2019. Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Jebb, A. T., Tay, L., Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2018). Happiness, income satiation and turning points around the world. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(1), 33–38.

Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(38), 16489–16493.

Larsen, R. J., Diener, E. D., & Emmons, R. A. (1985). An evaluation of subjective well-being measures. Social Indicators Research, 17(1), 1–17.

LeVangie, D., Enman, S., Novaczek, I., MacKay, R., & Clough, K. (2011). Quality of Island Life Survey: Tyne Valley & Surrounding Areas (p. 2006).

Lucas, R. E. (2007). Long-term disability is associated with lasting changes in subjective well-being: Evidence from two nationally representative longitudinal studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 717–730.

Lucas, R. E., Diener, E., & Suh, E. (1996). Discriminant validity of well-being measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(3), 616–628.

Lykken, D. (1999). Happiness: What studies on twins show us about nature, nurture, and the happiness set-point. Golden Books.

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131(6), 803–855.

Moore, S., Diener, E., & Tan, K. (2018). Using multiple methods to more fully understand causal relations: Positive affect enhances social relationships. In Handbook of Well-Being. DEF Publishers.

Nikolaev, B. (2018). Does higher education increase hedonic and eudaimonic happiness? Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(2), 483–504.

Novaczek, I., MacFadyen, J., Bardati, D., & MacEachern, K. (2011). Social and cultural values mapping as a decision-support tool for climate change adaptation. The Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island.

Oishi, S., Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Suh, E. M. (2009). Cross-cultural variations in predictors of life satisfaction: Perspectives from needs and values. In Culture and well-being (pp. 109–127). Springer.

Prince Edward Island Statistics Bureau. (2021). PEI Populations Report 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2021 from https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/sites/default/files/publications/pt_pop_rep_0.pdf

Randall, J. E., Kitchen, P., Muhajarine, N., Newbold, B., Williams, A., & Wilson, K. (2014). Immigrants, islandness and perceptions of quality-of-life on Prince Edward Island, Canada. Island Studies Journal, 9(2), 343–362.

Ross, L. F., Loup, A., Nelson, R. M., Botkin, J. R., Kost, R., Smith Jr., G. R., & Gehlert, S. (2010). Human subjects protections in community-engaged research: A research ethics framework. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 5(1), 5–17.

Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(4), 719–727.

Sachs, J. D., Layard, R., & Helliwell, J. F. (2018). World happiness report 2018 (No. id: 12761) https://worldhappiness.report/ed/2018/

Schill, K., Terbasket, E., Thurston, W. E., Kurtz, D., Page, S., McLean, F., et al. (2019). Everything is related and it all leads up to my mental well-being: A qualitative study of the determinants of mental wellness amongst urban indigenous elders. The British Journal of Social Work, 49(4), 860–879.

Schneider, L., & Schimmack, U. (2009). Self-informant agreement in well-being ratings: A meta-analysis. Social Indicators Research, 94(3), 363–376.

Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2011). Needs and subjective well-being around the world. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 354.