Abstract

Gallbladder papillary carcinoma is a less common form of gallbladder carcinoma that accounts for around 5% of all gallbladder malignancies. Because of its early manifestation and delayed invasion in the gallbladder wall, it has a better prognosis than adenocarcinoma. It is quite rare for it to manifest as cholecystocolic fistula. Imaging aids in the diagnosis of the lesion and associated fistula, as well as in determining the surgical extent of excision. Histology further aids in accurate diagnosis by recognizing the papillary architecture of the tumor as well as the extent of invasion. We herein present a case of a 51-year-old female who presented with symptoms of abdominal pain and vomiting for a month. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed thickened gallbladder wall with the presence of cholecystocolic fistula and enlarged pericholecystic lymph node. Cholecystectomy with excision of fistulous tract and lymph node was done, which showed gallbladder papillary carcinoma with metastasis to lymph node. After surgery, the patient received chemotherapy and was followed for 2 years with no symptoms of recurrence. To summarize, papillary gallbladder cancer is less prevalent and has a better prognosis than adenocarcinoma. Imaging and histology are critical in identifying the lesion and determining the best treatment option.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) is the most common biliary tract malignancy. GBC has various subtypes, with adenocarcinoma being the most frequent, accounting for 80–97% of cases [1]. Papillary, mucinous, squamous, and adenosquamous are the other less common subtypes of GBC [1]. Among these subtypes, gallbladder papillary adenocarcinoma (GBPA) accounts for 5% of all gallbladder (GB) malignancies [2]. It is crucial to distinguish these subtypes on histology since they have varied prognoses. In contrast to the poor prognosis of adenocarcinoma, the papillary subtype has a better prognosis, which is attributed to the patient’s early clinical presentation due to obstruction, exophytic growth, and delayed GB wall invasion [2,3,4,5].

Case Report

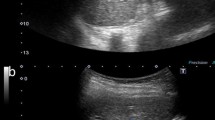

A 51-year-old female patient presented to the outpatient department with complaints of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting for 1 month. The vitals of the patient including blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate were stable. Laboratory investigations were within normal limits and are as follows: hemoglobin, 11.4 g/dl; white cell count, 8.7 × 109/L; and platelet count, 350 [10^3/ul]. Other tests like renal and liver function tests were also within normal limits. In view of the above symptoms, contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) abdomen was done, which revealed thickening of the GB wall with the presence of focal T2 hyperintense rent of size ~ 3.8 mm in medial wall of GB communicating with adjacent hepatic flexure of colon suggestive of cholecystocolic fistula. A small lymph node was seen adjacent to the GB neck, measuring 12 × 8 mm. Based on imaging findings, cholecystectomy and excision of pericholecystic lymph node were performed. The GB measured 4.7 × 2 × 1.7 cm in size, with a wall thickness ranging from 0.2 to 0.6 cm. A tiny suture-marked fistula measuring 1.2 cm was noted. The mucosa was ulcerated, and the fundus revealed papillary growth. However, there were no stones. The GB revealed hyperplastic columnar lining on microscopic examination. The lamina propria and muscularis propria revealed an invasive tumor with a papillary pattern consisting of various sized papillae, including small villiform or broad papillae, many of which showed branching, and a fibrovascular core. The tumor cells were columnar, with vesicular nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and moderate cytoplasm (Fig. 1). Tumor cells were noted infiltrating the subserosal tissue (Fig. 2). A pericholecystic lymph node measured 1 × 0.7 cm and revealed tumor metastases with similar morphology on microscopy (Fig. 3). The final diagnosis was GBPA with metastases to the pericholecystic lymph node. Following that, the patient received chemotherapy and was followed for 2 years with no evidence of tumor recurrence. No family history of GB disease has been found.

Discussion

GBC is the most common biliary tract malignancy with poor prognosis. Gallbladder adenocarcinoma (GBA) is the most common type of GBC with poor prognosis [1, 2]. GBPA is a subtype of GBC with better prognosis than adenocarcinoma [1, 2].

GBPA is more common among women in their 70 s. The etiology of GB stones is similar to that of adenocarcinoma [4, 6]. Both, however, have diverse clinical presentation. Patients with GBPA have fever in half of the cases, which could be explained by its exophytic nature, which leads to detachment of some friable tumor tissue, formation of emboli, and eventually clogging the lumen of the cystic duct and producing fever [4, 6]. According to a few cases, preoperative jaundice is a poor prognostic factor and is thought to indicate tumor involvement in the extrahepatic biliary network [7]. The imaging findings of GBA and GBPA are presence of intraluminal mass. There may be focal or widespread GB wall thickening. However, this feature is more common in GBA, indicating its aggressive and invasive nature [8]. GBPA, on the other hand, typically exhibits exophytic growth in the lumen and is therefore less invasive. The pathophysiology of papillary lesions of GB is unknown, but it is thought to be related to other pancreaticobiliary papillary lesions. These are often indolent in nature and exhibit comparable biological behavior to intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas and intraductal bile duct neoplasms [7].

The vast majority of GBPA cases present early and are carcinoma in situ. GBA, on the other hand, frequently manifests at a later stage, such as T3 or T4, and has a poor prognosis. According to one study by Wan X et al., just one out of 98 GBA instances had in situ lesions, with the rest having invasive lesions. Four of the sixteen GBPA patients, however, had cancer in situ with no signs of invasion [7].

Based on morphological characteristics, GBPA is further classified as invasive and non-invasive. Both of these subgroups are characterized by a biliary phenotype [9]. In most cases, the invasive component is a tubular component, but it can also have undifferentiated or mucinous components [10, 11]. Most of the non-invasive papillary carcinoma presents as carcinoma in situ lesions, suggesting its indolent behavior. Invasive papillary carcinomas have different prognosis than invasive nonpapillary carcinomas of the GB, which include adenocarcinomas NOS, mucinous carcinomas, and adenosquamous carcinomas. According to a study conducted by Saavedra et al., invasive papillary carcinomas have a 52% 10-year survival rate, while other nonpapillary invasive carcinomas have a 30% survival rate, suggesting that invasive papillary carcinoma has a better prognosis than invasive nonpapillary carcinoma [4].

Following a review of the literature, we discovered a case report by Gi Won Ha et al. of cholecystocolic fistula caused by GBC [12]. In addition, Jenn-Yuan Kuo et al. published a case report of biliary papillomatosis with cholecystocolonic fistula in a single patient [13]. However, no case report of GBPA presenting as cholecystocolic fistula has been found, and we believe that our case report is the first case of cholecystocolic fistula caused by GBPA.

A few recent research on the clinicopathological aspects of GBPA have also been published. Kang JS did one study in which they evaluated the end results in patients between intracholecystic papillary neoplasms and conventional adenocarcinomas of the GB [14]. Zhenfeng Wang et al. also suggested a prognostic nomogram for GBPA [15].

Conclusion

GBPA is a less prevalent subtype of GBC that has a better prognosis than adenocarcinoma. Patient usually presents with abdominal pain and fever. It is unusual for it to manifest as a cholecystocolic fistula. On imaging, it appears as an intraluminal mass/thickened GB wall. Histopathology plays a pivotal role in the diagnosis of these entities by identifying the pattern of the tumor and classifying it further into distinct subtype, which aids the clinician in deciding an accurate treatment plan for the patient.

Data Availability

All data published in article and information available in institute.

Code Availability

NA.

References

Henson DE, Albores-Saavedra J, Corle D. Carcinoma of the GB Histologic types, stage of disease, grade, and survival rates. Cancer. 1992;70(6):1493–7.

Lazcano-Ponce EC, Miquel JF, Muñoz N, Herrero R, Ferrecio C, Wistuba II, Alonso de Ruiz P, AristiUrista G, Nervi F. Epidemiology and molecular pathology of GB cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51(6):349–64.

Goldin RD, Roa JC. GB cancer: a morphological and molecular update. Histopathology. 2009;55(2):218–29.

Albores-Saavedra J, Tuck M, McLaren BK, Carrick KS, Henson DE. Papillary carcinomas of the GB: analysis of noninvasive and invasive types. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129(7):905–9.

Wang SJ, Fuller CD, Kim JS, Sittig DF, Thomas CR Jr, Ravdin PM. Prediction model for estimating the survival benefit of adjuvant radiotherapy for GB cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(13):2112–7.

Lee SS, Kim MH, Lee SK, Jang SJ, Song MH, Kim KP, Kim HJ, Seo DW, Song DE, Yu E, Lee SG, Min YI. Clinicopathologic review of 58 patients with biliary papillomatosis. Cancer. 2004;100(4):783–93.

Wan X, Zhang H, Chen C, Yang X, Wang A, Zhu C, Fu L, Miao R, He L, Yang H, Zhao H, Sang X. Clinicopathological features of GB papillary adenocarcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93(27): e131.

Misra S, Chaturvedi A, Misra NC, Sharma ID. Carcinoma of the GB. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4(3):167–76.

Albores-Saavedra J, Murakata L, Krueger JE, Henson DE. Noninvasive and minimally invasive papillary carcinomas of the extrahepatic bile ducts. Cancer. 2000;89(3):508–15.

Albores-Saavedra J, Henson DE, Klimstra D. Tumors of the GB, extrahepatic bile ducts, and ampulla of vater. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2000. Atlas of Tumor Pathology; 3rd series, fascicle 27. (1 of articles 4)

Hoang MP, Murakata LA, Katabi N, Henson DE, Albores-Saavedra J. Invasive papillary carcinomas of the extrahepatic bile ducts: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 13 cases. Mod Pathol. 2002;15(12):1251–8.

Ha GW, Lee MR, Kim JH. Cholecystocolic fistula caused by gallbladder carcinoma: preoperatively misdiagnosed as hepatic colon carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol: WJG. 2015;21(15):4765.

Kuo JY, Jao YT. Gallbladder papillomatosis and cholecystocolonic fistula: a rare combination. Am J Case Rep. 2014;15:466.

Kang JS, Lee KB, Choi YJ, Byun Y, Han Y, Kim H, Kwon W, Jang JY. A comparison of outcomes in patients with intracholecystic papillary neoplasms or conventional adenocarcinomas of the gallbladder. HPB. 2021;23(5):746–52.

Wang Z, Wang L, Hua Y, Zhuang X, Bai Y, Wang H. Development and validation of a prognostic nomogram for gallbladder papillary adenocarcinoma. Front Oncol. 2023;16(13):1157057.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Planning—PS

Conduct—PS, JNB

Reporting—PS, JNB

Concepts and design—JNB

Data acquisition—PS

Data Interpretation—JNB

Manuscript preparation, editing, and review—PS, JNB

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Waivers from Institute Ethics Committee.

Consent to Participate

Obtained from patient. The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient has given her consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published, and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Consent for Publication

Written informed consent taken from patient.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Topical Collection on Surgery

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Saraf, P., Bharti, J.N. Gall Bladder Papillary Carcinoma Presenting as Cholecystocolic Fistula and Metastasizing to Pericholecystic Lymph Node: an Incidental and Rare Finding—a Case Report. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 5, 230 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-023-01571-4

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-023-01571-4