Abstract

Bariatric surgery is of great importance due to the high incidence of morbid obesity. Techniques such as laparoscopic gastric bypass, laparoscopic tubular gastrectomy, and other bariatric techniques with gastrointestinal anastomosis are used for its treatment. The incidence of internal hernias in the late postoperative period after bariatric surgery ranges from 0.4 to 8.8%. As a consequence, there may be obstruction of the lymphatic vessels. Although chylous ascites is a rare pathology in bariatric surgery, several cases have been reported in the literature. We present two cases of patients who presented as a late complication of an internal hernia associated with chyloperitoneum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The increasing prevalence of morbid obesity in Western countries in recent decades has allowed the development of different laparoscopic bariatric surgery techniques.

Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB), laparoscopy tubular gastrectomy (LTG), and other bariatric techniques with gastrointestinal anastomosis are the most widely bariatric surgery techniques in the world. The laparoscopic approach decreases the morbidity and mortality of this surgery and allows for a faster clinical recovery and incorporation into working life. Some complications may appear in the late postoperative period such as the appearance of internal hernias with an incidence between 0.4 and 8.8% [1, 2]. As a consequence of these hernias, an intestinal or vascular obstruction can be produced. Although lymphatic obstruction is less frequent, it is also possible.

The appearance of chylous ascites in patients with a history of bariatric surgery is quite uncommon. However, the literature has reported up to seven cases of patients with a history of bariatric surgery who have presented as a late complication with the appearance of chyloperitoneum associated with an internal hernia [3,4,5,6,7,8].

We present two cases of patients with a history of bariatric surgery who presented as a late complication of an internal hernia associated with chyloperitoneum.

Case Reports

Case 1

We present a 31-year-old woman with a history of single-anastomosis Billroth 2 gastrointestinal bypass surgery, who underwent surgery at another hospital 4 years ago. After surgery there was a significant weight loss of 55 kg.

The patient came to the Emergency Department of our hospital for abdominal pain of 48 h of duration. The pain was located in the mesogastrium, right iliac fossa (RIF), and both lumbar fossae. She was afebrile, without nausea or vomiting and with intestinal transit present.

On examination, the patient was in good general condition, afebrile, hemodynamically stable, conscious, and oriented. The abdomen was soft and compressible, and a tender mass of 5 × 5 cm was felt in the mesogastrium and RIF. The patient had pain on palpation.

In the imaging tests, a suspicion of ileal invagination was identified by abdominal ultrasound (Fig. 1). A group of enlarged lymph nodes forming a lump of size 42 × 8 mm was appreciated in the mesogastric region, which formed the head of the invagination. In addition, a streak of fluid was noticed in the proximity of the lump.

Due to the diagnostic suspicion of an ileoileal invagination, the patient was operated urgently. An internal hernia was identified through the Petersen space during diagnostic laparoscopy. In addition, there was a discrete amount of chylous ascites at the subdiaphragmatic space and in the right paracolic gutter. We reduced completely the small bowel loops that produced the internal hernia through Petersen’s space (Fig. 2) and we closed the Petersen’s space with continuous monofilament suture 2–0 (Fig. 3).

After the intervention the patient had a favorable clinical course, with good tolerance to the oral diet, so that on the third postoperative day she was discharged from the hospital. After that episode, the patient was asymptomatic.

Case 2

We present a 36-year-old woman with a history of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery at another hospital 3 years ago. The patient presented with a late complication of an ulcer at the gastrojejunal anastomosis after medical management.

The patient came to the Emergency Department of our hospital for continuous abdominal pain located in the epigastrium, and right and left hypochondrium, associated with nausea and vomiting. She was afebrile and had intestinal transit.

On examination, the patient was in good general condition, afebrile, hemodynamically stable, conscious, and oriented. The patient had pain to the palpation at generalized way, specially localized at epigastrium. However, she did not have peritoneal irritation.

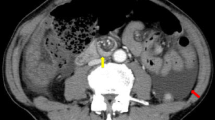

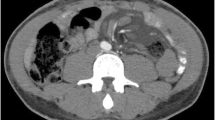

Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen and pelvis revealed transmesenteric internal hernia with minimal free fluid in the pelvis (Fig. 4). Anemia with a hemoglobin level of 10.6 g/dl was observed in the analysis. The rest of parameters were normal.

Due to the diagnostic suspicion of an internal transmesenteric hernia, we decided operate urgently. In the diagnostic laparoscopy, we observed an internal hernia through to the mesenteric gap of the loop foot with almost complete hernia of the entire intestine with twisted root of mesentery (Fig. 5). We also observed abundant amounts of chylous ascites (Fig. 6).

Due to the difficulty of the surgical technique with laparoscopy, we decided to convert to mid-supraumbilical laparotomy, performing complete reduction of the small bowel loops, derotation of the mesentery and closing the mesenteric gap with continuous nonabsorbable monofilament suture 2–0 (Fig. 7).

After that, in the immediate postoperative period, the patient had abdominal painful and subcutaneous edema in the left iliac fossa (LIF). We observed a decrease in hemoglobin levels up to 6.8 g/dL. We performed an abdominal CT angiography, where a hematoma was diagnosed in the left abdominal wall without active bleeding. The patient was clinical and hemodynamically stable, so we decided to manage conservatively with transfusion of red blood cells and intravenous iron.

After that, the patient had a favorable clinical course, with a good oral tolerance and normalization in the hemoglobin values. Subsequently, the patient was discharged from de hospital on the sixth postoperative day.

Discussion

Chylous ascites or chyloperitoneum is defined as the accumulation of milky peritoneal liquid having a triglyceride level higher than 200 mg/dl; however, few authors consider a cut-off value of triglycerides to be 110 mg/dl [9,10,11,12].

It is produced due to leakage or rupture of the thoracic or abdominal lymphatic system due to traumatic injury, neoplasms, or obstruction.

Abdominal neoplasms, lymphatic abnormalities and cirrhosis are the most common etiologies in Western countries. In eastern and developing countries, infectious etiologies such as tuberculosis and filarias are represent in the majority of cases. Other causes of chylous ascites are congenital, inflammatory, postoperative, traumatic, and miscellaneous disorders [9].

Three underlying mechanisms have been proposed:

-

1)

Obstruction of lymphatic vessels by neoplasms, leading to exudation through the wall of the dilated lymphatic vessel or rupture of the vessel. These patients often develop a protein-losing enteropathy that leads to chronic diarrhea (steatorrhea), malabsorption, and malnutrition.

-

2)

The exudation of the chyle through the walls of dilated retroperitoneal lymphatic vessels, for example in congenital lymphangiectasia or thoracic duct obstruction.

-

3)

Acquired obstruction of the thoracic duct by trauma or surgery, causing a direct leakage of chylous fluid through a lymphoperitoneal fistula [9, 13, 14].

The most frequent clinical feature of chylous ascites is the progressive and painless abdominal distension, with a long time of evolution, although in patients with a history of abdominal surgery may present an acute onset. Other common symptoms are weight gain or loss, and dyspnea due to it increased with intra-abdominal pressure, nonspecific abdominal pain, diarrhea and steatorrhea, malnutrition, edema, nausea, enlarged lymph nodes, early satiety, fevers, and night sweats [10, 13, 15]. However, in chylous ascites after bariatric surgery, the clinical course is usually more insidious.

The diagnosis of chyloperitoneum after bariatric surgery is based on high diagnostic suspicion, supported by the finding of free fluid in abdominal ultrasound and CECT abdomen and pelvis. However, the lymphogammagraphy is the main study because it allows us to identify the lymphatic anatomy and the possible points of lymphoperitoneal fistula [16, 17]. The diagnostic confirmation requires a diagnostic paracentesis and analysis of the chylous, which usually shows high concentrations of triglycerides, between 110 and more than 200 mg/dL, according to authors: an alkaline pH, proteins between 2.5 and 7 g/dL, and cells with predominance of lymphocytes [9,10,11,12].

Currently, there are few reported cases of chyloperitoneum associated with internal hernia after LRYGB, three of them with the appearance of an internal hernia through the mesenteric defect of the jejunal anastomosis [3, 5, 7]. There is only one reported case of chyloperitoneum associated with an internal hernia through Petersen’s space after a LRYGB [8]. Two cases of chyloperitoneum have also been reported in patients with a history of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding [4]. Another case of chyloperitoneum associated with gastric neoplasia in patients with a history of LRYGB has also been reported [6].

Treatment of chyloperitoneum must be individualized according to the cause that originates it, usually based on parenteral nutrition associated with somatostaine, octreotide, or orlistat and a low-fat diet with medium-chain triglycerides since their absorption is direct to the bloodstream without passing through the lymph. In some cases, surgery may be necessary, but not as a first option [18].

In the above-presented cases, the clinical picture was not suggestive of chyloperitoneum, but of ileoileal invagination and internal hernia, so diagnostic-therapeutic laparoscopy was performed. We detected incidentally the chyloperitoneum associated with an internal hernia through Petersen’s space and to an internal hernia through to the mesenteric gap of the loop foot with almost complete hernia of the entire intestine with twisted root of mesentery.

Conclusion

In a patient with a history of bariatric surgery who comes to the emergency room with abdominal pain, we must take into account the differential diagnosis of internal hernia, since this is one of the possible late complications. That implies a surgical urgency because it can compromise the patient’s life. The performance of an urgent therapeutic diagnostic laparoscopy must be paramount, although we can also identify associated incidental chylous ascites.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Higa K, Boone K, Arteaga González I, López-Tomasseti Fernández E. Cierre mesentérico en el bypass gástrico laparoscópico: técnica quirúrgica y revisión de la literatura. Cir Esp. 2007;82(2):77–88.

Al Harakeh A, Kallies K, Borgert A, Kothari S. Bowel obstruction rates in antecolic/antegastric versus retrocolic/retrogastric Roux limb gastric bypass: a meta-analysis. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:194–8.

Hidalgo J, Ramirez A, Patel S, Acholonu E, Eckstein J, et al. Chyloperitoneum after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB). Obes Surg. 2010;20(2):257–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-009-9939-y.

Nau P, Narula V, Needleman B. Successful management of chyloperitoneum after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in 2 patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7(1):122–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2010.02.037.

Hanson M, Chao J, Lim R. Chylous ascites mimicking peritonitis after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8(1):e1-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2010.07.014.

Capristo E, Spuntarelli V, Treglia G, Arena V, Giordano A, Mingrone G. A case report of chylous ascites after gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;29:133–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.10.077.

Zaidan L, Ahmed E, Halimeh B, Radwan Y, Terro K. Long standing biliary colic masking chylous ascites in laparoscopic roux-en-Y gastric bypass; a case report. BMC Surg. 2018;18(1):43.

Del Valle RS, González Valverde F, Tamayo Rodríguez M, Medina Manuel E, Albarracín M-B. Incidental chyloperitoneum associated with Petersen’s hernia in a patient operated by laparoscopic gastric bypass. Cir Esp. 2019;97(6):351–3.

Cárdenas A, Chopra S. 2002 Chylous ascites. Am J Gastroenterol [Internet]. Sep;97(8):1896–900.

Press O, Press N, Kaufman S. Evaluation and management of chylous ascites. Ann Intern Med. 1982;96(3):358–64.

Runyon B, Hoefs J, Morgan T. Ascitic fluid analysis in malignancy-related ascites. Hepatology. 1988;8(5):1104–9.

Jüngst D, Gerbes A, Martin R, Paumgartner G. Value of ascitic lipids in the differentiation between cirrhotic and malignant ascites. Hepatology. 1986;6(2):239–43.

Browse N, Wilson N, Russo F, Al-Hassan H, Allen D. Aetiology and treatment of chylous ascites. Br J Surg. 1992;79(11):1145–50.

Bhardwaj R, Vaziri H, Gautam A, Ballesteros E, Karimeddini D, Wu G. Chylous ascites: a review of pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2018;6(1):1–9.

Aalami O, Allen D, Organ C. Chylous ascites: a collective review. Surgery. 2000;128(5):761–78.

Pui M, Yueh T. Lymphoscintigraphy in chyluria, chyloperitoneum and chylothorax. J Nucl Med. 1998;39(7):1292–6.

Archimandritis A, Zonios D, Karadima D, Vlachoyiannopoulos P, Kiriaki D, Hatzis G. Gross chylous ascites in cirrhosis with massive portal vein thrombosis: diagnostic value of lymphoscintigraphy. A case report and review of the literature. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15(1):81–5.

Weniger M, D’Haese J, Angele M, Kleespies A, Werner J, Hartwig W. Treatment options for chylous ascites after major abdominal surgery: a systematic review. Am J Surg. 2016;211(1):206–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.04.012.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have read and approved the manuscript and meet authorship criteria, agreeing with the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

None needed as a case report.

Consent to Participate

Oral informed consent was obtained to the submission of the case report to the journal.

Consent for Publication

Oral informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Azorín, M.C., Segura, M.J., Gómez, M. et al. Incidental chylous ascites associated with internal hernia after bariatric surgery: a case report. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 3, 2701–2706 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-021-01075-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-021-01075-z