Abstract

Familial Alzheimer’s disease (AD) accounts for less than 1% of the total cases of AD and is characterized by a cognitive decline typically initiated before the age of 65 with a positive familial history, usually with a dominant inherence pattern. A 35-year-old man, whose mother died at the age of 36 with an undetermined rapidly progressive dementia, developed memory impairment and depression at the age of 33 followed by spatial disorientation, behavioral changes, and hallucinations at the age of 35. His neurological examination revealed bradyphrenia with a poor perseverative speech, executive dysfunction, dyscalculia, and bilateral frontal release signs. Blood analysis and brain MRI were normal; however, cerebrospinal fluid showed an elevated phosphorylated tau/beta-amyloid ratio, and SPECT revealed a global hypoperfusion. Therefore, a genetic testing for autosomal dominant variants of AD was performed, disclosing a presenilin 1 (PSEN1) mutation, Pro117Leu, which confirms the diagnosis of familial Alzheimer’s disease. One year later, he had developed severe cognitive impairment with pyramidal and extrapyramidal signs, regardless of donepezil therapeutic regimen. PSEN1 mutation is the most common cause of familial AD and, compared to the other mutations, is associated with the youngest age of onset and with the presence of atypical neurological signs. To our knowledge, this is one of the cases with younger age of onset described in the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of neurodegenerative dementia, responsible for an elevated morbidity and mortality all over the world. Its prevalence increases with age; however, this disorder has been increasingly recognized in the population under 65 years old, being nowadays classified as early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (EOAD) and accounting for 5–6% of all AD cases [1].

One of the most striking differences between early-onset and late-onset AD is the stronger genetic background of the first one: on the one hand, there is a higher polygenic susceptibility, and on the other hand, there are specific gene mutations in about 11% of the patients, most of them with an autosomal dominant pattern of inherence and consequently positive familial history [1,2,3].

Considering the second group, 50% of cases are related to mutations in one of three genes: presenilin 1 (PSEN1), presenilin 2 (PSEN2), and amyloid precursor protein (APP). All of these genetic alterations lead to an impairment on amyloid metabolism, with a subsequent accumulation of β-amyloid 42 (Aβ42) peptides [2, 3].

In addition to a higher genetic background, EOAD is also reported to have a more aggressive course and rapid progression, as well as a higher mortality rate [1]. Herein, we report a case of AD in the context of a PSEN1 mutation with an age of onset of 33 years old and atypical neurological features.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old Caucasian man, working as a gardener with 10 years of education, developed depression and progressive memory decline at the age of 33. Although he was medicated with escitalopram 20mg id and mexazolam 1mg id, there was no clinical improvement, and he developed significant behavioral changes (lack of empathy, aggressiveness, and suicidal ideation) which led to the substitution of escitalopram with paroxetine. By the age of 35, he presented additional spatial disorientation and hallucinations, both visual and auditory.

At the first consultation, his neurological examination revealed bradyphrenia with a poor perseverative speech, executive dysfunction, dyscalculia, and bilateral frontal release signs. He did not disclose any cranial nerves alterations or pyramidal, extrapyramidal, and cerebellar signs.

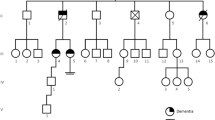

His past medical history was unremarkable; however, his mother died at the age of 36 with the diagnosis of rapidly progressive dementia of unknown etiology: according to the patient’s sister, she began with behavioral changes and executive dysfunction at approximately the same age as the patient and evolved to a marked cognitive impairment and premature death. No other relatives showed signs of neurodegenerative disorders (his mother was an only child, his sister was asymptomatic, and the patient did not have children).

Extensive investigation revealed normal blood work-up, brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination. However, single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) shown a global hypoperfusion, predominantly in the left fronto-temporo-parietal region, and an elevated phosphorylated tau/β-amyloid ratio in CSF.

Therefore, a genetic testing for autosomal dominant variants of AD was performed, disclosing a PSEN1 mutation (Pro117Leu), which confirmed the diagnosis of familial Alzheimer’s disease, and he was started on a donepezil therapeutic regimen (10mg id).

One year later, he was completely dependent by a severe cognitive decline with memory impairment, aphasia, and apraxia. He had developed seizures and was bedridden with pyramidal (spastic tetraparesis) and extrapyramidal signs (akinetic-rigid Parkinsonism). On the last consultation, his father revealed that the clinical evolution was similar to the patient’s late mother and that he had to be institutionalized in a nursing home.

Discussion and Conclusions

Presenilin 1 mutation is the most common cause of genetic EOAD, with over 220 pathologic mutations already described [2, 3]. These patients share specific features that allow us to distinguish them from other genetic causes of AD: they have the youngest age of onset, with some patients starting their manifestations in their 20s, and characteristically present atypical neurological signs [3].

The specific mutation found in our patient, Pro117Leu, was first described in a Polish family in 1998 [4], and although it was only reported in 6 patients in the literature, the features were quite consistent in the majority: all of them reported memory loss, and more than half also presented mood disturbances and non-fluent aphasia. Considering atypical neurological signs, myoclonus and Parkinsonism were commonly found, although it was also described as seizures, cerebellar signs, and psychosis [5].

In the case reported, our patient presented with memory complaints and mood disturbances at the age of 33. He was initially managed considering a psychiatric condition, with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), with no objective benefit. By the time he was observed in a neurology consultation, he displayed involvement of almost every cognitive domain: visuospatial, language, executive, calculation, and psychiatric, which is usually seen in EOAD [1, 6].

The family history was helpful; however, it was necessary to go beyond the initial description of possible Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in the patient’s mother and review the age of onset and clinical presentation, similar to the reported case, and evolution. However, an autosomal dominant pattern of inherence is always difficult to determine when there is only involvement of one family member, even in a small family as this one.

The imaging study with MRI was unremarkable in our patient, in opposition to the variable degree of atrophy described in other patients with the same mutation [5]. Nonetheless, SPECT shown a global hypoperfusion, predominantly in the left fronto-temporo-parietal region, different from the typical temporo-parietal hypoperfusion described in EOAD [1], which can probably be related to the early involvement of non-mnesic domains, namely executive and language.

With time, our patient progressed rapidly to a severe cognitive impairment and developed atypical neurological signs, such as seizures, pyramidal, and extrapyramidal signs, usually described in the EOAD [1, 2, 6].

In conclusion, we reported a patient with familial Alzheimer’s disease secondary to a mutation on PSEN1 (Pro117Leu) with age of onset at 33 years old, one of the youngest described in the literature. The rapid progression and atypical neurological signs, even in an early age, should always make us consider this diagnosis.

References

Mendez MF. Early-onset Alzheimer disease and its variants. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019;25(1):34–51. https://doi.org/10.1212/CON.0000000000000687.

Ryan NS, Nicholas JM, Weston PSJ, Liang Y, Lashley T, Guerreiro R, et al. Clinical phenotype and genetic associations in autosomal dominant familial Alzheimer's disease: a case series. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(13):1326–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30193-4.

Gao Y, Ren RJ, Zhong ZL, Dammer E, Zhao QH, Shan S, et al. Mutation profile of APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 in Chinese familial Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;77:154–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2019.01.018.

Wisniewski T, Dowjat WK, Buxbaum JD, Khorkova O, Efthimiopoulos S, Kulczycki J, et al. A novel Polish presenilin-1 mutation (P117L) is associated with familial Alzheimer’s disease and leads to death as early as the age of 28 years. NeuroReport. 1998;9(2):217–21. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001756-199801260-00008.

Rocha AL, Costa A, Garrett MC, Meireles J. Difficult case of a rare form of familial Alzheimer’s disease with PSEN1 P117L mutation. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;13:11(1). https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2018-226664.

Shea YF, Chu LW, Chan AO, Ha J, Li Y, Song YQ. A systematic review of familial Alzheimer’s disease: differences in presentation of clinical features among three mutated genes and potential ethnic differences. J Formos Med Assoc. 2015;115(2):67–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2015.08.004.

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in the literature review and drafting of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

All procedures in this clinical case were performed in accordance with local and international ethical standards.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Medicine

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Raimundo, R., Jesus, R. & Veiga, A. Familial Alzheimer’s Disease due to Presenilin 1 Mutation at the Age of 33: a Case Report. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 3, 2021–2023 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-021-00982-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-021-00982-5