Abstract

Enchondroma is a common benign bone tumor primarily of the appendicular skeleton and distal upper extremities. Although generally asymptomatic, enchondromas share radiographic and histologic characteristics with the more malignant chondrosarcoma, thereby necessitating further investigation. We report the case of a 31-year-old male who presented with a mid-back deformity with imaging notable for a large mid-thoracic spinous process lesion. Gross and microscopic pathology were consistent with an enchondroma of the thoracic spine. A review of the literature to characterize the treatment approaches and outcomes for this condition was performed. Though uncommon, enchondroma is an important diagnostic consideration in the workup of bony spinous process lesions. Excellent outcome is achievable with surgical resection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Enchondroma is a neoplasm of intramedullary cartilage most common in the hand or wrist of children and young adults and second most common benign chondral tumor comprising 12–24% of benign bone tumors [4, 22]. This relatively common lytic bone lesion is rarely found in the axial skeleton, with limited reports in the literature. Here, we present the first case in North America of enchondroma of the thoracic spine.

Case Presentation

A 31-year-old man with no medical history presented to our institution’s clinic with a slow growing lesion of his midline thoracic spine causing an obvious lump under the skin. The lesion was noted 2 years prior and was referred for continued growth. The lesion was not associated with pain or tenderness.

Physical examination revealed a firm, immobile, palpable lesion between spinous processes located on the high thoracic spine without erythema or fluctuance. Neurological exam was unremarkable.

Neuroimaging

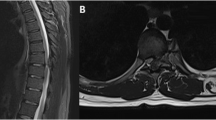

CT (Fig. 1) demonstrated a well-defined 4.5 cm X 4.0 cm partially ossified exophytic dorsal paraspinal lesion arising from the outer cortex of the T3 spinous process. Peripherally dense calcification and/or ossification was present in a ring and arc configuration, typically described in enchondromas. There was no destruction of the adjacent T4 spinous process or periosteal reaction. MRI findings (Fig. 2) were consistent with peripheral calcification and/or ossification and central fatty bone marrow signal intensity. Mild surrounding soft tissue edema and inflammation were present, without evidence of associated soft tissue mass.

Sagittal non-contrast CT (A, B) and axial CT (C, D) demonstrate a heterogenous exophytic dorsal paraspinal mass originating from the outer cortex of the T3 spinous process. Peripherally dense calcification/ossification are present in a ring and arc configuration typically described in enchondromas (long arrows, A & B). Central relative low density reflects internal fatty marrow and cellular elements (short arrows, C & D). The margins of this mass are well defined and sharp and a very short zone of transition with the normal bone of the spinous process is noted

Sagittal T1-weighted (A), sagittal T2 weighted STIR (B) and axial T2 weighted (C) non-contrast MRI sequences of the thoracic spine demonstrate a heterogenous exophytic dorsal paraspinal mass originating from the T3 spinous process. Peripherally T1 and T2 hypointensity reflects dense calcification/ossification (long arrows). Central T1 and T2 hyperintensity reflects fatty marrow and cellular elements (short arrows). There is mild surrounding soft tissue edema and inflammation present (arrowhead). No associated soft tissue mass is evident

The overall findings were consistent with a low grade osteochondromatous process with the characteristic ring and arc calcification supportive of an enchondroma.

Surgical Resection

The patient underwent T3/4 laminectomy and resection of bony tumor from a posterior approach in the prone position. A subperiosteal dissection was performed to expose the posterior elements of T3 and T4. A large fungating calcified bony lesion was identified between the T3 and T4 spinous processes extending down to and partially involving the lamina (Fig. 3a). Using a high-powered drill and Leksell rongeurs, the lesion and lamina were resected piece-meal without obvious residual lesional tissue remaining. Care was taken to perform as minimal a laminectomy as possible to preserve facet joints and posterior structural elements while ensuring gross total resection.

(A) Fungating calcified lesion identified between the T3 and T4 spinous processes extending down to and involving the lamina. Specimen stained with hematoxylin and eosin: (B) Low power (4x) slides demonstrate predominantly cartilage with extensive calcification and ossification at the periphery of the mass. (C) High power (20x) slides demonstrate cartilaginous lacunae containing chondrocytes without significant cytologic atypia

Pathology

On gross examination, the specimen was a 5.5 × 4.5 × 3.0 cm aggregate of tan-pink, irregular bony and soft tissue fragments without discrete masses or lesions. Histologically the biopsy sample revealed a well-differentiated lesion composed of cartilage with extensive internal calcification (Fig. 3b). In some fragments, the lesion demonstrated a nodular growth pattern arising between the periosteum and bone. In many fragments, endochondral ossification was identified with cartilaginous lacunae containing chondrocytes without significant cytologic atypia (Fig. 3c). The overall findings suggest a long-standing, low-grade cartilaginous lesion with endochondral ossification consistent with enchondroma.

Post-Operative Course

The postoperative course was unremarkable, and the patient was discharged home on postoperative day one without complications. Post-operative CT confirmed gross total excision with preservation of the normal thoracic kyphosis and no violation of the facet joints (Supplemental Fig. 1).

The patient was seen in clinic on postoperative day 14 with no further complaints or concerns with plans for surveillance imaging and follow-up in 1 year.

Discussion

Primary tumors of the bone offer a wide differential diagnosis. According to the 2013 WHO classification, the initial branch point separating large categories of primary bony lesions rests on the cell of origin or histogenesis. Generally, primary bone lesions arise from bone-forming tumors, cartilage-forming tumors, fibrous bone lesions, or bone marrow tumors (Table 1) [There are a variety of primary bone tumors or lesions not included here and grouped in additional smaller categories, including aneurysmal bone cysts, chordoma, giant cell tumors, etc.] [4, 17, 22].

Cartilage forming tumors are comprised mostly of benign lesions, including chondroblastoma, chondromyxoid fibroma, enchondroma, juxtacortical, and chondroma, while the malignant cartilage forming tumor is chondrosarcoma. Benign chondrogenic tumors are the most common benign primary bone tumors. Within this category, enchondromas, second only to osteochondroma, are the most common osseous neoplasms [4, 20, 22]. Enchondromas have a peak incidence in ages 10–40 years, yet since many patients are asymptomatic the true prevalence is unknown [4, 12, 13]. Brien et al. reviewed 3067 primary bone tumors and lesions, and reported enchondroma in 19.7% of all cartilaginous tumors and in 7.7% of all cases [2]. Although enchondromas tend to occur as solitary lesions, there are two enchondromatosis syndromes, Ollier disease, and Maffucci syndrome, associated with multiple enchondromas found in unilateral long bones or associated with soft tissue hemangiomas, respectively. These enchondroma syndromes highlight the risk of sarcomatous degeneration with rates as high as 25% in Ollier and Maffucci, whereas isolated enchondroma malignant transformation to chondrosarcoma, usually low-grade, is rare [6, 14, 19].

Most often occurring in the appendicular skeleton, enchondromas are the most common benign bone tumor of the hand and wrist (40–65%), followed by the major long bones (25%)—femur, humerus, tibia, in descending order—and the small bones of the feet (7%) [4, 8]. Other body sites of enchondroma are uncommon, and they are only very rarely found in the spine [4, 8, 10, 14]. There are only a few documented cases of spinal enchondroma [7, 9,10,11, 23].

The diagnosis of benign cartilaginous bone tumors, including enchondroma, is multifactorial and when uncertain requires tissue diagnosis. Chondrosarcoma (8–17% of bone tumors) can be histologically and radiographically difficult to distinguish from enchondroma [5]. Histologically, enchondroma consists of neoplastic chondrocytes among a hyaline-myxoid background, with focal calcifications and rare cellular mitoses and minimal nuclear atypia, whereas chondrosarcoma has similar features and is locally invasive [1, 10, 11]. Radiographically, the only established differentiating characteristic is size—enchondroma < 5 cm and chondrosarcoma > 4 cm [3, 15, 20, 22]. Clinically, 95% of patients with chondrosarcoma have associated pain, while enchondroma patients are generally asymptomatic [16, 18, 21].

Conclusions

Given the aforementioned diagnostic dilemma and possibility of malignant transformation, surgical excision is generally recommended, especially in the presence of a symptomatic lesion greater than 4 cm. Overall, as this case demonstrates, the surgical goal is to determine a final diagnosis and achieve a gross total resection to eliminate the risk of sarcomatous degeneration.

References

Akiyama T, Yamamoto A, Kashima T, Ishida T, Shinoda Y, Goto T, et al. Juxtacortical chondroma of the sacrum. J Orthop Sci. 2008;13(5):476–80.

Brien EW, Mirra JM, Kerr R. Benign and malignant cartilage tumors of bone and joint: their anatomic and theoretical basis with an emphasis on radiology, pathology and clinical biology. I The intramedullary cartilage tumors. Skeletal Radiol. 1997;26(6):325–53.

Campanacci M, Bertoni F, Bacchini P (1990) Bone and soft tissue tumors. 455–505.

Douis H, Saifuddin A. The imaging of cartilaginous bone tumours. I Benign lesions. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41(10):1195–212.

Eefting D, Schrage YM, Geirnaerdt MJA, Le Cessie S, Taminiau AHM, Bovée JVMG, et al. Assessment of interobserver variability and histologic parameters to improve reliability in classification and grading of central cartilaginous tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(1):50–7.

El Abiad JM, Robbins SM, Cohen B, Levin AS, Valle DL, Morris CD, et al. Natural history of Ollier disease and Maffucci syndrome: patient survey and review of clinical literature. Am J Med Genet A. 2020;182:1093–103. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.61530.

Erten SF, Koçak A, Mizrak B, Kutlu R, Colak A. An end-plate chondroma mimicking calcified lumbar disc herniation. A case report and review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev. 1999;22(2–3):145–8.

Flemming DJ, Murphey MD. Enchondroma and chondrosarcoma. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2000;4(1):59–71.

Gaetani P, Tancioni F, Merlo P, Villani L, Spanu G, Baena RR. Spinal chondroma of the lumbar tract: case report. Surg Neurol. 1996;46(6):534–9.

Guo J, Gao J-Z, Guo L-J, Yin Z-X, He E-X. Large enchondroma of the thoracic spine: a rare case report and review of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):155.

Kim DH, Nam KH, Choi BK, Han I. Lumbar spinal chondroma presenting with acute sciatica. Korean J Spine. 2013;10(4):252–4.

Kransdorf MJ, Peterson JJ, Bancroft LW. MR imaging of the knee: incidental osseous lesions. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2007;15(1):13–24.

Levy JC, Temple HT, Mollabashy A, Sanders J, Kransdorf M. The causes of pain in benign solitary enchondromas of the proximal humerus. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;431:181–6.

McLoughlin GS, Sciubba DM, Wolinsky J-P. Chondroma/chondrosarcoma of the spine. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2008;19(1):57–63.

Mulder JD, Kroon HM, Schutte HE, Taconis WK (1993) Radiologic Atlas Of Bone Tumors 749.

Murphey MD, Walker EA, Wilson AJ, Kransdorf MJ, Temple HT, Gannon FH. From the archives of the AFIP: imaging of primary chondrosarcoma: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2003;23(5):1245–78.

Picci P, Gambarotti M, Righi A. Classification of primary bone lesions. In: Picci P, Manfrini M, Donati DM, Gambarotti M, Righi A, Vanel D, Dei Tos AP, editors. Diagnosis of musculoskeletal tumors and tumor-like conditions: clinical. Cham: radiological and histological correlations - The Rizzoli Case Archive. Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 11–2.

Reith JD (2018) Chapter 40 - bone and joints. In: Goldblum and lamps (ed) Rosai And Ackerman’s Surgical Pathology - 2 Volume Set, Eleventh. International Edition (2018), Philadelphia, PA, pp. 1740–1809.

Silve C, Jüppner H. Ollier disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:37.

Unni KK. Tumors of the bones and joints. AFIP Atlas of Tumor Pathology: Tumors of the Bones & Joints. Amer Registry of Pathology; 2005. p. 249–53.

Varma DG, Ayala AG, Carrasco CH, Guo SQ, Kumar R, Edeiken J. Chondrosarcoma: MR imaging with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1992;12(4):687–704.

Walden MJ, Murphey MD, Vidal JA. Incidental enchondromas of the knee. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190(6):1611–5.

Willis BK, Heilbrun MP. Enchondroma of the cervical spine. Neurosurgery. 1986;19(3):437–40.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper. All named authors participated in critical writing/revision and analysis and meet full criteria for authorship.

Patient Consent

The patient has consented to the submission of this case report to the journal.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Surgery

Supplementary Information

Supplemental Fig. 1

Representative post-operative axial (left) and sagittal (right) non-contrast CT images, status post interval partial thickness bilateral laminectomies at T3/4 and gross total resection of the enchondroma. There is preservation of normal thoracic kyphosis without spondylolisthesis (PNG 780 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goldberg, J.L., Carnevale, J.A., Link, T.W. et al. Enchondroma of the Thoracic Spine: Case Report and Review of Literature. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 3, 739–743 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-021-00759-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-021-00759-w