Abstract

From the perspective of family life cycle, and drawing on data from national population censuses, and one percent population surveys, as well as other relevant resources, this paper examines the changing trajectory of the Chinese family over the past 70 years, particularly since the reform and opening-up in 1978. It has been found that the changes of family life cycle are embedded in the broad context of socioeconomic transformation and demographic transition. The delayed age at first marriage has postponed the onset of family formation; the substantially reduced number of children has shortened the length of family expansion, but increased the time span of family stability and empty-nest, and the family is becoming old due to low birthrate and longer life expectancy. In other words, the six-stages associated with the traditional family life cycle has been largely reshaped in the past 70 years, which in turn substantially compromised traditional family functions. In the new era, therefore, it is necessary for the government to provide family-friendly policies in childcare and elderly support in order to fill in the gap in family-oriented public services, and to improve the potentials of long-term development of Chinese families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

As a basic social unit and one of the pillars of society, the family organization has never been independent or isolated from societal change. With industrialization and urbanization, it has inevitably undergone changes. In the US and other western countries, for example, norms toward marriage and the family have been reshaped, and the proportion of traditional conjugal family has largely declined: in 1960, nuclear family with children younger than 18 years of age accounted for 45%, while it was only 23.5% in 2000; conversely, over half of American families were remarried family, and between the year 1900 and 1950, the number of single-parent family had tripled, and further doubled in the past half century (Benokraitis 2014). The idea that convergence toward the nuclear family of the West (Goode 1963) has not occurred (Cherlin 2017). Also, while scholars have long portrayed families in East Asia as different from those in the West (Reher 1998), and there is a cultural force that holds the family a solidified system during rising modernization in economy and society (Yang and Li 2009), family change have been similarly pronounced in East Asia (Raymo et al. 2015).

Family in China has also experienced substantial and continuous changes. In the past century, Chinese family had encountered three drastic internal and external shocks: The May 4th Movement in 1919, the chaos of Cultural Revolution from the late 1960s through 1970s, and the socioeconomic reform and demographic transition since 1978. What do the changing economic, demographic, and social landscapes mean for the family? How is the family reconfigured by societal transformation? Has the Chinese family declined with societal change or is the family sufficiently resilient to change? How has the family adjusted itself to adapt or accommodate to macro-level transformation?

This paper attempts to examine the Chinese family in various ways in the past half century, particularly these recent 40 years by situating the family organization into the broad social, economic and demographic contexts. We focus on the changes of family life cycle and their consequences for family relations and family functions. By doing so, it contributes to our understanding of how the family responds to changes in the public arena, and how it may affect the wellbeing of family members.

Over the past 70 years since the founding of People’s Republic of China, the changes in political context, economic structure, sociocultural traditions, as well as demographic characteristics have jointly brought about dramatic shocks and continuous challenges to Chinese families. As the connection locus between individuals and society, families at different stages of family life cycle have different demands for public services and social governance, and whether such demands can be met has a direct impact on the well-being and development potential of the family. The changes in families, as a basic unit of society, will in turn trigger social changes. So, how have the Chinese families changed in the past 70 years? This question can be answered from multiple perspectives. We, in this paper, adopt the perspective of family life cycle, and utilize data from national population censuses and one% population surveys, as well as other relevant sources to examine the changes in Chinese families over the past 70 years, particularly since the reform and opening-up.

2 Macro background of family change

China has witnessed an extraordinary transformation over the past three decades: from centrally-planned and self-sufficient economy to market-based and global economy; from closed-door policy to opening to the outside world; from authoritarian governments to more democratic governments and peaceful political transitions; from rural-based populations to urban majorities, and from high fertility to low fertility. As society modernizes, women get married later and bear fewer children and people live longer and healthier lives. In turn, decreased fertility has implications for modernization and urbanization process, as well as intergenerational reciprocity. These factors would no doubt reshape family life cycle (Yang and He 2014).

2.1 Demographic transition

China's demographic transition is not a spontaneous process, but the direct result of the restrictive family planning programs and policy. Fertility and family change are synchronized during the demographic transition (Pesando et al. 2018). In 1953, China's TFR was more than 6, and the CBR was 37 per thousand. In 1982, the former fell to 2.8, the latter reduced to 22.3 per thousand. In 1990, these two values were further reduced to 2.35 and 21.1 per thousand, respectively, and kept reducing over time. According to the 2010 national population census, they were 1.18 and 12.1 per thousand (Yang and He 2014), respectively. In such demographic context, all aspects of the family have been affected. For example, if a child had few brothers and sisters, he may feel the obligation to co-reside with parents; conversely, if a child had more siblings, especially male siblings, his pressure to co-reside with their parents will be largely reduced (Hirschman and Minh 2002). In other words, a higher fertility rate might be associated with a higher rate of nuclear family, and vice versa (Yang and Short 2007).

Family change depend largely on how long people live. Historically, life expectancy was relatively short, and most parents could not survive until their great grandchildren were born, and some scholars argue that the phenomenon of four or five generations living together under the same roof was rare. However, life expectancy has increased significantly today, 76.34 years old in 2015 (National Bureau of Statistics 2015), for example. Hence, it is possible for three or four generations to co-reside. At the household level, having fewer children while living longer also contribute to a higher proportion of families with at least one people aged 60 or over and a higher proportion of empty nest family, which further reshape traditional family structure.

In the past three decades, China has witnessed a huge wave of migration. The impact of migration on the family is multifaceted. On the one hand, due to the structural and institutional constraints at the place of destination, many family members are unable move together, which widens the geographic distance between family members, and splits nuclear family members. It also generates numerous left-behind families. On the other hand, in addition to improving family economy, geographic mobility may expand migrants’ view to the outside world, accelerate their self-independence and autonomy, weaken their relationship to other family members; it may also weaken parental control over their children, and change migrants, particularly younger ones’ norms toward marriage and the family.

2.2 Modernization and economic development

The modernization theory argues that, in the process of industrialization and urbanization, the family size and structure will be reduced with the development of economy and society, and extended family will be replaced by and converge towards nuclear family (Goode 1963; McDonald 1992).

In the process of modernization and urbanization, individuals have better opportunities in non-agricultural work, women included. This has enabled women to be economic independent, which undoubtedly affect their norms towards marriage and the family, as well as family practice, and eventually affect family life cycle.

Industrialization and urbanization have brought about rapid pace of the economic growth in past 3 decades in China, which yields multifaceted impacts on the family, including family size, living arrangements and other aspects of family structure (Wang 2015). The influence of economic development on family structure can be observed in two ways. On one hand, in more advanced areas, migration will be less popular, and family members are more likely to co-reside, and thus there are more complex families. However, the opposite situation may also occur, that is, in such areas, people's living standard and housing conditions are also better improved, the sense of self-independence and autonomy more enhanced, so as to promote more small families. On the other hand, in less developed areas, people tend to migrate for better economic and other life opportunities, which consequently, yields split households and brings about various new types of family, e.g., left-behind families and skip-generational families.

2.3 Social policy and public service

Associated with urbanization and modernization are the emergence and improvement of social policies and public services towards the family. One of the greatest achievements of new China is the greatly improved level of education among the Chinese people. In 1964 the illiteracy rate of China's population was as high as 32.3%, while it was only 4.1% in 2010, with a 28.2 percentage-points drop over 40 years. On the contrary, the proportion of people with college education rose from less than 0.4% in 1964 to 12.0% in 2010, with an increase of more than 11 percentage-points. At the same time, the enrollment rate among all levels of education also increased: the enrollment rate of primary school, middle school and high school between 1990 and 2010 increased by 24.1, 46.9 and 56 percentage-points (Yang and He 2014), respectively. The improvement of education would have a profound impact on the family in all aspects. For example, with the expansion of public education, more and more young people go to school away from their natal families, which enlarges the spatial distance between parents and children, enhance their life opportunities, and, as in migration, will also promote the sense of self-independence and autonomy, weakening the control of parents over their offspring (Hirschman and Minh 2002). This in turn will cultivate the desire of pursuing free marriage, postponement of the age of first marriage and childbearing.

Family formation and family building are influenced not only by structural forces, but more importantly, by the restrictive fertility policy in the Chinese context. The so-called “one-child policy” has given birth to smaller family size, simplified family structure and family relations, and "4-2-1" family structure (Guo et al. 2002). Since 1980, the size and proportion of one-child families, especially urban areas, has dramatically increased. Only 25.18% of urban women aged 50–59 had both a son and a daughter, 40.60% of them had only a son, and 30.48% of them had only a daughter (Wang 2017). After 2000, the birth control policy still have had profound impacts on urban household structure (Wang 2020). While the restrictive fertility policy directly constrained people's fertility desire and behavior, it remains uncertain how the universal two-child policy will affect family structure.

Changes in family structure demand public service and public welfare for the family, which in turn, facilitate further changes in the family. In traditional agricultural society, the family is not only the social unit of production, but also the unit of resource redistribution, making arrangements for family members to engage in economic activities and household obligations. Contemporarily, a large number of women has participated in outside work, which puts forward a strong demand for public services and public welfare. Public childcare, education, pension, healthcare, and elderly care, for example, have made great progress, and the relevant welfare system has also been gradually established. The reform of the housing system has significantly improved people's living conditions. Children move out of their parental homes, and form their own nuclear family. All of these would have a huge impact on family organization.

2.4 Technological development and the change of family values

With the rapid development of fertility science and technology, the inseparable situation of "love—sex—childbearing—childrearing" has changed fundamentally, which provides the possibility and necessary conditions for the split of traditional families. In traditional family, the first task of marriage is to have children and carry on the family line, and intimate relationship must give away to this obligation. In the absence of effective contraceptive methods, sexual life will inevitably lead to pregnancy, and thus large family. When public service were absent or inadequate, the family was the primary or only locus of childrearing. Therefore, the four parts cannot be separated, which makes the traditional family stable.

The development of modern fertility science and technology has brought two breakthroughs: the first is the invention of contraceptive technology, which separates sexual life and fertility. People can enjoy their sexual life without worrying about the risk of pregnancy. The second is the invention of artificial conception and tube baby technology, which allows women can get pregnant and have children without getting married. The potential impact of these technologies on marriage and family could be huge.

Research has showed that the acceptance of premarital cohabitation among Chinese youth is increasing (Yuan et al. 2016). The proportion of premarital cohabitation may has risen from 10% in 1990–1999 to about 35% in 2010–2014 (Yu and Xie 2017). However, the impact of cohabitation on the family varies, depending upon whether or not it is considered as an alternative form of marriage. For example, Bradatan and Kulcsar (2008) and Nicole et al. (2015) found that for younger generations, cohabitation seems to be a substitute for marriage (at least before women get pregnant), which means that cohabitation has a significant negative impact on the risk of first marriage. Conversely, premarital cohabitation among Chinese youth is mainly transitional, which improves the risk of first marriage of Chinese youth (Yang and Shi 2019).

In the context of traditional agricultural society, children were the guarantee of old age support and the main source of family happiness (i.e., "the more children, the more merrier"). Having many children was the primary family obligation. However, the family not only wanted more children, but also more sons. Early marriage and early childbearing prolonged women's age of childbearing, together with strong son preference, increased the possibility of having more children, and increase the possibility of forming a large family (Wang 2004). Today, the demand for more children has shifted to the pursuit of high-quality children, and the preference for boys has gradually weakened, leading to much smaller family size. In the context of the universal two-child policy, urban women are facing increasing discrimination in the labor market. Their employment opportunity and job promotion could be further reduced because of having another children or “motherhood penalty.” This may in turn affect women's fertility desire and reduce their willingness to have another child.

How may the above changes affect the Chinese family life cycle in the past 70 years, since the establishment of P. R. China? We now turn to this issue by analyzing empirical data.

3 Family change in China: a perspective of family life cycle

Glick (1947) proposed that, in his influential paper titled "The Family Cycle" published in 1947, the family cycle can be divided into six stages: formation, expansion, stability, contraction, empty-nest and dissolution. Such a division is more suitable in historical times with higher fertility. In the context of demographic transition, modernization and the changes in the attitudes toward marriage and the family, the family cycle perspective meets great challenges, couples without children do not go through these stages, for example. However, it remains an useful framework in understanding family changes, particularly in a more holistic and developmental view.

Given the tremendous family changes, we collapse the family life cycle into four stages: formation, building and stability, contraction and empty-nest, and dissolution, and examine each stage in more detail accordingly.

3.1 Family formation

Family formation starts with marriage. With socioeconomic development, the onset of family formation has been largely postponed. The average age at first marriage was 24 years old for women, while it was 26 years old for men in 2015 (Yang and Wang 2019). However, the proportion of unmarried people aged 35 or above in China is rather low, and the traditional pattern of family formation still remains. Generally speaking, family formation in China has the following unique features.

First, the average age of first marriage is characterized by a N-shape in the past 70 years, regardless for males and females, as Fig. 1 illustrates. According to the National One Per Thousand Population Fertility Sample Survey, conducted by the former National Family Planning Commission in 1982, the average age of first marriage of women rose from 18.57 years old in 1949 to 19.57 years old in 1960, and further to 23.05 years old in 1980, but then dropped to 22.82 years old in 1981. Fang (1987) also found the average age of first marriage of women rose from 18.68 years old in 1950 to 20.19 years old in 1970, and then from 20.29 years old in 1971 to 23.12 years old in 1979. Population census data show that the average age at first marriage in 1980, 1990, 2000 and 2010 was 23.78, 22.79, 24.14, 24.85 years old respectively. It was postponed to about 26.30 years old in 2015 and further postponed in 2018. What behind this pattern are both structural forces and institutional factors. For example, with the improvement of women's education and enhanced socioeconomic status, women would inevitably delay their age of first marriage.

Average age of first marriage between 1949 and 2015. Data source: data of 1949 and 1960 are from the "National One Per Thousand Population Fertility Sample Survey" (“fertility survey” thereafter) organized and implemented by the former State Family Planning Commission in 1982; data of 1950, 1970, 1971 and 1979 are from Fang (1987); data of 1980–2010 are from the sixth census; data of 2015 are from national 1% population survey

In China as in many other developed countries or regions, more and more adults fail to form their own family before the age of 30. Data from the “fertility survey” conducted in 1982 suggest that, taking the age of 18 as the benchmark, the national average rate of early marriage has fallen from 49.3% in 1949 to 18.6% in 1970, and further to 3.8% in 1982. If age 23 is regarded as late marriage for women, then their average late marriage rate has increased from 6.6% in 1949 to 13.8% in 1970, and 52.8% in 1980. National population censuses data depicts that the proportion of unmarried adults aged 20–24 monotonically rise over time. While the proportion of unmarried adults among those aged 25–29 varied at different time periods, it also showed an upward trajectory. Data released by the Ministry of Civil Affairs in 2017 indicated that the proportion of married adults in this age group was only 36.9% among all married couples, suggesting that the age of first marriage has been significantly postponed.

With regard to the proportion of unmarried adults among those over age 30, it remained relatively high in the Chinese standard in certain areas. Beijing, for example, such proportion was 10.3% in 1982 and 7.6% in 1990. However, at the national level, the proportion of unmarried was less than 3% among women aged 30–34, less than 2% among women aged 35–39 and less than 1% among women aged 40–44. The age of 30 seems to be a cutoff point at which 95% of women will end their single life and form their own family.

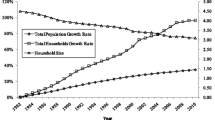

Second, from the perspective of marriage rate, it is clear that the pair of marriage and crude marriage rate have fluctuated between 1978 and 2018, as depicted in Fig. 2. The pair of marriage increased from 5.98 million in 1978 to 10.14 million in 2018, and the crude marriage rate increased from 6.2 per thousand in 1978 to about 8 per thousand in 2018. However, both of these two indicators show a continuous downward trend in recent years, which has attracted widespread attention from the society and academia. In the early years, the fluctuation of these two indicators might be related to the revisions of the Marriage Law. In 1980, for example, China, for the first time, amended its Marriage Law, which was first issued in 1950, and such amendment directly enhanced marriage rate in 1981. The second revision of Marriage Law in 2001 was also associated with an increased marriage rate. On May 28, 2020, the third session of the 13th National People's Congress voted to adopt the Civil Code of the PRC, and further observation is needed on the trend of marriage rate.

The interval between the first marriage and first birth has also narrowed. Zeng (1992) estimated that in the early 1980s, the age of first birth in China was 23–25 years old, and the interval between first marriage and first childbearing was 1.50–1.66 years. Since then such interval was shortened over time. It is perhaps that the postponement in the age at first marriage motivates people to have a child as soon as possible, or perhaps that premarital pregnancy has become common so that people have to get married (Yang 2015).

3.2 Family building and stabilization

The stage of family expansion begins with the arrival of the first birth, and ends with the birth of the last child, and the period from the birth of the last child to the departure of the first child from parental family is regarded as the stage of family stability. Since the founding of PRC, the age of first birth has largely delayed, the number of children substantially reduced, and the time span of the stage of family stability has been largely extended. The following attributes stand salient in this life stage of the family.

First, the average age of first child birth continues to rise, increased from 21.92 in 1950 to 24.64 in 2005, 26.61 in 2010, but slightly decreased to 26.55 in 2015 for women, a 5-year delay in 60 years (Liu and Zou 2011), as shown in Fig. 3. The postponement of the first marriage age also leads to the postponement of the first childbearing, which may reduce the fertility intention and even lead to childless in the life time (Yang 2015).

Data sources: Data of 1950-2005 come from Liu and Zou (2011); data of 2010 are from the sixth census, and data of 2015 are from the national one percent population survey

Average age of women at the first and second child and both interval between 1950 and 2015.

Second, the average number of surviving children of women shows a decreasing trend with the decrease of age as time moves forward (Fig. 4). What is most salient are two folded. First, women in 1982 and 1990 had more children than their peers in the later three time points, and second, regardless of age cohort, such pattern retains. However, even among women aged 50–54 who were strictly under the control of fertility policy, their average number of surviving children was almost 2 in 2010. Although women aged 35–39 have not yet gone through their reproductive years, their average number of children still exceeds 1.5. On the one hand, it shows that it is a common phenomenon to have children in China, and on the other hand, a large number of families still choose to have two or more children even under the strict fertility policy.

Third, the stage of expansion is characterized by an inverted-N shape, which first decreases, then increases, and then decreases again. In the 1950s, the average birth interval between the first and second children of Chinese women was about 3 years, but narrowed to 1.96 years in 1980 (Liu and Zou 2011). Since 1990, the average birth interval had been increasing, from 3.05 years in 1990 to 5.15 years in 2005, but down to 4.22 years in 2010. Although the average birth interval between the first and second child is not equivalent to the duration of family expansion – for example, there is no expansion stage for families without children or with only one child, and for families with three or more children, the average birth interval between the first and second children will underestimate the expansion stage—this indicator remains meaningful in the context of current China.

Lastly, related to the above point, the Chinese family shows a changing trend of shift from a long period of expansion but short time span of stability to a greatly shortened period of expansion but lengthened stage of stability. The research by Du (1990) shows that the expansion stage of Chinese families began to gradually shortened as early as the 1980s—the interval between women's first marriage and last birth decreased from 15.15 years in 1957 to 14.74 years in 1964, 9.02 years in 1977 and 6.24 years in 1981. Overall, the fertility rate has dropped dramatically over the past 70 years, with crude birth rate falling from 36.00 per thousand in 1949 to 12.43 per thousand in 2017, and the TFR from more than 6 children in 1949 to less than 3 children in 1978, around the replacement level in 1990 and 1.6 children today. Correspondingly, the time span of family expansion presents a conjoined U-shape to inverted U-shape curve. In the years of high fertility, a woman would have about 40-years to complete their reproduction if the birth interval between two children was 2–3 years. In this case she would be at least 55 years old once the youngest child grew up. Therefore, the expansion stage of the family was rather long in the 1950s, but it decreased overtime, while conversely, the time span of the stage of family stability has lengthened since children get married late and they tend to co-reside with parent prior to marriage.

3.3 Contraction and empty-nest

The family contraction begins with the marriage of the first child who will thereby form their own family. When all the children leave home, the family enters the empty-nest stage. Over the past 70 years, the duration of family contraction has been shortened and the duration of empty-nest has been largely prolonged. In extreme case, these two stages overlap with each other, and it has become common to see empty-nest among middle-aged people.

First, the interval of these two stages has largely shortened. Data from the former National Health and Family Planning Commission indicate that 45.6% of all families were in the stage of contraction or empty-nest in 2010. Indeed, these two stages totally overlap for single-child families. Even in families with two children, the interval between the two stages would be abut only 4–5 years on average.

Second, the starting point of empty-nest stage has been much advanced, from a much older age to the middle ages, and its length has been much prolonged. This mainly results from decrease number of children. Based on the average age of first marriage in post-1960-born urban residents (25 in women and 27 in men the maximum) and assuming that the interval between the first marriage and first birth is two years and that the only child generally leaves the natal family after the age of 18, the parents will enter the empty-nest from the age of 45–47, and thus, they will live in the "empty nest" for about 10 to 15 years longer than their parental generations. The three birth cohorts (1940s, 1950s and 1960s) entered the empty-nest at an average age of 57.5, 51.3 and 44.4 years old, respectively (Wu 2012). This suggests that people who formed their families after 1980 will enter the empty-nests 13 years’ earlier than their counterparts who formed their families in the 1960.

Corresponding to this, the proportion of empty-nests in the total family has increased. In 1982, it accounted for 12.64% of all elderly families (Yang and Wang 2019). Data from a sample survey conducted among those aged 60 or above, conducted by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in 1987, show that the proportion of empty-nest families was 16.3%. By 1999, such family accounted for 25.8% based on the data collected by the National Working Commission on Aging, whilst the data of China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey (CLASS) showed that the empty-nest rate of aged families has exceeded 50%.

Correspondingly, the proportion of elders living in empty-nest families has been on the rise. The 1990 census shows that a quarter of the elderly lived in empty nest. Report on the Development of Ageing Services in China shows that in 2013, nearly 50% of the elderly were empty nesters, with the total number exceeding 100 million. The only-child families enter the stage of empty-nest earlier, and they experience a much longer time span in empty nest. The two-child policy may significantly alleviate the aging status of urban and rural families (Zeng and Wang 2010).

However, some empty-nest families are only theoretical one rather than true empty-nest families, because their child(ren) might only be temporarily away from home, and some structural or emotional forces might drive their child(ren) who has previously moved out of the family to return to their parents' home, or the parents might move to live with their child(ren). In rural areas, parents might live next door to their child(ren). If this the case, such families should not be counted as a real empty-nest family, and the actual proportion of empty-nest families might be lower than the level presented in the data.

3.4 Family dissolution

The stage of family dissolution refers to the period from the death of one spouse to the death of the other spouse. Of course, family resolution may be a result of divorce, which is particularly so today due to the increasing rate of divorce. With the booming socioeconomic development and the consequent improvement of living standards and medical services, the life expectancy of Chinese people has continuously risen, while population ageing has become more severe, and the family has also become old.

This family dissolution is directly subject to the life expectancy—the longer people live, the slower the family will die. The life expectancy increased from 35 years before 1949 to 47 years in 1950, and rapidly increased to 67.9 years in 1981. By 2017, the Chinese tend to live a life of 77 years on average, 42 years increase in 70 year. It even extended to over 80 years in certain regions (e.g., Beijing and Shanghai) (Yang and Wang 2019). The extension of life expectancy has undoubtedly influenced the family forms and the family life cycle, particularly postponed the duration of family dissolution.

Correspondingly, the proportion of widowhood and the elderly living alone is relatively large, but the proportion of widowhood among elderly aged 60 years and over has a downward trend over time. In 1982, the proportion of widowhood was 43.61% among all people aged 60 and older, and 58.09% among women; in 2015, it reduced to 23.32%, a nearly 20-percentage points decrease in 35 years. A gender gap is also pronounced: it for male elderly decreased from 26.90% in 1982 to 14.05% in 2015, while decreased to 32.07% for female elderly (see Fig. 5). There are also rural and urban disparities in this regard (Wang 2013).

The duration of the stage of widowhood are increasing gradually. As Table 1 shows, the probability of male elderly aged 60 and over losing their spouse fluctuated little from 0.27 in 1982 to 0.26 in 1990, and then increased to 0.29 in 2015, while the probability of female elderly losing their spouse increased from 0.44 to 0.59.

Table 1 also shows that the average age of losing spouse of male elderly has increased from age 72.87 to age 80, and that of female elderly has increased from age 70.59 to age 76.3. The gap of average age losing spouse between men and women has increased over time. The cumulative duration of widowhood for a male elderly has increased from 2.46 to 2.87 years, while that of women has increased from 5.23 to 7.81 years. The duration of widowhood of women is 5 years longer than that of men.

In short, the characteristics of family life cycle has been closely correlated to macro context and embedded in structural and institutional forces. In the past 70 years, industrialization, urbanization and modernization have jointly reformulated traditional family life cycle, and the six-stage model of the family cycle has also been deeply reconstructed. Although the Chinese family is still resilient to outside changes, it has been deeply modified. The postponement of age at the first marriage and first birth means that the stages of family formation and family building have been largely delayed accordingly, which directly reduces the lifelong fertility rate of women, given that having children remains to be within marriage. This further makes overlap the stages of family expansion and stability, and the stages of contraction and empty nest period. These changes in turn bring about a series of domino effects on the family, simplifying family structure and weakening family function (e.g., childcare and old-age support), thus increasing the demand of social support from the family.

4 Conclusion and reflection

The family is the cornerstone of traditional Chinese society. A healthy family is able to fulfill the functions of the family that have not yet been externalized, and lay down a solid foundation for a stable, peaceful and sustainable society. If some families face problems, the society would have troubles; if many families have problems, the society may encounter instability and disaster.

The family is always under changes in China as well as in other settings. Scandinavian and Western European countries, for example, have the lowest marriage rate, highest divorce rate, widespread cohabitation; South and eastern European countries have extremely low fertility rate, smallest family size, and simplest family relationships. This new wave of change, termed as the Second Demographic Transition, has also spread to the east, including China, causing challenges to the family and force the family to adjust itself to adapt to the new situation.

Although Chinese families have not experienced such violent changes as those in western societies, family structure and family life cycle have all displayed similar patterns and characteristics to that of the west in recent decades. However, the fundamental difference between the family and other social institutions lies in that its members have an unbreakable blood bond; no matter where family members are, they are naturally connected by the blood ties, which make it extremely difficult for any external forces to break. This characteristic gives family resilience to withstand challenges, especially in China with a long history of family orientation and strong pro-family culture.

From the centennial perspective, it may be concluded that the life cycle of Chinese families have undergone great changes in the past century due to decreased family size and reshaped living arrangements, which can be collapsed into four stages, rather than traditional six stages. Changes in family life cycle are also interconnected with family forms, family relationships and family function. The share of large-sized families has fallen, while that of single-person families risen, which has turned traditional family into “network” family. Core family members (i.e., parents, children, and spouse) need not to live together under one roof anymore; the relationship among core family members becomes simpler, detached, or intimate but distanced. Meanwhile, market economy fosters a preference for individualized lifestyle, which has interrupted the balanced traditional family relationship, obstructed the successful implementation of family functions and lowered individual sense of family responsibilities. All of these changes not only reduce families’ ability to deal with societal risks alone, but also generate social risks.

From the decadal perspective, it may be concluded that, while facing great, radical, and profound social transitions, there is more continuity than change in the family. Chinese families are still marriage-based, and the majority of family has at least one child, which has sustained at least four stages of family life cycle by creating the stages of family building and family stability. Although many new family types have emerged, nuclear and stem families remain to be the most common family forms, and the number of generations in a family remains stable. This continuity of the family is in fact a choice of family strategy to cope with relatively low level of socioeconomic development, inadequate social welfare and public services, the negotiation and coordination between the government, society and family, and the inter-generational interactions and reciprocity.

Having acknowledged the continuity of the family, however, it is also important to pay attention to the reconfiguration of family life cycle. Since the empty-nests become much longer, it is necessary to introduce family-friendly policies in old-age support. Also, from the perspective of family development, providing childcare services for children younger than age 3 is urgent so as to alleviate young couples’ anxiety to have more than one child. To enhancing the capacity of family development, the government should make efforts to help the family maintain and strengthen its resilience, unity and cohesion in the new historical era. Only the family is good, the society can be stable and harmonious.

References

Benokraitis, N. (2014). Marriages and families: Changes, choices and constraints (8th ed., p. 16). Pearson /Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River.

Bradatan, C., & Kulcsar, L. (2008). Choosing between marriage and cohabitation: Women’s first union patterns in Hungary. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 39(4), 491.

Cherlin, A. (2017). Introduction to the special collection on separation, divorce, repartnering, and remarriage around the world. Demographic Research, 37(1), 1275–1296.

Du, P. (1990). A preliminary analysis of the urban and rural family life cycle in China. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 4, 24–28. (in Chinese).

Fang, F. (1987). The shifting patterns of marriage and family in last 30 years in China (1953–1982). Population & Economics, 2, 26–32. (in Chinese).

Glick, P. C. (1947). The family cycle. Marriage and Family Living, 9(3), 58.

Goode, W. J. (1963). World revolution and family patter NS. New York: Free Press of Glencoe.

Guo, Z., Liu, J., & Song, J. (2002). The current Family Planning Policy and family structure in the future. Chinese Journal of Population Science, 1, 1–11. (in Chinese).

Hirschman, C., & Minh, N. H. (2002). Tradition and change in Vietnamese family structure in the Red River Delta. Journal of Marriage and Family, 4, 1063–1079.

Liu, S., & Zou, M. (2011). Birth interval between first and second child and its policy implications. Population Research, 2, 83–93. (in Chinese).

McDonald, P. (1992). Convergence or compromise in historical family change. In E. Berquo & P. Xenos (Eds.), Family systems and cultural change (pp. 15–20). New York: Oxford University Press.

National Bureau of Statistics. (2015). National data. Available at https://data.stats.gov.cn/easyquery.htm?cn=C01. Accessed 20 Sept 2020.

Nicole, H., Liefbroer, A. C., & Poortman, A. R. (2015). Marriage and separation risks among german cohabiters: Differences between types of cohabiters. Population Studies, 69(2), 1–15.

Pesando, L., Castro, A. E., Andriano, L., Behrman, J. A., & Billari, F. (2018). Global family change: Persistent diversity with development. University of Pennsylvania Population Center Working Paper (PSC/PARC), 2018-14. https://repository.upenn.edu/psc_publications/14.

Raymo, J. M., Park, H., Xie, Y., & Yeung, W. J. J. (2015). Marriage and family in East Asia: Continuity and change. Annual Review of Sociology, 41(1), 1–10.

Reher, D. S. (1998). Family ties in Western Europe: Persistent contrasts. Population & Development Review, 24, 203–234.

Wang, S. (2004). The effects of population and family planning policy changes on intergenerational relations. Population & Economics, 4(9), 14. (in Chinese).

Wang, Y. (2013). An analysis of the changes in China's urban and rural family structures: Based on 2010 census data. Social Sciences in China, 12, 60–77+205–206 (in Chinese).

Wang, Y. (2015). A comparative analysis of the family structure in China’s different regions: Based on the 2010 census data. Population & Economics, 1, 34–48. (in Chinese).

Wang, Y. (2017). Social transformation and its influence on the contemporary family of China. Social Sciences in Chinese Higher Education Institutions, 5, 58–68+157 (in Chinese).

Wang, Y. (2020). Institutional change and household structure in contemporary urban China. Population Studies, 1, 54–69. (in Chinese).

Wu, F. (2012). Family life cycle structure: A theoretical framework and empirical analysis based on the CHNS. Academic Research, 9, 42–49. (in Chinese).

Yang, H. & Shi, R. (2019). The influence of youth's premarital cohabitation on the risk of their first marriage. Youth Studies, 5, 63–74+96 (in Chinese).

Yang, J. (2015). Has China really fallen into fertility crisis? Population Research, 6, 44–61. (in Chinese).

Yang, J., & He, Z. (2014). Continuity or change? Chinese family in transitional era. Population Studies, 38(02), 36–51. (in Chinese).

Yang, J. & Li, L. (2009). Intergenerational dynamics and family solidarity: A comparative study of mainland China, Japan, Korea and Taiwan. Sociological Studies, 3, 26–53+243 (in Chinese).

Yang, J., & Short, S. (2007). Marriage and residence pattern and fertility behavior in China. Population Studies, 2, 49–59. (in Chinese).

Yang, J. & Wang, S. (2019). Changes of Chinese families in the past 70 years. Chinese Social Sciences Today 5 (in Chinese).

Yu, J., & Xie, Y. (2017). Prevalence and social determinants of premarital cohabitation in China. Population Research, 2, 3–16. (in Chinese).

Yuan, H., Luo, J., & Zhang, S. (2016). The premarital cohabitation among youth women and marriage quality in China. China Youth Study, 9, 13–22. (in Chinese).

Zeng, Y. (1992). The method using census data to estimate the average marriage age and the first birth interval and its application in 2000 census data. Population & Economics, 3, 3–8. (in Chinese).

Zeng, Y. & Wang, Z. (2010). Projection and policy analysis on population and households aging in 21 century in Eastern, Middle and Western Regions of China. Population & Economics 2, 1–10+37 (in Chinese).

Funding

The study is jointly supported by National Social Science Fund of China (17ZDA122), the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (71673287), and China Women’s University (KY2020-0102).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The manuscript is not submitted to any other journal for simultaneous consideration. The submitted work is original and have not been published elsewhere in any form or language, unless the new work concerns an expansion of previous work. The corresponding author, and the order of authors are all correct at submission. The authors declare they have no conflicts of Interest/competing interests.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Cumulative probability of widowhood

Since the same person is independent to lose spouse at all ages and can only be widowed once, the cumulative probability of widowhood is the sum of the widowing probability at all ages for the elderly aged 60 and above.

1.2 Average age of widowhood

The average age of widowhood is actually the average age weighted by the probability distribution of husband's death under the condition of wife's survival, which represents the average age when the wife loses her husband.

1.3 Cumulative duration of widowhood

Since the same person is independent to lose spouse at all ages and can only be widowed once, the cumulative duration of widowhood is the sum of the widowing time that the elderly may experience at all ages.

W is the upper limit age in life table. \( l_{\left( x \right)}^{f}\), \(d_{\left( x \right)}^{f}\), \(e_{\left( x \right)}^{f}\) are statistics of the female’s life table. According to the same idea, we can get the cumulative probability of widowhood, average age of widowhood, cumulative duration of widowhood of male elderly population.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, J., Du, S. Family change in China: a-70 year perspective. China popul. dev. stud. 4, 344–361 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-020-00068-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42379-020-00068-0