Abstract

Nature-based learning is increasingly being implemented and explored within early childhood education settings. Thus, including sustainability, environmental education, place-based education, and other similar topics may help prepare future educators and teachers to provide meaningful experiences for children in the outdoor environment. The purpose of this study was to document the student experiences of a newly developed practicum course offered at Bow Valley College in Calgary, Alberta, for early childhood education and development students. The practicum is focused on nature-based learning and outdoor play. To gain a more profound understanding of the experiences of the college learners participating in this course, a qualitative study was designed using phenomenology and case study approaches. Data were analyzed by looking for significant statements that describe the meaning of the course experience for each participant, taken from their final assignment, as well as instructor reflections. Findings confirm the importance of providing a diversity of embodied, outdoor learning experiences for college students, as well as opportunities for reflection. The important role of partnerships, relationships and communication is also highlighted with this study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Practicum courses provide an invaluable experience for pre-service teachers and early childhood educators. They gain the opportunity to apply their knowledge of child development and curriculum planning, as well as experience a classroom setting to gain practical skills with children (Kim, 2020). Practicum experiences are indeed core to many teacher education programs and early childhood education programs around the world since, among other benefits, they play “a key role in bridging the gap between theory and practice” (Hamaidi et al., 2014, p. 192). Bow Valley College, located in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, offers a two-year diploma program in early childhood education comprising four mandatory practicum courses with placements in early childhood education settings.

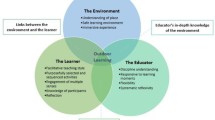

In 2020, the curriculum for the third practicum in the diploma program was re-developed to focus on nature, and outdoor and environmental education, to better align with new developments in the field of early childhood education and development. The new practicum course aims to transform college student perceptions of outdoor pedagogy, inspire them to see possibilities for outdoor play and learning for young children, and to connect theory with practical experiences in a nature-based setting. Providing pre-service early childhood educators with mandatory practical training on outdoor and nature-based early learning [NBEL] opportunities is a new, innovative, and theory-grounded approach that aims to better prepare educators for a growing demand in NBEL (North American Association for Environmental Education, 2023). Research and documentation of this practice may help guide pre-service training for early childhood educators in Canada and internationally.

Though there have been studies examining various aspects of pre-service teachers or early childhood educators’ practicum experiences (e.g., Hamaidi et al., 2014; Kim, 2020; La Paro et al., 2018), there has been little attention to outdoor and nature-based practicum experiences. The purpose of this study was to better understand college student experiences of the course, such as meaningful learning experiences with children, course topics that particularly stood out to the college students, transformative dialogues and readings, and formative assignments that were most useful. To this end, we utilized a phenomenological approach, given its potential to offer insight into “particular experiences and the meanings that participants draw from them as they engage with the world” (Telford, 2020, p. 48). Within this article, we describe findings from a study conducted in the summer of 2021. It is our hope that these might inform initial early childhood teacher development practices across Canada and beyond.

Outdoor pedagogy

Outdoor play and learning are crucial for children’s wellbeing and development. The outdoors offers children a chance to move around, explore, have rich sensory experiences, and engage in social interaction with adults and peers. As Smith (2020) writes, “on-the-land learning gives us the opportunity to understand Nature, and through that, ourselves and our interconnected cultures” (p. 7). Further, active outdoor play is recommended in order to promote children’s healthy development (Tremblay et al., 2015). Authors Loebach and Cox (2020) describe how learning through play is enriched in outdoor contexts:

Play and language tends to be more complex, more dramatic play is observed, and children engage in more physically active play … Outdoor environments which also include substantial nature elements and materials can offer even more play opportunities; nature based play spaces have been shown to foster more varied and complex play than traditional outdoor playgrounds. (p. 1)

In the field of early childhood education, the outdoors is increasingly being viewed as a place of learning rather than as a place for children to expend energy. Outdoor pedagogy is an educational approach that applies these principles. It is a pedagogy rooted in the land and local ecology, and that is in line with recent research attending to child-nature relations (Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles et al., 2018), multispecies relations (Pacini-Ketchabaw et al., 2016), weather experiences (Rooney, 2018) and the benefits of children spending time learning and playing outdoors (Chawla, 2015). As noted by Deschamps et al. (2022), “the outdoors provides a calmer, warmer, and more cooperative learning context that facilitates interactions between students and teachers and improves students’ attention, engagement, self-discipline, enjoyment, and positive behaviors” (p. 2).

Attending to Indigenous worldviews and knowledge of the land is an important consideration in outdoor pedagogy. In Canada and elsewhere, outdoor educational programming takes place on land that may be traditional lands for one or more Indigenous groups. In the spirit of respect and reconciliation, it is important for educators to attend to local knowledge that Indigenous partners can offer. Increasingly, it is suggested that researchers and practitioners take a critical look at the settler colonialist perspective that has driven the field of education for decades, and decolonize practices in education (Calderon, 2014; George, 2019), and early childhood specifically (Harwood et al., 2020; MacEachren, 2018; Nxumalo, 2019). Notably, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants by Kimmerer (2013) has become very popular with the outdoor pedagogy movement in North America, providing guidance on how to blend Western scientific knowledge with Indigenous perspectives. Sustainability principles can also be communicated through NBEL (Boileau et al., 2021), who conducted a survey study of NBEL in Canada, found that nature-based early learning programs in Canada could help address several of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development goals and promote key competencies that children will need to address issues of sustainability (e.g., self-awareness, anticipatory, collaboration, systems thinking, and integrated problem-solving).

Although implementing an outdoor pedagogical approach may come naturally to some educators and teachers through their personal interest, pre-service educators require “support and guidance to fully comprehend the significant potential for learning provided in outdoor learning spaces” (Wishart & Rouse, 2019, p. 2288). Wolf et al. (2022) recently conducted a literature review of the research on outdoor teaching in initial teacher training from early childhood to secondary education and found that many teachers report low self-confidence in delivering outdoor education and that pre-service teachers “feel unable or are unwilling to teach outdoors, due to inadequate education or training” (p. 200). Thus, it seems important to provide meaningful learning experiences for early childhood education college students to ensure they are competent in delivering outdoor education to young children.

Experiential learning in early childhood teacher education

When knowledge is put into practice, college students gain direct experience that can help solidify their understanding of a certain topic. As Dumont et al. (2012) indicate, “many scholars agree that the ultimate goal of learning and associated teaching in different subjects is to acquire adaptive expertise, i.e., the ability to apply meaningfully-learned knowledge and skills flexibly and creatively in different situations” (p. 3). Within the context of outdoor pedagogy, this adaptive expertise is particularly necessary when interacting with children in outdoor environments, a situation that inherently requires flexibility and adaptability to changing situations (e.g., the weather, children’s mood, interests, and energy). Training that involves practical experiences with children, opportunities for reflection, and increased comfort and skills outdoors can help college students gain confidence and skills in this type of pedagogical approach.

As play is a key component of early childhood education, providing early childhood teachers with practice and experience of play during their formative training can lead to a richer understanding of the importance of play for children and how to facilitate outdoor play. Adamson et al. (2020) conducted a study on play workshops and found that “experiential learning about play is important because it provides an opportunity to reconnect with their previous experiences of play thus enabling a connection between their previous beliefs and practices with their emerging understandings of play as pedagogy” (p. 265). The authors note that when early childhood education college students are from countries where more didactic approaches are applied with young children, it can be particularly important to offer them not only alternative theoretical perspectives but experiential learning and support for transformational learning (Adamson et al., 2020). A playful approach within experiential education can also yield positive outcomes such as enhanced creativity, humour, motivation, and positive emotions (Leather et al., 2021).

A study conducted by Wishart and Rouse (2019) with three practicing early childhood educators confirmed the importance of providing educators with professional development with regards to the use of outdoor learning spaces and natural materials. The professional development that was offered to these educators was directly related to their workplace and helped change the educators’ perceptions of teaching in their outdoor space. Notably, the authors found that “the process of perception change documented in this study suggests some early childhood educators need time, space and immersive experience coupled with extended, focused PL [Professional Learning] … to modify understandings, appraise values and redefine their role in effective provision of outdoor play experiences” (Wishart & Rouse, 2019, p. 2295).

Practicum experiences are crucial to becoming a skilled early childhood educator or teacher and are one of the most important experiences in teacher education programs (La Paro et al., 2018). These experiences look different based on the program, country, and available local resources, such as settings where college students can be placed and the availability of mentor teachers. The central component, however, is described by La Paro et al. (2018) as “a system which involves a teacher candidate and cooperating teacher in the classroom within a relationship that includes multiple elements with the intended outcome of developing effective teaching practices” (p. 366). In quality field placements, college students observe skilled teachers and children in action, apply knowledge gained through classes, and develop professional skills (Linn & Jacobs, 2015). In fact, field placements can be transformational for college students. Linn and Jacobs (2015) found that teacher candidates’ practicum experiences were very personal and could help college students link together their own professional goals, belief systems, real-world experiences and conceptual understanding.

Thus, the literature points to the importance of guiding early childhood educators in their learning of outdoor play and learning experientially and through field experiences and placements involving children and skilled educators to observe. Guided by these concepts, a new practicum course was imagined for Bow Valley College students in the Early Childhood Education and Development Diploma program. This practicum would focus on nature, outdoor play and learning, and sustainability, and would be a mandatory course.

Developing the new practicum course

When first tasked with writing the outdoor practicum course, I [Linda] entered into the work with some trepidation, but also excitement, as the program was leaping into the world of outdoor pedagogy. How could I create a course that offered children, families, college students, early childhood education and development [ECED] settings, as well as instructors, opportunities to engage in diverse outdoor experiences that could perhaps shift ideas and thinking about outdoor play and learning? I was inspired by the local Indigenous teachings, the “Blackfoot ways of knowing” (Bastien, 2004), as well as outdoor pedagogical practices.

I created a course that employs embodied experiences. college students engage in practicum seminars outside the confines of a traditional indoor classroom space. The instructor and college students meet outdoors, near the college campus. Course theory is woven into full-body experiences where college students explore spaces and places on their own and with others. At their practicum settings, each experience offered by the pre-service teachers to the children is required to be outdoors, preferably beyond the fence of the playground space, inspired by Pitsikali and Parnell (2020), who write:

Fences of childhood, which are signifiers of security, have acquired interesting meanings… children of the global north appear to live in an “archipelago of normalized enclosures.” Scholars have often criticized the capacity of playgrounds to support children’s participation in public life and space. (p. 657).

To avoid the confinement of playground space and to encourage venturing into naturalized spaces and places, the curriculum content offers suggestions to the college students and their mentors to seek out new areas near the ECED practicum setting for children to explore and discover.

Land-based knowing, Indigenous perspectives, and cultural diversity are strongly represented throughout the practicum course. I was fortunate to work alongside a Knowledge Keeper and curriculum specialist as I wrote the curriculum. A Knowledge Keeper is a term utilized to describe a person who holds traditional knowledge and teachings. The Elders provide the Knowledge Keeper with guidelines on caring for the knowledge given to them (Queen’s University, 2023). I sought advice from the Knowledge Keeper in embedding Blackfoot teachings within the course. Many students within the college are unfamiliar with the local Indigenous culture. College students are also encouraged to share their backgrounds and family experiences in regard to the outdoors to open conversations, to be culturally inclusive, and to ground the theory we study.

The goal of this practicum is to create a shared and individualized learning situation for college students in which they could then offer children meaningful provocations and invitations in outdoor spaces. A critical component of the course is to achieve the common understanding that outdoor learning experiences must be an important consideration in every early childhood setting and that outdoor pedagogy requires intentionality. To deepen the understanding that outdoor play and learning requires careful planning, college students in the practicum course are introduced to theoretical concepts regarding the pedagogy of outdoor nature play. The textbook selected to guide this course is Outdoor and Nature Play in Early Childhood Education (Dietze & Kashin, 2019), a college student-oriented book that covers topics such as programming from a four-season perspective and the relationship of outdoor and nature play to children’s development, health, and thinking. Given that this new practicum had been delivered twice already (September to December 2020 and January to April 2021), it seemed appropriate to conduct a study to examine the transformations that had been anecdotally observed.

Methodology

This study sought to address the following questions: (1) How do early childhood education students experience a practicum course focused on nature-based learning and outdoor play? (2) In what ways did the course structure, materials, readings, and setting promote meaningful learning of outdoor pedagogy? To best explore these questions, we conducted a qualitative study with one particular class of college students enrolled in the outdoor practicum course over one semester (May to August).

Phenomenology is being increasingly used in educational research (Stolz, 2020), including environmental education research (Nazir, 2016). It is the study of a phenomenon that can be explored “with a group of individuals [emphasis removed] who have all experienced the phenomenon” (Creswell, 2013, p. 78). Others have found it is useful when investigating college student experiences in higher education (Webb & Welsh, 2019), pre-service environmental education training for teachers (Campigotto & Barrett, 2017), and professional learning on outdoor pedagogy for early childhood educators (Wishart & Rouse, 2019). In this case, phenomenology was chosen to examine the college student experience of completing the outdoor practicum course in the summer of 2021. We sought to generate knowledge of the lived experience of college students to inform teaching practices. Given that the context was also a “bounded system [emphasis removed], bounded by time and place” (Creswell, 2013, p. 97) in the form of one particular group of college students enrolled in the course in one specific semester, the study was also considered through a case study lens. This allowed for multiple points of data to be included, which can help validate research findings. We considered the “case” to be the entire class, including intructors.

Research context

We co-taught this practicum course in the spring and summer months of 2021 over one 15 week term. In the first half, Linda led online seminars once a week for the class and the college students were placed in various child care settings where they were to complete two full days of practicum experiences weekly. All activities led by the college students were to be outdoors, thus supportive childcare centers were sought along with on-site mentors to assist the college students in developing skills. In the second half of the course, Elizabeth led the online seminar portion of the course online once per week and the practicum days were either class or individual outdoor experiences also led by Elizabeth. This format delivery was unique to that particular semester, given that many preschool programs (hence practicum opportunities) closed for the summer at the end of June. A portion of the practicum was therefore focused on practical outdoors skills that would increase educator interest and confidence in being outdoors through lived experiences (see Table 1).

Note: Seminar was delivered online due to COVID-19 safety restrictions; the class was able to meet outdoors, physically distanced as of July with the easing of restrictions.

The delivery of this course was in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact cannot be ignored. As was noted in a global survey, the “pandemic has negatively impacted the social and quality of life of post-secondary students and staff globally” (Nowrouzi-Kia et al., 2022, p. 8). In our case, planning for the delivery of the course presented challenges such as constantly changing restrictions and regulations on the numbers of people allowed for indoor and outdoor gatherings, limited access to the college building, college students needing to isolate at home or being sick, and finding practicum placements for them for May and June. College students were placed in practicum settings that were willing to host despite the pandemic; however, the instructor was only permitted to visit these settings virtually.

The weekly seminar portion of the course would normally have been delivered in person, but meeting in person was prohibited, thus the course shifted to an online platform for these sessions for the semester. Linda particularly found the separation of time, space and shared experiences limited her ability to grasp how the theory was being synthesized. Elizabeth, on the other hand, was able to share outdoor experiences with the group, and though some college students were apprehensive at first, she noticed they were relieved to finally have some contact with their peers and with their instructor after so much online learning since the beginning of the pandemic over a year before this course.

We, as early childhood education instructors, are not alone in having experienced challenges teaching during the pandemic. van Groll and Kummen (2021) note that “COVID-19 created conditions for learning that were unprecedented in [their] teaching lifetimes” (p. 31) and required early childhood education instructors to “think imaginatively to create supportive pedagogical spaces for future early childhood educators” (p. 31). Many post-secondary institutions around the world pivoted to online platforms during the pandemic. Kim (2020) shared that they, too, pivoted due to COVID-19 and redesigned a practicum course for early childhood education students. Doreleyers and Knighton (2020) wrote that although transitioning to online learning provided an opportunity for learners to continue their coursework, this posed a challenge for college students who may not have been used to this format, a challenge that was exacerbated by the ongoing stress of coping with the COVID-19 pandemic. Though our focus with this article is not on the effects of the pandemic, the fact that this study was conducted during this time is important in providing context. We felt fortunate that the outdoor focus of the course aligned with practicum goals and that, by July, groups were permitted to gather outside, thus allowing for a portion of group learning.

Methods

To best answer our research questions about college student experiences of the practicum course, the ways in which the course structure, materials, readings, and settings may have promoted meaningful learning of outdoor pedagogy, we looked at several data points. Our primary source was the course’s final assignment, due on the last day of the course. The assignment is entitled “Reflective Pedagogical Documentation.” The college students are asked to reflect, document, and ultimately share their learning journey in a PowerPoint presentation (or similar software). The presentation consisted of 10 slides, each with a concept or theme related to the course content and experiences (these can vary somewhat as instructors may want to pick the significant topics during their term). In the summer 2021 term, the ten topics for the assignment are shown in Table 2.

The college students were encouraged to include visuals and learning artifacts (e.g., photos, quotes by children, drawings, audio clips) within each slide and to tell their own story, thus also providing an opportunity to practice documentation skills that they would apply in their profession, to show children’s learning. Having these reflections as data allowed us to “draw on the knowledge and understanding that individuals bring to an experience” (Telford, 2020, p. 52) and to examine the meaningful learning gained from the course as described by the students themselves. Of course, we acknowledge that drawing data from college student assignments can be problematic, since they may enhance their reflections to gain a higher grade or may not put in effort into meaningfully reflecting on each theme. Yet, this seemed like an effective way to obtain learner perspectives without asking them to do extra work, such as participate in focus groups or surveys, at a time when learners generally were struggling with pandemic-related personal challenges.

Additionally, both instructors observed the class, paying attention to reactions, comments, and behaviours, as well as the college students’ interests, during their time teaching the class. Elizabeth took photographs when she met with the class for outdoor practicum days, to document the learning activities. These were shared with Linda and discussed throughout the analysis process. Finally, written reflections were produced by each researcher, individually, following their experience teaching half of the course. Given that Elizabeth was meeting physically with the college students, her five page reflection and description of each week provided an opportunity to validate some of the findings.

Researcher positioning

It is common practice in phenomenological research to suspend the researchers’ natural attitudes, beliefs, assumptions, and opinions - referred to as bracketing - in an attempt to prevent these beliefs and attitudes from distorting findings (Stolz, 2020). The role of bracketing is contested, but one of the keys to gaining rich understanding of an experience is “through the adoption of a non-theoretical and unprejudiced standpoint leading to the creation of a relationship of deep understanding, empathy and indwelling with research participants” (Telford, 2020, p. 53). Our role as instructors as well as researchers, is referred to as “insider research” by Bulk and Collins (2023). The authors write, “We argue that insiderness is more than sharing characteristics: it is a situated, fluctuating, and ‘felt’ experience. The complexities, judgments, and emotional labor associated with insider research can challenge researchers in potentially very personal and unexpected ways” (p. 1). The insiderness we experienced as researchers both created an opportunity to gain direct insight into the course experience and the potential for influencing our findings due to our biases and intended outcomes of the course. We intentionally did not apply a strict bracketing process, and were rather inspired by more recent phenomenological approaches, where the researcher may reflect on their experience and how it may be influencing the research process (Nazir, 2016). Understanding that it was impossible for us to remove ourselves from the research, we instead made our identities as researchers and instructors part of the research process.

Participants and ethical approval

At the beginning of the term, the study was presented to the class of 17 college students who were also pre-service early childhood educators (henceforth referred to as college students or pre-service educators), and they were invited to ask any questions or bring up any concerns to a contact within the department, to avoid discomfort in bringing up concerns to their current instructors. The class was naturalistically observed throughout the term (as part of our role as instructors) and in the last weeks of class we invited college students to contribute their final assignment as part of the study. A consent form was sent digitally and responses tracked by a department administrator. Hard copies were also provided during the last class, at which time the instructors walked away from the group, allowing them time to decide in private. Signed consent forms were placed in an envelope that was then sealed by a college student before the instructors returned to the group. To meet ethical requirements, assignments were graded, and final course grades were posted before either researcher knew which college students had consented to participate in the study. Written consent to analyze their final assignment was granted by 15 pre-service educators, thus two assignments were not included as data. The study was approved by the Bow Valley College Research Ethics Board.

Analysis

In order to locate significant statements (Creswell, 2013) in the college student assignments, we both carefully re-read the final assignments and independently listed sentences or phrases that seemed significant. We specifically looked for sentences that seemed to allude to college students’ personal growth and learning, changes in their attitudes, and meaningful events from the course, rather than descriptive writing and direct references to course materials. We focused on the last slide of college students’ “personal top moments” of the course, as this was not driven by a particular theme. Linda identified 19 statements pertaining to a growth in understanding of outdoor pedagogy and 13 that alluded to meaningful learning experiences, Elizabeth identified 39 and 47, respectively. For each passage we wrote a brief interpretation or summary. We then compared our findings and discussed the 18 passages that we had both highlighted, and again wrote a brief interpretation that served as a code. These codes were combined and grouped in various ways, until six themes emerged that we agreed represented the findings.

Findings

Six main themes emerged from analysis of the data that highlight the meaningful aspects of the course experienced by the college students: (1) Embracing and preparing for the weather; (2) Learning from and with children; (3) Deepening a personal connection to nature and the Land; (4) Group discussions and building relationships; (5) Diversity of perspectives; (6) Increased understanding of the educator’s role. In this section, we describe and interpret each theme, and provide examples of significant statements from the college students.

Embracing and preparing for the weather

While teaching this course, we discovered a variety of attitudes, experiences and responses to weather based on each college students’ personal life story or narrative. Many college students in the program were raised outside of Canada in warmer climates, so the idea of outdoor play during inclement weather is new, as demonstrated by this quote:

Being a new immigrant to Canada, I used to think that children will not like being outside in the cold, or that they will get sick from being outside in the cold fresh air. However, this practicum helped me to understand how playing outside in all weather present their own unique opportunities for exploration and learning, and child’s overall development.

The approach of preparing for all weather conditions was discussed and practiced over the duration of the practicum. Sometimes the college students had concerns about upcoming weather such as rain, only to find that it was not an issue. Our goal was to support college students in becoming part of the weathering world (Rooney, 2018) and to learn to be flexible and adaptable, as weather can teach us (Smith, 2020). This pre-service educator reflects on what she learned about preparing for the weather after her field experience placed in an outdoor program:

I am grateful that I got to experience an outdoor practicum site and see the challenges and preparations that occur during severely rainy and hot weather. If you have the required layers and gear needed for all types of weather, you are always comfortable.

This quote demonstrates the growth and learning that can come from experiencing a practicum placement in an outdoor program. We found that the combination of discussing with peers and instructors, reading from the textbook, experiencing weather for themselves, and reflecting on their own values was helpful to support the college students’ learning. In the case of this class, given the international background of many of the college students, additional support was warranted, and their own fears needed to be addressed in a respectful manner in order to help them develop confidence being outdoors.

Learning from and with children

The college students often reflected on the value of learning about outdoor nature-based learning along with children. In having to lead and deliver outdoor child-centered experiences while placed in a childcare center for six weeks, the college students saw the children’s reactions to their provocations, which provided valuable feedback. In some cases, the outdoor experiences did not go as planned, for example if it started raining, and the college students had to quickly adapt. The following quotes from two of the student assignments demonstrate the importance of experiencing outdoor play and learning along with children:

I found that children were more involved in exploring materials and making their own play rather than in the way I planned and directed to them.

I feel I have developed a deeper understanding of outdoor pedagogy and play throughout this semester, being able to implement activities outdoors to see what interests children while also allowing them the freedom of child led play.

Through learning directly from their experiences with the children, the college students gained understanding of children’s needs and interests in an outdoor environment. Inquiry-led learning is central to nature-based educational approaches (Anderson et al., 2017; Merrick, 2019), therefore allowing pre-service educators to learn along with children was imperative. Though we were unable to place everyone in nature-based programs such as forest schools, in the second half of the course, the college students were able to compare their experience to those of their peers which provided insight into different approaches. As one pre-service educator noticed, the children’s behaviours provided key learning:

Even the play environment had a profound effect on how the children used the provocations. I observed that when I set the provocations outdoors, the children are more engaged, cheerful and creative in their learning activities.

Through intentional outdoor provocations, the college students discovered a change in how the children interact with one another within the outdoor environment. This echoes what Wolf et al. (2022) suggest, that outdoor learning is more relevant when pre-service teachers can observe the ways in which children learn outdoors.

Deepening a personal connection to nature and the land

With the college students having the opportunity to experience the outdoor environment directly through facilitated learning activities and without the pressure of a group of children to lead and care for, an opening was created for them to reflect on their own values and spend time, both with classmates and alone, immersed in a variety of natural environments. The college students took to this format quickly and became increasingly comfortable as weeks went on in the second part of the course. Figure 1 shows the class exploring the Bow River, in an area where none had been before, just a short walk from the college.

The two following quotes provide examples of how much the college students gained from having the opportunity and motivation to walk around local parks and natural spaces:

To the places I visited throughout practicum I can say I built many connections to the land(s). I learned and discovered my surroundings, the beauty of nature within itself and history beyond that.

Like a child, I was so excited with all the new, interesting and picturesque surrounding. It was a very sensorial experience. Feeling the wind, the different smells wafting from all directions, the different sounds around me – birds chirping, people talking, the crunch of stones under our feet and the peaceful sound of rushing water as I walked near the shore of the Bow River.

These quotes from the pre-service educators gave us a glimpse into how learning outdoors provides a different educational experience. Gray and Colucci-Gray (2018), who explored developing ecological awareness in undergraduate student teachers, refer to “enactivism” (p. 343), which involves the body, mind, and environment interconnection. When individuals are within a place, making connections to that space and place with their mind and body, they are “coming to know” (p. 344) about themselves and their environment, which was also observed in our study.

Additionally, the Thursday individual nature experiences also seemed quite meaningful for some college students. For example, one wrote the following:

My most favorite individual learning is the Week 13 Sit Spot Reflection. It is not often that I get to sit and reflect. Doing that Week 13 activity gave me a new perspective on the importance of sitting down and looking at things in a deeper way. I was able to see and thought of how the sky connects me with my family back home in India.

Slowing down and pausing is imperative to aid college students connection to the outdoors, referred to as a slow pedagogy (Clarke, 2023). Researchers Payne and Wattchow (2009) point out, “A slow pedagogy, or ecopedagogy, allows us to pause or dwell in spaces for more than a fleeting moment and, therefore, encourages us to attach and receive meaning from that place” (p. 16). Through the act of slowing down, we allowed space for this college student to be able to connect back to her family and her personal experience, enriching the moment of the sit spot.

Educators need to have a positive personal connection to nature if they are to bring children outside, to embrace all weather, and to think creatively about how to lead play and learning in an ever-changing environment. It appears that this group of college students appreciated the opportunity to meaningfully engage with the land and gain an understanding of the local environs. Building up college students’ appreciation for nature could be a first step in preparing them to include outdoor pedagogy in their later practice as educators.

Group discussions and building relationships

In the first half of the course, the college students and I, Linda, only met together online in weekly seminar class. To facilitate relationship building online is more challenging; however, by placing college students in smaller groups each week, I noticed that they were still able to make connections with one another. As this college student notes, the online format provided some initial comfort and security, as “even though it is online, seminar discussion is a big help for me because I feel scared or rather shy talking in front of other people” (quote from pre-service educator).

While the online teaching format offered the college students and instructor the ability to collaborate safely from home; learning about outdoor pedagogy indoors is counter-intuitive. In the second part of the course, the college students discovered that meeting in person offered them so much more in terms of relationships and playful collaboration. As Elizabeth wrote in her journal after the third week of outdoor class, “we started by going around the circle and sharing how everyone was feeling and how confident they were in taking children outdoors. Already, the students are sharing that their confidence has increased over the last couple of weeks.” Having this space to share as a group was key. It allowed me, Elizabeth, to meet the college students where they were at, and for them to feel heard. One college student wrote about her experience with her classmates:

We also worked together to assess different parks for risks and hazards and working together allowed us to each share things that we may not have otherwise thought of. I also enjoyed building a chair with some classmates from natural materials and winning as a team because we worked together and put our ideas together in making a durable chair out of nature’s gifts.

Participating in learning activities as a group, such as filling out a risk assessment sheet for a park or making a chair out of natural materials, allowed the college students to experience the growth of their own relationships while engaging with the outdoor environment. In Fig. 2, college students are seen playing in the water as part of a role-playing exercise where some were pretending to play, and others were practicing educator’s skills like observation and note-taking.

Community building is arguably and important factor to consider withing post-secondary teaching approaches. When students have the opportunity to be playful, as in the above photograph, and share in the silliness of getting wet and pretending to be children, they can learn alongside each other. In a similar vein, the following quote demonstrates how friendships can be created through learning in a community:

Doing the provocations and activities with my classmates also allowed me to build friendships with people in the same field. It was nice to share our ideas and have like-minded people to talk to.

Playful experiences outdoors created space for connecting with others, which echoes Dietze and Kashin (2024), “Through play, adults learn many valuable skills, including relationship skills, communication, innovation, problem solving, and visualization” (p. 59). Through offering opportunities for the group to be playful, whether online or in person, students were engaged in a learning community where they built relationships and communicated with peers.

Diversity of perspectives

Providing a diversity of perspectives is important in early childhood teacher education. Not only did this particular class have two instructors, but several guest presenters were invited to share with the class. These included one online presentation and three presenters during the outdoor practicum days led by Elizabeth. For example, Fig. 3 shows the class listening to a presenter discuss her outdoor program for families.

This allowed students to hear from practitioners and to hear of the various ways that outdoor educational experiences can be implemented for young children. Several students highlighted the presenters and diversity of perspectives in their reflection assignment.

Further, as part of the course curriculum, multiple connections were made to Indigenous knowledge and practices. We agree with Lees et al. (2021) that this is key to dismantling settler colonial narratives that largely guide the field of early childhood education. Thus, to support a stronger connection to the land and to further acquaint the college students to the local Indigenous teachings, specific information was shared within the course from Indigenous writers and individual learning activities were also assigned to the students. As noted by one college student, an activity based around the medicine wheel was a meaningful aspect of the course:

The medicine wheel was one of the activities that helped me better understand the different aspects of my personality. I think that this will be my responsibility to teach children about the importance of the medicine wheel at early age. As stated, this will help them to remain balanced at the center of the wheel while developing equally the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects of one’s personality.

College students also heard directly from an Elder who came to share his water teachings with the class during one of the outdoor practicum days. When the Elder spoke to the college students, his blessing in Blackfoot transcended understanding. Both of us observed the students to be very attentive and interested. As he continued to speak, fluctuating between English and Blackfoot, his style of speech coincided with a process of connecting with the world, land, and water, supporting the college students to think about their own cultures and how they connect to his teachings. One pre-service educator reflected that the Indigenous content had been meaningful to her:

I have always had a personal connection to nature and the land it grows on. As I learned more about the Indigenous culture, beliefs and values throughout my courses, I noticed a correlation to my own beliefs and practices towards land and Mother Earth. Learning about Indigenous knowledges gave deeper meaning to the values and beliefs I had started to develop.

Having a variety of perspectives and an emphasis on Indigenous worldviews shared throughout the course seems to have enriched the college student’s learning experience about outdoor pedagogy. It is not surprising that the college students reported that this was important to their learning. As instructors we hoped our class would remember that the land and nature cannot be separate from humans and for them to value their own ecological identities as educators (Gray & Colucci-Gray, 2018).

Increased understanding of the educator’s role

In addition to the above themes, the students seem to connect outdoor pedagogy to their role as future educators. We found this to be an unexpected theme as it was less focused on content from the course than the others. One student wrote:

I fully understand the benefits of outdoor play to children. I saw how authentic the play was. I witnessed the pure joy and the child-initiated play. This experience was so rich that it inspired me to offer more play-based, child-led experience, step back, and be amazed to witness a mighty learner and citizen emerge in a child. This experience also re-emphasized my role as a role model and supporting the children’s right to play outdoors.

Woven into the comment from the student is the view of the “mighty learner and citizen” (Makovichuk et al., 2014, p. 39) which is a key component from the Alberta Early Learning and Care Framework. The quote speaks to a sense of responsibility that early childhood educators have in providing opportunities for children’s outdoor play and learning. There is an understanding that what outdoor environments provide is different than anything an indoor early childhood environment can provide. As Dietze and Kashin (2016) wrote, “children’s curiosity and learning is triggered in spaces and places where unique materials and resources are available, and are influenced by adults that support their sense of wonderment” (p. 1). College students in this study seem to have gained an understanding that this is part of their job as educators. Another college student quote echoes this:

I conclude that after I learned the benefits of outdoor play, I am willing to take a risk and promote outdoor play in my personal and professional practice. Our job as educators is to make sure that children are safe, but safety should not mean the absence of risks. When an adults show positive attitudes about outdoor the children would adopt the desire to be more outdoor in any type of weather.

In addition to content knowledge of outdoor pedagogy and increased skills in delivering outdoor, nature-based early learning, students in this course appear to have additionally learned of their important role in facilitating children’s outdoor play and learning.

Discussion

In this section, we discuss the findings of our study in a broader context, including possible implications for other post-secondary instructors in the field of early childhood education. Primarily, we believe that a few key approaches can guide effective delivery of outdoor and nature-based early childhood practicum experiences or applied courses: (1) Relationships and local collaborations, (2) Reflective practice, and (3) Ongoing communication about the learning format.

First, we echo one of the main themes found in Wolf et al.’s (2022) research on outdoor education in initial teacher training from early childhood to secondary education, which was collaboration and partnerships. When it comes to finding suitable sites for pre-service teachers and educators to experience a nature-based pedagogical approach, relationships with local providers are key. Such programs are often smaller and private (at least in Canada) and networking on the part of instructors is important in order to be able to place students in quality programs with teacher mentors that demonstrate a commitment to outdoor play and learning. Further, as Wolf et al. (2022) note, collaboration or partnerships with the local community – for example botanical gardens, schools, or community members – can enhance place-based education. These authors note that “when PSTs [pre-service teachers] explore place-responsive education they learn how to utilize local people and places in their teaching” (p. 207). In our experience, local collaborations can help create a richer experience. Relationships pre-service educators develop with each other, with instructors, with teacher mentors, and with children are central to any practicum experience, and in the case of an outdoor practicum, relationship with the land can be added to this list.

Second, reflection is a crucial part of student learning and particularly teacher training given that educators will need to be skilled at reflecting on children’s learning and their own pedagogical approach (Foong et al., 2018). Thus, having the space and time to reflect, both individually and collectively, through experiences facilitated by the instructors can ensure that the practicum experience is meaningful. College students can examine new experiences, fears, concerns, excitement through the lens of their own experience and potentially develop an increased sense of safety and comfort in a natural environment. Including reflective course assignments along with field-based experiences can help pre-service teachers to process their experiences. This type of reflection is “an important tool that promotes thinking about new knowledge they [the pre-service educators] are gaining from the experience as well as self-assessing areas of strengths and areas in need for improvement to become an effective teacher” (La Paro et al., 2018, p. 372). While in our case, the final assignment for the course was individual in nature, we would encourage instructors to explore collective reflection techniques, which have been shown to provide more opportunities for higher level thinking than individual reflection for pre-service early childhood educators (Foong et al., 2018). For international students studying in Canada where the climate and natural landscapes differ from their home countries, a reflective and experiential approach to outdoor education was vital.

Third, ongoing communication about the learning format is important for any learning that takes place in a non-traditional setting, as students may need extra guidance. With our class format switching half-way through and with the outdoor days, it was imperative that we reassure students. Here, we draw a parallel between preparing students to suddenly learn online and preparing students to learn outside. As Kim (2020) noted, “good communication was the key to better online teaching” (p. 151) and we believe that similarly, good communication is key to better outdoor teaching, especially with students who are less familiar with local climate and weather (e.g., snow or heat). In the second part of the course, students had a chance to discuss how to prepare for the outdoor days during the online seminar, which was the day before. As such, Elizabeth and the students would check the weather together and review what to wear and bring to be comfortable outside for a few hours. This helped alleviate student anxiety and develop a sense of community.

At the outset of this study, we first asked: How do early childhood education students experience a practicum course focused on nature-based learning and outdoor play?

We also inquired: In what ways did the course structure, materials, readings, and setting promote meaningful learning of outdoor pedagogy? In response to these questions, we found notable answers. Students responded positively to this new practicum course and their reflections deepened once they were able to engage together in person in outdoor settings. The learning materials from the course became more meaningful when students met weekly in outdoor settings where theory came alive through action and discussion. Experiential learning allowed students to embody the knowledge gained.

Study limitations

Our study presents several limitations. One of them is a potential difference in the researcher’s approach to highlighting the significant statements, given the difference in number of statements found by each person. Given that our analysis process was not a systematic approach with a shared code book, but rather a more intuitive approach, we feel this was the result of researchers having a different lens and coming from a different perspective, which enriches the overall process and provided us with a starting point at which to start discussing our findings.

Next, due to the nature of the data collected, we as researchers realize that the college students may have written what they believed the instructors would want to hear; however, the overall impression we gained from analyzing the data provides us with insightful and meaningful reflections nonetheless. We also coupled the data from assignments with our observations and reflections of the class experience and found that they corroborated our themes. Last, we acknowledge, that there was a potential overlap between the 10 themes provided for the final assignment and the research finding themes, however, most of the themes for the assignment were broad and did not speak to particular content or experiences (e.g., “seminar discussions and learning activities,” “personal goals,” “personal top learning moments”). Two of our finding themes do somewhat overlap with the assignment themes (Deepening a personal connection to nature and the Land and Group discussions and building relationships), thus further exploration may be needed to nuance these findings.

Conclusion

Nature pedagogy and outdoor learning are at the forefront in the field of early childhood education in North America and beyond. As instructors, we were motivated to document our practices and to examine student experiences of a newly developed practicum course focused on outdoor pedagogy. Our research revealed several important aspects of the course that seemed meaningful to the students: (1) Embracing and preparing for the weather; (2) Learning from and with children; (3) Deepening a personal connection to nature and the Land; (4) Group discussions and building relationships; (5) Diversity of perspectives; (6) Increased understanding of the educator’s role. All these aspects together created a learning experience which was holistic, experiential, and diverse.

One of our primary reflections on this study – and this is case-specific but may nevertheless help inform other practice and research settings – relates to the particular uniqueness of teaching an outdoor course to a primarily non-Canadian group of college students. We suggest that in the case of students who may be less accustomed to the weather and climate of the teaching settings (e.g., international students) or who may not have personal values that align with the outdoor pedagogy model, it is imperative to offer embodied, lived experiences of nature and the outdoors as well as space to reflection on these experiences. Another of our closing reflections pertains to the challenge of assigning college students to appropriate sites for their practicum. Nature-based sites are still not the norm, therefore in our case it was not always possible to find suitable mentors and sites that would demonstrate the theory we wanted the students to learn. Here, we suggest that potentially shortening these placements to even out the student experiences and offering times to unpack their various placements through the course may be useful.

Finally, we suggest that further research could be conducted to enhance understanding of how students may be including outdoor pedagogy in their practice after graduation, as well as how the learning experience may differ based on seasons, instructor or simply in a context that is not affected by COVID-19. This outdoor practicum course continues to be successfully delivered with seminar classes occurring in person, in outdoor spaces and places. Students join a wider variety of practicum sites and remain in these sites for the duration of the practicum course (15 weeks). We encourage other post-secondary instructors to document and share their teaching practices so that outdoor teaching and learning can be improved for early childhood education students.

References

Adamson, G. S., Rouse, E., & Emmett, S. (2020). Recalling childhood: Transformative learning about the value of play through active participation. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 42(4), 362–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2020.1754309

Anderson, D., Comay, J., & Chiarotto, L. (2017). Natural curiosity: A resource for educators. The importance of indigenous perspectives in children’s environmental inquiry (2nd ed.). The laboratory school at the Dr. Eric Jackman institute of child study.

Bastien, B. (2004). Blackfoot ways of knowing: The worldview of the Siksikaitsitapi. University of Calgary Press. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/49840

Boileau, E., Dabaja, Z., & Harwood, D. (2021). Canadian nature-based early childhood education and the UN 2030 agenda for sustainable development: A partial alignment. International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education, 9(1), 77–93. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1324159.pdf

Bulk, Y. L., & Collins, B. (2023). Blurry lines: Reflections on insider research. Qualitative Inquiry, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778004231188048

Calderon, D. (2014). Speaking back to manifest destinies: A land education-based approach to critical curriculum inquiry. Environmental Education Research, 20(1), 24–36.

Campigotto, R., & Barrett, S. E. (2017). Creating space for teacher activism in environmental education: Pre-service teachers’ experiences. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 22, 42–57. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/article/view/1457

Chawla, L. (2015). Benefits of nature contact for children. Journal of Planning Literature, 30(4), 433–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412215595441

Clarke, A. (2023). Slow knowledge and the unhurried child. Routledge.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, A., Malone, K., & Barratt Hacking, E. (Eds.). (2018). Research handbook on childhoodnature. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51949-4_60-2

Deschamps, A., Scrutton, R., & Ayotte-Beaudet, J. P. (2022). School-based outdoor education and teacher subjective well-being: An exploratory study. Frontiers in Education, 7, 961054. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.961054

Dietze, B., & Kashin, D. (2016). Nature ideas: Explore, discover, connect

Dietze, B., & Kashin, D. (2019). Outdoor and nature play in early childhood education. Pearson Canada.

Dietze, B., & Kashin, D. (2024). Playing and learning in early childhood education. Pearson Canada.

Doreleyers, A., & Knighton, T. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic: Academic impacts on postsecondary students in Canada. Statistics Canada. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2020/statcan/45-28/CS45-28-1-2020-16-eng.pdf

Dumont, H., Istance, D., & Benavides, F. (Eds.). (2012). The nature of learning, using research to inspire practice. OECD Publications.

Foong, L., Binti, M., & Nolan, A. (2018). Individual and collective reflection: Deepening early childhood pre-service teachers’ reflective thinking during practicum. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 43(1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.23965/AJEC.43.1.05

George, C. T. (2019). Decolonize, then Indigenize: Critical insights on decolonizing education and indigenous resurgence in Canada. Antistatis, 9(1), 73–95.

Gray, S., & Colucci-Gray, L. (2018). Laying down a path in walking: Student teacher’s emerging ecological identities. Environmental Education Research, 25(3), 341–364.

Hamaidi, D., Al-Shara, I., Arouri, Y., & Awwad, F. A. (2014). Student-teacher’s perspectives of practicum practices and challenges. European Scientific Journal, 10(13), 191–214.

Harwood, D., Whitty, P., Green, C., & Elliot, E. (2020). Unsettling settlers’ ideas of land and relearning land with indigenous ways of knowing in ECEfS. In S. Elliott, E. Ärlemalm-Hagsér, & J. M. Davis (Eds.), Researching early childhood education for sustainability: Challenging assumptions and orthodoxies (pp. 25–37). Routledge.

Kim, J. (2020). Learning and teaching online during Covid-19: Experiences of student teachers in an early childhood education practicum. International Journal of Early Childhood, 52, 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-020-00272-6

Kimmerer, R. W. (2013). Braiding sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants. Milkweed Editions.

La Paro, K. M., Van Schagen, A., King, E., & Lippard, C. (2018). A systems perspective on practicum experiences in early childhood teacher education: Focus on interprofessional relationships. Early Childhood Education Journal, 46(4), 365–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-017-0872-8

Leather, M., Harper, N., & Obee, P. (2021). Pedagogy of play: Reasons to be playful in postsecondary education. Journal of Experiential Education, 44(3), 208–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053825920959684

Lees, A., Laman, T., T., & Calderón, D. (2021). Why didn’t I know this? Land education as an antidote to settler colonialism in early childhood teacher education. Theory into Practice, 60(3), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2021.1911482

Linn, V., & Jacobs, G. (2015). Inquiry-based field experiences: Transforming early childhood teacher candidates’ effectiveness. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 36(4), 272–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2015.1100143

Loebach, J., & Cox, A. (2020). Tool for observing play outdoors (TOPO): A new typology for capturing children’s play behaviours in outdoor environments. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 5611. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155611

MacEachren. (2018). First nation pedagogical emphasis on imitation and making the stuff of life: Canadian lessons for indigenizing forest schools. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 21(1), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-017-0003-4

Makovichuk, L., Hewes, J., Lirette, P., & Thomas, N. (2014). Flight: Alberta’s early learning and care framework. https://flightframework.ca/

Merrick, C. (Ed.). (2019). Nature-based preschool professional practice guidebook: Teaching, environments, safety, administration. North American Association for Environmental Education.

Nazir, J. (2016). Using phenomenology to conduct environmental education research: Experience and issues. The Journal of Environmental Education, 47(3), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2015.1063473

North American Association for Environmental Education (2023). Nature preschools in the United States: 2022 national survey. https://naturalstart.org/nature-preschools-united-states-2022-survey

Nowrouzi-Kia, B., Osipenko, L., Eftekhar, P., Othman, N., Alotaibi, S., Schuster, A. M., Suh, H. S., & Duncan, A. (2022). The early impact of the global lockdown on post-secondary students and staff: A global, descriptive study. SAGE Open Medicine, 10, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/20503121221074480

Nxumalo, F. (2019). Decolonizing place in early childhood education. Routledge.

Pacini-Ketchabaw, V., Taylor, A., & Blaise, M. (2016). Decentring the human in multispecies ethnographies. In C. A. Taylor & C. Hughes (Eds.), Posthuman research practices in education (pp. 149–167). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137453082

Payne, P. G., & Wattchow, B. (2009). Phenomenological deconstruction, slow pedagogy, and the corporeal turn in wild environmental/outdoor education. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 14. https://cjee.lakeheadu.ca/issue/view/50

Pitsikali, A., & Parnell, R. (2020). Fences of childhood: Challenging the meaning of playground boundaries in design. Frontiers of Architectural Research, 9, 656–669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foar.2020.03.001

Queen’s University. (2023). Elders, knowledge keepers, and cultural advisors. Office of Indigenous initiatives. https://www.queensu.ca/indigenous/ways-knowing/elders-knowledge-keepers-and-cultural-advisors

Rooney, T. (2018). Weather worlding: Learning with the elements in early childhood. Environmental Education Research, 24(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1217398

Smith, C. D. (2020). Creating ethical spaces: Opportunities to connect with the land for life and learning in the NWT. The Gordon Foundation. https://gordonfoundation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Chloe_Dragon_Smith_JGNF_2018-2019.pdf Jane Glassco Northern Fellowship.

Stolz, S. A. (2020). Phenomenology and phenomenography in educational research: A critique. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 52(10), 1077–1096. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1724088

Telford, J. (2020). Phenomenological approaches to research in outdoor studies. In B. Humberstone, & H. Prince (Eds.), Research methods in outdoor studies (pp. 47–56). Routledge.

Tremblay, M., Gray, C., Babcock, S., Barnes, J., Bradstreet, C., Carr, D., Chabot, G., Choquette, L., Chorney, D., Collyer, C., Herrington, S., Janson, K., Janssen, I., Larouche, R., Pickett, W., Power, M., Sandseter, E., Simon, B., & Brussoni, M. (2015). Position statement on active outdoor play. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 12(6), 6475–6505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph120606475

van Groll, N., & Kummen, K. (2021). Troubled pedagogies and COVID-19: Fermenting new relationships and practices in early childhood care and education. Journal of Childhood Studies, 46(3), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.18357/jcs463202120047

Webb, A., & Welsh, A. J. (2019). Phenomenology as a methodology for scholarship of teaching and learning research. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 7(1), 168–181. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.7.1.11

Wishart, L., & Rouse, E. (2019). Pedagogies of outdoor spaces: An early childhood educator professional learning journey. Early Child Development and Care, 189(14), 2284–2298. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1450250

Wolf, C., Kunz, P., & Robin, N. (2022). Emerging themes of research into outdoor teaching in initial formal teacher training from early childhood to secondary education - A literature review. The Journal of Environmental Education, 53(4), 199–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2022.2090889

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose. The study was approved by the Bow Valley College Research Ethics Board.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Boileau, E., O’Donoghue, L. Learning to embrace outdoor pedagogy: early childhood education student experiences of a nature-focused practicum. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-023-00153-1

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42322-023-00153-1